Insights on Payment for Environmental Services in Fisheries: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

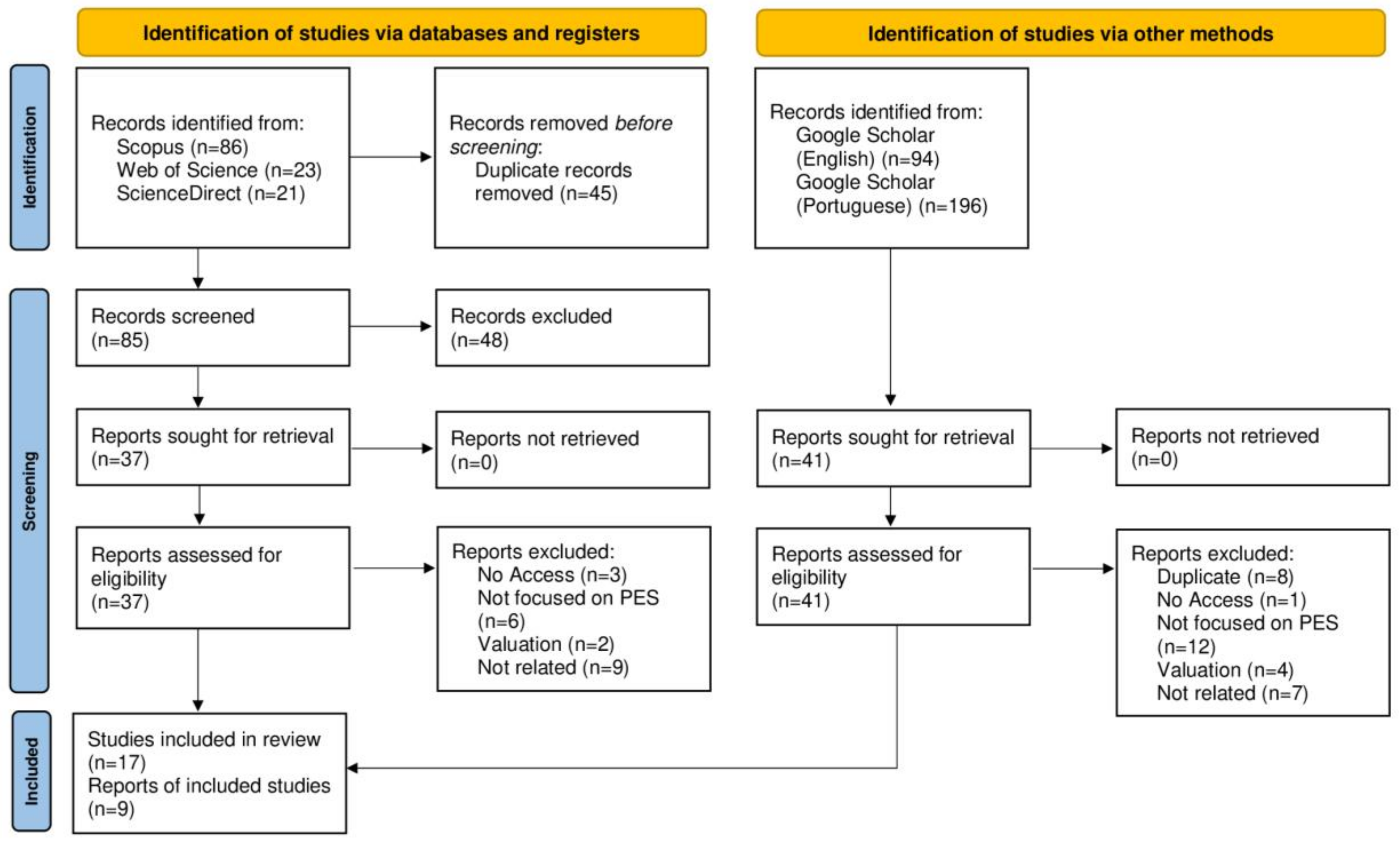

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

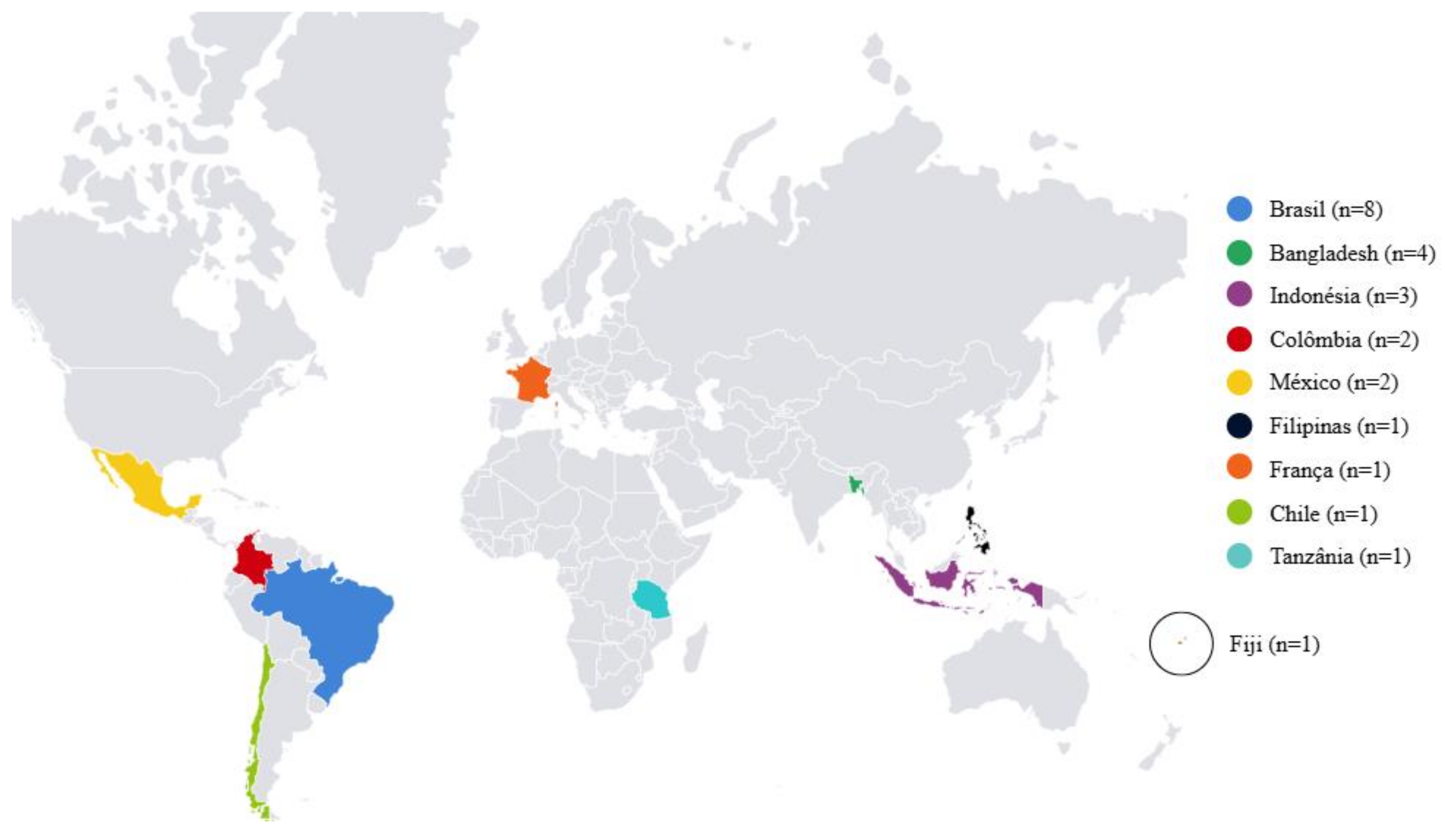

3. Results and Discussion

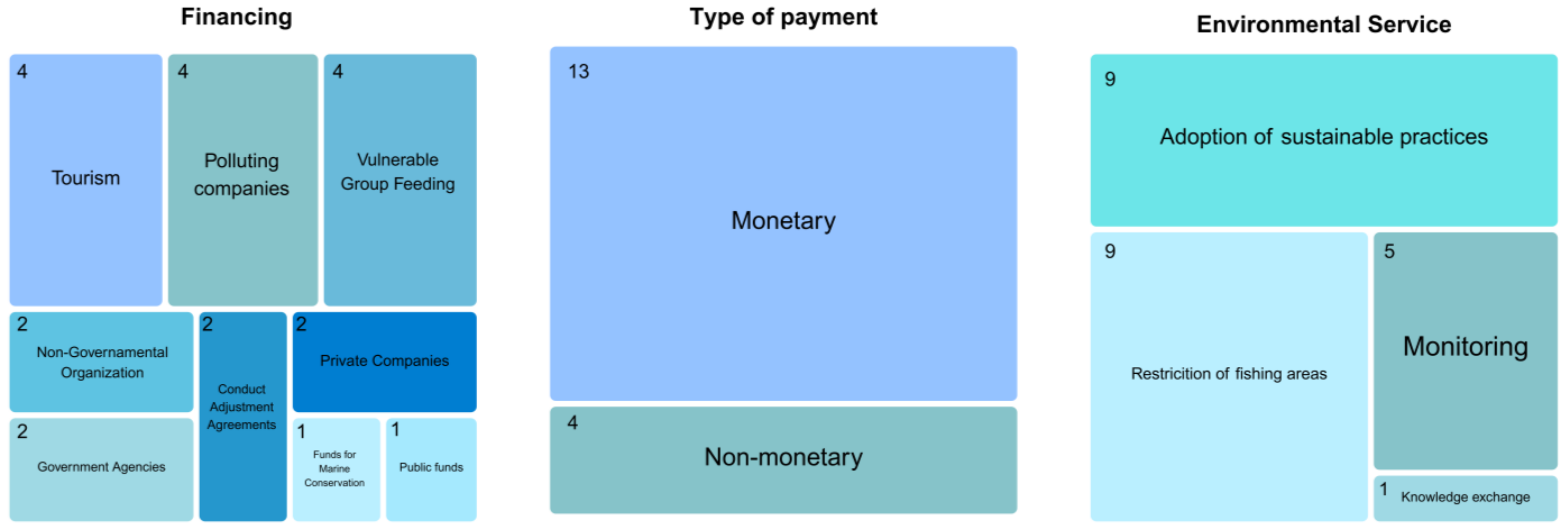

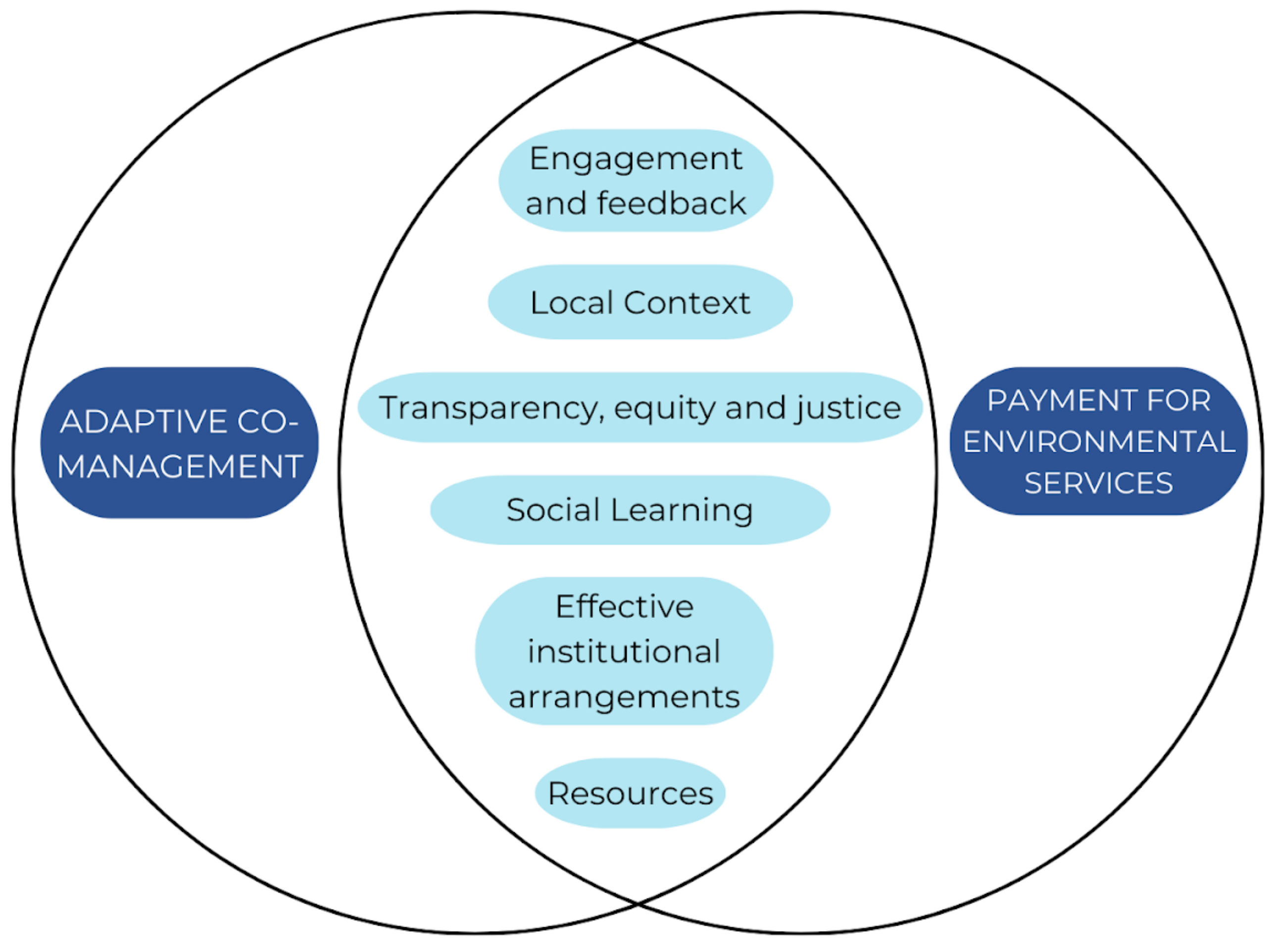

3.1. Key Elements for Marine PES

3.2. Challenges

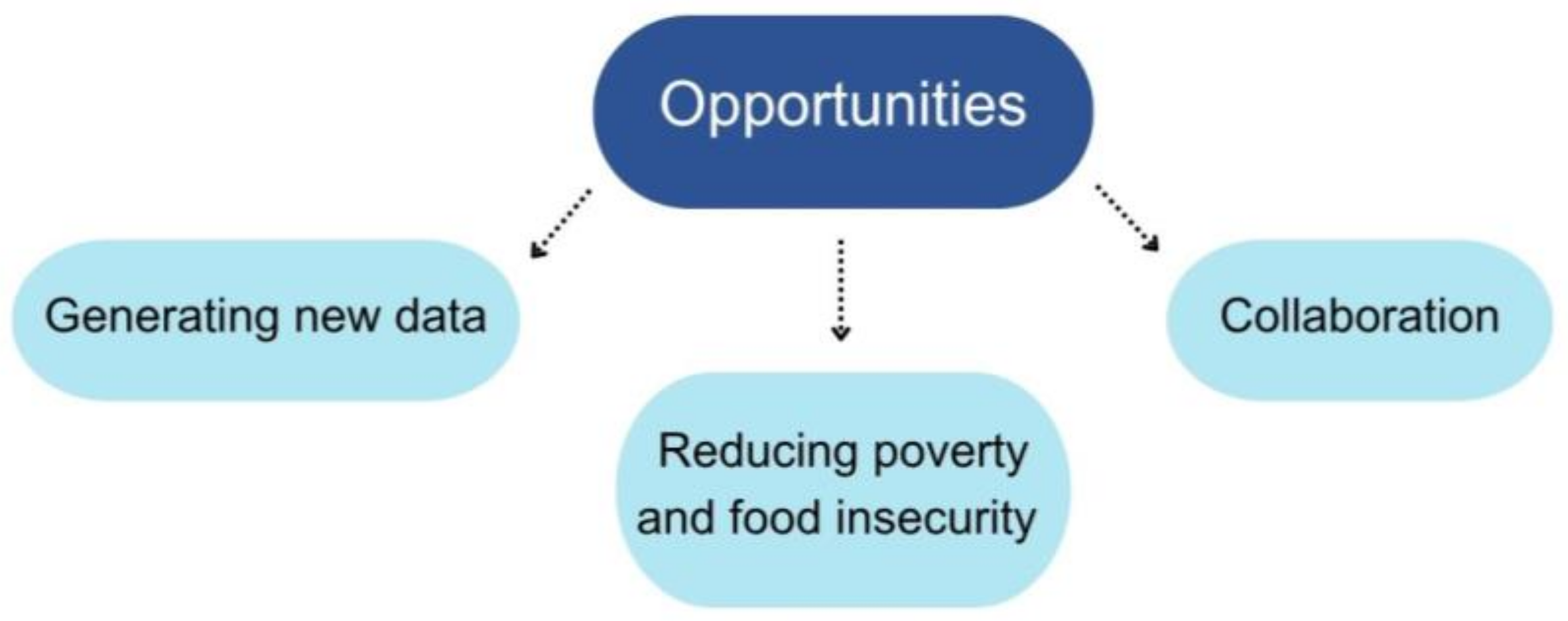

3.3. Opportunities

3.4. Lessons Learned

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PES | Payment for Environmental Services |

| REDD+ | Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| VGF | Vulnerable Group Feeding |

| WFP | World Food Program |

Appendix A

