StartXFit—Nine Months of CrossFit® Intervention Enhance Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Well-Being in CrossFit Beginners

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

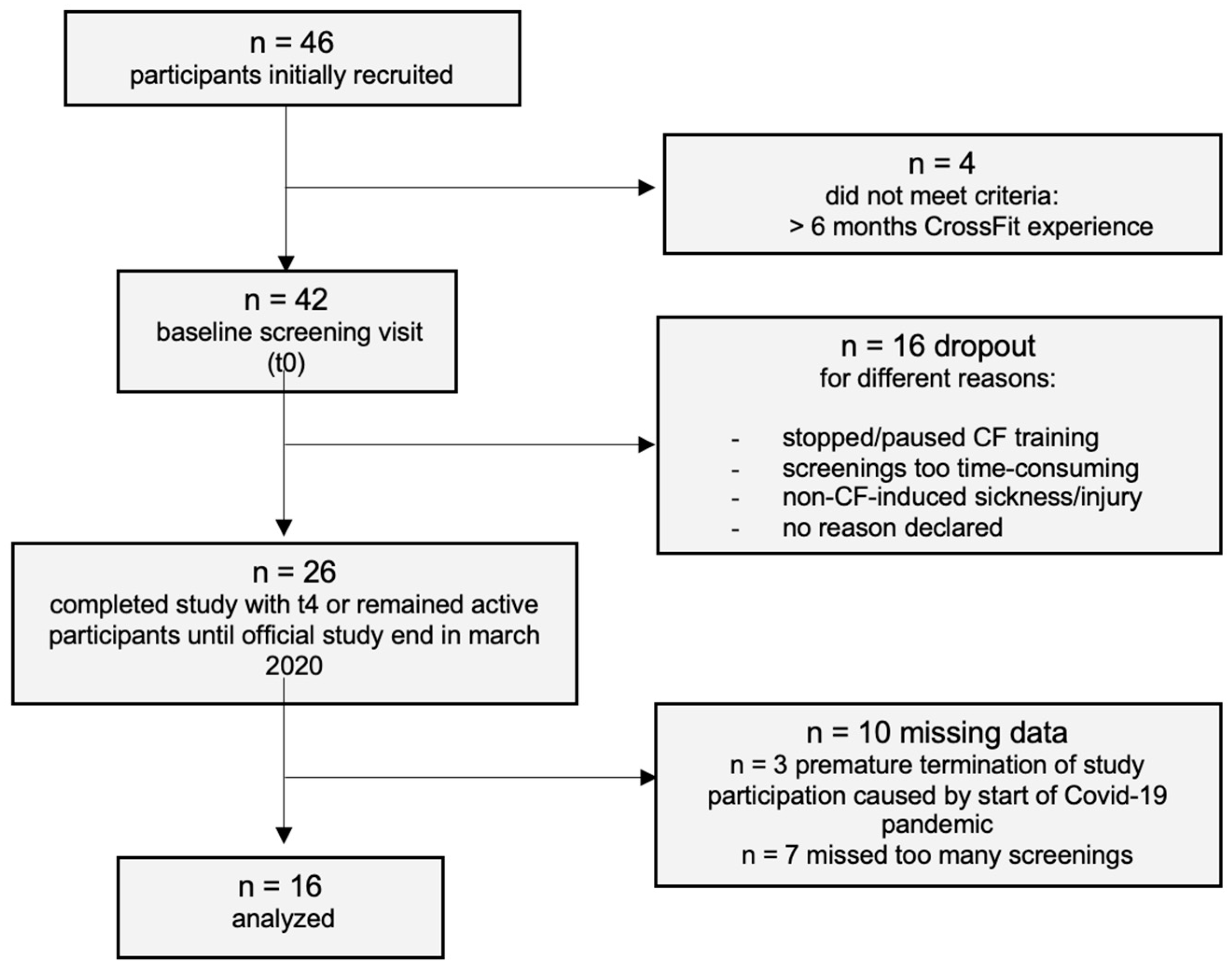

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Endpoints

2.4. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET)

