1. Introduction

Oral health represents an integral component of systemic physiology, reflecting the interplay between the oral microbiome, host immune regulation, and metabolic homeostasis. The oral cavity functions as the initial segment of both the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts and serves as a complex microbial habitat hosting an estimated 700 bacterial species and up to one trillion microorganisms [

1,

2]. These commensal communities help maintain ecological balance, whereas dysbiosis involving pathogenic species such as

Porphyromonas gingivalis disrupts immune equilibrium and drives chronic inflammation.

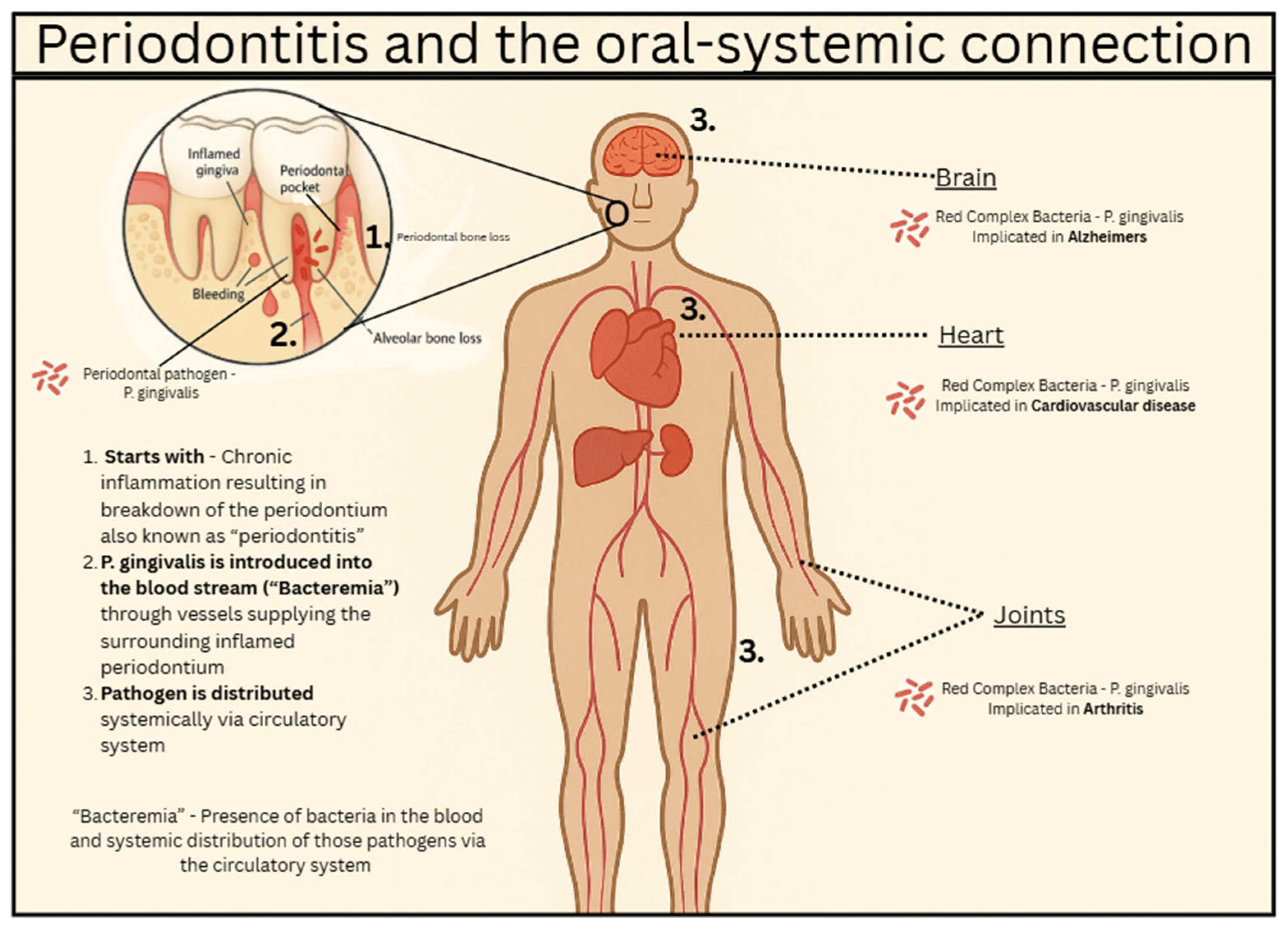

Gingivitis is a plaque-induced, reversible inflammation confined to the gingiva, presenting with erythema, edema, and bleeding on probing but without attachment or bone loss. When inflammation becomes persistent, gingivitis may progress to periodontitis, a chronic destructive process marked by alveolar bone resorption and loss of periodontal attachment. The transition depends on several risk modifiers, including smoking, diabetes, and genetic susceptibility [

