Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions towards Hand Hygiene Practice Amongst Students at a Nursing College in Lesotho

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Period

2.3. Study Site

2.4. Population and Sampling

2.5. Sample Size

2.6. Criteria

2.7. Parameters of Interest

2.8. Data Management and Analysis Plan

2.9. Data Interpretation

3. Results

3.1. The Demographics of the Study Participants

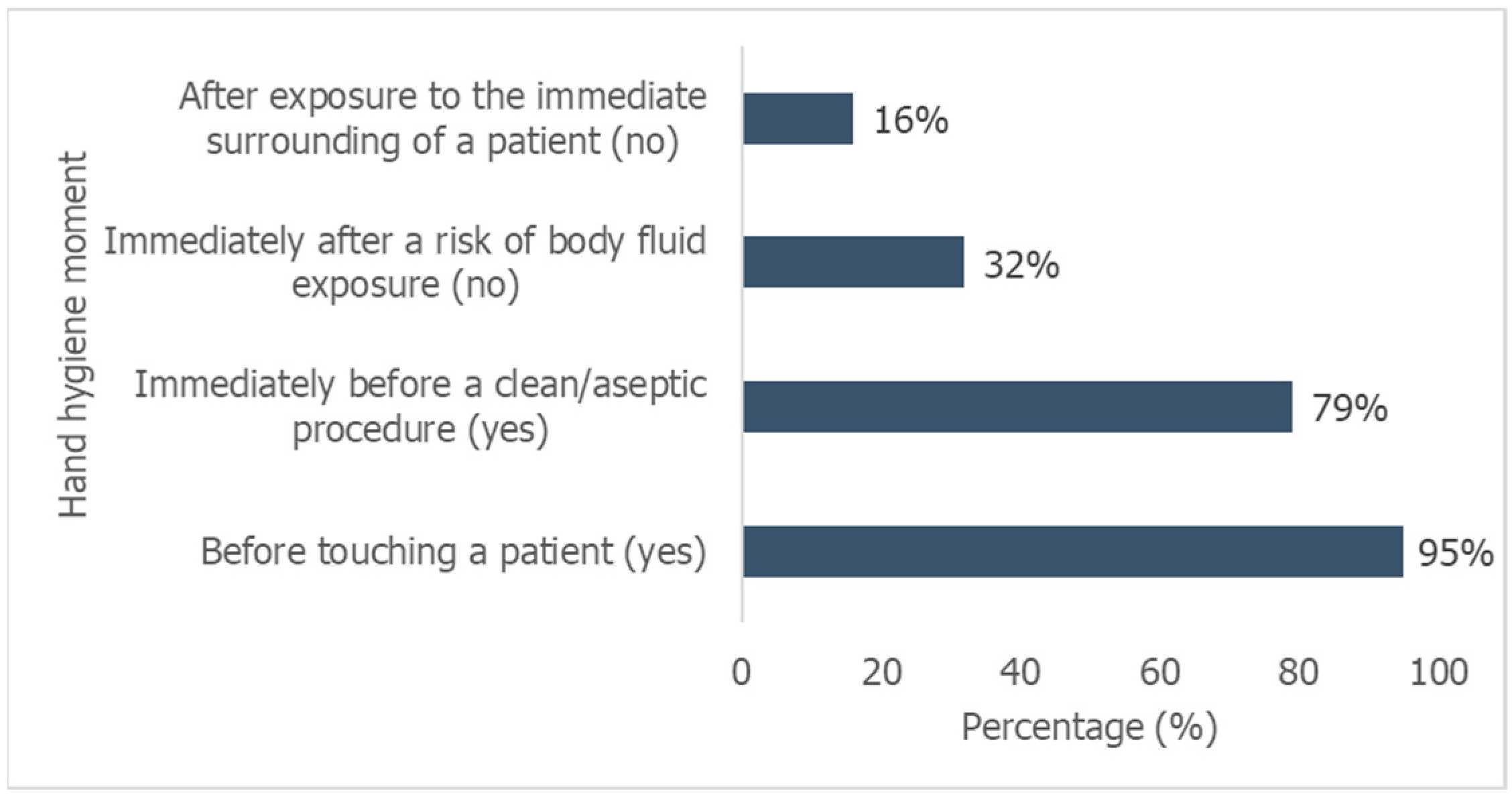

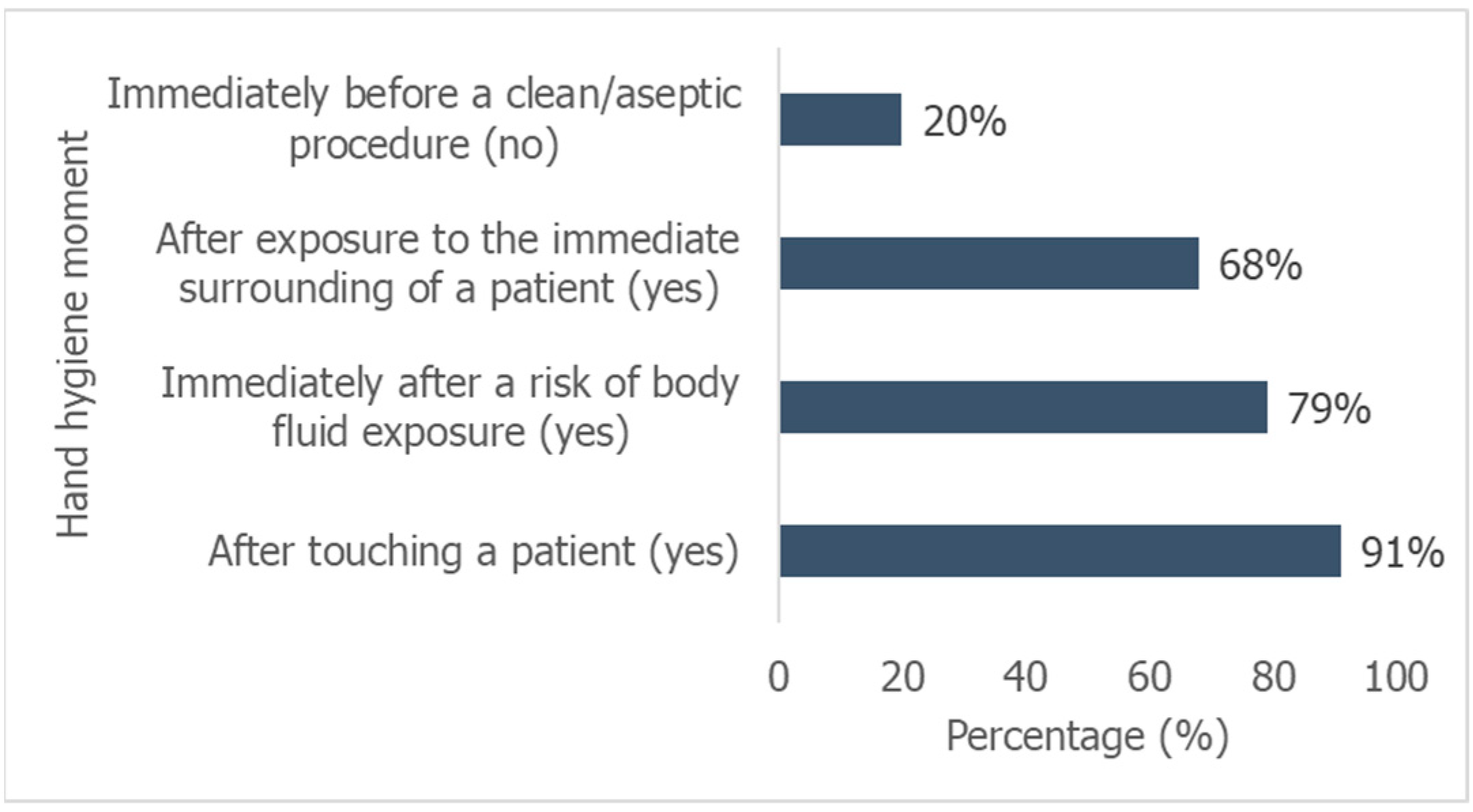

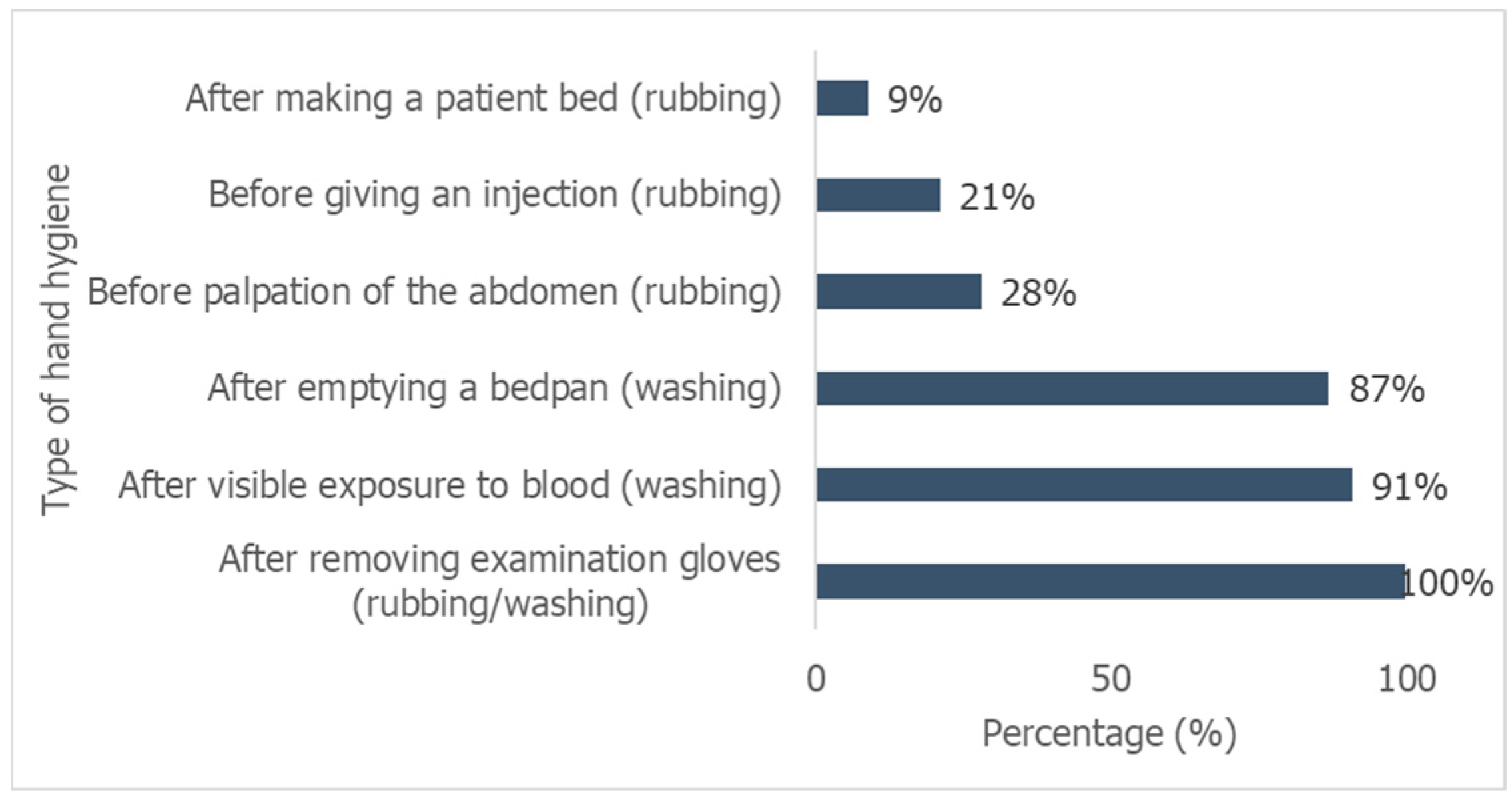

3.2. Level of Knowledge about Hand Hygiene

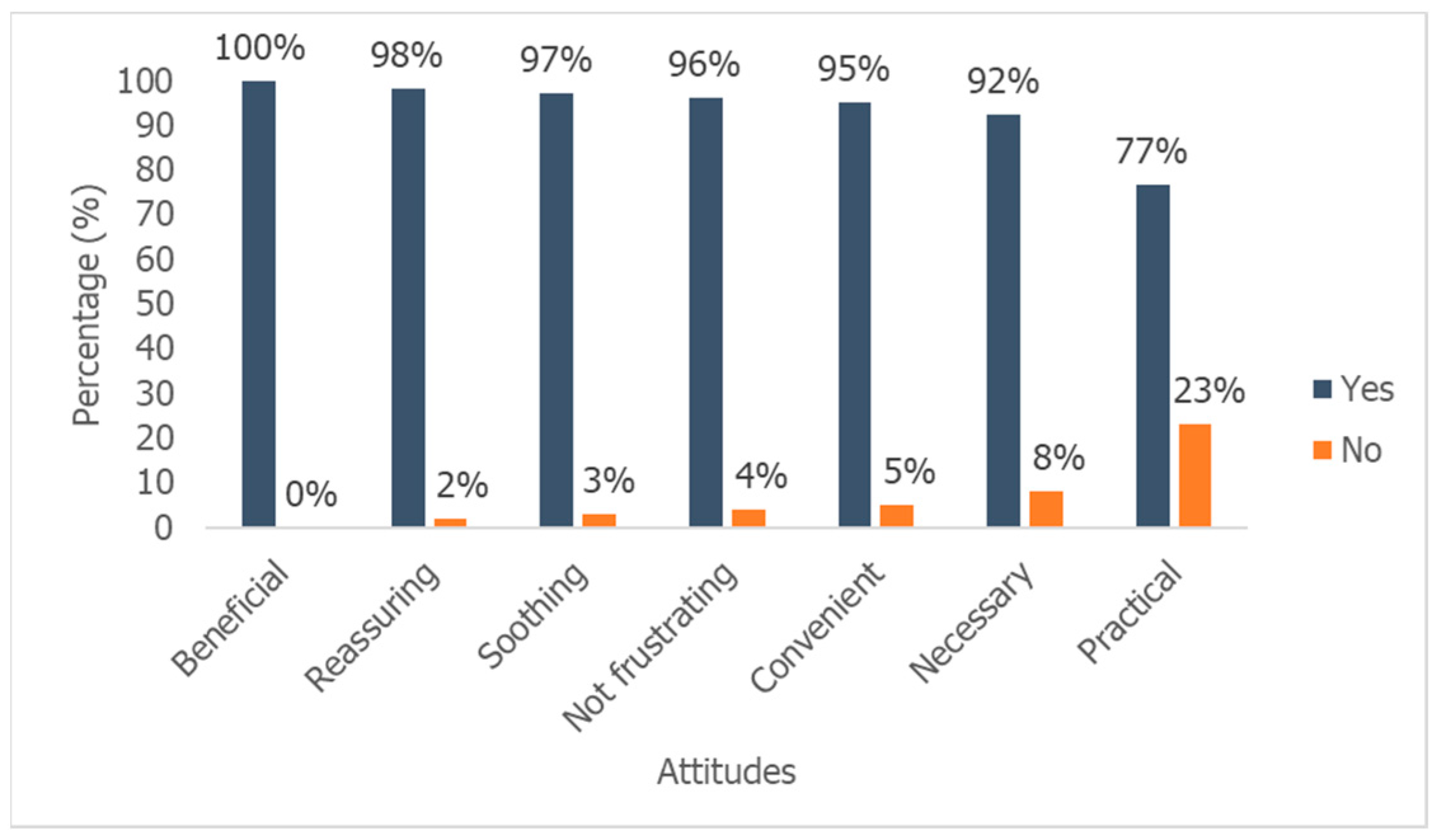

3.3. Attitudes of Student Nurses towards Hand Hygiene

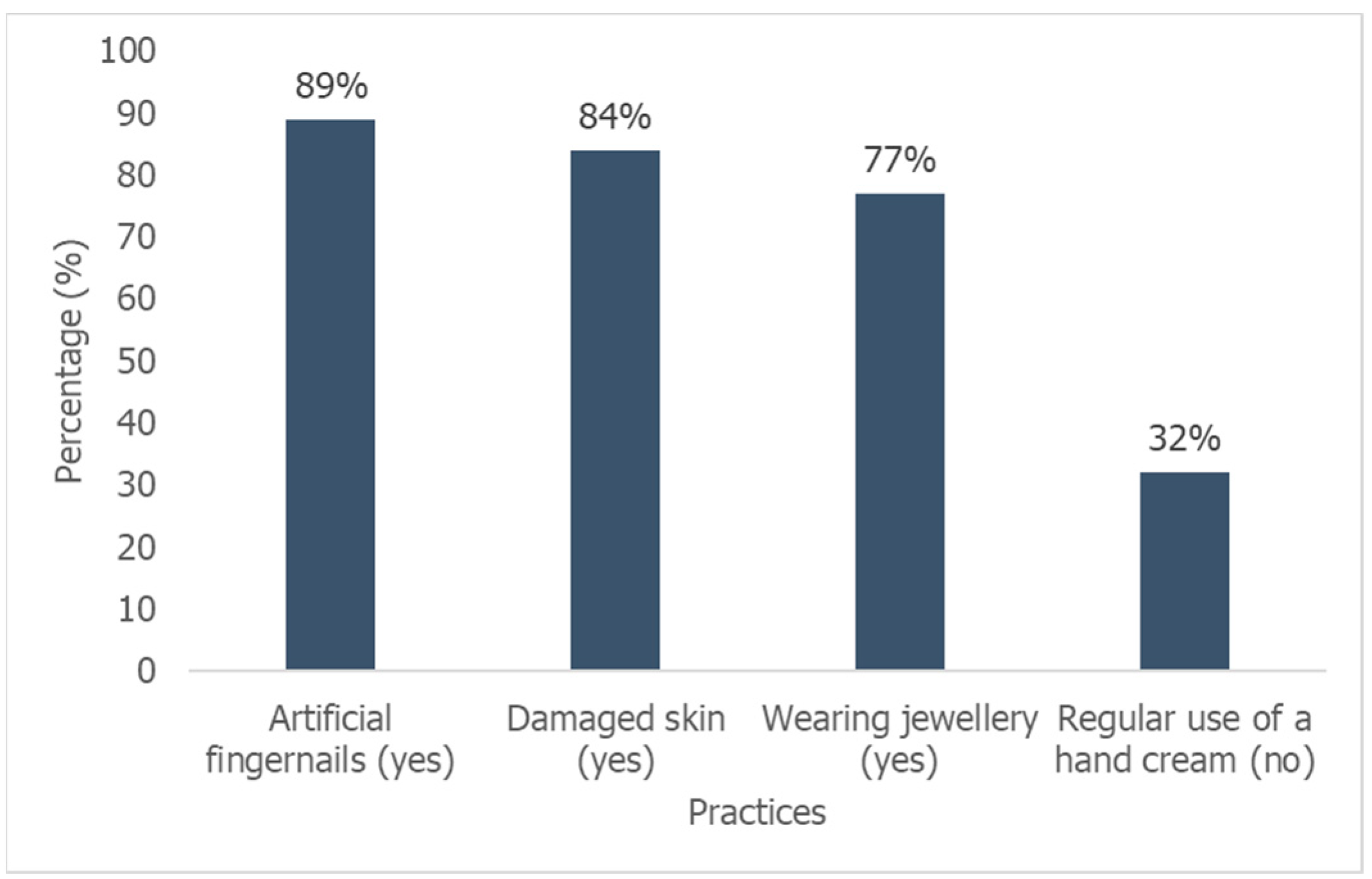

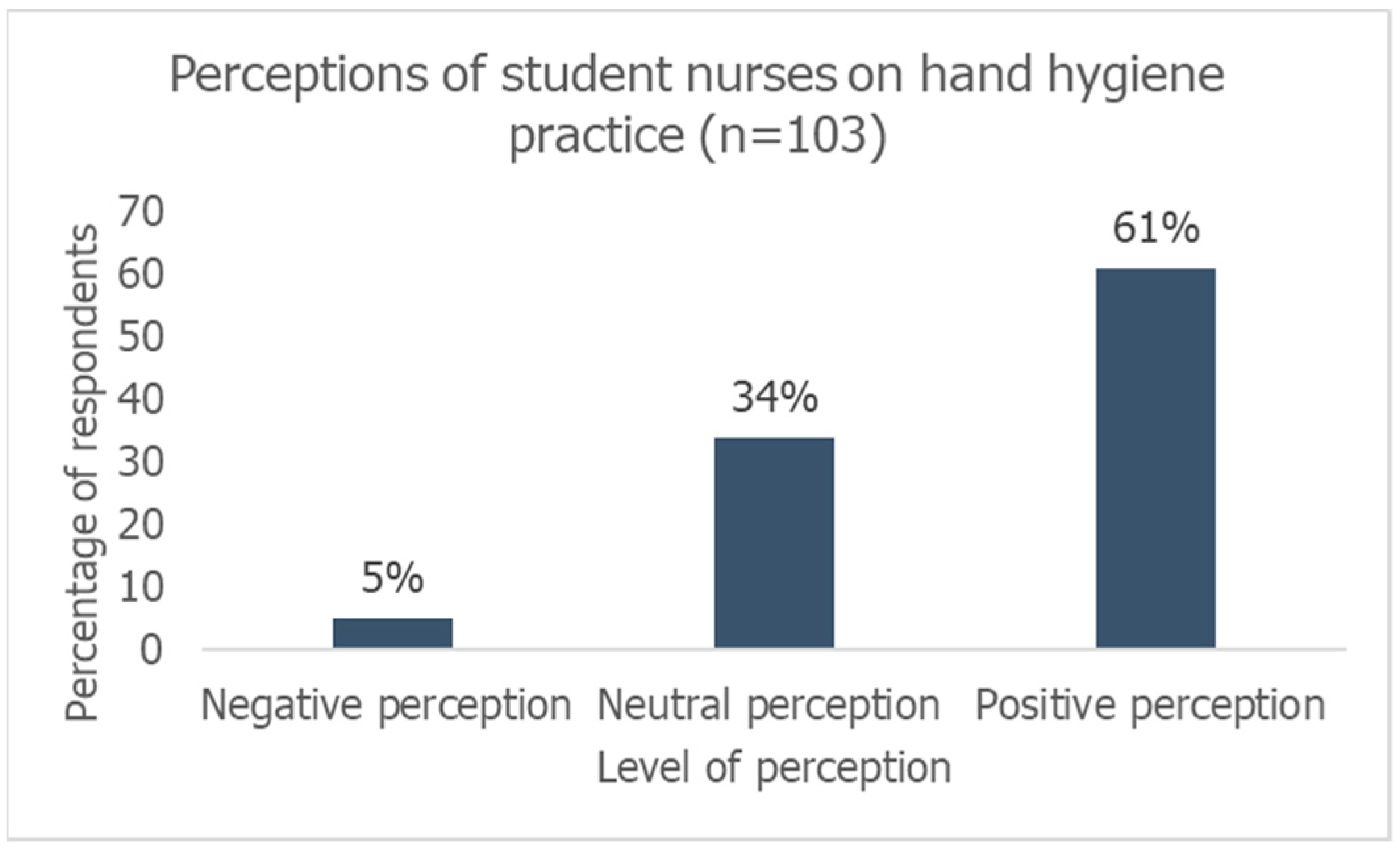

3.4. Perceptions towards Hand Hygiene among Student Nurses

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge

4.2. Attitudes

4.3. Perceptions

5. Recommendations

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. Global Report on the Epidemiology and Burden of Sepsis. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010789 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- World Health Organisation. Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, Second Edition. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Liu, J.Y.; Dickter, J.K. Nosocomial infections: A history of hospital-acquired infections. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. 