2. Materials and Methods

The dataset was constructed using DrugBank [

38] and ClassyFire [

39]. A custom Python 3.11 parser employing the BeautifulSoup [

40] and requests [

41] libraries was developed to extract chemical structures (SMILES) and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification data from DrugBank. The extracted records were stored in an SQLite database.

In total, 17,287 DrugBank entries were retrieved, of which 3403 compounds had ATC annotations. From these, 46 substances labeled under ATC code A10 (antidiabetic agents) were selected as the positive class (label = 1,

Table 1), while 2883 compounds from other ATC categories with valid annotations formed the negative class (label = −1).

To generate structural descriptors, the ClassyFire tool was employed. It assigned hierarchical taxonomic classes to each compound based on molecular structure, linking DrugBank IDs with ChemOnt and ChEBI classifications [

39]. This yielded categorical descriptors reflecting structural and chemical properties.

In parallel, numerical descriptors were computed using the Mordred library [

42], generating over 1800 features per compound, including topological, physicochemical, and geometric parameters. Three-dimensional structures were prepared using Open Babel for SMILES conversion and optimized via the PM6 method in Gaussian 16 [

43].

To address class imbalance, SMOTE [

44] was applied to the training and test sets, excluding the validation set. For Mordred descriptors, the dataset (45 active, 2461 inactive; active class defined in

Table 1) was partitioned into: validation (14 active, 738 inactive), test (9 active, 518 inactive) and SMOTE-balanced training (1205 active/inactive). For ClassyFire descriptors (46 active, 2883 inactive), the splits were: validation (14 active, 865 inactive), test (9 active, 606 inactive) and SMOTE-balanced training (1412 active/inactive)

Thirteen classification algorithms from scikit-learn [

45,

46] were employed, covering a range of approaches: linear models (Logistic Regression, Ridge Regression, Lasso Regression, Elastic Net), probabilistic models (Bernoulli Naive Bayes, Multinomial Naive Bayes), tree-based methods (Decision Tree, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting), and other classifiers (k-Nearest Neighbors, Linear Discriminant Analysis, Linear SVM, SGDClassifier). All models were trained using 12-fold stratified cross-validation and evaluated by Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1 Score, Balanced Accuracy, ROC AUC, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), ensuring robustness for imbalanced classification tasks. The models were implemented with the following parameter settings: Logistic Regression with solver = ‘liblinear’, BernoulliNB with default settings, Multinomial Naive Bayes wrapped in a MinMaxScaler(), Linear SVM, k-NN, Random Forest, LDA, and SGD Classifier with default configurations, Lasso Regression using penalty = ‘l1’ and solver = ‘saga’, Ridge Regression with alpha = 1.0 and solver = ‘auto’, Elastic Net with penalty = ‘elasticnet’, l1_ratio = 0.5, and solver = ‘saga’, Decision Tree using criterion = ‘gini’ and max_depth = None, and Gradient Boosting with n_estimators = 100 and learning_rate = 0.1. At this stage of the study, hyperparameter tuning was not conducted; default or representative configurations were applied to allow for consistent baseline comparison across all models.

To compare group differences in the distribution of molecular descriptors between compound classes, Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) test was applied. For each descriptor, a 2 × 2 contingency table was constructed to compare the frequency of presence/absence of the descriptor (non-zero values) between the two study groups (y = 1 and y = -1). Differences were considered statistically significant when the corrected p-value (q-value) was less than 0.05.

All data used in this study are publicly available and can be accessed, reproduced, and reused from the GitHub repository

https://github.com/pruhlo/appliedchem-3624702 (accessed on 9 July 2025). The repository contains raw and processed data for both antidiabetic and non-antidiabetic compounds, including molecular structures in SMILES and 3D formats, descriptor matrices in CSV and Pickle formats (Mordred and ClassyFire), annotated ontological classifications, trained machine learning models (in .pkl and .pt formats), and evaluation metrics such as feature importance and confusion matrices. Additionally, executable Jupyter notebooks are provided to reproduce descriptor generation, 3D structure conversion, classification modeling, and SMILES generation using RNNs. Visualization files and system requirements are also included, ensuring full reproducibility of all computational steps reported in this work.

3. Results and Discussion

Upon analyzing the frequency of descriptors for compounds with antidiabetic activity, it was found that most of these compounds contained descriptors such as CHEBI:24431, CHEBI:36963, CHEBI:51143, and CHEBI:35352. Moreover, 40 out of 46 compounds contained CHEBI:33836 (benzenoid aromatic compound), and 27 and 25 compounds, respectively, were classified as organic heterocyclic compounds and organosulfur compounds (CHEBI:24532, CHEBI:33261). It should be noted that the entire input dataset consisted exclusively of approved pharmaceutical agents, each of which is assigned to a specific class within the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system.

Following the principles of phenotypic classification (ATC), the study’s results highlight several key advantages of this approach. Specifically, the PDATC-NCPMKL [

47] model demonstrated its suitability for broad compound screening by enabling the prediction of ATC codes without requiring prior knowledge of a drug’s specific mechanism of action. This is particularly valuable in scenarios where multiple or unknown pathways mediate pharmacological effects. Such capability is consistent with the core concept of phenotypic models, which focus on observable effects rather than target-specific interactions [

47].

Moreover, by predicting ATC code associations, the model facilitates the identification of novel therapeutic applications for existing drugs. This drug repositioning capability operates independently of predefined molecular targets, making it particularly effective for uncovering previously unrecognized drug effects and broadening the therapeutic landscape [

47].

