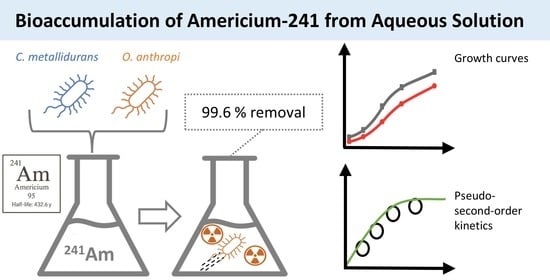

Exploring the Potential of Cupriavidus metallidurans and Ochrobactrum anthropi for 241Am Bioaccumulation in Aqueous Solution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria Preparation

2.2. Americium Uptake Experiments

2.3. Americium Removal and Kinetics

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preliminary Experiments

3.2. Uptake of 241Am by Bacteria

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PFO | Pseudo-first-order |

| PSO | Pseudo-second-order |

| RND | Resistance-nodulation-division |

| MIC | Minimal inhibitory concentration |

| TSM | Tris Salt Medium |

| OD | Optical density |

| LD-50 | Lethal dose for 50% |

References

- Taylor, D. Gut Transfer of Environmental Plutonium and Americium. Lancet 1986, 327, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckerman, K.; Harrison, J.; Menzel, H.-G. Compendium of Dose Coefficients Based on ICRP Publication 60; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4557-5430-4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Luo, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jin, J.; Liao, J. Biosorption of Americium-241 by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2002, 252, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). National Primary Drinking Water Regulations; Radionuclides; Final Rule. Fed. Regist. 2000, 65, 76708. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Attar, L.; Dyer, A.; Harjula, R. Uptake of Radionuclides on Microporous and Layered Ion Exchange Materials. J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Conesa, S.; Martínez, J.M.; Pappalardo, R.R.; Sánchez Marcos, E. Extracting the Americyl Hydration from an Americium Cationic Mixture in Solution: A Combined X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy and Molecular Dynamics Study. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 8089–8097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegl, T.; Košak, A.; Lobnik, A.; Novak, Z.; Kralj, A.K.; Ban, I. Adsorption of Rare Earth Metals from Wastewater by Nanomaterials: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 386, 121632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deblonde, G.J.-P.; Mattocks, J.A.; Wang, H.; Gale, E.M.; Kersting, A.B.; Zavarin, M.; Cotruvo, J.A. Characterization of Americium and Curium Complexes with the Protein Lanmodulin: A Potential Macromolecular Mechanism for Actinide Mobility in the Environment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 15769–15783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volesky, B. Detoxification of Metal-Bearing Effluents: Biosorption for the next Century. Hydrometallurgy 2001, 59, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmak, K.N.; Despotopulos, J.D.; Huynh, T.L.; Kerlin, W.M. TALSPEAK-Based Separation of the Trivalent Actinides from Rare Earth Elements Using LN Resin. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2025, 334, 2407–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesar, F.; Van Hecke, K.; Zsabka, P.; Verguts, K.; Binnemans, K.; Cardinaels, T. Separation of Americium from Highly Active Raffinates by an Innovative Variant of the AmSel Process Based on the Ionic Liquid Aliquat-336 Nitrate. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 36322–36336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidanov, V.L.; Shadrin, A.Y.; Tkachenko, L.I.; Kenf, E.V.; Parabin, P.V.; Shirokov, S.S. Separation of Americium and Curium for Transmutation in the Fast Neutron Reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2021, 385, 111434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincher, B.J.; Law, J.D.; Goff, G.S.; Moyer, B.A.; Burns, J.D.; Lumetta, G.J.; Sinkov, S.I.; Shehee, T.C.; Hobbs, D.T. Higher Americium Oxidation State Research Roadmap; Idaho National Lab. (INL): Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, A.Y.; Uslu, G.; Tepe, O.; Cuci, Y.; Ekiz, H.I. A Comparative Investigation on the Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metal Ions by Growing Rhizopus arrhizus and Aspergillus niger. Biochem. Eng. J. 2003, 15, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaduková, J.; Virčíková, E. Comparison of Differences between Copper Bioaccumulation and Biosorption. Environ. Int. 2005, 31, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saraj, M.; Abdel-Latif, M.S.; El-Nahal, I.; Baraka, R. Bioaccumulation of Some Hazardous Metals by Sol–Gel Entrapped Microorganisms. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1999, 248, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, L.; Dussan, J. Biosorption and Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals on Dead and Living Biomass of Bacillus sphaericus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 167, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayele, A.; Haile, S.; Alemu, D.; Kamaraj, M. Comparative Utilization of Dead and Live Fungal Biomass for the Removal of Heavy Metal: A Concise Review. Sci. World J. 2021, 5588111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, O.; Plöhn, M.; Funk, C. The Cell Wall of Green Microalgae and Its Role in Heavy Metal Removal. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-S.; Law, R.; Chang, C.-C. Biosorption of Lead, Copper and Cadmium by Biomass of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PU21. Water Res. 1997, 31, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hua, S.; Xia, F.; Hu, B. Efficient Extraction of Radionuclides with MXenes/Persimmon Tannin Functionalized Cellulose Nanofibers: Performance and Mechanism. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 609, 155254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, I.; Pashalidis, I.; Raptopoulos, G.; Paraskevopoulou, P. Radioactivity/Radionuclide (U-232 and Am-241) Removal from Waters by Polyurea-Crosslinked Alginate Aerogels in the Sub-Picomolar Concentration Range. Gels 2023, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, L.G.; de Borba, T.R.; de Pádua Ferreira, R.V.; Canevesi, R.L.S.; da Silva, E.A.; Dellamano, J.C.; Marumo, J.T.; Araujo, L.G.d.; Borba, T.R.d.; Ferreira, R.V.d.P.; et al. Use of Calcium Alginate Beads and Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Biosorption of 241Am. J. Environ. Radioact. 2020, 223–224, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dong, F.; Dai, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Transformation of Radionuclide Occurrence State in Uranium and Strontium Recycling by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2022, 331, 2621–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupian, M.; Rosskopfová, O.; Viglašová, E.; Vyhnáleková, S.; Daňo, M.; Švajdlenková, H.; Galamboš, M. Investigation of the Adsorptive Properties of Filamentous Fungus Aspergillus niger in the Removal of 85Sr and 99mTc from Aqueous Solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2025, 334, 6849–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, F.; Song, W.; Sun, Y. Bioaccumulation of Uranium by Candida Utilis: Investigated by Water Chemistry and Biological Effects. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monchy, S.; Benotmane, M.A.; Janssen, P.; Vallaeys, T.; Taghavi, S.; van der Lelie, D.; Mergeay, M. Plasmids pMOL28 and pMOL30 of Cupriavidus metallidurans Are Specialized in the Maximal Viable Response to Heavy Metals. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 7417–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P.J.; Van Houdt, R.; Moors, H.; Monsieurs, P.; Morin, N.; Michaux, A.; Benotmane, M.A.; Leys, N.; Vallaeys, T.; Lapidus, A.; et al. The Complete Genome Sequence of Cupriavidus metallidurans Strain CH34, a Master Survivalist in Harsh and Anthropogenic Environments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Rozycki, T.; Nies, D.H. Cupriavidus metallidurans: Evolution of a Metal-Resistant Bacterium. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2009, 96, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millacura, F.A.; Janssen, P.J.; Monsieurs, P.; Janssen, A.; Provoost, A.; Van Houdt, R.; Rojas, L.A. Unintentional Genomic Changes Endow Cupriavidus metallidurans with an Augmented Heavy-Metal Resistance. Genes 2018, 9, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Große, C.; Kohl, T.A.; Niemann, S.; Herzberg, M.; Nies, D.H. Loss of Mobile Genomic Islands in Metal-Resistant, Hydrogen-Oxidizing Cupriavidus metallidurans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e02048-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, M.; Bauer, L.; Kirsten, A.; Nies, D.H. Interplay between Seven Secondary Metal Uptake Systems Is Required for Full Metal Resistance of Cupriavidus metallidurans. Metallomics 2016, 8, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colliard, I.; Deblonde, G.J.-P. Polyoxometalate Ligands Reveal Different Coordination Chemistries Among Lanthanides and Heavy Actinides. JACS Au 2024, 4, 2503–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Feng, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, F.; Ke, W.; Huang, Y.; Wu, C.; Xu, X.; Guo, J.; Xue, S. Organic Acid Release and Microbial Community Assembly Driven by Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria Enhance Pb, Cd, and As Immobilization in Soils Remediated with Iron-Doped Hydroxyapatite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 488, 137340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Liu, X.; Sun, P.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Hong, M.; Mao, Z.-W.; Zhao, J. Simple Whole-Cell Biodetection and Bioremediation of Heavy Metals Based on an Engineered Lead-Specific Operon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 3363–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Castillo, A.M.; Monges-Rojas, T.L.; Rojas-Avelizapa, N.G. Specificity of Mo and V Removal from a Spent Catalyst by Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Provoost, A.; Maertens, L.; Leys, N.; Monsieurs, P.; Charlier, D.; Houdt, R.V. Genomic and Transcriptomic Changes That Mediate Increased Platinum Resistance in Cupriavidus metallidurans. Genes 2019, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bütof, L.; Große, C.; Lilie, H.; Herzberg, M.; Nies, D.H. Interplay between the Zur Regulon Components and Metal Resistance in Cupriavidus metallidurans. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00192-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millacura, F.A.; Cardenas, F.; Mendez, V.; Seeger, M.; Rojas, L.A. Degradation of Benzene by the Heavy-Metal Resistant Bacterium Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 Reveals Its Catabolic Potential for Aromatic Compounds. bioRxiv 2017, 164517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, S.; Rehman, A.; Qazi, M.H. Swimming, Swarming, Twitching, and Chemotactic Responses of Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 and Pseudomonas putida Mt2 in the Presence of Cadmium. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 66, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorens, I.; Untereiner, G.; Jaillard, D.; Gouget, B.; Chapon, V.; Carriere, M. Uranium Interaction with Two Multi-Resistant Environmental Bacteria: Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 and Rhodopseudomonas palustris. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleem, M.N.; Ali, M.; Boyle, S.M.; Mukhopadhyay, B.; Witonsky, S.G.; Schurig, G.G.; Sriranganathan, N. Establishment of a Gene Expression System in Ochrobactrum anthropi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 6833–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, G.; Ozturk, T.; Ceyhan, N.; Isler, R.; Cosar, T. Heavy Metal Biosorption by Biomass of Ochrobactrum anthropi Producing Exopolysaccharide in Activated Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 90, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yan, F.; Huang, F.; Chu, W.; Pan, D.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, J.; Yu, M.; Lin, Z.; Wu, Z. Bioremediation of Cr (VI) and Immobilization as Cr (III) by Ochrobactrum anthropi. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 6357–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Pan, D.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, X.; Huang, F.; Lin, Z. Microscopic Investigations of the Cr(VI) Uptake Mechanism of Living Ochrobactrum anthropi. Langmuir 2008, 24, 9630–9635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pádua Ferreira, R.V.; Sakata, S.K.; Isiki, V.L.K.; Miyamoto, H.; Bellini, M.H.; de Lima, L.F.C.P.; Marumo, J.T. Influence of Americium-241 on the Microbial Population and Biodegradation of Organic Waste. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2011, 9, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, S.H.; Herzberg, M.; Ben Fekih, I.; Zhang, C.; Bello, S.K.; Li, Y.P.; Su, J.; Xu, J.; Feng, R.; Zhou, S.; et al. Comparative Insights into the Complete Genome Sequence of Highly Metal Resistant Cupriavidus metallidurans Strain BS1 Isolated from a Gold–Copper Mine. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maertens, L.; Leys, N.; Matroule, J.-Y.; Van Houdt, R. The Transcriptomic Landscape of Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 Acutely Exposed to Copper. Genes 2020, 11, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.; Lesaulnier, C.; Monchy, S.; Wattiez, R.; Mergeay, M.; Van Der Lelie, D. Lead(II) Resistance in Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34: Interplay between Plasmid and Chromosomally-Located Functions. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2009, 96, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogiers, T.; Merroun, M.L.; Williamson, A.; Leys, N.; Houdt, R.V.; Boon, N.; Mijnendonckx, K. Cupriavidus metallidurans NA4 Actively Forms Polyhydroxybutyrate-Associated Uranium-Phosphate Precipitates. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alviz-Gazitua, P.; Durán, R.E.; Millacura, F.A.; Cárdenas, F.; Rojas, L.A.; Seeger, M. Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 Possesses Aromatic Catabolic Versatility and Degrades Benzene in the Presence of Mercury and Cadmium. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Große, C.; Scherer, J.; Schleuder, G.; Nies, D.H. Interplay between Two-Component Regulatory Systems Is Involved in Control of Cupriavidus metallidurans Metal Resistance Genes. J. Bacteriol. 2023, 205, e00343-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Yuan, M.; Zeng, Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhan, W.; Chen, H.; Mao, Z.; Wang, Y. Efficient Reduction of Reactive Black 5 and Cr(VI) by a Newly Isolated Bacterium of Ochrobactrum anthropi. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 406, 124641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrasa, E.; Palet, C.; López-Gómez, I.; Gutiérrez, D.; Esteve, I.; Sánchez-Chardi, A.; Solé, A. Cellular Strategies against Metal Exposure and Metal Localization Patterns Linked to Phosphorus Pathways in Ochrobactrum anthropi DE2010. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, M.P.; Mulla, S.I.; Ninnekar, H.Z. Biodegradation of Organophosphate Pesticide Quinalphos by Ochrobactrum sp. Strain HZM. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinanti, A.; Nainggolan, I.J. Petroleum Residues Degradation in Laboratory-Scale by Rhizosphere Bacteria Isolated from the Mangrove Ecosystem. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 106, 012100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergeay, M.; Nies, D.; Schlegel, H.G.; Gerits, J.; Charles, P.; Van Gijsegem, F. Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 Is a Facultative Chemolithotroph with Plasmid-Bound Resistance to Heavy Metals. J. Bacteriol. 1985, 162, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI. Metodologia Dos Testes de Sensibilidade a Agentes Antimicrobianos Por Diluição Para Bactéria de Crescimento Aeróbico: Norma Aprovada-Sexta Edição; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2003; Volume 23, ISBN 1-56238-486-4. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski, M.; Lucchini, J.-F.; Richmann, M.; Reed, D. Actinide (III) Solubility in WIPP Brine: Data Summary and Recommendations (No. LA-14360); Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL): Los Alamos, NM, USA, 2009; p. 966984. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, S. Analysis of Americium, Plutonium and Technetium Solubility in Groundwater; Japan Atomic Energy Research Inst.: Tokyo, Japan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, M.T.; Martinko, J.M.; Bender, K.S.; Buckley, D.H.; Stahl, D.A. Microbiologia de Brock-14a Edição; Artmed Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2016; ISBN 85-8271-298-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jepras, R.I.; Carter, J.; Pearson, S.C.; Paul, F.E.; Wilkinson, M.J. Development of a Robust Flow Cytometric Assay for Determining Numbers of Viable Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 2696–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrier, T.; Martin-Garin, A.; Morello, M. Am-241 Remobilization in a Calcareous Soil under Simplified Rhizospheric Conditions Studied by Column Experiments. J. Environ. Radioact. 2005, 79, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S.; Lagergren, S.; Lagergren, S.Y.; Sven, K. Zur Theorie der Sogenannten Adsorption Gelöster Stoffe. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1898, 24, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-Second Order Model for Sorption Processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Usuda, S. Applicability of Insoluble Tannin to Treatment of Waste Containing Americium. J. Alloys Compd. 1998, 271, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Kedari, C.S.; Shinde, S.S.; Ghosh, S.; Jambunathan, U. Performance of Immobilized Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the Removal of Long Lived Radionuclides from Aqueous Nitrate Solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2002, 253, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, P.S.; Kannan, R.; Naik, P.W.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Ramanujam, A.; Salvi, N.A. Biosorption of Americium Using Biomasses of Various Rhizopus Species. Biotechnol. Lett. 2002, 24, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Yang, Y.; Luo, S.; Liu, N.; Jin, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, P. Biosorption of Americium-241 by Immobilized Rhizopus arrihizus. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2004, 60, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.S.; Liu, N.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jin, J.; Liao, J. Biosorption of Americium-241 by Candida sp. Radiochim. Acta 2003, 91, 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka, Y.; Saito, T.; Nagasaki, S.; Tanaka, S.; Kozai, N.; Ohnuki, T. Metal Sorption to Pseudomonas Fluorescens: Influence of pH, Ionic Strength and Metal Concentrations. Geomicrobiol. J. 2007, 24, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk’yanova, E.A.; Zakharova, E.V.; Konstantinova, L.I.; Nazina, T.N. Sorption of Radionuclides by Microorganisms from a Deep Repository of Liquid Low-Level Waste. Radiochemistry 2008, 50, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, P.; Teyssié, J.-L.; Fowler, S.W.; Warnau, M. Assessment of the Exposure Pathway in the Uptake and Distribution of Americium and Cesium in Cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) at Different Stages of Its Life Cycle. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2006, 331, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsunovsky, A.; Zotina, T.; Bondareva, L. Accumulation and Release of 241Am by a Macrophyte of the Yenisei River (Elodea canadensis). J. Environ. Radioact. 2005, 81, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffree, R.A.; Markich, S.J.; Oberhaensli, F.; Teyssie, J.-L. Biokinetics of Americium-241 in the Euryhaline Diamond Sturgeon Acipenser gueldenstaedtii Following Its Uptake from Water or Food. J. Environ. Radioact. 2024, 278, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, I.; Xenofontos, A.; Anastopoulos, I.; Pashalidis, I. Americium Sorption by Microplastics in Aqueous Solutions. Coatings 2022, 12, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavaddod, S.; Dawson, A.; Allen, R.J. Bacterial Aggregation Triggered by Low-Level Antibiotic-Mediated Lysis. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Luo, W.; Liu, H. A Prediction Model for CO2/CO Adsorption Performance on Binary Alloys Based on Machine Learning. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 12235–12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Activity Concentration (Bq mL−1) | Bacteria | |

