Community’s House and Symbolic Dwelling: A Perspective on Power

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Complexity of Power

3. Claude Lévi-Strauss’s “House Societies”

4. Northwest Amazon Ethnographic House (Maloca)

Despite these different traditions, in other respects the narrative histories of these two populations show striking features in common, so much so that, in overall terms, one can speak of a shared Upper Rio Negro narrative tradition distributed between different groups with each one producing its own particular version, giving it a particular slant, and interpreting it in line with its own specific identity.[63] (p. 158)

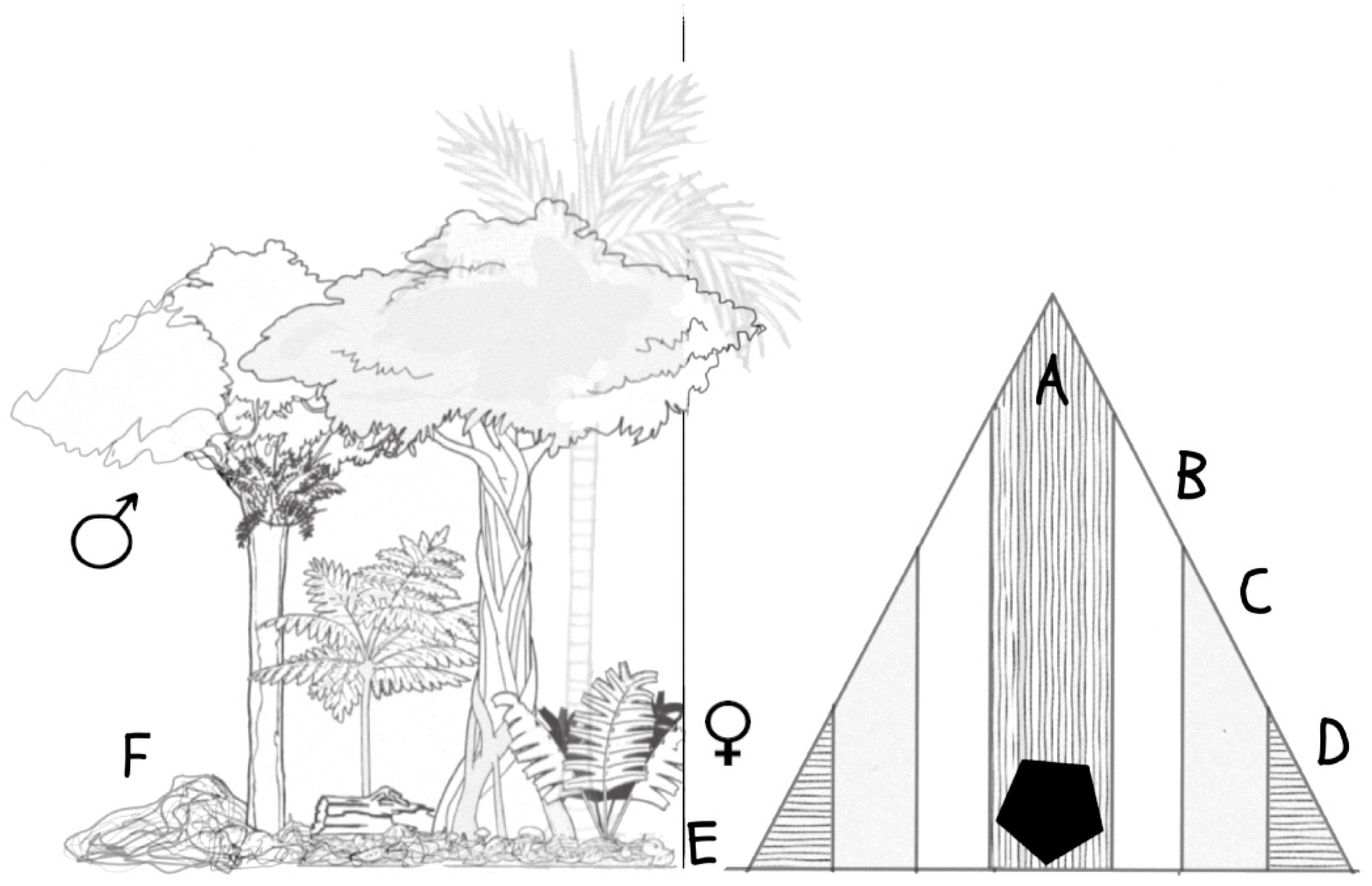

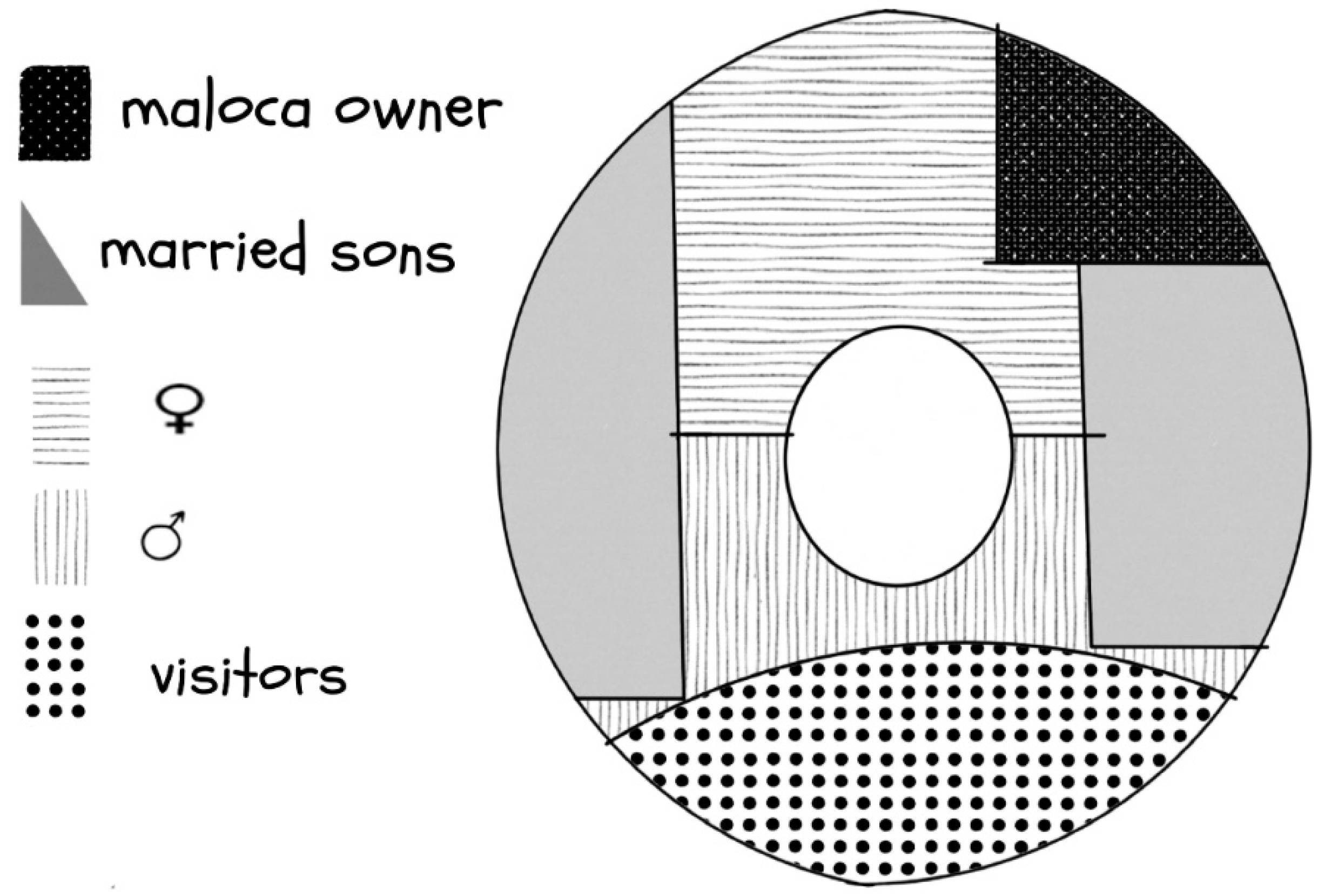

It was a large, substantial building, near a hundred feet long, by about forty wide and thirty high, very strongly constructed of round, smooth, barked timbers, and thatched with the fan-shaped leaves of the Carana palm. One end was square, with a gable, the other circular; and the leaves, hanging over the low walls, reached nearly to the ground. In the middle was a broad aisle, formed by the two rows of the principal columns supporting the roof, and between these and the sides were other rows of smaller and shorter timbers; the whole of them were firmly connected by longitudinal and transverse beams at the top, supporting the rafters, and were all bound together with much symmetry by sipós. Projecting inwards from the walls on each side were short partitions of palm-thatch, exactly similar in arrangement to the boxes in a London eating-house, or those of a theatre. Each of these is the private apartment of a separate family, who thus live in a sort of patriarchal community. In the side aisles are the farinha ovens, tipitfs for squeezing the mandiocca, huge pans and earthen vessels for making caxiri, and other large articles, which appear to be in common; while in every separate apartment are the small pans, stools, baskets, redes, water-pots, weapons, and ornaments of the occupants. The centre aisle remains unoccupied, and forms a fine walk through the house. At the circular end is a cross partition or railing about five feet high, cutting off rather more than the semicircle, but with a wide opening in the centre: this forms the residence of the chief or head of the malocca, with his wives and children; the more distant relations residing in the other part of the house. The door at the gable end is very wide and lofty, that at the circular end is smaller, and these are the only apertures to admit light and air. The upper part of the gable is loosely covered with palm-leaves hung vertically, through which the smoke of the numerous wood fires slowly percolates, giving, however, in its passage a jetty lustre to the whole of the upper part of the roof.[59] (p. 190)

