Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the Family Empowerment Scale Among Latinx Parents of Children with Disabilities: An Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling

1.2. Previous Research on the Family Empowerment Scale

1.3. Purpose of This Study

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measure

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. CFA Models

3.3. ESEM Models

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. Psychometric Properties of FES Scores in Latinx Parents of Children with IDD

4.2. Three-Factor Model of FES for Latinx Parents of Children with IDD

4.3. Proposed Revisions to FES Item Wording and Structure

4.4. Suggested Practices for Factor Analysis

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rios, K.; Burke, M.M.; Aleman-Tovar, J. A study of the families included in Receiving Better Special Education Services (FIRME) Project for Latinx families of children with autism and developmental disabilities. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 3662–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, P.E.; DeChillo, N.; Friesen, B.J. Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: A brief questionnaire. Rehabil. Psychol. 1992, 37, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayslip, B., Jr.; Smith, G.C.; Montoro-Rodriguez, J.; Streider, F.H.; Merchant, W. The utility of the family empowerment scale with custodial grandmothers. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2017, 36, 320–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorenmaa, M.; Perälä, M.L.; Halme, N.; Kaunonen, M.; Åstedt-Kurki, P. Associations between family characteristics and parental empowerment in the family, family service situations and the family service system. Child Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.N.; Curtis, W.J.; Ellis, C.R.; Nicholson, M.W.; Villani, T.M.; Wechsler, H.A. Psychometric evaluation of the Family Empowerment Scale. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 1995, 3, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, E.W.; van den Hoogen, A.; van Eerden, I.C.; Hafsteinsdóttir, T.; Ketelaar, M. Perspectives of parents and nurses on the content validity of the Family Empowerment Scale for parents of children with a chronic condition: A mixed-methods study. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Yokoyama, K. Validity and reliability of the Family Empowerment Scale for caregivers of adults with mental health issues. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 23, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerkensmeyer, J.E.; Perkins, S.M.; Scott, E.L.; Wu, J. Depressive symptoms among primary caregivers of children with mental health needs: Mediating and moderating variables. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2008, 22, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huscroft-D’Angelo, J.; January, S.A.A.; Duppong Hurley, K.L. Supporting parents and students with emotional and behavioral disorders in rural settings: Administrator perspectives. Rural. Spec. Educ. Q. 2018, 37, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L.; Lomas, T.; van de Weijer, M.P.; Passmore, H.A.; Joshanloo, M.; Harter, J.; Ishikawa, Y.; Lai Al Kitagawa, T.; Chen, D.; Kawakami, T.; et al. Towards a greater global understanding of wellbeing: A proposal for a more inclusive measure. Int. J. Wellbeing 2020, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P.S.; Tarraf, W.; Marsack, C. Family Quality of Life Survey (FQOLS-2006): Evaluation of Internal Consistency, Construct, and Criterion Validity for Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Families. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2018, 38, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F.; Zheng, Q.; Kramer, J.; Reichow, B.; Snyder, P. A systematic review of the measurement properties of the Family Empowerment Scale. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, A.J.; Arens, A.K.; Marsh, H.W. A bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling framework for the identification of distinct sources of construct-relevant psychometric multidimensionality. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2016, 23, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2009, 16, 397–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Muthén, B.; Asparouhov, T.; Lüdtke, O.; Robitzsch, A.; Morin, A.J.; Trautwein, U. Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: Application to students’ evaluations of university teaching. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2009, 16, 439–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.; Hughes, D.J. Exploratory structural equation modeling of personality data. Assessment 2014, 21, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boztepe, H.; Çınar, S.; Kanbay, Y.; Acımış, B.; Özgür, F.; Terzioglu, F. Validity and reliability of the Family Empowerment Scale for parents of children with cleft lip and/or palate. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, T.D.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y. semTools: Useful Tools for Structural Equation Modeling. R Package Version 0.5-7. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canino, G.; Vila, D.; Normand, S.L.T.; Acosta-Pérez, E.; Ramírez, R.; García, P.; Rand, C. Reducing asthma health disparities in poor Puerto Rican children: The effectiveness of a culturally tailored family intervention. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Grayson, D. Goodness of fit in structural equation modeling. In Contemporary Psychometrics. A Festschrift to Roderick P. McDonald; Maydeu-Olivares, A., McArdle, J., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 275–340. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Morin, A.J.; Parker, P.D.; Kaur, G. Exploratory structural equation modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; Li, C.; Fulton, K.; Cheung, W.C. A Pilot Study of the Effectiveness and Feasibility of an Early Intervention Leadership Program for Families of Children with Disabilities. J. Early Interv. 2024, 47, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandalos, D.L. Relative Performance of Categorical Diagonally Weighted Least Squares and Robust Maximum Likelihood Estimation. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2014, 21, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, C.G.; Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Gallardo-Pujol, D. Factor Analysis with Ordinal Indicators: A Monte Carlo Study Comparing DWLS and ULS Estimation. Struct. Equ. Model. 2009, 16, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All Parents | Mean: Scale | Mean: Item | SD: Scale | SD: Item | Alpha | Omega | Range: Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Empowerment | 114.32 | 3.36 | 24.86 | 0.73 | 0.951 | 0.962 | 34–170 |

