Impact of Environmental Weathering on the Chemical Composition of Spilled Oils in a Real Case in Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

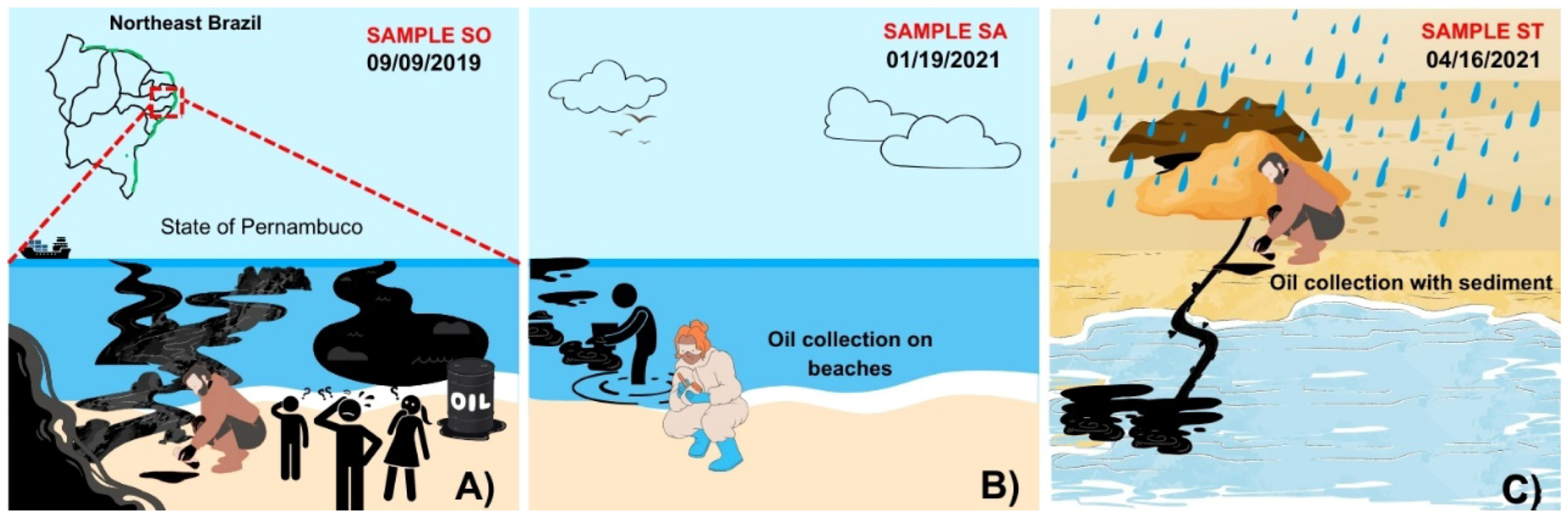

2.1. Sample Collection and Extraction

2.2. GC-MS Analysis

2.3. ESI(±) FT-ICR MS Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

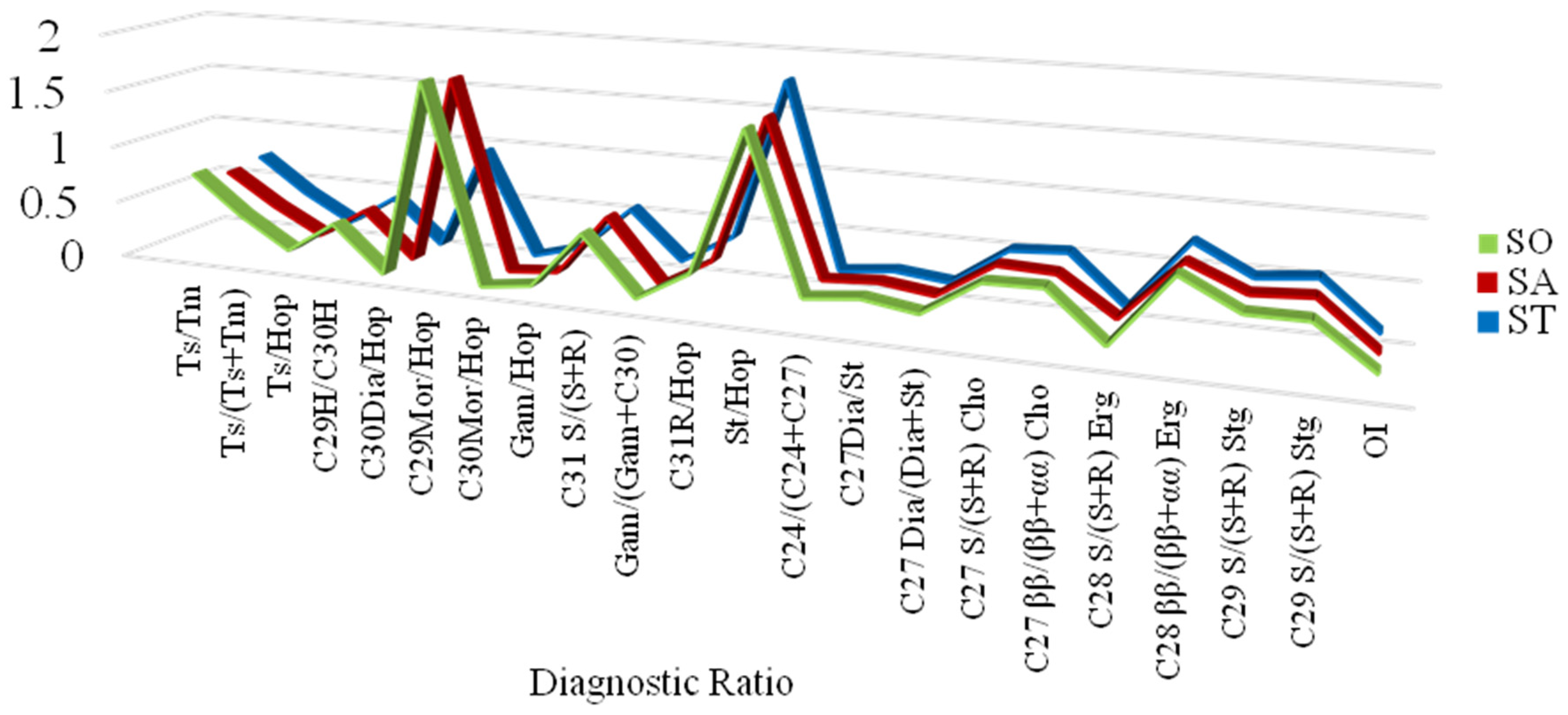

3.1. GC-MS Analysis of Non-Polar Compounds

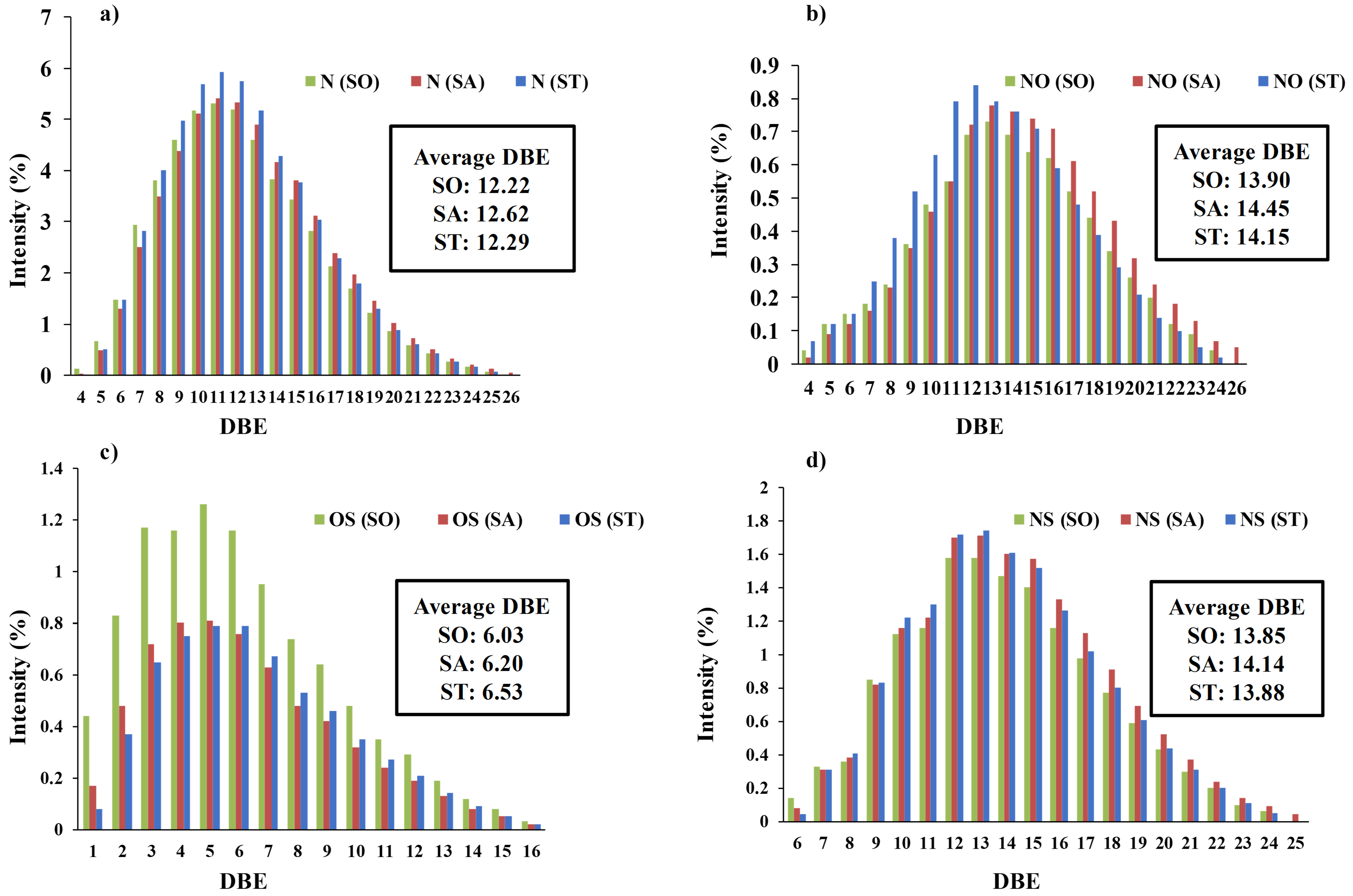

3.2. ESI(+) FT-ICR MS

3.3. ESI(−) FT-ICR MS

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pena, P.G.L.; Northcross, A.L.; de Lima, M.A.G.; de Cássia Franco Rêgo, R. The crude oil spill on the Brazilian coast in 2019: The question of public health emergency. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00231019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, R.A.; Combi, T.; Alexandre, M.; Sasaki, S.; Zanardi-Lamardo, E.; Yogui, G. Mysterious oil spill along Brazil’s northeast and southeast seaboard (2019–2020): Trying to find answers and filling data gaps. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.G.A.; Santos, I.R.; Lima, I.F.S.; Coutinho, M.E.B.; Carregosa, J.C.; Wisniewski, A.; Santos, J.M. Geochemical Assessment of Tar Balls That Arrived in 2022 along the Northeast Coast of Brazil and Their Relationship with the 2019 Oil Spill Disaster. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 16388–16395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, R.; Zanardi-Lamardo, E.; Massone, C.; Araujo, M.; Nobre, P.; Yogui, G. The mysterious oil spill in the northeastern coast of Brazil: Tracking offshore seawater and the need for improved vessel facilities. Ocean. Coast. Res. 2022, 70, e22007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, C.A.; Arey, J.S.; Graham, W.M.; Linn, J.L.; Lemkau, K.L.; Nelson, R.K.; Reddy, C.M. Floating oil-covered debris from Deepwater. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 015301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.M.; Arey, J.S.; Seewald, J.S.; Sylva, S.P.; Lemkau, K.L.; Nelson, R.K.; Carmichael, C.A.; McIntyre, C.P.; Fenwick, J.; Ventura, G.T.; et al. Composition and fate of gas and oil released to the water column during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 20229–20234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.M.; Santos, F.M.L.; Eberlin, M.N.; Wisniewski, A. Advanced Aspects of Crude Oils Correlating Data of Classical Biomarkers and Mass Spectrometry Petroleomics. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeppli, C.; Nelson, R.; Radović, J.; Carmichael, C.; Valentine, D.; Reddy, C. Recalcitrance and degradation of petroleum biomarkers upon abiotic and biotic natural weathering of Deepwater Horizon oil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 6726–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, B.D.; Martins, L.; Pereira, V.; Franco, D.; dos Santos, I.; Santos, J.; Vaz, B.; Azevedo, D.; da Cruz, G. Weathering impacts on petroleum biomarker, aromatic, and polar compounds in the spilled oil at the northeast coast of Brazil over time. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 189, 114744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, D.V.A.; Lima, G.S.; Silva, R.R.; Medeiros Júnior, I.; Gomes, A.O.; Mendes, L.A.N.; Vaz, B.G. Comprehensive composition and comparison of acidic nitrogen- and oxygen-containing compounds from pre- and post-salt Brazilian crude oil samples by ESI(−) FT-ICR MS. Fuel 2022, 326, 125129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carregosa, J.C.; Santos, I.R.D.; De Sá, M.S.; Santos, J.M.; Wisniewski, A. Multiple reaction monitoring tool applied in the geochemical investigation of a mysterious oil spill in northeast Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2021, 93, e20210171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keramea, P.; Spanoudaki, K.; Zodiatis, G.; Gikas, G.; Sylaios, G. Oil spill modeling: A critical review on current trends, perspectives, and challenges. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, I.; Lucena, P.; Moraes, A.; Carregosa, J.; Santos, T.; Wisniewski, A.; Santos, J. Biomarkers Profile of the Mysterious 2019 Oil Spill on the Northeast Coast of Brazil and Discrimination from Unreported Events. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2023, 34, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, P.; Parthipan, P.; Karthikeyan, O.P.; Rajasekar, A. Enzyme-mediated biodegradation of long-chain n-alkanes (C32 and C40) by thermophilic bacteria. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, B.D.; Martins, L.L.; de Souza, E.S.; Pudenzi, M.A.; da Cruz, G.F. Monitoring chemical compositional changes of simulated spilled Brazilian oils under tropical climate conditions by multiple analytical techniques. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 164, 111985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.; Azevedo, R.; Pereira, M.; Franco, D.; Vaz, B.; Oliveira, A.; Santos, J.; Cavalcante, R.; Martins, L. Forensic environmental geochemistry to reveal the extent, characteristics, and fate of waxy tarballs spilled over the northeast coast of Brazil in 2022. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 204, 106878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, D.; Azevedo, A.; Freitas Da Silva, T.; Bastos Da Silva, D. Avaliação geoquímica de biomarcadores ocluídos em estruturas asfaltênicas. Química Nova 2009, 32, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.E.; Walters, C.C.; Moldowan, J.M. The Biomarker Guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syakti, A.D. Molecular diagnostic ratios to assess the apportionment of petroleum hydrocarbons contaminantion in marine sediment. Molekul 2016, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, E.E.; Evans, E.D. Distribution of n-paraffins as a clue to recognition of source beds. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1961, 22, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, P.A. Organic Geochemical Proxies of Paleoceanographic, Paleolimnologic, and Paleoclimatic Processes. Org. Geochem. 1997, 27, 213–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuksezgin, F.; Pazi, I.; Gonul, L.T. Marine organic pollutants of the Eastern Aegean: Aliphatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Candarli Gulf surficial sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 2569–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, B.; Yang, J.; Sun, W.; Hou, D. Evolution characteristics of maturity-related sterane and terpane biomarker parameters during hydrothermal experiments in a semi-open system under geological constraint. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 201, 108412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Y.S.; Pereira, R.C.L.; Mendonça Filho, J.G. Geochemical characterization of lacustrine and marine oils from off-shore Brazilian sedimentary basins using negative-ion electrospray Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (ESI FTICR-MS). Org. Geochem. 