3]. During this progression,

P. gingivalis and other pathogenic taxa trigger the release of cytokines such as interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-6, amplifying tissue destruction and promoting bacterial translocation into the bloodstream (bacteremia) [

4].

Recent research (2023–2025) provides compelling mechanistic evidence linking periodontitis and systemic diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and atherosclerosis.

P. gingivalis and

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans have been identified in atherosclerotic plaques and AD brains, where they initiate endothelial dysfunction, microglial activation, and blood–brain-barrier (BBB) disruption [

5,

6]. Kong et al. (2025) demonstrated that periodontitis-induced neuroinflammation activates the IFITM3–Aβ axis, producing AD-like pathology in vivo [

7]. Large-scale epidemiological analyses further show that poor oral health more than doubles AD risk, while systematic reviews from 2024–2025 support causal associations mediated by microbial dissemination and systemic inflammation [

8,

9].

These findings underscore that maintaining oral health is a modifiable determinant of chronic disease prevention rather than an isolated dental concern. However, translation of this knowledge into routine preventive practice remains limited. The present narrative review therefore synthesizes recent mechanistic evidence connecting oral and systemic diseases; summarizes evidence-based preventive and therapeutic strategies for maintaining oral health; and highlights emerging technologies such as salivary diagnostics, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence that support personalized, preventive oral-systemic care.

2. Biological Mechanisms Linking Oral and Systemic Health

Several studies have shown that in patients with severe periodontitis, they have elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators and neutrophils in the blood. Interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and fibrinogen are some inflammatory markers seen in these patients. The function of these molecules is to increase inflammation in tissues, which is good for fighting infections, but when they are in the blood, you can have systemic effects. Low grade systemic inflammation has been shown to be associated with the development of comorbidities in patients with periodontitis leading to the development of other diseases. Sustained inflammation over a prolonged period of time can lead to the damage of tissues or organs, including an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease [

2].

Systemic inflammation associated with periodontitis is thought to be caused by the bacteria in the oral cavity translocating into the bloodstream. Periodontitis is marked by the inflammation and ulceration of the periodontal tissue surrounding the tooth structures. These ulcerations are thought to allow a passageway for these periodontal bacteria to enter into the bloodstream causing bacteremia.

P. gingivalis is one of the most common periodontal bacteria and is known as one of the most detrimental to your health. One study showed that

P. gingivalis was identified in the brains of patients who died of AD leading researchers to discover the correlation between periodontal health and the risk of developing AD. In addition to this correlation, mice that were infected with oral

P. gingivalis resulted in the bacterial colonization of the brain tissue. Elevated levels of Aβ1-42 were also seen, which is a component of amyloid plaque (beta-amyloid cluster accumulation). Amyloid plaque is a hallmark of AD [

2,

10].

Endothelial dysfunction can also result from the translocation of the oral microbiome. When the bacteria enter the blood causing inflammation, endothelial cells will dilate and become more permeable to inflammatory mediators and lymphocytes through a process known as diapedesis. Lymphocytes will proliferate and release cytokines which, along with inflammatory mediators, will promote further inflammation. Key inflammatory mediators are histamine and bradykinin. Cytokines that are released bring in more lymphocytes and the cycle of inflammation continues, damaging the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels.

Oral pathogens contribute to brain pathology via both neuroinflammation (microglial activation) and vascular injury; these processes overlap substantially in Alzheimer’s disease and atherosclerosis.

Microglial activation and blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption: Periodontal bacteria such as

P. gingivalis release virulence factors (e.g., lipopolysaccharide, gingipains) that can enter the circulation, degrade tight junction proteins (occludin, claudin-5), and weaken BBB integrity. This permits bacterial products or exosomes to reach brain parenchyma where they activate microglia, promote proinflammatory cytokine release (IL-1β, IL-6), and contribute to amyloid-β accumulation and tau pathology. For example, a recent study showed that periodontitis increases BBB permeability, accelerating AD [

11].

