Suitability of Methods to Determine Resistance to Biocidal Active Substances and Disinfectants—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Background

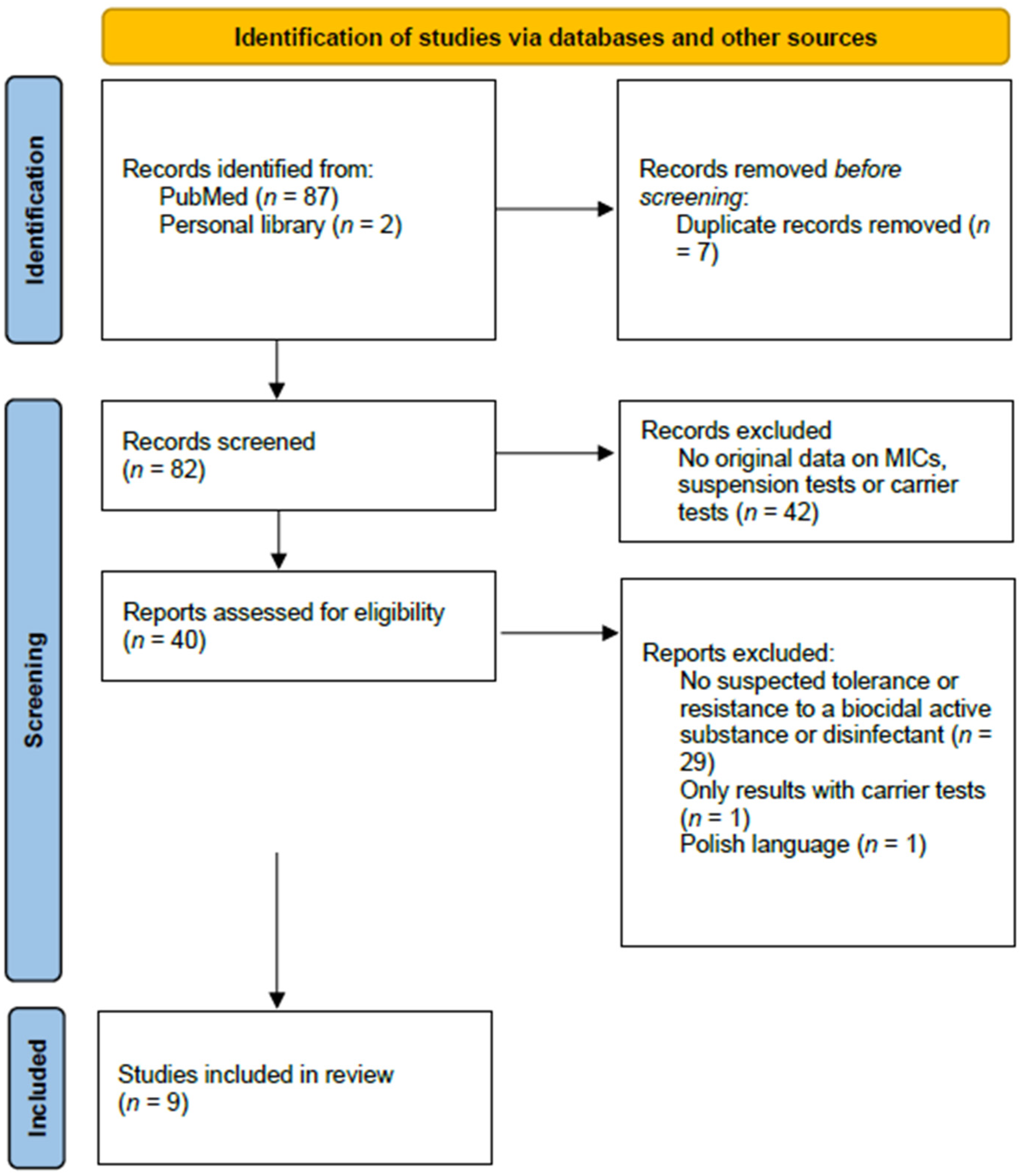

2. Method

3. Results

3.1. Can Elevated MIC Values Predict an Impaired Efficacy in Suspension Tests?

3.2. Can an Impaired Efficacy in Suspension Tests Predict an Impaired Efficacy under Practical Conditions?

3.2.1. Bacteria

3.2.2. Mycobacteria

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EUCAST Methods for the determination of susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial agents. Terminology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 1998, 4, 291–296. [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N.Q.; Helaine, S.; Lewis, K.; Ackermann, M.; Aldridge, B.; Andersson, D.I.; Brynildsen, M.P.; Bumann, D.; Camilli, A.; Collins, J.J.; et al. Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauner, A.; Fridman, O.; Gefen, O.; Balaban, N.Q. Distinguishing between resistance, tolerance and persistence to antibiotic treatment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, I.; Oggioni, M.R.; Knight, D.; Curiao, T.; Coque, T.; Kalkanci, A.; Martinez, J.L. Evaluation of epidemiological cut-off values indicates that biocide resistant subpopulations are uncommon in natural isolates of clinically-relevant microorganisms. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EN 14885; 2019 Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics. Application of European Standards for Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics. CEN-Comité Européen de Normalisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Stickler, D.J.; Thomas, B. Sensitivity of Providence to antiseptics and disinfectants. J. Clin. Pathol. 1976, 29, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.; Baldwin, A.; Dowson, C.G.; Mahenthiralingam, E. Biocide susceptibility of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 63, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura-Sato, K.; Wachino, J.; Kondo, T.; Ito, H.; Arakawa, Y. Correlation between reduced susceptibility to disinfectants and multidrug resistance among clinical isolates of Acinetobacter species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 1975–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciusa, M.L.; Furi, L.; Knight, D.; Decorosi, F.; Fondi, M.; Raggi, C.; Coelho, J.R.; Aragones, L.; Moce, L.; Visa, P.; et al. A novel resistance mechanism to triclosan that suggests horizontal gene transfer and demonstrates a potential selective pressure for reduced biocide susceptibility in clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 40, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Russell, A.D.; Maillard, J.Y. Antimicrobial activity of chlorhexidine diacetate and benzalkonium chloride against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its response to biocide residues. J. Appl. Microbiol 2005, 98, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunke, M.S.; Konrat, K.; Schaudinn, C.; Piening, B.; Pfeifer, Y.; Becker, L.; Schwebke, I.; Arvand, M. Tolerance of biofilm of a carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae involved in a duodenoscopy-associated outbreak to the disinfectant used in reprocessing. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.A.; Babb, J.R.; Bradley, C.R.; Fraise, A.P. Glutaraldehyde-resistant Mycobacterium chelonae from endoscope washer disinfectors. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1997, 82, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Burgess, W.; Margolis, A.; Gibbs, S.; Duarte, R.S.; Jackson, M. Disinfectant Susceptibility Profiling of Glutaraldehyde-Resistant Nontuberculous Mycobacteria. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2017, 38, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.; Sun, H.Y.; Tsai, Y.T.; Wu, U.I.; Chuang, Y.C.; Wang, J.T.; Sheng, W.H.; Hsueh, P.R.; Chen, Y.C.; Chang, S.C. In Vitro Evaluation of Povidone-Iodine and Chlorhexidine against Outbreak and Nonoutbreak Strains of Mycobacterium abscessus Using Standard Quantitative Suspension and Carrier Testing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feßler, A.T.; Schug, A.R.; Geber, F.; Scholtzek, A.D.; Merle, R.; Brombach, J.; Hensel, V.; Meurer, M.; Michael, G.B.; Reinhardt, M.; et al. Development and evaluation of a broth macrodilution method to determine the biocide susceptibility of bacteria. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 223, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovgaard, S.; Nielsen, L.N.; Larsen, M.H.; Skov, R.L.; Ingmer, H.; Westh, H. Staphylococcus epidermidis isolated in 1965 are more susceptible to triclosan than current isolates. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidot, S.J.; Gao, W.; Buultjens, A.H.; Monk, I.R.; Guerillot, R.; Carter, G.P.; Lee, J.Y.H.; Lam, M.M.C.; Grayson, M.L.; Ballard, S.A.; et al. Increasing tolerance of hospital Enterococcus faecium to handwash alcohols. Sci. Transl Med. 2018, 10, aar6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebel, J.; Gemein, S.; Kampf, G.; Pidot, S.J.; Buetti, N.; Exner, M. 60% and 70% isopropanol are effective against “isopropanol-tolerant” E. faecium. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 103, e88–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.D. Biocide use and antibiotic resistance: The relevance of laboratory findings to clinical and environmental situations. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, J.-Y. Resistance of Bacteria to Biocides. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, ARBA-0006-2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffet-Bataillon, S.; Tattevin, P.; Bonnaure-Mallet, M.; Jolivet-Gougeon, A. Emergence of resistance to antibacterial agents: The role of quaternary ammonium compounds--a critical review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 39, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G.; Degenhardt, S.; Lackner, S.; Jesse, K.; von Baum, H.; Ostermeyer, C. Poorly processed reusable surface disinfection tissue dispensers may be a source of infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampf, G.; Degenhardt, S.; Lackner, S.; Ostermeyer, C. Effective processing or reusable dispensers for surface disinfection tissues - the devil is in the details. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2014, 9, DOC09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brooks, S.E.; Walczak, M.A.; Hameed, R.; Coonan, P. Chlorhexidine resistance in antibiotic-resistant bacteria isolated from the surfaces of dispensers of soap containing chlorhexidine. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2002, 23, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrie, T.J.; Costerton, J.W. Proplonged survival of Serratia marcescens in chlorhexidine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1981, 42, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.B.I.; Rodriguez-Rojas, A.; Rolff, J.; Schreiber, F. Biocides used as material preservatives modify rates of de novo mutation and horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 437, 129280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutkina, J.; Marathe, N.P.; Flach, C.F.; Larsson, D.G.J. Antibiotics and common antibacterial biocides stimulate horizontal transfer of resistance at low concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 616–617, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.D. Bacterial resistance to disinfectants: Present knowledge and future problems. J. Hosp. Infect. 1999, 43, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Biocidal Active Substance | Strain | MIC (mg/L) | Mean Log10 Reduction | Exposure Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Providencia spp. | 0.01% CHG * | Four strains (suspected tolerance to CHG) | ≥400 ** | 0.5–1.1 | 10 min | [6] |

| Two control strains (“susceptible to CHG”) | No data | 4.8–5.1 | 10 min | [6] | ||

| 0.01% BAC * | Four strains (suspected tolerance to CHG) | ≥400 ** | 0.5–1.2 | 10 min | [6] | |

| Two control strains (“susceptible to CHG”) | No data | 5.7–6.3 | 10 min | [6] | ||

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | 4% CHG * | ATCC 17616 | 10–20 ** | ≥5.0 | 5 min | [7] |

| LMG 18821 | 90–100 ** | ≥5.0 | 5 min | [7] | ||

| LMG 16660 | 90–100 ** | ≥5.0 | 5 min | [7] | ||

| J 2315 | >100 ** | <5.0 | 1 h | [7] | ||

| Novel group K strain 24 | 90–100 ** | ≥5.0 | 5 min | [7] | ||

| Acinetobacter spp. | 0.0032% CHG * | 20 non-repetitive clinical isolates | 10 ** | 5.0 | 5 min | [8] |

| 28 non-repetitive clinical isolates | >50 ** | 5.0 *** | 5 min | [8] | ||

| 0.0032% BAC * | 20 non-repetitive clinical isolates | 10 ** | 5.0 | 5 min | [8] | |

| 28 non-repetitive clinical isolates | >50 ** | 5.0 *** | 5 min | [8] | ||

| 0.0064% alkyldiaminoethylglycine hydrochloride * | 20 non-repetitive clinical isolates | 10–50 ** | 5.0 | 5 min | [8] | |

| 28 non-repetitive clinical isolates | >100 ** | 5.0 *** | 5 min | [8] | ||

| S. aureus | 0.01% triclosan * | ATCC 6538 | 0.12 **** | 0.3 | 5 min | [9] |

| QBR-102278-1177 | 4 **** | 0.2 | 5 min | [9] | ||

| QBR-102278-1219 | 4 **** | 0.3 | 5 min | [9] | ||

| QBR-102278-1619 | 4 **** | 0.4 | 5 min | [9] | ||

| S. aureus | 0.06% triclosan * | ATCC 6538 | 0.12 **** | 5.5 | 5 min | [9] |

| QBR-102278-1177 | 4 **** | 4.0 | 5 min | [9] | ||

| QBR-102278-1219 | 4 **** | 4.0 | 5 min | [9] | ||

| QBR-102278-1619 | 4 **** | 4.7 | 5 min | [9] | ||

| S. aureus | 0.1% triclosan * | ATCC 6538 | 0.12 **** | >5.5 | 5 min | [9] |

| QBR-102278-1177 | 4 **** | 5.5 | 5 min | [9] | ||

| QBR-102278-1219 | 4 **** | 4.0 | 5 min | [9] | ||

| QBR-102278-1619 | 4 **** | 5.5 | 5 min | [9] |

| Species | Biocidal Active Substance | Strain | MIC Value (mg/L) | Suspension Test | Carrier Test | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean log10 reduction | Exposure time | Mean log10 reduction | Exposure time | |||||

| P. aeruginosa | 0.01% chlorhexidine diacetate * | NCIMB 10421 | 8–10 ** | 3.8 | 5 min | 1.5 | 5 min | [10] |

| Strain Pa 6 | 28 ** | 4.0 | 5 min | 2.2 | 5 min | [10] | ||

| Strain Pa 7 | >40 ** | 3.8 | 5 min | 1.4 | 5 min | [10] | ||

| Strain Pa 8 | >50 ** | 4.1 | 5 min | 1.2 | 5 min | [10] | ||

| Strain Pa 9 | 70 ** | 4.2 | 5 min | 2.0 | 5 min | [10] | ||

| Strain Pa 51a | >70 ** | 4.0 | 5 min | 1.5 | 5 min | [10] | ||

| Strain Pa 54a | >70 ** | 3.9 | 5 min | 1.8 | 5 min | [10] | ||

| Species | Biocidal Active Substance | Strain | Mean Log10 Reduction | Exposure Time | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspension test | Carrier test | |||||

| K. pneumoniae | 0.003% peracetic acid * | Outbreak strain (suspected tolerance to peracetic acid) | ≥5.0 | No data | 10 min | [11] |

| ≤0.0005% peracetic acid * | ATCC 13883 | ≥5.0 | No data | 10 min | [11] | |

| 0.15% peracetic acid * | Outbreak strain (suspected tolerance to peracetic acid) | No data | ≥5.0 | 10 min | [11] | |

| 0.01% peracetic acid * | ATCC 13883 | No data | ≥5.0 | 10 min | [11] | |

| 5% hydrogen peroxide * | Outbreak strain (suspected tolerance to peracetic acid) | ≥5.0 | No data | 10 min | [11] | |

| ATCC 13883 | ≥5.0 | No data | 10 min | [11] | ||

| 0.04% glutaraldehyde * | Outbreak strain (suspected tolerance to peracetic acid) | ≥5.0 | No data | 10 min | [11] | |

| ATCC 13883 | ≥5.0 | No data | 10 min | [11] | ||

| 30% iso-propanol * | Outbreak strain (suspected tolerance to peracetic acid) | ≥5.0 | No data | 10 min | [11] | |

| ATCC 13883 | ≥5.0 | No data | 10 min | [11] | ||

| Species | Biocidal Active Substance | Strain | Suspension Test | Carrier Test | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean log10 reduction | Exposure time | Mean log10 reduction | Exposure time | ||||

| M. chelonae | 2% glutaraldehyde * | NCTC 946 | >5.6 | 1 min | >5.3 | 1 min | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 2% glutaraldehyde * | Isolate from washer disinfector A (previous use of GDA) | 0.6–1.1 | 1 h | 0.0–0.2 | 1 h | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 2% glutaraldehyde * | Isolate from washer disinfector B (previous use of GDA) | 0.0–0.3 | 1 h | 0.0–0.2 | 1 h | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 1% active chlorine * | NCTC 946 | >5.1 | 1 min | >5.1 | 1 min | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 1% active chlorine * | Isolate from washer disinfector A (previous use of GDA) | >5.8 | 1 min | >5.0 | 1 min | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 1% active chlorine * | Isolate from washer disinfector B (previous use of GDA) | >5.2 | 1 min | >5.0 | 1 min | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 0.35% peracetic acid * | NCTC 946 | >5.5 | 4 min | >5.2 | 4 min | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 0.35% peracetic acid * | Isolate from washer disinfector A (previous use of GDA) | >5.1 | 1 min | >5.1 | 1 min | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 0.35% peracetic acid * | Isolate from washer disinfector B (previous use of GDA) | >6.1 | 1 min | >5.0 | 1 min | [12] |

| M. chelonae | 1.5% Glutaraldehyde* | ATCC 35,752 (“GDA susceptible”) | >5.0 | 30 min | >5.0 | 45 min | [13] |

| M. chelonae | 1.5% Glutaraldehyde* | Strain 9917 (“GDA resistant”) | 0.0 | 30 min | 2.3 | 45 min | [13] |

| M. chelonae | 1.5% Glutaraldehyde* | Strain Harefield (“GDA resistant”) | 0.1 | 30 min | 3.6 | 45 min | [13] |

| M. chelonae | 1.5% Glutaraldehyde* | Strain Epping (“GDA resistant”) | 0.0 | 30 min | 1.7 | 45 min | [13] |

| M. abscessus subsp. massiliense | 1.8% Glutaraldehyde * | CIP 108,297 (“GDA susceptible”) | >5.0 | 30 min | >5.0 | 20 min | [13] |

| M. chelonae | 1.8% Glutaraldehyde * | ATCC 35,752 (“GDA susceptible”) | >5.0 | 30 min | >5.0 | 20 min | [13] |

| M. chelonae | 1.8% Glutaraldehyde * | Strain 9917 (“GDA resistant”) | 0.9 | 30 min | 2.3 | 20 min | [13] |

| M. chelonae | 1.8% Glutaraldehyde * | Strain Harefield (“GDA resistant”) | 0.4 | 30 min | 4.4 | 20 min | [13] |

| M. chelonae | 1.8% Glutaraldehyde * | Strain Epping (“GDA resistant”) | 1.0 | 30 min | 1.5 | 20 min | [13] |

| M. abscessus subsp. abscessus | 70% alcohol and 10% povidone iodine * | ATCC 19977 | 3.0 ** | 90 s | 4.6 *** 2.0 **** | 2 min 2 min | [14] |

| 75% alcohol and 2% CHG * | ATCC 19977 | 0.0 ** | 90 s | 3.8 *** 2.3 **** | 2 min 2 min | [14] | |

| M. abscessus subsp. bolletii | 70% alcohol and 10% povidone iodine * | BCRC 16915 | 5.4 ** | 90 s | 5.5 *** 3.0 **** | 2 min 2 min | [14] |

| 75% alcohol and 2% CHG * | BCRC 16915 | 0.0 ** | 90 s | 5.3 *** 2.6 **** | 2 min 2 min | [14] | |

| M. abscessus subsp. massiliense | 70% alcohol and 10% povidone iodine * | TPE 101 (outbreak strain) | 4.1 ** | 90 s | 1.2 *** 0.9 **** | 2 min 2 min | [14] |

| 75% alcohol and 2% CHG * | TPE 101 (outbreak strain) | 0.0 ** | 90 s | 0.9 *** 0.4 **** | 2 min 2 min | [14] | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kampf, G. Suitability of Methods to Determine Resistance to Biocidal Active Substances and Disinfectants—A Systematic Review. Hygiene 2022, 2, 109-119. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2030009

Kampf G. Suitability of Methods to Determine Resistance to Biocidal Active Substances and Disinfectants—A Systematic Review. Hygiene. 2022; 2(3):109-119. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2030009

Chicago/Turabian StyleKampf, Günter. 2022. "Suitability of Methods to Determine Resistance to Biocidal Active Substances and Disinfectants—A Systematic Review" Hygiene 2, no. 3: 109-119. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2030009

APA StyleKampf, G. (2022). Suitability of Methods to Determine Resistance to Biocidal Active Substances and Disinfectants—A Systematic Review. Hygiene, 2(3), 109-119. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene2030009