Organoids as a Revolutionary Data Source for Pharmacokinetic Modeling: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Approaches to PK Modeling

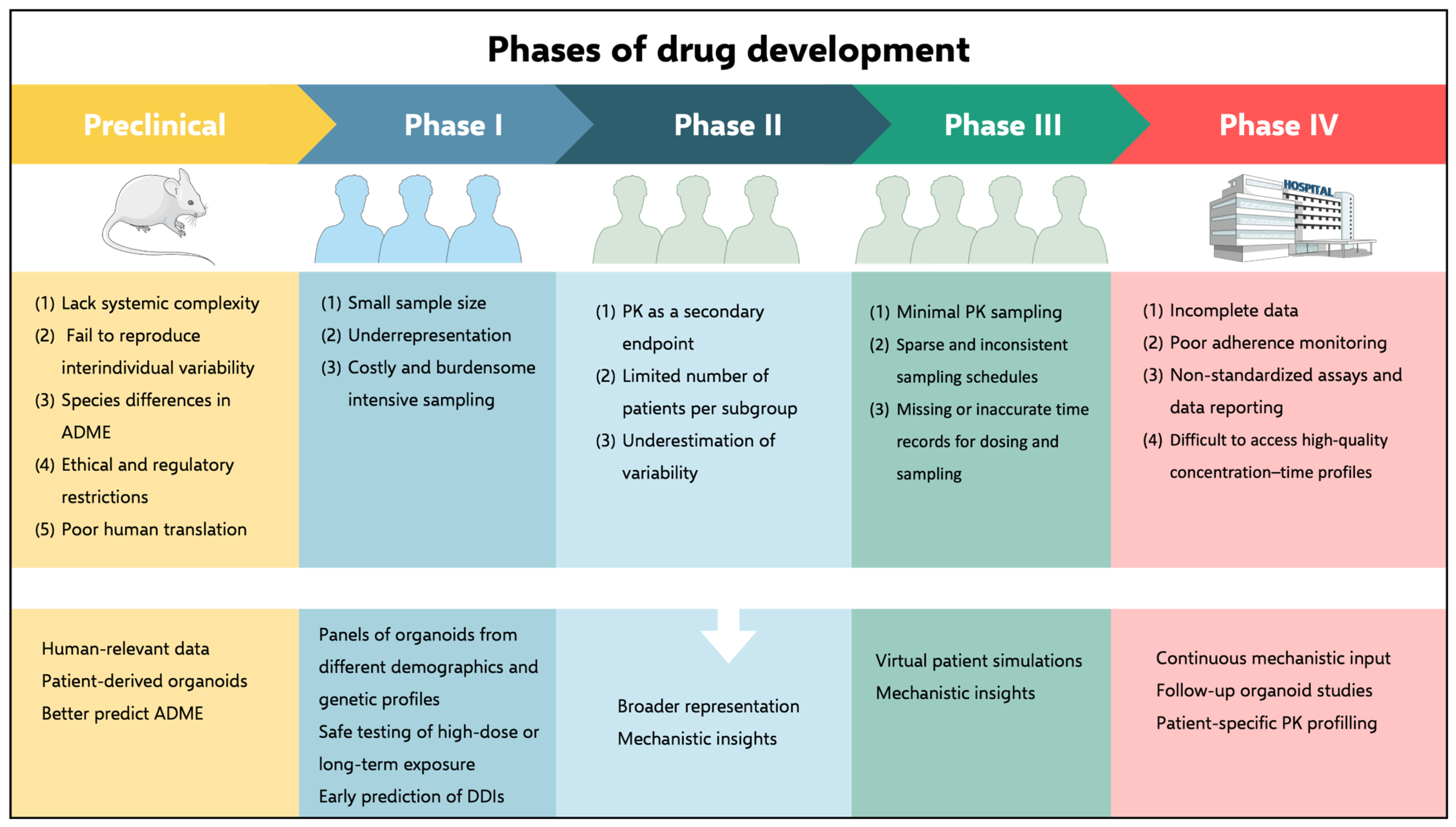

3. Clinical Studies as the Principal Data Source for PK Models

3.1. Underrepresentation in Clinical Trials

Strategies to Enhance Diversity in Clinical Trials

3.2. Data Quality Challenges: Incompleteness, Inaccuracy, and Inconsistency

3.3. Bridging Clinical Data and Computational Modeling

4. Animal Models for PK Data Generation

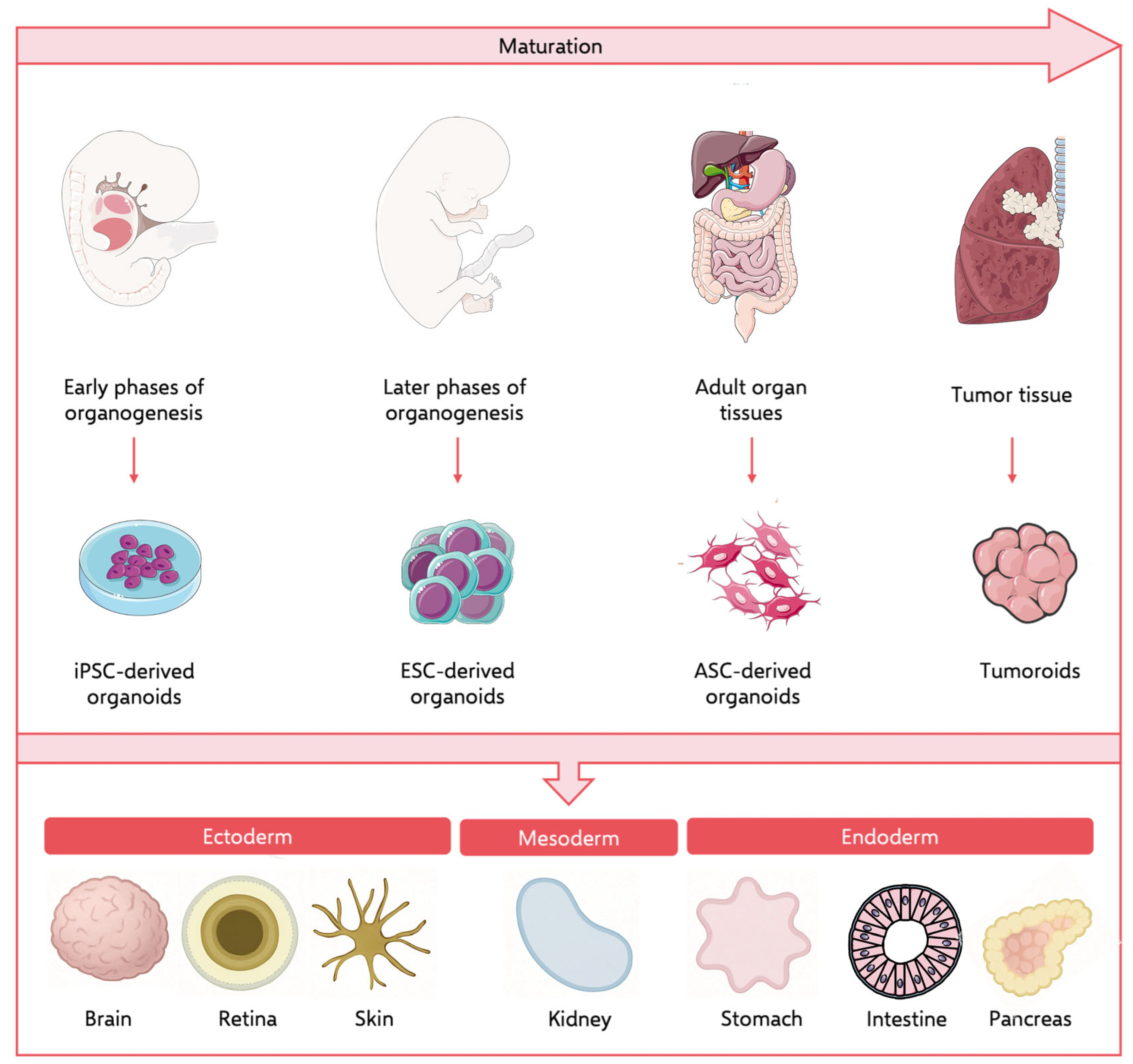

5. Organoids as an Alternative or Complementary Data Source

5.1. iPSC-Derived Organoids

5.2. Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs)

