Alcohol-Based Hand Rub Purchase as a Surrogate Marker for Monitoring Hand Hygiene in Nursing Homes: Results from a French Regional Survey over the 2018–2023 Period

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

- -

- Volume (L) of alcohol-based hand rub purchased in years n-1 and n-2 (year n being the year of the survey);

- -

- Status of the facility (private, public, associative or other);

- -

- Number of beds (year n);

- -

- Number of occupied bed days (year n);

- -

- Availability of an infection control link (ICL) nurse in the facility;

- -

- Availability of an IPC team for the facility.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

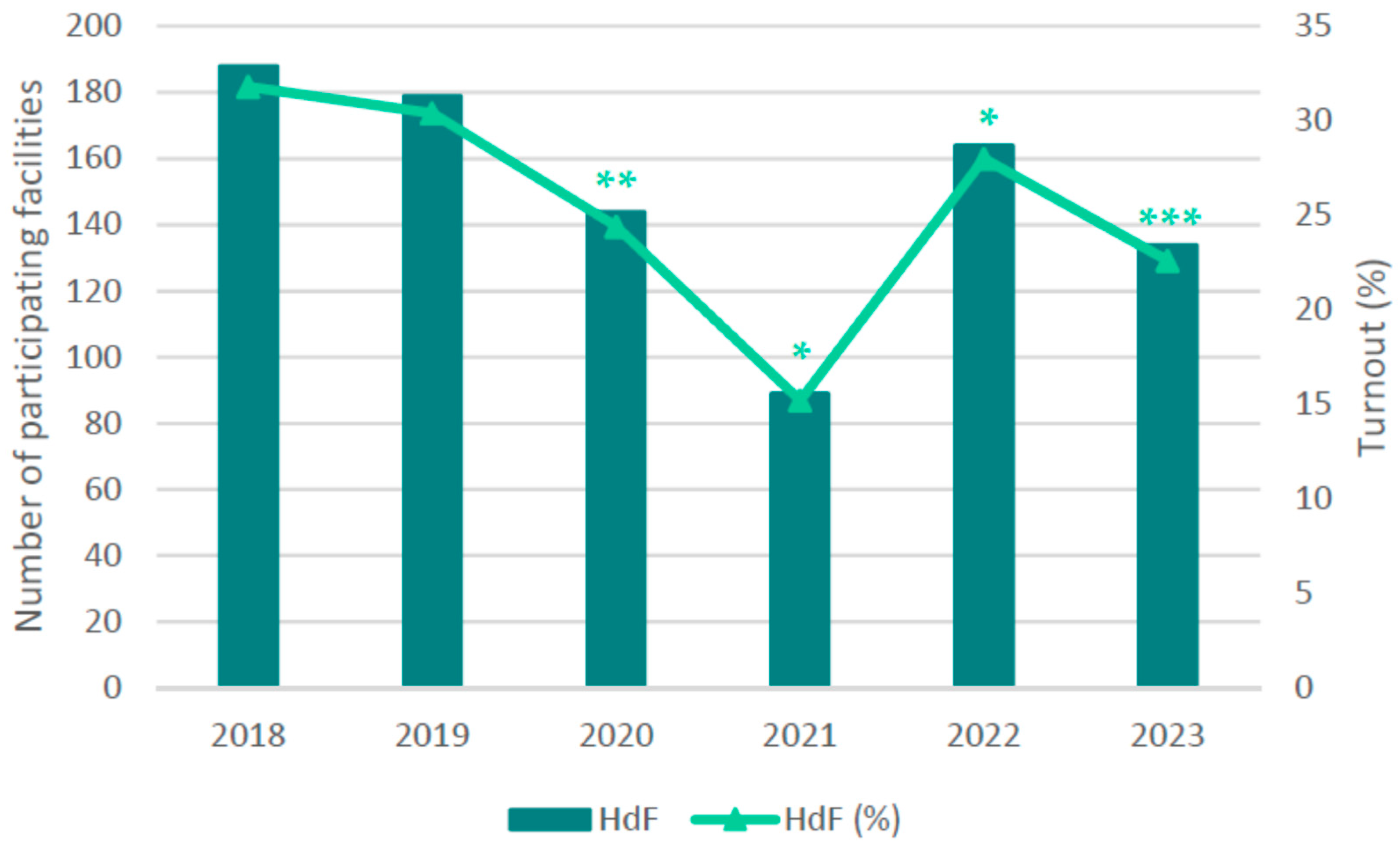

