From Painkillers to Antidiabetics: Structural Modification of NSAID Scaffolds for Drug Repurposing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Inhibition of Diabetes Mellitus-Associated Enzymes

2.1. Inhibitory Activity of Conventional NSAIDs Against Diabetes-Associated Enzymes

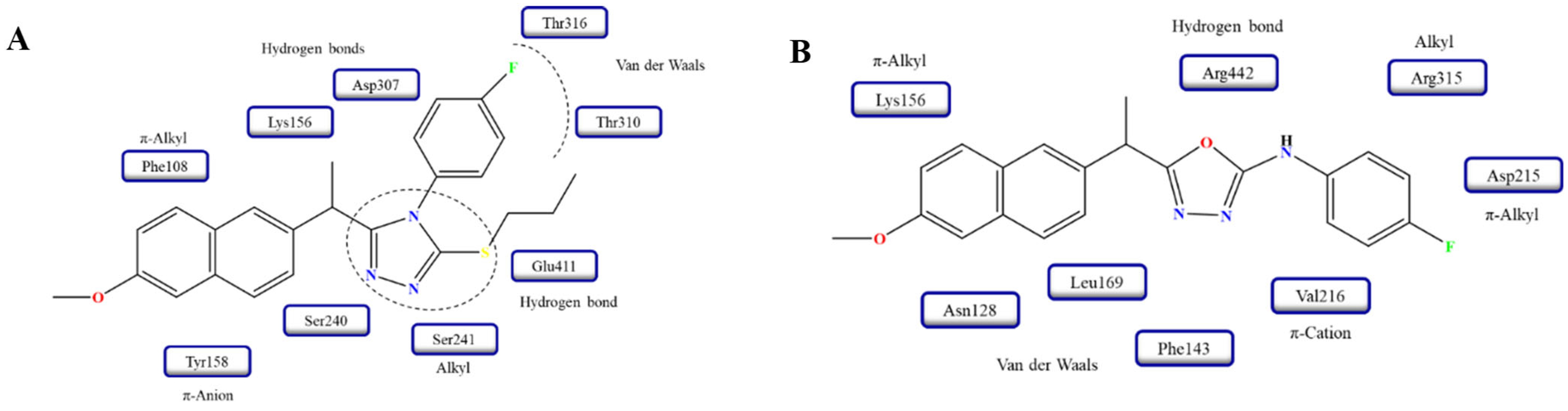

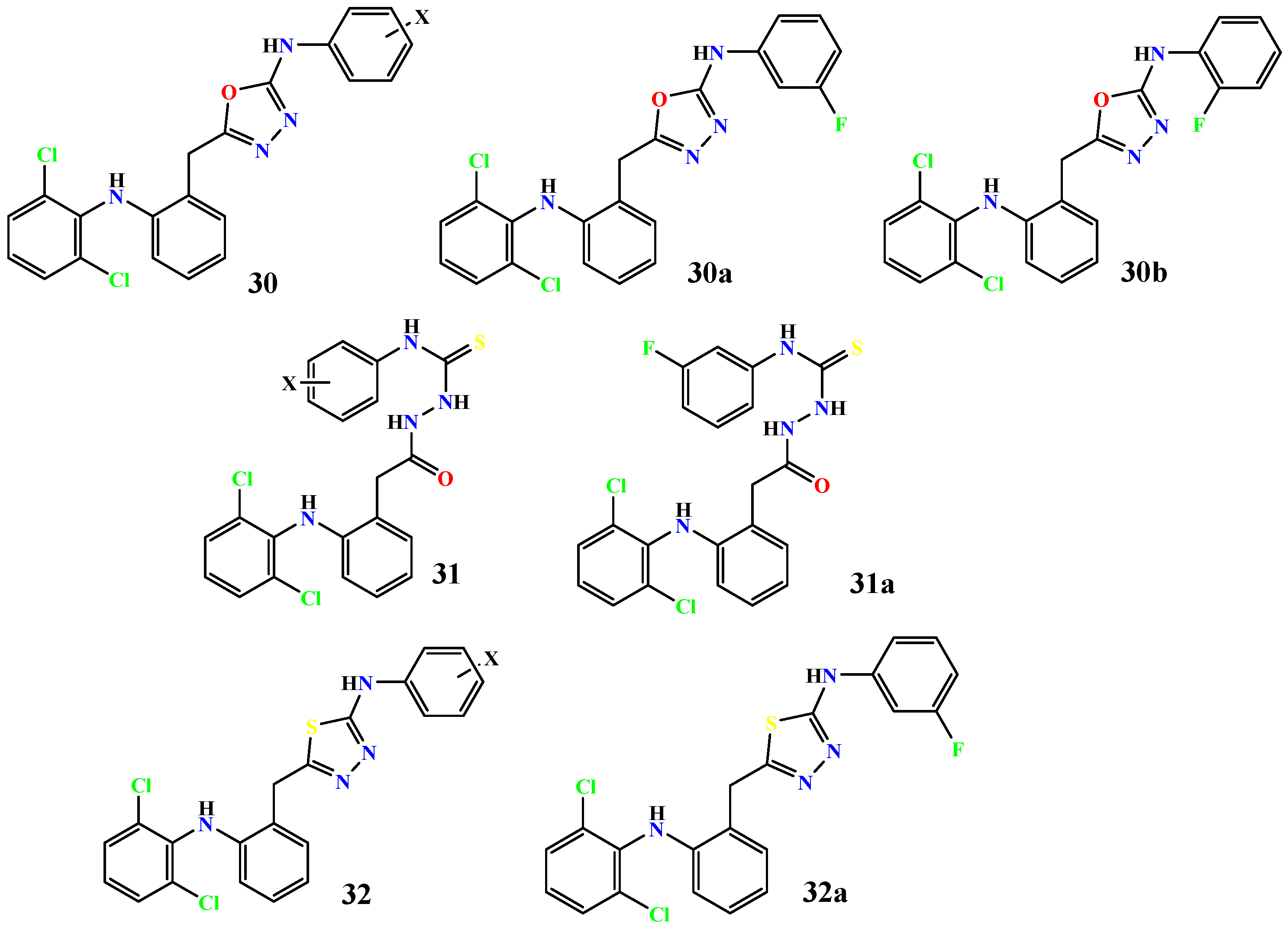

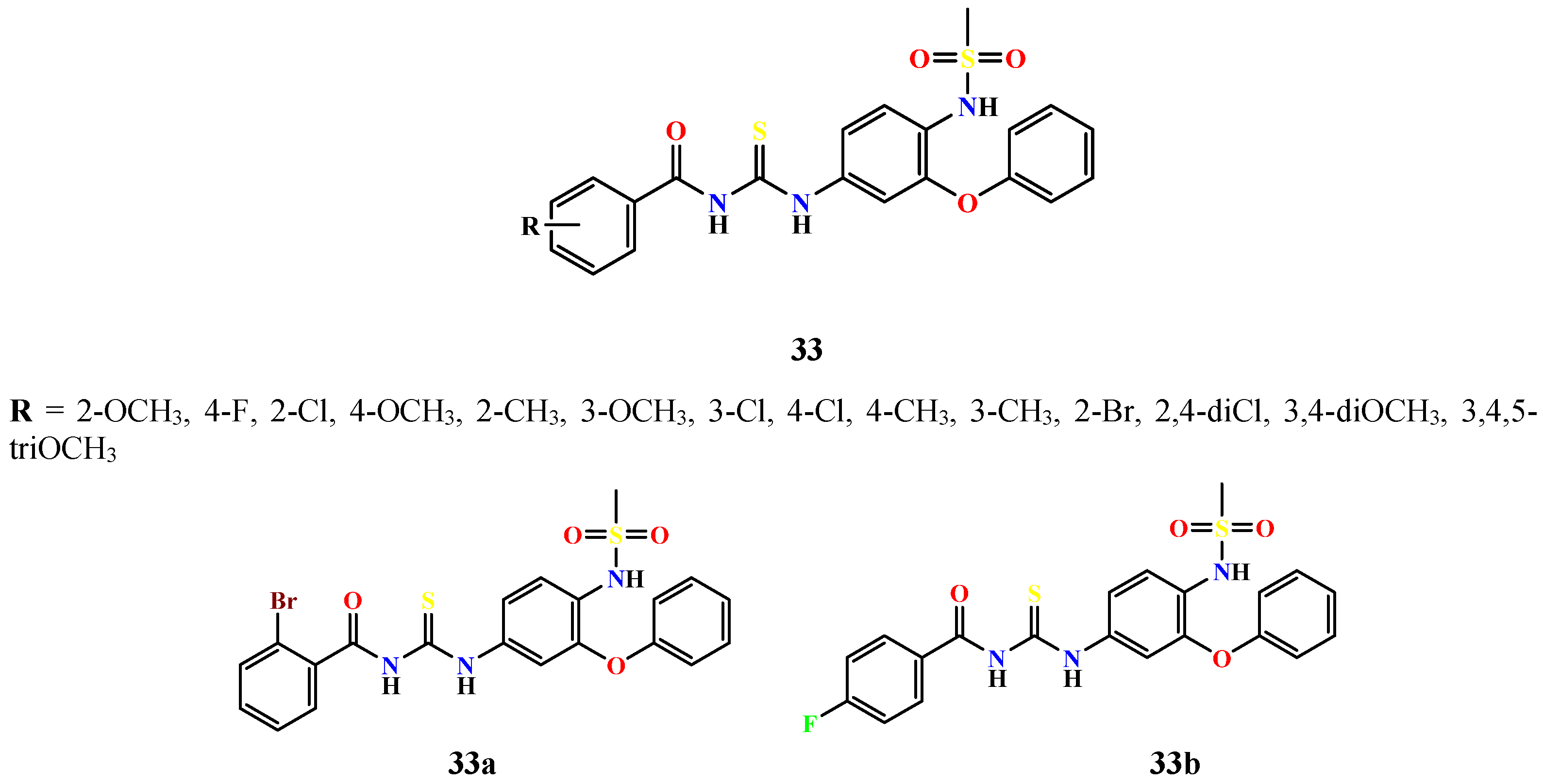

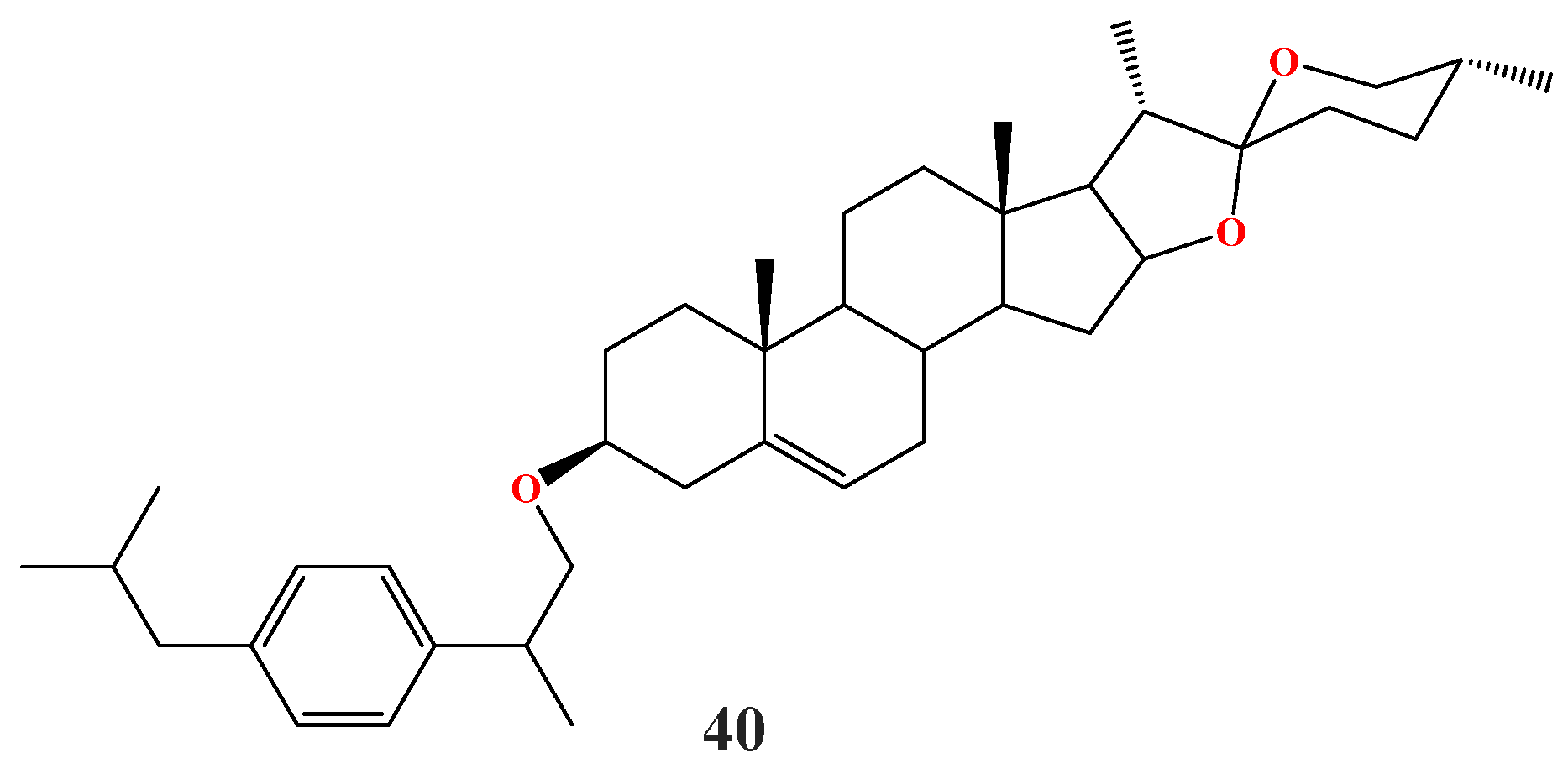

2.2. Inhibitory Activity of NSAID Derivatives Against Diabetes-Associated Enzymes

3. Inhibition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4)

4. Other Hypoglycemic Mechanisms of NSAIDs and Their Derivatives

5. Structure-Activity Relationships

6. Safety and Pharmacokinetic Profiles of NSAID Derivatives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suryasa, I.W.; Rodríguez-Gámez, M.; Koldoris, T. Health and treatment of diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Health Sci. 2021, 5, 572192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.D.; Gloyn, A.L.; Evans-Molina, C.; Joseph, J.J.; Misra, S.; Pajvani, U.B.; Simcox, J.; Susztak, K.; Drucker, D.J. Diabetes mellitus—Progress and opportunities in the evolving epidemic. Cell 2024, 187, 3789–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugandh, F.; Chandio, M.; Raveena, F.; Kumar, L.; Karishma, F.; Khuwaja, S.; Memon, U.A.; Bai, K.; Kashif, M.; Varrassi, G.; et al. Advances in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus: A Focus on Personalized Medicine. Cureus 2023, 15, e43697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruze, R.; Liu, T.; Zou, X.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Yin, X.; Xu, Q. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1161521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diabetes; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Sharaky, M.; Khattab, M.; Ashour, N.A.; Zaid, R.T.; Roh, E.J.; Elkamhawy, A.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Diabetes mellitus: Classification, mediators, and complications; a gate to identify potential targets for the development of new effective treatments. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilworth, L.; Facey, A.; Omoruyi, F. Diabetes Mellitus and Its Metabolic Complications: The Role of Adipose Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, L.; Carr, D.F.; Pirmohamed, M. Pharmacogenomics of NSAID-Induced Upper Gastrointestinal Toxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 684162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, O.; Human, M.M.; Featherstone, K. Pharmacologic therapy for acute pain. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 104, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, H.; Rodrigues, I.; Napoleão, L.; Lira, L.; Marques, D.; Veríssimo, M.; Andrade, J.P.; Dourado, M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), pain and aging: Adjusting prescription to patient features. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, S.; Mazumder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M.L.; Makowska, J.S. Seven Steps to the Diagnosis of NSAIDs Hypersensitivity: How to Apply a New Classification in Real Practice? Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2015, 7, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.İ.; Tunç, C.Ü.; Atalay, P.; Erdoğan, Ö.; Ünal, G.; Bozkurt, M.; Aydın, Ö.; Çevik, Ö.; Küçükgüzel, Ş.G. Design, synthesis, and in vitro and in vivo anticancer activity studies of new (S)-Naproxen thiosemicarbazide/1,2,4-triazole derivatives†. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 6046–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodosis-Nobelos, P.; Marc, G.; Rekka, E.A. Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of Antioxidant and NSAID Derivatives with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Plasma Lipid Lowering Effects. Molecules 2024, 29, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I.; Manolov, S.; Bojilov, D.; Marc, G.; Dimitrova, D.; Oniga, S.; Oniga, O.; Nedialkov, P.; Stoyanova, M. Novel Flurbiprofen Derivatives as Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Synthesis, In Silico, and In Vitro Biological Evaluation. Molecules 2024, 29, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguila-Muñoz, D.G.; Jiménez-Montejo, F.E.; López-López, V.E.; Mendieta-Moctezuma, A.; Rodríguez-Antolín, J.; Cornejo-Garrido, J.; Cruz-López, M.C. Evaluation of α-Glucosidase Inhibition and Antihyperglycemic Activity of Extracts Obtained from Leaves and Flowers of Rumex crispus L. Molecules 2023, 28, 5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Wang, H.; Cao, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; He, C.; Wang, M. Inhibition mechanism of α-glucosidase inhibitors screened from Tartary buckwheat and synergistic effect with acarbose. Food Chem. 2023, 420, 136102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, U.; Das, A.K.; Ghosh, S.; Sil, P.C. An overview on the role of bioactive α-glucosidase inhibitors in ameliorating diabetic complications. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 145, 111738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonemoto, R.; Shimada, M.; Gunawan-Puteri, M.D.; Kato, E.; Kawabata, J. α-Amylase Inhibitory Triterpene from Abrus precatorius Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8411–8414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Feng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W. α-Glucosidase inhibitors isolated from medicinal plants. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2014, 3, 136–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, S. Recent Advances in Synthetic α-Glucosidase Inhibitors. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, N.; Ullah, S.; Khan, M.A.; Zafar, H.; Atia-Tul-Wahab; Choudhary, M.I.; Yousuf, S. Celebrex derivatives: Synthesis, α-glucosidase inhibition, crystal structures and molecular docking studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 106, 104499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S.; Abid, O.U.; Sardar, A.; Abdullah, S.; Shahid, W.; Ashraf, M.; Ejaz, S.A.; Saeed, A.; Shah, B.A.; Niaz, B. Exploring ibuprofen derivatives as α-glucosidase and lipoxygenase inhibitors: Cytotoxicity and in silico studies. Arch. Pharm. 2022, 355, e2200013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthy, N.S.; Ramos, M.J.; Fernandes, P.A. Studies on α-glucosidase inhibitors development: Magic molecules for the treatment of carbohydrate mediated diseases. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, R.T. On the Treatment of Glycosuria and Diabetes Mellitus with Sodium Salicylate. Br. Med. J. 1901, 1, 760–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Konstantopoulos, N.; Lee, J.; Hansen, L.; Li, Z.W.; Karin, M.; Shoelson, S.E. Reversal of Obesity- and Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance with Salicylates or Targeted Disruption of Ikkβ. Science 2001, 293, 1673–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundal, R.S.; Petersen, K.F.; Mayerson, A.B.; Randhawa, P.S.; Inzucchi, S.; Shoelson, S.E.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanism by which high-dose aspirin improves glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Ye, B.; Ju, W.; Orser, B.; Fox, J.E.; Wheeler, M.B.; Wang, Q.; Lu, W.Y. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase insulin release from beta cells by inhibiting ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 151, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.P. The COX-2/PGE2/EP3/Gi/o/cAMP/GSIS Pathway in the Islet: The Beat Goes On. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1464–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Dandapani, M.; Hardie, D.G. AMPK: Mediating the metabolic effects of salicylate-based drugs? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 24, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, S.A.; Fullerton, M.D.; Ross, F.A.; Schertzer, J.D.; Chevtzoff, C.; Walker, K.J.; Peggie, M.W.; Zibrova, D.; Green, K.A.; Mustard, K.J.; et al. The Ancient Drug Salicylate Directly Activates AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Science 2012, 336, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.S.; Russe, O.Q.; Möser, C.V.; Ferreirós, N.; Kynast, K.L.; Knothe, C.; Olbrich, K.; Geisslinger, G.; Niederberger, E. AMP-activated protein kinase is activated by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 762, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoelson, S.E.; Lee, J.; Yuan, M. Inflammation and the IKKβ/IκB/NF-κB axis in obesity- and diet-induced insulin resistance. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2003, 27, S49–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J. Effects of anti-inflammatory therapies on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1125116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Zhang, Y.J.