2.5. Well-Being

2.6. Body Composition

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

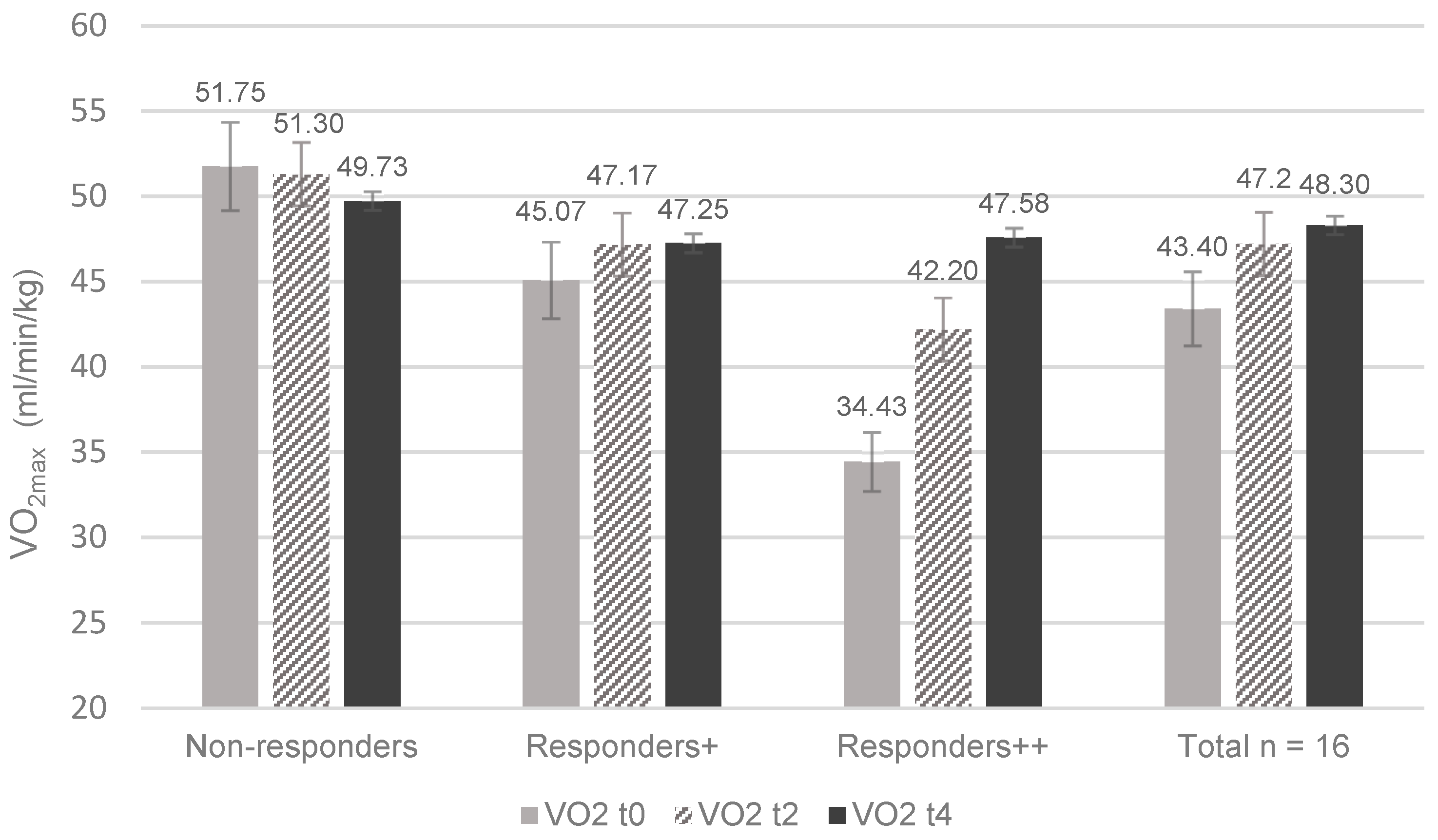

3.2. Primary Endpoint VO2max

3.3. Secondary Endpoint Well-Being

3.4. Exploratory

4. Discussion

4.1. Primary Endpoint—VO2max

4.2. Secondary Endpoint—Well-Being

4.3. Exploratory

4.4. Group-Based Analysis Categorized by Bodyfat

4.5. Risk of Bias, Dropout, and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. CrossFit

Appendix A.2. Statistical Power

Appendix B

| All Participants (n = 46) | Males (n = 29) | Females (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 63 | ||

| Female (%) | 36 | ||

| Age (y) | 33.8 ± 8.1 | 35.1 ± 7.3 | 31.5 ± 9 |

| Height (cm) | 177.2 ± 9.2 | 182.1 ± 7.2 | 168.8 ± 5.4 |

| Weight (kg) | 80.1 ± 17.8 | 89.1 ± 15.6 | 64.8 ± 8.5 |

| Body fat (%) | 23.1 ± 7.2 | 20.8 ± 6.5 | 27.0 ± 6.8 |

| Muscle mass (%) | 73.0 ± 6.9 | 75.3 ± 6.2 | 69.2 ± 6.4 |

| Resting metabolic rate (kcal) | 1819.1 ± 378.9 | 2056.3 ± 260.4 | 1414.4 ± 95.6 |

| Current smoker (%) | 6.5 (n = 3) | ||

| Sedentary occupation (%) | 93.5 (n = 43) |

| t0 (n = 16) | t4 (n = 14) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CrossFit: sessions/week | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 0.002 * |

| Hours per CrossFit session (h) | 1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.168 |

| Practicing other sport (%) | 75 (n = 12) | 62.5 (n = 10) | |

| Practicing endurance sports (%) | 56.3 (n = 9) | 43.8 (n = 7) | |

| Other sports: sessions/week | 1 ± 1.4 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | |

| Hours per other training session (h) | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | |

| Practiced sports as child/adolescent (%) | 87.5 (n = 14) | ||

| Childhood sports sessions/week | 3.6 ± 1.3 |

| n | Chi-Square | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO2max (mL/min/kg) | 16 | 7.63 | 0.022 * |

| df | Chi-Square | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 16 | 2.41 | 0.662 |

