Abstract

Hand hygiene is a key measure to prevent healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), yet compliance remains low in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), due to limited resources, insufficient training, and behavioral challenges. Simulation-based education offers a promising approach to enhance technical and non-technical skills in safe learning environments, promoting behavioral change and patient safety. This study aimed to develop and pilot a contextually adapted hand hygiene simulation-based learning scenario for nursing students in SSA. Grounded in the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework and Design-Based Research principles, a multidisciplinary team from European and African higher education institutions (HEIs) co-created this scenario, integrating international and regional hand hygiene guidelines. Two iterative pilot cycles were conducted with expert panels, educators, and students. Data from structured observation and post-simulation questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The results confirm the scenario’s feasibility, relevance, and educational value. The participants rated highly the clarity of learning objectives (M = 5.0, SD = 0.0) and preparatory materials (M = 4.6, SD = 0.548), reporting increased knowledge/skills and confidence and emphasizing the importance of clear roles, structured facilitation, and real-time feedback. These findings suggest that integrating simulation in health curricula could strengthen HAI prevention and control in SSA. Further research is needed to evaluate long-term outcomes and the potential for wider implementation.

1. Introduction

Hand hygiene is vital for safe health care delivery, yet practices at the point of care remain suboptimal worldwide [1]. Average hand hygiene compliance without specific improvement interventions remains at around 40%, but can be as low as 2% in low-income countries and 20% in high-income countries [2,3]. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), this compliance is often below the required standards, mainly due to a lack of structural resources, insufficient knowledge about the transmission of infections, and inadequate training [4].

The World Health Organization proposes that global collaboration and investment in hand hygiene research remain essential to promote safe and effective care worldwide [1]. Consequently, it is indicated that long-term enhancements in hand hygiene can be accomplished by integrating numerous actions into a comprehensive strategy. This strategy encompasses system-level modifications to guarantee the availability of adequate infrastructure to facilitate hand hygiene practices. These efforts are further supported by targeted education and training for health workers [5].

Simulation-based education (SBE) is an effective pedagogical intervention at both basic and advanced levels of education, as it helps reinforce and acquire technical and non-technical skills. This approach is valuable because it takes place in a safe environment, and the post-simulation discussion promotes immediate reflection on practice [4,6,7,8]. Other benefits of SBE are incorporating elements of the professional context and experiences of the future professional reality of the students, detecting mistakes and finding strategies to avoid them, and ensuring that the result of an incomplete or incorrect procedure during simulation does not impact a real healthcare situation. Furthermore, the possibility of reflection upon action enhances the learning process for future professional situations [9]. Thus, simulation-based learning scenarios can increase understanding and compliance with hand hygiene guidelines among healthcare professionals and students, which may help reduce the prevalence of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) [4,6,10].

Structured programs incorporating scenario-based training are acknowledged as effective strategies to promote behavior change and improve compliance with infection prevention measures [1]. Simulation-based learning scenarios provide opportunities for deliberate practice and real-time feedback, enhancing technical performance and decision-making. By designing realistic hand hygiene simulation scenarios, healthcare teams can strengthen their institutional safety culture, reduce variability in practice, and contribute to healthcare infection prevention and control (HAI-PC) [1]. Such programs ensure that critical hand hygiene practices are taught, consistently reinforced, and applied in daily clinical routines [4].

This framework supported academic tutors, lecturers, and professors from three healthcare higher education institutions (HEIs) in Europe and four healthcare HEIs in SSA, who designed and piloted a simulation-based program integrated into a capacity-building project. The present paper explores the design and piloting of a hand hygiene simulation scenario as part of the educational process in SSA.

2. Materials and Methods

This study followed an agile piloting process based on iterative design principles to develop and validate a simulation-based scenario to improve hand hygiene practices among healthcare students. The MRC Framework informed the process for developing and evaluating complex interventions [11] and incorporated principles of Design-Based Research [12] to ensure contextual relevance and usability. The primary objective was to ascertain how this specific intervention engenders changes that may prove beneficial, in addition to elucidating the pivotal enablers and constraints on its implementation across HAI-PC educational settings [11,13].