5.2.1. Intestinal Organoids

5.2.2. Liver Organoids

5.2.3. Kidney Organoids

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| ADME | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion |

| MIID | Model-informed Drug Development |

| popPK | Population Pharmacokinetic |

| PBPK | Physiologically based Pharmacokinetic |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| MBDD | Model-based Drug Development |

| NDA | New Drug Application |

| BLA | Biological License Application |

| CDER | Center for Drug Evaluation and Research |

| IIV | Interindividual Variability |

| pKa | Ionization Constant |

| DDI | Drug–drug Interaction |

| NCA | Non-compartmental Analysis |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| ADR | Adverse Drug Reaction |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| PD | Pharmacodynamics |

| DBS | Dried Blood Spots |

| ME | Measurement Error |

| GSK | GlaxoSmithKline |

| IRP | Independent Review Panel |

| CSDR | Clinical Study Data Request |

| BioLINCC | Biological Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center |

| SOAR-BMS | Supporting Open Access to Researcher-Bristol Myers Squibb |

| YODA | Yale Open Data Access |

| NHLBI | National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| DSP | Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| DCRI | Duke Clinical Research Institute |

| MRCT | Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard |

| UCSF | University of California San Francisco |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| PwHA | People with Hemophilia A |

| LASCA | Long-acting Subcutaneous Antipsychotic |

| NSCLC | Non-small Cell Lung Cancer |

| DPNP | Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain |

| CLBP | Chronic Low Back Pain |

| PK-DB | Open Database for Pharmacokinetics Information |

| ICG | Indocyanine Green |

| DXM | Dextromethorphan |

| CYP2D6 | Cytochrome P450 2D6 |

| PubMed | Openly accessible, free database |

| CYP2E1 | Cytochrome P450 2E1 |

| CYP1A | Cytochrome P540 1A |

| CYP2C | Cytochrome P450 2C |

| CYP2D | Cytochrome P450 2D |

| CYP3A | Cytochrome P450 3A |

| GI | Gastrointestinal tract |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| ASC | Adult Stem Cell |

| MPS | Microphysiological systems |

| Caco-2 | Immortalized cell line of human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells |

| iPSC | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| PDO | Patient-derived Organoid |

| ESC | Embryonic Stem Cell |

| hiPSC | Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| Wnt | Wnt Signaling Pathway |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| RA | Retinoic Acid |

| TGFβ | Transforming Growth Factor β |

| BMP | Bone Morphogenetic Protein |

| hiPSC-IEC | hiPSC-derived Intestinal Epithelial Cell |

| CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450 3A4 |

| P-gp | P-Glycoprotein |

| ka | Absorption Rate Constant |

| kaapp | Apparent Absorption Rate Constant |

| Fa | Fraction Absorbed |

| Fg | Fraction escaping gut-wall elimination |

| HLC | Hepatocyte-like Cell |

| PHH | Primary Human Hepatocyte |

| PHH-iPS-HLC | Primary Human Hepatocyte-derived iPS-HLC |

| PDTO | Patient-derived Tumor Organoid |

| Lgr5 | Leucine-rich Repeat-containing G-protein Coupled Receptor 5 |

| FGF4 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 4 |

| Sag | S-arrestin gene |

| BMP4 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 |

| FGF7 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 7 |

| FGF10 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 10 |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor |

| Y-27632 | ROCK Inhibitor |

| ENR | Enoyl-acyl Carrier Protein |

| MEKi | Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Inhibitor |

| BMP2 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 |

| ABCB1/MDR1 | Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette subfamily B member 1/multidrug resistance protein 1 |

| ABCG2 | Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 |

| HTS | High-throughput screening |

| DILI | Drug-Induced Liver Injury |

| NSAID | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug |

| MDCK | Madin-Darby Canine Kidney |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

References

- International Council for Harmonisation. ICH E7 Studies in Support of Special Populations: Geriatrics—Scientific Guideline; International Council for Harmonisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry Population Pharmacokinetics; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 301–827.

- European Medicines Agency. Evaluation of the Pharmacokinetics of Medicinal Products in Patients with Decreased Renal Function—Scientific Guideline; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004.

- Food and Drugs Administration. Challenge and Opportunity on the Critical Path to New Medical Products; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Dunn, A.; Gobburu, J.V.S. The Trajectory of Pharmacometrics to Support Drug Licensing and Labelling. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 91, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, F.; Läer, S. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling: Methodology, Applications, and Limitations with a Focus on Its Role in Pediatric Drug Development. Biomed. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 907461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ouyang, D. Opportunities and Challenges of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling in Drug Delivery. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 2100–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.; Rowland-Yeo, K. Basic Concepts in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling in Drug Discovery and Development. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2013, 2, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shebley, M.; Sandhu, P.; Emami Riedmaier, A.; Jamei, M.; Narayanan, R.; Patel, A.; Peters, S.A.; Reddy, V.P.; Zheng, M.; de Zwart, L.; et al. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model Qualification and Reporting Procedures for Regulatory Submissions: A Consortium Perspective. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 104, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamei, M. Recent Advances in Development and Application of Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Models: A Transition from Academic Curiosity to Regulatory Acceptance. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2016, 2, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mould, D.; Upton, R. Basic Concepts in Population Modeling, Simulation, and Model-Based Drug Development—Part 2: Introduction to Pharmacokinetic Modeling Methods. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2013, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, D.; Upton, R. Basic Concepts in Population Modeling, Simulation, and Model-Based Drug Development. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2012, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivelevich, I.; Lin, S. Visualization of Sparse PK Concentration Sampling Data, Step by Step (Improvement by Improvement). In Proceedings of the PharmaSUG 2021, Virtual, 24–27 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, E.; Gouraud, H.; Naudet, F.; Gross, C.P.; Krumholz, H.M.; Ross, J.S.; Wallach, J.D. Characteristics of Available Studies and Dissemination of Research Using Major Clinical Data Sharing Platforms. Clin. Trials 2021, 18, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathe, A.G.; Brundage, R.C.; Ivaturi, V.; Cloyd, J.C.; Chamberlain, J.M.; Elm, J.J.; Silbergleit, R.; Kapur, J.; Coles, L.D. A Pharmacokinetic Simulation Study to Assess the Performance of a Sparse Blood Sampling Approach to Quantify Early Drug Exposure. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 1444–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, E.N.; Wade, J.R.; Karlsson, M.O. Comparison of Some Practical Sampling Strategies for Population Pharmacokinetic Studies. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1996, 24, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, W.; Martinez, J.-M.; Rüppel, D.; Lockwood, G. Population Pharmacokinetics in Clinical Pharmacology. In Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Methods in Clinical Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, L.M.; Furberg, C.D.; DeMets, D.L.; Reboussin, D.M.; Granger, C.B. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-18538-5. [Google Scholar]