Despite its strong performance, the phenotypic classification approach as implemented in the PDATC-NCPMKL model exhibits inherent limitations. One notable constraint is the lack of target-specific biological interpretability. Since ATC codes represent phenotypic-level drug classifications rather than molecular mechanisms, the associations predicted by the model do not elucidate the specific biochemical targets or pathways involved. Consequently, while the model excels at identifying potential therapeutic applications, it provides limited guidance for rational drug optimization or mechanistic validation. Furthermore, although multiple drug and ATC kernels were integrated to enhance prediction, the model’s reliance on predefined similarity measures and known associations may restrict its applicability to novel or undercharacterized compounds with sparse annotation data.

To further characterize the ontological features associated with antidiabetic activity, the presence frequencies of categorical descriptors derived from the ChEBI and ChemOnt ontologies were compared between active and inactive compounds. Several descriptors exhibited markedly higher prevalence in antidiabetic agents, indicating potential structural or functional relevance.

The strongest differentiators included CHEBI:76983 and its corresponding ChemOnt class CHEMONTID:0000490, both present in 36.96% of active compounds but nearly absent in inactives (0.07%, Δ = 0.369). This was followed by CHEBI:33261 (organosulfur compounds, Δ = 0.367), and several ChemOnt categories such as CHEMONTID:0000270, 0000031, and 0004233, all with presence differences exceeding 0.34. These classes correspond to biologically relevant compound types such as heterocyclic organosulfur derivatives, which may underlie mechanisms of glucose regulation or enzyme modulation.

Among compound-level entities, CHEBI:22712 (organic acid) was found in over 80% of antidiabetic agents compared to 48% of non-antidiabetics (Δ = 0.325), while CHEBI:35358, CHEBI:33552, and CHEBI:35850 also exhibited over threefold enrichment in the active class. Notably, CHEBI:33836 (benzenoid aromatic compound) remained highly prevalent across both classes but still showed a significant difference (84.8% vs. 63.6%, Δ = 0.211), suggesting its relevance in maintaining core aromatic scaffolds commonly found in antidiabetic drugs.

ChemOnt superclasses, including CHEMONTID:0000364 (aromatic heteropolycyclic compounds) and CHEMONTID:0001831 (organonitrogen compounds), also showed moderate discriminative power (Δ > 0.22), further reinforcing the role of nitrogen-containing heterocycles. Similarly, descriptors such as CHEMONTID:0001925, 0003964, and 0000284 indicated notable enrichment among actives, capturing less frequent but structurally distinct motifs.

In general, this analysis highlights that antidiabetic agents share common ontological features related to aromaticity, heteroatom composition, and sulfur/nitrogen functionality, as defined by structured chemical taxonomies. These findings provide additional evidence that ontological classification can complement numerical descriptors in identifying pharmacologically relevant molecular patterns.

Additionally, frequency-based analysis of molecular features calculated using the Mordred descriptor library revealed a set of structural and physicochemical characteristics enriched in antidiabetic compounds. Among the top differentiating descriptors were nS (sulfur atom count in the molecule, frequency: 53.3% vs. 21.3%, Δ = 0.32), GGI10 and JGI10 (topological charge and information indices of order 10, both 86.7% vs. 56.7%, Δ = 0.30), and NssNH/SssNH (frequency: 62.2% vs. 35.8%, Δ = 0.26), reflecting the presence of nitrogen and sulfur atoms in specific hybridization states. The descriptor n6ARing (aromatic 6-membered ring count) also showed notable enrichment (64.4% vs. 38.8%, Δ = 0.26), highlighting the role of aromatic scaffolds in antidiabetic agents.

Several hydrogen bond-related and electronic surface area descriptors were also more prevalent in active compounds, including nHBDon (hydrogen bond donor count, 97.8% vs. 74.0%, Δ = 0.24), SlogP_VSA10 and PEOE_VSA13, indicating differentiated lipophilic and electronic surface profiles. Additionally, C2SP3 (number of secondary sp3-hybridized carbon atoms), NsssCH, SsssCH, and ring descriptors such as nARing and n6aRing further contributed to discriminating the active class.

The descriptor ETA_dEpsilon_D, related to electronic topology and hydrogen bonding potential, was present in all active compounds (100%) versus 77.3% of inactives, further suggesting differences in molecular interaction capacity. Taken together, the most discriminative Mordred features point to a consistent pattern among antidiabetic drugs, characterized by the presence of aromatic rings, heteroatoms (especially sulfur and nitrogen), specific surface properties, and defined topological indices. These findings support the hypothesis that certain substructural and electronic features are characteristic of bioactive antidiabetic molecules and may be useful in predictive modeling.

3.1. Development, Evaluation, and Application of Machine Learning Models Using Categorical Ontological Descriptors

The following algorithms were used for model training: logistic regression, naive Bayes classifiers (Multinomial and Bernoulli models), support vector machine (SVM) for linearly separable classes, k-nearest neighbors (k-NN), random forest, decision tree, linear discriminant analysis (LDA), stochastic gradient descent (SGD) classifier, Lasso regression, Ridge regression, Elastic Net, and gradient boosting.

A detailed analysis of the model training results based on categorical ontological annotations from ClassyFire and ChEBI systems (

Supplementary Materials, Table S2) revealed exceptionally high performance metrics for most models. The best overall performance was achieved by Random Forest with accuracy (0.9979 ± 0.0027) and ROC AUC (1.0000 ± 0.0000), followed by Linear SVM and SGD Classifier with similarly high metrics.

The most stable models (lowest standard deviations) were Random Forest with accuracy 0.9975 ± 0.0027, Gradient Boosting with accuracy 0.9968 ± 0.0035, and Linear SVM with accuracy 0.9989 ± 0.0025. These models demonstrated not only high performance but also high reproducibility of results.