A multidisciplinary team designed the first draft of the scenario, including infection prevention specialists, simulation educators, and clinical practitioners. African HEI partners took primary responsibility for drafting the scenario, with the cooperation of European HEI partners. A specific template for the scenario was created, directly related to the practices of SSA HEI and the healthcare reality settings, following the guidelines of the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL) [7]. The scenario’s contents were supported by the most recent hand hygiene guidelines from local SSA and World Health Organization orientations and inputs on healthcare and educational practices and needs in this area.

This draft scenario was then subjected to two iterative pilot cycles, each structured to progressively refine the scenario based on real-time user feedback and observational data [11,12,13]. The first cycle was carried out to obtain educators’ perspectives on scenario clarity, realism, and instructional value, using expert panels, a recognized rigorous strategy to validate intervention content, ensure contextual appropriateness, and improve credibility in healthcare research [14,15]. The simulation scenario was presented and discussed in one panel with five educators and professionals with expertise in HAI-PC, clinical nursing practice, simulation-based education, and patient safety.

The feedback and suggestions obtained were used to make targeted adjustments to the scenario, and additional refinements were implemented to address identified gaps or challenges, in the face of the analysis of the experts’ contributions.

The revised scenario was tested during cycle two of the agile piloting with five second-year students and four educators, all in the nursing program. The participants’ performance was observed and documented, and structured debriefing sessions were conducted to capture immediate reactions regarding the scenarios’ clarity, realism, and instructional value.

After this cycle, two questionnaires—one for educators and one for students—were created to be applied via Google Forms after the debriefing phase, to assess the participants’ perspectives about the SBE experience.

The Delphi technique supported the development and validation of the questionnaires. This technique ensured the content reflected a consensual, expert-based understanding of the constructs. The Delphi process, a systematic consultative method involving multiple iterative rounds of expert consultation, contributes to the instrument’s content validity and face validity, thereby enhancing its scientific and contextual relevance [15].

This process resulted in seventeen statements focused on relevance, educational effectiveness, and alignment with best practices in hand hygiene. The level of agreement was asked to be between strongly disagreeing and strongly agreeing on a five-point scale. At the end, an open question invited the participant to write suggestions/recommendations to improve the simulation scenario.

The data obtained with the scale were analyzed with SPSS version 29.0 [16] using descriptive statistics to summarize participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and responses to the questionnaire items. In the case of normally distributed data, the continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations (SDs). Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages [17]. The quotations from the open-ended questions were used as referred to by the participant [18].

2.1. Participants

The participants were selected through the utilization of intentional sampling [19]. According to the MRC Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions, the initial phases such as development, feasibility testing, and pilot evaluations do not require large, representative samples. Instead, these phases require the focused, purposive selection of participants who can inform the intervention design, context, and delivery mechanisms [11,13,20].

The sample size was defined based on the number of relevant actors who could enhance the findings’ contextual validity and practical relevance [11,13,21], providing comprehensive insight into the phenomenon of interest [17,18]. Accordingly, the selection criteria for participants were as follows: individuals engaged in the project who had previously been involved in its global development and had direct experience or contextual knowledge relevant to the intervention and its environment.

The sample comprised seven educators, three healthcare professionals, and five students. The expert panel comprised three educators and two nurses from European institutions. Two educators from an SSA HEI, two from a European HEI, and one healthcare professional from a European healthcare institution, all with expertise in HAI-PC and SBE, drafted the simulation template and integrated the suggestions and comments from the expert panel. A total of five students and four educators participated in the second cycle of the agile piloting.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The present study was conducted in two SSA countries, with the requisite ethical approval from the relevant national committees, as outlined below: The case reference number is CREC/726/2023, and the IORG00001212 reference number is also applicable. Approval was obtained in both countries in November 2023, and the studies were conducted between January 2024 and October 2024.

3. Results

Presenting the results of an agile pilot study is a crucial step in developing and evaluating complex interventions under the MRC framework. As emphasized by the MRC, piloting is not a linear process, but rather an iterative phase designed to test and refine key elements of the intervention, its delivery, and evaluation strategies [11,13]. In this study, the active involvement of participants provided essential feedback on the acceptability, clarity, and feasibility of the intervention. This enabled context-specific adjustments to be made, thereby strengthening the overall design. The perspectives of those involved were instrumental in identifying practical challenges and validating the relevance and usability of the intervention components. This process reinforced the iterative nature of early-phase development.