Oral pathogens also accelerate vascular injury, a critical bridge between systemic inflammation and neurodegeneration. Bacteria from the oral pathogens are found within atherosclerotic plaques, where they promote endothelial dysfunction, macrophage activation, and foam cell formation, resulting in chronic vascular inflammation and plaque instability [

5]. These processes not only drive cardiovascular disease but also impair cerebral perfusion and promote BBB leakage, conditions strongly associated with AD progression

Figure 1. Thus, pathogen-induced vascular inflammation amplifies both systemic atherosclerotic risk and neurovascular compromise, creating a dual pathway by which oral infections contribute simultaneously to vascular disease and Alzheimer’s pathology [

5].

3. Evidence-Based Oral Health Interventions and Strategies

3.1. Periodontal Therapy

Scaling and root planing (SRP), often combined with supportive periodontal maintenance, is the gold standard for managing periodontitis. Its primary aim is to mechanically disrupt subgingival biofilm, reduce periodontal pocket depth, and allow for tissue healing. Beyond local benefits, SRP exerts measurable effects on systemic inflammation. Clinical studies consistently report reductions in serum CRP, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) following therapy, reflecting decreased systemic inflammatory burden [

3]. Such improvements are clinically significant because these biomarkers are central mediators in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and neurodegeneration [

2,

10].

Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that SRP improves endothelial function, with measurable increases in flow-mediated dilation within weeks [

2]. This suggests that periodontal therapy not only reduces oral inflammation but also improves vascular health. Meta-analyses have confirmed modest yet significant reductions in glycated hemoglobin in patients with diabetes following SRP, underscoring its systemic metabolic impact [

10]. Maintenance therapy is crucial. Without consistent follow-up, inflammatory markers and clinical attachment loss tend to rebound, negating the systemic benefits [

7].

SRP is a modifiable upstream intervention that may lower risk for AD and cardiovascular disease. It reduces systemic inflammation and limits bacterial translocation into circulation [

2,

10]. Evidence across inflammatory, metabolic, and vascular markers supports its role in preventive medicine frameworks.

Actionable step: Periodontal therapy, combined with regular maintenance visits, should be prioritized not only for preserving dentition but also for reducing systemic inflammatory load and downstream risk of chronic diseases.

3.2. Interdental Cleaning

Interdental cleaning is known to be a necessary adjunct to simply just brushing your teeth. Oftentimes tooth brushes are unable to reach the interproximal contacts between teeth leaving plaque accumulation. This plaque can lead to caries, gingivitis, or even periodontitis. Flossing is often considered the best way to remove interdental plaque, but it can cause bleeding of the gingiva. Water flossers are also believed to be effective; however, they are believed to remove more of the soft or unattached plaque. Oral irrigation leads to less bleeding of the gingiva. A meta-analysis evaluated the effect of interproximal cleaning methods on the progression of gingivitis including flossing, oral irrigation, and interdental brushes. Flossing had little to no effect in reducing gingivitis. Oral irrigation showed a significant impact on the reduction of gingival bleeding and inflammation. Reducing the amount of gingival and periodontal ulcerations will reduce the likelihood of introducing bacteria into the blood stream causing bacteremia [

11].

Actionable Step: Use interdental cleaning methods as an adjunct to tooth brushing to remove interproximal plaque accumulation. If you have no gingivitis, you could use traditional floss, interdental brushes, or water flossers. If you have gingivitis or periodontitis, use oral irrigation to gain the benefit of interproximal cleaning while also reducing bleeding/gingivitis in the surrounding tissue [

11].

3.3. Nutrition and Timing

Bacteria break down fermentable sugars and produce acid as a byproduct, dropping the pH below the critical pH of 5.5 and initiating demineralization of enamel. Sucrose is the most cariogenic sugar. The amount of sugar that is consumed in the diet has a proportional effect on the amount of demineralization. Surprisingly, studies have also shown that the frequency of consumption of sugars might be more detrimental than the amount of sugar consumed. When you eat acidic foods, the pH drops below 5.5. After eating, it takes around 20–60 min for the pH to return to normal. The more frequently food is consumed, the longer the oral cavity stays below the critical pH and the enamel is vulnerable [

12].