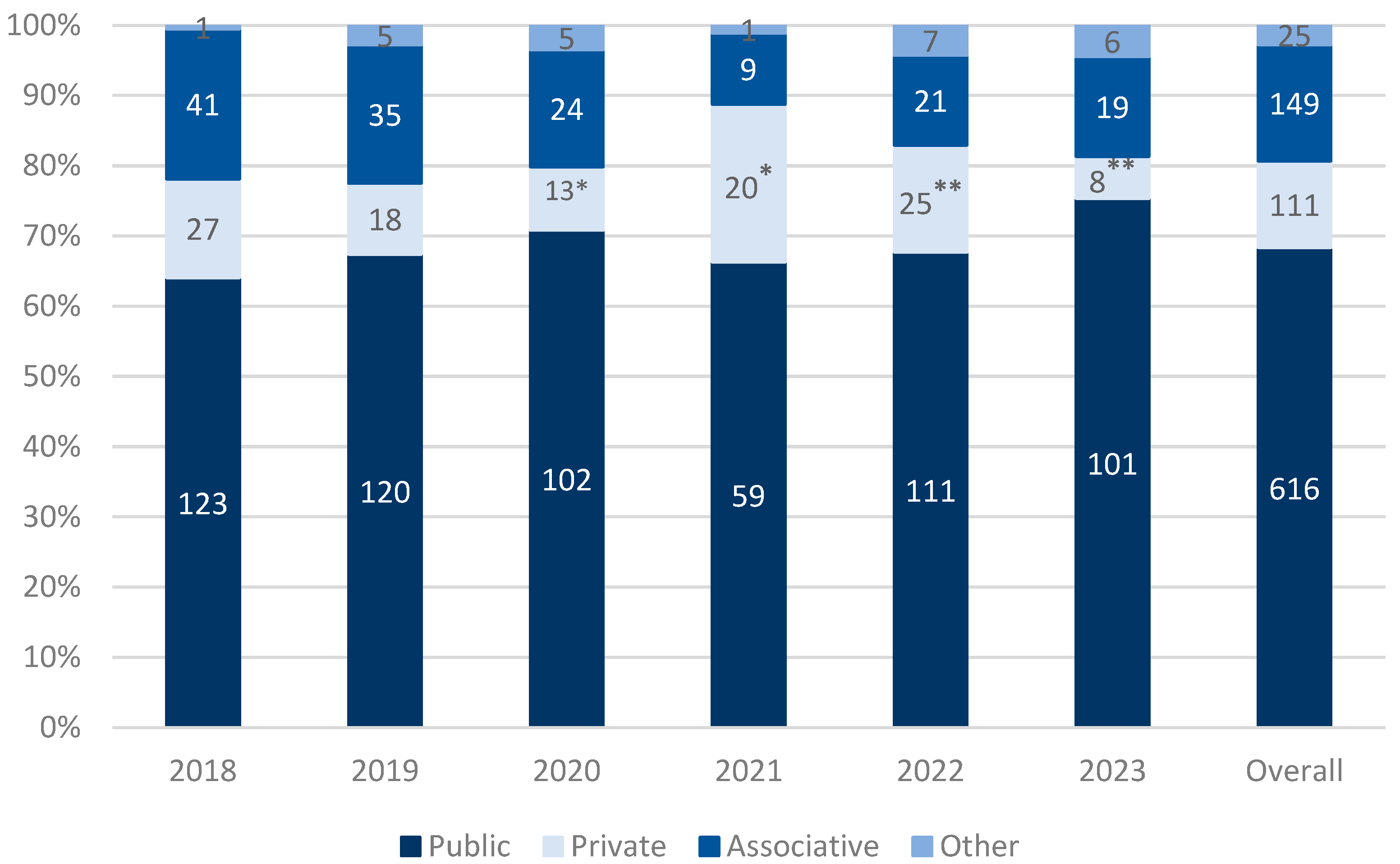

3.1. Participating Facilities and Their Characteristics

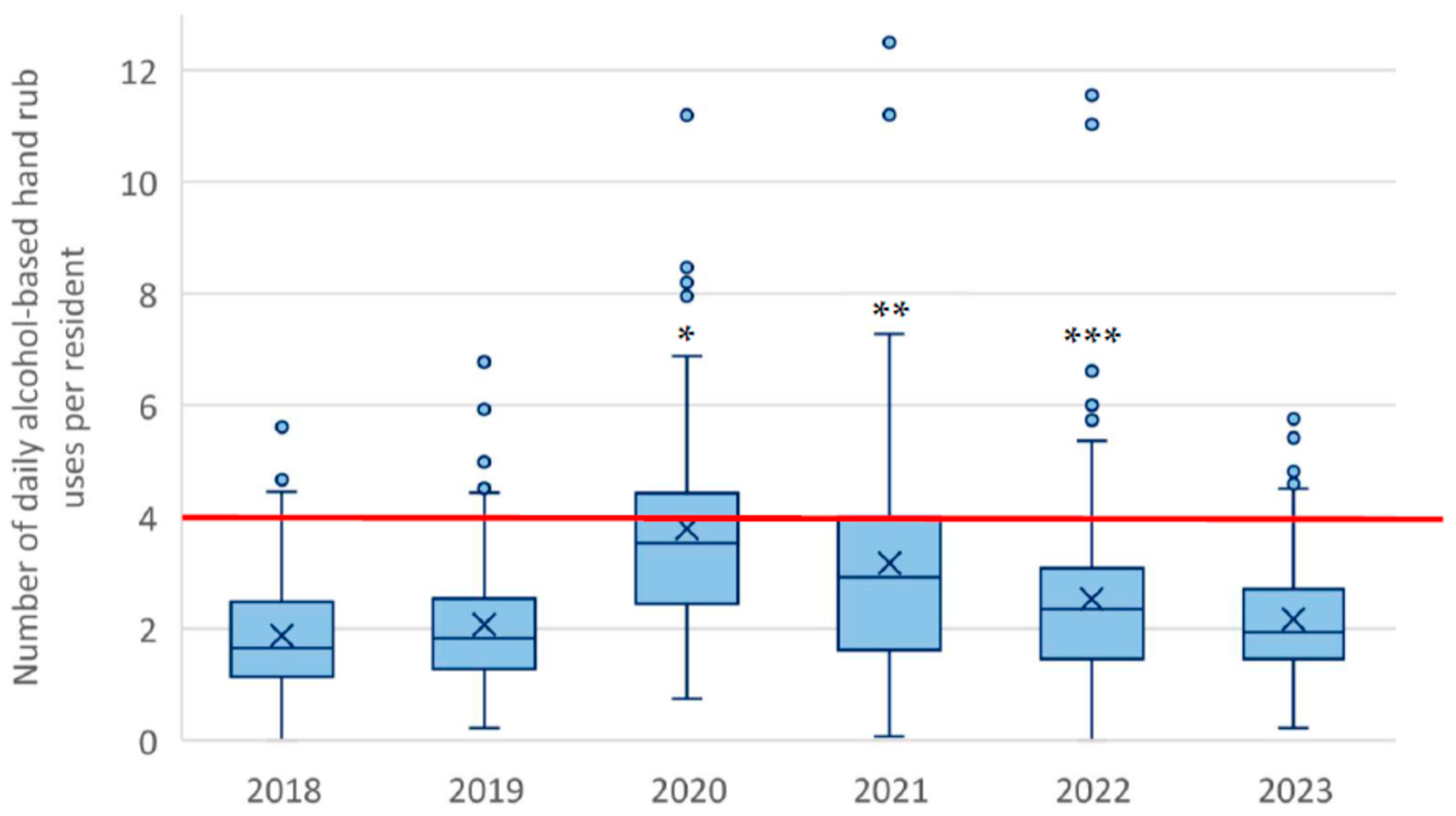

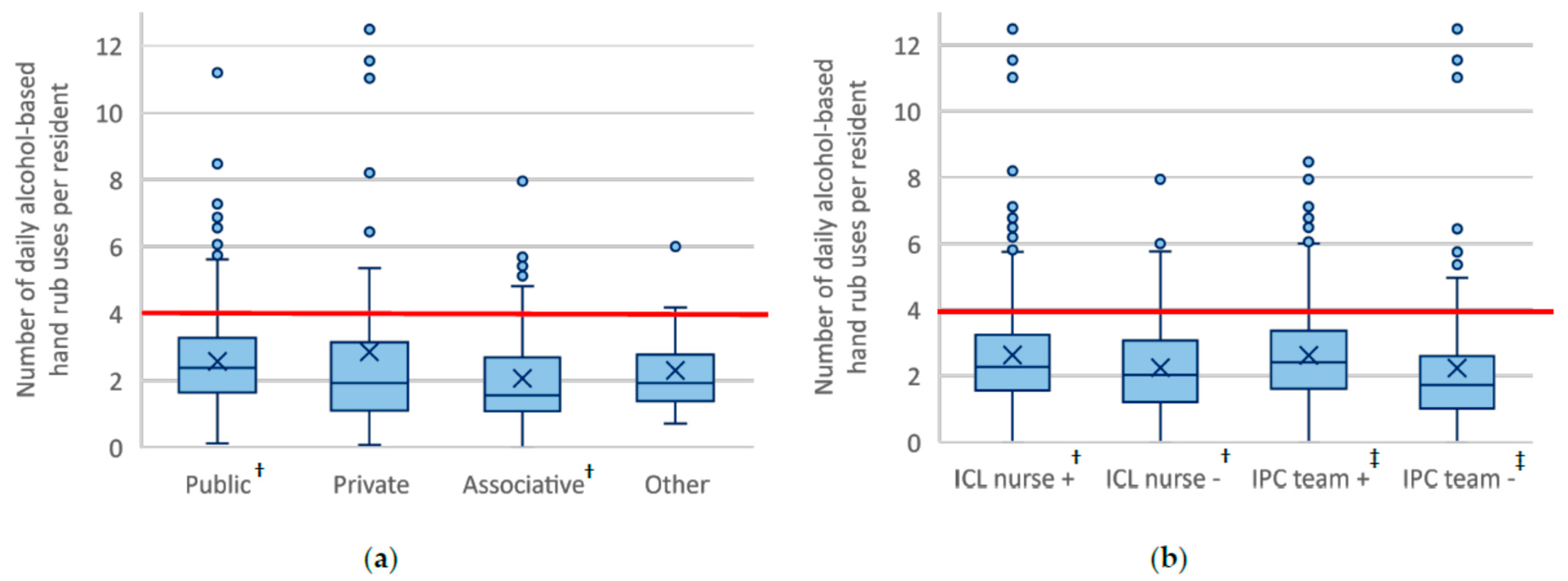

3.2. ABHR Indicator Analysis

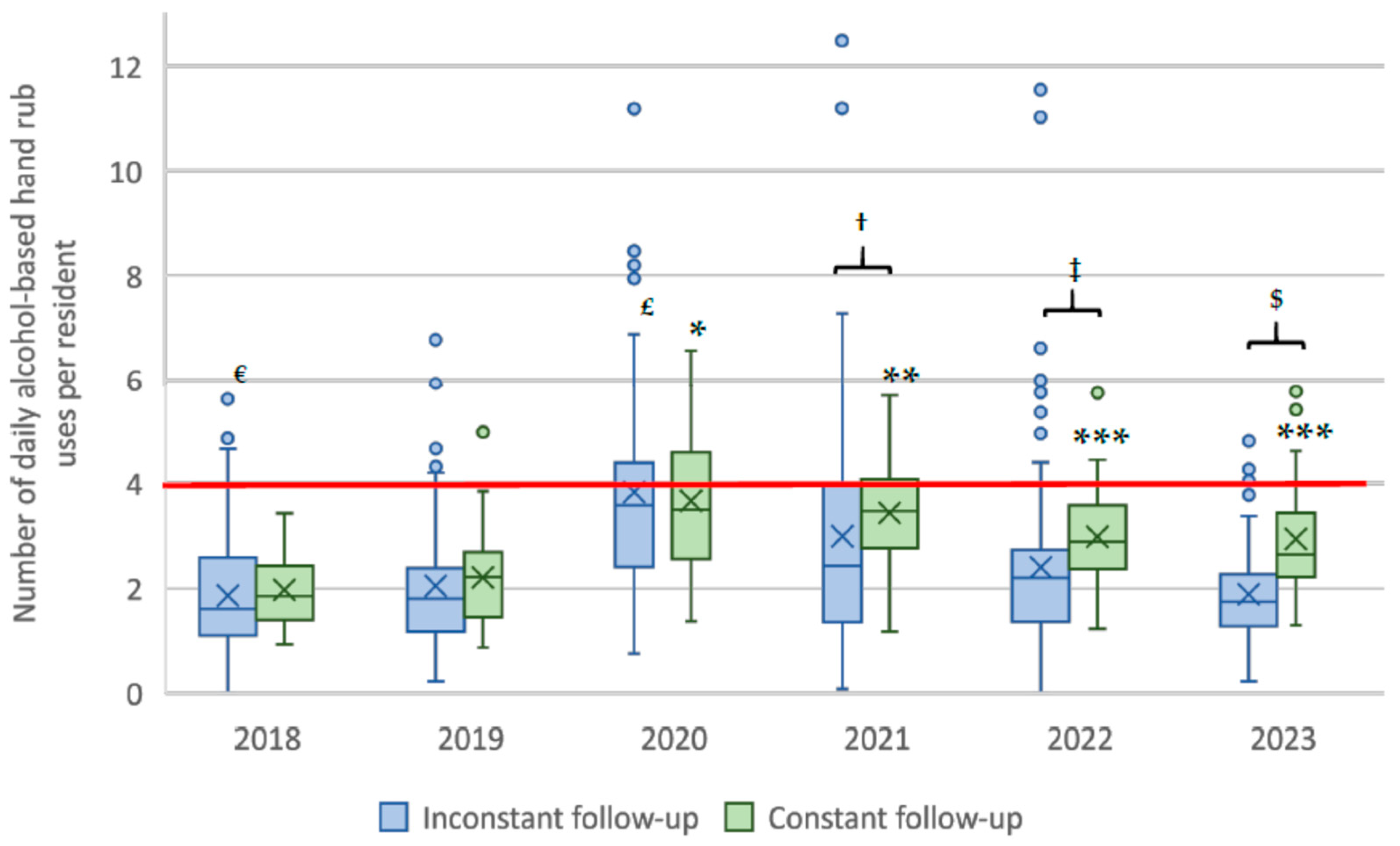

3.3. Constant Versus Inconstant 2018–2023 Notification to the Survey

3.4. Fulfillment of the National Target for the Number of Daily ABHR Uses per Resident

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABHR | Alcohol-Based Hand Rub |

