Beyond the Drawing: Ethnography and Architecture as Contested Narratives of the Human Experience of Dwelling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

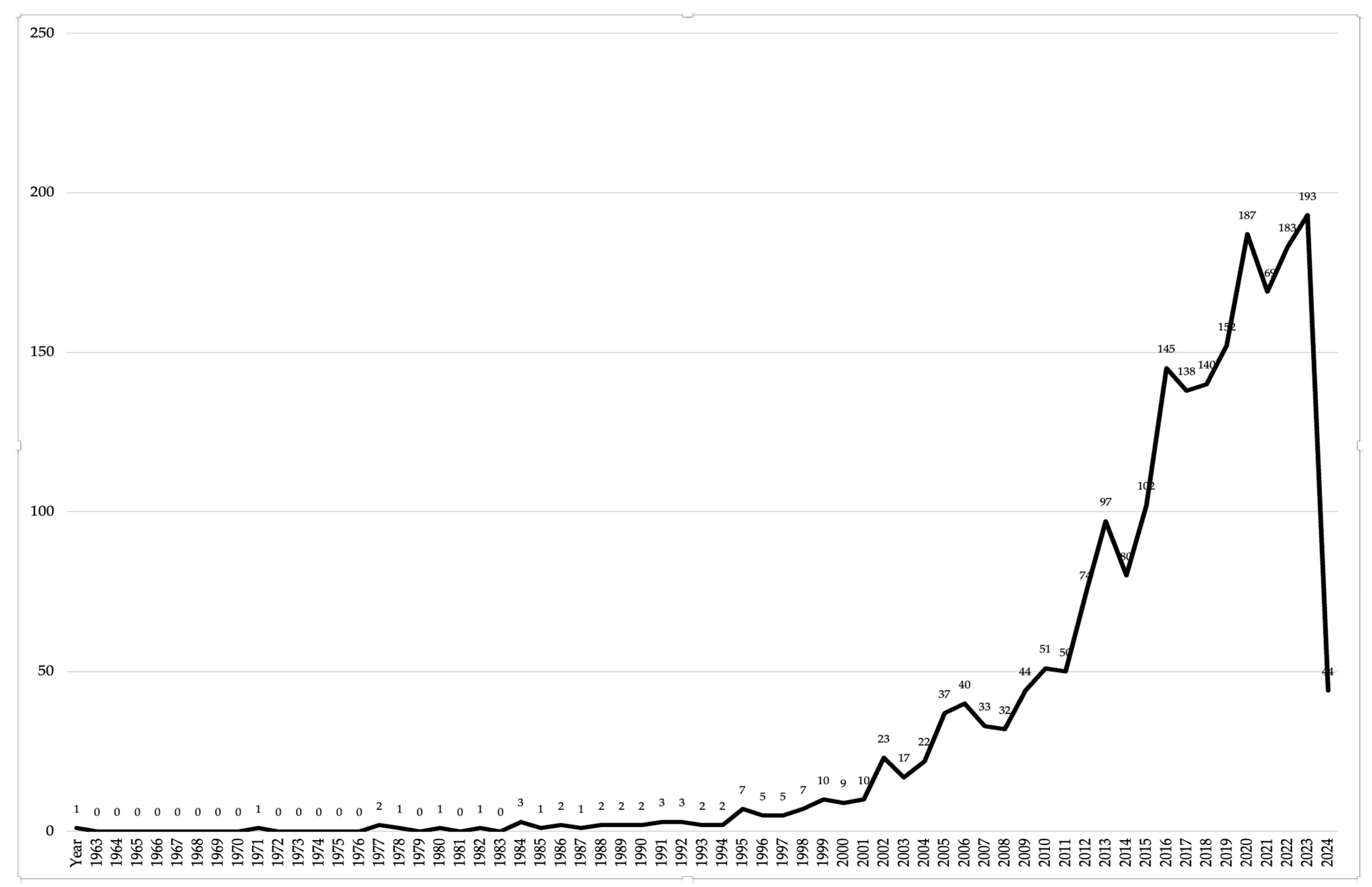

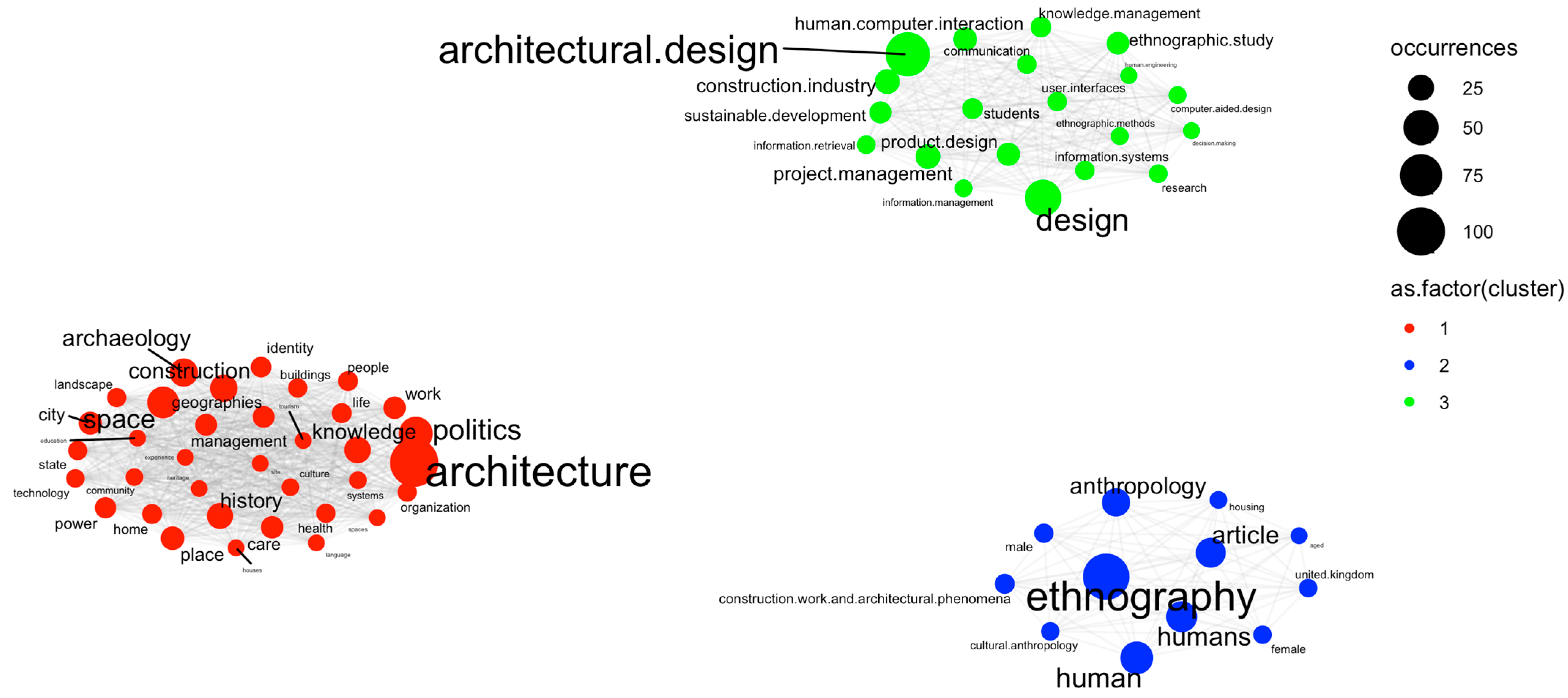

