1. Introduction

Forest fires constitute a critical environmental hazard, posing severe threats to global ecosystems and biodiversity. A comprehensive understanding of their spatiotemporal dynamics, coupled with the development of robust predictive models, is indispensable for effective disaster prevention and ecological conservation. Extensive research has been conducted in recent years to analyze the spatial clustering behavior and temporal evolution of forest fires. Kirana et al. [

1] applied spatial metrics including Voronoï polygon area, Morishita index, and fractal dimension to characterize the clustering patterns of fire incidents in Tuscany, Italy, from 1997 to 2003, revealing notable variations across temporal scales. Lee [

2] employed global and local Moran’s I indices to establish a significant correlation between the spatial aggregation of fires and the efficiency of firefighting resource allocation, underscoring the value of spatial autocorrelation analysis in identifying high-risk zones. Similarly, Li et al. [

3] systematically investigated spatiotemporal clustering in lightning-induced fires using statistical methods, kernel density estimation, and spatial autocorrelation models, further validating the efficacy of these techniques in risk assessment and prediction. Kim et al. [

4] demonstrated how integrating building information modeling with visualization techniques can enhance the management process of fire disasters, highlighting the value of spatially explicit decision support systems in emergency response. In the domain of optimization under uncertainty, Jiang and Ji [

5] proposed a smart predict-then-optimize framework for locating hurricane shelters, illustrating the effectiveness of coupling machine learning predictions with operational decision-making, an approach that informs the risk-based zoning and resource allocation perspective adopted in this study. Ku and Liu [

6] applied deep neural networks to model fire incidence, showcasing the capability of advanced computational methods in capturing complex nonlinear patterns of fire occurrence. These studies collectively affirm that investigating spatiotemporal patterns and advancing predictive methodologies are essential for formulating targeted and scientifically-grounded fire management strategies. Nonetheless, research specifically addressing fire occurrence patterns and predictive modeling in Guangdong Province remains scarce, presenting a research gap that this study intends to fill.

The growing demand for accurate forest fire prediction has propelled machine learning into prominence as a powerful computational tool. Its capability to model complex spatial relationships and automatically extract high-level features from multi-source environmental data makes it particularly well-suited for forecasting fire events. As data availability and computational power increase, machine learning approaches, especially ensemble methods, have undergone rapid development. Among these, the XGBoost algorithm (Extreme Gradient Boosting), introduced by Chen and Guestrin [

7], has gained widespread adoption due to its efficient handling of structured data and strong predictive performance. By integrating decision trees with gradient boosting frameworks and employing second-order Taylor expansion and parallel processing, XGBoost achieves enhanced training efficiency and model accuracy, even with sparse or incomplete datasets. Subsequent applications, such as the hybrid model developed by Mata et al. [

8], have incorporated meteorological, topographic, and vegetation variables with XGBoost to improve fire risk prediction. Khanmohammadi et al. [

9] demonstrated its utility in predicting fire spread using historical ignition data and weather conditions, and Umamaheswari et al. [

10] used CNN-RF and CNN-XGboost machine learning algorithms. Despite these advances, many models overlook the integration of comprehensive multi-dimensional drivers, thereby limiting generalizability in complex real-world settings [

11]. Moreover, the sensitivity of XGBoost to hyperparameters, including learning rate, tree depth, and subsampling ratio, poses tuning challenges that are poorly addressed by conventional methods [

12]. To overcome these limitations, metaheuristic optimization algorithms such as simulated annealing [

13], particle swarm optimization [

14], grey wolf optimization [

15], and the sparrow search algorithm (SSA) [

16] have been introduced for automated parameter calibration. SSA, in particular, exhibits superior global search capability, convergence speed, and adaptability, making it highly effective for improving model performance and solution quality.

In light of the above, this study proposes an enhanced forest fire prediction framework for Guangdong Province based on SSA-optimized XGBoost modeling. We integrate a multifaceted set of predictors spanning meteorological, topographic, vegetation, socioeconomic, and human activity dimensions to capture the predominant drivers of fire incidence. The application of kernel density estimation [

11] and spatial autocorrelation techniques facilitates a detailed analysis of spatiotemporal fire patterns, thereby informing risk zoning and preventive strategies. By synergistically combining factor analysis and optimized machine learning, this approach not only improves predictive accuracy and mitigates overfitting but also provides actionable insights for fire management in Guangdong. Ultimately, this research contributes to regional ecological security and offers a transferable methodology for forest fire prediction in other geographically comparable regions.

2. Study Area Characterization

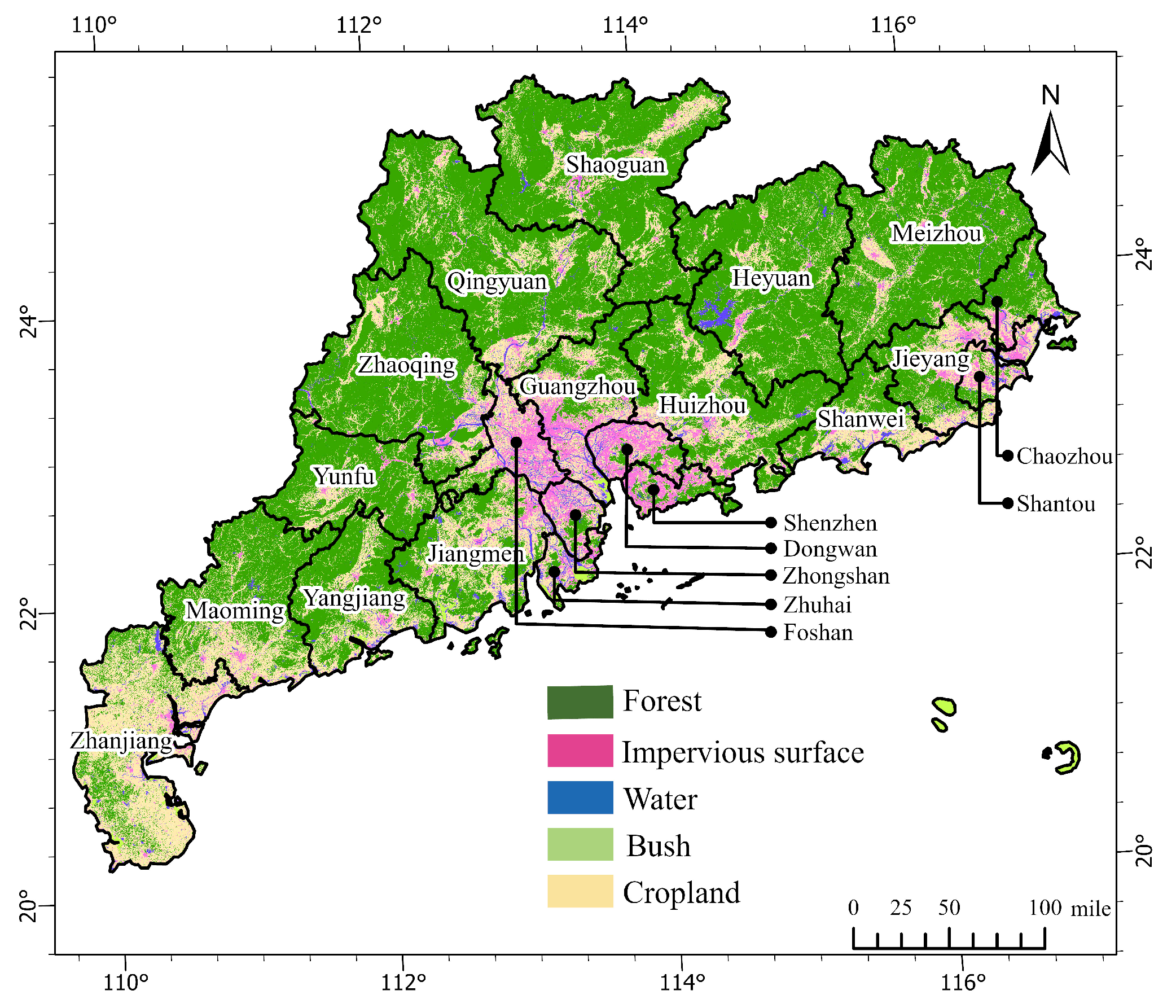

Guangdong Province (

–

N,

–

E) is situated at the southernmost part of mainland China. It is bordered by Jiangxi and Hunan to the north, Fujian to the northeast, and Guangxi to the west, with its southern coast facing the South China Sea. Covering an area of 179,700 km

2 (see

Figure 1), the province exhibits significant topographical diversity: the northern region is predominantly mountainous, with the Nanling Range containing Guangdong’s highest peak, Mount Shikengkong (1902 m) in Ruyuan County, while the southern areas are characterized by extensive coastal plains. The Pearl River Delta represents a typical low-lying area, with elevations near sea level at the estuary-resulting in a maximum elevation difference of over 1900 m.

Climatically, Guangdong experiences a subtropical to tropical monsoon climate, characterized by high temperatures, abundant rainfall, long summers, and virtually nonexistent winters. Distinct dry and wet seasons are driven by monsoon circulation. The complex topography combined with a lengthy coastline contributes to pronounced vertical climatic zonation and regional microclimates.

As a key forest region in southern China, Guangdong is covered by dense subtropical evergreen broadleaved forests. The accumulation of surface combustible materials following typhoons, combined with autumn and winter dryness, leads to persistently high fire risks. Recent increases in global extreme weather events have further intensified wildfire threats, particularly in mountainous areas, adding pressure to forest management efforts.

3. Data Sources and Preprocessing

Terrain data were obtained from the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM) product with a spatial resolution of 30 m, accessed via

http://www.gscloud.cn (accessed on 19 April 2018). Using ArcGIS Pro 3.0.1, we processed the digital elevation model (DEM) to generate layers representing elevation, slope gradient, and aspect. Meteorological variables, including annual mean temperature, monthly cumulative precipitation, and sunshine duration, were acquired from the National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center and the China Meteorological Data Service Center. Vegetation cover data were represented by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), sourced from the Resource and Environment Science Data Center (

http://www.resdc.cn) (accessed on 7 May 2020). Anthropogenic factors such as population density and Euclidean distances from ignition points to the nearest roads and waterways were processed in ArcGIS Pro based on 1:250,000-scale national geospatial databases provided by the National Geomatics Center of China, supplemented with records from the China Statistical Yearbook.