| AHHMS | Automatic Hand Hygiene Monitoring System |

| HAI | Healthcare-Associated Infection |

| HdF | Hauts-de-France |

| HH | Hand Hygiene |

| HHC | Hand Hygiene Compliance |

| HHO | Hand Hygiene Opportunity |

| ICL | Infection Control Link |

| IPC | Infection Control and Prevention |

| NH | Nursing Home |

References

- Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (INSEE)—Bilan Démographique. 2022. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/6687000?sommaire=6686521 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Score Santé—STATISS: Statistiques et Indicateurs de la Santé et du Social. Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.scoresante.org%2FuploadedFiles%2FSCORE-Sante%2FStatiss%2FSTATISS_2023_VF.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Henriques, H.R.; Sousa, D.; Faria, J.; Pinto, J.; Costa, A.; Henriques, M.A.; Durão, M.C. Learning from the COVID-19 outbreaks in long-term care facilities: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifolt, M.; Baker, N.; Menefee, R.W.; Kidd, E.; McCormick, L.C. An analysis of ICAR recommendations for long-term care facilities in Alabama. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2024, 52, 974–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jara, B.J. Infection Prevention in the Era of COVID-19: 2021 Basic Procedure Review. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2021, 49, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, J.M.; Pittet, D. HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings. Recommendations of the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee and the HIPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2002, 30, S1–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowicz, J.B.; Landon, E.; Sickbert-Bennett, E.E.; Aiello, A.E.; de Kay, K.; Hoffmann, K.K.; Maragakis, L.; Olmsted, R.N.; Polgreen, P.M.; Trexler, P.A.; et al. SHEA/IDSA/APIC practice recommendation: Strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections through hand hygiene: 2022 Update. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Lee, G.A.; Lee, S.H.; Park, Y.H. A systematic review on the causes of the transmission and control measures of outbreaks in long-term care facilities: Back to basics of infection control. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, J.M. Current issues in hand hygiene. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2023, 51, A35–A43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenen, A.; de Greeff, S.; Voss, A.; Liefers, J.; Hulscher, M.; Huis, A. Hand hygiene compliance and its drivers in long-term care facilities; observations and a survey. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2022, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, A.M.; Hansen, M.B.; Kristensen, B.; Ellermann-Eriksen, S. Hand hygiene compliance in nursing home wards: The effects of feedback with lights on alcohol-based hand rub dispensers. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2024, 52, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveillard, M.; Pradelle, M.T.; Lefrancq, B.; Guilloteau, V.; Rabjeau, A.; Kempf, M.; Vidalenc, O.; Grosbois, M.; Zilli-Dewaele, M.; Raymond, F.; et al. Measurement of hand hygiene compliance and gloving practices in different settings for the elderly considering the location of hand hygiene opportunities during patient care. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2011, 39, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Løyland, B.; Peveri, A.M.; Hessevaagbakke, E.; Taasen, I.; Lindeflaten, K. Students’ observations of hand hygiene in nursing homes using the five moments of hand hygiene. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teesing, G.R.; Erasmus, V.; Nieboer, D.; Petrignani, M.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Vos, M.C.; Verduijn-Leenman, A.; Schols, J.M.G.A.; Richardus, J.H.; Voeten, H.A.C.M. Increased hand hygiene compliance in nursing homes after a multimodal intervention: A cluster randomized controlled trial (HANDSOME). Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbekken, I.H.; Hermansen, Å.; Utne, I.; Grov, E.K.; Løyland, B. Students’ observations of hand hygiene adherence in 20 nursing home wards, during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.; Schwab, F.; Gastmeier, P.; PROHIBIT Study Group; Pittet, D.; Zingg, W.; Sax, H.; Gastmeier, P.; Hansen, S.; Grundmann, H.; et al. Provision and consumption of alcohol-based hand rubs in European hospitals. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 1047–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubitz, S.; Atkinson, A.; Kaspar, T.; Nydegger, D.; Eichenberger, A.; Sommerstein, R.; Marschall, J. Handrub consumption mirrors hand hygiene compliance. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramia, A.; Petrone, D.; Isonne, C.; Battistelli, F.; Sisi, S.; Boros, S.; Fadda, G.; Vescio, M.F.; Grossi, A.; Barchitta, M.; et al. Italian national surveillance of alcohol-based hand rub consumption in a healthcare setting-A three-year analysis: 2020–2022. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, R.; Morvai, J.; Bellissimo-Rodrigues, F.; Pittet, D. Use of hand hygiene agents as a surrogate marker of compliance in Hungarian long-term care facilities: First nationwide survey. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2015, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Brandmeyer, O.; Blanckaert, K.; Nion-Huang, M.; Simon, L.; Birgand, G.; CPias Network. Consumption of alcohol-based hand rub in French nursing homes: Results from a nationwide survey, 2018–2019. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 118, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de la Santé et des Sports—Qualité et Sécurité des Soins: Tableau de Bord 2008 des Infections Nosocomiales & Publication D’indicateurs de Qualité des Soins. Available online: https://sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/DP_IN_indicateurs_decembre09.