| Family | 41.72 | 3.48 | 9.65 | 0.80 | 0.903 | 0.906 | 12–60 |

| Service | 41.88 | 3.49 | 9.52 | 0.79 | 0.894 | 0.899 | 12–60 |

| Community | 30.73 | 2.56 | 7.91 | 0.66 | 0.833 | 0.840 | 10–50 |

| FES | Description of Items |

|---|---|

| Empower 1 | Parents’ Right to Approve Child Services |

| Empower 2 | Handling child issues effectively |

| Empower 3 | Feeling capable of enhancing children’s services in my community |

| Empower 4 | Confidence in assisting in a child’s growth and development. |

| Empower 5 | Being aware of the Steps for Concerned Child Services |

| Empower 6 | Ensuring professionals understand my views on my child’s service needs. |

| Empower 7 | Being aware of what to do when problems arise. |

| Empower 8 | Contacting legislators about children’s issues. |

| Empower 9 | Feeling that family life is under control. |

| Empower 10 | Understanding how the children’s service system is organized. |

| Empower 11 | Making good decisions about what services my child needs. |

| Empower 12 | Working with professionals to decide on services. |

| Empower 13 | Staying in regular contact with service providers. |

| Empower 14 | Having ideas about the ideal service system for children. |

| Empower 15 | Helping other families access needed services. |

| Empower 16 | Seeking information to better understand my child. |

| Empower 17 | Belief that parents can influence services. |

| Empower 18 | Valuing my opinion equally with professionals in service decisions. |

| Empower 19 | Expressing my opinions about services being provided. |

| Empower 20 | Providing feedback to agencies and government on improving services. |

| Empower 21 | Confidence in solving problems with my child. |

| Empower 22 | Knowing how to get agency administrators or legislators to listen. |

| Empower 23 | Knowing what services my child needs. |

| Empower 24 | Awareness of parent and child rights under special education law. |

