Revising the Compatibility of Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning Processes in the Coastal Zone of the Sonora State, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

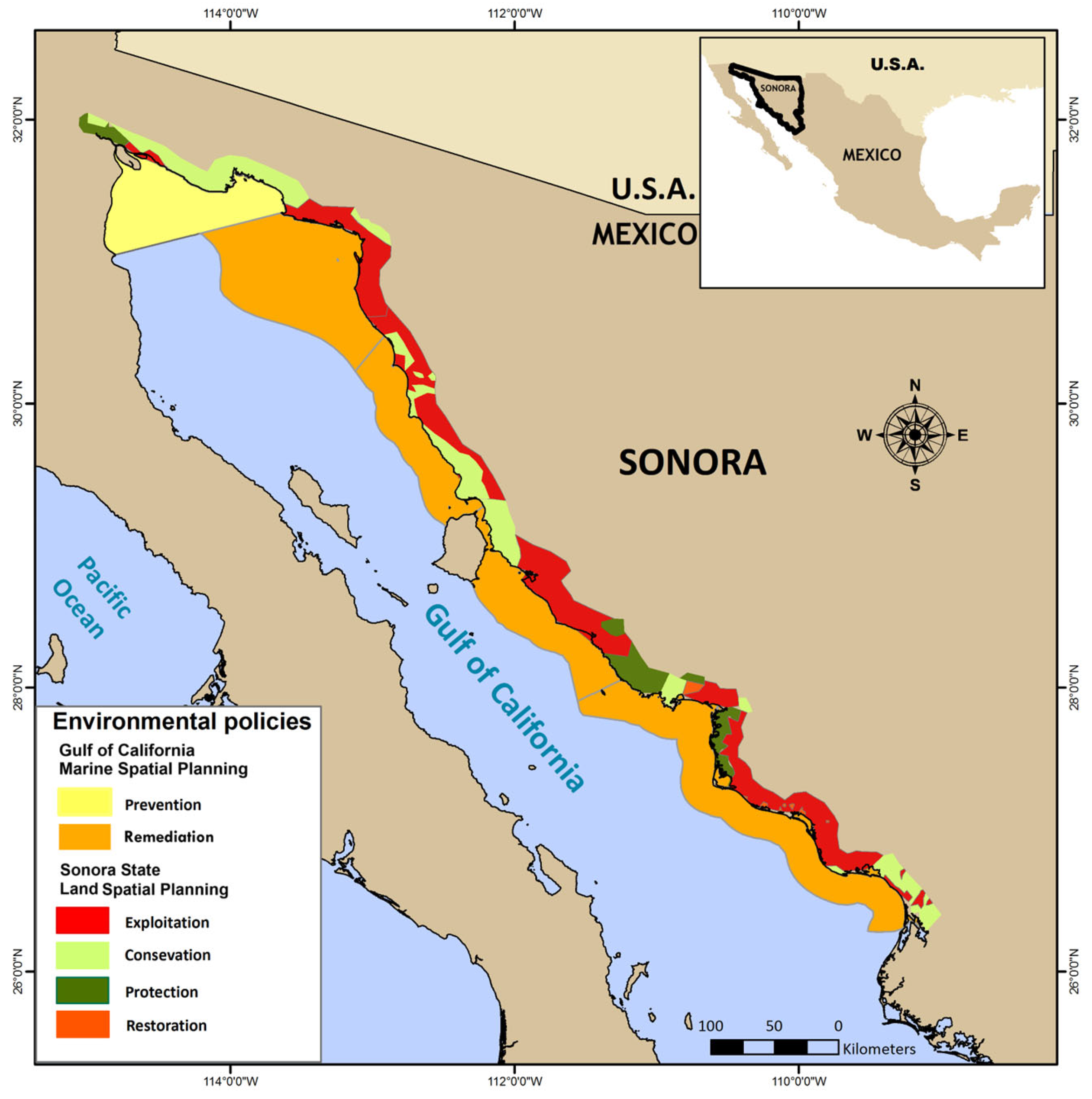

3.1. Environmental Policies in the Coastal Zone of Sonora

3.2. Spatial Integration of Environmental Policies in the Coastal Zone of Sonora

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSP-GC | Marine Spatial Planning of the Gulf of California |