Soft drinks have a low pH ranging from 2.5 to 3.5, dropping the pH of the oral cavity below 5.5, initiating the demineralization of enamel.

Using some sugar substitutes have been shown to decrease the incidence of caries. Xylitol has been shown to decrease the amount of plaque formation, in turn decreasing the number of bacteria in close proximity to enamel [

13].

Eating sticky foods such as chewy candies has also been shown to stick to teeth and trap bacteria and sugars in close proximity to the structure of the tooth leading to the increase in the amount of caries development.

Starch, which is found in foods such as bread, pasta, etc., is widely accepted to have a low cariogenicity.

Studies have shown that consuming less than 15 to 20 kg/year of fermentable sugars leads to low incidence of dental caries.

Actionable step: Eat a diet low in easily fermentable sugars, especially sucrose. Avoid acidic foods such as soft drinks, coffee, lemon juice, etc., that lower the pH of the mouth. Chew gum such as Xylitol gum or sugar-free gum. Avoid eating frequent meals or snacking in between meals.

3.4. Composite Restorations

While dental amalgam fillings have long been considered durable and generally safe for most individuals, their mercury content raises concerns; especially for vulnerable groups such as children, pregnant or nursing women, and those with known sensitivities [

14]. When amalgam fillings are placed in or removed from teeth, they can release a small amount of mercury vapor. Amalgam can also release small amounts of mercury vapor during chewing. People can absorb these vapors by inhaling or ingesting them [

15]. Elevated systemic mercury is convincingly linked, by recent human data, to neurotoxicity, developmental harm in utero/childhood, immune-mediated and proteinuric kidney disease, and cardiovascular dysfunction, with risk magnitude rising with dose and form of mercury [

16]. The extent to which mercury leached out by amalgam fillings contributes to systemic illness has been debated for years. Considering that humans are exposed to other sources of mercury such as seafood, it is logical to avoid the mercury of amalgams if there is a preferred alternative. Composite resin fillings are mercury-free, aesthetic, and bond conservatively to tooth structure making them a preferred alternative for patients wary of mercury exposure or seeking more biocompatible options [

17].

When removal of amalgam is indicated, whether for patient preference or medical caution, it is critical to follow rigorous safety protocols. The SMART protocol (Safe Mercury Amalgam Removal Technique), developed by the International Academy of Oral Medicine and Toxicology, incorporates multiple protective measures: high-volume suction, air filtration systems, rubber dam isolation, pre-procedure mouth rinses (e.g., with activated charcoal), patient barrier protection, and proper amalgam waste capture to minimize mercury vapor exposure to patients, clinicians, and the environment. These best practices not only reduce inhalation risks but also prevent the release of mercury into clinic air and public water systems, aligning with evolving environmental health standards [

18].

Actionable step: Opt for composite resin for fillings and make sure your dentist uses the SMART protocol if an amalgam filling is being removed.

3.5. Maximize Salivary Flow

Saliva plays an integral role in the health and function of the oral cavity, acting as a buffer, carrying minerals for remineralization, containing antibodies, antimicrobial peptides etc. When enamel is demineralized, Calcium and Phosphorus that is found in the saliva are what is used to rebuild the hydroxyapatite structure. Acting as a buffer when an acid lowers the pH of the mouth, saliva utilizes the carbonic acid/bicarbonate buffer to raise the pH to normal levels at around a pH of 7. A 2011 study showed that xerostomia, or dry mouth, results in an increased risk of caries due to the decrease in function of saliva [

15]. Some medicines such as anticholinergic medications reduce salivary flow as a side effect. Reduced salivary flow decreases the buffering capacity and mineral content of saliva. Xerostomia leaves patients with a significant increase in the susceptibility to dental caries along with other oral health complications [

19].

Chewing gum is one way that some patients with xerostomia can increase salivary flow. Xylitol gum has historically been shown to be the most effective at reducing caries due to the inability of bacteria to ferment xylitol, while also increasing the saliva production.

Actionable step: Stay hydrated by drinking ample amounts of water. Avoid certain drugs that reduce salivary flow unless absolutely necessary, or if instructed by a healthcare provider. Chew sugar-free gum or Xylitol gum to increase saliva production.