Remarkably, several models achieved perfect Recall (1.0000 ± 0.0000), including Logistic Regression, Linear SVM, k-NN, LDA, Lasso Regression, Ridge Regression, and Elastic Net. This indicates a complete absence of false negatives (FN) for these models on cross-validation data.

Random Forest demonstrated perfect precision (1.0000 ± 0.0000) during cross-validation, meaning a complete absence of false positives. On test data, this model also showed excellent results with precision 1.0000 and F1 Score 0.8000.

The lowest performance among all models was shown by k-NN with accuracy 0.9487 ± 0.0101 and the lowest precision (0.9072 ± 0.0168). Nevertheless, even this model demonstrated high performance compared to results obtained with other types of descriptors.

Analysis of the confusion matrix (

Table 1) on test data confirms the conclusions about high model performance. Gradient Boosting showed the lowest number of false positives (FP = 2), while Random Forest achieved an ideal result with no false positives (FP = 0).

Most models showed minimal false negatives, the score of FN = 2.

When tested on the validation dataset that did not participate in training and data balancing (

Supplementary Materials, Table S3), the results differed substantially, indicating possible overfitting or high model specificity to training data. Ridge Regression showed the best results on validation data with accuracy 0.997, precision 1.000, recall 0.786, and F1 Score 0.88.

Linear SVM and SGD ClassiFier, despite excellent results on test data, showed extremely low performance on the validation set with precision and recall 0.000.

Random Forest maintained high precision (1.000) on validation data but showed low recall (0.214), resulting in an F1 Score of 0.353. Nevertheless, this model demonstrated a good balance between precision and generalization ability.

Multinomial Naive Bayes and BernoulliNB showed the most stable performance between test and validation data, although their overall metrics were lower than those of the top-performing models.

Ridge Regression analysis revealed that the most important features are predominantly ChEBI ontological terms, with CHEBI:35622 showing the highest importance (0.587717). This was followed by CHEMONTID:0000229 (0.556824) and CHEMONTID:0002286 (0.483765). The top-ranking features demonstrate a clear hierarchy of discriminative power, with importance values ranging from 0.587717 to 0.181740 for the most significant descriptors (

Table 2).

Notably, ChEBI terms dominated the top features, accounting for 7 most important descriptors. This suggests that ChEBI’s chemical entity classifications provide particularly strong discriminative power for the classification task. The presence of both CHEBI and CHEMONTID features in the top rankings indicates that both classification systems contribute complementary information for molecular discrimination.

The feature importance distribution shows a gradual decline rather than sharp cutoffs, with several features showing moderate importance (0.2–0.4 range), suggesting that the model relies on a combination of multiple ontological annotations rather than a few dominant features.

Random Forest demonstrated a more distributed feature importance pattern compared to Ridge Regression, with the highest-ranking feature CHEMONTID:0000270 showing an importance of 0.030681 (

Table 3). This more uniform distribution is characteristic of Random Forest algorithms, which tend to distribute importance across multiple features rather than heavily weighting a few dominant ones.

The top features in Random Forest included a more balanced representation of both ChEBI and CHEMONTID annotations, with CHEBI:35358 (0.028784), CHEBI:22712 (0.023023), and CHEMONTID:0004233 (0.021056) among the most important. Interestingly, several features that were highly ranked in Ridge Regression also appeared prominently in Random Forest, including CHEMONTID:0002286, CHEBI:76983, and CHEBI:50492.

The relatively low maximum importance value (0.030681) compared to Ridge Regression reflects Random Forest’s ensemble nature, where importance is distributed across many weak learners, and multiple features contribute to the final decision.

3.2. Development, Evaluation, and Application of Machine Learning Models Using Mordred Descriptors

In this section, the predictive performance of various machine learning classifiers trained on Mordred molecular descriptors is assessed using cross-validation, test, and independent validation datasets (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). Feature importance analyses for Random Forest and Gradient Boosting models are also included (

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9).

Across CV, ensemble methods achieved near-perfect scores: Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Decision Tree attained ≥0.989 accuracy and F1, with Gradient Boosting yielding the highest mcc (0.998 ± 0.004). However, their generalization differed on the test set: Gradient Boosting preserved high accuracy (0.989) but its recall dropped to 0.333, while Random Forest, despite perfect test precision, recalled only 11% of positives, indicating overfitting to the majority class. Classical linear baselines (Logistic Regression, Linear SVM) maintained perfect recall but suffered from severe precision deficits, reflecting the dataset’s imbalance. Regularized linear models (Ridge) and k-NN provided a compromise, achieving balanced-accuracy scores of 0.759 and 0.588, respectively, with moderate mcc values.

Naive Bayes variants delivered consistent CV performance (F1 ≈ 0.90) yet under-performed on the test set, whereas sparsity-oriented models (Lasso, Elastic Net) failed to learn discriminative features (CV F1 = 0). Overall, Gradient Boosting offered the most favorable bias–variance trade-off, combining high test accuracy with the largest test mcc (0.574) among models that did not sacrifice recall completely.

Logistic Regression and Linear SVM predict every positive correctly (TP = 9, FN = 0) but at the cost of 487 false alarms, yielding a specificity of only 6% and precision of 1.8%. Such behavior is common when the decision threshold is left at 0.5 in a severely imbalanced setting.

Random Forest and Gradient Boosting output essentially no false positives (FP = 0) yet miss 88–89% of the true positives, producing perfect or near-perfect precision but poor recall. Their high overall accuracy (>0.98) therefore reflects correct classification of the majority class rather than balanced performance.

Ridge Regression, k-NN, and LDA strike intermediate positions. Ridge, for instance, identifies five of nine positives while limiting FP to 20, giving the highest MCC (0.315) among models that do not collapse recall. LDA reduces FP further (64) while matching Ridge’s TP count (6), leading to the best test balanced-accuracy (0.772).