Consequently, the presentation of the results commences with the characterization of the participants, followed by a descriptive justification of the scenario template designed and feedback on the piloting procedure.

The participants in the first cycle were 30% male and 70% female, between 29 and 56 years old, 80% of whom held a master’s degree and 20% a doctoral degree. In the second cycle, the students were in the second year of their graduate studies. The proportion of female students was 40%, while 60% were male, with ages ranging from 20 to 23 years, and a mean age of 21.25 years (SD = 1.26). With regard to the professional category, the sample comprised teaching staff only. The academic qualifications of the subjects under scrutiny were as follows: 25% of the participants held a bachelor’s degree, 50% held a master’s degree, and 25% held a doctorate. The average length of professional experience was found to be 16.66 years.

The following discussion will focus on the structure and content of the simulation scenario template. Following the INACSL orientations [7], the template includes the following sections: target audience, theoretical background, learning objectives, scenario outline, instructor and participants’ roles, equipment/resources needed, procedure checklist, and notes. These items were integrated into the simulation scenario in accordance with the general standards established, following an analysis of local educational and healthcare needs in the context of INACSL orientations.

The contents are supported by the international and regional guidelines on hand hygiene in healthcare facilities, according to the key elements of standard precautions defined by the World Health Organization [1,22]. Maintaining the principle of adaptation to the local reality in educational and healthcare settings [23,24], the content is targeted for nursing, anesthesiology, and midwifery students, considering the existing resources, namely, access to water points, and focusing on HAI-PC.

The theoretical background was explicit in the supporting document provided to the students one week before the simulation-based experience occurred. The final version of this theoretical background included regional and international guidelines, preferably available online, in English and widespread spoken SSA languages, namely Swahili and French. Visual images of the correct procedure, in video format, were also provided in a link format for the students to prepare themselves for the simulation procedure.

Principles for the learning objectives and the scenario outline focused on the student’s competencies development in a student-centered learning process [25], resulting in the definition of five measurable and student-centered learning objectives. Concerning the scenario outline, initially, the story was “…too long and with too much information… what are the students expected to do…?” [Expert 2]. In the face of this, the story was edited to the essential information: “You are the healthcare professional, responsible for administering an intravenous medication. You must ensure correct hand hygiene throughout the process. Before you do the administration, you need to perform hand hygiene and ensure proper safety conditions”.

The instructor’s and participants’ roles and the equipment/resources needed were significant challenges during this study’s development. As SBE was not a regularly implemented educational strategy in these realities, each involved actor’s role was clearly defined. This section of the simulation scenario template included the description of the instructor’s role and each student’s role, including the specific activities to be performed by the intervening students, the observers, and what they have to focus on observing. All environmental issues, like the water point or the hydroalcoholic solution localization, were also mentioned in this section. The equipment/resources needed were directly connected with this information, having all the detailed equipment required to perform hand hygiene and run the simulation-based learning scenario.

The simulation scenario ended with a Procedure Checklist grouped into technical and non-technical procedures, described in detail in a table format that enabled the easy validation of performed/not performed and permitted adding observations. Students suggested a “Notes” item; so, they had a space to add concepts to study and questions to pose to the educators before the beginning of the simulation.

The second cycle of the agile piloting results corroborate that this simulation-based experience includes content that supports the HAI-PC learning and teaching process. The results reveal that, globally, the scenario fulfilled its designated learning objectives and was deemed suitable for implementation on a broader scale [12,14,20]. This highlights the milestones of its creation.

Students strongly agree that the template provides enough background information to prepare themselves for the simulation procedure (M = 4.60, SD = 0.548). All students and all educators strongly agreed that “Learning Objectives are clear” (M = 5.0, SD = 0.000). Students also stated that the story outline has enough information to understand what they must perform during the simulation (M = 4.20, SD = 0.837). Educators also mentioned a higher level of agreement (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of the students’ and educators’ answers.