| LSP-CS | Land Spatial Planning of the Coast Sonora |

References

- Newton, A.; Carruthers, T.J.B.; Icely, J. The coastal syndromes and hotspots on the coast. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2012, 96, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosby, A.G.; Lebakula, V.; Smith, C.N.; Wanik, D.W.; Bergene, K.; Rose, A.N.; Swanson, D.; Bloom, D.E. Accelerating growth of human coastal populations at the global and continent levels: 2000–2018. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.M.; Halpern, B.S.; Micheli, F.; Armsby, M.H.; Caldwell, M.R.; Crain, C.M.; Prahler, E.; Rohr, N.; Sivas, D.; Beck, M.W.; et al. Guiding ecological principles for marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, F. The international legal framework for marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehler, C.N. Perspective: The Present and Future of Marine Spatial Planning around the World. Mar. Ecosyst. Manag. 2013, 6, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO-IOC/European Commission. MSPglobal International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning. Paris, UNESCO. (IOC Manuals and Guides no 89). 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379196 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Frazão Santos, C.; Wedding, L.M.; Agardy, T.; Reimer, J.M.; Gissi, L.; Calado, H. Marine spatial planning and marine protected area planning are not the same and both are key for sustainability in a changing ocean. Npj Ocean. Sustain. 2025, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E.; Costa, E.M.; Abrantes, P. Spatial Planning and Land-Use Management. Land 2024, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LGEEPA. Ley General del Equilibrio Ecológico y la Protección al Ambiente: Última Reforma (General Law on Ecological Equilibrium and Environmental Protection: Last Reform). Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2015. Available online: http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- CIMARES. Política Nacional de Mares y Costas de México: Gestión Integral de las Regiones más Dinámicas del Territorio Nacional (National Policy of Seas and Coasts of Mexico: Integral Management of the Most Dynamic Regions of the National Territory); Comisión Intersecretarial para el Manejo Sustentable de Mares y Costas; Semarnat: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012; 97p. [Google Scholar]

- Rosete-Vergés, F.A.; Enríquez-Hernández, G.; Córdova-Vázquez, A. El ordenamiento ecológico marino y costero: Tendencias y perspectivas (Marine and coastal spatial planning: Trends and perspectives). Gac. Ecológica 2006, 78, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Von Storch, H.; Emeis, K.; Meinke, I.; Kannen, A.; Matthias, V. Making coastal research useful—Cases from practice. Oceanologia 2015, 57, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, E. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Köppen (Modifications to Köppen’s Climate Classification System), 5th ed.; Instituto de Geografía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Cd.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Filloux, J.H. Tidal Patterns and Energy Balance in the Gulf of California. Nature 1973, 243, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020 (Population and Housing Census 2010). Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- DOF. Acuerdo por el que se expide el Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Marino del Golfo de California (Agreement Establishing the Marine Spatial Planning Progam of the Gulf of California). Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2006. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4940652&fecha=15/12/2006#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- BOGES. Boletín Oficial del Gobierno del Estado de Sonora. Aprobación del Programa de Ordenamiento Territorial de la Costa de Sonora (Approve of the Program Land Spatial Planning of the Coastal Sonora). 2008. Available online: https://boletinoficial.sonora.gob.mx/images/boletines/2008/09/2008CLXXXII25V.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- DOF. Decreto por el cual se aprueba el Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Marino del Golfo de California (Decree approving the Marine Spatial Planning Program of the Gulf of California). Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2006. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4938943&fecha=29/11/2006#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- SEMARNAT-CEDES. Formulación del Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Territorial de Sonora. Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Comisión de Ecología y Desarrollo Sustentable del Estado de Sonora. 2011. Available online: https://archivos.cedes.gob.mx/resources/CVRJAUU9YWCVDCG3MUST.76a26a593366dda353052f07e6323a8d.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- BOGES. Boletín Oficial del Gobierno del Estado de Sonora. Decreto del Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Territorial del Estado de Sonora (Decree of the Program Land Spatial Planning of the Coastal Sonora). 2015. Available online: https://boletinoficial.sonora.gob.mx/boletin/images/boletinesPdf/2015/mayo/2015CXCV41III.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Ruttenberg, B.I.; Granek, E.F. Bridging the marine–terrestrial disconnect to improve marine coastal zone science and management. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 434, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Romero, J.A.; Pressey, R.L.; Ban, N.C.; Vance-Borland, K.; Willer, C.; Klein, C.J.; Gaines, S.D. Integrated Land-Sea Conservation Planning: The Missing Links. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015, 42, 381–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallis, H.; Ferdana, Z.; Gray, E. Linking terrestrial and marine conservation planning and threats analysis. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, A.; Musco, F. Land–Sea Interactions: A Spatial Planning Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasman, C. Implementing marine spatial planning: A policy perspective. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicin-Sain, B.; Belfiore, S. Linking marine protected areas to integrated coastal and ocean management: A review of theory and practice. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2005, 48, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.K.; Ruhl, J.B. Governing for Sustainable Coasts: Complexity, Climate Change, and Coastal Ecosystem Protection. Sustentability 2010, 2, 1361–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, T.A.; Farmer, C.J.Q. The development of world oceans & coasts and concepts of sustainability. Mar. Policy 2013, 42, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Mondragón, S.; Pedroza-Páez, D.; Bojórquez-Tapia, L.A.; Diíaz de-León, A.J. Contribución de la Planeación Espacial Marina en México a la Gestión Marino Costera (Contribution of Marine Spatial Planning in Mexico to Marine and Coastal Management). Costas 2021, 2, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Arreola-Lizárraga, J.A.; Juárez-Chávez, F.I.; Polanco-Mizquez, E.I.; Padilla-Arredondo, G. Análisis de la confluencia de tres ordenamientos en la zona costera de Guaymas, Sonora, México (Analysis of the confluence of three systems in the coastal zone of Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico). In Perspectivas del Ordenamiento Territorial y Ecológico en América y Europa (Perspectives of Territorial and Ecological Planning in America and Europe); Sorani, V., Alquicira-Arteaga, M.L., Eds.; Arlequin: Guadalajara, Jalisco, México, 2015; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, J.; Armitage, D. Governance across the land-sea interface: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 64, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.B.; Page, G.G.; Ochoa, E. The Analysis of Governance Responses to Ecosystem Change: A Handbook for Assembling a Baseline. In LOICZ Reports & Studies No. 34; GKSS Research Center: Geesthacht, Germany, 2009; 87p. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, K.E.; Juhn, D.; Grantham, H.S. Integrated land-sea management: Recommendations for planning, implementation and management. Environ. Conserv. 2016, 43, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.B.; McCann, J.H.; Fugate, G. The State of Rhode Island’s pioneering marine spatial plan. Mar. Policy 2014, 45, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Roe, M.H.; Cowie, P.J. Marine spatial planning and terrestrial spatial planning: Reflecting on new agendas. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 33, 1156–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, M.; Markovic, M.; Mlakar, A.; Stancheva, M.; Borg, M.; Carella, F.; Barbanti, A.; Ramieri, E. Land-Sea-Interactions in MSP and ICZM: A regional perspective from the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Mar. Policy 2023, 159, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOC-UNESCO/European Commission. Updated Joint Roadmap to accelerate Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning processes worldwide—MSProadmap (2022–2027). In IOC Technical Series, 182; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Environmental Policies of the Gulf of California Marine Spatial Planning (Source: DOF 2006) [16] | |