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y. Celecoxib Ameliorates Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis in Type 2 Diabetic Rats via Suppression of the Non-Canonical Wnt Signaling Pathway Expression. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e83819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanselman, E.C.; Harmon, C.P.; Deng, D.; Sywanycz, S.M.; Caronia, L.; Jiang, P.; Breslin, P.A.S. Ibuprofen inhibits human sweet taste and glucose detection implicating an additional mechanism of metabolic disease risk reduction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 2682–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaduševičius, E. Novel Applications of NSAIDs: Insight and Future Perspectives in Cardiovascular, Neurodegenerative, Diabetes and Cancer Disease Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, M.Y.; Shoelson, S.E. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Lu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Pan, X. A Review on the in vitro and in vivo screening of α-glucosidase Inhibitors. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Xie, T.; Wu, Q.; Hu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Luo, F. Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitory Peptides: Sources, Preparations, Identifications, and Action Mechanisms. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, N.; Sharma, M.; Singh, S.; Goyal, A. Recent Advances of α-Glucosidase Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 2069–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestri, F.; Moschini, R.; Mura, U.; Cappiello, M.; Del Corso, A. In Search of Differential Inhibitors of Aldose Reductase. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kapoor, A.; Bhatnagar, A. Physiological and Pathological Roles of Aldose Reductase. Metabolites 2021, 11, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukami, H.; Osonoi, S. Pathogenesis and Molecular Treatment Strategies of Diabetic Neuropathy: Collateral Glucose-Utilizing Pathways in Diabetic Polyneuropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathebula, S.D. Polyol pathway: A possible mechanism of diabetes complications in the eye. Afr. Vis. Eye Health 2015, 74, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Kumar, V.; Nayak, S.K.; Wadhwa, P.; Kaur, P.; Sahu, S.K. Alpha-amylase as molecular target for treatment of diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive review. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 98, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Goyal, K.; Mehan, S.; Singh, G. Dual α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors: Recent progress from natural and synthetic resources. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 163, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, N. A review of α-amylase inhibitors on weight loss and glycemic control in pathological state such as obesity and diabetes. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2016, 25, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boztaş, F.Y.; Tunalı, S. In vitro Inhibitory Effects of Some Antiviral, Antidiabetic, and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Active Compounds on α-Glucosidase and Myeloperoxidase Activities. J. Turk. Chem. Soc. Sect. A Chem. 2024, 11, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Y.; Duran, H.E.; Durmaz, L.; Taslimi, P.; Beydemir, Ş.; Gulçin, İ. The Influence of Some Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs on Metabolic Enzymes of Aldose Reductase, Sorbitol Dehydrogenase, and α-Glycosidase: A Perspective for Metabolic Disorders. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 190, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, R.; Satpute, B.; Patil, R.; Kumar, D.; Suryawanshi, M.; Patil, T.; Pawar, A.; Gawade, B.; Sakat, S. Synthesis and molecular docking of novel biguanide-NSAIDs hybrid with dual anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1320, 139512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, W.; Chen, H.; Bian, X.; Yang, G. A New Series of Salicylic Acid Derivatives as Non-Saccharide α-Glucosidase Inhibitors and Antioxidants. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 42, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S.; Abid, O.U.R.; Sardar, A.; Shah, B.A.; Rafiq, M.; Wadood, A.; Ghufran, M.; Rehman, W.; Zain-ul-Wahab; Iftikhar, F.; et al. Design, synthesis, in vitro evaluation, and docking studies on ibuprofen-derived 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives as dual α-glucosidase and urease inhibitors. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S.; Saadullah, M.; Fakhar-e-Alam, M.; Carradori, S.; Sardar, A.; Niaz, B.; Atif, M.; Zara, S.; Rashad, M. Isatin-based ibuprofen and mefenamic acid Schiff base derivatives as dual inhibitors against urease and α-glucosidase: In vitro, in silico and cytotoxicity studies. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2024, 28, 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Zainab; Elhenawy, A.A.; Ur Rehman, M.; Shahidul Islam, M.; Dahlous, K.A.; Talab, F.; Syed; Shah, A.A.; Ali, M.; et al. Synthesis of Flurbiprofen-Based Amide Derivatives as Potential Leads for Diabetic Management: In Vitro α-Glucosidase Inhibition, Molecular Docking and DFT Simulation Approach. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Alam, A.; Khan, K.M.; Salar, U.; Chigurupati, S.; Wadood, A.; Ali, F.; Mohammad, J.I.; Riaz, M.; Perveen, S. Flurbiprofen derivatives as novel α-amylase inhibitors: Biology-oriented drug synthesis (BIODS), in vitro, and in silico evaluation. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 81, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Ali, M.; Rehman, N.U.; Ullah, S.; Halim, S.A.; Latif, A.; Zainab; Khan, A.; Ullah, O.; Ahmad, S.; et al. Bio-Oriented Synthesis of Novel (S)-Flurbiprofen Clubbed Hydrazone Schiff’s Bases for Diabetic Management: In Vitro and In Silico Studies. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardar, A.; Abid, O.U.R.; Daud, S.; Fakhar-e-Alam, M.; Siddique, M.H.; Ashraf, M.; Shahid, W.; Ejaz, S.A.; Atif, M.; Ahmad, S.; et al. Design, synthesis, in vitro and in silico studies of naproxen derivatives as dual lipoxygenase and α-glucosidase inhibitors. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2022, 26, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, A.; Abid, O.U.R.; Khan, S.; Hussain, R.; Dawood, S.; Rehman, W.; Aziz, T.; Shah, B.; Alharbi, M.; Alasmari, A. Identification of in vitro α-glucosidase and urease inhibitory effect, and in silico studies of naproxen-derived 1,3,4-oxadiazole-based Schiff-base derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1305, 137712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S.; Abid, O.U.R.; Rehman, W.; Sardar, A.; Alanazi, M.M.; Rasheed, L.; Ejaz, S.A.; Fayyaz, A.; Shah, B.; Maalik, A. Exploring the potential of new mefenamic acid derivatives as α-glucosidase inhibitors: Structure-activity relationship, in vitro and in silico studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1316, 138812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamle, N.J.; Tella, A.C.; Obaleye, J.A.; Balogun, F.O.; Ashafa, A.O.; Ajibade, P.A. Synthesis, characterization, antioxidant and antidiabetic studies of Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes of tolfenamic acid/mefenamic acid with 1-methylimidazole. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 513, 119942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, A.; Abid, O.U.; Rehman, W.; Rasheed, L.; Alanazi, M.M.; Daud, S.; Rafiq, M.; Wadood, A.; Shakeel, M. Synthesis and biological evaluation of diclofenac acid derivatives as potential lipoxygenase and α-glucosidase inhibitors. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 240543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Shafique, I.; Saeed, A.; Shabir, G.; Saleem, A.; Taslimi, P.; Taskin Tok, T.; Kirici, M.; Üç, E.M.; Hashmi, M.Z. Nimesulide linked acyl thioureas potent carbonic anhydrase I, II and α-glucosidase inhibitors: Design, synthesis and molecular docking studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2022, 6, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaly, W.A.A.; Elshewy, A.; Nemr, M.T.M.; Abdou, K.; Sayed, A.M.; Kahk, N.M. Discovery of novel thiazole derivatives containing pyrazole scaffold as PPAR-γ Agonists, α-Glucosidase, α-Amylase and COX-2 inhibitors; Design, synthesis and in silico study. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 152, 107760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahim, K.; Shan, M.; Ul Haq, I.; Nawaz, M.N.; Maryam, S.; Alturki, M.S.; Al Khzem, A.H.; Metwally, K.; Cavalu, S.; Alqifari, S.F.; et al. Revolutionizing Treatment Strategies for Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disorders: The Impact of Dipeptidyl-Peptidase 4 Inhibitors. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 1897–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capuano, A.; Sportiello, L.; Maiorino, M.I.; Rossi, F.; Giugliano, D.; Esposito, K. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes therapy: Focus on alogliptin. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2013, 7, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, V.; Alam, O.; Siddiqui, N.; Jha, M.; Manaithiya, A.; Bawa, S.; Sharma, N.; Alshehri, S.; Alam, P.; Shakeel, F. Insight into Structure Activity Relationship of DPP-4 Inhibitors for Development of Antidiabetic Agents. Molecules 2023, 28, 5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittepu, V.C.S.R.; Kalhotra, P.; Osorio-Gallardo, T.; Gallardo-Velázquez, T.; Osorio-Revilla, G. Repurposing of FDA-Approved NSAIDs for DPP-4 Inhibition as an Alternative for Diabetes Mellitus Treatment: Computational and in Vitro Study. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; He, Y.; Zhu, G.; Cui, X.; Tang, L. Design, synthesis and insulin-sensitizing activity of indomethacin and diclofenac derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 3324–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.Q.; Cui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.F.; Tang, L. Diclofenac derivatives with insulin-sensitizing activity. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2011, 22, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, S.; Mahendiran, D.; Senthil Kumar, R.; Kalilur Rahiman, A. In Vitro Antioxidant and Insulin Mimetic Activities of Heteroleptic Oxovanadium(IV) Complexes with Thiosemicarbazones and Naproxen. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 6245–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, G.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Huang, B.; Du, D.; He, S.; Zhang, R.; Xing, Z.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Q.; et al. Synthesis of Diosgenin-Ibuprofen Derivatives and Their Activities against Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navas, A.; Jannus, F.; Fernández, B.; Cepeda, J.; Medina O’Donnell, M.; Díaz-Ruiz, L.; Sánchez-González, C.; Llopis, J.; Seco, J.M.; Rufino-Palomares, E.; et al. Designing Single-Molecule Magnets as Drugs with Dual Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Diabetic Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.S.; Das, N.; Al Mahmud, Z.; Rahman, S.M.A. Pharmacological Evaluation of Naproxen Metal Complexes on Antinociceptive, Anxiolytic, CNS Depressant, and Hypoglycemic Properties. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 2016, 3040724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Enzyme | IC50 (μM) | Standard, IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-Glucosidase | 52,300.00 | Acarbose 10,570.00 | [49] |