| Body fat (%) | 16 | 2.20 | 0.699 |

| Muscle mass (%) | 16 | 2.33 | 0.675 |

| Basal metabolism (kcal) | 12 | 13.64 | 0.009 * |

| Resting heart rate (bpm) | 16 | 0.61 | 0.962 |

References

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health. 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, J.D.; Mensink, G.; Lange, C.; Manz, K. Arbeitsbezogene Körperliche Aktivität bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland Journal of Health Monitoring Arbeitsbezogene körperliche Aktivität bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland. Robert Koch Institute. 2017. Available online: www.geda-studie.de (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Ammar, A.; Brach, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on physical activity and eating behaviour Preliminary results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online-survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheval, B.; Sivaramakrishnan, H.; Maltagliati, S.; Fessler, L.; Forester, C.; Sarrazin, P.; Orsholits, D.; Chalabaev, A.; Sander, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; et al. Relationships Between Changes in Self-Reported Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviours and Health During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in France and Switzerland. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Bize, R.; Johnson, J.A.; Plotnikoff, R.C. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Leslie, E.; Sugiyama, T.; Owen, N. Associations of multiple physical activity domains with mental well-being. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2009, 2, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.; Kearns, A. Physical activity and mental wellbeing in deprived neighbourhoods. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2013, 6, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mallah, M.H.; Sakr, S.; Al-Qunaibet, A. Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: An Update. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2018, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Blair, S.N.; Arena, R.; Church, T.S.; Després, J.P.; Franklin, B.A.; Haskell, W.K.; Kaminsky, L.A.; Levine, B.D.; Lavie, C.J.; et al. Importance of Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Clinical Practice: A Case for Fitness as a Clinical Vital Sign: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134, e653–e699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.C.; Pate, R.R.; Lavie, C.J.; Sui, X.; Church, T.S.; Blair, S.N. Leisure-Time Running Reduces All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, H.; Loenneke, J.P.; Thiebaud, R.S.; Abe, T. Resistance training induced increase in VO2max in young and older subjects. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Cai, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, L.; Zuegel, M.; Steinacker, J.M.; Schumann, U. Heart Rate Recovery and Risk of Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peçanha, T.; Silva-Júnior, N.D.; de Forjaz, C.L.M. Heart rate recovery: Autonomic determinants, methods of assessment and association with mortality and cardiovascular diseases. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2014, 34, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, J.J.; Le, F.K.; Lahiri, M.; Kannankeril, P.J.; Ng, J.; Kadish, A.H. Assessment of parasympathetic reactivation after exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H2446–H2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, S.; Haugen, O.; Kufel, E. Autonomic Recovery after Exercise in Trained Athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coote, J.H. Recovery of heart rate following intense dynamic exercise. Exp. Physiol. 2010, 95, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassmann, G. Level 1 Training Guide—CrossFit Training. 2020. Available online: http://library.crossfit.com/free/pdf/CFJ_English_Level1_TrainingGuide.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- McKenzie, M.J. Crossfit Improves Measures of Muscular Strength and Power in Active Young Females. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, S.J.; Crawford, D.A.; Heinrich, K.M. Multiple fitness improvements found after 6-months of high intensity functional training. Sports 2019, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawska-Cialowicz, E.; Wojna, J.; Zuwala-Jagiello, J. Crossfit training changes brain-derived neurotrophic factor and irisin levels at rest, after Wingate and progressive tests, and improves aerobic capacity and body composition of young physically active men and women. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 66, 811–821. [Google Scholar]