|---|---|

| Environmental Policy | Policy Description |

| Prevention | The approach is to maintain current levels of anthropogenic pressure, characterized by low levels of terrestrial pressure and medium levels of marine pressure. |

| Remediation | The approach is to reverse the trend of high anthropogenic pressure, defined as medium levels of terrestrial pressure combined with high levels of marine pressure. |

| Environmental Policies of the Sonora State Ecological Land Use Planning Program (Source: BOGES 2015) [20]. | |

| Environmental Policy | Policy Description |

| Exploitation | Irrigation agriculture is feasible with freshwater availability and is compatible with aquaculture, hunting activities, adventure tourism, and traditional sun-and-beach tourism. It is restricted by freshwater availability. |

| Conservation | Predominates in the buffer zone of two Protected Natural Areas and coastal-dune conservation areas; it is compatible with oyster farming, hunting, real-estate tourism, and adventure tourism. It is restricted by freshwater availability. |

| Protection | Wetlands, mountain ranges, dune ecosystems, and areas with columnar cacti and Boojum trees, already included in Protected Natural Areas. |

| Restoration | Wetlands of the Upper Gulf of California and Colorado River Delta (AGCDRC, in Spanish) Biosphere Reserve and approximately 36,200 ha of mangrove wetlands characterized by adverse anthropogenic impacts derived from pollutant inputs from industrial wastewater or urban sewage. |

| Sonora Coast Zone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | Legal Instrument | No. of EMUs | Environmental Policy | % Spatial Coverage |

| Marine | Gulf of California Marine Spatial Planning | 5 | Prevention | 10 |

| Remediation | ~90 | |||

| 100 | ||||

| Terrestrial | Sonora State Ecological Spatial Planning Program | 27 | Exploitation | 54 |

| Conservation | 32 | |||

| Protection | 12 | |||

| Restoration | 2 | |||

| 100 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juárez-Chávez, F.I.; Ruiz-Ruiz, T.M.; Polanco-Mizquez, E.I.; Salas-Mejía, N.; Arreola-Lizárraga, J.A. Revising the Compatibility of Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning Processes in the Coastal Zone of the Sonora State, Mexico. Coasts 2025, 5, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5040044

Juárez-Chávez FI, Ruiz-Ruiz TM, Polanco-Mizquez EI, Salas-Mejía N, Arreola-Lizárraga JA. Revising the Compatibility of Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning Processes in the Coastal Zone of the Sonora State, Mexico. Coasts. 2025; 5(4):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5040044

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuárez-Chávez, Fabiola Ivette, Thelma Michelle Ruiz-Ruiz, Elia Inés Polanco-Mizquez, Nathaly Salas-Mejía, and José Alfredo Arreola-Lizárraga. 2025. "Revising the Compatibility of Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning Processes in the Coastal Zone of the Sonora State, Mexico" Coasts 5, no. 4: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5040044

APA StyleJuárez-Chávez, F. I., Ruiz-Ruiz, T. M., Polanco-Mizquez, E. I., Salas-Mejía, N., & Arreola-Lizárraga, J. A. (2025). Revising the Compatibility of Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning Processes in the Coastal Zone of the Sonora State, Mexico. Coasts, 5(4), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5040044