2020, 30, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apalata, T.; Abaver, D.T.; Fotso, C.B.; Muballe, D.; Vasaikar, S. Postoperative infections: Aetiology, incidence and risk factors among neurosurgical patients in Mthatha, South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2020, 110, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Habboush, Y.; Benham, M.D.; Louie, T.; Noor, A.; Sprague, R.M. New York State Infection Control. 2020. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/NBK/nbk565864 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- World Health Organisation. Hand Hygiene. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/infection-prevention-control/hand-hygiene/guidelines-and-evidence (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Roshan, R.; Feroz, A.S.; Rafique, Z.; Virani, N. Rigorous hand hygiene practices among health care workers reduce hospital-associated infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 2150132720943331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knepper, B.C.; Miller, A.M.; Young, H.L. Impact of an automated hand hygiene monitoring system combined with a performance improvement intervention on hospital-acquired infections. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, J.M.; Laughman, J.A.; Ader, M.H.; Wagner, P.T.; Parker, A.E.; Arbogast, J.W. Impact of an automated hand hygiene monitoring system and additional promotional activities on hand hygiene performance rates and healthcare-associated infections. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatra, S.N. Improving hand hygiene practices to reduce CLABSI rates: Nurses education integral for success. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. Peer-Rev. Off. Publ. Indian Soc. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 23, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S.; Baken, L.; Bor, B. Implementation of a hospital-wide electronic hand hygiene monitoring program reduces healthcare-acquired infections in a level I trauma hospital. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020, 48, S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, A.J.; Gray, S.; Kloppers, J.C.; Navsaria, P.H. Nosocomial infections: A further assault on patients in a high-volume urban trauma centre in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2020, 110, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Five Moments of Hand Hygiene. 2009. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/integrated-health-services-(ihs)/infection-prevention-and-control/your-5-moments-for-hand-hygiene-poster.pdf?sfvrsn=83e2fb0e_16 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Centre for Disease Control. Hand Hygiene in Health Care Setting. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/index.html (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Oh, H.S. Knowledge, perception, and performance of hand hygiene and their correlation among nursing students in Republic of Korea. InHealthcare 2021, 9, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, B.; Gunes, U.; Baran, L.; Ozturk, H.; Sahbudak, G. Examining the hand hygiene beliefs and practices of nursing students and the effectiveness of their handwashing behaviour. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4057–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadpoor, M.; Bahrami Nejad, N.; Ghorbani, F.; Fallah, R. Knowledge, Attitude and Performance of Nursing Students Towards Hand Hygiene in Medical and Surgical Wards of Zanjan Teaching Hospitals in 2019–2020. Prev. Care Nurs. Midwifery J. 2022, 12, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Tripathi, K. Knowledge, attitude and practices of hand hygiene among nurses and nursing students in a tertiary health care center of Central India: A questionnaire-based study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 5154–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tem, C.; Kong, C.; Him, N.; Sann, N.; Chang, S.B.; Choi, J. Hand hygiene of nursing and midwifery students in Cambodia. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019, 66, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz-Hulana, L. Improving hand hygiene compliance amongst second-year nursing students and staff by implementing a standardised aseptic hand wash protocol in hospitals in the Northern Cape Province, South Africa. Wound Heal. South. Afr. 2022, 15, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, G.P. Calculating the sample size in quantitative studies. Sch. J. 2021, 31, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Monitoring Tools. 2009. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/infection-prevention-control/hand-hygiene/monitoring-tools (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Mbroh, L.A. Assessing Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Hand Hygiene among University Students; Minnesota State University: Mankato, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ariyaratne, M.H.; Gunasekara, T.D.; Weerasekara, M.M.; Kottahachchi, J.; Kudavidanage, B.P.; Fernando, S.S. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Hand Hygiene among Final Year Medical and Nursing Students at the University of Sri Jayewardenepura. 2015. Available online: http://dr.lib.sjp.ac.lk/handle/123456789/1854 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Setati, M.E. Hand Hygiene Knowledge, Attitude and Practices among Health Care Workers of Pietersburg Tertiary Hospital. Ph.D. Thesis, ULSpace, Polokwane, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vikke, H.S.; Vittinghus, S.; Betzer, M.; Giebner, M.; Kolmos, H.J.; Smith, K.; Castrén, M.; Lindström, V.; Mäkinen, M.; Harve, H.; et al. Hand hygiene perception and self-reported hand hygiene compliance among emergency medical service providers: A Danish survey. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2019, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaithef, M.; Chandramohan, S.; Hazazi, A.; Elsayed, E.A. Knowledge and perceptions on hand hygiene among nurses in the Asir region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Health Sci. 2020, 9, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mutanekelwa, I.; Molloy, M. Demographics and training factors associated with hand hygiene among nursing students in Solwezi, Zambia: A cross-sectional study. Asian Pac. J. Health Sci. 2019, 6, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, H.S.; Samson, Y.W.; Cherry, N.C.; Ivan, W.Y.; Amy, L.Y. Knowledge, practices, compliance and beliefs of university nursing students’ toward hand hygiene: A cross-sectional survey. GSTF J. Nurs. Health Care (JNHC) 2020, 5. Available online: https://dl6.globalstf.org/ (accessed on 7 