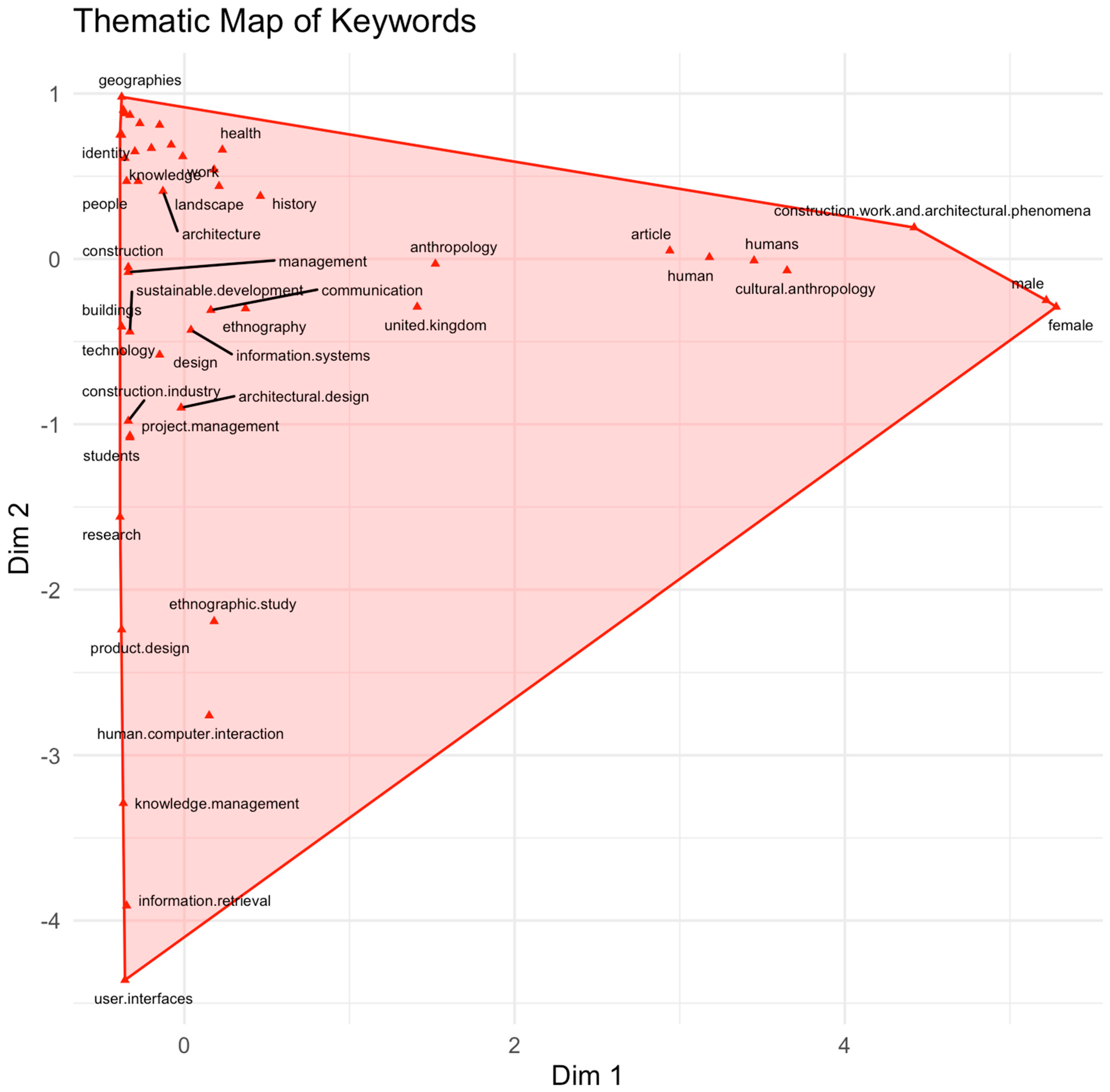

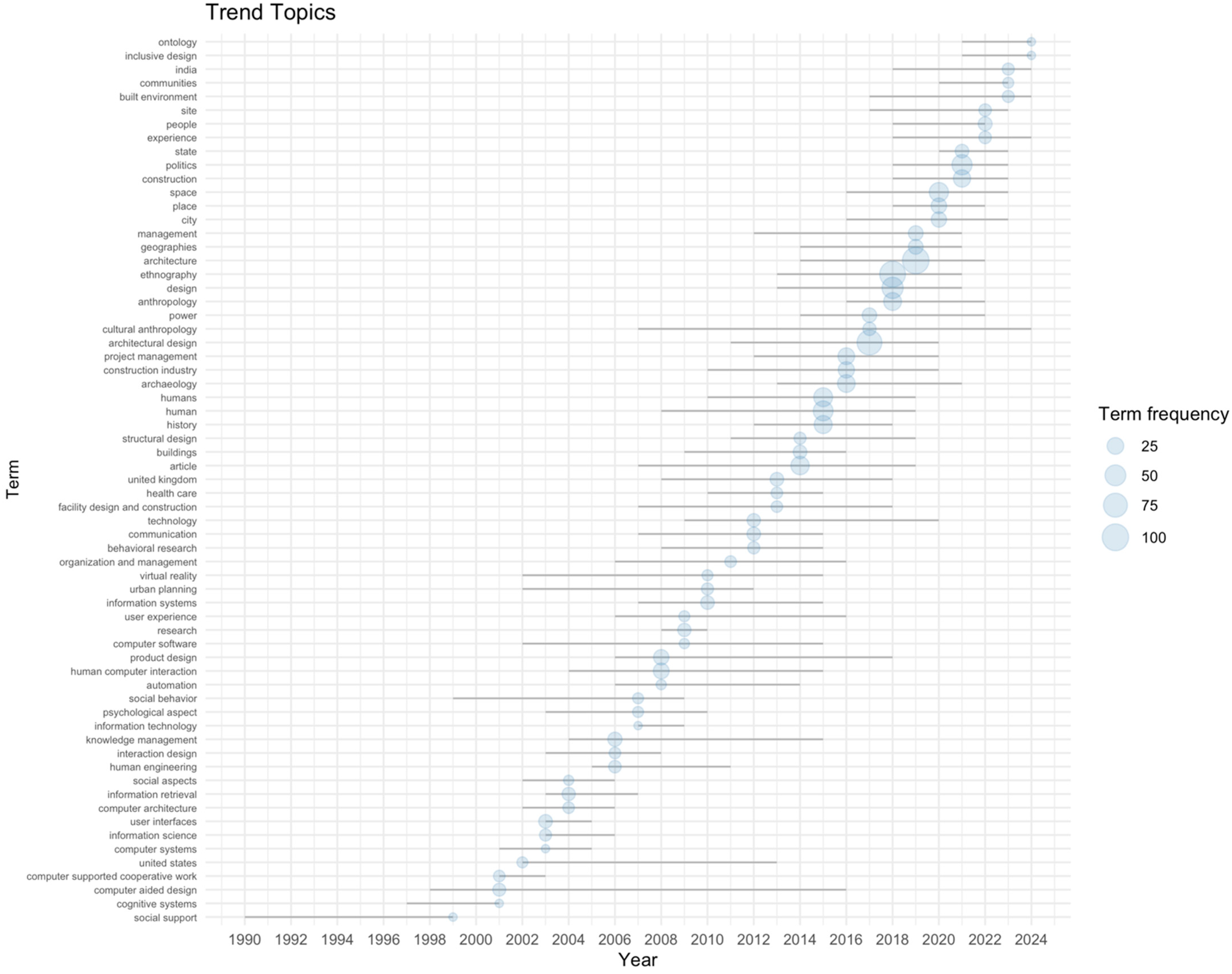

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

3.2. Content Analysis

- Cluster 1: “Practices and Preservation”—[architectural, traditional, forms, practices, preserved]

- Cluster 2: “Ethnography of Policy and Care”—[policies, friendly, manchester, creative, critical]

- Cluster 3: “Digital Ethnographies”—[youtube, streams, digital, interactions, researchers]

- Cluster 4: “Urban Political Economies”—[political, economies, mumbai, planning, methods]

- Cluster 5: “Learning Vernacular”—[education, role, fieldwork, portugal, vernacular]

- Cluster 6: “Pandemic Meetings and Disruptions”—[comparative, lockdowns, meeting, pandemic, study]