The agile piloting of this simulation-based learning scenario demonstrates that students and educators agree that this procedure can improve hand hygiene in SSA education and healthcare. According to the students and educators of our study, participation in this SBE experience improves learning the hand hygiene procedure, contributing to HAI-PC learning (M = 4.6, SD = 0.548; M = 4.5, SD = 0.577, respectively). It also allows the development of technical and non-technical skills, increasing students’ confidence in developing the procedure (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of the students’ and educators’ answers (M and SD).

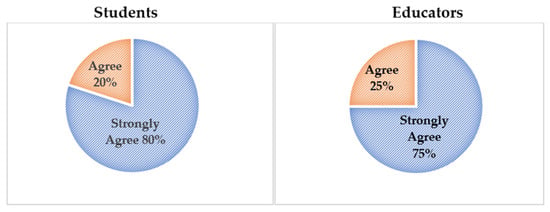

When asked if, based on this experience, they believe a hand hygiene-related simulation-based learning scenario could be a positive addition to the teaching and learning experience in educational programs; 80% of the students and 75% of the educators strongly agreed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of students and educators who agree or strongly agree with this statement.

In the students’ own words, “The simulation is essential for infection prevention and control” (Student C), “It was a great experience, working like this. It gives us time to prepare and do the procedure” (Student D), but “To enhance it [the simulation-based experience], adequate preparation time should be provided for both students and the instructor” (Student A). Educators suggested providing additional refresher training for teachers on script and scenario development techniques.

In conclusion, the findings of this agile piloting study corroborated the relevance, feasibility, and usability of the simulation-based learning scenario that was devised to promote hand hygiene practices in healthcare education. In the initial cycle, the structural and pedagogical elements that necessitated refinement were identified, with particular emphasis on the clarity of the scenario narrative, the delineation of roles, and the specification of requisite resources. These contributions directly informed revisions to the scenario template, improving its alignment with INACSL standards and its adaptability to local educational realities.

The revised version was positively evaluated across all dimensions in the second cycle. It was reported by students that there was a high level of clarity concerning the learning objectives, that the preparatory materials were adequate, and that there was a good understanding of the scenario outline. There was a strong consensus among students and educators that the simulation supported the development of technical and non-technical skills and increased confidence in performing hand hygiene procedures. Furthermore, 80% of students and 75% of educators indicated that this simulation strategy could enhance teaching and learning in their healthcare education context.

4. Discussion

This study describes the development, iterative validation, and primary evaluation of a simulation-based learning scenario designed to enhance hand hygiene practices among nursing, anesthesia, and midwifery students, a topic identified as a priority by the participant HEIs from SSA. In the World Health Organization research agenda on hand hygiene in healthcare 2023–2030, the most significant priority identified was training and educational interventions to improve hand hygiene, focusing on the ability to assess the impact of performance feedback on hand hygiene compliance [1]. The same Organization states that hand hygiene training and educational strategies are essential to improve healthcare professionals’ knowledge and skills at all healthcare system levels [1,22].

The agile piloting process applied in this study ensured the progressive refinement of the scenario’s content, structure, and educational alignment based on experts’, educators’, and students’ feedback and evidence-based guidelines. Integrating input from stakeholders, including students, educators, and HAI-PC experts, was essential to optimize the content and structure of the scenario and align it with the learning objectives. This approach guaranteed that the scenario responded to pedagogical standards and real-world constraints, producing an educationally robust and contextually relevant tool [7,9,22,26].

The scenario was developed in accordance with international and regional recommendations on infection prevention and control [1,2,3,5,22], while also reflecting local constraints such as limited access to water and alcohol-based hand rubs. These challenges are widely documented in healthcare education and practice in SSA [1,22,23,24,27,28]. Similar challenges were reported in studies conducted in Ethiopia and Uganda, which emphasized infrastructure and training limitations as key barriers to compliance among healthcare professional students [29,30].

Furthermore, this study aligns with the best practices for enhancing learner readiness and engagement by incorporating locally adapted theoretical preparation materials, including guidelines and instructional videos in multiple languages in SBE. This is consistent with the most effective practices in SBE, which advocate providing pre-briefing and preparatory materials to ensure optimal learning outcomes [3,4,6,7,8,9,10]. It also supports the findings of a study conducted in Ghana [31].