3.6. Timing of Brushing

Tooth brushing is widely acknowledged as a preventive cornerstone against dental caries and erosive tooth wear (ETW), yet the optimal timing remains debated. A 2024 scoping review by Fernández et al., published in

Caries Research, examined 17 human-relevant studies where 16 addressing ETW and one on dental caries using in vivo, in situ, or in vitro models with human saliva and fluoride exposure. The review found that using fluoride toothpaste immediately after an erosive challenge does not increase the risk of ETW, regardless of brushing timing [

20]. While some studies explored delaying brushing up to one hour or tailoring recommendations to specific risk profiles, these were less common and lacked robust support. Overall, brushing immediately after meals particularly with fluoridated toothpaste is considered safe and effective in both caries prevention and minimizing erosive wear [

20].

Outside of this scoping review, the ADA recommends brushing twice daily with a soft-bristled toothbrush, especially before bed and in the morning upon waking to disrupt bacterial biofilm, counteract saliva reduction during sleep, and reinforce enamel with fluoride. Dental associations recommend delaying brushing for 30–60 min after consuming acidic foods or beverages (like citrus or coffee), to allow enamel remineralization and reduce risk of abrasion [

21].

Actionable step: Brush teeth twice daily with a soft-bristled toothbrush, once upon waking and again before bedtime. Gentle, circular strokes with light pressure are recommended to effectively remove biofilm while minimizing abrasion. Following exposure to intrinsic acids (e.g., reflux or vomiting) or extrinsic acids from foods (such as citrus fruits, berries, tomatoes, and vinegar-based products) and beverages (including soft drinks, wine, and fruit juices), it is advisable to delay brushing for 30–60 min.

3.7. Limiting Antiseptic Mouthwash

Several clinical studies have demonstrated that the routine use of antiseptic mouthwashes can lead to an increase in blood pressure by disrupting the oral microbiome on the dorsum of the tongue. The tongue harbors nitrate-reducing bacteria such as

Neisseria,

Rothia, and

Actinomyces, which convert dietary nitrate into nitrite, the substrate for systemic nitric oxide (NO) production, a critical vasodilator for vascular health. When these bacteria are suppressed, the enterosalivary nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway is impaired, resulting in reduced NO bioavailability and higher blood pressure [

22,

23]. Bondonno et al. showed that chlorhexidine mouthwash uses significantly increased systolic blood pressure within one week by reducing oral nitrite production [

22].

Further mechanistic evidence comes from Tribble et al., who found that antiseptic mouth rinses alter the tongue microbiome composition, reducing nitrate-reducing species and disrupting nitric oxide homeostasis. Their study highlighted that twice-daily chlorhexidine rinsing not only shifted the bacterial population but also caused measurable increases in blood pressure [

23]. Similarly, Woessner et al. reported that nitrate supplementation to lower blood pressure was blunted when participants used antibacterial mouthwash, reinforcing the causal role of oral microbes in systemic vascular regulation [

24].

Given this evidence, the routine use of antiseptic mouthwash should be reconsidered. While short-term use may be necessary for specific dental indications such as controlling acute gingivitis, reducing bacterial load after surgery, or managing periodontal infections, its indiscriminate use may have unintended cardiovascular consequences. Unless a dentist specifically prescribes it for a targeted condition, antiseptic rinses should not be a standard component of daily oral hygiene. Instead, mechanical cleaning (toothbrushing, flossing, tongue scraping) and fluoride toothpaste are sufficient for most individuals, preserving the beneficial nitrate-reducing bacteria that contribute not only to oral health but also to blood pressure regulation.

Actionable Step: Do not use antiseptic mouthwash as part of daily oral hygiene unless prescribed by your dentist.

3.8. Probiotic and Postbiotic Lozenge

Optimizing the oral ecosystem promotes periodontal health.

Streptococcus salivarius is a beneficial bacterium that can provide a robust defense against

Streptococcus mutans [

25]. In a randomized controlled trial, 61 participants with gingivitis aged between 18 to 25 years old were randomized to receive a daily

S. salivarius M18 (500 million CFU) lozenge or a placebo nightly after brushing, for four weeks. The probiotic group showed 31% reduced gingival inflammation index [

26]. In another trial, a three-month supplementation with

S. salivarius M18 strain reduced gingival bleeding and dental plaque in young adults with gingivitis [

27]. These findings are important because untreated gingivitis can advance to periodontitis [

3].