Forest fire data for Guangdong Province were derived from NASA’s MOD14A1 fire product (2014–2023), comprising 3693 images covering UTM Zone 49 and representing 92 annual observation scenes. The massive datasets were batch-processed using the MODIS Reprojection Tool (MRT), encompassing steps of data fusion, reprojection, and format conversion. Geographic information system (GIS) tools [

12] were employed to classify thermal anomalies into ten levels (0–9) across Guangdong, generating 204872 grid nodes via raster-to-point conversion. Each node was assigned a corresponding MODIS fire mask pixel value, from which high-confidence fire detections (levels 8–9) were extracted, yielding 3155 fire points (

Table 1). After screening based on forest distribution and eliminating duplicate records within a 5-km radius and 24-h window, 1571 forest fire points were retained, accounting for 0.076% of all nodes in the province.

Non-fire points were sampled via stratified random sampling from thermal anomalies below confidence level 8. The sampling strata proportions were aligned with the distribution of node counts across thermal anomaly levels: 16.7% for levels 0–3, 33.3% for levels 4–5, 33.3% for levels 6–7, and 16.7% for levels 8–9. This procedure generated 7845 non-fire points, which were combined with the forest fire points to construct the final dataset comprising 9416 samples.

It should be noted that this study utilized only high-confidence MODIS detections (levels 8–9), which entails inherent limitations under specific geographic and meteorological conditions, potentially introducing sampling bias. Specifically, fires occurring near water bodies or within forest–urban interface zones often generate numerous low-confidence detections that obscure high-confidence signatures. Similarly, thick cloud cover attenuates the sensor’s effective signal, resulting in predominantly low-confidence detections. Such potential fire points were excluded during data preprocessing due to failure to meet the confidence threshold, which may lead to omitted fire events in these regions and consequently exert unquantified impacts on model training and evaluation.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [

11] is a non-parametric statistical method used to analyze the distribution patterns of point-based geographical data. It is particularly suited to characterizing continuous spatial variations and distance-decay effects associated with discrete geographic events. This technique is widely employed to address positional uncertainties in forest fire ignition data and has been extensively applied in studies examining spatial distribution patterns of wildfires and delineating fire risk zones [

17]. The fundamental formula of KDE is given as follows [

11]:

where

n represents the total number of fire incident points;

h denotes the bandwidth, a smoothing parameter that controls the scale of density estimation;

K is the kernel function, which determines the shape of the distribution used for weighting; and

is the Euclidean distance from the point of estimation

to the observed fire incident location

x.

4.2. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

Spatial autocorrelation analysis evaluates the degree of correlation among similar attribute values across neighboring spatial units. This methodology is applied at both global and local scales, with Moran’s index being the most widely used statistic for revealing spatial distribution patterns of unit attributes [

18]. The formula for Moran’s index is given as follows [

19]:

where

denotes Moran’s index,

n signifies the total number of fire points,

represents the element of the spatial weight matrix between units

i and

j,

and

correspond to the kernel density values at regions

i and

j respectively, and

indicates the mean

x.

A standardized statistic

Z is used to assess the significance of spatial autocorrelation in the kernel density distribution. It is computed as:

where

denotes Moran’s index,

represents the expected value of Moran’s index

under the null hypothesis of no spatial autocorrelation, and

signifies the variance of Moran’s index

.

At a significance level of

, the critical value of the standard normal distribution is 1.96. The spatial autocorrelation pattern is interpreted as follows: if

, there is significant positive spatial autocorrelation; if

, significant negative spatial autocorrelation is present; If

, spatial autocorrelation is not significant, indicating a random distribution of kernel density values [

20].

4.3. XGBoost Prediction Model

4.3.1. Model Performance Optimization Strategy

Forest fire prediction necessitates the integration of multi-source heterogeneous data, encompassing meteorological factors (e.g., temperature, precipitation, sunshine duration), topographic features (elevation, slope gradient, aspect), vegetation attributes (such as NDVI), and anthropogenic influences (population density, distance to roads and waterways). The XGBoost model is well-suited to processing large-scale spatial datasets efficiently by leveraging parallel computing architecture and cache optimization mechanisms, which significantly enhance training speed. However, the model’s performance is highly sensitive to hyperparameter settings, including the number of weak learners, shrinkage weight, and maximum tree depth. Conventional tuning methods that rely on manual empirical searches are often time-consuming and susceptible to converging to local optima, thus constraining predictive accuracy. To address these challenges, this study introduces an integrated framework that optimizes XGBoost through the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA). This approach capitalizes on SSA’s strong global search capability and adaptive convergence properties to automate the identification of optimal parameter configurations. By reducing the subjectivity associated with manual tuning, the proposed strategy improves the model’s ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships, thereby substantially enhancing prediction accuracy and generalization performance in forest fire risk assessment [

17].

4.3.2. Model Evaluation Methods and Criteria

Four evaluation metrics were adopted to assess model performance: Overall Accuracy (

), Recall (

R), Precision (

P), and the

Score. These metrics are defined as follows [

12]:

where

denotes true positives,

signifies false positives,

represents true negatives, and

indicates false negatives. The

score represents the harmonic mean of precision

P and recall

R, providing a balanced measure that integrates both performance aspects.

5. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Forest Fires in Guangdong

5.1. Temporal Distribution Patterns

Analysis of the forest fire dataset in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023 identified a total of 1571 fire incidents, averaging 157 occurrences per year. The temporal distribution of fires was analyzed through annual and monthly aggregations, with the resulting interannual variations and monthly fluctuation patterns illustrated in

Figure 2.

Forest fire frequency in Guangdong exhibited a fluctuating downward trend from 2014 to 2023. Annual data show a continuous decrease from 2014 to 2020, followed by a brief rebound in 2021 before the decline resumed. The highest number of incidents occurred in 2014, with 193 cases accounting for 12.29% of the total recorded during this decade, while the lowest was observed in 2022, with 107 incidents representing 6.81%. Monthly distribution patterns reveal significant seasonality, with fire occurrences peaking from January to April and September to November. March recorded the highest proportion of fires at 16.32%. Notably, 79.78% of all fires took place within the official forest fire prevention period (October 1 to April 30 of the following year), highlighting the importance of reinforced regulatory measures during this interval.

5.2. Spatial Distribution Patterns

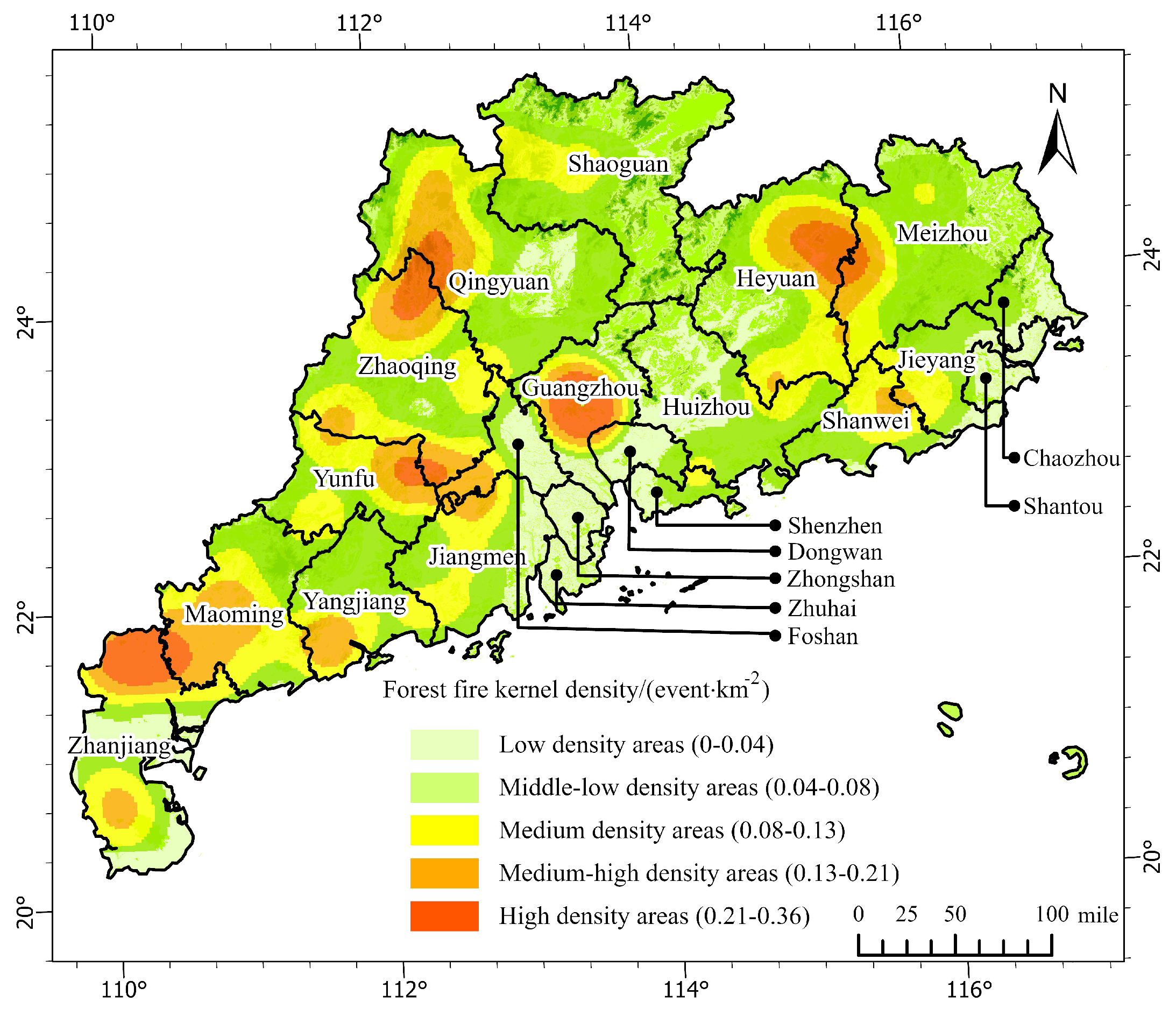

Utilizing ArcGIS Pro, this study applied kernel density analysis with an output cell size of 2176.3 m to generate smoothed spatial distribution maps of fire density, identifying core clustering zones of forest fires across Guangdong. The resulting density values were classified into five distinct risk tiers using the Jenks natural breaks method: low, medium-low, medium, medium-high, and high-density zones. As shown in

Figure 3, the spatial distribution of forest fires exhibits marked regional variation. Medium-high and high-density zones are predominantly concentrated in the southwestern and northern mountainous regions, with limited presence in central areas, together accounting for 15.71% of the province’s total area. In contrast, low and medium-low density zones are largely distributed across the eastern coastal plains, covering 62.49% of Guangdong. This spatial pattern correlates strongly with topographic characteristics, underscoring the inherent heterogeneity in regional fire risk.

Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of density classifications at the county level. Cities such as Guangzhou, Zhaoqing, Zhanjiang, Qingyuan, Maoming, Meizhou, and Heyuan contain the majority of medium-high density zones and include all five risk tiers. Core high-density areas are identified in Lianjiang County, Yangshan County, Huaiji County, Longchuan County, and the urban core of Guangzhou. In contrast, regions including Shaoguan, Huizhou, and Chaozhou are characterized predominantly by low-density patterns, with Shaoguan’s low-density areas making up 19.56% of its territory, the highest proportion among all prefectures. This spatial variation arises from a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors: frequent agricultural burning and arid conditions elevate fire risk in the southwest, while forest–agriculture interfaces increase ignition sources in northern mountains. Conversely, maritime humidity and extensive urban land cover mitigate fire likelihood along the eastern coast.

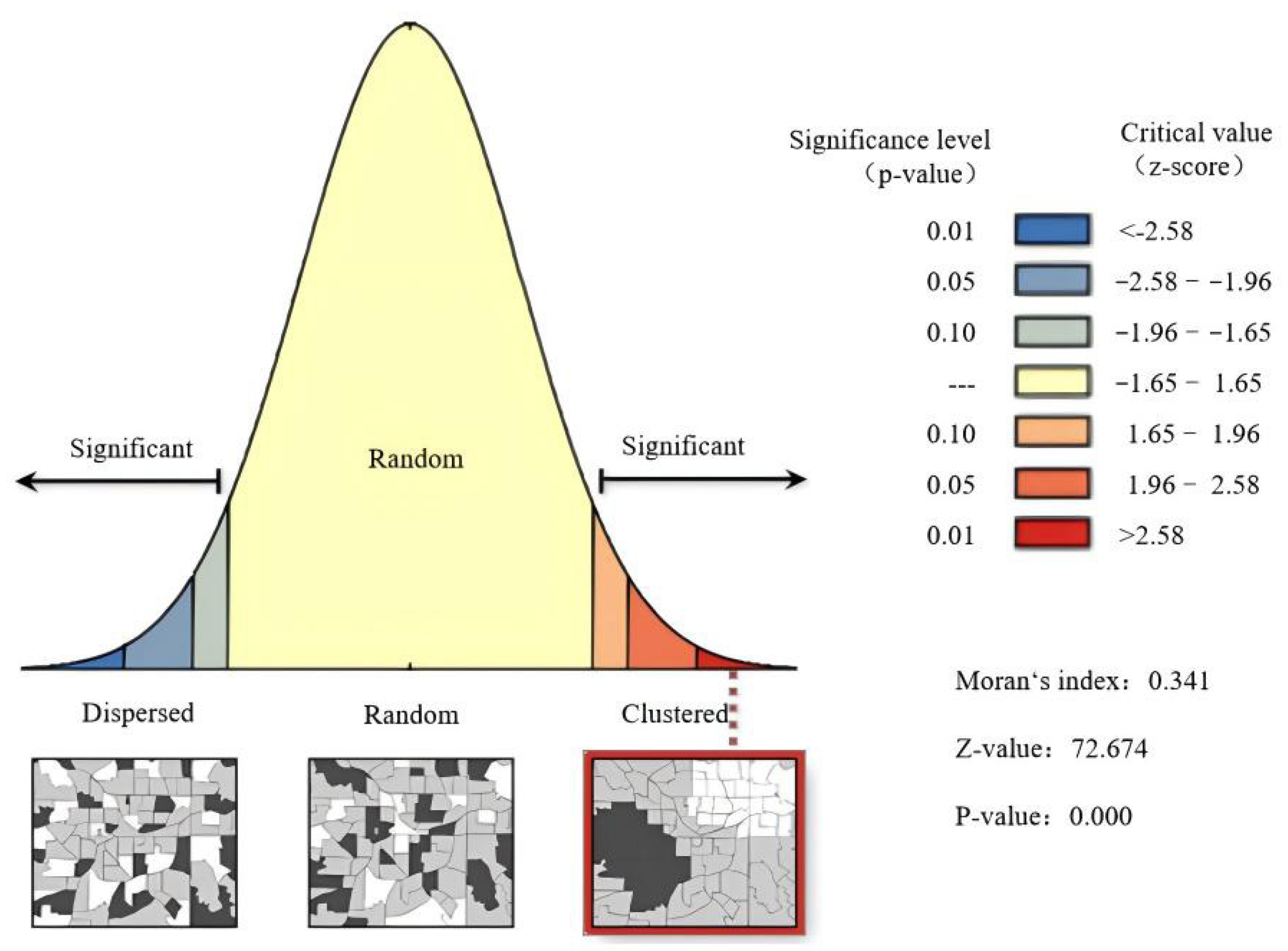

Given the inherent spatial heterogeneity of geographical influencing factors, quantitative approaches are essential for assessing interregional spatial dependencies [

20]. In this study, global spatial autocorrelation was measured using Moran’s I. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the analysis results show a Moran’s I value of 0.341, which is statistically significant (

,

), demonstrating a strongly positive spatial autocorrelation in forest fire density across Guangdong. This indicates that the distribution of forest fire risk exhibits clear spatial clustering patterns.

6. Guangdong Forest Fire XGBoost Prediction Model

6.1. Model Dataset Construction

In the development of the XGBoost prediction model, the forest fire dataset was designated as the response variable for model construction [

21]. Discrete raster layers representing forest fire drivers were encoded using ArcGIS Pro. Both continuous and discrete raster data pertaining to fire-driving factors were converted into point features to serve as predictor variables. The resulting point datasets, comprising 10 predictor variables and one response variable, were spatially joined to form an integrated modeling dataset. Following data extraction, min-max normalization was applied to standardize the input features, and records containing missing or invalid values were removed to yield the final analytical dataset.

To mitigate the potential influence of random sampling variability on variable selection, the complete dataset was randomly partitioned into a modeling subset (80%) and an independent test subset (20%). The modeling subset was further subjected to five repeated random splits into training (75%) and validation (25%) subsets, thereby generating five intermediate sample sets for robust internal evaluation. A partial visualization of the forest fire data is presented in

Figure 5.

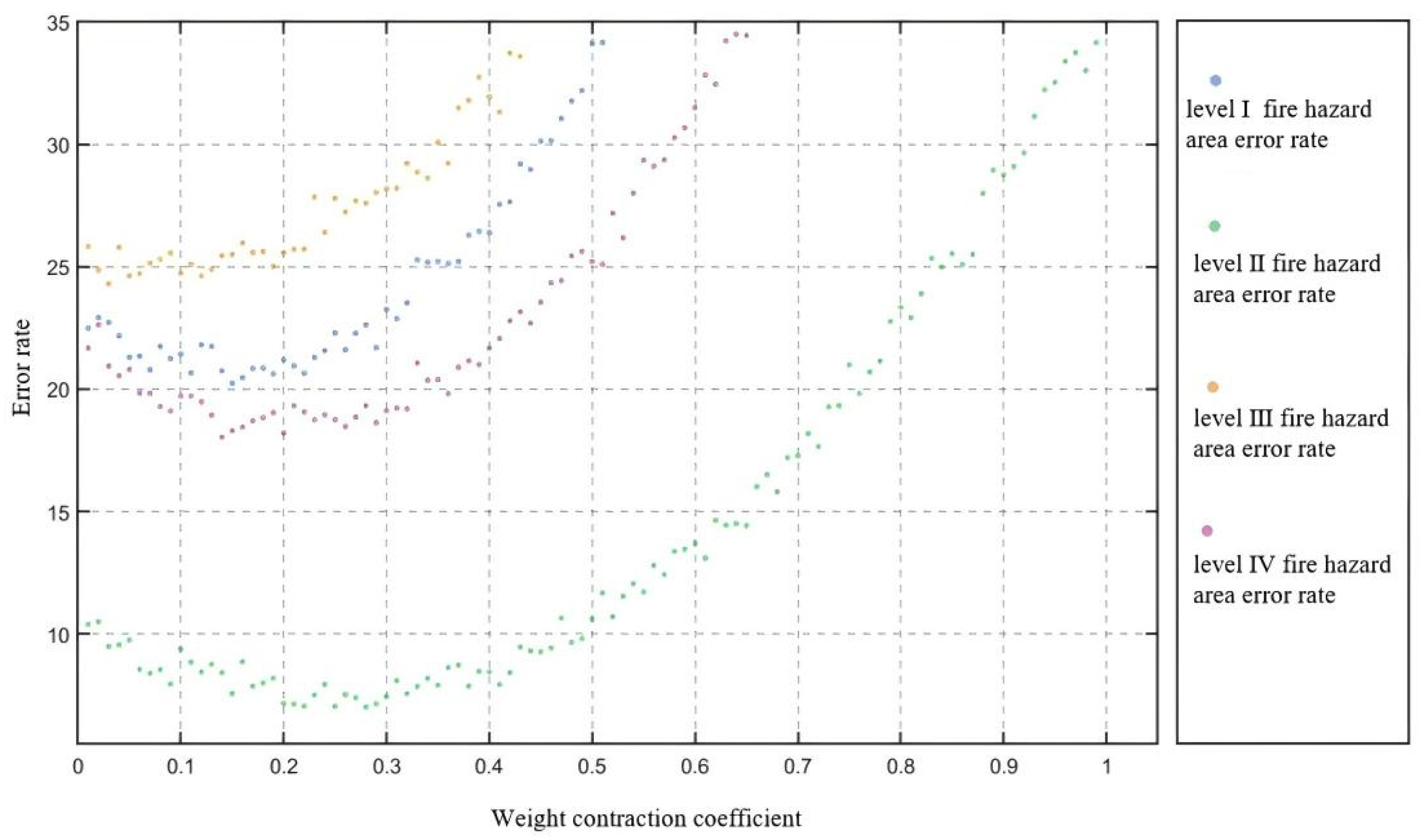

6.2. Model Parameter Optimization

The Sparrow Search Algorithm was applied to optimize three key hyperparameters of the XGBoost model: the number of base learners, the shrinkage weight, and the maximum tree depth. The optimization results demonstrated that setting the number of base learners to 200 yielded the best model performance. This ensemble of 200 trees collectively provides strong learning capacity, effectively compensating for the reduced contribution of individual trees, which results from the use of a low shrinkage weight, while still capturing complex relationships within the data. At the same time, this number helps mitigate overfitting risks that can arise from using too many weak learners, especially when combined with constrained, low shrinkage weights, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

Setting the shrinkage weight to 0.2 substantially improves model robustness. This parameter controls the contribution of each newly added tree to the overall prediction. Lower values result in more conservative updates to the model with each iteration. Such a configuration reduces the model’s sensitivity to noise and local fluctuations within individual trees, promoting a smoother and more generalized learning process that effectively captures underlying data patterns, as supported by the results illustrated in

Figure 7.