| Reference | Type | Country | Practical or Hypothetical | Financing | Calculation | Benefit | Environmental Service | Target Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [59] | Article | Mexico | Hypothetical | Tourism | Contingent Valuation | Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | - |

| [60] | Article | Tanzania | Hypothetical | - | Contingent Valuation | Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | - |

| [80] | Oral presentation abstract | Brazil | Hypothetical | Conduct Adjustment Agreements | - | - | Monitoring | Commercially important species |

| [61] | Article | Brazil | Hypothetical | Conduct Adjustment Agreements | Opportunity cost | Monetary | Monitoring | - |

| [63] | Article | Brazil | Hypothetical | - | - | Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | Commercially important species (e.g., Centropomus parallelus, Epinephelus marginatus, Scomberomorus cavalla, Lutjanus synagris) |

| [62] | Article | Brazil | Hypothetical | - | - | - | Monitoring | Species used for consumption or commerce |

| [58] | Technical Document | Bangladesh | Practical | Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) | - | Non-Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | Tenualosa ilisha |

| [83] | Article | Indonesia | Hypothetical | Tourism | Contingent Valuation | Monetary | Adoption of sustainable practices | Sphyrna spp., Rhynchobatus spp., Mobulid spp. |

| [71] | Article | Indonesia | Hypothetical | Polluting companies; Tourism; Funds for marine conservation | Contingent Valuation | Monetary and Non-Monetary | Adoption of sustainable practices | Sphyrna spp., Rhynchobatus spp. |

| [88] | Article | Indonesia | Hypothetical | Government Agencies; NGO | - | Monetary | Adoption of sustainable practices | Aprion virescens, Lutjanus vitta |

| [64] | Article | France | Hypothetical | - | - | - | Knowledge exchange with management | - |

| [65] | Article | Fiji | Hypothetical | - | - | Monetary | Restriction of fishing area; Involvement in management | - |

| [85] | Chapter | Brazil | Hypothetical | Public funds; Polluting companies | - | - | Adoption of sustainable practices; Monitoring | Arapaima gigas |