Lasso and Elastic Net record only one true positive apiece and two false positives, mirroring their near-zero F1 scores in cross-validation and indicating that the applied regularization parameters were overly aggressive for the available signal. Detailed results are presented in

Table 5.

These observations emphasize that, under extreme class imbalance, relying on a single scalar metric (e.g., accuracy) obscures critical type-I/II error trade-offs.

The validation set (

Supplementary Materials, Table S4) contains 14 positives and 738 negatives (prevalence ≈ 1.9%). Logistic Regression achieves the highest recall (92.9%) but triggers 705 false alarms, reducing precision to 1.8% and total accuracy to 6.1%. Linear SVM, Ridge, and SGD predict only the majority class (TP = 0), yielding superficially high accuracy (≥0.981) and ROC-AUC (up to 0.914) while providing zero utility for the minority class (F1 = 0, MCC = 0). Among probabilistic models, Bernoulli NB and k-NN trade limited precision (<7.1%) for moderate recall (64.3%), reaching the best balanced accuracy for non-ensemble methods (0.742).

Tree ensembles dominate overall correlation with ground truth: Gradient Boosting attains the largest Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC = 0.651) by combining perfect precision, zero false positives, and a recall of 42.9%, while Random Forest delivers a similar balanced-accuracy (0.714) at the expense of one false positive (precision = 85.7%). Decision Tree achieves a more even trade-off (precision = 44.4%, recall = 28.6%), but its MCC (0.347) trails the boosted ensemble.

The top molecular descriptors driving model decisions for Random Forest (

Table 6) and Gradient Boosting (

Table 7) were distinct:

Table 6 lists the seven most influential descriptors in the Random-Forest (RF) model. The RF importance profile is comparatively flat: the leading atom-type electrotopological descriptor ATS4s accounts for only 1.8% of the total split-gain, followed closely by ring-substitution feature MAXsssCH (1.4%) and the charge-weighted surface area WNSA2 (1.3%). Three additional surface/shape indices—VSA_EState5, SpMAD_Dzare, and SpMAD_Dzpe—each contribute ≈ 1.2%, suggesting that the forest leverages a broad set of weak signals rather than a few dominant cues.

Table 7 shows the corresponding ranking for the Gradient-Boosting (GB) model. In contrast to RF, GB is heavily driven by a single descriptor: the electron-state partitioned van der Waals surface EState_VSA10 explains 26.9% of the model’s cumulative gain. The next descriptor, VSA_EState5, contributes 15.5%, after which importance values drop sharply (<5%). Notably, two descriptors—VSA_EState5 and ATS4s—appear in the top list of both ensembles, indicating consistent predictive value across learning paradigms. The steep importance decay in GB implies that model interpretability can be focused on a compact subset of surface-charge and autocorrelation features without substantial loss of explanatory power.

3.3. Generation of New Molecules Based on SMILES Representation

Molecular structures were represented using the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES), a linear string format that encodes molecular graphs as character sequences. This representation enables the formulation of molecular generation as a character-level language modeling task, where the objective is to predict the next character in a SMILES sequence given the preceding context.

A dataset of 46 antidiabetic SMILES sequences (

Supplementary Materials, Table S1) was used. To generate syntactically distinct yet structurally equivalent representations, a stochastic non-canonical SMILES generation algorithm was applied. Each original SMILES string was first converted into a molecular graph using the Chem.MolFromSmiles() function from the RDKit library. Subsequently, multiple non-canonical SMILES strings were generated via the MolToSmiles() function with parameters canonical = False and doRandom = True, disabling canonicalization and enabling random graph traversal.

This procedure was repeated for 10,000 iterations per molecule. Duplicate sequences were removed using a set data structure, resulting in a dataset of 227,924 unique non-canonical SMILES sequences. This dataset is suitable for training machine learning models, augmenting chemical databases, and analyzing molecular representation equivalence.

Following standard procedures [

48], a vocabulary of all unique characters in the dataset was constructed. Character-to-index and index-to-character mappings were defined, and SMILES strings were converted into integer sequences and subsequently one-hot encoded. A batching function divided the data into fixed-length mini-batches, with target sequences offset by one character for next-character prediction training.

A multi-layer Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network was adopted, consistent with the reference implementation [

48]. The architecture included dropout for regularization and a fully connected output layer to project hidden states to the character space. This configuration is well-suited for modeling long-range dependencies in SMILES syntax, such as ring closures.

Training was conducted using the Adam optimizer with a cross-entropy loss function. The training process followed the original protocol, including hidden state initialization, one-hot input encoding, and periodic validation to monitor convergence. GPU acceleration was utilized when available.

Molecule generation was performed using an autoregressive sampling approach. Beginning with a user-defined prime string, the model iteratively predicted and appended characters. Top-k sampling was used to balance structural diversity and chemical plausibility in the generated sequences.

The validity of the generated SMILES was confirmed using cheminformatics tools, ensuring both syntactic and chemical correctness. Consistent with the findings of the original study, the model produced structurally valid molecules that reflected the chemical characteristics of the training dataset.

Molecular structure generation was implemented using the approach described in the reference article “Generating Molecules Using a Char-RNN in PyTorch” [

48], which details a recurrent neural network (Char-RNN) method for SMILES-based molecule generation.