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. Stratégie Nationale 2022–2025 de Prévention des Infections et de L’antibiorésistance—Santé Humaine. Available online: https://sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/strategie_nationale_2022-2025_prevention_des_infections_et_de_l_antibioresistance.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Repia PRIMO—Connexion. Available online: https://antibioresistance.fr/login (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Mission Primo. Surveillance des Consommations de Produits Hydro-Alcooliques en EHPAD; Résultats de la Phase Pilote Inter-régionale; Santé Publique France: Saint-Maurice, France, 2020; 50p, Available online: https://www.cpias-ile-de-france.fr/docprocom/doc/primo-surveillance-sha-ehpad-dec2020.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Mission Primo. Surveillance des Consommations de Produits Hydro-Alcooliques en Etablissement d’Hébergement pour Personnes Agées Dépendantes; Résultats nationaux, données 2018–2019; Santé Publique France: Saint-Maurice, France, 2021; 39p, Available online: https://antibioresistance.fr/images/PCI/SURVEILLANCE/419492_spf00003002.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Mission Primo. Surveillance des Consommations de Produits Hydro-Alcooliques en Etablissement d’Hébergement pour Personnes Agées Dépendantes; Résultats nationaux, données 2019–2020; Santé Publique France: Saint-Maurice, France, 2022; 47p, Available online: https://antibioresistance.fr/images/PCI/SURVEILLANCE/501111_spf00003727.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Mission Primo. Surveillance des Consommations de Produits Hydro-Alcooliques en Etablissement d’Hébergement pour Personnes Agées Dépendantes; Résultats de la surveillance nationale, données 2020–2021; Santé Publique France: Saint-Maurice, France, 2022; 23p, Available online: https://antibioresistance.fr/images/PCI/SURVEILLANCE/579578_spf00004257.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Mission Primo. Surveillance des Consommations de Produits Hydro-Alcooliques en Etablissement d’Hébergement pour Personnes Agées Dépendantes; Résultats de la surveillance nationale, données 2021–2022; Santé Publique France: Saint-Maurice, France, 2024; 24p, Available online: https://antibioresistance.fr/images/PCI/SURVEILLANCE/RAPPORT2023_PHA.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Mission Primo. Surveillance des Consommations de Produits Hydro-Alcooliques en Etablissement D’hébergement pour Personnes Agées Dépendantes et en Etablissement du Secteur du Handicap; Résultats de la surveillance nationale, données 2022–2023; Santé Publique France: Saint-Maurice, France, 2025; 29p, Available online: https://antibioresistance.fr/images/PCI/SURVEILLANCE/Rapport_surveillance_conso_PHA_ESMS_2022_2023.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- UniSanté—Panorama des EHPAD 2023. Available online: https://www.conseildependance.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-02-21_panorama-ehpad-2022_PDF.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Moore, L.D.; Robbins, G.; Quinn, J.; Arbogast, J.W. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on hand hygiene performance in hospitals. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2021, 49, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhni, S.; Umscheid, C.A.; Soo, J.; Chu, V.; Bartlett, A.; Landon, E.; Marrs, R. Hand Hygiene Compliance Rate During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 1006–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, V.; Kovacs-Litman, A.; Muller, M.P.; Hota, S.; Powis, J.E.; Ricciuto, D.R.; Mertz, D.; Katz, K.; Castellani, L.; Kiss, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on hospital hand hygiene performance: A multicentre observational study using group electronic monitoring. CMAJ Open 2021, 9, E1175–E1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Malliarou, M.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Kaitelidou, D. Quiet quitting among nurses increases their turnover intention: Evidence from Greece in the post-COVID-19 era. Healthcare 2023, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leep-Lazar, K.; Stimpfel, A.W. Factors associated with working during the COVID-19 pandemic and intent to stay at current nursing position. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2024, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, N.; van der Veer, S.N.; Wilson, P.; Dowding, D. Virtual reality and augmented reality smartphone applications for upskilling care home workers in hand hygiene: A realist multi-site feasibility, usability, acceptability, and efficacy study. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2023, 31, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerschmidt, J.; Manser, T. Nurses’ knowledge, behaviour and compliance concerning hand hygiene in nursing homes: A cross-sectional mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.R.; Santos, B.N.D.; Guimarães, C.S.; Ferreira, E.B.; Margatho, A.S.; Reis, P.E.D.D.; Pittet, D.; Silveira, R.C.C.P. Educational technologies for teaching hand hygiene: Systematic review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0294725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlasco, J.; Vicentini, C.; Emelurumonye, I.N.; D’Alessandro, G.; Quattrocolo, F.; Zotti, C.M. Alcohol-based hand rub consumption and world health organization hand hygiene self-assessment framework: A comparison between the 2 surveillances in a 4-year region-wide experience. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, e658–e665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velardo, F.; Péfau, M.; Nasso, R.; Parneix, P.; Venier, A.G. Using patients’ observations to evaluate healthcare workers’ alcohol-based hand rub with Pulpe’friction audits: A promising approach? GMS. Hyg. Infect. Control. 2023, 18, Doc29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Facility Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | Associative | Other | |