| [96] | E-book | Philippines | Practical | Private companies | - | Monetary | Adoption of sustainable practices | Octopus |

| [66] | Article | Bangladesh | Practical | Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) | - | Non-Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | Tenualosa ilisha |

| [48] | Article | Theoretical approach | ||||||

| [67] | Article | Brazil | Hypothetical | Tourism | Contingent Valuation | Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | Sharks: Carcharhinus perezi, Ginglymostoma cirratum, Negaprion brevirostris, Galeocerdo cuvier, Carcharhinus falciformis |

| [93] | Article | Colombia | Practical | NGO | Opportunity cost | Monetary and Non-Monetary | Adoption of sustainable practices | Arapaima gigas; Osteoglossum bicirrhosum |

| [49] | Article | Theoretical | ||||||

| [86] | Article | Colombia | Hypothetical | Polluting companies | Opportunity cost | Monetary | Adoption of sustainable practices | Commercially important species (e.g., Prochilodus magdalenae; Centropomus undecimalis; Mugil incilis; Megalops atlanticus) |

| [68] | Article | Bangladesh | Practical | Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) | - | Non-Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | Tenualosa ilisha |

| [89] | Chapter | Mexico | Hypothetical | Government Agencies | - | Monetary | Adoption of sustainable practices | - |

| [106] | E-book | Brazil | Practical | Private companies | - | Monetary | Adoption of sustainable practices | Commercially important species |

| [87] | Article | Brazil | Hypothetical | Polluting companies | - | - | Monitoring | Pontoporia blainvillei |

| [69] | Article | Chile | Hypothetical | - | Opportunity cost | Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | Commercially important species (e.g., Concholepas concholepas) |

| [70] | Chapter | Bangladesh | Practical | Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) | - | Non-Monetary | Restriction of fishing area | Tenualosa ilisha |