- Archaeology, Ritual and Temporality

- Pedagogy and Cognitive Practice

- Urban Life, Infrastructure, and Politics

- Health and Institutional Spatiality

- Domesticity and Everyday Architecture

- Heritage and Vernacular Epistemes

- Embodied Temporalities: Archaeology, Ritual, and Architecture as Living Memory

- Situated Pedagogies: Ethnography as Cognitive and Formative Practice

- Urban Injustices: Everyday Life, Infrastructure, and Spatial Power

- Care and Institutional Devices: Ethnographies of Spatial Well-being

- Dwelling and Subjectivity: Everyday Architectures

- Vernacular Epistemologies: Local Knowledges and Architecture as Translation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ara, D., & Rashid, M. (2016). Imaging vernacular architecture: A dialogue with anthropology on building process. Architectural Theory Review, 21(2), 172–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askland, H. H., Awad, R., Chambers, J., & Chapman, M. (2014). Anthropological quests in architecture: Pursuing the human subject. International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR, 8(3), 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boano, C., & Kelling, E. (2013). Towards an architecture of dissensus: Participatory urbanism in South-East Asia. Footprint, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L., Fry, M.-L., & Previte, J. (2015). Strengthening social marketing research: Harnessing “insight” through ethnography. Australasian Marketing Journal, 23(4), 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan-Horley, C., Luckman, S., Gibson, C., & Willoughby-Smith, J. (2010). GIS, ethnography, and cultural research: Putting maps back into ethnographic mapping. The Information Society, 26(2), 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, S., Cociña, C., Apsan Frediani, A., Acuto, M., Pérez-Castro, B., Peña-Díaz, J., Cazanave-Macías, J., Koroma, B., & Macarthy, J. (2022). “Emancipatory circuits of knowledge” for urban equality: Experiences from Havana, Freetown, and Asia. Urban Planning, 7(3), 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cociña, C., Frediani, A. A., Butcher, S., Levy, C., & Acuto, M. (2022). Editorial: Addressing urban inequalities: Co-creating pathways through research and practice. Environment and Urbanization, 34(2), 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, J. M., Swan, J. E., McInnis-Bowers, C., & Trawick, I. F. (1996). Methods in Sales Research: Ethnography as a method for broadening sales force research: Promise and potential. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 16(2), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copertino, D. (2014). The tools of the trade: The materiality of architecture in the patrimonialization of ‘Arab houses’ in Damascus. Journal of Material Culture, 19(3), 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranz, G., Lindsay, G., Morhayim, L., & Sagan, H. (2014). Teaching semantic ethnography to architecture students. International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR, 8(3), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshyar, E., & Keynoush, S. (2023). Developing adaptive curriculum for slum upgrade projects: The fourth year undergraduate program experience. Sustainability, 15(6), 4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S. (2014). Solid intentions: An archival ethnography of corporate architecture and organizational remembering. Organization, 21(4), 514–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Mármol, C. (2017). The quest for a traditional style: Architecture and heritage processes in a Pyrenean valley. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 23(10), 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, L. T., Asthana, A. K., Srivastava, P., Omar, I., Rawat, K. K., Sahu, V., Cano, M. J., Costa, D. P., Dias, E. M., dos Santos, N., Silva, J. B., Fedosov, V. E., Kozhin, M. N., Ignatova, E. A., Germano, S. R., Golovina, E. O., Gremmen, N. J. M., Ion, R., Stefanut, S., … Larrain, J. (2016). New national and regional bryophyte records, 46. Journal of Bryology, 38(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, T. (2025). “Why would we want to know that?”: In search of useful questions in a water reuse collaboration project in Cairo. Human Organization, 84(1), 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengler, A. M., & Ezzell, M. B. (2018). Methodological impression management in ethnographic research. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 47(6), 807–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoolachan, J. E. (2016). Ethnography and homelessness research. International Journal of Housing Policy, 16(1), 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J. (2012). The ethnographer as community manager: Language translation and user negotiation. Media International Australia, 145(1), 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachyra, P., Atkinson, M., & Washiya, Y. (2015). ‘Who are you, and what are you doing here’: Methodological considerations in ethnographic health and physical education research. Ethnography and Education, 10(2), 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, P., Abiko, A., Frediani, A. A., & Moraes, O. (2010). Urban upgrading interventions and engaging residents in fuzzy management: Case studies from Novos Alagados, Salvador, Brazil. Habitat International, 34(1), 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K. S. H., Ramsden, B., Haigh, J., & Sharman, A. (2019). Using ethnographic methods to explore how international business students approach their academic assignments and their experiences of the spaces they use for studying. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 14(3), 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. (2024). Interdisciplinary perspective on architectural programming: Current status and future directions. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D. (2023). Political economy of the ‘informal’ housing question: Institutional-hybridity of the postcolonial state. Review of International Political Economy, 30(6), 2052–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, R., & Rabelo, V. C. (2013). Theoretical, methodological, and ethical challenges to the study of immigrants: Perils and possibilities. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2013(141), 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, M., & Smaniotto Costa, C. (2024). The role of collaborative ethnography in placemaking. Humans, 4(3), 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miessen, M. (2011). The nightmare of participation: Crossbench praxis as a mode of criticality. Sternberg Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, W. (2020). The movable center: Geographical discourses and territoriality during the expansion of the spanish empire. In A. Del Sarto, A. Ríos, & A. Trigo (Eds.), The latin american cultural studies reader (pp. 262–290). Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, W. D. (1992a). On the colonization of amerindian languages and memories: Renaissance theories of writing and the discontinuity of the classical tradition. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 34(2), 301–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, W. D. (1992b). Putting the Americas on the map (geography and the colonization of space). Colonial Latin American Review, 1(1–2), 25–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, A., Kostić, M., Zorić, A., Đorđević, A., Pešić, M., Bugarski, J., Todorović, D., Sokolović, N., & Josifovski, A. (2020). Transferring COVID-19 challenges into learning potentials: Online workshops in architectural education. Sustainability, 12(17), 7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Sieburth, M. (2020). Ethical dilemmas and challenges in ethnographic migration research. Qualitative Research Journal, 20(3), 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J. M. (2016). Underlying ethnography. Qualitative Health Research, 26(7), 875–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounajjed, N., Peng, C., & Walker, S. (2007). Ethnographic interventions: A strategy and experiments in mapping sociospatial practices. Human Technology: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans in ICT Environments, 3(1), 68–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M., & Matusiak, B. (2024). Daylighting simulation and visualisation: Navigating challenges in accuracy and validation. Energy and Buildings, 312, 114188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostwald, M. J. (2017). Digital research in architecture: Reflecting on the past, analysing the trends, and considering the future. Architectural Research Quarterly, 21(4), 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottrey, E., Jong, J., & Porter, J. (2018). Ethnography in nutrition and dietetics research: A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 118(10), 1903–1942.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantidi, N. (2013). An ethnographic study of everyday interactions in innovative learning spaces. Open University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J. M. F. (2023). Challenges and current research trends for vernacular architecture in a global world: A literature review. Buildings, 13(1), 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portacolone, E., Covinsky, K. E., Johnson, J. K., Rubinstein, R. L., & Halpern, J. (2019). Walking the tightrope between study participant autonomy and researcher integrity: The case study of a research participant with Alzheimer’s disease pursuing euthanasia in Switzerland. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 14(5), 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, A., Mahamadu, A.-M., & Mahdjoubi, L. (2022). Understanding the challenges of immersive technology use in the architecture and construction industry: A systematic review. Automation in Construction, 137, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, P. W. (2020). Insurgent planner: Transgressing the technocratic state of postcolonial Jakarta. Urban Studies, 57(9), 1845–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifi, Y. (2024). An analysis into East Jerusalem’s housing environment: From social and climatic perspective. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 23(1), 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samura, M. (2018). Understanding campus spaces to improve student belonging. About Campus: Enriching the Student Learning Experience, 23(2), 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B. d. S. (2016). Epistemologies of the South and the future. From the European South—Postcolonialitalia, 17–29. Available online: https://estudogeral.sib.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/35377/1/Epistemologies%20of%20the%20South%20and%20the%20future.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Sliwinska, M. J. (2019). The spirit of public space: Embodied through writing and movement. Journal of Interior Design, 44(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stender, M. (2017). Towards an architectural anthropology—What architects can learn from anthropology and vice versa. Architectural Theory Review, 21(1), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprapti, B. A., Budihardjo, E., Kistanto, N. H., & Tungka, A. E. (2010). Ethnography-architecture in kampong kauman semarang: A Comprehension of cultural toward space. American Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 3(3), 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutt, D., & Pink, S. (2019). Refiguring global construction challenges through ethnography. Construction Management and Economics, 37(9), 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, I., & Crosby, A. (2023). Place-based methodologies for design research: An ethnographic approach. Design Studies, 85, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellinga, M. (2017). A Conversation with architects: Paul Oliver and the anthropology of shelter. Architectural Theory Review, 21(1), 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesa, M., & Vaara, E. (2014). Strategic ethnography 2.0: Four methods for advancing strategy process and practice research. Strategic Organization, 12(4), 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadams, M., & Park, T. (2018). Qualitative research in correctional settings: Researcher bias, western ideological influences, and social justice. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 14(2), 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T. J. (2012). Making organisational ethnography. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 1(1), 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuli, N. G., Maharika, I. F., & Eckardt, F. (2023). The architecture of pesantren: Current issues, challenges and prospect for design framework. Journal of Islamic Architecture, 7(4), 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zallio, M., & Clarkson, P. J. (2021). Inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility in the built environment: A study of architectural design practice. Building and Environment, 206, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abásolo-Llaría, J.; Vergara-Perucich, F. Beyond the Drawing: Ethnography and Architecture as Contested Narratives of the Human Experience of Dwelling. Humans 2025, 5, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans5030024

Abásolo-Llaría J, Vergara-Perucich F. Beyond the Drawing: Ethnography and Architecture as Contested Narratives of the Human Experience of Dwelling. Humans. 2025; 5(3):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans5030024

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbásolo-Llaría, Jose, and Francisco Vergara-Perucich. 2025. "Beyond the Drawing: Ethnography and Architecture as Contested Narratives of the Human Experience of Dwelling" Humans 5, no. 3: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans5030024

APA StyleAbásolo-Llaría, J., & Vergara-Perucich, F. (2025). Beyond the Drawing: Ethnography and Architecture as Contested Narratives of the Human Experience of Dwelling. Humans, 5(3), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans5030024