- Masic, I.; Miokovic, M.; Muhamedagic, B. Evidence Based Medicine—New Approaches and Challenges. Acta Inform. Medica 2008, 16, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackett, D.L.; Rosenberg, W.M.C.; Gray, J.A.M.; Haynes, R.B.; Richardson, W.S. Evidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn’t. BMJ 1996, 312, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, P.B.; Rohrich, R.J.; Chung, K.C. The Levels of Evidence and Their Role in Evidence-Based Medicine. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 128, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.Y.; Papez, V.; Chang, W.H.; Mueller, S.H.; Denaxas, S.; Lai, A.G. Comparing Clinical Trial Population Representativeness to Real-World Populations: An External Validity Analysis Encompassing 43 895 Trials and 5 685 738 Individuals across 989 Unique Drugs and 286 Conditions in England. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e674–e689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel du Vaure, C.; Dechartres, A.; Battin, C.; Ravaud, P.; Boutron, I. Exclusion of Patients with Concomitant Chronic Conditions in Ongoing Randomised Controlled Trials Targeting 10 Common Chronic Conditions and Registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: A Systematic Review of Registration Details. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, C.R.T.; Izadi, S.; Fowler, S.; Philpott-Streiff, S.; Green, P.; Suls, J.; Winter, A.C.; Colditz, G.A. Multimorbidity in Randomized Controlled Trials of Behavioral Interventions: A Systematic Review. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsley, C.A.; Selby, R.; Siu, L.L. Systematic Review of Barriers to the Recruitment of Older Patients with Cancer Onto Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3112–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulman, D.M.; Sussman, J.B.; Chen, X.; Cigolle, C.T.; Blaum, C.S.; Hayward, R.A. Examining the Evidence: A Systematic Review of the Inclusion and Analysis of Older Adults in Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronish, I.M.; Fenn, K.; Cohen, L.; Hershman, D.L.; Green, P.; Jenny Lee, S.A.; Suls, J. Extent of Exclusions for Chronic Conditions in Breast Cancer Trials. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018, 2, pky059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Spall, H.G.C.; Toren, A.; Kiss, A.; Fowler, R.A. Eligibility Criteria of Randomized Controlled Trials Published in High-Impact General Medical Journals. JAMA 2007, 297, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Morales, D.R.; Guthrie, B. Exclusion Rates in Randomized Controlled Trials of Treatments for Physical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Trials 2020, 21, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.C.; DiBlasio, C.A.; Fowler, M.E.; Zhang, Y.; Kennedy, R.E. Assessment of the Generalizability of Clinical Trials of Delirium Interventions. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2015080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Sauver, J.L.; Boyd, C.M.; Grossardt, B.R.; Bobo, W.V.; Finney Rutten, L.J.; Roger, V.L.; Ebbert, J.O.; Therneau, T.M.; Yawn, B.P.; Rocca, W.A. Risk of Developing Multimorbidity across All Ages in an Historical Cohort Study: Differences by Sex and Ethnicity. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné Pefoyo, A.J.; Bronskill, S.E.; Gruneir, A.; Calzavara, A.; Thavorn, K.; Petrosyan, Y.; Maxwell, C.J.; Bai, Y.; Wodchis, W.P. The Increasing Burden and Complexity of Multimorbidity. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, A.; Edwards, D.; Harshfield, A.; Rhodes, K.; Brimicombe, J.; Payne, R.; Griffin, S. The Epidemiology of Multimorbidity in Primary Care: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 68, e245–e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Ezzati, M.; Gregg, E.W. Multimorbidity—A Defining Challenge for Health Systems. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e599–e600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, R.A.; Avery, A.J. Polypharmacy: One of the Greatest Prescribing Challenges in General Practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2011, 61, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, K.; Shirai, K.; Tang, C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hao, Y.; Dong, J.Y. Prevalence and Trends of Polypharmacy in U.S. Adults, 1999–2018. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delara, M.; Murray, L.; Jafari, B.; Bahji, A.; Goodarzi, Z.; Kirkham, J.; Chowdhury, Z.; Seitz, D.P. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Polypharmacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.E.; Spiers, G.; Kingston, A.; Todd, A.; Adamson, J.; Hanratty, B. Adverse Outcomes of Polypharmacy in Older People: Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srijithesh, P.; Husain, S. Influence of Trial Design, Heterogeneity and Regulatory Environment on the Results of Clinical Trials: An Appraisal in the Context of Recent Trials on Acute Stroke Intervention. Ann. Indian. Acad. Neurol. 2014, 17, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, L.T.; Watkins, L.; Piña, I.L.; Elmer, M.; Akinboboye, O.; Gorham, M.; Jamerson, B.; McCullough, C.; Pierre, C.; Polis, A.B.; et al. Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials: Overcoming Critical Barriers. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2019, 44, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.L.; Alsan, M.; Morris, A.A.; Halpern, S.D. Why Diverse Clinical Trial Participation Matters. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1252–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, A.; Pacanowski, M.; Bull, J.; Zhang, L. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Drug Disposition and Response: Review of Recently Approved Drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 97, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, M.; Fadiran, E.O.; Parrish, L.J.; Griffith, R.A.; Weiss, E.; Carter, C. Dialogues on Diversifying Clinical Trials: Successful Strategies for Engaging Women and Minorities in Clinical Trials. J. Women’s Health 2012, 21, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/racial-and-ethnic-diversity-in-the-united-states-2010-and-2020-census.html (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration. Collection of Race and Ethnicity Data in Clinical Trials. Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Food and Drug Administration. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations—Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs. Guidance for Industry; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Food and Drug Administration. Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials. Guidance for Industry; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER); Center for Devices and Radiologic Health (CDRH); Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE). Collection of Race and Ethnicity Data in Clinical Trials and Clinical Studies for FDA-Regulated Medical Products. Guidance for Industry; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Laughon, M.M.; Benjamin, D.K.; Capparelli, E.V.; Kearns, G.L.; Berezny, K.; Paul, I.M.; Wade, K.; Barrett, J.; Smith, P.B.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M. Innovative Clinical Trial Design for Pediatric Therapeutics. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 4, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, W.; Selen, A.; Avant, D.; Chaurasia, C.; Crescenzi, T.; Gieser, G.; Di Giacinto, J.; Huang, S.-M.; Lee, P.; Mathis, L.; et al. Improving Pediatric Dosing through Pediatric Initiatives: What We Have Learned. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. General Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Pediatric Studies of Drugs, Including Biological Products Guidance for Industry Clinical Pharmacology Revision 1 Contains Nonbinding Recommendations; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022.

- Hunt, C.M.; Westerkam, W.R.; Stave, G.M. Effect of Age and Gender on the Activity of Human Hepatic CYP3A. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinirons, M.T.; O’Mahony, M.S. Drug Metabolism and Ageing. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 57, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, K.; Crooks, J.; Duke, E.; Stevenson, I.H. Effect of Age and Sex on Human Drug Metabolism. Br. Med. J. 1971, 3, 607–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotaniemi, E.A.; Arranto, A.J.; Pelkonen, O.; Pasanen, M. Age and Cytochrome P450-Linked Drug Metabolism in Humans: An Analysis of 226 Subjects with Equal Histopathologic Conditions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 61, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, S.J.F.; Orriëns, L.B.; Zwaag, S.M.; Poel, T.; de Hoop, M.; de Wildt, S.N. External Validation of Model-Based Dosing Guidelines for Vancomycin, Gentamicin, and Tobramycin in Critically Ill Neonates and Children: A Pragmatic Two-Center Study. Pediatr. Drugs 2020, 22, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezowska, M.; Hayden, I.S.; Brandon, A.M.; Zats, A.; Patel, M.; Barnett, S.; Ogungbenro, K.; Veal, G.J.; Taylor, A.; Suthar, J. Recommended Approaches for Integration of Population Pharmacokinetic Modelling with Precision Dosing in Clinical Practice. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 91, 1064–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdwood, S.T.; Kaplan, J.; Vinks, A.A. Methodologic Progress Note: Opportunistic Sampling for Pharmacology Studies in Hospitalized Children. J. Hosp. Med. 2020, 16, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balevic, S.J.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M. Innovative Study Designs Optimizing Clinical Pharmacology Research in Infants and Children. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 58, S58–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, K.C.; Wu, D.; Kaufman, D.A.; Ward, R.M.; Benjamin, D.K.; Sullivan, J.E.; Ramey, N.; Jayaraman, B.; Hoppu, K.; Adamson, P.C.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Fluconazole in Young Infants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 4043–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehoog, M.; Schoemaker, R.; Mouton, J.; Vandenanker, J. Vancomycin Population Pharmacokinetics in Neonates. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 67, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, B. Population Pharmacokinetics of Gentamicin in Premature Newborns. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang Girdwood, S.C.; Tang, P.H.; Murphy, M.E.; Chamberlain, A.R.; Benken, L.A.; Jones, R.L.; Stoneman, E.M.; Kaplan, J.M.; Vinks, A.A. Demonstrating Feasibility of an Opportunistic Sampling Approach for Pharmacokinetic Studies of Β-Lactam Antibiotics in Critically Ill Children. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 61, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randell, R.L.; Balevic, S.J.; Greenberg, R.G.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M.; Thompson, E.J.; Venkatachalam, S.; Smith, M.J.; Bendel, C.; Bliss, J.M.; Chaaban, H.; et al. Opportunistic Dried Blood Spot Sampling Validates and Optimizes a Pediatric Population Pharmacokinetic Model of Metronidazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e01533-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, Z.L.; Poweleit, E.A.; Paice, K.; Somers, K.M.; Pavia, K.; Vinks, A.A.; Punt, N.; Mizuno, T.; Girdwood, S.T. Tutorial on Model Selection and Validation of Model Input into Precision Dosing Software for Model-informed Precision Dosing. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 1827–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irby, D.J.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Dauki, A.M.; Badawi, M.A.; Illamola, S.M.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Phelps, M.A.; Mould, D.R. Approaches to Handling Missing or “Problematic” Pharmacology Data: Pharmacokinetics. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2021, 10, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamsen, K.M.; Duffull, S.B.; Tarning, J.; Lindegardh, N.; White, N.J.; Simpson, J.A. Optimal Designs for Population Pharmacokinetic Studies of the Partner Drugs Co-Administered with Artemisinin Derivatives in Patients with Uncomplicated Falciparum Malaria. Malar. J. 2012, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foracchia, M.; Hooker, A.; Vicini, P.; Ruggeri, A. POPED, a Software for Optimal Experiment Design in Population Kinetics. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2004, 74, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.J.; Ruppert, D.; Stefanski, L.A.; Crainiceanu, C.M. Measurement Error in Nonlinear Models; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; ISBN 9781420010138. [Google Scholar]