| Empower 25 | Belief that my parenting experience can improve services. |

| Empower 26 | Ability to ask for help when needed with family problems. |

| Empower 27 | Learning new ways to help my child grow and develop. |

| Empower 28 | Taking initiative to find services for my child and family. |

| Empower 29 | Focusing on my child’s strengths as well as problems. |

| Empower 30 | Understanding the service system my child is involved in. |

| Empower 31 | Taking action when problems arise involving my child. |

| Empower 32 | Belief that professionals should ask my input on services. |

| Empower 33 | Understanding my child’s disorders. |

| Empower 34 | Feeling that I am a good parent. |

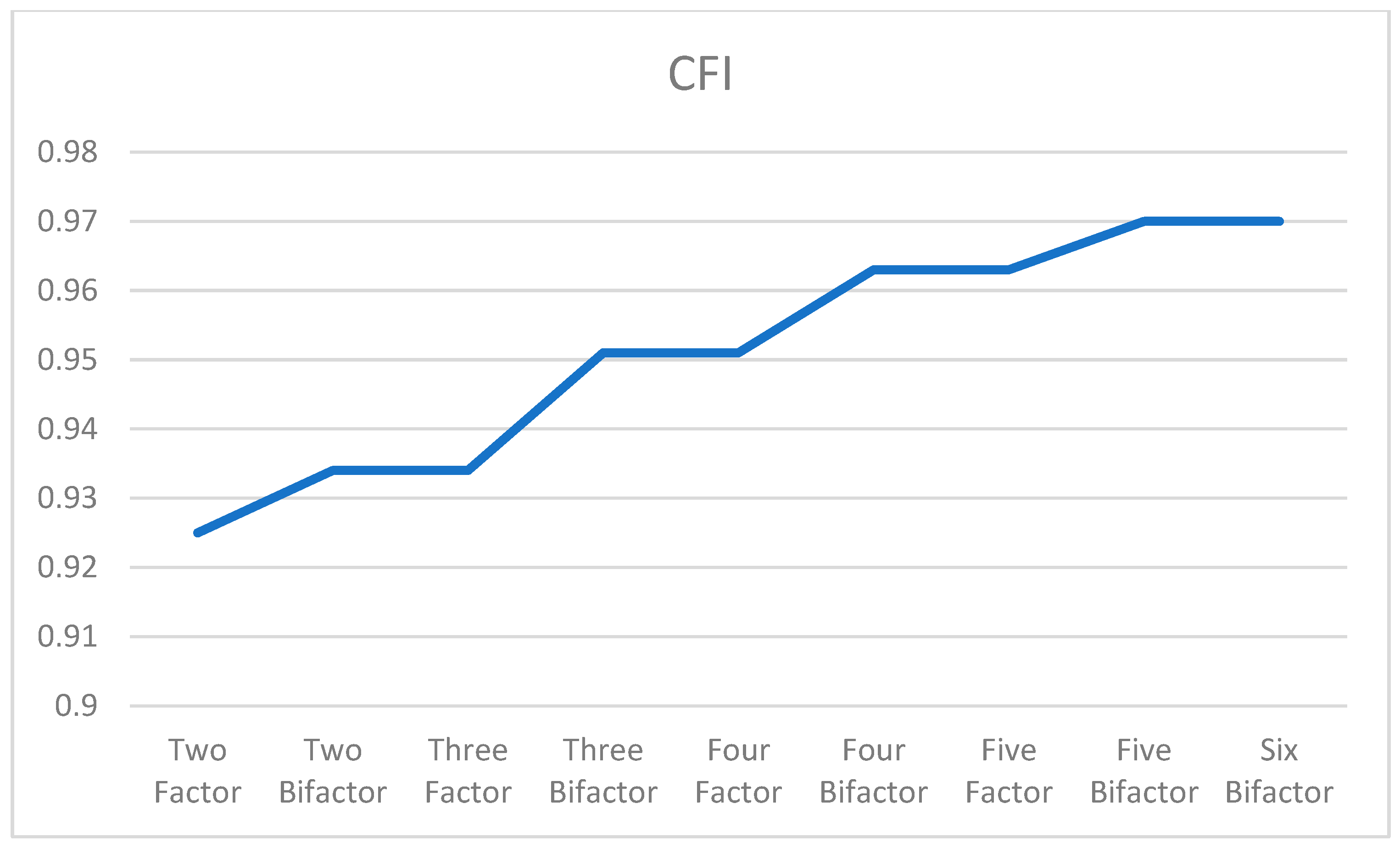

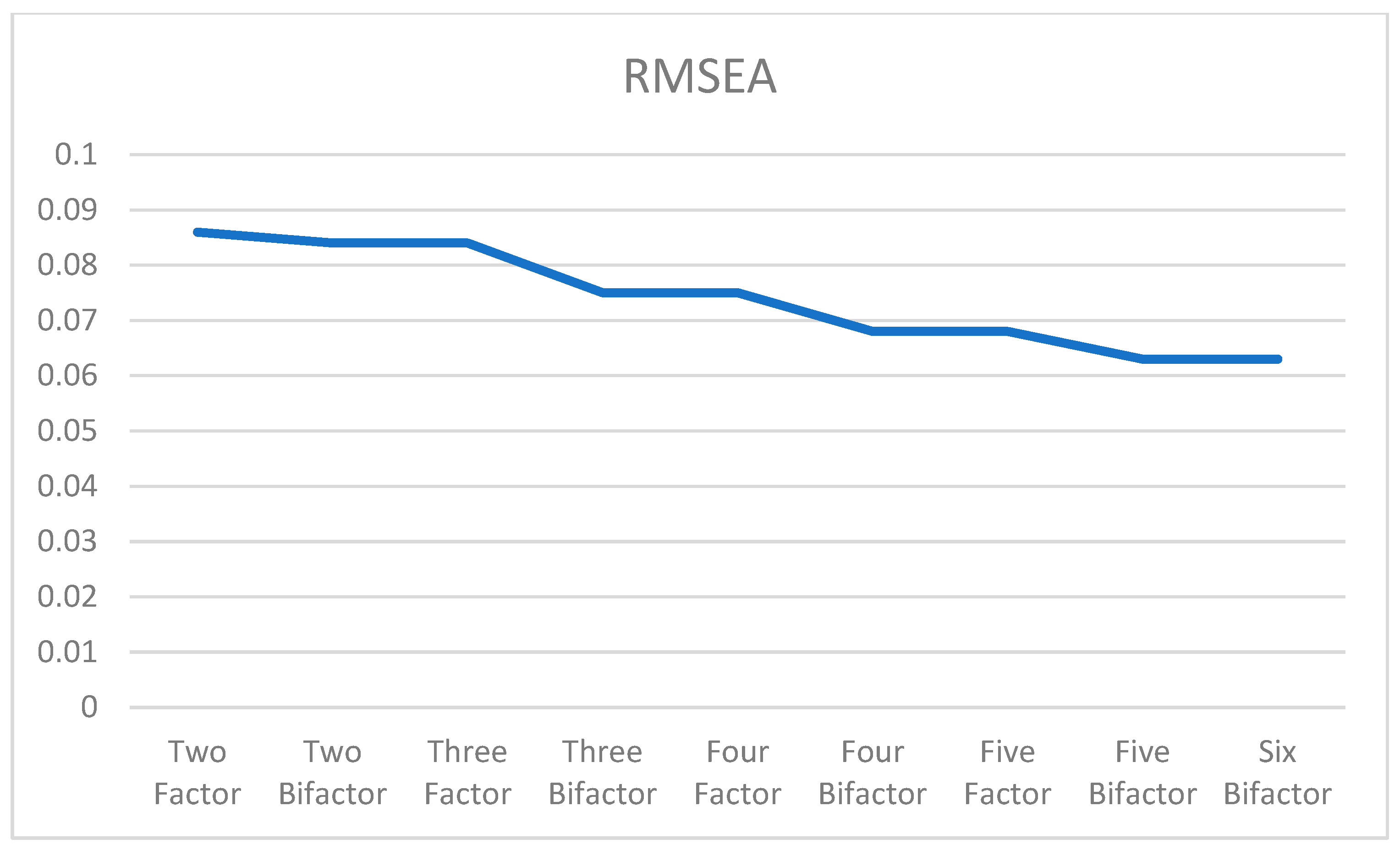

| CFA | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Factor | 0.851 | 0.841 | 0.118 | 0.108 |

| Three Factors | 0.863 | 0.854 | 0.113 | 0.105 |

| Three Bifactors | 0.929 | 0.919 | 0.084 | 0.069 |

| ESEM | ||||

| Two Factors | 0.925 | 0.915 | 0.086 | 0.07 |

| Two Bifactors | 0.934 | 0.919 | 0.084 | 0.06 |

| Three Factors | 0.934 | 0.919 | 0.084 | 0.06 |

| Three Bifactors | 0.951 | 0.936 | 0.075 | 0.051 |

| Four Factors | 0.951 | 0.936 | 0.075 | 0.051 |

| Four Bifactors | 0.963 | 0.948 | 0.068 | 0.046 |

| Five Factors | 0.963 | 0.948 | 0.068 | 0.046 |