- Cavedon, V.; Milanese, C.; Marchi, A.; Zancanaro, C. Different amount of training affects body composition and performance in High-Intensity Functional Training participants. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrero, G.L.; Inman, C.; Stone, W.; Zagdsuren, B.; Arnett, S.W.; Shafer, M.A.; Lyons, S.; Maples, J.M.; Crandall, J.; Callahan, Z. Crossfit vs. Circuit-trained Individuals. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Schmidt, A.; Schinköthe, T.; Heinz, E.; Klaaßen, Y.; Limbara, S.; Morsdorf, M. MedXFit—Effects of 6 months CrossFit® in sedentary and inactive employees: A prospective, controlled, longitudinal, intervention study. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino, J.G.; Gabbett, T.J.; Bourgeois, F.; de Souza, H.S.; Miranda, R.C.; Mezêncio, B.; Soncin, R.; Filho, C.A.C.; Bottaro, M.; Hernandez, A.J.; et al. CrossFit Overview: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, P.; Cimadevilla, E.; Guodemar-Pérez, J.; Cañuelo-Márquez, A.M.; Heredia-Elvar, J.R.; Fernández-Rodríguez, T.; Lozano-Estevan, M.D.C.; Hervaz-Perez, J.P.; Sanchez-Calabuig, M.A.; Garnacho-Castano, M.V.; et al. Muscle Recovery after a Single Bout of Functional Fitness Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkalec-Michalski, K.; Nowaczyk, P.M.; Siedzik, K. Effect of a four-week ketogenic diet on exercise metabolism in CrossFit-trained athletes. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2019, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkalec-Michalski, K.; Domagalski, A.; Główka, N.; Kamińska, J.; Szymczak, D.; Podgórski, T. Effect of a Four-Week Vegan Diet on Performance, Training Efficiency and Blood Biochemical Indices in CrossFit-Trained Participants. Nutrients 2022, 14, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, N.; Sietmann, D.; Schmidt, A. Comparison of Cardiovascular Parameters and Internal Training Load of Different 1-h Training Sessions in Non-elite CrossFit® Athletes. J. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2022, 5, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, F.; Aidar, A.; Souza, R.F.; Matos, D.; Ferreira, A.R.P. Evaluation of a CrossFit® Session on Post-Exercise Blood Pressure. J. Exerc. Physiol. Online 2018, 21, 44–51. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322917373 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Fogaça, L.J.; Santos, S.L.; Soares, R.C.; Gentil, P.; Naves, J.P.; dos Santos, W.D.; Pimentel, G.; Bottaro, M.; Mota, J.F. Effect of caffeine supplementation on exercise performance, power, markers of muscle damage, and perceived exertion in trained CrossFit men: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2020, 60, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Henschel, B.; Gorczyca, A.M.; Chomistek, A.K. Time Spent Sitting as an Independent Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 14, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straker, L.; Coenen, P.; Dunstan, D.; Gilson, N.; Healy, G. Sedentary Work—Evidence on an Emergent Work Health and Safety Issue—Final Report. Safe Work Australia; 2016. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-03/literature-review-of-the-hazards-of-sedentary-work%202.