| 2 | 73,190.00 | |||

| 3 | / | |||

| 4 | 22,560.00 | |||

| 5 | 4020.00 | |||

| 6 | 206,230.00 | |||

| 7 | α-Glucosidase SDH AR | 103.63 / 18.89 | / | [50] |

| 8 | α-Glucosidase SDH AR | 408.61 0.013 783.00 | ||

| 9 | α-Glucosidase SDH AR | 87.35 14.00 7870.00 | ||

| 10 | α-Glucosidase SDH AR | 8.18 0.010 1.29 |

| Compound | Enzyme | IC50 (μM) | Standard, IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11a | α-Glucosidase α-Amylase | 600.39 215.03 | Acarbose 20.29 110.87 | [51] |

| 11b | 472.05 231.68 | |||

| 11c | 594.98 239.30 | |||

| 11d | 1191.07 371.75 | |||

| 11e | 814.03 372.62 | |||

| 11f | 1164.06 539.61 | |||

| 11g | 804.97 327.72 | |||

| 11h | 749.20 408.54 | |||

| 12a | α-Glucosidase | 86.00 | Acarbose 450.00 | [52] |

| 12b | 150.00 | |||

| 12c | 320.00 |

| Compound | Enzyme | IC50 (μM) | Standard, IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13a | α-Glucosidase | 3.05 | Acarbose 375.82 | [23] |

| 13b | 3.12 | |||

| 14a | 16.01 | [53] | ||

| 14b | 39.06 | |||

| 15a | 28.2 | [54] |

| Compound | Enzyme | IC50 (μM) | Standard, IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16a | α-Glucosidase | 5.98 | Acarbose 875.75 | [55] |

| 16b | 8.19 | |||

| 16c | 10.11 | |||

| 16d | 5.67 | |||

| 16e | 17.87 | |||

| 16f | 12.89 | |||

| 16h | 16.78 | |||

| 17a | α-Amylase | 1.69 | Acarbose 0.9 | [56] |

| 17b | 1.04 | |||

| 17c | 1.25 | |||

| 18a | 1.6 | |||

| 19a | α-Glucosidase | 0.93 | Acarbose 875.75 | [57] |

| 19b | 1.52 | |||

| 19c | 3.41 | |||

| 19d | 4.77 | |||

| 19e | 7.16 | |||

| 19f | 10.26 |

| Compound | Enzyme | IC50 (μM) | Standard, IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20a | α-Glucosidase | 1.01 | Acarbose 375.82 | [58] |

| 21a | 1.10 | |||

| 22a | 6.14 | [59] | ||

| 22b | 9.90 | |||

| 22c | 25.90 | |||

| 22d | 34.23 | |||

| 22e | 38.07 |

| Compound | Enzyme | IC50 (μM) | Standard, IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23a | α-Glucosidase | 9.70 | Acarbose 375.82 | [60] |

| 24a | 38.8 | |||

| 24b | 54.2 | |||

| 25a | 54.4 | |||

| 26a | 39.3 | [54] | ||

| 27 | α-Glucosidase α-Amylase | 2853.54 896.62 | Acarbose 1089.86 3318.16 | [61] |

| 28 | 6934.49 847.79 | |||

| 29 | 1700.98 944.48 |

| Compound | Enzyme | IC50 (μM) | Standard, IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30a | α-Glucosidase | 3.0 | Acarbose 376 | [62] |

| 30b | 5.0 | |||

| 31a | 7.0 | |||

| 32a | 11.0 | |||

| 33a | α-Glucosidase α-Amylase | 0.01017 0.02921 | Acarbose 22.8 10.0 | [63] |

| 33b | 0.01547 0.01245 | |||

| 34a | α-Glucosidase | 92.32 | Acarbose 875.75 | [22] |

| 35a | α-Glucosidase α-Amylase | 0.158 32.46 | Acarbose 0.161 31.46 | [64] |

| 35b | 0.314 23.21 | |||

| 35c | 0.305 7.74 | |||

| 35d | 0.128 35.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gogić, A.; Nikolić, M.; Nedeljković, N.; Zdravković, N.; Vesović, M.; Živanović, A. From Painkillers to Antidiabetics: Structural Modification of NSAID Scaffolds for Drug Repurposing. Future Pharmacol. 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/futurepharmacol6010002

Gogić A, Nikolić M, Nedeljković N, Zdravković N, Vesović M, Živanović A. From Painkillers to Antidiabetics: Structural Modification of NSAID Scaffolds for Drug Repurposing. Future Pharmacology. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/futurepharmacol6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGogić, Anđela, Miloš Nikolić, Nikola Nedeljković, Nebojša Zdravković, Marina Vesović, and Ana Živanović. 2026. "From Painkillers to Antidiabetics: Structural Modification of NSAID Scaffolds for Drug Repurposing" Future Pharmacology 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/futurepharmacol6010002

APA StyleGogić, A., Nikolić, M., Nedeljković, N., Zdravković, N., Vesović, M., & Živanović, A. (2026). From Painkillers to Antidiabetics: Structural Modification of NSAID Scaffolds for Drug Repurposing. Future Pharmacology, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/futurepharmacol6010002