- Santalo, O.; Baig, U.; Poulakos, M.; Brown, D. Early Vancomycin Concentrations and the Applications of a Pharmacokinetic Extrapolation Method to Recognize Sub-Therapeutic Outcomes. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Crainiceanu, C.M.; Caffo, B.S. Practical Recommendations for Population PK Studies with Sampling Time Errors. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 69, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenel, M.; Ogungbenro, K.; Duval, V.; Laveille, C.; Jochemsen, R.; Aarons, L. Optimal Blood Sampling Time Windows for Parameter Estimation Using a Population Approach: Design of a Phase II Clinical Trial. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2005, 32, 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, F.; Slattery, J.; Groves, T.; Lang, T.; Benjamini, Y.; Day, S.; Bauer, P.; Posch, M. Sharing Clinical Trial Data on Patient Level: Opportunities and Challenges. Biom. J. 2015, 57, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Study Data Request. Available online: https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Default.aspx (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Kochhar, S.; Knoppers, B.; Gamble, C.; Chant, A.; Koplan, J.; Humphreys, G.S. Clinical Trial Data Sharing: Here’s the Challenge. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.I.; Melhim, S.B.; Al-Ramadhani, H.M.; Alzubiedi, S. Bayesian Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Eltrombopag in Chronic Hepatitis C Patients. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 44, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retout, S.; Schmitt, C.; Petry, C.; Mercier, F.; Frey, N. Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis and Exploratory Exposure–Bleeding Rate Relationship of Emicizumab in Adult and Pediatric Persons with Hemophilia A. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2020, 59, 1611–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlstein, I.; Merenlender Wagner, A.; Elgart, A.; Zandvliet, A.S.; Hellmann, F.; Lin, Y.; van Maanen, E.; Plock, N.; Fauchet, F.; Singh, R. Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling of TV-46000, a Risperidone Long-Acting Subcutaneous Antipsychotic for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. Neurol. Ther. 2025, 14, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.K.; Benzekry, S.; Mochel, J.P. Optimizing First-Line Therapeutics in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Insights from Joint Modeling and Large-Scale Data Analysis. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2025, 14, 1637–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.E.; Bailey, J.; van der Walt, J.-S.; Winkler, J.; Schoemaker, R. Population Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Fepixnebart (LY3016859) and Epiregulin in Patients with Chronic Pain. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2025, 64, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, L.; Vale, N. Toward Personalized Salbutamol Therapy: Validating Virtual Patient-Derived Population Pharmacokinetic Model with Real-World Data. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewski, J.; Brandhorst, J.; Green, K.; Eleftheriadou, D.; Duport, Y.; Barthorscht, F.; Köller, A.; Ke, D.Y.J.; De Angelis, S.; König, M. PK-DB: Pharmacokinetics Database for Individualized and Stratified Computational Modeling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1358–D1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köller, A.; Grzegorzewski, J.; Tautenhahn, H.-M.; König, M. Prediction of Survival After Partial Hepatectomy Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model of Indocyanine Green Liver Function Tests. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 730418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewski, J.; Brandhorst, J.; König, M. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling of the Role of CYP2D6 Polymorphism for Metabolic Phenotyping with Dextromethorphan. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1029073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.; Costa, B.; Vale, N. New Data for Nebivolol after In Silico PK Study: Focus on Young Patients and Dosage Regimen. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barré-Sinoussi, F.; Montagutelli, X. Animal Models Are Essential to Biological Research: Issues and Perspectives. Future Sci. OA 2015, 1, FSO63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.C.J.; Grieder, F.B. The Continued Importance of Animals in Biomedical Research. Lab Anim. 2024, 53, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, D.; Nandi, S.K. Role of Animal Models in Biomedical Research: A Review. Lab. Anim. Res. 2022, 38, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jota Baptista, C.V.; Faustino-Rocha, A.I.; Oliveira, P.A. Animal Models in Pharmacology: A Brief History Awarding the Nobel Prizes for Physiology or Medicine. Pharmacology 2021, 106, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, X.; Lu, C. PBPK Modeling and Simulation in Drug Research and Development. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2016, 6, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martignoni, M.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; de Kanter, R. Species Differences between Mouse, Rat, Dog, Monkey and Human CYP-Mediated Drug Metabolism, Inhibition and Induction. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2006, 2, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, I. Misconceptions and Issues Regarding Allometric Scaling during the Drug Development Process. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattani, A.; Khurade, K.; Tripathi, R.; Seetharaman, R.; Jalgaonkar, S. A Comprehensive Analysis of Use of Small Laboratory Animals in Preclinical Research: A Five-Year Quantitative Descriptive Analysis. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2025, 16, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, T. The (Misleading) Role of Animal Models in Drug Development. Front. Drug Discov. 2024, 4, 1355044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.T.; George, G.C.; Hess, K.; Marcelo-Lewis, K.L.; Yuan, Y.; Borthakur, G.; Khozin, S.; LoRusso, P.; Hong, D.S. Pre-Clinical Animal Models Are Poor Predictors of Human Toxicities in Phase 1 Oncology Clinical Trials. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.B.; Krieger, K.; Khan, F.M.; Huffman, W.; Chang, M.; Naik, A.; Yongle, R.; Hameed, I.; Krieger, K.; Girardi, L.N.; et al. The Current State of Animal Models in Research: A Review. Int. J. Surg. 2019, 72, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kararli, T.T. Comparison of the Gastrointestinal Anatomy, Physiology, and Biochemistry of Humans and Commonly Used Laboratory Animals. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 1995, 16, 351–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leenaars, C.H.C.; Kouwenaar, C.; Stafleu, F.R.; Bleich, A.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; De Vries, R.B.M.; Meijboom, F.L.B. Animal to Human Translation: A Systematic Scoping Review of Reported Concordance Rates. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perel, P.; Roberts, I.; Sena, E.; Wheble, P.; Briscoe, C.; Sandercock, P.; Macleod, M.; Mignini, L.E.; Jayaram, P.; Khan, K.S. Comparison of Treatment Effects between Animal Experiments and Clinical Trials: Systematic Review. BMJ 2007, 334, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.-Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, D.; Chu, C.; Hong, Y.; Tao, M.; Hu, H.; Xu, M.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y. Human Organoids in Basic Research and Clinical Applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brevini, T.; Tysoe, O.C.; Sampaziotis, F. Tissue Engineering of the Biliary Tract and Modelling of Cholestatic Disorders. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 918–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Organogenesis in a Dish: Modeling Development and Disease Using Organoid Technologies. Science 2014, 345, 1247125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzelmann, E.; Piraino, F.; Costa, M.; Roch, A.; Norkin, M.; Garnier, V.; Homicsko, K.; Brandenberg, N. IPSC-Derived and Patient-Derived Organoids: Applications and Challenges in Scalability and Reproducibility as Pre-Clinical Models. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 7, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrò, C.; Novellasdemunt, L.; Li, V.S.W. A Brief History of Organoids. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2020, 319, C151–C165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hu, H.; Kung, H.; Zou, R.; Dai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, T.; Lv, T.; Yu, J.; Li, F. Organoids: The Current Status and Biomedical Applications. MedComm 2023, 4, e274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.M.; Chen, C.S. Deconstructing the Third Dimension—How 3D Culture Microenvironments Alter Cellular Cues. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 3015–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraswathibhatla, A.; Indana, D.; Chaudhuri, O. Cell–Extracellular Matrix Mechanotransduction in 3D. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Vries, R.G.; Snippert, H.J.; van de Wetering, M.; Barker, N.; Stange, D.E.; van Es, J.H.; Abo, A.; Kujala, P.; Peters, P.J.; et al. Single Lgr5 Stem Cells Build Crypt-Villus Structures in Vitro without a Mesenchymal Niche. Nature 2009, 459, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, R.; Shimizu, H.; Suzuki, K.; Kawamoto, A.; Takahashi, J.; Kawai, M.; Nagata, S.; Hiraguri, Y.; Takeoka, S.; Sugihara, H.Y.; et al. Organoid-Based Regenerative Medicine for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Regen. Ther. 2020, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cong, L.; Cong, X. Patient-Derived Organoids in Precision Medicine: Drug Screening, Organoid-on-a-Chip and Living Organoid Biobank. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 762184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Nishikawa, M.; Kutsuzawa, N.; Tokito, F.; Kobayashi, T.; Kurniawan, D.A.; Shioda, H.; Cao, W.; Shinha, K.; Nakamura, H.; et al. Advancements in Microphysiological Systems: Exploring Organoids and Organ-on-a-Chip Technologies in Drug Development -Focus on Pharmacokinetics Related Organs. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2025, 60, 101046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Gu, Q.; Li, G.; Li, Z.A.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J.; Tuan, R.S. Organoids and Organs-on-Chips: Recent Advances, Applications in Drug Development, and Regulatory Challenges. Med 2025, 6, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ma, L.; Song, J.; Xue, L. Synergistic Innovation in Organ-on-a-Chip and Organoid Technologies: Reshaping the Future of Disease Modeling, Drug Development and Precision Medicine. Protein Cell 2025, pwaf058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA Pushes to Replace Animal Testing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 655. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chang, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Y.; Cai, Y.; Gu, Z.; Xie, Z. Organoids Pharmacology and Toxicology. EngMedicine 2025, 2, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.M.; Strong, J.M.; Zhang, L.; Reynolds, K.S.; Nallani, S.; Temple, R.; Abraham, S.; Habet, S.A.; Baweja, R.K.; Burckart, G.J.; et al. New Era in Drug Interaction Evaluation: US Food and Drug Administration Update on CYP Enzymes, Transporters, and the Guidance Process. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 48, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Brown, P.C.; Chow, E.C.Y.; Ewart, L.; Ferguson, S.S.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Freedman, B.S.; Guo, G.L.; Hedrich, W.; Heyward, S.; et al. 3D Cell Culture Models: Drug Pharmacokinetics, Safety Assessment, and Regulatory Consideration. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 1659–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.J.S.; Yang, X.; Patel, V.; Madabushi, R.; Strauss, D.G. Liver Microphysiological Systems for Predicting and Evaluating Drug Effects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 106, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudy, A.R.; Otieno, M.A.; Hewitt, P.; Gan, J.; Roth, A.; Keller, D.; Sura, R.; Van Vleet, T.R.; Proctor, W.R. Liver Microphysiological Systems Development Guidelines for Safety Risk Assessment in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S.; Chen, W.L.K.; Duignan, D.B.; Gupta, A.; Hariparsad, N.; Kenny, J.R.; Lai, W.G.; Liras, J.; Phillips, J.A.; Gan, J. Microphysiological Systems for ADME-Related Applications: Current Status and Recommendations for System Development and Characterization. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, M.; Lutolf, M.P. Engineering Organoids. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.G.; Daley, G.Q. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells in Disease Modelling and Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Charton, C.; Shim, J.H.; Lim, S.Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Ohn, J.H.; Kim, B.K.; Heo, C.Y. Patient-Derived Organoids Recapitulate Pathological Intrinsic and Phenotypic Features of Fibrous Dysplasia. Cells 2024, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Koo, B.-K.; Knoblich, J.A. Human Organoids: Model Systems for Human Biology and Medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, H.A.; Wells, J.M. Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Organoids: Using Principles of Developmental Biology to Grow Human Tissues in a Dish. Development 2017, 144, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narsinh, K.H.; Plews, J.; Wu, J.C. Comparison of Human Induced Pluripotent and Embryonic Stem Cells: Fraternal or Identical Twins? Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogberg, H.T.; Bressler, J.; Christian, K.M.; Harris, G.; Makri, G.; O’Driscoll, C.; Pamies, D.; Smirnova, L.; Wen, Z.; Hartung, T. Toward a 3D Model of Human Brain Development for Studying Gene/Environment Interactions. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 4, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Renner, M.; Martin, C.-A.; Wenzel, D.; Bicknell, L.S.; Hurles, M.E.; Homfray, T.; Penninger, J.M.; Jackson, A.P.; Knoblich, J.A. Cerebral Organoids Model Human Brain Development and Microcephaly. Nature 2013, 501, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimeault, M.; Hauke, R.; Mehta, P.P.; Batra, S.K. Recent Advances in Cancer Stem/Progenitor Cell Research: Therapeutic Implications for Overcoming Resistance to the Most Aggressive Cancers. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 981–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, J.; Xin, X.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Mei, X.; Li, M. Merits and Challenges of IPSC-Derived Organoids for Clinical Applications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1188905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yang, S.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, S.-N.; Jeong, J.-S.; Kim, K.Y.; Jung, C.-R.; Jeon, S.; Kwon, D.; Lee, S.; et al. Standardization and Quality Assessment for Human Intestinal Organoids. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1383893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, S.; Wu, W.; Wang, J.; Qian, G.; et al. Standardization of Organoid Culture in Cancer Research. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 14375–14386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Khutsishvili, D.; Tang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Dai, X.; Ma, S. Bridging the Organoid Translational Gap: Integrating Standardization and Micropatterning for Drug Screening in Clinical and Pharmaceutical Medicine. Life Med. 2024, 3, lnae016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, H.; Yu, Y. Living Biobank: Standardization of Organoid Construction and Challenges. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 3050–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.; Wang, Z.; Bai, J.; Sun, W.; Peng, W.K.; Huang, R.Y.; Thiery, J.; Kamm, R.D. Rapid Prototyping of Concave Microwells for the Formation of 3D Multicellular Cancer Aggregates for Drug Screening. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraino, F.; Selimović, Š.; Adamo, M.; Pero, A.; Manoucheri, S.; Bok Kim, S.; Demarchi, D.; Khademhosseini, A. Polyester μ-Assay Chip for Stem Cell Studies. Biomicrofluidics 2012, 6, 044109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selimović, Š.; Piraino, F.; Bae, H.; Rasponi, M.; Redaelli, A.; Khademhosseini, A. Microfabricated Polyester Conical Microwells for Cell Culture Applications. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenberg, N.; Hoehnel, S.; Kuttler, F.; Homicsko, K.; Ceroni, C.; Ringel, T.; Gjorevski, N.; Schwank, G.; Coukos, G.; Turcatti, G.; et al. High-Throughput Automated Organoid Culture via Stem-Cell Aggregation in Microcavity Arrays. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.; Mouradov, D.; Lee, M.; Gard, G.; Hirokawa, Y.; Li, S.; Lin, C.; Li, F.; Luo, H.; Wu, K.; et al. Unified Framework for Patient-Derived, Tumor-Organoid-Based Predictive Testing of Standard-of-Care Therapies in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjorevski, N.; Sachs, N.; Manfrin, A.; Giger, S.; Bragina, M.E.; Ordóñez-Morán, P.; Clevers, H.; Lutolf, M.P. Designer Matrices for Intestinal Stem Cell and Organoid Culture. Nature 2016, 539, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Cui, K.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, J. Advances in Hydrogels in Organoids and Organs-on-a-Chip. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1902042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, H.; Sanford, K.; Szwedo, P.K.; Pathak, R.; Ghosh, A. Synthetic Matrices for Intestinal Organoid Culture: Implications for Better Performance. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Maibam, M.; Jain, R.; Aggarwal, K.; Sahu, A.K.; Gupta, P.; Paul, S.; Bisht, B.; Paul, M.K. Organoid: Biomedical Application, Biobanking, and Pathways to Translation. Heliyon 2025, 11, e43028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, G.; Di Bonito, M.; Cantile, M. Organoid Biobanks as a New Tool for Pre-Clinical Validation of Candidate Drug Efficacy and Safety. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 13, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation Hubrecht Organoid Biobank. Available online: https://www.hubrechtorganoidbiobank.org (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Xie, X.; Li, X.; Song, W. Tumor Organoid Biobank-New Platform for Medical Research. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, J.P.; Schwab, K.H.; Har-el, Y.; Gerstenhaber, J.A.; Lelkes, P.I. Bioreactor Technologies for Enhanced Organoid Culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Marsee, A.; van Tienderen, G.S.; Rezaeimoghaddam, M.; Sheikh, H.; Samsom, R.-A.; de Koning, E.J.P.; Fuchs, S.; Verstegen, M.M.A.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; et al. Accelerated Production of Human Epithelial Organoids in a Miniaturized Spinning Bioreactor. Cell Rep. Methods 2024, 4, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Jacob, F.; Song, M.M.; Nguyen, H.N.; Song, H.; Ming, G. Generation of Human Brain Region–Specific Organoids Using a Miniaturized Spinning Bioreactor. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashimoto, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Kunita, I.; Nakamasu, A.; Torisawa, Y.; Nakayama, M.; Takigawa-Imamura, H.; Kotera, H.; Nishiyama, K.; Miura, T.; et al. Integrating Perfusable Vascular Networks with a Three-Dimensional Tissue in a Microfluidic Device. Integr. Biol. 2017, 9, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, C.W.; Ritsma, L.; Avramut, M.C.; Wiersma, L.E.; van den Berg, B.M.; Leuning, D.G.; Lievers, E.; Koning, M.; Vanslambrouck, J.M.; Koster, A.J.; et al. Renal Subcapsular Transplantation of PSC-Derived Kidney Organoids Induces Neo-Vasculogenesis and Significant Glomerular and Tubular Maturation In Vivo. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 10, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, L.; Shi, T.; Xiao, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xue, F.; Zeng, W. Review on the Vascularization of Organoids and Organoids-on-a-Chip. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 637048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-Y.; Ju, X.-C.; Li, Y.; Zeng, P.-M.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.-Y.; Shen, L.-B.; Dong, J.; Chen, Y.-J.; Luo, Z.-G. Generation of Vascularized Brain Organoids to Study Neurovascular Interactions. eLife 2022, 11, e76707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.M.; de Haan, P.; Ronaldson-Bouchard, K.; Kim, G.-A.; Ko, J.; Rho, H.S.; Chen, Z.; Habibovic, P.; Jeon, N.L.; Takayama, S.; et al. A Guide to the Organ-on-a-Chip. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Mathur, A.; Arora, S.; Roy, S.; Mahindroo, N. Journey of Organ on a Chip Technology and Its Role in Future Healthcare Scenario. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 9, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, W.J.; Vatti, S.; Sakamoto, T.; Li, W.; Odutola, S.R.; Liu, C.; Chen, G.; Boehm, M.; Mukouyama, Y. In Vivo Transplantation of Mammalian Vascular Organoids onto the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane Reveals the Formation of a Hierarchical Vascular Network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werschler, N.; Quintard, C.; Nguyen, S.; Penninger, J. Engineering next Generation Vascularized Organoids. Atherosclerosis 2024, 398, 118529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konoe, R.; Morizane, R. Strategies for Improving Vascularization in Kidney Organoids: A Review of Current Trends. Biology 2023, 12, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaduri, A.; Andrews, M.G.; Mancia Leon, W.; Jung, D.; Shin, D.; Allen, D.; Jung, D.; Schmunk, G.; Haeussler, M.; Salma, J.; et al. Cell Stress in Cortical Organoids Impairs Molecular Subtype Specification. Nature 2020, 578, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Song, H.; Ming, G. Brain Organoids: Advances, Applications and Challenges. Development 2019, 146, dev166074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, E.; Muotri, A.R.; Engler, A.J. Recent Advancements and Future Requirements in Vascularization of Cortical Organoids. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1048731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, T.; Huang, Q.; Wang, Y. From Organ-on-a-Chip to Human-on-a-Chip: A Review of Research Progress and Latest Applications. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 3466–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saorin, G.; Caligiuri, I.; Rizzolio, F. Microfluidic Organoids-on-a-Chip: The Future of Human Models. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 144, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.R.; Mayhew, C.N.; Rankin, S.A.; Kuhar, M.F.; Vallance, J.E.; Tolle, K.; Hoskins, E.E.; Kalinichenko, V.V.; Wells, S.I.; Zorn, A.M.; et al. Directed Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells into Intestinal Tissue in Vitro. Nature 2011, 470, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Z.; Cai, B.; Cheng, Y.; Du, Y.; Ou, S.; Chen, H.; Pan, M.; Liu, H.; et al. Reprogramming Human Urine Cells into Intestinal Organoids with Long-Term Expansion Ability and Barrier Function. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Qi, Y.; Rollins, D.; Bussiere, L.D.; Dhar, D.; Miller, C.L.; Yu, C.; Wang, Q. Rational Design of Oral Drugs Targeting Mucosa Delivery with Gut Organoid Platforms. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 30, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Sato, S.; Kurashima, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Kurokawa, S.; Yuki, Y.; Takemura, N.; Uematsu, S.; Lai, C.-Y.; Otsu, M.; et al. A Refined Culture System for Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Intestinal Epithelial Organoids. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 10, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belair, D.G.; Visconti, R.J.; Hong, M.; Marella, M.; Peters, M.F.; Scott, C.W.; Kolaja, K.L. Human Ileal Organoid Model Recapitulates Clinical Incidence of Diarrhea Associated with Small Molecule Drugs. Toxicol. Vitr. 2020, 68, 104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.F.; Landry, T.; Pin, C.; Maratea, K.; Dick, C.; Wagoner, M.P.; Choy, A.L.; Barthlow, H.; Snow, D.; Stevens, Z.; et al. Human 3D Gastrointestinal Microtissue Barrier Function As a Predictor of Drug-Induced Diarrhea. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 168, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, J.; Sugihara, H.Y.; Kato, S.; Nagata, S.; Okamoto, R.; Mizutani, T. Protocol to Generate Large Human Intestinal Organoids Using a Rotating Bioreactor. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Puschhof, J.; van den Brink, S.; Geurts, V.; Beumer, J.; Clevers, H. Establishment and Culture of Human Intestinal Organoids Derived from Adult Stem Cells. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2020, 130, e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onozato, D.; Yamashita, M.; Nakanishi, A.; Akagawa, T.; Kida, Y.; Ogawa, I.; Hashita, T.; Iwao, T.; Matsunaga, T. Generation of Intestinal Organoids Suitable for Pharmacokinetic Studies from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1572–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, T.; Nakamura, T.; Morikawa, R.; Fukuda, M.; Mochizuki, W.; Yamauchi, Y.; Nozaki, K.; Yui, S.; Nemoto, Y.; Nagaishi, T.; et al. Real-Time Analysis of P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Drug Transport across Primary Intestinal Epithelium Three-Dimensionally Cultured in Vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 419, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Liu, M.; Wang, X. Measurement of Rhodamine 123 in Three-Dimensional Organoids: A Novel Model for P-Glycoprotein Inhibitor Screening. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 119, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Mochizuki, T.; Baba, S.; Kawai, S.; Nakano, K.; Tachibana, T.; Uchimura, K.; Kato, A.; Miyayama, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; et al. Robust and Reproducible Human Intestinal Organoid-Derived Monolayer Model for Analyzing Drug Absorption. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Amako, J.; Watanabe, T.; Shiraki, N.; Kume, S. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Intestinal Organoids for Pharmacokinetic Studies. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2025, 104, 151489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M.; Matano, M.; Toshimitsu, K.; Takano, A.; Mikami, Y.; Nishikori, S.; Sugimoto, S.; Sato, T. Human Intestinal Organoids Maintain Self-Renewal Capacity and Cellular Diversity in Niche-Inspired Culture Condition. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 787–793.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Stange, D.E.; Ferrante, M.; Vries, R.G.J.; van Es, J.H.; van den Brink, S.; van Houdt, W.J.; Pronk, A.; van Gorp, J.; Siersema, P.D.; et al. Long-Term Expansion of Epithelial Organoids from Human Colon, Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s Epithelium. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1762–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, T.; Shinozawa, T. Human Organoids for Predictive Toxicology Research and Drug Development. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 767621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bein, A.; Shin, W.; Jalili-Firoozinezhad, S.; Park, M.H.; Sontheimer-Phelps, A.; Tovaglieri, A.; Chalkiadaki, A.; Kim, H.J.; Ingber, D.E. Microfluidic Organ-on-a-Chip Models of Human Intestine. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 5, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasendra, M.; Tovaglieri, A.; Sontheimer-Phelps, A.; Jalili-Firoozinezhad, S.; Bein, A.; Chalkiadaki, A.; Scholl, W.; Zhang, C.; Rickner, H.; Richmond, C.A.; et al. Development of a Primary Human Small Intestine-on-a-Chip Using Biopsy-Derived Organoids. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, H.; Betton, G.; Robinson, D.; Thomas, K.; Monro, A.; Kolaja, G.; Lilly, P.; Sanders, J.; Sipes, G.; Bracken, W.; et al. Concordance of the Toxicity of Pharmaceuticals in Humans and in Animals. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2000, 32, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.-K.; Huch, M. Organoids: A New in Vitro Model System for Biomedical Science and Disease Modelling and Promising Source for Cell-Based Transplantation. Dev. Biol. 2016, 420, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Manfrin, A.; Lutolf, M.P. Progress and Potential in Organoid Research. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y. Advancing Hepatotoxicity Assessment: Current Advances and Future Directions. Toxicol. Res. 2025, 41, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C. Proceedings of a Workshop to Address Animal Methods Bias in Scientific Publishing. ALTEX 2022, 40, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, X.; Luo, J.; Huang, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y.; Wu, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, L.; et al. Liver Organoid Culture Methods. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cheng, C.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, T.; Wang, Z.; Yi, X.; Yan, F.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Cui, T.; et al. Liver Organoids: Updates on Generation Strategies and Biomedical Applications. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mun, S.J.; Ryu, J.-S.; Lee, M.-O.; Son, Y.S.; Oh, S.J.; Cho, H.-S.; Son, M.-Y.; Kim, D.-S.; Kim, S.J.; Yoo, H.J.; et al. Generation of Expandable Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Hepatocyte-Like Liver Organoids. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 970–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Im, I.; Jeon, J.S.; Kang, E.-H.; Lee, H.-A.; Jo, S.; Kim, J.-W.; Woo, D.-H.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Development of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Hepatic Organoids as an Alternative Model for Drug Safety Assessment. Biomaterials 2022, 286, 121575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgodda, M.; Dai, Z.; Zweigerdt, R.; Sharma, A.D.; Ott, M.; Cantz, T. A Scalable Approach for the Generation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Hepatic Organoids with Sensitive Hepatotoxicity Features. Stem Cells Dev. 2017, 26, 1490–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, S.D.; Devarasetty, M.; Shupe, T.; Bishop, C.; Atala, A.; Soker, S.; Skardal, A. Environmental Toxin Screening Using Human-Derived 3D Bioengineered Liver and Cardiac Organoids. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozawa, T.; Kimura, M.; Cai, Y.; Saiki, N.; Yoneyama, Y.; Ouchi, R.; Koike, H.; Maezawa, M.; Zhang, R.-R.; Dunn, A.; et al. High-Fidelity Drug-Induced Liver Injury Screen Using Human Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Organoids. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 831–846.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Soto-Gutierrez, A.; Baptista, P.M.; Spee, B. Biotechnology Challenges to In Vitro Maturation of Hepatic Stem Cells. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1258–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidecker, B.; Shinohara, M.; Sugimoto, M.; Danoy, M.; Nishikawa, M.; Sakai, Y. Induction of in Vitro Metabolic Zonation in Primary Hepatocytes Requires Both Near-Physiological Oxygen Concentration and Flux. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, T.; Danoy, M.; Khadim, R.R.; Tokito, F.; Arakawa, H.; Kato, Y.; Kido, T.; Miyajima, A.; Nishikawa, M.; Sakai, Y. A Highly Efficient Cell Culture Method Using Oxygen-permeable PDMS-based Honeycomb Microwells Produces Functional Liver Organoids from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived Carboxypeptidase M Liver Progenitor Cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 1177–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshdel-Rad, N.; Ahmadi, A.; Moghadasali, R. Kidney Organoids: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 387, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, M.H.; Combes, A.N. Kidney Organoids: Accurate Models or Fortunate Accidents. Genes. Dev. 2019, 33, 1319–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-Y.; Evangelista, E.A.; Yang, J.; Kelly, E.J.; Yeung, C.K. Kidney Organoid and Microphysiological Kidney Chip Models to Accelerate Drug Development and Reduce Animal Testing. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 695920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