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Helgerud, J.; Høydal, K.; Wang, E.; Karlsen, T.; Berg, P.; Bjerkaas, M.; Simonsen, T.; Helgesen, C.; Hjorth, N.; Bach, R.; et al. Aerobic High-Intensity Intervals Improve VO2max More Than Moderate Training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, D.; Drake, N.; Carper, M.; DeBlauw, J.; Heinrich, K. Are Changes in Physical Work. Capacity Induced by High-Intensity Functional Training Related to Changes in Associated Physiologic Measures? Sports 2018, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, K.M.; Patel, P.M.; O’Neal, J.L.; Heinrich, B.S. High-intensity compared to moderate-intensity training for exercise initiation, enjoyment, adherence, and intentions: An intervention study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman-Sandland, J.; Hawkins, J.; Clayton, D. The role of social capital and community belongingness for exercise adherence: An exploratory study of the CrossFit gym model. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straker, L.M.; Leon, M.; Coenen, P.; Dunstan, D.W.; Gilson, N.; Healy, G.; Safe Work Australia. Sedentary Work: Evidence on an Emergent Work Health and Safety Issue. 61p. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43390556.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Bengoechea García, E.; Pedisic, Z.; Bennie, J.; Vergeer, I.; Wiesner, G. Screen Time, Other Sedentary Behaviours, and Obesity Risk in Adults: A Review of Reviews. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Courtney, T.K.; Lombardi, D.A.; Verma, S.K. Association Between Sedentary Work and BMI in a U.S. National Longitudinal Survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, e117–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.M.; Sommer, A.J.; Starkoff, B.E.; Devor, S.T. Crossfit-Based High-Intensity Power Training Improves Maximal Aerobic Fitness and Body Composition. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 3159–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health & Human Services. Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Brisebois, M.; Rigby, B.; Nichols, D. Physiological and Fitness Adaptations after Eight Weeks of High-Intensity Functional Training in Physically Inactive Adults. Sports 2018, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griban, G.; Zhembrovskyi, S.; Yahodzinskyi, V.; Fedorchenko, T.; Viknianskyi, V.; Tkachenko, P.; Samolenko, T.; Malynoshevskyi, R.; Solohubova, S.; Otravenko, O.; et al. Characteristics of Morphofunctional State of Paratrooper Cadets in the Process of CrossFit Training. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sports Sci. 2021, 9, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Steeg, G.E.; Takken, T. Reference values for maximum oxygen uptake relative to body mass in Dutch/Flemish subjects aged 6–65 years: The LowLands Fitness Registry. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 121, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierpont, G.L.; Voth, E.J. Assessing autonomic function by analysis of heart rate recovery from exercise in healthy subjects. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004, 94, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javorka, M.; Zila, I.; Balhárek, T.; Javorka, K. Heart rate recovery after exercise: Relations to heart rate variability and complexity. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2002, 35, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, B.H.; Williams, D.M.; Dubbert, P.M.; Sallis, J.F.; King, A.C.; Yancey, A.K.; Franklin, B.A.; Buchner, D.; Daniels, S.R.; Claytor, R.P.; et al. Physical Activity Intervention Studies. Circulation 2006, 114, 2739–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Participants (n = 16) | Males (n = 14) | Females (n = 2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 87.5 | ||