| Five Bifactors | 0.97 | 0.954 | 0.063 | 0.04 |

| Six Bifactors | 0.97 | 0.954 | 0.063 | 0.04 |

| CFA Models | Factors | Items | Average Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 bifactors with original three subscales | G | 34 | 0.64 |

| Family | 12 | −0.14 | |

| Service | 12 | −0.09 | |

| Community | 12 | 0.34 | |

| ESEM Bifactor Models | Factors | Items | Average Factor Loadings |

| 2 bifactors | G | 30 items; 4–7, 9–14, 15–34 | 0.69 |

| F1 | 4 items; 5, 7, 10, 11 | 0.5 | |

| F2 | 8 items; 8, 14, 15, 20, 22, 24, 26 | 0.55 | |

| 3 bifactors | G | 30 items; 4–7, 9–34 | 0.68 |

| F1 | 7 items; 8, 10, 14, 15, 20, 22, 24 | 0.58 | |

| F2 | 3 items; 5, 7, 11 | 0.49 | |

| F3 | 2 items; 12, 14 | 0.45 | |

| 4 bifactors | G | 33 items; 1–7, 9–34 | 0.64 |

| F1 | 2 items; 5–7 | 0.5 | |

| F2 | 8 items; 5, 8, 10, 14, 15, 20, 22, 26 | 0.56 | |

| F3 | 2 items; 12, 14 | 0.45 | |

| F4 | 1 item; 27 | 0.41 | |

| 5 bifactors | G | 29 items; 4–7, 10–34 | 0.69 |

| F1 | 3 items; 5, 7, 11 | 0.48 | |

| F2 | 6 items; 8, 10, 15, 20, 22, 24 | 0.6 | |

| F3 | No items | 0 | |

| F4 | 1 item; 28 | 0.42 | |

| F5 | 1 item; 26 | −0.45 | |

| ESEM Factor Models | Factors | Items | Average Factor Loadings |

| 2 factors (34 items) | F1 | 12 items; 5, 8, 10, 11, 14, 15, 20, 22–24, 26, 30 | 0.66 |