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Abuosi, A.A.; Akoriyea, S.K.; Ntow-Kummi, G.; Akanuwe, J.; Abor, P.A.; Daniels, A.A.; Alhassan, R.K. Hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers in Ghana’s health care institutions: An observational study. J. Patient Saf. Risk Manag. 2020, 25, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.C.; Reisinger, H.S.; Schweizer, M.L.; Jones, I.; Chrischilles, E.; Chorazy, M.; Huskins, C.; Herwaldt, L. Hand hygiene compliance at critical points of care. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Disease Control. Clinical Safety: Hand Hygiene for Healthcare Workers. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/clean-hands/hcp/clinical-safety/index.html (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Chauhan, K.; Mistry, Y.; Mullan, S. Analysis of compliance and barriers for hand hygiene practices among health care workers during covid-19 pandemic management in tertiary care hospital of India—An important step for second wave preparedness. Open J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, P.A.; Sladdin, I.; Shaban, R.Z.; Gilbert, J.; Brown, L. Factors influencing hand hygiene practice of nursing students: A descriptive, mixed-methods study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 44, 102746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scale | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Hand hygiene knowledge scale | A scoring system was used, with one point given for each correct response to knowledge and 0 for an incorrect answer. A score of more than 75% was considered good, 50–75% moderate, and less than 50% poor [24]. |