Constraining the maximum depth of individual decision trees to 7 levels plays a crucial role in controlling model complexity and improving generalization performance. This restriction effectively curbs excessive hierarchical expansion within tree structures. By enforcing a relatively shallow depth, the model is encouraged to avoid overfitting to idiosyncratic noise or overly specific rules in the training data. As a result, the algorithm focuses on capturing essential and generalizable feature interactions, those more likely to recur in unseen data, thereby significantly enhancing predictive generalization, as demonstrated in

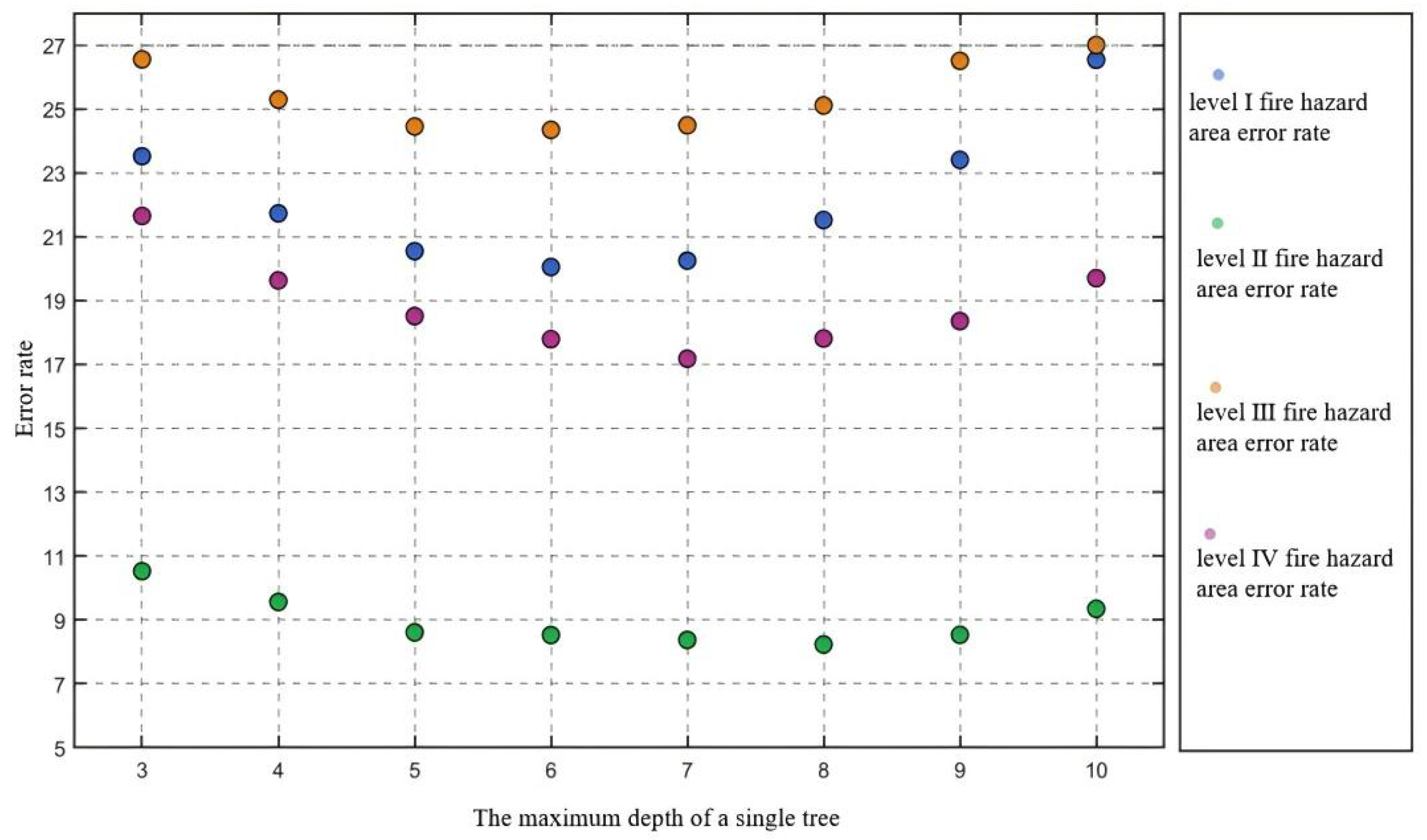

Figure 8.

The Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) was employed to systematically optimize the hyperparameters of the XGBoost prediction model. The parameter configuration of SSA was designed to balance global search capability and computational efficiency, specifically tailored for the multi-class fire point classification task.

The population size was set to 20, a value that provides sufficient individuals to effectively explore the hyperparameter space of XGBoost while avoiding the computational burden associated with excessively large populations. The maximum number of iterations was set to 50, supplemented by an early stopping criterion with a convergence threshold of 1 (iteration terminates if the optimal fitness remains unchanged for 5 consecutive generations). This configuration ensures adequate optimization cycles while preventing unnecessary computational expenditure.

Regarding population structure, the proportion of producers (explorers) was set to 0.2 and that of scroungers (followers) to 0.7. A safety threshold of 0.8 and an alert value of 0.6 were implemented. In this framework, producers are responsible for exploring new hyperparameter combinations globally, scroungers refine solutions based on discovered information, and alert sparrows trigger anti-predation behavior when approaching local optima, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s global search capability. A step control factor of 1.2 balances search flexibility and stability. Furthermore, the search ranges for key XGBoost hyperparameters were defined to align with the multi-class classification task (e.g., ‘max_depth’: 3–10, ‘learning_rate’: 0.01–0.3). The specific SSA parameter settings are detailed in

Table 3.

The XGBoost hyperparameters optimized by SSA achieved an optimal balance between model capacity and generalization performance, effectively adapting to the feature distribution and learning requirements of the classification task. In terms of tree structure control, the combination of ‘max_depth = 7’ and ‘min_child_weight = 3.2’ allows the model to capture complex nonlinear interactions while limiting leaf node sample weight to prevent overfitting to training noise. For regularization, parameters including ‘gamma = 0.42’ (minimum loss reduction for split), ‘reg_alpha = 0.18’ (L1 regularization), and ‘reg_lambda = 1.25’ (L2 regularization) collectively reduce model complexity. Regarding sampling strategy, ‘subsample = 0.85’ (row sampling), ‘colsample_bytree=0.91’, and ‘colsample_bylevel = 0.88’ (feature sampling) help mitigate feature redundancy and sample bias. The matched pair of ‘learning_rate = 0.184’ and ‘n_estimators = 382’ ensures stable convergence. The objective function was set to ‘multi:softmax’ for multi-class classification, with ‘merror’ as the evaluation metric. A fixed random seed (‘seed = 42’) was used for reproducibility. The optimized hyperparameters are listed in

Table 4.

The model exhibits a slight overfitting tendency, indicated by an average training accuracy approximately 4.37% higher than the validation accuracy. The confusion matrix reveals that, while prediction precision exceeds 90% for medium- and high-confidence fire points, the recall rate for low-confidence fire points (representing 16.7% of samples) is only 78%, reflecting limited generalization capability for minority classes. This risk primarily stems from the relatively high model complexity (‘max_depth = 7’, ‘n_estimators = 382’), which may lead to fitting noise in the training data. Although the sampling strategies (‘subsample = 0.85’, ‘colsample_bytree = 0.91’) mitigate overfitting to some extent, they do not completely eliminate sampling bias.

To address this, regularization terms (‘reg_alpha = 0.18’, ‘reg_lambda = 1.25’) introduced via SSA optimization helped constrain model complexity, improving test set accuracy by approximately 2.3%. Additionally, stratified random sampling was employed to balance sample proportions across fire point classes, and an early stopping strategy (patience = 10) was implemented to prevent over-iteration. These measures collectively contain the overfitting risk within an acceptable range.

6.3. Forest Fire Driver Assessment

The XGBoost model offers two metrics for evaluating the importance of independent variables: split frequency [

22] and predictive contribution [

23]. Although slight discrepancies exist in feature rankings between these metrics, the core driving factors maintain a consistent hierarchy of influence. Across both evaluation systems, topographic factors consistently emerge as the primary determinants of forest fires in Guangdong, followed by anthropogenic and meteorological factors, while vegetation-related variables exert the least influence, as illustrated in

Figure 9.