Other studies have looked at postbiotics’ impact on periodontal health. For a randomized controlled trial, researchers recruited 39 older adults with chronic periodontitis, including one or more periodontal pockets measuring at least 4 mm. Subjects took 50 mg of heat-treated

Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 or a placebo for 12 weeks. Both groups also underwent standard periodontal therapy. The postbiotic group showed a 64% greater reduction in pocket depth than the placebo group [

28].

Lactobacillus plantarum produces organic acids, plantaricins, exopolysaccharides, and immune-modulating molecules that enhance oral microbiome balance, inhibit pathogens, and support gingival and dental health [

29]. Also, being a postbiotic, you get the beneficial effects on periodontal health without live fermentation, so the lactobacilli do not significantly lower oral pH.

Actionable step: Take a lozenge containing both S. salivarius M18 (prebiotic) and L. plantarum L-137 (postbiotic) at night after brushing and flossing. Salivary flow is reduced during sleep giving the compounds more contact time. Let dissolve slowly without chewing for maximum local exposure.

3.9. Tongue Scraping

Regular tongue scraping helps optimize the oral habitat of nitrate-reducing bacteria which are critical players in the enterosalivary nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway. Metagenomic analysis of tongue-scraping samples identified several bacterial species capable of reducing nitrate to nitrite thereby forming the substrate for NO synthesis and thereby contributing to vascular NO homeostasis suggesting that tongue scraping, by managing the tongue microbiome, supports NO production and may positively impact resting blood pressure [

23].

Beyond systemic vascular benefits, tongue scraping provides tangible oral health advantages. In a randomized controlled trial involving gingivitis patients, those who performed tongue scraping showed significant reductions in volatile sulfur compounds (halitosis indicators), tongue coating, and gingival crevicular fluid levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-8; effects not seen in patients who only received general oral hygiene instruction [

30]. Furthermore, systematic reviews underscore the role of the tongue dorsum as a reservoir for bacteria involved in bad breath and dental disease, and many clinical studies report that mechanical cleaning (e.g., scraping) effectively reduces coating and odor-causing microbes [

31].

In summary, peer-reviewed research supports that tongue scraping fosters a healthier oral microbial composition by enhancing the abundance and activity of nitrate-reducing bacteria facilitating NO production. Simultaneously, mechanical removal of tongue biofilm improves halitosis, reduces inflammatory markers, and may curb pathogens that contribute to periodontal disease and tooth decay.

Actionable step: Scrape tongue with either a metal or plastic scraper first thing in the morning to remove biofilm that accumulated overnight. Position the scraper at the back of the tongue. Use 5–10 scrapes with light pressure, rinsing scraper with each pass until the surface is clean. When finished, clean scraper and air dry to prevent bacterial build-up.

3.10. Emerging Tools

Emerging technologies are reshaping preventive dentistry. Nanotechnology provides antimicrobial delivery systems and bioactive materials that disrupt biofilms and promote remineralization [

25]. Salivary diagnostics enable quick, noninvasive detection of biomarkers such as CRP, Aβ peptides, and periodontal pathogens [

2].

An artificial intelligence–based system integrates intraoral scans with cone-beam computed tomography to quantify gingiva–bone distances and visualize periodontal destruction, thereby enhancing individualized assessment and prognosis of bone loss [

32]. Such approaches allow clinicians to target interventions proactively rather than reactively. Together, these tools support precision oral-systemic care, allowing earlier detection and targeted prevention of inflammatory disease.

Actionable step: Support development and clinical adoption of salivary diagnostics and AI-based risk tools in addition to traditional preventive strategies. Key preventive strategies are summarized in

Table 1.

4. Future Directions and Research Gaps

Oral health is an evolving field like any other field of science. In recent history it has become accepted that oral health has effects on the body as a whole. There are many studies showing that oral resident bacteria is found in other parts of the body such as P. Gingivalis in the brain and in atherosclerotic plaque; however, there is little evidence to support a mechanism of action. Many theories have been proposed, yet there isn’t sufficient evidence to support them. In the future, mechanistic studies and clinical trials are necessary in order to establish a mechanism of action because only after you understand a disease, can you work on a prevention.