| Female (%) | 12.5 | ||

| Age (y) | 35 ± 6.8 | 36 ± 6.4 | 28 ± 7.1 |

| Height (cm) | 180.6 ± 8.6 | 182.9 ± 5.9 | 164.0 ± 5.7 |

| Weight (kg) | 85.5 ± 19.1 | 88.6 ± 18.3 | 66.1 ± 4.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 4.6 | 26.3 ± 4.8 | 24.7 ± 3.3 |

| Body fat (%) | 21.1 ± 7.2 | 20.4 ± 7.4 | 26.3 ± 0.4 |

| Muscle mass (%) | 75.0 ± 6.8 | 75.7 ± 7 | 69.9 ± 0.3 |

| Resting metabolic rate (kcal) | 1962.3 ± 321.1 | 2032.7 ± 274.3 | 1469.0 ± 110.3 |

| Resting heart rate (bpm) | 65.9 ± 9.6 | ||

| Current smoker (%) | 6.3 (n = 1) | ||

| Sedentary occupation (%) | 100 (n = 16) |

| n | t0 | t2 | t4 | Difference | ANOVA | ||

| M [95% CI] | M [95% CI] | M [95% CI] | t0–t4 | p | |||

| VO2max (mL/min/kg) | 16 | 43.3 [37.6, 49.1] | 47.2 [42.2, 52.1] | 48.3 [43.9, 52.7] | 5 [0.1, 9.7] | 0.008 * | 0.27 |

| Wattage max (W) | 16 | 275.2 [243.7, 306.8] | 275.0 [249.5, 300.5] | 276.4 [238.8, 313.9] | 0.4 [−15.3, 16.0] | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| Watt/kg max | 16 | 3.3 [2.9, 3.8] | 3.3 [2.9, 3.8] | 3.3 [2.8, 3.8] | −0.1 [−0.3, 0.2] | 1.000 | 0.01 |

| HR max (bpm) | 16 | 173.6 [164.5, 182.8] | 174.3 [163.9, 184.7] | 171.9 [159.4, 184.4] | 1.1 [−4.1, 6.3] | 1.000 | 0.07 |

| HRR 1 min (bpm) | 16 | 143.8 [135.8, 151.9] | 142.1 [129.5, 154.7] | 132.1 [120.2, 144.0] | 11.7 [−10.9, 14.3] | 0.040 * | 0.34 |

| HRR 5 min (bpm) | 16 | 114.5 [107.6, 121.3] | 110.9 [102.1, 119.8] | 106.5 [97.6, 115.5] | 7.9 [0.0, 15.8] | 0.049 * | 0.27 |

| n | t0 | t4 | Difference | t-test | |||

| M [95% CI] | M [95% CI] | t0–t4 | p | d | |||

| Well-being (%) | 16 | 60.5 [52.2, 67.9] | 69.2 [61.1, 76.9] | 8.7 [2.4, 15] | 0.005 * | 0.59 | |

| t0 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | Difference | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M [95% CI] | M [95% CI] | M [95% CI] | M [95% CI] | M [95% CI] | t0–t4 | p | ||