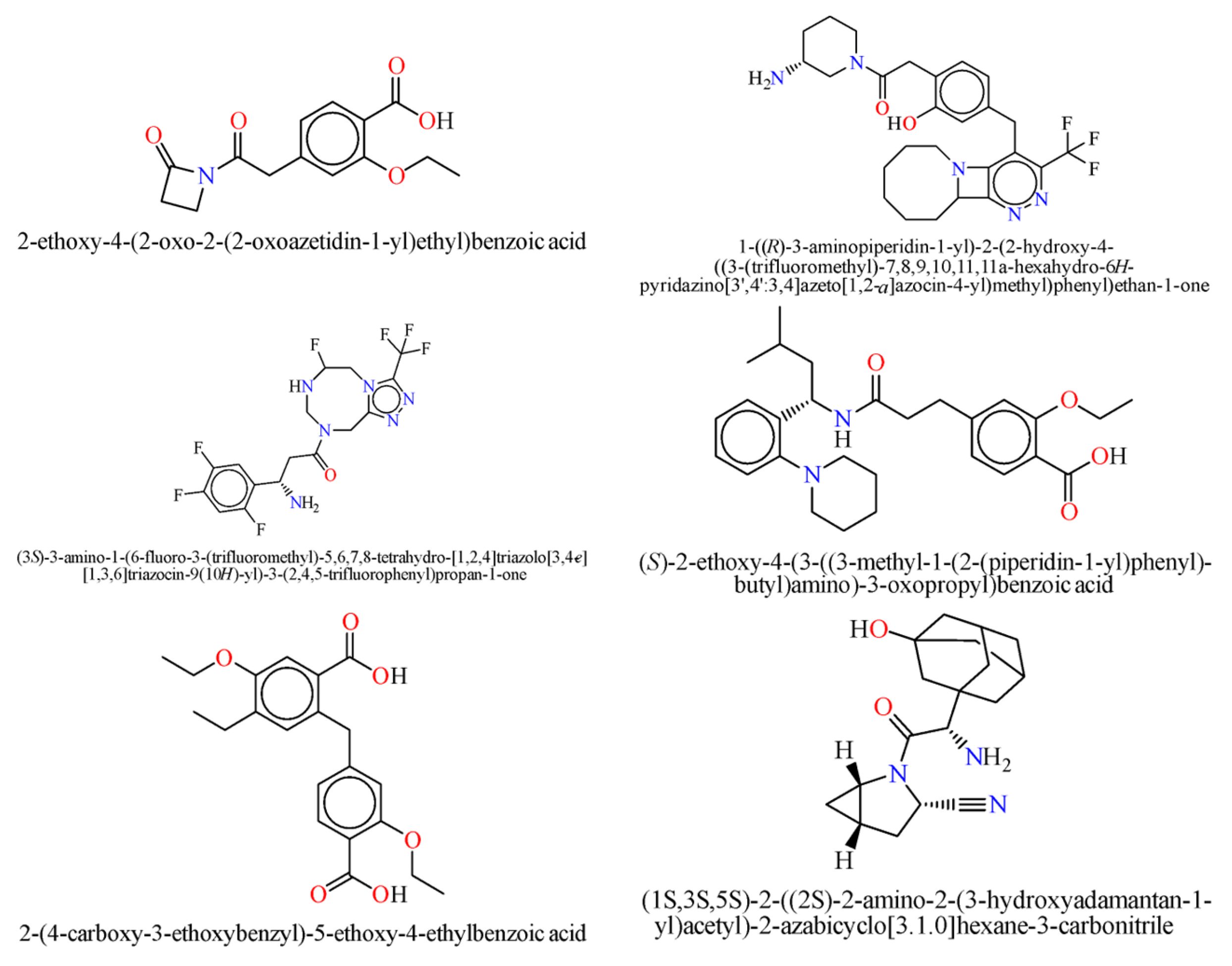

The neural network was trained on a dataset of 46 molecules, resulting in the generation of 1179 new SMILES sequences (

Figure 1).

3.4. Selection of Generated Molecules Using the Developed Prediction Models

After generating the SMILES sequences, a dataset was prepared for predicting the likelihood of antidiabetic activity in the generated molecules, following the same procedure used to generate descriptors with mordred and ClassyFire.

Thus, the data on the predicted probabilities of antidiabetic activity for various compounds were analyzed using different machine-learning models. To select the top 10 most promising compounds, the selection criteria included high average predicted probabilities of antidiabetic activity across all models, consistency of high scores across different models, and preference was given to compounds with the highest scores in the largest number of models (

Table 8).

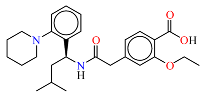

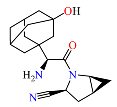

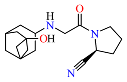

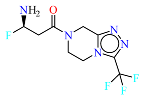

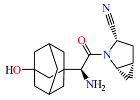

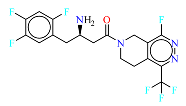

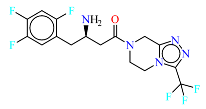

As a result, the most promising compounds in terms of predicted antidiabetic activity were

Slightly lower predicted probabilities of antidiabetic activity were observed for the following SMILES sequences (see

Table 6):

No. 447—Gradient Boosting (0.99998), Random Forest (0.92), Decision Tree (1.0), LDA (0.999743)

No. 628—Gradient Boosting (0.99998), Random Forest (0.92), Decision Tree (1.0), LDA (0.999743)

No. 1163—Gradient Boosting (0.99998), Random Forest (0.92), Decision Tree (1.0), LDA (0.999743)

No. 52—Gradient Boosting (0.872455), Random Forest (0.81), Linear SVM (0.553283), Logistic Regression (0.93189)

No. 108—Gradient Boosting (1.0), Random Forest (0.65), Logistic Regression (0.65996)

No. 20—Gradient Boosting (0.99998), Random Forest (0.92), Decision Tree (1.0), LDA (0.999742)

No. 451—Gradient Boosting (0.872455), Random Forest (0.81), Linear SVM (0.553283), Logistic Regression (0.93189)

No. 843—Gradient Boosting (0.872455), Random Forest (0.81), Linear SVM (0.553283), Logistic Regression (0.93189)

As for the novelty of the obtained structures, these sequences are likely to already be known. Therefore, in the next stage of generated structure selection, the shortlisted molecules were checked against the Reaxys and Manifold databases.