Establishing good oral habits at a young age is important for keeping a healthy oral cavity over an extended period of time. Studies have shown that as you age, your likelihood of developing moderate periodontitis increases significantly. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the prevalence and severity of periodontitis increase significantly with age. Establishing and maintaining effective oral hygiene practices early in life is therefore essential to preserve periodontal health and reduce disease risk in later years.

Systemic effects of periodontitis are widely accepted, but the mechanisms of these effects are alarmingly unknown. It is a complex disease process; therefore, interhealthcare collaboration in dentistry, cardiology, neurology, etc., is needed to understand the complex nature of these effects. Each healthcare professional can lend their expertise in their respective area. Establishing an understanding of these disease processes will allow for the prevention in the future.

5. Conclusions

This narrative review supports the central hypothesis that oral health is not merely a local concern but a modifiable upstream determinant in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease and atherosclerosis. Mechanistic evidence consistently shows that oral pathogens and chronic periodontal inflammation can drive neuroinflammation, BBB disruption, vascular injury, and endothelial dysfunction. These processes overlap in Alzheimer’s disease and atherosclerosis, suggesting that interventions aimed at improving oral hygiene have the potential to mitigate both cognitive decline and vascular risk.

Recent large-scale observational and systematic reviews have strengthened this association. For example, a study using over 30 million medical records found that poor oral health was associated with more than twice the risk of AD compared to individuals with healthy oral status [

6]. Similarly, “Oral Health as a Risk Factor for Alzheimer Disease,” a 2024 systematic review, identified possible causal links between periodontal disease and Alzheimer’s via pathogens, inflammatory mediators, APOE genotypes, and amyloid-β pathways [

8]. These findings underscore that oral health should be viewed among modifiable risk factors like hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

For clinicians, the practical takeaway is that routine periodontal assessment and management should be integrated into risk reduction strategies for both AD and cardiovascular disease. This includes screening for periodontal disease, ensuring patients maintain effective plaque control (brushing, interdental cleaning), considering professional periodontal therapy when indicated, and partnering with dental specialists. Such preventive care is low-risk, widely accessible, and may delay or reduce burden of neurodegenerative and vascular disease. Future research should aim for interventional trials to quantify the degree to which improving oral health reduces Alzheimer’s or atherosclerosis incidence and progression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.L. and C.W.; methodology, J.B.L. and C.W.; validation, J.T. and G.H.; formal analysis, J.B.L.; data curation, R.M., J.B.L. and C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.L., C.W. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, J.T. and G.H.; visualization, J.B.L., C.W. and J.T.; supervision, J.B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article is a narrative review and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors; therefore, Institutional Review Board approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dewhirst, F.E.; Chen, T.; Izard, J.; Paster, B.J.; Tanner, A.C.R.; Yu, W.H.; Lakshmanan, A.; Wade, W.G. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 5002–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Periodontology (AAP). Periodontal Disease Overview. Available online: https://www.perio.org/for-patients/gum-disease-information/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Huang, X.; Xie, M.; Lu, X.; Mei, F.; Song, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L. The Roles of Periodontal Bacteria in Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Martínez, V.; Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J.; Pecci-Lloret, M.P.; Pérez-Guzmán, N. Association Between Oral Dysbiosis and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.S.; Miller, B.C.; Mahani, M.; Mhaskar, R.; Tsalatsanis, A.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Poor Oral Health Linked with Higher Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, F. Periodontitis-induced neuroinflammation triggers IFITM3-Aβ axis to cause Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology and cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruntel, S.M.; van Munster, B.C.; de Vries, J.J.; Vissink, A.; Visser, A. Oral Health as a Risk Factor for Alzheimer Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 11, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaple-Gil, A.M.; Santiesteban-Velázquez, M.; Urbizo Vélez, J.J. Association Between Oral Microbiota Dysbiosis and the Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominy, S.S.; Lynch, C.; Ermini, F.; Benedyk, M.; Marczyk, A.; Konradi, A.; Nguyen, M.; Haditsch, U.; Raha, D.; Griffin, C.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsakis, G.A.; Lian, Q.; Ioannou, A.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; John, M.T.; Chu, H. A network meta-analysis of interproximal oral hygiene methods in the reduction of clinical indices of inflammation. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungare, S.; Paranjpe, A.G. Diet and Nutrition to Prevent Dental Problems. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M. Sugar Substitutes: Mechanism, Availability, Current Use and Safety Concerns—An Update. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1888–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Issues Recommendations for Certain High-Risk Groups Regarding Mercury-Containing Dental Amalgam; US Food & Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Mercury in Dental Amalgam; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, N.; Bastiansz, A.; Dórea, J.G.; Fujimura, M.; Horvat, M.; Shroff, E.; Weihe, P.; Zastenskaya, I. Our evolved understanding of the human health risks of mercury. Ambio 2023, 52, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, H.V.; Khangura, S.; Seal, K.; Mierzwinski-Urban, M.; Veitz-Keenan, A.; Sahrmann, P.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Davis, D.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Rasines Alcaraz, M.G. Direct composite resin fillings versus amalgam fillings for permanent posterior teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021, 8, CD005620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kall, J. The Safe Mercury Amalgam Removal Technique (SMART); International Academy of Oral Medicine and Toxicology (IAOMT): Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Su, N.; Marek, C.L.; Ching, V.; Grushka, M. Caries prevention for patients with dry mouth. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 77, b85. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, C.E.; Silva-Acevedo, C.A.; Padilla-Orellana, F.; Zero, D.; Carvalho, T.S.; Lussi, A. Should We Wait to Brush Our Teeth? A Scoping Review Regarding Dental Caries and Erosive Tooth Wear. Caries Res. 2024, 58, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Dental Association. Available online: https://www.ada.org (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Bondonno, C.P.; Liu, A.H.; Croft, K.D.; Considine, M.J.; Puddey, I.B.; Woodman, R.J.; Hodgson, J.M. Antibacterial mouthwash blunts oral nitrate reduction and increases blood pressure in treated hypertensive men and women. Am. J. Hypertens. 2015, 28, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribble, G.D.; Angelov, N.; Weltman, R.; Wang, B.Y.; Eswaran, S.V.; Gay, I.C.; Parthasarathy, K.; Dao, D.V.; Richardson, K.N.; Ismail, N.M.; et al. Frequency of Tongue Cleaning Impacts the Human Tongue Microbiome Composition and Enterosalivary Circulation of Nitrate. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woessner, M.; Smoliga, J.M.; Tarzia, B.; Stabler, T.; Van Bruggen, M.; Allen, J.D. A stepwise reduction in plasma and salivary nitrite with increasing strengths of mouthwash following a dietary nitrate load. Nitric Oxide 2016, 54, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Cao, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Ye, X.; Zou, J.; et al. Competitive dynamics and balance between Streptococcus mutans and commensal streptococci in oral microecology. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 51, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, K.; Salikhova, D.; Doroshina, V.; Makeeva, I.; Zaytsev, A.; Uvarichev, M.; Polyakova, M.; Novozhilova, N. Antigingivitis and Antiplaque Effects of Oral. Probiotic Containing the Streptococcus salivarius M18 Strain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, K.; Salikhova, D.; Makeeva, I.; Zaytsev, A.; Sokhova, I.; Musaeva, S.; Polyakova, M.; Novozhilova, N. A Three-Month Probiotic (the Streptococcus salivarius M18 Strain) Supplementation Decreases Gingival Bleeding and Plaque Accumulation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, K.; Maeda, K.; Hidaka, K.; Nemoto, K.; Hirose, Y.; Deguchi, S. Daily Intake of Heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 Decreases the Probing Depth in Patients Undergoing Supportive Periodontal Therapy. Oral. Health Prev. Dent. 2016, 14, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, D.; Angamarca, E.; Marinescu, G.C.; Popescu, R.G.; Tenea, G.N. Integrating Metabolomics and Genomics to Uncover Antimicrobial Compounds in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum UTNGt2, a Cacao-Originating Probiotic from Ecuador. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, B.; Berker, E.; Tan, Ç.; İlarslan, Y.D.; Tekçiçek, M.; Tezcan, İ. Effects of oral prophylaxis including tongue cleaning on halitosis and gingival inflammation in gingivitis patients-a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2019, 23, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blot, S. Antiseptic mouthwash, the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway, and hospital mortality: A hypothesis-generating review. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Tsoi, J.K.H. AI-powered digital probing improves periodontal disease diagnosis. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).