Mind the Gap: A Solution to the Robustness Problem of Turing Patterns Through Patterning Mode Isolation

Abstract

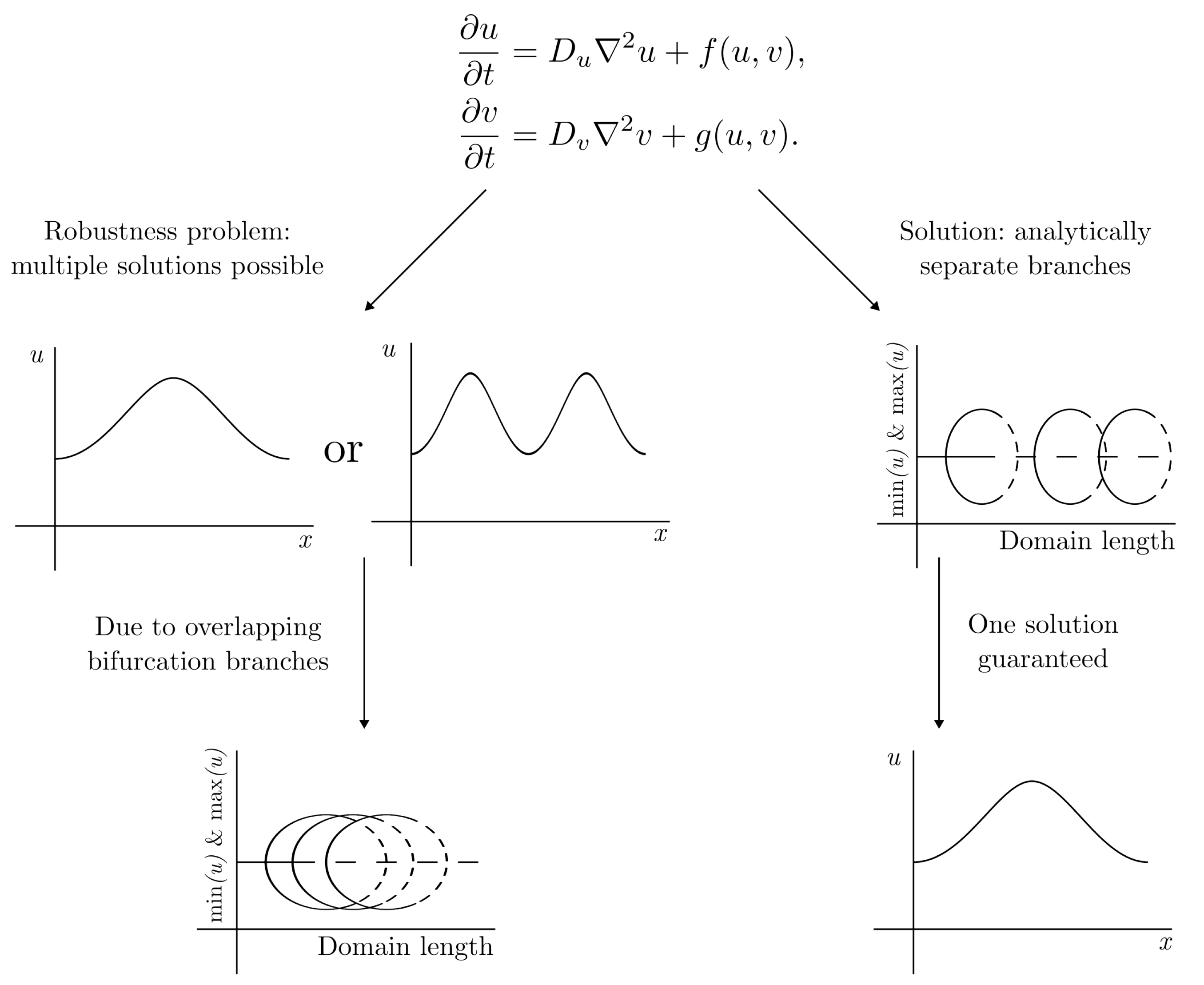

1. Introduction

2. Framework

Domain Growth

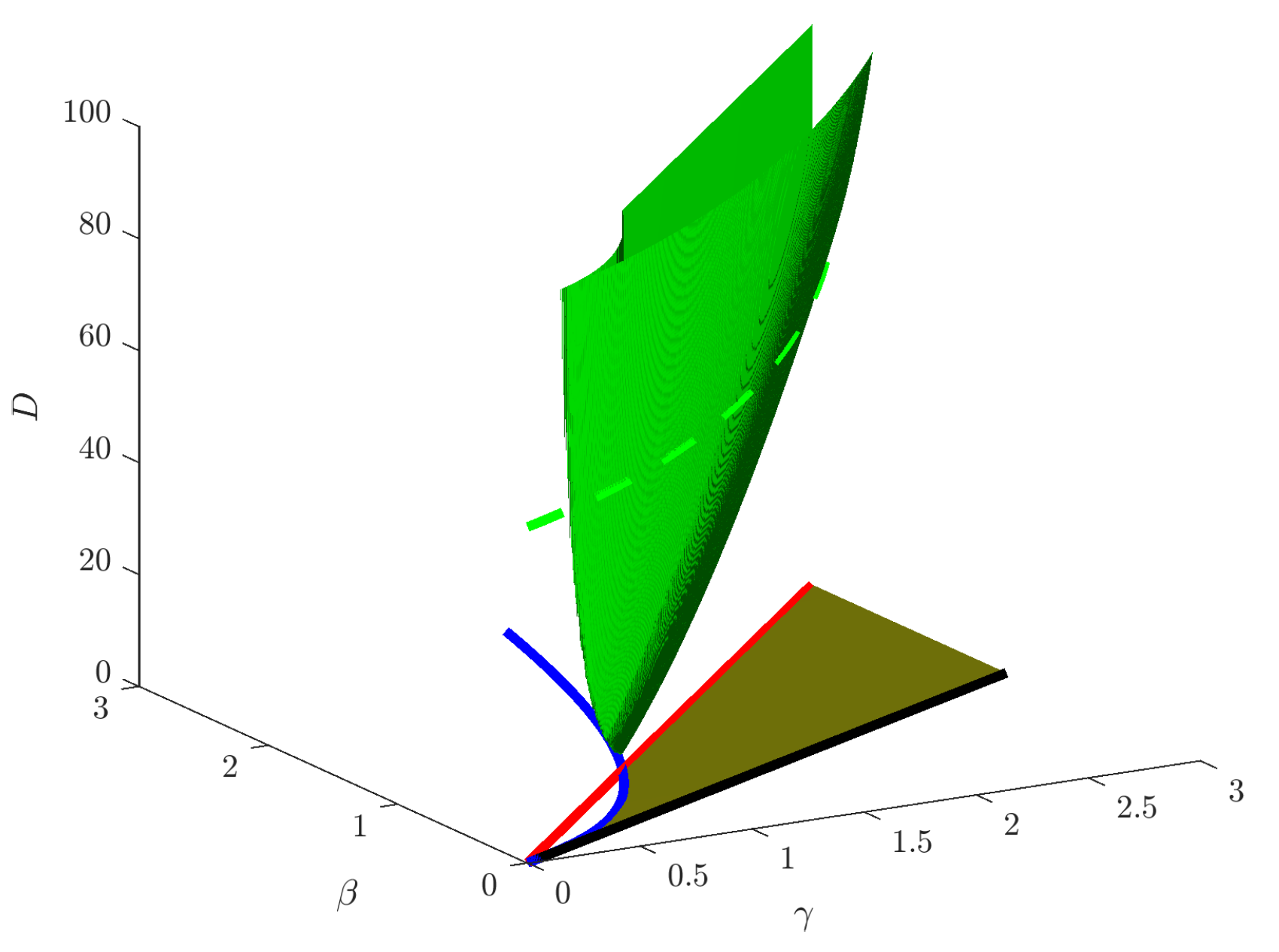

3. Turing Conditions

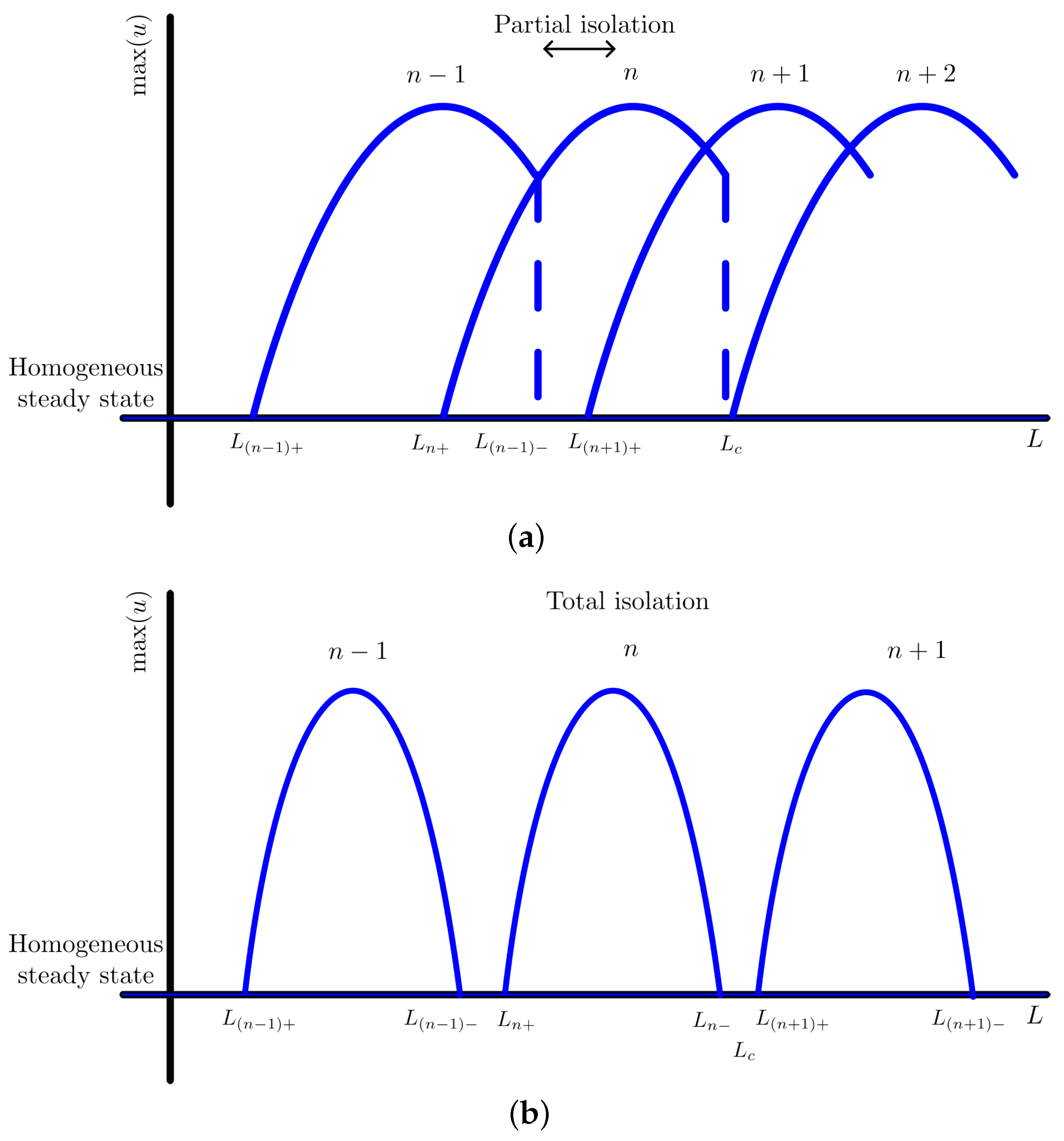

4. Mode Isolation

5. Simulation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turing, A.M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1952, 237, 37–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, T.E.; Baker, R.E.; Maini, P.K. Chapter 35: Turing’s theory of morphogenesis. In The Turing Guide; Sprevak, M., Copeland, J., Bowen, J.W.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, A.L.; Gaffney, E.A.; Maini, P.K.; Klika, V. Modern perspectives on near-equilibrium analysis of Turing systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2021, 379, 20200268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.D. Mathematical Biology II: Spatial Models and Biomedical Applications, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, T.E. Chapter 48: Mighty Morphogenesis. In 50 Visions of Mathematics; Parc, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Kepper, P.; Castets, V.; Dulos, E.; Boissonade, J. Turing-type chemical patterns in the chlorite-iodide-malonic acid reaction. Physica D 1991, 49, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, F.; Mercker, M.; Richter, T.; Marciniak-Czochra, A. Post-Turing tissue pattern formation: Advent of mechanochemistry. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, P. Forging patterns and making waves from biology to geology: A commentary on Turing (1952) ‘The chemical basis of morphogenesis’. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, R.; Marcon, L.; Bastida, M.F.; Junco, M.; Quintana, L.; Dahn, R.; Kmita, M.; Sharpe, J.; Ros, M.A. Hox genes regulate digit patterning by controlling the wavelength of a Turing-type mechanism. Science 2012, 338, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, I.; Harn, C.; Wang, S.P.; Lai, Y.C.; Van Handel, B.; Liang, Y.C.; Tsai, S.; Schiessl, I.M.; Sarkar, A.; Xi, H.; et al. Symmetry breaking of tissue mechanics in wound induced hair follicle regeneration of laboratory and spiny mice. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Montgomery, S.M.; Yue, L.; Wei, Y.; Song, Y.; Nomura, T.; Qi, H.J. Turing pattern–based design and fabrication of inflatable shape-morphing structures. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, A.S.; Coppens, M.O. Re-designing materials for biomedical applications: From biomimicry to nature-inspired chemical engineering. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2019, 377, 20180268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Z.; Li, J.; You, P.; Han, L.; Qiu, M.; Chen, G.; He, Y.; Liang, S.; Xiang, B.; Su, Y.; et al. Turing patterns with high-resolution formed without chemical reaction in thin-film solution of organic semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, A.L.; Burton, A.M.; Fadai, N.T.; Van Gorder, R.A. Emergent structures in reaction-advection-diffusion systems on a sphere. Phys. Rev. E 2018, 97, 042215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.L.; Klika, V.; Maini, P.K.; Headon, D.; Gaffney, E.A. Isolating Patterns in Open Reaction–Diffusion Systems. Bull. Math. Biol. 2021, 83, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, T.E. Pattern production through a chiral chasing mechanism. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 032401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maini, P.K.; Woolley, T.E.; Baker, R.E.; Gaffney, E.A.; Lee, S.S. Turing’s model for biological pattern formation and the robustness problem. Interface Focus 2012, 2, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.C.; Woolley, T.E.; Jiang, T.X.; Wu, P.; Maini, P.K.; Widelitz, R.; Chuong, C.M. Inhibition of gap junctions stimulates Turing-type periodic feather pattern formation during chick skin development. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, S. How animals get their skin patterns: Fish pigment pattern as a live Turing wave. In Systems Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, J.D.; Sudderick, Z.R.; Shih, B.B.; Batho-Samblas, C.; Charlton, L.; Krause, A.L.; Anderson, C.; Riddell, J.; Balic, A.; Li, J.; et al. The developmental basis of fingerprint pattern formation and variation. Cell 2023, 186, 940–956.