| 2018 | 1.83 [1.29–2.69] *,†,$ | 1.37 [0.90–2.43] * | 1.39 [0.87–1.89] * | 2.09 - |

| 2019 | 1.96 [1.38–2.64] *,†,$ | 1.75 [0.81–3.11] | 1.65 [1.03–2.11] * | 1.40 [1.36–1.60] |

| 2020 | 3.55 [2.57–4.38] * | 4.36 [2.13–4.96] * | 3.33 [2.48–4.23] * | 3.10 [2.07–4.18] |

| 2021 | 3.24 [2.26–3.93] † | 1.90 [1.16–3.85] | 2.83 [1.40–4.27] | 1.18 - |

| 2022 | 2.54 [1.82–3.14] *,$ | 1.97 [1.28–2.73] | 1.35 [1.14–2.26] * | 1.96 [1.82–2.31] |

| 2023 | 2.14 [1.64–2.71] *,† | 2.08 [1.25–3.14] | 1.36 [0.79–1.65] * | 2.19 [1.74–2.80] |

| Year | ICL Nurse | IPC Team | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available | Unavailable | Available | Unavailable | |

| 2018 | 1.80 [1.34–2.58] *,†,$ | 1.27 [0.85–2.24] *,† | 1.94 [1.39–2.72] *,†,$ | 1.30 [0.87–1.98] * |

| 2019 | 1.87 [1.37–2.61] *,†,$ | 1.64 [1.08–2.43] * | 1.95 [1.51–2.78] *,† | 1.50 [0.87–2.12] * |

| 2020 | 3.57 [2.61–4.43] * | 3.48 [2.37–4.18] * | 3.72 [2.54–4.58] * | 2.99 [2.29–3.99] * |

| 2021 | 3.21 [1.90–4.08] † | 2.48 [1.31–3.78] † | 3.15 [2.01–4.03] † | 1.88 [1.18–3.77] |

| 2022 | 2.47 [1.65–3.03] *,$ | 2.11 [1.30–3.08] * | 2.50 [1.71–3.16] *,$ | 1.66 [1.28–2.60] * |

| 2023 | 2.00 [1.57–2.64] *,† | 1.69 [1.23–2.72] * | 2.15 [1.58–2.89] *,† | 1.59 [1.04–1.82] * |

| Year | HdF NHs 1 with Daily ABHR 1 Uses ≥ 4 per Resident | % Total HdF NHs | % Total National NHs 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 7 | 3.7 * | NA 1 |

| 2019 | 9 | 5.1 ** | 4.9 |

| 2020 | 52 | 36.1 | 29.3 |

| 2021 | 22 | 24.7 † | 14.1 † |

| 2022 | 18 | 11.1 ***,‡ | 6.7 ‡ |

| 2023 | 12 | 9.0 $,£ | 3.6 £ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alglave, L.; Caudron, M.; Faure, K.; Moreau, C.; Mullié, C.J. Alcohol-Based Hand Rub Purchase as a Surrogate Marker for Monitoring Hand Hygiene in Nursing Homes: Results from a French Regional Survey over the 2018–2023 Period. Hygiene 2025, 5, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene5030039

Alglave L, Caudron M, Faure K, Moreau C, Mullié CJ. Alcohol-Based Hand Rub Purchase as a Surrogate Marker for Monitoring Hand Hygiene in Nursing Homes: Results from a French Regional Survey over the 2018–2023 Period. Hygiene. 2025; 5(3):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene5030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlglave, Louis, Manon Caudron, Karine Faure, Charlotte Moreau, and Catherine J. Mullié. 2025. "Alcohol-Based Hand Rub Purchase as a Surrogate Marker for Monitoring Hand Hygiene in Nursing Homes: Results from a French Regional Survey over the 2018–2023 Period" Hygiene 5, no. 3: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene5030039

APA StyleAlglave, L., Caudron, M., Faure, K., Moreau, C., & Mullié, C. J. (2025). Alcohol-Based Hand Rub Purchase as a Surrogate Marker for Monitoring Hand Hygiene in Nursing Homes: Results from a French Regional Survey over the 2018–2023 Period. Hygiene, 5(3), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene5030039