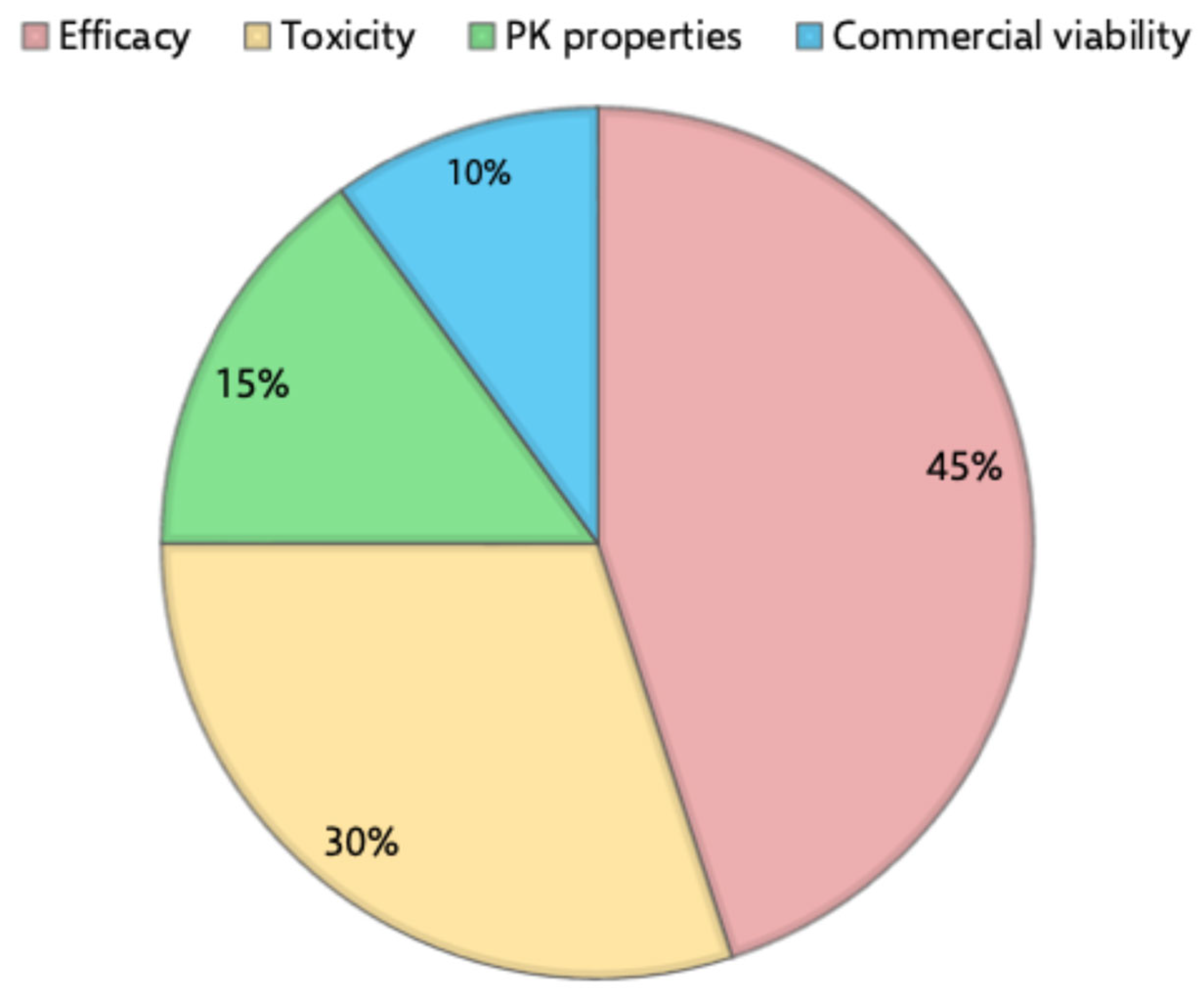

- Dowden, H.; Munro, J. Trends in Clinical Success Rates and Therapeutic Focus. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 495–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.K. Phase II and Phase III Failures: 2013–2015. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; Zhou, S. Why 90% of Clinical Drug Development Fails and How to Improve It? Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, J.Y.-C.; Jansen, J.; Masereeuw, R.; Little, M.H. Advances in Predictive in Vitro Models of Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, G.S.; Bomback, A.S.; Perazella, M.A. Drug-Induced Glomerular Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerniecki, S.M.; Cruz, N.M.; Harder, J.L.; Menon, R.; Annis, J.; Otto, E.A.; Gulieva, R.E.; Islas, L.V.; Kim, Y.K.; Tran, L.M.; et al. High-Throughput Screening Enhances Kidney Organoid Differentiation from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells and Enables Automated Multidimensional Phenotyping. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 929–940.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesRochers, T.M.; Suter, L.; Roth, A.; Kaplan, D.L. Bioengineered 3D Human Kidney Tissue, a Platform for the Determination of Nephrotoxicity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasato, M.; Er, P.X.; Chiu, H.S.; Maier, B.; Baillie, G.J.; Ferguson, C.; Parton, R.G.; Wolvetang, E.J.; Roost, M.S.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; et al. Kidney Organoids from Human IPS Cells Contain Multiple Lineages and Model Human Nephrogenesis. Nature 2015, 526, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.A.; Holland, I.; Gül, H. Kidney Organoids: Steps towards Better Organization and Function. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2024, 52, 1861–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, B.; Achour, B.; Artursson, P.; Hop, C.E.C.A.; Lai, Y.; Smith, P.C.; Barber, J.; Wisniewski, J.R.; Spellman, D.; Uchida, Y.; et al. Toward a Consensus on Applying Quantitative Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Proteomics in Translational Pharmacology Research: A White Paper. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 106, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, B.; Johnson, K.; Billington, S.; Lee, C.; Chung, G.W.; Brown, C.D.A.; Kelly, E.J.; Himmelfarb, J.; Unadkat, J.D. Abundance of Drug Transporters in the Human Kidney Cortex as Quantified by Quantitative Targeted Proteomics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 1920–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweet, D.H.; Eraly, S.A.; Vaughn, D.A.; Bush, K.T.; Nigam, S.K. Organic Anion and Cation Transporter Expression and Function during Embryonic Kidney Development and in Organ Culture Models. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, H.; Sakurai, Y.; Saito, H.; Masuda, S.; Urakami, Y.; Goto, M.; Fukatsu, A.; Ogawa, O.; Inui, K. Gene Expression Levels and Immunolocalization of Organic Ion Transporters in the Human Kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Isoherranen, N. Novel Mechanistic PBPK Model to Predict Renal Clearance in Varying Stages of CKD by Incorporating Tubular Adaptation and Dynamic Passive Reabsorption. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2020, 9, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büning, A.; Reckzeh, E. Opportunities of Patient-derived Organoids in Drug Development. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yu, Y. Patient-Derived Organoids in Translational Oncology and Drug Screening. Cancer Lett. 2023, 562, 216180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Representativeness in Preclinical Studies (n, %) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | 639 (75.98%) | Widely used due to low cost, ease of handling, rapid breeding, and availability of genetically modified strains. | Smal body size may limit the volume of blood/tissue sampling; some physiological processes may differ from humans, requiring careful translation. |

| Rat | 186 (22.12%) | Larger sizes enable easier surgical manipulation and sampling; physiologically closer to humans in cardiovascular and metabolic functions. | Genetic manipulation is less advanced. |

| Dog | ND | Physiology and size make them useful translational models for PK. | High cost, ethical concerns, and lower genetic tractability compared to rodent models. |

| Non-human primates | ND | High protein sequence and physiological similarity to humans; often best predictor of drug clearance. | Expensive, ethical and logistical challenges; limited access. |

| Pig | ND | Useful for skin, cardiovascular, and GI studies. Anatomic and physiological similarities make them valuable for translational research. | Lower availability in PK-specific applications and limited genetic tools. |