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.W.; Kwak, S.; Woolley, T.E.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, E.J.; Baker, R.E.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, J.S.; Tickle, C.; Maini, P.K.; et al. Interactions between Shh, Sostdc1 and Wnt signaling and a new feedback loop for spatial patterning of the teeth. Development 2011, 138, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.K.W.; Freem, L.; Zhao, D.; Painter, K.J.; Woolley, T.E.; Gaffney, E.A.; McGrew, M.J.; Tzika, A.; Milinkovitch, M.C.; Schneider, P.; et al. Feather arrays are patterned by interacting signalling and cell density waves. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crampin, E.J. Reaction-Diffusion Patterns on Growing Domains. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crampin, E.J.; Maini, P.K. Modelling biological pattern formation: The role of domain growth. Commun. Theory Biol. 2001, 6, 229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Madzvamuse, A.; Maini, P.K. Velocity-induced numerical solutions of reaction-diffusion systems on continuously growing domains. J. Comput. Phys. 2007, 225, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzvamuse, A.; Wathen, A.J.; Maini, P.K. A moving grid finite element method applied to a model biological pattern generator. J. Comp. Phys. 2003, 190, 478–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.A.; Matthews, P.C.; Byrne, H.M. Interactions between pattern formation and domain growth. Bull. Math. Biol. 2006, 68, 1975–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klika, V.; Kozák, M.; Gaffney, E.A. Domain Size Driven Instability: Self-Organization in Systems with Advection. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2018, 78, 2298–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, T.E.; Baker, R.E.; Gaffney, E.A.; Maini, P.K. Stochastic reaction and diffusion on growing domains: Understanding the breakdown of robust pattern formation. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 046216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, T.E.; Baker, R.E.; Gaffney, E.A.; Maini, P.K. Influence of stochastic domain growth on pattern nucleation for diffusive systems with internal noise. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 041905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, L.J.; Woolley, T.E.; Baker, R.E. Noise-induced temporal dynamics in Turing systems. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87, 042719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnakenberg, J. Simple chemical reaction systems with limit cycle behaviour. J. Theor. Biol. 1979, 81, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppänen, T.; Karttunen, M.; Kaski, K.; Barrio, R.A.; Zhang, L. A new dimension to Turing patterns. Physica D 2002, 168, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, T.; Karttunen, M.; Barrio, R.; Kaski, K. Morphological transitions and bistability in Turing systems. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 70, 066202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzini, B.; Gambino, G.; Lacitignola, D.; Lupo, S.; Sammartino, M.; Sgura, I. Weakly nonlinear analysis of Turing patterns in a morphochemical model for metal growth. Comput. Math. Appl. 2015, 70, 1948–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crampin, E.J.; Maini, P.K. Reaction-diffusion models for biological pattern formation. Methods Appl. Anal. 2001, 8, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crampin, E.J.; Gaffney, E.A.; Maini, P.K. Reaction and diffusion on growing domains: Scenarios for robust pattern formation. Bull. Math. Biol. 1999, 61, 1093–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crampin, E.J.; Gaffney, E.A.; Maini, P.K. Mode-doubling and tripling in reaction-diffusion patterns on growing domains: A piecewise linear model. J. Math. Biol. 2002, 44, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crampin, E.J.; Hackborn, W.W.; Maini, P.K. Pattern formation in reaction-diffusion models with nonuniform domain growth. Bull. Math. Biol. 2002, 64, 747–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uecker, H.; Wetzel, D.; Rademacher, J.D.M. pde2path—A Matlab package for continuation and bifurcation in 2D elliptic systems. Numer. Math. Theory Methods Appl. 2014, 7, 58–106. [Google Scholar]