Further analysis of the presence of generated molecules was carried out using the AI-Driven Chemistry ChemAIRS

® platform

https://www.chemical.ai/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

During the study, it was found that Molecule No. 20 is not registered in either the Reaxys or ChemAIRS® platform.

According to the conducted analysis, Molecules 52, 108, 447, 451, and 843 were identified in the ChemAIRS® platform and are available for order from different commercial companies.

Molecule No. 540 was also not registered in either the ChemAIRS® platform or Reaxys.

Likewise, Molecule No. 967 was not found in the ChemAIRS® platform.

There are several potential mechanisms of action for the generated compounds; for instance, molecule No. 967 shares motifs with DPP-4 inhibitors. This observation offers a rational hypothesis for future molecular docking and bioassay testing.

3.5. Biochemical and Pharmacophoric Patterns Revealed by Feature Importance Analysis

An in-depth analysis of the top-ranking features identified by Ridge Regression and Random Forest models reveals several key biochemical and pharmacophoric patterns that may underlie the antidiabetic activity of compounds in the dataset.

Lipophilic Fragments and Fatty Acid Derivatives. The highest-ranked feature in the Ridge Regression model, CHEMONTID:0001729 (fatty acids and derivatives), underscores the significance of lipophilic moieties in mediating antidiabetic activity. This observation aligns with the established structure–activity relationships of PPAR agonists, such as thiazolidinediones and fibrates, which incorporate long-chain hydrophobic elements that facilitate receptor binding and metabolic regulation.

As demonstrated in this study [

49], the five-drug class model utilizes phenotypic predictors derived from nine routinely collected clinical features to estimate the relative glycemic effectiveness of commonly used glucose-lowering therapies. While this approach enables broad applicability and implementation across real-world settings, it does not explicitly incorporate mechanistic or target-specific information (e.g., drug-target interaction with SGLT2 or PPARγ pathways). The observed differential long-term outcomes—including risks of glycemic failure, renal progression, and cardiovascular events—suggest underlying heterogeneity in drug response that may benefit from further mechanistic stratification. Therefore, future integration of target-specific modeling frameworks, alongside this phenotypic model, may enhance predictive precision by aligning physiological drug actions with patient-level molecular or biomarker profiles, ultimately supporting more personalized and biologically informed treatment decisions [

49].

Aromatic Heterocycles and Lactams. Several highly ranked ontological classes, including CHEMONTID:0000229 (heteroaromatic compounds), CHEMONTID:0001894 (aromatic heteropolycyclic compounds), and CHEMONTID:0001819 (lactams), indicate the prevalence of these structural motifs in known antidiabetic agents. Aromatic heterocycles frequently serve as scaffolds in kinase inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors, and sulfonylureas, while lactam rings are often included to enhance metabolic stability and receptor binding affinity.

Convergent Features in Ridge and Forest Models. The joint identification of CHEMONTID:0000490 (organic oxygen compounds) and CHEBI:76983 (L-pipecolate) among the top features in both Ridge Regression and Random Forest models suggests the robustness of these descriptors. These compounds may contribute to modulating oxidative stress and mitochondrial function, processes critically involved in diabetes pathogenesis.

Amino Acid Derivatives and Bioactive Peptides. The inclusion of features such as CHEBI:48277 (Cysteinylglycine) emphasizes the relevance of peptide-like or amino acid–derived moieties. These fragments may mimic endogenous signaling peptides or influence redox modulation and insulin sensitization mechanisms.

Neuroactive Structures and Alkaloid Derivatives. The presence of CHEMONTID:0004343 (alkaloids and derivatives) implies that certain antidiabetic candidates may also exert neuromodulatory effects or interact with neurotransmitter systems. This may be pertinent to diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction and the emerging involvement of the gut–brain axis in metabolic control.

Collectively, these findings highlight the multidimensional pharmacophoric landscape of antidiabetic compounds and underscore the predictive value of integrating chemical ontology (ChemOnt) and compound-specific identifiers (ChEBI) in machine learning–driven drug discovery.