| Guinea pig | 1 (0.12%) | Useful for specific toxicology or immunological studies. | Limited utility in PK studies due to varying metabolism pathways and less detailed physiological characterization. |

| Rabbit | 15 (1.78%) |

| Limitation | Description |

|---|---|

| Regulatory compliance and ethical considerations | Development and establishment of clinical-grade iPSCs must comply with strict ethical and legal guidelines, limiting access and scalability. |

| Lack of standardized protocols | Variability in iPSC generation and differentiation methods leads to inconsistent cell quality, affecting reproducibility and cross-study reliability. |

| Limited biobank diversity | iPSC biobanks often lack sufficient representation of diverse ethnic, genetic, and gender backgrounds, restricting generalizability. |

| Resource-intensive processes | iPSC-based organoid development is labor-intensive and costly, requiring specialized infrastructure, equipment, and technical expertise. |

| Cellular immaturity | Many iPSC-derived cells display immature phenotypes, resembling embryonic or fetal stages, which may limit their relevance for adult disease modeling or PK studies. |

| Incomplete regional identity | Organoids may not fully represent the specific anatomical or functional region of the organ being modeled, limiting precision in data generation. |

| Limitation | Strategies to Overcome | References |

|---|---|---|

| Low efficiency and reproducibility of protocols |

| [131,132,133,134] |

| [135,136,137,138,139] | |

| [140,141,142] | |

| [134,143,144,145,146] | |

| High costs associated with organoid generation |

| [147,148,149] |

| [140,141,142] | |

| Micron scale and lack of vascularization |

| [150,151,152,153] |

| [154,155] | |

| [156,157,158] | |

| Ethical concerns |

| - |

| - | |

| - |

| Study | Cell Source | Key Factors | Main Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spence et al., 2011 [164] | Human PSCs | Activin A, FGF4, Wnt3a | Cell differentiation, epithelial morphogenesis, stem cell dynamics, and enteric formation |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [165] | Somatic cells from urine samples | Noggin, FGF4, CHIR99021, Sag, BMP4, FGF7, FGF10 | Precision medicine, drug metabolism studies, and barrier function assays |

| Tong et al., 2023 [166] | Mouse small intestine stem cells | R-spondin 1, Noggin, EGF | Evaluation of the transport efficiency of oral drug delivery vehicles |

| Takahashi et al., 2018 [167] | hiPSCs | Activin A, hWnt3a, hFGF2, hFGF4, EGF | HTS of pathogenic factors and candidate treatments for GI diseases |

| Belair et al., 2020 [168] | Adult human ileal small intestinal tissue | NA | Evaluation of GI toxicity associated with small molecule drugs |

| Peters et al., 2019 [169] | Primary human small intestine cells | NA | Evaluation of barrier function and prediction of drug-induced toxicity |

| Takahashi et al., 2023 [170] | hiPSCs | Activin A, CHIR99021, FGF4, Y-27632, EGF, Noggin, R-spondin 1, A83-01 | Disease modeling, drug screening, personalized medicine |

| Pleguezuelos-Manzano et al., 2020 [171] | ASCs | ENR, Notchi, MEKi, BMP4, BMP2 | Disease modeling, drug screening, personalized medicine |

| Limitation | Strategy to Overcome |

|---|---|

| Overexpression of transcription factors or miRNAs, as well as supplementation with growth factors or small molecules, to promote hepatocyte differentiation and maturation [194]. |

| Culturing liver organoids on oxygen-permeable plates or microwells has been shown to improve oxygen delivery, increasing albumin secretion and CYP-mediated metabolism [195,196]. |

| Primary tissue-derived organoids are more mature and exhibit greater genomic stability [187]. |

| Primary tissue-derived organoids are most cost-effective [187] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, L.; Vale, N. Organoids as a Revolutionary Data Source for Pharmacokinetic Modeling: A Comprehensive Review. Future Pharmacol. 2025, 5, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/futurepharmacol5040074

Marques L, Vale N. Organoids as a Revolutionary Data Source for Pharmacokinetic Modeling: A Comprehensive Review. Future Pharmacology. 2025; 5(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/futurepharmacol5040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Lara, and Nuno Vale. 2025. "Organoids as a Revolutionary Data Source for Pharmacokinetic Modeling: A Comprehensive Review" Future Pharmacology 5, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/futurepharmacol5040074

APA StyleMarques, L., & Vale, N. (2025). Organoids as a Revolutionary Data Source for Pharmacokinetic Modeling: A Comprehensive Review. Future Pharmacology, 5(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/futurepharmacol5040074