|---|---|---|

| C. metallidurans | O. anthropi | |

| 40 | + | + |

| 80 | + | + |

| 120 | + | + |

| 150 | + | + |

| 200 | + | + |

| 250 | + | + |

| 300 | + | + |

| 350 | + | + |

| 400 | + | + |

| 500 | - | + |

| 700 | - | + |

| 800 | - | + |

| 900 | - | + |

| 1000 | - | + |

| 1200 | - | + |

| 1400 | - | - |

| Biomaterial | Adsorption Type | qmax or qeq (mmol g−1) | R (%) | Contact Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tannin | Biosorption | 7 × 10−3 | - | ~200 min | [66] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Biosorption | - | 95 | 60 min | [67] |

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Biosorption | - | 99 | 60 min | [3] |

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Biosorption | - | [68] | ||

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Biosorption | - | 97 | 120 min | [69] |

| Candida sp. | Biosorption | - | 98 | 240 min | [70] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Biosorption | - | 100 | - | [71] |

| Pseudomonas | Biosorption | - | 72 | - | [72] |

| Bacteria communities | Bioaccumulation | 1.1 × 10−9 5.4 × 10−10 5.4 × 10−10 | - | - | [46] |

| Sepia officinalis (cuttlefish) | Bioaccumulation | - | 65 | - | [73] |

| Elodea canadensis | Bioaccumulation | 2.6 × 10−5 * | - | - | [74] |

| Acipenser gueldenstaedtii (diamond sturgeon) | Bioaccumulation | - | 50 | 14–28 days | [75] |

| O. anthropi | Bioaccumulation | 1.47 × 10−8 | 95 | 2 min | This study |

| C. metallidurans | Bioaccumulation | - | 99.6 | 360 min | This study |

| PFO | PSO | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | pH | C0 | qeq,exp · 10−10 | k1 | qeq,calc · 10−10 | R2 | k2 × 102 | qeq,calc · 10−10 | R2 |

| (Bq mL−1) | (mmol g−1) | (h−1) | (mmol g−1) | (g mmol−1 h−1) | (mmol g−1) | ||||

| O. anthropi | 7 | 75 | 34.93 | 119.76 | 34.64 | 0.996 | 3.04 | 34.73 | 0.997 |

| 7 | 150 | 66.20 | 136.19 | 70.15 | 0.991 | 1.39 | 70.68 | 0.992 | |

| 7 | 300 | 139.74 | 466.16 | 143.33 | 0.997 | 0.42 | 144.48 | 0.998 | |

| C. metallidurans | 5 | 75 | 36.73 | 2.22 | 35.41 | 0.986 | 0.16 | 36.67 | 0.994 |

| 5 | 150 | 72.88 | 3.41 | 70.94 | 0.996 | 0.29 | 71.69 | 0.996 | |

| 5 | 300 | 146.94 | 2.43 | 144.30 | 0.998 | 0.06 | 147.26 | 1.000 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Araujo, L.G.; de Borba, T.R.; Canevesi, R.L.S.; Guilhen, S.N.; da Silva, E.A.; Marumo, J.T. Exploring the Potential of Cupriavidus metallidurans and Ochrobactrum anthropi for 241Am Bioaccumulation in Aqueous Solution. AppliedChem 2025, 5, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem5040034

de Araujo LG, de Borba TR, Canevesi RLS, Guilhen SN, da Silva EA, Marumo JT. Exploring the Potential of Cupriavidus metallidurans and Ochrobactrum anthropi for 241Am Bioaccumulation in Aqueous Solution. AppliedChem. 2025; 5(4):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem5040034

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Araujo, Leandro Goulart, Tania Regina de Borba, Rafael Luan Sehn Canevesi, Sabine Neusatz Guilhen, Edson Antonio da Silva, and Júlio Takehiro Marumo. 2025. "Exploring the Potential of Cupriavidus metallidurans and Ochrobactrum anthropi for 241Am Bioaccumulation in Aqueous Solution" AppliedChem 5, no. 4: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem5040034

APA Stylede Araujo, L. G., de Borba, T. R., Canevesi, R. L. S., Guilhen, S. N., da Silva, E. A., & Marumo, J. T. (2025). Exploring the Potential of Cupriavidus metallidurans and Ochrobactrum anthropi for 241Am Bioaccumulation in Aqueous Solution. AppliedChem, 5(4), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem5040034