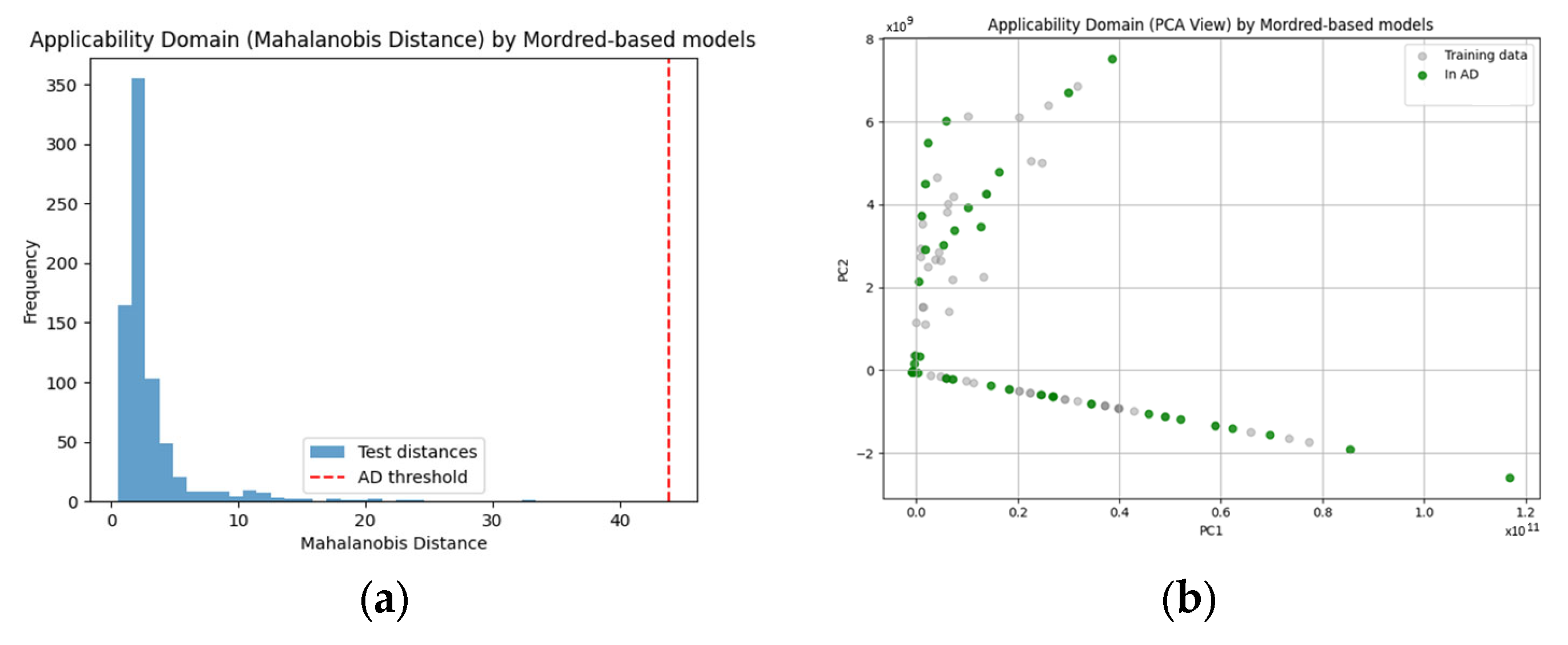

3.6. Applicability Domain and Prediction Reliability

To improve the interpretability and reliability of the developed models, we assessed their applicability domain (AD)—the chemical space within which the model is expected to produce reliable predictions. AD was determined using the Mahalanobis distance method, which quantifies how far a new sample lies from the centroid of the training data in descriptor space.

For each descriptor set, we calculated the Mahalanobis distance between validation/test samples and the centroid of the training set. A cutoff threshold was derived based on the 95th percentile of the Mahalanobis distances within the training set, using the chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of descriptors.

Applicability Domain (Mahalanobis Distance) by Mordred-based models:

Threshold: 43.8922

Number of validation samples within AD: 752 out of 752

Applicability Domain (Mahalanobis Distance) by ClassyFire-based models:

Threshold: 49.8229

Number of validation samples within AD: 185 out of 879

These results indicate that Mordred-based models (

Figure 2) exhibit excellent descriptor coverage across the chemical space of the validation set, as all external compounds fall within the AD. In contrast, ClassyFire-based models (

Figure 3) have a much narrower applicability domain, with only 21.1% of validation compounds falling within the reliable prediction space. This observation is consistent with the higher structural diversity and sparsity of categorical ontological annotations used in the ClassyFire and ChEBI systems.

To aid interpretability, we also visualized the AD boundaries using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Compounds falling outside the AD were clearly separated from the training distribution in reduced two-dimensional space, further reinforcing the importance of AD evaluation prior to applying the model to novel chemical entities.

In summary, integrating AD analysis allows identification of regions where model predictions are reliable and highlights scenarios in which predictions should be treated with caution or further validated. This is especially critical when deploying models in real-world applications such as virtual screening or drug repurposing (

Table 9).

The AD filter retained 190 structures (2 actives, 188 inactives). When restricted to this chemically homogeneous sub-space, nine of the thirteen classifiers—Logistic Regression, Random Forest, LDA, Lasso, Elastic Net, Decision Tree, Gradient Boosting, and the baseline k-NN (with two residual false positives)—achieved perfect or near-perfect recognition of both classes (ACC, F1, MCC, balanced-accuracy = 1.0). This behavior indicates that, within the multivariate region defined by the Mahalanobis metric, the actives are well separated from the bulk of the inactives and are linearly separable.

By contrast, Naive-Bayes variants suffered pronounced overprediction: BernoulliNB and Multinomial NB produced 19 and 33 false positives, respectively, lowering precision to <10% and MCC to ≤0.293, even though recall remained 1.0. Their assumption of descriptor independence appears ill-suited to the tightened feature covariance structure imposed by the AD.

Finally, margin-based linear methods (Linear SVM, SGD, Ridge) collapsed to the majority class, failing to identify either active (recall = 0, MCC = 0, balanced-accuracy = 0.5). This outcome suggests that their decision boundaries, optimized on the full training distribution, shrink inside the AD to exclude the minority region altogether.

Overall,

Table 9 demonstrates that AD pruning can dramatically amplify model discrimination—turning several previously moderate performers into perfect classifiers—while simultaneously exposing methods that rely on unrealistic distributional assumptions or overly rigid margins. In the present setting, ensemble and regularized logistic models provide the most reliable in-domain predictions, whereas independence-based and hard-margin techniques require additional calibration or hybrid AD strategies to remain competitive.