| F2 | 22 items; 1, 4, 6–8, 12, 13, 16–19, 21, 23, 25, 27–34 | 0.6 | |

| 3 factors (36 items) | F1 | 9 items; 2, 5–7, 9–12, 14 | 0.6 |

| F2 | 17 items; 1, 4, 13, 16–19, 21, 23, 25, 27–29, 31–34 | 0.6 | |

| F3 | 10 items; 8, 10, 14, 15, 20, 22–26 | 0.61 | |

| 4 factors (35 items) | F1 | 8 items; 2, 4–7, 9–11 | 0.58 |

| F2 | 8 items; 12–14, 16–19, 21 | 0.62 | |

| F3 | 9 items 8, 10, 14, 15, 20, 22, 24–26 | 0.6 | |

| F4 | 10 items; 1, 4, 23, 27–29, 31–34 | 0.53 | |

| 5 factors (41 items) | F1 | 7 items; 2, 5–7, 9–11 | 0.58 |

| F2 | 9 items; 11–14, 16–19, 21 | 0.53 | |

| F3 | 9 items; 8, 10, 14, 15, 20, 22–24, 26 | 0.57 | |

| F4 | 7 items; 1, 3, 4, 21, 24, 32, 34 | 0.52 | |

| F5 | 9 items; 16, 17, 25–29, 31, 33 | 0.55 | |

| 6 factors (33 items) | F1 | 7 items; 2, 5–7, 9–11 | 0.55 |

| F2 | 6 items; 11–14, 18–19 | 0.58 | |

| F3 | 5 items; 8, 10, 15, 20, 22 | 0.63 | |

| F4 | 7 items; 16, 17, 27–29, 31, 33 | 0.57 | |

| F5 | 4 items; 23–26 | 0.61 | |

| F6 | 4 items; 4, 21, 32, 34 | 0.55 |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | - | ||

| F2 | 0.45 *** | - | |

| F3 | 0.403 *** | 0.248 *** | - |

| Items | Primary Factor Loadings | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Managing the Child’s Needs and Family Functioning | 2 | 0.51 |

| 5 | 0.71 | |

| 6 | 0.61 | |

| 7 | 0.79 | |

| 9 | 0.43 | |

| 11 | 0.81 | |

| 12 | 0.55 | |

| Factor 2: Parenting Confidence and Service Navigation | 1 | 0.55 |

| 4 | 0.41 | |

| 13 | 0.54 | |

| 16 | 0.57 | |

| 17 | 0.67 | |

| 18 | 0.72 | |

| 19 | 0.55 | |

| 21 | 0.62 | |

| 27 | 0.83 | |

| 28 | 0.77 | |

| 29 | 0.69 | |

| 31 | 0.60 | |

| 32 | 0.47 | |

| 33 | 0.65 | |

| 34 | 0.67 | |

| Factor 3: System-Level Advocacy and Collective Action Beyond the Individual Family | 8 | 0.70 |

| 10 | 0.54 | |

| 14 | 0.49 | |

| 15 | 0.55 | |

| 20 | 0.82 | |

| 22 | 0.88 | |

| 23 | 0.45 | |

| 24 | 0.65 | |

| 25 | 0.45 | |

| 26 | 0.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, H.; Rios, K. Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the Family Empowerment Scale Among Latinx Parents of Children with Disabilities: An Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040133

Hong H, Rios K. Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the Family Empowerment Scale Among Latinx Parents of Children with Disabilities: An Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. AppliedMath. 2025; 5(4):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040133

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Hyeri, and Kristina Rios. 2025. "Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the Family Empowerment Scale Among Latinx Parents of Children with Disabilities: An Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Analysis" AppliedMath 5, no. 4: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040133

APA StyleHong, H., & Rios, K. (2025). Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the Family Empowerment Scale Among Latinx Parents of Children with Disabilities: An Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. AppliedMath, 5(4), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040133