The study further enhanced model interpretability by employing SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis. This method fundamentally differs from the intrinsic variable importance metrics provided by the XGBoost framework, as it belongs to the domain of explainable machine learning. Its core strength lies in utilizing Shapley value theory to equitably quantify the marginal contribution of each feature to individual predictions, rather than merely indicating the frequency of feature usage during model training, thereby offering a more robust and theoretically grounded explanation. The analysis reveals that slope is the dominant influencing factor, with a SHAP value of 1.6166, substantially higher than that of other variables. This clearly indicates that terrain steepness is the primary determinant of forest fire risk levels. Meteorological factors also play a crucial role, with mean temperature (SHAP value: 0.4969) and mean precipitation (SHAP value: 0.3499) ranking third and fourth, respectively, confirming the significant influence of climatic conditions on fuel moisture content and fire spread dynamics. In contrast, anthropogenic factors exhibit a relatively limited impact, as evidenced by the SHAP value for population density being only 0.2051. The results are visually summarized in

Figure 10.

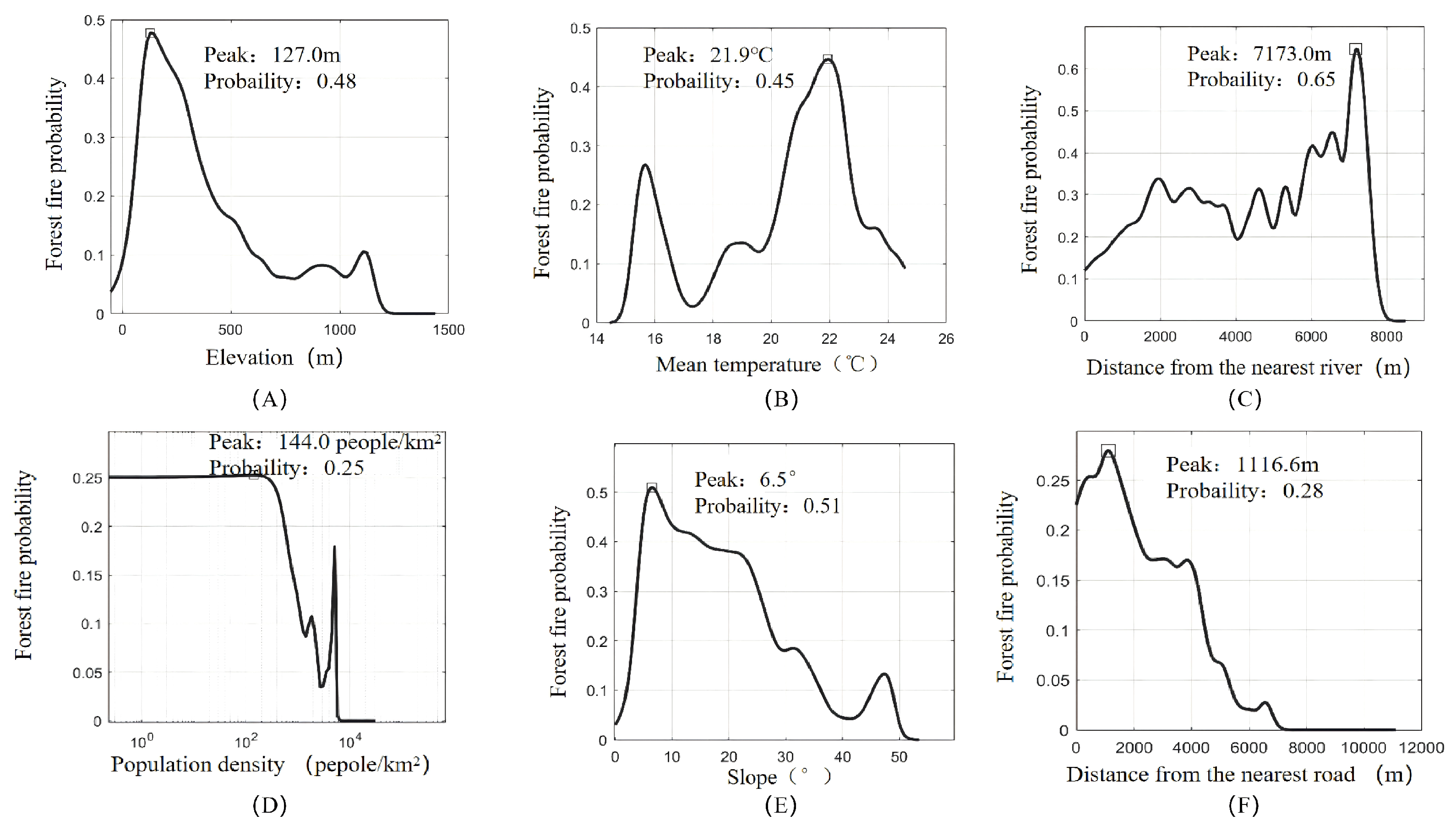

Partial dependence analysis of six key drivers, slope gradient, elevation, distance to roads, distance to rivers, mean temperature, and population density, revealed significant nonlinear relationships with fire occurrence probability, as synthesized in

Figure 11. Slope exhibited a unimodal influence, peaking at 6.5° before declining. Proximity to roads showed maximum ignition likelihood at 1116.6 m, with probability gradually decreasing beyond this threshold. Elevation reached its peak effect at 127 m, followed by a reduction in fire probability with further increases in altitude. Population density demonstrated a threshold effect, with fire probability dropping sharply beyond 144 people/km

2. Distance to rivers displayed non-monotonic fluctuations, culminating in a peak at 7173 m. Temperature revealed a bimodal pattern, with peaks at 15.8 °C and 21.9 °C bracketing a trough around 17.4 °C, a pattern potentially attributable to variations in humidity or vegetation moisture content. The decline beyond 21.9 °C suggests the presence of combustion-inhibiting factors.

The SSA-optimized XGBoost model, trained on the forest fire dataset [

12], achieved outstanding performance metrics: an overall accuracy of 90.4%, recall of 90.7%, precision of 90.2%, and an

score of 90.4%. These results confirm the model’s robust predictive capability and minimal false alarm rate.

6.4. Model Comparison and Evaluation

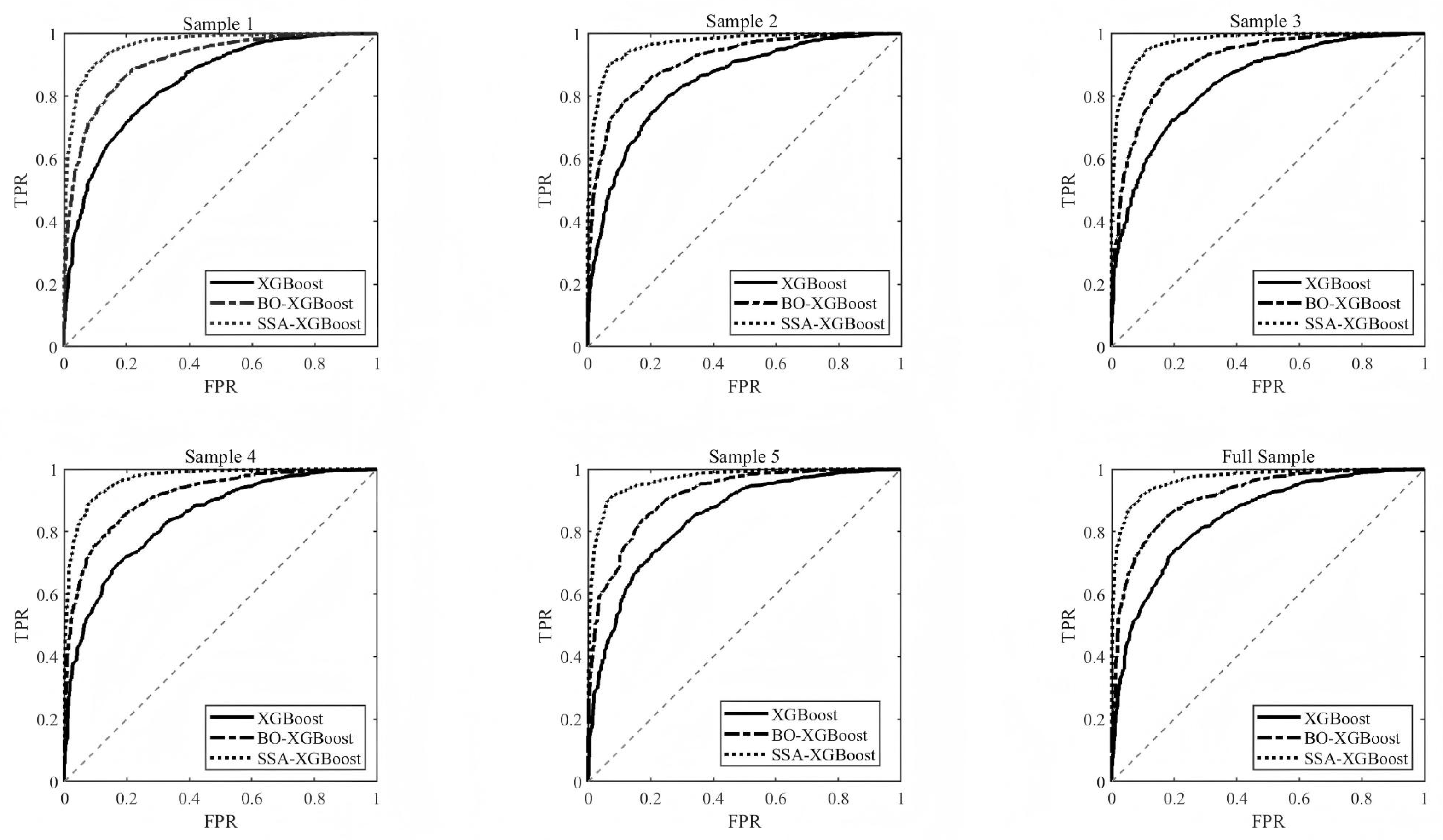

To comprehensively evaluate model performance, this study employed Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and prediction accuracy to compare three models: conventional XGBoost, Bayesian-optimized XGBoost (Bayes-XGBoost), and Sparrow Search Algorithm-optimized XGBoost (SSA-XGBoost). The ROC curves are presented in

Figure 12, and detailed prediction accuracy along with Area Under the Curve (AUC) values are summarized in

Table 5.

As shown in

Figure 12, the ROC curve of the SSA-XGBoost model lies closer to the upper-left corner of the coordinate system than that of the Bayes-XGBoost model, indicating a larger AUC and higher predictive accuracy. This demonstrates that, in terms of the ROC metric, the SSA optimization strategy outperforms the Bayesian optimization approach. Furthermore, the AUC values of both optimized models exceed that of the conventional XGBoost, confirming the positive effect of hyperparameter tuning on model performance.