The scenario structure observed the INACSL standards, incorporating key components such as learning objectives, scenario outline, participant roles, and a performance assessment checklist [7,26]. Emphasis was placed on formulating concise, student-centered objectives that are consistent with the literature showing better learning outcomes when objectives are directly aligned with observable behaviors [25,32], as well as with the INACSL standards [7,26].

Reducing the narrative complexity of the scenario outline enhanced clarity, thereby ensuring that students can readily identify their expected actions during the simulation [7,26] and understand expectations more readily. This is consistent with previous SBE design studies that emphasize narrative realism and brevity for novice learners [32,33,34].

A particular emphasis was placed on delineating the participants’ roles and the resources necessary to facilitate the effective delivery of the scenario. This is particularly important in contexts where simulation-based methods are emerging and, due to uncertainty among facilitators and inadequate facilitation practices, can compromise the effectiveness of the learning experience [3,4,5,9,23,28,32,34]. A similar study in a low-resource context has also shown that clear role descriptions can improve the quality of facilitation and learner psychological safety, particularly when simulation is a novel approach [35].

The scenario promotes structured participation and meaningful engagement by specifying the roles of participants, observers, and facilitators. Well-defined roles provide structure, reduce uncertainty, and ensure that all participants, whether active performers or observers, know precisely what is expected of them during the experience [7,26]. It fosters the development of technical and non-technical skills and reinforces the benefits of role-based engagement, as highlighted in previous simulation research and defended by the INACSL standards [7,26]. This has also been demonstrated by the findings of other studies [36,37,38].

Specifying the roles of students, observers, and instructors allows for targeted engagement, promoting technical and non-technical skill development while maintaining psychological safety [35,36,37,38]. Specifying the instructor’s or debriefer’s role helps focus their facilitation on reinforcing learning objectives, guiding reflective discussions, and providing structured feedback [7,9,25,33,34,35,36,37,38].

This clarity is crucial in low-resource or less-experienced simulation environments, such as those in many SSA educational settings, where learners and faculty may be unfamiliar with SBE methods [3,4,5,9,23,28,32,34]. By integrating explicit role descriptions within the simulation template, academic programs can improve the consistency, relevance, and impact of the learning experience, aligning it with best practices in simulation design and adult education [8,9,36,37,38].

The quantitative findings from the second piloting cycle corroborate the pertinence and adequacy of the results of the first cycle of this agile piloting. They revealed high levels of agreement among students and educators regarding the clarity and relevance of the learning objectives, the adequacy of the preparatory materials, and the appropriateness of the scenario content. Students reported feeling well-prepared to perform the hand hygiene procedure and recognized the scenario’s contribution to their learning about HAI-PC. These findings are consistent with prior studies that underscore the value of SBE in improving technical competence, clinical skills, self-efficacy, and consequently, patient safety outcomes [4,6,8,10,25,36,37]. Similarly, Nget et al. [39] and Sanchis-Sanchez et al. [40] recognized the relevance of the scenarios in enhancing students’ practical skills and knowledge of HAI-PC, while Kaur et al. [41] concluded that students found the scenarios engaging and beneficial for their future clinical practice. Overall, this body of research emphasizes the value of SBE in improving clinical skills and promoting patient safety [4,6,8,10,25,36,37,39,40,41].

Both students and educators highlighted the scenario’s potential to enhance hand hygiene practices and suggested its integration into existing educational curricula. The majority of participants strongly agreed that the experience contributed to their learning and confidence, reinforcing the role of SBE in developing clinical competence [6,8,10]. These findings align with a study demonstrating that incorporating simulation and skills-based instruction into nursing programs can significantly improve students’ preparedness and perceived ability to implement infection prevention protocols in clinical practice [42]. Furthermore, Wiedenmayer et al. [43] reported enhanced healthcare worker compliance with hand hygiene among healthcare workers in Tanzanian health facilities following structured educational interventions based on WHO methodology. This emphasizes the critical role of structured training in environments with limited resources.

Students suggested including a “Notes” section in the checklist, which reflects learner-centered principles [25] and supports continuous reflection and dialogue between learners and educators.