- Uecker, H. Numerical Continuation and Bifurcation in Nonlinear PDEs; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dohnal, T.; Rademacher, J.D.M.; Uecker, H.; Wetzel, D. pde2path 2.0: Multi-parameter continuation and periodic domains. In Proceedings of the 8th European Nonlinear Dynamics Conference, Vienna, Austria, 6–11 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barrass, I.; Crampin, E.J.; Maini, P.K. Mode transitions in a model reaction-diffusion system driven by domain growth and noise. Bull. Math. Biol. 2006, 68, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.L.; Klika, V.; Woolley, T.E.; Gaffney, E.A. From one pattern into another: Analysis of Turing patterns in heterogeneous domains via WKBJ. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20190621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gorder, R.A.; Klika, V.; Krause, A.L. Turing conditions for pattern forming systems on evolving manifolds. J. Math. Biol. 2021, 82, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreyszig, E. Advanced Engineering Mathematics, 8th ed.; Wiley: New Delhi, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, M.J.; Wei, J. The existence and stability of asymmetric spike patterns for the Schnakenberg model. Stud. Appl. Math. 2002, 109, 229–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollkind, D.J.; Manoranjan, V.S.; Zhang, L. Weakly nonlinear stability analyses of prototype reaction-diffusion model equations. SIAM Rev. 1994, 36, 176–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnost, J.J.; Desoer, C.A. An elementary proof of the Routh-Hurwitz stability criterion. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 1991, 10, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, T.E.; Baker, R.E.; Tickle, C.; Maini, P.K.; Towers, M. Mathematical modelling of digit specification by a sonic hedgehog gradient. Dev. Dyn. 2014, 243, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlie, R.C. Fine tuning of blood glucose concentrations. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1985, 10, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, V.; Luna, E.; Ton, J.; Cerezo, M.; García-Agustín, P.; Flors, V. Fine tuning of reactive oxygen species homeostasis regulates primed immune responses in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breward, C.J.W.; Byrne, H.M.; Lewis, C.E. Modelling the interactions between tumour cells and a blood vessel in a microenvironment within a vascular tumour. Eur. J. Appl. Math. 2001, 12, 529–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegg, J.A.; Menon, S.N.; Byrne, H.M.; McElwain, D.L.S. A current perspective on wound healing and tumour-induced angiogenesis. Bull. Math. Biol. 2020, 82, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Woolley, T.E. Mind the Gap: A Solution to the Robustness Problem of Turing Patterns Through Patterning Mode Isolation. AppliedMath 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010003

Woolley TE. Mind the Gap: A Solution to the Robustness Problem of Turing Patterns Through Patterning Mode Isolation. AppliedMath. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleWoolley, Thomas E. 2026. "Mind the Gap: A Solution to the Robustness Problem of Turing Patterns Through Patterning Mode Isolation" AppliedMath 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010003

APA StyleWoolley, T. E. (2026). Mind the Gap: A Solution to the Robustness Problem of Turing Patterns Through Patterning Mode Isolation. AppliedMath, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010003