References

- FAO; Duke University. World Fish Illuminating Hidden Harvests: The Contributions of Small-Scale Fisheries to Sustainable Development; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, K.; Arnason, R.; Willmann, R. The Sunken Billions; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024: Blue Transformation in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/06690fd0-d133-424c-9673-1849e414543d (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Pikitch, E.K. The Risks of Overfishing. Science 2012, 338, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Small-Scale Fisheries Governance—A Handbook in Support of the Implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sus-tainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C. Are Fishers Poor or Vulnerable? Assessing Economic Vulnerability in Small-Scale Fishing Communities. J. Dev. Stud. 2009, 45, 911–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Restoring Unity. In World Fisheries; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, B.S.; McLeod, K.L.; Rosenberg, A.A.; Crowder, L.B. Managing for cumulative impacts in ecosystem-based management through ocean zoning. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2008, 51, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crain, C.M.; Kroeker, K.; Halpern, B.S. Interactive and cumulative effects of multiple human stressors in marine systems. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1304–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barange, M.; Merino, G.; Blanchard, J.L.; Scholtens, J.; Harle, J.; Allison, E.H.; Allen, J.I.; Holt, J.; Jennings, S. Impacts of climate change on marine ecosystem production in societies dependent on fisheries. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J. Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in the Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 873572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.R.; Gunderson, L.H. Coping with Collapse: Ecological and Social Dynamics in Ecosystem Management: Like flight simulators that train would-be aviators, simple models can be used to evoke people’s adaptive, forward-thinking behavior, aimed in this instance at sustainability of human–natural systems. BioScience 2001, 51, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Elmqvist, T.; Gunderson, L.; Holling, C.S.; Walker, B. Resilience and Sustainable Development: Building Adaptive Capacity in a World of Transformations. Ambio 2002, 31, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Rethinking Community-Based Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 15, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begossi, A. Local knowledge and training towards management. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2008, 10, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Wagner, J.R. Who Knows? On the Importance of Identifying “Experts” When Researching Local Ecological Knowledge. Hum. Ecol. 2003, 31, 463–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddle, K. Systems of Knowledge: Dialogue, Relationships and Process. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2000, 2, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.E.; Armitage, D.; Eurich, J.G.; Kleisner, K.M.; Pecl, G.T.; Tokunaga, K. Co-production of knowledge and strategies to support climate resilient fisheries. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 80, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norström, A.V.; Cvitanovic, C.; Löf, M.F.; West, S.; Wyborn, C.; Balvanera, P.; Bednarek, A.T.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; de Bremond, A.; et al. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Teh, L.; Ota, Y.; Christie, P.; Ayers, A.; Day, J.C.; Franks, P.; Gill, D.; Gruby, R.L.; Kittinger, J.N.; et al. An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation. Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallis, H.; Lubchenco, J. Working together: A call for inclusive conservation. Nature 2014, 515, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, B.K.; Kousky, C.; Sims, K.R.E. Designing payments for ecosystem services: Lessons from previous experience with incentive-based mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9465–9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Paying for Biodiversity: Enhancing the Cost-Effectiveness of Payments for Ecosystem Services; OECD: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S. Payments for Ecosystem Services: A New Way of Conserving Biodiversity in Forests. J. Sustain. For. 2009, 28, 576–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Corbera, E.; Pascual, U.; Kosoy, N.; May, P.H. Reconciling theory and practice: An alternative conceptual framework for understanding payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafton, R.Q.; Arnason, R.; Bjørndal, T.; Campbell, D.; Campbell, H.F.; Clark, C.W.; Connor, R.; Dupont, D.P.; Hannesson, R.; Hilborn, R.; et al. Incentive-based approaches to sustainable fisheries. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2006, 63, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejnowicz, A.P.; Raffaelli, D.G.; Rudd, M.A.; White, P.C.L. Evaluating the outcomes of payments for ecosystem services programmes using a capital asset framework. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 9, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landell-Mills, N.; Porras, I. Silver Bullet or Fools’ Gold: A Global Review of Markets for Forest Environmental Services and Their Impact on the Poor; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2002; Available online: https://www.iied.org/9066iied (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Ostrom, E.; Janssen, M.A.; Anderies, J.M. Going beyond panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15176–15178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Cox, M. Moving beyond panaceas: A multi-tiered diagnostic approach for social-ecological analysis. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Arsel, M.; Pellegrini, L.; Adaman, F.; Aguilar, B.; Agarwal, B.; Corbera, E.; Ezzine de Blas, D.; Farley, J.; Froger, G.; et al. Payments for ecosystem services and the fatal attraction of win-win solutions. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 6, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S. The Devil in the Detail: A Practical Guide on Designing Payments for Environmental Services. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2016, 9, 131–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Garcia, J.; Wolff, H. Payment for Ecosystem Services from Forests. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2014, 6, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamedes, I.; Guerra, A.; Rodrigues, D.B.B.; Garcia, L.C.; Godoi, R.D.F.; Oliveira, P.T.S. Brazilian payment for environmental services programs emphasize water-related services. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2023, 11, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, J.; Bennett, G.; Carroll, N.; Goldstein, A.; Jenkins, M. The global status and trends of Payments for Ecosystem Services. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Harper, R.J.; Dell, B. Examining local community understanding of mangrove carbon mitigation: A case study from Ca Mau province, Mekong River Delta, Vietnam. Mar. Policy 2023, 148, 105398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Primavera, J.H.; Friess, D.A. Governance and implementation challenges for mangrove forest Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES): Empirical evidence from the Philippines. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 23, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Friess, D.A. Stakeholder preferences for payments for ecosystem services (PES) versus other environmental management approaches for mangrove forests. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, E.; van Putten, I.; Pascoe, S.; Vieira, S. Individual transferable quotas in achieving multiple objectives of fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2020, 113, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasalla, M.A.; de Castro, F. Enhancing stewardship in Latin America and Caribbean small-scale fisheries: Challenges and opportunities. Marit. Stud. 2016, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2005; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/19193 (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Wunder, S. Revisiting the concept of payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derissen, S.; Latacz-Lohmann, U. What are PES? A review of definitions and an extension. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 6, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.; Squires, D. Reducing marine mammal bycatch in global fisheries: An economics approach. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2017, 140, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulazzani, L.; Camanzi, L.; Malorgio, G. Multifunctionality in fisheries and the provision of public goods. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 168, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanayak, S.; Wunder, S.; Ferraro, P. Show Me the Money: Do Payments Supply Environmental Services in Developing Countries? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2010, 4, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomers, S.; Matzdorf, B. Payments for ecosystem services: A review and comparison of developing and industrialized countries. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 6, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladon, A.J.; Short, K.M.; Mohammed, E.Y.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Payments for ecosystem services in developing world fisheries. Fish Fish. 2016, 17, 839–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S.; Pagiola, S.; Wunder, S. Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: An overview of the issues. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiola, S. Payments for environmental services in Costa Rica. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Albán, M. Decentralized payments for environmental services: The cases of Pimampiro and PROFAFOR in Ecuador. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhbauer, A.; Sumaila, U.R. Economic viability and small-scale fisheries—A review. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 124, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhbauer, A.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Greer, K.; Sumaila, U.R. How subsidies affect the economic viability of small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2017, 82, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladon, A.; Syed, M.; Hassan, S.M.T.; Raihan, A.T.; Uddin, M.; Ali, M.; Ali, S.; Hussein, M.; Mohammed, E.; Porras, I.; et al. Finding Evidence for the Impact of Incentive-Based Hilsa Fishery Management in Bangladesh: Combining Theory-Testing and Remote Sensing Methods; IIED: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, R.F.; Mourato, S. Investigating the potential for marine resource protection through environmental service markets: An exploratory study from La Paz, Mexico. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, R.F.; Mourato, S. Investigating fishers’ preferences for the design of marine Payments for Environmental Services schemes. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 108, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begossi, A.; May, P.H.; Lopes, P.F.; Oliveira, L.E.C.; da Vinha, V.; Silvano, R.A.M. Compensation for environmental services from artisanal fisheries in SE Brazil: Policy and technical strategies. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 71, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begossi, A. Ecological, cultural, and economic approaches to managing artisanal fisheries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2014, 16, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begossi, A.; Salivonchyk, S.; Nora, V.; Lopes, P.; Silvano, R. The Paraty artisanal fishery (southeastern Brazilian coast): Ethnoecology and management of a social-ecological system (SES). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failler, P.; Montocchio, C.; de Battisti, A.B.; Binet, T.; Maréchal, J.-P.; Thirot, M.; Failler, P.; Montocchio, C.; de Battisti, A.B.; Binet, T.; et al. Sustainable financing of marine protected areas: The case of the Martinique regional marine reserve of “Le Prêcheur”. Green Financ. 2019, 1, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurney, G.G.; Mangubhai, S.; Fox, M.; Kiatkoski Kim, M.; Agrawal, A. Equity in environmental governance: Perceived fairness of distributional justice principles in marine co-management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 124, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Mohammed, E.Y.; Ali, L. Economic incentives for sustainable hilsa fishing in Bangladesh: An analysis of the legal and institutional framework. Mar. Policy 2016, 68, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.F.M.; Villasante, S. Paying the price to solve fisheries conflicts in Brazil’s Marine Protected Areas. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, I.; Mohammed, E.Y.; Ali, L.; Ali, S.; Hossain, B. Power, profits and payments for ecosystem services in Hilsa fisheries in Bangladesh: A value chain analysis. Mar. Policy 2017, 84, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorice, M.G.; Donlan, C.J.; Boyle, K.J.; Xu, W.; Gelcich, S. Scaling participation in payments for ecosystem services programs. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.; Phillips, M.; Mohammed, E. Payments for hilsa fish (Tenualosa ilisha) conservation in Bangladesh. In Economic Incentives for Marine and Coastal Conservation: Prospects, Challenges and Policy Implications, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 170–189. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, H.; Ramdlan, M.S.; Hafizh, A.; Wongsopatty, K.; Mourato, S.; Pienkowski, T.; Adrinato, L.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Designing locally-appropriate conservation incentives for small-scale fishers. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 277, 109821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J. Watershed Development, Environmental Services, and Poverty Alleviation in India. World Dev. 2002, 30, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiola, S.; Arcenas, A.; Platais, G. Can Payments for Environmental Services Help Reduce Poverty? An Exploration of the Issues and the Evidence to Date from Latin America. World Dev. 2005, 33, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Engel, S.; Pagiola, S. Taking stock: A comparative analysis of payments for environmental services programs in developed and developing countries. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Friend, R.M. Poverty in small-scale fisheries: Old issue, new analysis. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2011, 11, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Payments for environmental services and the poor: Concepts and preliminary evidence. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2008, 13, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R.; Webster, D.G.; Cox, M.E.; Raakjær, J.; Blaxekjær, L.Ø.; Einarsson, N.; Virginia, R.A.; Acheson, J.; Bromley, D.; Cardwell, E.; et al. Moving beyond panaceas in fisheries governance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9065–9073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Agrawal, A. Understanding the Social and Ecological Outcomes of PES Projects: A Review and an Analysis. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S.; Meffe, G.K. Command and Control and the Pathology of Natural Resource Management. Conserv. Biol. 1996, 10, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begossi, A.; May, P.H.; Vinha, V. “Payments for Environmental Services: Application to Coastal Fisheries Contexts in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil”, Presented at the The Political Economy of Green Development. Available online: https://www.isecoeco.org/conferences/isee2012-versao3/pdf/sp05.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Yan, H.; Yang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, Q. Payments for ecosystem services as an essential approach to improving ecosystem services: A review. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 201, 107591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, P.; Yan, D. A PES framework coupling socioeconomic and ecosystem dynamics from a sustainable development perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 329, 117043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, H.; Mourato, S.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Investigating acceptance of marine tourism levies, to cover the opportunity costs of conservation for coastal communities. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 201, 107578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, D.; Pagiola, S. Using Contingent Valuation in the Design of Payments for Environmental Services Mechanisms: A Review and Assessment. World Bank Res. Obs. 2012, 27, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallwass, G.; Lopes, P.; Silvano, R. Could payment for environmental services reconcile fish conservation with small-scale fisheries in the Brazilian Amazon? In Economic Incentives for Marine and Coastal Conservation: Prospects, Challenges and Policy Implications; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J.L.L.; Araque, A.C. Esquema de pago por servicios ambientales como estrategia de gestión para regular la pesca artesanal del Distrito de Manejo Integrado Cispata, Colombia. Bol. Investig. Mar. Costeras 2021, 50, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.P. de Payment for Environmental Services, fishers and cetaceans’ conservation. Labor E Eng. 2013, 7, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekawaty, R.; Lynham, J.; Mous, P. Can demand-side management replicate a size limit in a small-scale fishery? Fish. Res. 2020, 223, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Planter, M.; Muñoz-Piña, C.; Oca-Leon, M.M. de Economic instruments for sustainability in Mexico’s marine protected areas and the perverse subsidy challenge. In Economic Incentives for Marine and Coastal Conservation: Prospects, Challenges and Policy Implications, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grafton, R.Q.; Hilborn, R.; Ridgeway, L.; Squires, D.; Williams, M.; Garcia, S.; Groves, T.; Joseph, J.; Kelleher, K.; Kompas, T.; et al. Positioning fisheries in a changing world. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spergel, B.; Moye, M. Financing Marine Conservation: A Menu of Options; WWF Center for Conservation Finance: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Trends, The Katoomba Group; UNEP. Payments for Ecosystem Services: Getting Started in Marine and Coastal Ecosystems: A Primer; Forest Trends and The Katoomba Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.forest-trends.org/publications/payments-for-ecosystem-services-getting-started-in-marine-and-coastal-ecosystems/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Mora, M.; Palacios, E.; Niesten, E. Assessing the impact of conservation agreements on threatened fish species: A case study in the Colombian Amazon. Oryx 2018, 52, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. The efficiency of payments for environmental services in tropical conservation. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uraguchi, Z.B. Payments for marine ecosystem services and food security: Lessons from income transfer programmes. In Economic Incentives for Marine and Coastal Conservation: Prospects, Challenges and Policy Implications, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, V.; Mathias, K.; Meyers, D.; Victurine, R.; Walsh, M. Finance Tools for Coral Reef Conservation: A Guide; Wildlife Conservation Society: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://icriforum.org/finance-tools-for-coral-reef-conservation-a-guide/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Diegues, A.C. O Mito Moderno da Natureza Intocada, 6th ed.; Hucitec; NUPAUB/USP: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, M.M.; Timóteo, G.M.; Arruda, A.P.S.N. de A dinâmica da pesca artesanal na Bacia de Campos: Organização social e práticas em economia solidária entre os pescadores artesanais. Rev. Crítica Ciênc. Sociais 2018, 116, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvitanovic, C.; Shellock, R.J.; Mackay, M.; van Putten, E.I.; Karcher, D.B.; Dickey-Collas, M.; Ballesteros, M. Strategies for building and managing ‘trust’ to enable knowledge exchange at the interface of environmental science and policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 123, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C.; Fazey, I.; Evely, A.C.; Kruijsen, J.H.J. Five principles for the practice of knowledge exchange in environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, C.; Villasante, S.; Pascual-Fernández, J.J. Managing small-scale fisheries under data poor scenarios: Lessons from around the world. Mar. Policy 2019, 101, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemmel, E.; Friedlander, A.; Andrade, P.; Castro, L.; Wiggins, C.; Wilcox, B.; Yasutake, Y.; Schemmel, E.; Friedlander, A.; Andrade, P.; et al. The codevelopment of coastal fisheries monitoring methods to support local management. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, J.; Baylis, K.; Corbera, E.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Honey-Rosés, J.; Persson, U.M.; Wunder, S. The Effectiveness of Payments for Environmental Services. World Dev. 2017, 96, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Muradian, R.; Brander, L.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Martín-López, B.; Verma, M.; Armsworth, P.; Christie, M.; Cornelissen, J.; Eppink, F.; et al. The Economics of Valuing Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity. In The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seehusen, S.; Hercowitz, M.; Figueiredo, G.; Romeiro, A.; Uezu, A.; Tafuri, A.; Menezes da Silva, C.; Kuklinski, C.; Klemz, C.; Moreira, G.; et al. Lições Aprendidas na Conservação e Recuperação da Mata Atlântica: Sistematização de Desafios e Melhores Práticas dos Projetos-Pilotos de Pagamentos por Serviços Ambientais; MMA: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- de Vente, J.; Reed, M.; Stringer, L.; Valente, S.; Newig, J. How does the context and design of participatory decision making processes affect their outcomes? Evidence from sustainable land management in global drylands. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, I.M.; McCay, B.J. Cooperative research, co-management and the social dimension of fisheries science and management. Mar. Policy 2004, 28, 257–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; Berkes, F.; Doubleday, N. Adaptive Co-Management: Collaboration, Learning, and Multi-Level Governance; University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Hahn, T. Social-Ecological Transformation for Ecosystem Management: The Development of Adaptive Co-Management of a Wetland Landscape in Southern Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Hashimoto, A. Adaptive Co-Management and the Need for Situated Thinking in Collaborative Conservation. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2011, 16, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Fitzgibbon, J. Co-management of Natural Resources: A Proposed Framework. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A. An institutional analysis of payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Develey, L.; Gonçalves, L.R. Insights on Payment for Environmental Services in Fisheries: A Systematic Review. Coasts 2025, 5, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5020020

Develey L, Gonçalves LR. Insights on Payment for Environmental Services in Fisheries: A Systematic Review. Coasts. 2025; 5(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeveley, Laura, and Leandra Regina Gonçalves. 2025. "Insights on Payment for Environmental Services in Fisheries: A Systematic Review" Coasts 5, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5020020

APA StyleDeveley, L., & Gonçalves, L. R. (2025). Insights on Payment for Environmental Services in Fisheries: A Systematic Review. Coasts, 5(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts5020020