In summary, this agile piloting process validated a contextually adapted, evidence-based, simulation-based learning scenario for hand hygiene education. The findings suggest that this intervention is feasible and acceptable to both students and educators and is perceived as beneficial by these groups. In a reality that often faces challenges such as workforce shortages, limited clinical placement opportunities, and variability in teaching resources, the SBE emerges as a promising strategy to strengthen education in the healthcare area [8,10,36]. Its integration into SSA nursing and allied health curricula may strengthen IPC competencies and reduce healthcare-associated infections.

By addressing context-specific barriers to hand hygiene compliance in SSA, as it incorporated an analysis of the SSA context, including limitations in water availability, placement of alcohol-based hand rubs, and cultural practices influencing hand hygiene behavior, the proposed scenario has a higher potential of a successful implementation of IPC measures as it depends not only on knowledge acquisition but also on the feasibility and acceptability of recommended practices in specific settings [3,25]. In addition, the strong agreement among students and educators regarding the educational value and applicability of the scenario suggests that it can be a key enabler in overcoming these barriers. By allowing learners to practice and reflect on hand hygiene behaviors in simulated, context-relevant environments, this approach fosters technical proficiency and situational awareness—critical factors for improving patient safety outcomes in resource-constrained healthcare systems [8,9,25,36,37,38].

The results further indicate that embedding SBE into SSA nursing and allied health curricula can systematically enhance IPC competencies at this level, strengthening nursing and allied health curricula through simulation. This is particularly important in light of the growing recognition that education and training are central to improving the quality of care and reducing the burden of HAIs across health systems [1,3,5,22,26,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

5. Conclusions

As is known, hand hygiene is a cornerstone of infection prevention, but many regional educational programs lack structured, evidence-based training tools tailored to local resource constraints. The absence of contextually adapted simulation scenarios in curricula contributes to suboptimal compliance and limited student preparedness. This gap underscores the urgent need to integrate pedagogically sound, simulation-based approaches into healthcare education frameworks, ensuring that students acquire theoretical knowledge and the practical competencies required for safe and effective clinical care.

This study reports on the successful development and preliminary validation of a simulation-based learning scenario designed to improve hand hygiene practices among nursing, anesthesia, and midwifery students in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The scenario was developed through an agile, participatory process aligned with international IPC guidelines. It was found to be feasible, contextually relevant, and educationally effective.

The key findings emphasize the importance of clear learning objectives, defined roles, and preparatory materials in fostering student engagement and learning. Based on INACSL standards, the scenario provides a replicable, student-centered model that develops competence and confidence in a safe, realistic environment.

The participants recommended integrating this approach into healthcare education curricula and training faculty, reinforcing its potential for broader implementation. By addressing local barriers and incorporating culturally relevant content, this intervention can support the development of clinical competencies and contribute to infection prevention efforts in SSA.

However, this study has limitations that must be acknowledged. The small number of participants and the absence of a control group limit the generalizability of the findings and constrain the ability to draw causal inferences regarding the intervention’s effectiveness. Since the participants were involved in the development and refinement process, these factors may also introduce selection and response biases.

To overcome these limitations, future research will involve a larger, more diverse sample across multiple institutions. It should include control or comparison groups to strengthen the internal validity of the results. Longitudinal studies assessing knowledge retention, behavioral change, and the impact of integration into institutional curricula would further enhance the evidence base and support the simulation-based intervention’s scalability.

This initiative is a scalable educational strategy that may potentially improve clinical competencies, promote patient safety, and contribute to global efforts to mitigate the burden of healthcare-associated infections.