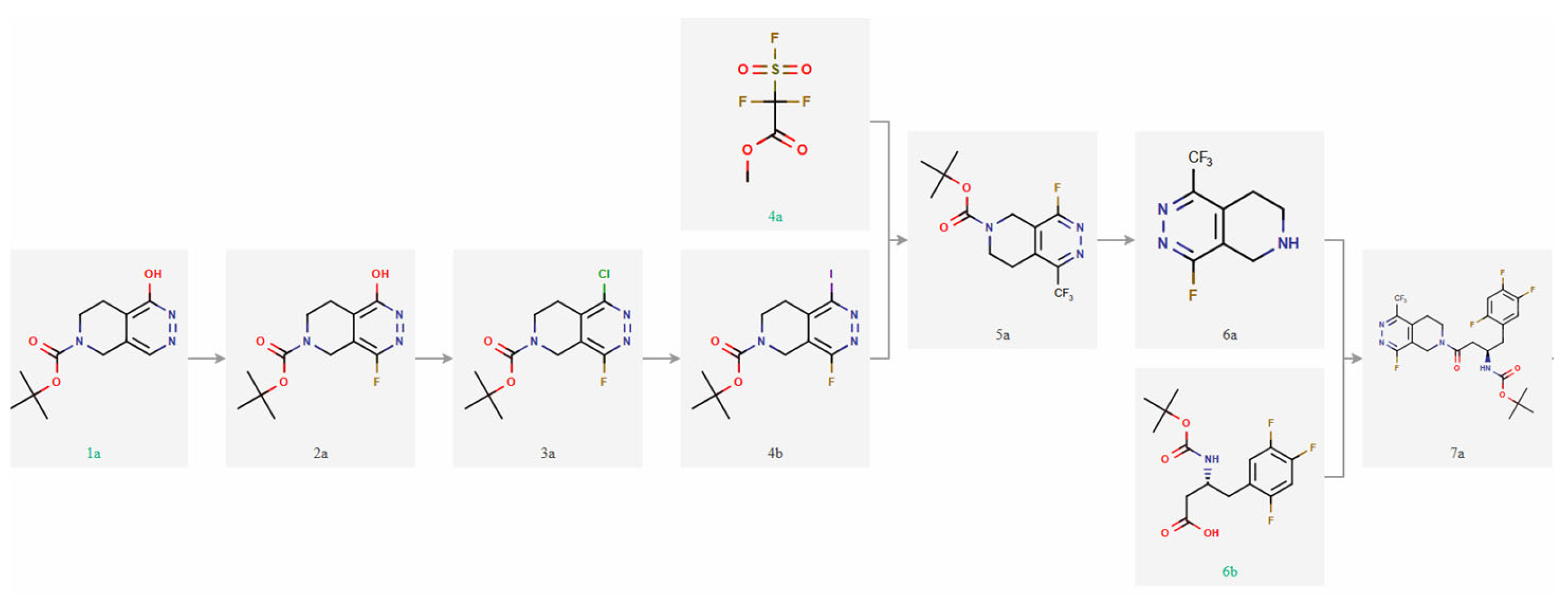

3.7. Retrosynthesis and Molecule Synthesis Using AI

The retrosynthesis (

Figure 4), performed using the ChemAIRS

® platform

https://www.chemical.ai/retrosynthesis (accessed on 6 June 2025), incorporates classical and modern organic transformations, including amide bond formation, heterocyclization, electrophilic aromatic substitution, and late-stage functionalization. The synthetic route comprises several key stages, labeled as [Step 1A] through [Step 7A]. The entire synthetic plan, carried out with the assistance of ChemAIRS

®, is characterized by atom- and step-economy, avoids unnecessary protection-deprotection steps, and provides a practical framework for constructing drug-like heterocyclic scaffolds. Its design reflects both synthetic feasibility and medicinal relevance, supporting future applications in drug discovery and chemical biology.

3.8. Limitations and Applicability to Drug Discovery

A performance drop between cross-validation and independent validation metrics was analyzed, focusing on balanced accuracy and Matthew’s correlation coefficient (MCC). The analysis revealed the following key observations:

Simple models, such as Logistic Regression, Linear SVM, and SGD Classifier, showed minimal changes in performance, with balanced accuracy differences within ±4% and moderate MCC reductions. This suggests that these models generalize well to unseen data.

In contrast, complex models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Ridge Regression) exhibited larger drops, with declines exceeding 30% in balanced accuracy and up to 95% in MCC. However, these differences are more plausibly attributed to distributional shifts and test set instability rather than classical overfitting.

Specifically, the training data was balanced using SMOTE (50:50), while the test set remained highly imbalanced, with only 9 positive samples among 527 total (~1.7%). Such a class distribution mismatch introduces considerable metric variability, particularly in MCC, which is highly sensitive to small changes in rare class predictions.

No signs of data leakage were detected, and data splits were performed appropriately.

These findings indicate that the observed performance changes are more consistent with experimental design constraints and class distribution effects than with model overtraining.

A major limitation of the present study lies in the composition of the dataset. The models were trained and evaluated exclusively on compounds with established pharmacological use as antidiabetic agents, specifically classified under ATC class A10 (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification). The availability of such compounds is limited, and new antidiabetic drugs are introduced very infrequently. As a result, the dataset cannot be readily expanded, and the experimental design cannot be restructured without access to newly approved or discovered agents.

Despite these constraints, the developed models retain value as in silico tools for early-stage drug discovery, particularly in the following contexts:

Prioritization of large virtual libraries to identify candidates with predicted antidiabetic activity;

Hypothesis generation and compound ranking in cheminformatics pipelines;

Selection of compounds for further in vitro or in vivo validation.

The use of these models should be restricted to compounds that fall within the applicability domain (AD) defined by the training data. Applicability can be assessed using techniques such as Mahalanobis distance or PCA-based visualization. Predictions for compounds outside this domain should be interpreted with caution.

Given the limited number of positive samples, the high-class imbalance, and the constraints of real-world drug availability, these models should not be used as standalone decision-making tools. Instead, they are best employed as pre-screening instruments that complement experimental and domain-based evaluation strategies.