2018, 124, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.; Nelson, R.; Hanke, U.; Cui, X.; Summons, R.; Valentine, D.; Rodgers, R.; Chacón-Patiño, M.; Niles, S.; Teixeira, C.; et al. Synergy of Analytical Approaches Enables a Robust Assessment of the Brazil Mystery Oil Spill. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 13688–13704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Organic Compounds in Petroleum-Contaminated Soils from the Changqing Oilfield by FT-ICR MS and GC-MS. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 18512–18520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudenzi, M.A.; Eberlin, M.N. Assessing Relative Electrospray Ionization, Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization, Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization, and Atmospheric Pressure Photo- and Chemical Ionization Efficiencies in Mass Spectrometry Petroleomic Analysis via Pools and Pairs of Selected Polar Compound Standards. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 7125–7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salata, A.B.A.d.M.; Pereira, M.G.A.; de Lima, I.F.S.; dos Santos, I.R.; Franco, D.M.M.; Vaz, B.G.; Santos, J.M. Impact of Environmental Weathering on the Chemical Composition of Spilled Oils in a Real Case in Brazil. Coasts 2025, 5, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5040049

Salata ABAdM, Pereira MGA, de Lima IFS, dos Santos IR, Franco DMM, Vaz BG, Santos JM. Impact of Environmental Weathering on the Chemical Composition of Spilled Oils in a Real Case in Brazil. Coasts. 2025; 5(4):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5040049

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalata, Ana Beatriz A. de M., Marília G. A. Pereira, Isabelle F. S. de Lima, Ignes Regina dos Santos, Danielle M. M. Franco, Boniek G. Vaz, and Jandyson M. Santos. 2025. "Impact of Environmental Weathering on the Chemical Composition of Spilled Oils in a Real Case in Brazil" Coasts 5, no. 4: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5040049

APA StyleSalata, A. B. A. d. M., Pereira, M. G. A., de Lima, I. F. S., dos Santos, I. R., Franco, D. M. M., Vaz, B. G., & Santos, J. M. (2025). Impact of Environmental Weathering on the Chemical Composition of Spilled Oils in a Real Case in Brazil. Coasts, 5(4), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5040049