Author Contributions

The corresponding authors are responsible for ensuring that the descriptions are accurate and agreed upon by all authors and that all authors have reviewed the proofread versions of the manuscript. Conceptualization, P.R., S.N.A., A.C.G., J.R., R.L., J.G., O.Z.A. and B.C.-S.; methodology, A.C.G., E.J.D., C.M., L.N.R. and P.K.; software, A.C.G.; validation, E.C.-K. and P.P.; resources, L.H., P.R., O.Z.A., R.L., S.N.A., E.G.R., P.K., E.J.D., P.N. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R., A.C.G. and S.N.A.; writing—review and editing, A.C.G., S.N.A., P.N., R.L. and M.R.P.; supervision, A.C.G. and M.R.P.; project administration, S.O., R.L., J.R., P.R., M.S., P.G.R. and M.R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded by the European Union (ERASMUS-EDU-2022-CBHE-STRAND-2: 101083108). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committees under the identification CREC/726/2023 and IORG00001212.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author for ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organisation. WHO Research Agenda for Hand Hygiene in Health Care 2023–2030: Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, C.; Delungahawatta, T.; Dunne, C.P. Hand-hygiene-related clinical trials reported between 2014 and 2020: A comprehensive systematic review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 111, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, V.; Daha, T.J.; Brug, H.; Richardus, J.H.; Behrendt, M.D.; Vos, M.C.; van Beeck, E.F. Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartari, E.; Fankhauser, C.; Peters, A.; Sithole, B.L.; Timurkaynak, F.; Masson-Roy, S.; Allegranzi, B.; Pires, D.; Pittet, D. Scenario-based simulation training for the WHO hand hygiene self-assessment framework. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 58. Available online: https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13756-019-0511-9 (accessed on 25 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Guide to the Implementation of the WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/70030 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Kang, M.; Nagaraj, M.B.; Campbell, K.K.; Nazareno, I.A.; Scott, D.J.; Arocha, D.; Trivedi, J.B. The role of simulation-based training in healthcare-associated infection (HAI) prevention. Antimicrob. Steward. Heal. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e20. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9614911/ (accessed on 25 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, P.I.; McDermott, D.S.; Alinier, G.; Charnetski, M.; Ludlow, J.; Horsley, E.; Meakim, C.; Nawathe, P.A. Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice Simulation Design. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 58, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashidi, N.; Pasay, E.; Alrashedi, M.S.; Alqarni, A.S.; Gonzales, F.; Bassuni, E.M.; Pangket, P.; Estadilla, L.; Benjamin, L.S.; Ahmed, K.E. Effects of simulation in improving the self-confidence of student nurses in clinical practice: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat, N.; Camps, A. Simulación Como Metodología Docente En Las Aulas Universitarias. Una Introducción; Institut de Ciències de l’Educació; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; 85p. [Google Scholar]