According to

Table 5, the prediction accuracy of the SSA-XGBoost model ranges from 86.8% to 91.9%, which is higher than the 85.2–90.9% achieved by the Bayes-XGBoost model. In terms of AUC, the SSA-XGBoost model also shows superior values (0.961–0.965) compared to the Bayes-XGBoost model (0.913–0.915). These results collectively indicate that the SSA-XGBoost model exhibits better predictive performance and goodness-of-fit, making it more suitable for forest-fire occurrence prediction in Guangdong Province.

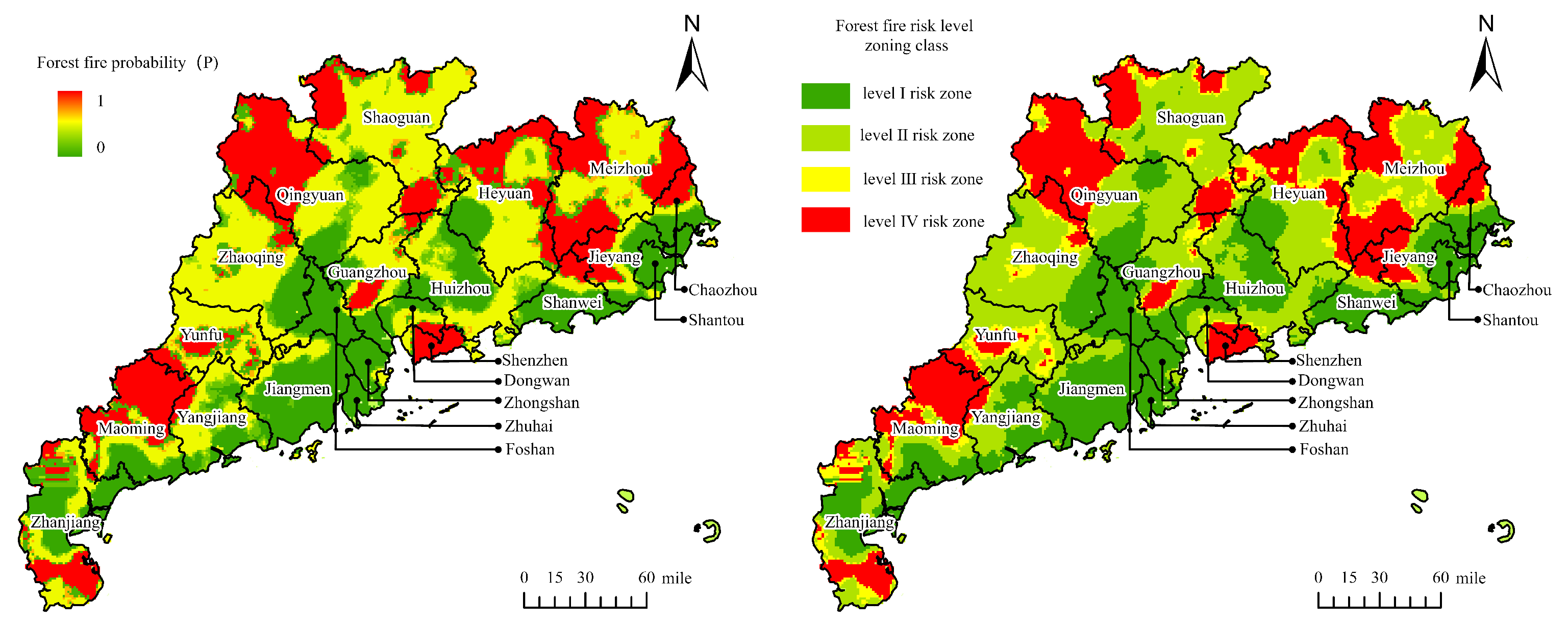

7. Guangdong Forest Fire Risk Zoning

Building upon the National Forest Fire Prevention Plan (2016-2025) [

24] and the industry standard LY/T1063-2008 [

25], this study addresses limitations such as overreliance on historical data and oversimplified six-factor frameworks by developing an XGBoost-based risk classification model that incorporates 10 key drivers spanning meteorological, vegetative, topographic, and anthropogenic domains. Model outputs were normalized to a continuous probability scale [0, 1] using histogram stretching, converting discrete classifications into spatially continuous probability surfaces. A four-tier risk zoning system was adopted: Level I (low risk, green), Level II (moderate risk, light green), Level III (high risk, yellow), and Level IV (extreme risk, red). Chromatic symbology conforming to cartographic standards [

26,

27] was applied to facilitate intuitive spatial interpretation of fire probability gradients throughout Guangdong.

Figure 13 shows that high-risk zones are predominantly concentrated in southwestern and northern Guangdong, with limited distribution in central regions. Cities characterized by Level IV and III risks include Qingyuan, Heyuan, Meizhou, Jieyang, Shenzhen, Maoming, and Zhanjiang. Level IV zones are also partially observed in Yunfu, Shaoguan, and Guangzhou. In contrast, Jiangmen, Yangjiang, Huizhou, and Foshan are classified mainly as Level I and II, indicating comparatively lower fire probabilities. This zoning pattern is largely consistent with the priority regions identified in the Guangdong Forest Fire Prevention Plan (2020–2030), which highlights Qingyuan, Heyuan, Meizhou, Shaoguan, Zhaoqing, Yunfu, Maoming, Zhanjiang, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Foshan. Foshan’s classification as low-risk in our model contrasts with its prominence in provincial planning, a discrepancy attributable to socioeconomic factors: despite a low historical fire frequency, the city’s high population density (exceeding 10,000 people/km

2), critical infrastructure, and urban–forest interfaces justify its policy emphasis. Our model assesses inherent combustibility based on historical ignitions and environmental drivers; Foshan’ maritime climate and limited forest cover (12.3%) result in fewer ignitions, leading to its lower risk ranking in our analysis.

Based on verified forest fire records from Guangdong Province between 2019 and 2024, and in accordance with the Regulations on Forest Fire Prevention [

28], this study conducted a statistical analysis of fire incidents. Over this six-year period, forest fires demonstrated a declining trend, comprising 0 exceptionally severe, 3 severe, 21 moderately severe, and 37 ordinary fire events (

Figure 14A). These data were utilized to validate the accuracy of the proposed risk zoning framework. In recent years, a noticeable concentration of fire occurrences has been observed. The western mountainous and hilly regions of Guangdong, particularly Zhaoqing and Maoming, were identified as key fire-prone areas. Simultaneously, the northern mountainous region exhibited a pronounced fire risk, with Shaoguan and Qingyuan experiencing the highest number of incidents (16 and 15 fires, respectively). Overall, 89% of high-frequency fire counties and cities were clustered in prefectures including Shaoguan, Qingyuan, Heyuan, and Meizhou (

Figure 14B). Notably, in nearly all affected counties and cities, ignition locations were heavily concentrated within the Level IV (highest risk) zones delineated in this study. This strong spatial consistency, even under the constraint of a limited validation dataset, substantiates the scientific reliability and practical applicability of the proposed risk zoning scheme.

Analysis of the forest fire risk zoning map (

Figure 13) for Guangdong Province reveals a distinct areal distribution across risk categories, as detailed in

Table 6. Level I (low risk) zones account for 31% of the provincial area, while Level II (moderate risk) zones cover 40% of the area. Together, these represent 71% of the territory classified as low-to-moderate risk. Level III (high risk) and Level IV (extreme risk) zones comprise 9% and 20% of the land area, respectively, totaling 29% identified as high risk, nearly one-third of the entire province. As a key forest region in southern China, Guangdong exhibits a substantial distribution of high-risk areas despite the overall predominance of lower-risk categories. This spatial pattern highlights considerable fire prevention challenges, necessitating targeted monitoring infrastructure and adaptive management strategies focused on high-risk regions. Such measures are imperative to mitigate fire vulnerabilities intensified by the subtropical monsoon climate and to ensure the ecological security of its forest ecosystems.

8. Discussion

This study employs an XGBoost model incorporating meteorological, topographic, vegetation, and anthropogenic factors to identify key drivers of forest fires and establish a risk zoning framework for Guangdong Province [

29,

30]. The region is characterized predominantly by gentle terrain, with low hills in the northern, eastern, and western areas, and plains in the central and southern regions. Forest fires occur most frequently at low elevations, on gentle slopes, and on southeastern-facing aspects, particularly in the foothill zones of northern and eastern Guangdong. Mechanistically, gentle slopes facilitate the spread of fires [

12,

31], while prevailing southeastern winds combined with dry conditions promote the propagation of surface fires. Additionally, foothill areas experience intensive human activities, such as discarded cigarettes and ritual burning, which significantly increase ignition risks. Proximity to roads and rivers further elevates fire probability, reflecting direct anthropogenic influence [

21,

32].

Meteorological factors, particularly temperature, precipitation, and sunshine duration, play a critical role: high temperatures and arid conditions intensify evapotranspiration, thereby elevating fire risk [

33], while daytime heating reduces fuel moisture, contributing to diurnal variation in ignition probability. Vegetation analysis indicates that fire likelihood is higher in areas with medium-to-low vegetation coverage [

30,

34]. Combustible biomass, primarily Masson pine, eucalyptus, Chinese fir, and understory shrubs such as downy rosemyrtle and false staghorn fern, forms extensive fire-prone fuel beds [

34]. Among these, grasses and shrubs exhibit higher ignitability compared to trees.

Anthropogenic influences demonstrate complex effects: densely populated areas exhibit reduced fire incidence, likely due to advanced fire management systems, whereas sparsely populated regions face higher risks resulting from insufficient prevention awareness [

29,

30,

35,

36,

37]. These insights provide valuable guidance for enhancing fire prevention strategies in Guangdong.

In terms of modeling, the Sparrow Search Algorithm-optimized XGBoost model demonstrates superior accuracy in capturing the nonlinear relationships among fire-driving factors in Guangdong while also providing robust variable importance rankings. Unlike continuous-output models, its categorical predictions eliminate the need for subjective probability thresholds, thereby offering more straightforward support for disaster decision-making. Furthermore, classification models such as this exhibit greater tolerance to variations in input data precision, a particularly advantageous feature given Guangdong’s complex and fluctuating climatic conditions.

9. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive analysis and predictive assessment of forest fire patterns in Guangdong Province, adopting a multi-faceted methodology to support and refine regional fire management strategies. By integrating MOD14A1 active fire data with variables spanning climatic, topographic, vegetation, and socioeconomic domains, we utilized kernel density estimation and spatial autocorrelation techniques to delineate spatiotemporal dynamics and regional clustering behavior of forest fires. A Sparrow Search Algorithm-optimized XGBoost model was developed to achieve high-precision spatial risk prediction and facilitate scientifically grounded risk zoning. The principal findings are summarized as follows:

1. Forest fires in Guangdong display marked spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Considerable interannual variability was observed, with monthly incidence heavily concentrated from February to April and September to November. March exhibited the highest fire frequency, accounting for 16.32% of total incidents. Spatial analysis revealed strong aggregation patterns, particularly in northern, western, and partial central regions, including Guangzhou, Zhaoqing, Zhanjiang, Qingyuan, Maoming, Meizhou, Shaoguan, and Heyuan, where medium-high and high-density fire clusters cover 15.71% of the provincial area.

2. The SSA-optimized XGBoost model attained optimum performance with the parameter set: 200 base learners, a shrinkage weight of 0.2, and a maximum tree depth of 7. Evaluation metrics demonstrated high predictive accuracy, including an Overall Accuracy of 90.4%, Recall of 90.7%, Precision of 90.2%, and an -score of 90.4%.

3. Key drivers of forest fire occurrence were identified as slope gradient, distance to roads, proximity to waterways, mean temperature, population density, and elevation. Topographic factors, most notably slope, emerged as the dominant influencing category.

4. Level III and IV risk zones, representing high and extreme fire risk, collectively account for 29% of Guangdong’s land area, underscoring the substantial spatial extent of fire-prone regions. These areas necessitate targeted prevention strategies and enhanced resource allocation to mitigate fire management challenges. Validation against observed fire records from 2019 to 2024 confirmed strong spatial concordance between predicted high-risk zones and actual ignition hotspots, affirming the reliability and practical applicability of the proposed zoning framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and C.Y.; methodology, H.W. and C.Y.; software, J.W.; validation, H.W., C.Y. and J.W.; formal analysis, H.W.; investigation, C.Y. and J.W.; resources, H.W.; data curation, H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W., C.Y. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, H.W., C.Y. and J.W.; visualization, H.W. and J.W.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W. and C.Y.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52505584), the Research Projects at the Academy Level of China Fire and Rescue Institute (Grant No. XFKYY202513 and XFKYY202510), the Teaching Reform Projects at the Academy Level of China Fire and Rescue Institute (Grant No. 2025RGZN01Z) and the General Project of Beijing Higher Education Society in 2025 (Grant No. MS2025298) This work was an interim research achievement of the Research Project on Student Club Work in Beijing Universities (Grant No. BJST2025YB14).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the anonymous referees and editors for their valuable suggestions and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kirana, A.P.; Astiningrum, M.; Vista, C.B.; Bhawiyuga, A.; Amrozi, A.N. Spatio-Temporal Pattern Analysis of Forest Fire in Malang based on Remote Sensing using K-Means Clustering. Int. J. Multidiscip. Appl. Bus. Educ. Res. 2023, 4, 3046–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Analysis of spatial clustering patterns of fire misidentification through spatial autocorrelation analysis: Focusing on Gyeongsangbuk-do. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2023, 23, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Q. Study on the driving factors of the spatiotemporal pattern in forest lightning fires and 3D fire simulation based on cellular automata. Forests 2024, 15, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Cha, H.-s.; Jiang, S. The Prediction of Fire Disaster Using BIM-Based Visualization for Expediting the Management Process. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Ji, R. Optimising hurricane shelter locations with smart predict-then-optimise framework. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 2905–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, C.-Y.; Liu, C.-Y. Predictive Modeling of Fire Incidence Using Deep Neural Networks. Fire 2024, 7, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, A.; Baruque, B.; Pérez-Lancho, B.; Corchado, E.; Corchado, J.M. Forest Fire Evolution Prediction Using a Hybrid Intelligent System. In Balanced Automation Systems for Future Manufacturing Networks; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, S.; Arashpour, M.; Golafshani, E.M.; Cruz, M.G.; Rajabifard, A.; Bai, Y. Prediction of wildfire rate of spread in grasslands using machine learning method. Environ. Model. Softw. 2022, 156, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umamaheswari, R.; Shanmuga Priya, S.; Ganesan, R.; Uma, S. Forest Fire Detection using CNN-RF and CNN-XGBOOST Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2023 Third International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Energy (ICAIS), Coimbatore, India, 2–4 February 2023; pp. 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsias, N.; Balatsos, P.; Kalabokidis, K. Fire occurrence zones: Kernel density estimation of historical wildfire ignitions at the national level, Greece. J. Maps 2014, 10, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Han, G.; Zhou, L. Forest fire prediction models for Guangdong Province based on GIS and multiple machine learning algorithms. J. For. Eng. 2024, 9, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, Q.J.; Lei, J.J. Optimization design of non-pressure tank structure based on simulated-annealing algorithmm. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2024, 19, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Ye, S.; Yi, W. Trajectory optimization of glide guidance projectile based on PSO-hpRPM hybrid algorithm. Control Decision 2025, 40, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Fu, Q.; Zhou, Y. Improved Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm for Heliostats Field Layout. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xi, J.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, K.; Song, F.; Jiang, Z.; Liao, B. Multi-strategy Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm for Solving High Dimensional Optimization and Feature Selection Problems. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 24, 13450–13466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y. Research on Expressway Engineering Cost Prediction Based on Hybrid ISSA-XGBoost. J. Eng. Stud. 2024, 2024, 1–14. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.5780.TB.20240924.1557.004 (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Luo, Q.; Liu, F.; Zhu, K.; Yang, L.; Zhao, S. Spatiotemporal differentiation and spatial autocorrelation analysis of landscape ecological risk in the Chishui River Basin (Guizhou section). Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 32, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Sarma, K.; Sharma, R. Using Moran’s I and GIS to study the spatial pattern of land surface temperature in relation to land use/cover around a thermal power plant in Singrauli district, Madhya Pradesh, India. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2019, 15, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, B.; Luo, J.; Zuo, Z. Temporal and spatial variation and risk zoning of forest fires in Liang shan Yi Autonomous Prefecture. J. Northwest Univ. Natural Sci. Ed. 2024, 52, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Cai, J.; Qiu, J.; Wang, D.; Lin, K.; Yang, K.; Zeng, Q. Forest fire prediction based on soil moisture and meteorological factors: Taking Guangdong Province as an example. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2021, 41, 1676–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Xie, W. Leak localization method for gas pipeline based on TPE-XGBoost modeling. CIESC J. 2025, 76, 5510–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xu, X.; Yang, X.; Cui, B.; Chen, H.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, N.; Meng, F. Prediction of nitrogen leaching from winter-wheat production in North China based on random forest and XGBoost. China Environ. Sci. 2024, 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Fan, L.A.; Liu, M. Implementation of the National Forest Fire Prevention Plan (2016–2025). J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2017, 37, 2+129. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=f0DSObGwzqiRY7J0aYMVTzNeC0SLU7X0UAaRN3YY_zdifYlaSt7d9prLfRr9s3C5eiuUAIyfc0DO1y3L-SPXRgxRUauyoD4dJNaz40pEJ0STbKWRI45xNZgT92OPCosjpz2vpF9dnmiD8YiSnvRlPwNJoa4JGCL2v9lDB75B4k7FcHk7wgWFlA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 June 2017).

- Forest Fire Prevention Office of the Ministry of Forestry. National Forest Fire Risk Classification Grades: LY 1063-1992; China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 1992. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=f0DSObGwzqhsOI2GR9UCdfmAZrGMEeyweM9RysIcYsD96a0Tp0XWQvjxmkfcZv8pXcT8qlVodXR0isas9tuJFTecqKP_VLZYNtnpCoQDHd57r46y5MHpoLGxM_GgIQfJ4tTGRiHyD74RDQLaZvuwpB_tx6O9rCi4VM8B8DUsX3MKxWp15WpQLA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 26 March 1992).

- An, J.; Feng, Z.; Ma, T.; Gao, K. Zoning of forest fire risk levels in the Hechuan District of Chongqing based on GIS grid. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2022, 42, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.G.; Pan, J.H.; Li, J.F. Assessment and zoning of fire risk in Shanxi Province based on spatial Logistic model. Pratacultural Sci. 2016, 33, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulations on Forest Fire Prevention; Gazette of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1988; Volume 3, pp. 81–88. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=f0DSObGwzqjajURnTQupAOGsV73TJ72PqwdgT5aZ8Lh8MJ-XYN5-D1JyVockNSRdCywSafrKfpYLxTGdwAbeZhJbe0iD_Bjd6SXuwyFOpEap4JLJ7jMfLi6UjgO_s9s1gboUrK3PZO6oXFj2omwfCv2P2UwelTosjLqgKV4Mp_OQ9NB2l3lNRg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 16 January 1998).