| Hand hygiene attitude scale | Attitudes toward hand hygiene was assessed using a seven-point semantic differential scale using seven different descriptors about participants feeling of practicing hand hygiene, the positive attitude was given 1 score, negative attitude 0 score. Attitude total score 50% and above was considered positive and a score below 50% was negative [25]. |

| Hand hygiene perception scale | 7-point Likert scale variables were collapsed into three categories, the answers 1, 2 and 3 were summed into one “negative” reply, left 4 as neutral, and collapsed 5, 6 and 7 into one “positive” reply [26]. Four questions were considered for the calculation as they mainly determine the perception of student nurses on hand hygiene. The total score ranged from 0 to 4, which was divided into negative, neutral and positive perceptions [27]. |

| Question | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| In your opinion, what is the percentage of hospitalized patients who will develop a healthcare-associated infection (between 0 and 100%) | 0–25% | 17 (17) |

| 26–50% | 18 (17) | |

| 51–75% | 25 (24) | |

| 76–100% | 7 (7) | |

| I don’t know | 36 (35) | |

| In general, what is the impact of a healthcare-associated infection on a patient’s clinical outcome? | Very low | 9 (9) |

| Low | 20 (19) | |

| High | 56 (54) | |

| Very high | 18 (17) | |

| What is the effectiveness of hand hygiene in preventing healthcare-associated infection? | Very low | 1 (1) |

| Low | 12 (12) | |

| High | 42 (41) | |

| Very high | 48 (47) | |

| Among all patient safety issues, how important is hand hygiene at your institution? | Low priority | 2 (2) |

| Moderate priority | 21 (20) | |

| High priority | 28 (27) | |

| Very high priority | 52 (50) |

| Action | Level | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Leaders and senior managers at your institution support and openly promote hand hygiene | Low | 10 (10) |

| Neutral | 14 (14) | |

| High | 79 (77) | |

| The health facility makes alcohol-based hand rub always available at each point of care | Low | 14 (14) |

| Neutral | 16 (16) | |

| High | 73 (71) | |

| Hand hygiene posters are displayed at point of care as reminders | Low | 8 (8) |

| Neutral | 7 (7) | |

| High | 88 (85) | |

| Each healthcare worker receives education on hand hygiene | Low | 5 (5) |

| Neutral | 13 (13) | |

| High | 85 (83) | |

| Clear and simple instructions for hand hygiene are made visible for every healthcare worker | Low | 4 (4) |

| Neutral | 6 (6) | |

| High | 93 (90) | |

| Healthcare workers regularly receive feedback on hand hygiene performance | Low | 34 (33) |

| Neutral | 14 (14) | |

| High | 55 (53) | |

| You always perform hand hygiene as recommended (Being a good example for your colleagues) | Low | 4 (4) |

| Neutral | 8 (8) | |

| High | 91 (88) | |

| Patients are invited to remind healthcare workers to perform hand hygiene | Low | 53 (51) |

| Neutral | 9 (8) | |

| High | 41 (40) |

| Question | Level | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| What importance does the head of your department attach to the fact that you perform optimal hand hygiene | Low | 19 (18) |

| Neutral | 20 (19) | |

| High | 64 (62) | |

| What importance do your colleagues attach to the fact that you perform hand hygiene | Low | 15 (15) |

| Neutral | 15 (15) | |

| High | 73 (71) | |

| What importance do patients attach to the fact that you perform optimal hand hygiene | Low | 36 (35) |

| Neutral | 15 (15) | |

| High | 52 (50) | |

| How do you consider the effort required by you to perform good hand hygiene when caring for patients? | Low | 9 (9) |

| Neutral | 7 (7) | |

| High | 87 (84) |

| Demographic Variables | N (%) | Poor Knowledge n (%) | Good (Good + Moderate) Knowledge n (%) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 91 (88) | 27 (30) | 64 (70) | 0.179 |

| Male | 12 (12) | 1 (8) | 11 (91) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Below 20 | 18 (17) | 7 (39) | 11 (61) | 0.449 |

| 20–24 | 59 (56) | 14 (24) | 45 (76) | |

| Above 24 | 26 (26) | 7 (27) | 19 (73) | |

| Class level | ||||

| 1 | 28 (27) | 12 (43) | 16 (57) | 0.061 |

| 2 | 23 (22) | 7 (30) | 16 (70) | |

| 3 | 19 (18) | 5 (26) | 14 (74) | |

| 4 | 33 (32) | 4 (12) | 29 (88) | |

| Training | ||||

| No | 26 (25) | 12 (46) | 14 (54) | * 0.012 |

| Yes | 77 (75) | 16 (21) | 61 (79) |

| Demographic Variables | N (%) | Poor Attitude n (%) | Good Attitude n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | 91 (88) | 31 (34) | 60 (66) | 1.225 |

| M | 12 (12) | 4 (33) | 8 (67) | ||

| Age | Below 20 | 18 (17) | 8 (44) | 10 (56) | 0.582 |

| 20–24 | 59 (56) | 19 (32) | 40 (68) | ||

| Above 24 | 26 (26) | 8 (31) | 18 (69) | ||

| Class level | 1 | 28 (27) | 11 (39) | 17 (61) | 0.911 |

| 2 | 23 (22) | 7 (30) | 16 (70) | ||

| 3 | 19 (18) | 6 (32) | 13 (68) | ||

| 4 | 33 (32) | 11 (33) | 22 (67) | ||

| Training | No | 26 (25) | 9 (35) | 17 (65) | 0.937 |

| Yes | 77 (75) | 26 (34) | 51 (66) | ||

| Demographic Variables | N (%) | Negative (Negative + Neutral) Perception n (%) | Positive Perception n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | 91 (88) | 36 (40) | 55 (60) | 0.677 |

| M | 12 (12) | 4 (33) | 8 (67) | ||

| Age | Below 20 | 18 (17) | 4 (22) | 14 (78) | 0.133 |

| 20–24 | 59 (56) | 22 (38) | 36 (62) | ||

| Above 24 | 26 (26) | 14 (52) | 13 (48) | ||

| Class level | 1 | 28 (27) | 6 (21) | 22 (79) | 0.072 |

| 2 | 23 (22) | 12 (52) | 11 (48) | ||

| 3 | 29 (18) | 6 (32) | 13 (68) | ||

| 4 | 33 (32) | 16 (48) | 17 (52) | ||

| Training | No | 26 (25) | 8 (31) | 18 (69) | 0.329 |

| Yes | 77 (75) | 32 (42) | 45 (58) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ntaote, M.; Tyeshani, L.; Oladimeji, O. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions towards Hand Hygiene Practice Amongst Students at a Nursing College in Lesotho. Hygiene 2024, 4, 444-457. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene4040033

Ntaote M, Tyeshani L, Oladimeji O. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions towards Hand Hygiene Practice Amongst Students at a Nursing College in Lesotho. Hygiene. 2024; 4(4):444-457. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene4040033

Chicago/Turabian StyleNtaote, Malehlohonolo, Londele Tyeshani, and Olanrewaju Oladimeji. 2024. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions towards Hand Hygiene Practice Amongst Students at a Nursing College in Lesotho" Hygiene 4, no. 4: 444-457. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene4040033

APA StyleNtaote, M., Tyeshani, L., & Oladimeji, O. (2024). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions towards Hand Hygiene Practice Amongst Students at a Nursing College in Lesotho. Hygiene, 4(4), 444-457. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene4040033