- Saraswathy, T.; Nalliah, S.; Rosliza, A.M.; Ramasamy, S.; Jalina, K.; Shahar, H.K.; Amin-Nordin, S. Applying interprofessional simulation to improve knowledge, attitude and practice in hospital-acquired infection control among health professionals. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 482. Available online: https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-021-02907-1 (accessed on 27 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Shattuck, J. Design-based research: A decade of progress in education research? Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey-Murto, S.; Varpio, L.; Wood, T.J.; Gonsalves, C.; Ufholz, L.A.; Mascioli, K.; Wang, C.; Foth, T. The use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research: A review. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jünger, S.; Payne, S.A.; Brine, J.; Radbruch, L.; Brearley, S.G. Guidance on conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Streubert, H.; Carpenter, D. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, C.; Dubrowski, A. Piloting Simulations: A Systematic Refinement Strategy. Cureus 2019, 11, e6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. First-Ever WHO Research Agenda on Hand Hygiene in Health Care to Improve Quality and Safety of Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/12-05-2023-first-ever-who-research-agenda-on-hand-hygiene-in-health-care-to-improve-quality-and-safety-of-care (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Ataiyero, Y.; Duson, J.; Graham, M. Barriers to hand hygiene practices among health care workers in sub-Saharan African countries: A narrative review. Am. J. Infect. Control 2019, 47, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irehovbude, J.; Okoye, C.A. Hand hygiene compliance: Bridging the awareness-practice gap in sub-Saharan Africa. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2020, 15, Doc06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.R.; Simões, J.; Reis, A.; Cunha, F.; Caseiro, H.; Patrzała, A.; Bączyk, G.; Jankowiak-Bernaciak, A.; Basa, A.; Valverde, E.; et al. Innovative educational approach in healthcare-associated infection prevention and control. Results of a European study. In Lecture Notes in Bioengineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Bonsu, P.; Acheampong, F.; Nsiah-Asamoah, C. Assessing the impact of a simulation-based learning intervention on hand hygiene knowledge and compliance among nursing students in Ghana. Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. 2021, 13, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Alinier, G.; Hunt, B.; Gordon, R.; Harwood, C. Effectiveness of intermediate-fidelity simulation training technology in undergraduate nursing education. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 54, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motola, I.; Devine, L.A.; Chung, H.S.; Sullivan, J.E.; Issenberg, S.B. Simulation in healthcare education: A best evidence practical guide. AMEE Guide No. 82. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, e1511–e1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.R.; Jense, K.H.; Hviid, A.; Necolau, M.; Matei, I.; Saiz, A.; Lasarte, O.E.; Spieard, M.; van Zaal, H.; Emre, U. How to write good scenarios. Guidelines. Empa(c)t Project. Santarém: Empa(c)t Project. 2019. Available online: https://empact.ipsantarem.pt/atividades/imp_act3.php?reg=-1&lingua=en (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Mwalabu, G.; Msosa, A.; Tjofåt, I.; Urstad, K.H.; Bø, B.; Christina, E. Simulation-Based Education as a Solution to Challenges Encountered with Clinical Teaching in Nursing and Midwifery Education in Malawi: A Qualitative Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 1776533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INACSL Standards Committee; Miller, C.; Deckers, C.; Jones, M.; Wells-Beede, E.; McGee, E. Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice Outcomes and Objectives. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 58, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, T.B.; Abera, B.; Taye, B.; Mulu, W.; Yitayew, G. Hand hygiene compliance among health care workers in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegranzi, B.; Bagheri Nejad, S.; Combescure, C.; Graafmans, W.; Attar, H.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011, 377, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worku, A.D.; Melaku, A. Barriers to hand hygiene practice among healthcare workers in health centres of Kirkos and Akaki Kality sub-cities, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A qualitative study. Infect. Prev. Pract. 2025, 7, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyambadde, R.; Mugerwa, R.; Nakalema, G.; Namuli, L.; Lutalo, T. Evaluation of infection prevention practices among undergraduate nursing students in Uganda. Afr. Health Sci. 2023, 23, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainth, R. Dynamic Plus-Delta: An agile debriefing approach centred around variable participant, faculty and contextual factors. Adv. Simul. 2021, 6, 35. Available online: https://advancesinsimulation.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41077-021-00185-x (accessed on 4 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sahin, G.; Basak, T. Debriefing methods in simulation-based education. J. Educ. Res. Nurs. 2021, 18, 341–346. Available online: https://jag.journalagent.com/jern/pdfs/JERN_18_3_341_346.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- de Góes, F.D.S.N.; Jackman, D. Development of an instructor guide tool: ‘three stages of holistic debriefing’. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, e3229. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32022149/ (accessed on 6 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nget, M.; Neth, B.; Sokchhay, Y.; Vouch, P.; Kry, C.; Soksombat, T.; Gnan, C.; Thida, D.; Koponen, L.; Graveto, J.; et al. Nursing students’ learning experience with healthcare-associated infection prevention and control (HAI-PC) in Asian countries: An exploratory qualitative study. J. Investig. Médica 2024, 5, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Sánchez, E.; Sánchez-Lorente, M.M.; Olmedo-Salas, A.; Zurita-Round, N.V.; García-Molina, P.; Balaguer-López, E.; Blasco-Igual, J.M. Shared learning between health sciences university students. Teaching-learning process of hand hygiene. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’20), Valencia, Spain, 2–5 June 2020; Universitat Politecnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2020; pp. 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Razee, H.; Seale, H. Development and appraisal of a hand hygiene teaching approach for medical students: A qualitative study. J. Infect. Prev. 2016, 17, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikala, A.; Gnanarani, J.; Dhakshinamoorthy, S.; Stachi, N.S. Effectiveness of simulation-based learning module on infection control practices upon competency among nursing students. Asian J. Nurs. Educ. Res. 2025, 15, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenmayer, K.; Msamba, V.S.; Chilunda, F.; Kiologwe, J.C.; Seni, J. Impact of hand hygiene intervention: A comparative study in healthcare facilities in Dodoma Region, Tanzania using WHO methodology. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).