| Weight (kg) | 85.5 [75.3, 95.7] | 85.9 [76, 95.8] | 85.2 [75.7, 94.7] | 85.3 [76.2, 94.5] | 83.9 [76.8, 91.1] | −1.6 [−8.4, 11.6] | 0.617 | 0.02 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 [23.6, 28.5] | 26.2 [23.8, 28.7] | 26 [23.7, 28.4] | 26 [23.8, 28.2] | 25.8 [24.2, 27.4] | −0.3 [−1.4, 1.9] | 0.729 | 0.01 |

| Body fat (%) | 21.1 [17.3, 24.9] | 21.5 [17.4, 25.6] | 21.7 [17.6; 25.9] | 20.9 [17.2, 24.6] | 19.9 [16.2, 23.5] | −1.2 [−1.7, 4.2] | 0.296 | 0.08 |

| Muscle mass (%) | 75.0 [71.3, 78.6] | 74.6 [70.7, 78.5] | 74.3 [70.4, 78.3] | 75.2 [71.7, 78.6] | 76.2 [72.7, 79.7] | 1.2 [−4.1, 1.6] | 0.282 | 0.08 |

| RMR (kcal) | 1935.3 [1732, 2139] | 1934.7 [1737, 2133] | 1905.3 [1723, 2088] | 1942.1 [1756, 2128] | 1977.8 [1776, 2179] | 42.4 [−143.3, 58.4] | 0.042 * | 0.24 |

| Group 1 | t0 | t2 | t4 | Diff. | ANOVA | ||

| High bodyfat | n | M | M | M | t0–t4 | p | |

| VO2max (mL/min/kg) | 7 | 41.8 | 43.2 | 44.7 | –2.9 | 1.000 | –0.08 |

| Wattage max (W) | 7 | 289.3 | 285.7 | 282.0 | 7.2 | 1.000 | 0.06 |

| Wattage/kg max | 7 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 | –0.2 | 1.000 | 0.11 |

| HR max (bpm) | 7 | 168.7 | 168.7 | 164.1 | 4.6 | 0.271 | 0.31 |

| HRR 1 min (bpm) | 5 | 142.6 | 129.0 | 125.0 | 17.6 | 0.046 * | 0.62 |

| HRR 5 min (bpm) | 5 | 113.2 | 103.8 | 100.4 | 9.4 | 0.087 | 0.57 |

| Group 2 | t0 | t2 | t4 | Diff. | ANOVA | ||

| Low Bodyfat | n | M | M | M | t0–t4 | p | |

| VO2max (mL/min/kg) | 7 | 41.8 | 49.7 | 51.8 | –6.8 | 0.115 | 0.49 |

| Wattage max (W) | 7 | 269.6 | 268.6 | 275.8 | –6.2 | 1.000 | 0.07 |

| Wattage/kg max | 7 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 1.000 | 0.07 |

| HR max (bpm) | 7 | 176.7 | 178.0 | 177.7 | –1.0 | 1.000 | 0.02 |

| HRR 1 min (bpm) | 5 | 143.6 | 150.0 | 136.6 | 7.0 | 1.000 | 0.47 |

| HRR 5 min (bpm) | 5 | 114.0 | 116.6 | 109.8 | 4.2 | 1.000 | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schlie, J.; Brandt, T.; Schmidt, A. StartXFit—Nine Months of CrossFit® Intervention Enhance Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Well-Being in CrossFit Beginners. Physiologia 2023, 3, 494-509. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia3040036

Schlie J, Brandt T, Schmidt A. StartXFit—Nine Months of CrossFit® Intervention Enhance Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Well-Being in CrossFit Beginners. Physiologia. 2023; 3(4):494-509. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia3040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchlie, Jennifer, Tom Brandt, and Annette Schmidt. 2023. "StartXFit—Nine Months of CrossFit® Intervention Enhance Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Well-Being in CrossFit Beginners" Physiologia 3, no. 4: 494-509. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia3040036

APA StyleSchlie, J., Brandt, T., & Schmidt, A. (2023). StartXFit—Nine Months of CrossFit® Intervention Enhance Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Well-Being in CrossFit Beginners. Physiologia, 3(4), 494-509. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia3040036