- Ju, W.; Wei, L.; Peng, B.; Li, C.; Pan, T. Study on Driving Factors and Prediction Model of Forest Fire in Guangxi. For. Grassl. Resour. Res. 2023, 5, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q. Study on the forest fire risk early warning in Guangdong Province based on MODIS. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2021, 2021, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Gong, K.; Zhang, S.; He, T.; Chen, F.; Sun, Y.; Feng, Z. Forest Fire Division by Using MODIS Data Based on the Tenoporal-Spatial Variation Law. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2013, 33, 2472–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.X.; Huang, Y.C.; Zhao, G.L. Study on forest fire occurrence prediction model and fire risk zoning in the Qinling Mountains. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2025, 40, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Wang, Z.; Lai, C.; Chen, X.; Yang, B.; Zhao, S.; Bai, X. Flood hazard risk assessment model based on random forest. J. Hydrol. 2015, 527, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Guo, Z.; Li, X.; Huang, W. Spatial-temporal Variation of Vegetation NDVI in Guangdong Province from 2001 to 2019. Radio Eng. 2021, 51, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xue, C.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Q.; Yang, C.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y. Diversity of Typical Vegetation Types in Guangdong Province Based on Continuous Forest Inventory in 2017. For. Environ. Sci. 2020, 36, 60–65. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=f0DSObGwzqiyl8SxLHMpRTWSvRq7X4DlvF9LE1iAwlE-Gi-NolHi6VbjzEcd8ryFkxRXibo6b9tjA1Hoge72EK27plVttfA2xx5TG_Oj-Ei5XiX2pTejZ4lWXWEiZ80A-VSWnGlDNlbllKqZY-aNqxQwd3g4kQYIdJ_TFjLTWrYF1OQM3oXeDA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Jones, M.W.; Veraverbeke, S.; Andela, N.; Doerr, S.H.; Kolden, C.; Mataveli, G.; Pettinari, M.L.; Quéré, C.L.; Rosan, T.M.; Werf, G.R.; et al. Global rise in forest fire emissions linked to climate change in the extratropics. Science 2024, 386, eadl5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Song, Y. A high-resolution emission inventory of crop burning in fields in China based on MODIS Thermal Anomalies/Fire products. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 50, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geographical location and forest distribution map of Guangdong province.

Figure 1.

Geographical location and forest distribution map of Guangdong province.

Figure 2.

Interannual and monthly variations of forest fires in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 2.

Interannual and monthly variations of forest fires in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of forest fire kernel density in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of forest fire kernel density in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution patterns of forest fires in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution patterns of forest fires in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of geographical locations and historical fire incidents in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of geographical locations and historical fire incidents in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Figure 6.

The relationship between the number of base learners and error rate.

Figure 6.

The relationship between the number of base learners and error rate.

Figure 7.

The relationship between weight contraction coefficient and error rate.

Figure 7.

The relationship between weight contraction coefficient and error rate.

Figure 8.

The relationship between the maximum depth of a single tree and error rate.

Figure 8.

The relationship between the maximum depth of a single tree and error rate.

Figure 9.

Importance ranking of forest fire driving factors in Guangdong.

Figure 9.

Importance ranking of forest fire driving factors in Guangdong.

Figure 10.

SHAP feature importance.

Figure 10.

SHAP feature importance.

Figure 11.

(A–F) is a partial partial dependence of some forest fire driving factors in Guangdong.

Figure 11.

(A–F) is a partial partial dependence of some forest fire driving factors in Guangdong.

Figure 12.

ROC curves of three models.

Figure 12.

ROC curves of three models.

Figure 13.

Spatial distribution of forest fire probability and risk level zoning class in Guangdong based on XGBoost model.

Figure 13.

Spatial distribution of forest fire probability and risk level zoning class in Guangdong based on XGBoost model.

Figure 14.

Accurate fire event statistics based on years and cities in Guangdong from 2019 to 2024.

Figure 14.

Accurate fire event statistics based on years and cities in Guangdong from 2019 to 2024.

Table 1.

MODIS fire mask pixel-level meaning table.

Table 1.

MODIS fire mask pixel-level meaning table.

| Level | Meaning |

|---|

| 0–2 | Invalid pixel |

| 3 | Water area |

| 4 | Cloud |

| 5 | Bare land |

| 6 | Unknown pixel |

| 7 | Low-confidence fire detection |

| 8 | Moderate-confidence fire detection |

| 9 | High-confidence fire detection |

Table 2.

Distribution of forest fire kernel density by city in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

Table 2.

Distribution of forest fire kernel density by city in Guangdong from 2014 to 2023.

| Serial Number | Country | Low Density Areas | Middle-Low Density Areas | Medium Density Areas | Medium-High Density Areas | High Density Areas |

|---|

| 1 | Meizhou | 3635.60 | 7120.74 | 1813.74 | 1028.87 | 394.47 |

| 2 | Shenzhen | 858.07 | 614.07 | 215.53 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Shanwei | 443.27 | 1911.34 | 1732.40 | 361.93 | 0 |

| 4 | Zhuhai | 1394.87 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Heyuan | 4005.67 | 3106.94 | 3700.67 | 1720.20 | 1272.87 |

| 6 | Shantou | 1606.34 | 150.47 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Yangjiang | 138.27 | 3891.80 | 1846.27 | 1004.47 | 0 |

| 8 | Foshan | 1500.60 | 736.07 | 435.13 | 654.73 | 0 |

| 9 | Zhangqing | 268.40 | 4875.94 | 4530.27 | 2252.94 | 1232.20 |

| 10 | Guangzhou | 2212.27 | 984.13 | 707.60 | 866.20 | 1638.87 |

| 11 | Huizhou | 4847.47 | 4042.27 | 984.13 | 24.40 | 0 |

| 12 | Shaoguan | 8296.01 | 4534.34 | 2240.74 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | Jieyang | 760.47 | 2326.14 | 1382.67 | 162.67 | 0 |

| 14 | Yunfu | 101.67 | 2358.67 | 2700.27 | 1366.40 | 345.67 |

| 15 | Zhongshan | 1529.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | Qingyuan | 3131.34 | 7490.81 | 3192.34 | 2354.60 | 675.07 |

| 17 | Jiangmen | 1903.20 | 3371.27 | 2395.27 | 467.67 | 0 |

| 18 | Dongwan | 1289.13 | 610.00 | 130.13 | 113.87 | 24.40 |

| 19 | Zhanjiang | 2537.60 | 2309.87 | 2472.54 | 1232.20 | 1537.20 |

| 20 | Maoming | 272.47 | 2875.14 | 3180.14 | 3045.94 | 467.67 |

| 21 | Chaozhou | 1691.74 | 736.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Area ratio/% | 27.48% | 35.01% | 21.80% | 10.79% | 4.92% |

Table 3.

Parameter settings for the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA).

Table 3.

Parameter settings for the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA).

| Parameter Category | Parameter Name | Symbol | Value |

|---|

| Population Setting | Population Size | ‘population_size’ | 20 |

| Iteration Control | Maximum Iterations | ‘max_iter’ | 50 |

| Stopping Criterion | Convergence Threshold | ‘convergence_thres’ | 1.00 |

| Population Structure | Producer Ratio | ‘producer_rate’ | 0.2 |

| Population Structure | Scrounger Ratio | ‘scrounger_rate’ | 0.7 |

| Behavioral Control | Safety Threshold | ‘safety_threshold’ | 0.8 |

| Behavioral Control | Alert Value | ‘alert_value’ | 0.6 |

| Search Strategy | Step Control Factor | ‘step_factor’ | 1.5 |

Table 4.

Optimized hyperparameters for the XGBoost model.

Table 4.

Optimized hyperparameters for the XGBoost model.

| Parameter Category | Parameter Name | Symbol | Optimized Value | Search Range |

|---|

| Tree Structure | Max Depth | ‘max_depth’ | 7 | 3–10 |

| Tree Structure | Min Child Weight | ‘min_child_weight’ | 3.2 | 1–5 |

| Regularization | Gamma | ‘gamma’ | 0.42 | 0–1 |

| Regularization | L1-Regularization (Alpha) | ‘reg_alpha’ | 0.18 | 0–1 |

| Regularization | L2-Regularization (Lambda) | ‘reg_lambda’ | 1.25 | 0–2 |

| Sampling | Subsample Ratio | ‘subsample’ | 0.85 | 0.6–1.0 |

| Sampling | Colsample by Tree | ‘colsample_bytree’ | 0.91 | 0.7–1.0 |

| Sampling | Colsample by Level | ‘colsample_bylevel’ | 0.88 | 0.7–1.0 |

| Learning Control | Learning Rate | ‘learning_rate’ | 0.184 | 0.01–0.3 |

| Ensemble Control | Number of Estimators | ‘n_estimators’ | 382 | 100–500 |

| Training Control | Max Delta Step | ‘max_delta_step’ | 0.8 | 0–1 |

Table 5.

Model performance comparison across different samples (AUC and prediction accuracy).

Table 5.

Model performance comparison across different samples (AUC and prediction accuracy).

| Sample | Model | AUC | Training Acc. (%) | Test Acc. (%) |

|---|

| | XGBoost | 0.854 | 80.2 | 77.3 |

| Sample 1 | Bayesian-Optimized XGBoost | 0.913 | 88.4 | 85.2 |

| | SSA-Optimized XGBoost | 0.961 | 90.3 | 88.6 |

| | XGBoost | 0.845 | 83.5 | 80.2 |

| Sample 2 | Bayesian-Optimized XGBoost | 0.914 | 87.8 | 83.4 |

| | SSA-Optimized XGBoost | 0.963 | 91.6 | 88.2 |

| | XGBoost | 0.846 | 82.7 | 79.5 |

| Sample 3 | Bayesian-Optimized XGBoost | 0.913 | 90.9 | 87.1 |

| | SSA-Optimized XGBoost | 0.965 | 91.1 | 87.3 |

| | XGBoost | 0.843 | 79.4 | 78.7 |

| Sample 4 | Bayesian-Optimized XGBoost | 0.914 | 88.1 | 85.2 |

| | SSA-Optimized XGBoost | 0.963 | 89.7 | 86.8 |

| | XGBoost | 0.845 | 80.1 | 76.2 |

| Sample 5 | Bayesian-Optimized XGBoost | 0.915 | 87.9 | 86.1 |

| | SSA-Optimized XGBoost | 0.964 | 90.5 | 87.9 |

| | XGBoost | 0.845 | 81.3 | 78.1 |

| Full Sample | Bayesian-Optimized XGBoost | 0.914 | 89.6 | 87.4 |

| | SSA-Optimized XGBoost | 0.964 | 91.9 | 88.3 |

Table 6.

The area and proportion of different forest fire risk levels in Guangdong.

Table 6.

The area and proportion of different forest fire risk levels in Guangdong.

| Serial Number | Fire Risk Level Zone | Area/km2 | Area Percentage/% |

|---|

| 1 | Level I risk zone | 55,647.74 | 31% |

| 2 | Level II risk zone | 70,634.37 | 40% |

| 3 | Level III risk zone | 15,850.49 | 9% |

| 4 | Level IV risk zone | 35,851.51 | 20% |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |