1. Introduction

The concept of imperial collapse was formerly understood in archaeology to signify a sudden and catastrophic collapse of entire civilisations (

Tainter, 1988;

Yoffee & Cowgill, 1988;

Schrader & Buzon, 2017). Sudden urban abandonment, environmental degradation, economic collapse, catastrophic destruction and violent wars were often associated with this perspective (see, e.g.,

Erdkamp et al., 2021). Since the 2000s, however, a new line of research has emerged that focuses on the continuation of ways of life after the fall of empires (

Schwartz & Nichols, 2006;

McAnany & Yoffee, 2010;

Faulseit, 2015;

Mourad, 2023;

Cline, 2024;

Winter, 2024; see also

Schrader & Buzon, 2017, p. 20 for Sudan).

This is particularly noticeable in Egyptian–Nubian archaeology in the period following the collapse of the New Kingdom. The collapse of the Late Bronze Age in Egypt occurred during the 20th Dynasty, specifically the Late Ramesside period around 1070 BCE (see (

Franzmeier, 2022) for an updated perspective on the end of the New Kingdom). Until the 2000s, the period between 1070 and 850 BCE in Nubia, northern Sudan, was imagined as a Dark Age in Nubian history (see

Morkot, 1994;

Schrader & Buzon, 2017). The initial postulations concerning the collapse of the imperial Egyptian New Kingdom (see

Trigger, 1976;

Adams, 1977;

Kendall, 1982) suggested that the Egyptian withdrawal from Nubia may have prompted local Nubians to either vacate their territories or revert to a tribal lifestyle (see

Schrader & Buzon, 2017, p. 20), making the post-collapse communities in Nubia archaeologically invisible.

In Egypt, the collapse of the New Kingdom was followed by the Libyan Period/Third Intermediate Period (see, e.g.,

Jansen-Winkeln, 2015). For Nubia, there is a considerable lack of sources, and the period between 1050 and 850 BCE is poorly defined (see

Morkot, 1994). A plethora of labels have been utilised to describe this period: Post-New Kingdom, Pre-Napatan, Early Napatan, Third Intermediate Period and Early Kushite. The term ‘Pre-Napatan’, comprising the time between 1050 and 850 BCE, will be employed in this paper. Various chronologies have been suggested for the Napatan period (see, e.g.,

Török, 1995;

Pope, 2020), which is here defined as ranging in time from c. 850 to 400 BCE.

From the inception of the New Kingdom, an Egyptian colony was established in Nubia (northern Sudan) (see

Smith, 2021, with references). This was primarily administered through the establishment of new temple towns that functioned as administrative, religious and economic centres (

Budka, 2020a, with references). Evidence of complex and dynamic population developments has been identified from the period of the 18th Dynasty (

Smith, 2003). The cultural entanglements between the Egyptian and Nubian populations constituted a pivotal aspect of this era, resulting in profound transformations in identity and the establishment of complex social structures (e.g.,

van Pelt, 2013;

Lemos & Budka, 2021;

Smith, 2021).

Taking a bottom-up approach from the perspective of colonial Nubia, this article addresses the question of whether any sociocultural or socioeconomic changes can be identified from 1200 BCE onwards. The primary focus of this study will be on developments in the hinterland of urban administrative centres—such as Sai Island and Amara West—with the Attab–Ferka region in the Middle Nile serving as the primary case study. This article will examine aspects of transformation and resilience in the Late New Kingdom in Nubia, which are, as will be argued, also highly relevant to the subsequent Pre-Napatan and Napatan eras in Nubia.

The integration of archaeological discoveries, material culture, textual evidence and historical data facilitates the formulation of novel narratives from a Nubian-centric perspective, thereby facilitating an understanding of Nubia as a centralised entity rather than the periphery of Egypt with the formation of secondary states. As posited by

Robertshaw (

2019) and others, a considerable number of states in sub-Saharan Africa do not conform readily to the binary classification of ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ states (the latter being regarded as states that emerged under pressure and following the example of neighbouring, already existing [=‘primary’] states, usually agrarian states). This assertion is also applicable to the Napatan Kingdom and the anteceding phase of the Pre-Napatan period in Sudan (for Sudan, see also (

Cooper, 2020), for the concept of nomadic states). In light of the current body of knowledge, it is in general opportune to relinquish the erstwhile supposition that African states occupied a ‘peripheral’ status, whose fundamental objective was purportedly to provision ‘cores’ with raw materials through inequitable systems of exchange, thereby engendering dependency (

Robertshaw, 2019, with references). Recent studies of Nubia and its relationship with Egypt have repeatedly highlighted the limitations of this outdated scholarly model (see, e.g.,

Smith, 2003,

2013,

2021,

2022;

Edwards, 2004;

Spencer, 2014;

Pope, 2020). Whilst a reassessment of Nubia as having active players and a high degree of independence is now widely accepted for the Kerma period, it will be demonstrated below that such an interpretation is also necessary for the Pre-Napatan and Napatan periods.

Recent archaeological work has provided important new insights into the Pre-Napatan period (e.g.,

Schrader & Buzon, 2017;

Buzon & Smith, 2023). New excavations (e.g.,

Welsby, 2023), bioarchaeological approaches (cf.

Buzon et al., 2024) and ceramic studies (

Rose, 2019;

Heidorn, 2023;

Welsby Sjöström, 2023) have prompted a re-evaluation of the continuity of lifeways in the aftermath of the New Kingdom, with a particular emphasis on the role of local agency in the Middle Nile region. There are data attesting to social and economic changes from 1200 BCE onwards not only in Sudan but also in Egypt (see

Jansen-Winkeln, 2015).

The most significant case studies have been conducted in Tombos (

Buzon & Smith, 2023) and Amara West (

Spencer, 2014;

Gasperini, 2023), in particular in mortuary contexts. Studies of ceramics and material culture more broadly (see

Howley, 2018), as well as the use of bioarchaeological methods, have helped develop a better understanding of the diverse mortuary practices used, particularly when complemented by theoretical advances, such as the integration of cultural entanglement concepts into the archaeology of Nubia (see

Buzon et al., 2016).

2. Materials and Methods

This paper presents new archaeological findings from a rural area in the northern part of the Middle Nile in Sudan, the Attab–Ferka region. Since 2018, fresh archaeological fieldwork has been conducted in this region as part of the Munich University Attab to Ferka Survey (MUAFS) project (see

Budka, 2019,

2020b,

2024b) and has yielded substantial remains from the first millennium BCE. These findings complement recent discussions about complex sociocultural formation processes in Nubia between 1070 and 850 BCE, which are based on work carried out at urban sites such as Tombos and Amara West.

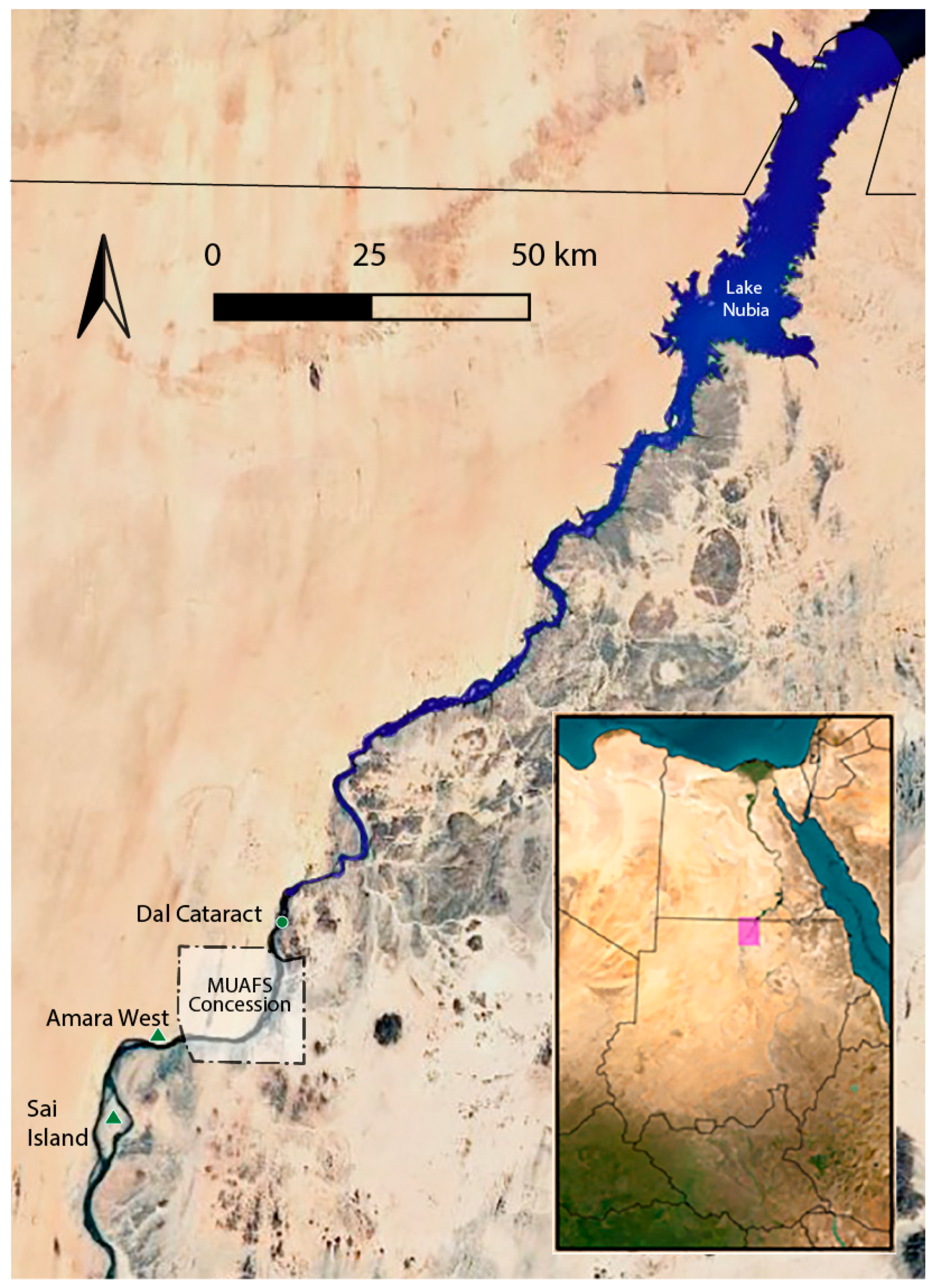

2.1. The Attab to Ferka Region

The following article offers new evidence from the Attab to Ferka region in northern Sudan for the time span between the Late New Kingdom and the Napatan era. The area covered by the MUAFS concession is extensive, encompassing a region of over 337 km

2 south of the Dal cataract (see

Figure 1). This area includes the districts of Attab, Ginis, Kosha, Mograkka and Ferka. Since 2020, the ERC DiverseNile project has been evaluating specific living conditions during the Bronze Age in the MUAFS concession with the aim of reconstructing Contact Space Biographies (for this concept, which combines models of contact spaces, changing landscapes and technologies used by the region’s inhabitants, see (

Budka et al., 2025)).

A substantial portion of the research area encompassed by the MUAFS project was surveyed during the 1970s under the direction of André Vila on behalf of the French section of antiquities in Sudan (Section Française de la Direction des Antiquités du Soudan [SFDAS]) and the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums in Sudan (NCAM) (

Vila, 1975;

Ward, 2024). Many of the sites identified in this survey were relocated and recorded by foot and car surveys over several seasons of the MUAFS project (2018–2025), during which time a number of additional sites were also identified and recorded. The MUAFS survey was supplemented by the utilisation of drone aerial photography. Together, this formed the basis of our GIS database of archaeological sites in the MUAFS concession area, which we use to analyse site distribution, particularly in relation to the local landscape and significant geological changes (see

Budka et al., 2025).

A total of 24 sites spanning the period from the New Kingdom to the Napatan era, 7 of which that were not noted by Vila but that were documented by the MUAFS project, are mapped in

Figure 2. The sites in question are as follows: three New Kingdom and Pre-Napatan sites, six New Kingdom and Napatan sites, two Pre-Napatan sites, four Pre-Napatan/Napatan sites and eight Napatan sites, of which two are questionable. Furthermore, one site (2-T-28 in Ginis East) dates back to the Kerma period. However, it was used as a burial ground during the Napatan period prior to its reuse as a domestic site in Medieval times. It is noteworthy that only 9 of the 24 sites under consideration are tombs or cemeteries.

In terms of dating, it is imperative to acknowledge that the time frame utilised for the sites is contingent on material evidence, encompassing pottery, other artefacts and architectural features. Presently, no data from absolute dating methods, such as radiocarbon dating or optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating, is available.

2.2. Late New Kingdom and Pre-Napatan Sites

Sites with evidence of use during the Late New Kingdom and the Pre-Napatan era include both settlement and mortuary contexts. The mortuary contexts are various types of cemeteries. For example, depsite being looted in antiquity, several tumuli cemeteries in Attab East (e.g., 2-T-48,

Vila, 1977b, pp. 55–56) and Ginis West (2-T-58,

Vila, 1977a, pp. 119–122) can be dated to the Late New Kingdom, the 20th Dynasty and the Pre-Napatan period. Their dating to the Late New Kingdom/Pre-Napatan era is corroborated by ceramics from the destroyed chambers and corrects Vila’s assumption that these burial mounds were ‘Pharaonic’ tombs.

However, it is important to note that by the 1970s, 2-T-58 had already been significantly damaged and looted. It is highly improbable that further information of a more substantial nature than that amassed by Vila can be obtained from these tombs (

Vila, 1977b, pp. 119–122, figs. 53–54). Vila conducted an excavation of one of the tombs, unearthing the remains of four burials, including funerary beds, bodily adornments such as beads and amulets and ceramic vessels. These artefacts appear to date to the late Ramesside period and the Pre-Napatan phase based on well-dated parallels. Similar artefacts have been found in other locations, including Amara West (

Binder, 2014) and Hillat el-Arab (

Vincentelli, 2006) dating to the Late New Kingdom/Pre-Napatan period. Therefore the most likely date for this excavated tumulus and its interments is the Pre-Napatan period.

A different type of cemetery is attested to with Site 2-T-13/GiE 002 in Ginis East. Vila and his team dated this small cemetery, which once had stone superstructures over the grave that had since largely been dismantled, to the New Kingdom. However, the single pit burial excavated in the 1970s, in particular the ceramic evidence, suggests that this date is too early (

Vila, 1977a, pp. 47–48, fig. 16). Part of the site was excavated in 2022 following a magnetometry survey in 2019 (see

Budka et al., 2025, fig. 8). A total of eight trenches and one small extension were investigated, and only two graves of the pit burial type as described by Vila were discovered. However, Feature 2 had an intriguing niche sealed from the main pit with mud-bricks and some datable material (see below). All in all, based on our re-excavation, this cemetery was primarily used in the 10th–8th centuries BCE during the Pre-Napatan and Napatan periods but also has evidence for later burials (likely Medieval). However, no evidence for use during the New Kingdom was identified.

Several domestic sites on the west bank show continuous use from the New Kingdom to the Pre-Napatan period. Habitation site 3-P-15 at Kosha West is of particular interest, as it provides evidence of continuation occupation from the late Ramesside period into the ninth and possibly even the eighth century BC, as indicated by the analysis of surface ceramics (

Budka, 2019, Pl. 5). More precise dating and concise characterisation would require excavation. The site is situated on a mound with a diameter of 55,100 m with a surface characterised by the presence of schist blocks and sherds. In the northeastern part of the site, the remains of mud-bricks are visible. The surface ceramics documented in this study demonstrate an uninterrupted sequence that extends from the late Ramesside period into the ninth and potentially even the eighth century BCE, thus into the Napatan era.

3-P-15 constitutes a component of a cluster that was formed of three settlement sites in the Kosha West district (3-P-15, 3-P-16 and 3-P-17). These sites comprise the remnants of structures situated on three isolated mounds within the dune area, which is characterised by the presence of tamarisks. The distance to the Nile is between 100 and 150 m. This group of habitation sites had already been noted by André Vila in the 1970s, and he attributed all of them to the Egyptian New Kingdom (

Vila, 1976, p. 108).

Site 3-P-17 can be identified by a few mud-bricks and scattered stones on a mound, and the total size of the site remains unclear. Based on the ceramic finds we documented on the surface in 2019, this site can be attributed to the early 18th Dynasty.

The remains of 3-P-16 are located on a circular mound with a diameter of approximately 50 m. In the southeastern sector of the mound, there is a substantial quantity of mud-bricks, suggesting the presence of a fortification in this area during historical periods. The dating of this structure remains unclear without excavation; the surface material suggests a New Kingdom date, possibly Ramesside (Late New Kingdom), but some Medieval sherds were also identified. Overall, there are still a number of open questions regarding the domestic sites in Kosha West.

One site in Ginis West can be used to illustrate the methodological challenges in identifying Vila sites on the ground by means of a foot survey. The location of Site 2-T-67, decribed by Vila as cluster of channels and basins dating to the New Kingdom (see below), remained undetermined during fieldwork conducted in 2019 and 2022. However, remote sensing with orthoprojections based on drone aerial photographs enabled identification in 2024. Utilising this knowledge, the re-identification of the site in the sandy terrain on the ground in 2025 was easily accomplished.

Finally, on the east bank, a gold extraction site at Ginis East with Ramesside, Pre-Napatan and also propable Napatan evidence, 3-P-34, is also of great significance (again erroneously attributed to only the New Kingdom by (

Vila, 1977a, p. 94; see

Budka, 2024a)). This site, which contains numerous artefact concentrations and deposits of crushed quartz on the surface, represents a significant new addition to New Kingdom gold-working activities in the Batn el-Hagar region (see

Klemm & Klemm, 2017;

Budka, 2024a) and their continuation in later times.

2.3. Napatan Sites

It is important to note that no sites within the MUAFS concession area were assigned by Vila to the Napatan period. As will be explained in the following, Vila’s dating needed to be revised in some cases—particularly for some of the sites he identified as New Kingdom—based on our foot survey and the assessment of the surface ceramics.

The eight Napatan sites within the MUAFS concession (

Figure 2) have considerable potential, particularly given they were previously unknown. Three are mortuary sites, the rest are of domestic character. Of particular note are the stone walls and huts, which form three substantial settlement sites on the left bank in the district of Ginis (2-T-53, 2-T-57 and 2-T-69), situated in the ‘Sand Hills along River’ (as indicated on a map of 1886, see

Woodward et al., 2017, pp. 228–229, fig. 1) between tamarisks and acacia trees and still predominantly covered by sand (

Figure 3). The dating of these sites by Vila to the New Kingdom was due to an erroneous interpretation based on the presence of wheel-made ceramics (see below). As will be specified below, the sandy terrain of these sites rendered full mapping of features on the ground a very challenging task. In this instance, the 3D models and orthophotoprojections for remote sensing were of significant importance.

3. Results

The following summarises the results of some of the work achieved so far for the relevant sites dating to the Pre-Napatan and Napatan periods in the Attab to Ferka region, with a particular emphasis on domestic sites.

Prior to the initiation of the MUAFS project, no Napatan settlement sites had been documented in the Attab to Ferka region. In general, Post-New Kingdom settlements in Nubia are difficult to trace. This is primarily due to a paucity of architectural evidence and difficulties in dating both occupation and abandonment phases. Derek Welsby has emphasised that despite the survival of numerous New Kingdom sites, the intricacies, formation and settlement patterns of Napatan settlements in Sudan remain ambiguous (

Welsby, 2019). As will be demonstrated in the following, the new data from the Attab to Ferka region in the Middle Nile can help address these issues and facilitate a novel perspective on cultural and societal transformations at the close of the Egyptian New Kingdom in colonial Nubia.

3.1. Site Distribution

A thorough investigation into the distribution of sites from the Pre-Napatan and Napatan periods, which succeeded the New Kingdom collapse, was undertaken. The analysis of this distribution revealed that all the pertinent sites are located in Attab and Ginis (

Figure 2). This is of particular interest given the extensive evidence of human activity in these districts during the Kerma and New Kingdom periods. This observation suggests a certain degree of continuity.

While on the east bank there are both mortuary and domestic sites, those located on the west bank are predominantly domestic in character. In general, the western bank across all districts from Attab to Ferka has a slightly lower number of archaeological sites than the eastern bank. The ratio between settlement sites and burial sites varies between time periods (

Budka, 2019).

The prevalence of Pre-Napatan and Napatan settlement sites in Attab, Ginis and Kosha seems to be related to the main paleochannel of the region. The environmental conditions of this landscape have undergone significant changes over time. Woodward and his team (

Woodward et al., 2017) have already demonstrated that the New Kingdom was a period of significant environmental change, marked by the drying up of water channels in the region. This assertion was further substantiated recently by Dalton and colleagues (

Dalton et al., 2023; see also

Budka et al., 2025).

3.2. Examples of Settlements

3.2.1. Mud-Brick Buildings

Excavations were undertaken in 2025 at the Late New Kingdom sites 2-T-62/1 and 2-S-50/1 in Attab West. The locations of these two sites are shown on

Figure 4.

In February 2025, a re-excavation was conducted on Site 2-T-62/1, which had previously been exposed and documented by Vila in the 1970s (

Vila, 1977b, pp. 88–89). The edifice is composed of mud-brick, with schist stone fragments present on the surface, filled with windblown sand, (for an orthoprojection of structure 2-T-62/1 overlain with a plan based on (

Vila, 1977b, fig. 48; see

Ward et al., 2025, fig. 11a)). Vila’s dating of the structure placed it within the New Kingdom. The presence of the ancient structure was already discernible from our initial surface clearance had been completed. Re-excavation revealed the northern wall and parts of the eastern and western walls; where only the foundation course and the mud floor have survived. Three marog pits (soil extraction pits) have partially destroyed some of the mud-bricks (see

Figure 5). The material associated with the structure, especially the pottery, allows us to propose a more precise dating to the Late New Kingdom.

Following a comprehensive investigation, the general accuracy of Vila’s published plan of the structure can be confirmed, notwithstanding the three marog pits (which presumably occurred subsequently), resulting in the partial destruction of the building. A mud-brick pavement was evident in the northwestern part of the site. The dimensions of the individual bricks are approximately 40 × 15/20 × 8 cm, as previously noted by Vila; however, different formats were documented on the west wall (42 × 20 × 8 cm; 40 × 23 × 8 cm). Vila’s estimation of the dimensions of the building was approximately 9 × 7 m; however, our measurements indicated a width of 8.80 m instead of 9 m. In the northwestern corner, four layers of mud-bricks were preserved. In this instance, the dimensions of the brick sizes utilised in the foundation layers also exhibit variability, with measurements ranging from 35 × 15 × 8 cm to 39 × 20 × 8/9 cm. Such a variety of brick formats is a bit unusual and not found at the colonial site of Sai where only two brick formats were mostlyused (33 × 15 × 10 cm and 40 × 19 × 9 cm, see

Adenstedt, 2016, p. 23). At Amara West, the usual length of the bricks is 38 cm (see

Spencer, 2017, p. 339). The significance of the variety of brick formats in 2-T-62/1 remains to be elucidated. Different construction phases can be ruled out, as the bricks in question all come from the solid foundation of the building. It is conceivable that foundations, which are, invariably, not subjected to the same detailed examination of standing architecture, such as at Amara West, are more likely to exhibit variation in brick format and are associated with purely practical work processes.

Excavations at Site 2-S-50 in Attab West were conducted by Vila in the 1970s, who dated the site to the New Kingdom period. A re-examination of the site, located on a small hill above the main paleochannel of the region, was undertaken in 2025, and a mud-brick structure, labelled Structure 1, was cleared of windblown sand.

Structure 1, the largest building in Site 2-S-50, is a substantial mud-brick structure with a particularly well-preserved northern wall (with an estimated length of c. 9 m) (

Figure 6a). Only preliminary cleaning has been conducted so far and a thorough excavation of the structure would likely yield more significant results. The structure bears a strong resemblance to Vila’s 2-T-62/1 site (

Figure 6b), and the majority of the ceramics are similarly dated to the Late New Kingdom, although some Pre-Napatan examples are also present.

Both mud-brick buildings revealed a considerable amount of pottery dominated by Egyptian-style wares and only a limited number of Nubian-style handmade wares. This represents a significant decrease in Nubian wares compared to sites in the region dating to the beginning of the colonial period in the early New Kingdom. However, new ‘hybrid’ ceramics enable us to trace local adaptations of material culture (see below).

The pottery found in 2-S-50’s Structure 1 raises some significant questions. While some date to the 18th Dynasty, corresponding to the dates of Structures 2 and 3 at the site, the majority of the pottery is from the Ramesside period, finding parallels both at 2-T-62/1 and at Amara West, with some Post-New Kingdom pieces also represented. This raises an interesting consideration into how long 2-S-50 was in use. Furthermore, Structure 1 is the one building at the site which yielded Nubian-style ceramics; the earlier Structures 2 and 3 from the heyday of colonial rule in Nubia had a predominantly Egyptian-style ceramic corpus.

3.2.2. Stone Villages

There are a number of sites on the west bank identified as stone villages despite being largely buried beneath sand. 2-T-53, 2-T-57 and 2-T-69 (

Figure 3) are very similar to each other and include architectural remains, such as dry-stone walls, as well as plenty of ceramics, particularly amphorae, storage vessels and dishes dating to the 10th–8th centuries BCE. Therefore, the surface ceramics evidence alone, with no excavations conducted so far, already suggests the sites were used in the Pre-Napatan period (see below).

2-T-53 is the smallest of the stone village sites and extends across approximately 10 hectares. In the 1970s, Vila described six rectangular and three circular structures with dry-stone architecture. One of the structures was excavated in the 1970s (

Vila, 1977a, p. 114). Today, the structures are partly destroyed and the stones are no longer in situ (

Figure 7). Significantly, the site also has a number of large stone walls (see

Budka et al., 2025, fig. 11). Although these were not noted by Vila, they also appear at the other sites. The DiverseNile project has achieved a high level of success in using remote sensing techniques to identify the presence of additional structures at several sites previously documented by Vila and the 1970s survey team. A significant proportion of these structures would have been considerably challenging to identify on the ground given the scattered nature of the archaeological evidence in a sandy-dune landscape (see above).

3.2.3. Stone Walls and Irrigation Features

Stone walls, part of Napatan settlements such as 2-T-53, can also be found at other sites, especially on the west bank. In the MUAFS concession, the stone walls appear to have been erected during almost all phases of human settlement in the region, from Kerma through the New Kingdom to the Napatan, Medieval and Post-Medieval periods (see

Budka et al., 2023). In the case of the earlier walls associated with Kerma sites, the arrangement of these walls along and within the paleochannels suggests that they may have served as wadi flood protection walls. This is particularly significant because Woodward and his team demonstrated that the environmental conditions of this region have changed significantly over time (see

Woodward et al., 2017). Dalton and his colleagues assume that the drying up of the water channels in the region took place during the 18th Dynasty but no later than 1000 BCE. This claim is based on the dating of sites along the main paleochannel in the Amara West district according to OSL and C14 dates (

Dalton et al., 2023; see also

Budka et al., 2025). However, the fact that so many of the walls in the MUAFS concession have now been identified as dating to the Napatan period raises a number of questions.

A connection between some of these stone walls and nearby circular structures can often be observed in Attab and Ginis. While some of these circular structures were probably huts, others with a small diameter of 1.2 to 2 m could also be related to irrigation. This hypothesis was recently proposed for Site 2-T-67 in Ginis West (

Vila, 1977a, pp. 93–96), which consists of three basins and channels (

Figure 8) associated with post-flood irrigation, as observed by

Dalton et al. (

2023).

The re-identification of the site on the ground in 2025 very much supports, if not confirms, this hypothesis. The circular structures recorded at 2-T-67, one of which was surrounded by a stone enclosure, most likely served as wellheads for shadufs (irrigation devices for lifting water). A similar interpretation could also be possible for other circular structures, for example, those at Site 2-T-53. The results of our remote sensing analysis suggest that in contrast to the rectangular structures, these circular structures are predominantly found in lower-lying areas and not on hills (see

Budka et al., 2025). As such, a connection between post-flood irrigation and the stone structures is highly probable and further investigations into the dynamics of the seasonal Nile channels and the expansion of agricultural land are needed.

Vila dated the channels at Site 2-T-67 to the New Kingdom period based on a complete ceramic bowl. However, this intact bowl is now in the Sudan National Museum in Khartoum and re-analysis during the DiverseNile project (

Figure 9) determined it is not of New Kingdom but rather of Pre-Napatan date.

3.3. Example of Cemetery Site

As previously stated, a primary outcome of the 2022 excavation was the confirmation that cemetery 2-T-13/GiE 002 in Ginis East definitively postdates the New Kingdom era and was in use during the 10th–8th centuries BCE. Feature 2 in Trench 4 (

Figure 10) proved to be of particular interest and exhibited slight differences to the other documented graves. These differences included the of mud-brick remains, and a much deeper pit with a side niche towards the south. Furthermore, the grave was evidently utilised in different phases. The oldest burial was unearthed in an extended position in the southern niche of the grave. The skeleton was partially displaced during the looting that took place in antiquity; however, it remains largely intact. The presence of remnants of mud-bricks, which were previously obstructing the niche, shows close parallels with graves at Missimina (

Vila, 1980), particularly in terms of material culture such as a cowry shell pendant and ceramics, especially red-rim dishes.

One complete small-sized Marl clay vessel found with one of the earliest burials of the grave is of particular interest (

Figure 11). MUAFS 065 is made of an Egyptian Marl clay of type A4 according to the Vienna System and finds close parallels both in Egypt and in Nubia, for example, in Tombos (

Buzon & Smith, 2023, p. 627, fig. 4c). As recently stressed by Michele Buzon and Stuart T. Smith, the comparison of C14 dates with ceramics from the same burials at Tombos has indicated that certain Egyptian-imported pottery types such as MUAFS 065, should either be dated earlier or have longer chronological ranges than was previously thought (

Buzon & Smith, 2023, p. 626).

In conclusion, the nature of the site 2-T-13/GiE 002 proved to be more complex than initially assumed by Vila. The presence of pit burials was confirmed, but further investigation also revealed the presence of pits with side chambers sealed with mud-bricks, well attested at other sites during the Pre-Napatan and Napatan periods.

3.4. Ceramic Production

In order to undertake a comprehensive analysis of ceramics from Pre-Napatan Nubia, it is essential to consider the developments that occurred prior to this period. Recent research on sites such as Sai (

Budka, 2020a) has illustrated the complexity of local pottery workshops and traditions in Nubia during the New Kingdom colonial rule. The local production of ceramics can be categorised into two distinct classifications: (1) wheel-thrown predominantly Egyptian-style Nile clay vessels and (2) handmade Nubian vessels. In addition to these two main types, so-called ‘hybrid products’ were also produced, combining elements of both styles to create new and innovative forms (

Budka, 2025).

The ceramic production in Nubia following the colonial period exhibited remarkably similar patterns, albeit with significant shifts and dynamics. As with earlier pottery, the predominant clay used is Nile clay, and both wheel-made and handmade wares are found. In addition to local production, there is also evidence of the import of vessels from Egypt and other regions. This includes predominantly Marl clay vessels, such as the complete jar mentioned above from cemetery 2-T-13/GiE 002 (

Figure 11). Rose stated the following: ‘Early Kushite pottery includes a wide range of forms that show interplay between wheel-made, handmade and imported vessels’ (

Rose, 2019, p. 692). The material unearthed from recent excavations in the Attab to Ferka region includes evidence for this interplay as early as the Late New Kingdom, complemented by the appearance of new, innovative products, similar to the ‘hybrid’ vessels found in New Kingdom contexts.

For instance, the pottery from Site 2-T-62/1 exemplifies certain intriguing regional developments in wheel-thrown ceramics in Nubia during the Late New Kingdom. As illustrated in

Figure 12, this pottery assemblage features both conventional late Ramesside dishes and bowls (bottom of

Figure 12) alongside ‘hybrid’ variants (top of

Figure 12). The latter emulate the form of the red-rim Egyptian-style wheel-made versions, yet they are handmade and possess slightly thicker walls. Analogous examples have been documented from Amara West (

Gasperini, 2023, pp. 75–76, cat. 170). Consequently, it seems probable that the observed characteristics of pottery from 2-T-62/1 and Amara West correspond to an initial phase in the evolution of the distinctive forms of Pre-Napatan pottery in Nubia following the New Kingdom collapse. This phase is characterised by a marked transition between wheel-thrown and handmade techniques, suggesting a significant transformation in ceramic production methods.

A comparable innovation in pottery production can be found in the southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age IIB/III, as outlined by Ido Koch. He demonstrated that in a similar context after a period of colonisation the copying process, technological progress and the ‘local ability to accept technological advantages alongside some sort of specialisation in several workshops’ (

Koch, 2021, p. 95) were all evident.

4. Discussion

In order to better understand the multifaceted and gradual process of the so-called collapse of the New Kingdom in Nubia, it is necessary to evaluate the archaeological record in the period preceding, during and following the end of colonial rule. A combined socioecological (describing the complex, dynamic and coupled relationships between past human societies and their surrounding natural environments) and sociocultural approach is promising in reconstructing postcolonial Nubia and its sociocultural transformation (

sensu Winter, 2024) in the period after the New Kingdom.

One of the most evident changes that ensued following the end of the New Kingdom period is the paucity of substantial information regarding large settlements in northern Sudan, such as the former New Kingdom urban centres. Notwithstanding the considerable progress that has been made in recent years in archaeological fieldwork in Sudan, the question of Pre-Napatan and Napatan settlements remains largely unresolved. The vast majority of archaeological evidence for these periods is from cemetery sites. Derek Welsby has emphasised that despite the survival of numerous New Kingdom sites, the intricacies, formation and settlement patterns of Napatan settlements remain ambiguous because we do not know what happened in the so-called Dark Age (

Welsby, 2019). As demonstrated in this paper, new data from the Middle Nile addresses these issues and facilitates a novel perspective on cultural and societal transformations at the close of the Egyptian New Kingdom in colonial Nubia.

Several research questions underscore the significance of the evidence presented from the hinterland of Amara West and Sai Island in the Attab to Ferka region. The presence of dry-stone walls that extend from the Kerma and Napatan periods along with substantial mud-brick structures dating to the Late New Kingdom attest to the region’s enduring architectural heritage. The Attab to Ferka region has the potential to yield insights into the dynamics of settlement patterns in relation to agricultural and irrigation-based subsistence strategies. In this context, a socioecological approach, incorporating dynamic riverscapes (see

Woodward et al., 2017) and addressing questions such as the cultivation of winter or summer crops (see

Pope, 2018), should ideally be combined with a sociocultural approach, focusing on the actual communities inhabiting the region.

The case studies presented above illustrate the general paucity of knowledge concerning minor towns and sites in the hinterland. Crucially, there is substantial evidence from the Pre-Napatan period, as well as from multiple other periods (see

Figure 2), that clearly demonstrates that there was no interruption in occupation between the New Kingdom and the Napatan era in the Attab to Ferka region. However, further research is required to ascertain the precise nature of this relationship and the actual occupation histories of sites such as 2-T-53 and others.

The discovery of large mud-brick buildings 2-T-62/1 and 2-S-50/1 are especially remarkable as they appear to represent isolated features with a strong focus on an Egyptian-style appearance and limited indigenous pottery. A similar impression was observed at Site 3-P-15 in Kosha West, and of potential significance is an unusual tomb, 3-P-50, nearby in Ginis West, obviously also erected in isolation. Originally interpreted by Vila as an Egyptian New Kingdom tomb in the 1970s (

Vila, 1977a, pp. 145–160), our reassessment of the site revealed evidence for both mixed architecture and material culture, dating to the Late New Kingdom (

Lemos & Budka, 2021, p. 413;

Lemos, 2023, p. 26). 3-P-50 showcases complex grave morphology where Egyptian-style substructures are marked on the surface with Nubian-style tumuli (see

Smith, 2003, pp. 199–200;

Binder, 2017;

2023, p. 12;

Buzon & Smith, 2023).

The extensive use of the cemeteries in Amara West during the Late New Kingdom/Pre-Napatan era contemporaneously with the appearance of isolated mud-brick buildings and an unusual tomb in what would have been the hinterland of this urban centre in the colonial period is unlikely to be a coincidence. This is further supported by the close parallels between tomb 3-P-50 in Kosha West and tomb G244 at Amara West (

Binder, 2014;

2017, pp. 599–606). The latter is the largest multi-chambered tomb at Amara West with a tumulus superstructure, and akin to 3-P-50, it is also situated in what appears to have been an isolated position during the 20th Dynasty. The architectural style of the tombs, their remote location and the rich equipment they contain have been shown to parallel findings from contemporary mud-brick buildings such as 2-T-62/1 and 2-S-50/1 (see

Figure 4). These include a mixture of Egyptian- and Nubian-style material culture as well as the new ‘hybrid’ style. Overall, this would seem to indicate shared characteristics among local elite communities in the Amara, Attab, Ginis and Kosha regions. However, further research is necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of these phenomena, which could also point to the reorganisation of the region, perhaps in relation to a partial collapse as indicated by the ‘failed’ Egyptian administrative town of Amara West. However, it is evident that the combination of Egyptian characteristics and Nubian traditions, coupled with specific innovative elements, was likely influenced by the pre-existing amalgamation of diverse communities that had been established centuries prior. This assertion aligns with the conclusions put forth based on evidence from Tombos (see

Buzon et al., 2016, pp. 296–297;

Buzon & Smith, 2023), but the Attab–Ferka region also stresses the relevance of intra-site differences and of regional variations.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the existence of evidence indicative of continuity from the New Kingdom to the Napatan period has been demonstrated at urban sites such as Tombos, as well as in so-called marginal hinterlands and rural locations such as Attab West. The combined analysis of site distribution, archaeological finds, material culture and historical data can contribute to a more profound understanding of the post-collapse period in this part of Nubia.

New data on ceramic production and consumption provides insight into everyday life and dynamics, suggesting remarkable patterns of transformation and the possible resilience of local communities facing changing climatic conditions and riverscapes in the region (see (

Woodward et al., 2017) for evidence of the drying up of the Nile channels and shrinking of the riparian zone during the Late New Kingdom) as well as the loss of established trade networks in the Late New Kingdom and the subsequent periods. The Late New Kingdom mud-brick structure 2-S-50/1 provides useful evidence for better understanding these changing dynamics. This structure has been shown to contain a slightly higher ratio of Nubian-style pottery in comparison to the 18th Dynasty structures present at the site. This phenomenon could be used to demonstrate the notable endurance of Nubian-style material culture and the resilience of local communities to use mass-produced Egyptian-style ceramics towards the end of the Egyptian colonial rule in the region (see

Ward et al., 2025). However, in view of the recent critique of theories related to resilience (see

Winter, 2024, with references), it could also be argued that the concept of resilience (for terms and definitions related to resiliency and the discussion of their use in archaeology within the framework of the Late Bronze Age collapse see (

Cline, 2024, Table 4); for a general survey about archaeological evidence for community resilience in recent research see also (

Jacobson, 2022)) is here too vague to capture its sociocultural properties and that actual social change at the end of the New Kingdom would also be possible. Furthermore, aspects of hybridity which can be observed at sites such as 2-S-50/1 and 2-T-62/1 could be associated with resistance rather than resilience (for a model for the continuum of resilience, collapse and resistance, see (

Winter, 2024)).

During the Pre-Napatan and Napatan periods, a sudden urban abandonment is not traceable in Nubia, but it can be argued that population densities were low in the Attab to Ferka region. However, there was no shortage of fertile agricultural land, and elites may have competed for control of exchange networks (see the import of Egyptian ceramics and varying amounts of local Nubian wares at the sites). The analysis of local dynamics and shifting powers indicates the likelihood of a pastoral state (see

Emberling, 2014;

Walsh, 2022; cf. also

Cooper, 2020), with agriculture and irrigation practices analogous to those observed during the Kerma Age as indicated by the wadi walls (for a comparison of Kerma settlement patterns with small villages close to farmland to Pre-Napatan patterns near the town of Kawa see (

Welsby, 2017, p. 486)).

In conclusion, a substantial body of evidence indicates that postcolonial Nubia played a pivotal role in the formation of the Napatan empire. Further archaeological investigation is required in this respect. However, the Attab to Ferka case study demonstrates that previously marginalised regions, comprising assumed invisible communities, are in fact significant contributors to cultural dynamics and substantial achievements during the later first millennium BCE. Nevertheless, it is important to consider various geographic and social scales when we try to reconstruct aspects of state formation in Nubia, in particular during the period which was the focus of this paper.