Perhaps the best model for the human geography of the surface of the world-platter would be a series of concentric rings, beginning with that central house pillar; moving out to the walls of the hut itself; and then beyond, to the cleared plaza, a testament to the power of collective human labor to keep the ever-encroaching jungle at bay; then to the house garden and its familiar useful plants; and finally to the bordering lake, river, or stream, where the spirits begin; or in the opposite direction, toward the interior of the dark tropical forest where other spirits dwell.[70] (p. 137)

5. Discussion: Beyond Lévi-Strauss’ Ethnographic House

On the one hand, people and groups are objectified in buildings; on the other hand, houses as buildings are personified and animated both in thought and in life. At one extreme are the lifeless ancestral houses, mountains or tombs, frozen in time but vividly permanent; at the other extreme are those highly animated houses, in a constant state of changing but ultimately ephemeral.[49] (p. 46)

The hierarchical superiority of named houses was marked by their ability to maintain not only a link to their immediate ancestors (through their skull and neck bones and the small carved images), but also a link (through the tavu altar and heirloom valuables) to the founding ancestors of the house complex as a whole, and thus to distant and successive ancestral sources of life and power.[55] (p. 173)

… headmanship of any Wanano village is held by its highest-ranked male. His authority rests on his position as the senior living descendant of the founding ancestor of the local senior sib; he is the “oldest brother” in his generation, known as mahsa wami, “the people’s oldest brother”.[92] (p. 126)

6. Conclusions

The houses and decorated beams are themselves beings. Everything speaks—roof, fire, carvings and paintings; for the magical house is built not only by the chief and his people and those of the opposing phratry but also by the gods and ancestors; spirits and young initiates are welcomed and cast out by the house in person.[98] (p. 43)

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodseth, L. Introduction: Giving up the Geist: Power, history and the culture concept in the long Boasian tradition. Crit. Anthropol. 2005, 25, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.R. Facing power—Old insights, new questions. Am. Anthropol. 1990, 92, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlins, M. Poor-man, big-man, rich man, chief: Political types in Melanesia and Polynesia. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 1963, 5, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, M.H. The Evolution of Political Society; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Service, E. Origins of the state and civilization. In The Process of Cultural Evolution; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, T.K. The evolution of chiefdoms. In Chiefdoms: Power, Economy, and Ideology; Earle, T., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.; Timothy, E. The Evolution of Human Societies; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Feinman, G.M. Size, complexity, and organizational variation: A comparative approach. Cross-Cult. Res. 2011, 45, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Altroy, T.N.; Timothy, K.E.; Browman, D.L.; Lone, D.L.; Moseley, M.E.; Murra, J.V.; Myers, T.P.; Salomon, F.; Schreiber, K.J.; Topic, J.R. Staple finance, wealth finance and storage in the Inca political economy. Curr. Anthropol. 1985, 26, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinman, G.M. A dual-processual perspective on the power and inequality in the contemporary United States: Framing political economy for the present and the past. In Pathways to Power. New Perspectives on the Emergence of Social Inequality; Price, T.D., Feinman, G.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 255–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, C. Introduction: Peer polity interaction and socio-political change. In Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-Political Change; Renfrew, C., Cherry, J.F., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, M.F. Feasting the community: Ritual and power on the Sicilian acropoleis (10th-6th centuries BC). J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2013, 26, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, B. Feasting in prehistoric and traditional societies. In Food and the Status Quest. An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Wiessner, P., Schiefenhovel, W., Eds.; Berghahm Books: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, B. Fabulous feasts. A prolegomenon to the importance of feasting. In Feast. Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics and Power; Dietle, M., Hayden, B., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 23–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, B. The proof is in the pudding feasting and the origins of domestication. Curr. Anthropol. 2009, 50, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, B.; Suzanne, V. Who benefits from complexity? A view from Futuna. In Pathways to Power. New Perspectives on the Emergence of Social Inequality; Price, T.D., Feinman, G.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2012; pp. 95–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, J.; Antrobus, K.; Atencio, S.; Glavich, E.; Johnson, R.; Loffler, G.; Luu, C. Drinking beer in a blissful mood: Alcohol production, operational chains, and feasting in the ancient world. Curr. Anthropol. 2005, 46, 275–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, R.L. The chiefdom: Precursor of the state. In The Transition to Statehood in the New World; Jones, G.D., Kautz, R.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981; pp. 37–79. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, R. What happened at the flash point? Conjectures on chiefdom formation at the very moment of conception. In Chiefdoms and Chieftaincy in the Americas; Redmond, E.M., Ed.; University of Florida Press: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1998; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R. Warfare and state formation: War make states and states make wars. In Warfare, Culture, and Environment; Ferguson, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 329–358. [Google Scholar]

- Service, E. Cultural Evolutionism. Theory in Practice; Holt, Renehart and Winston, Inc.: New York, NY, USA; Toronto, ON, Canada, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Redmond, E. In war and peace. Alternative paths to centralized leadership. In Chiefdoms and Chieftaincy in the Americas; Redmond, E.M., Ed.; University of Florida Press: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1998; pp. 69–103. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, M.W. Ancient Panama. Chiefs in Search of Power; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarrais, E.; Castillo, L.J.; Earle, T. Ideology, materialization, and power strategies. Curr. Anthropol. 1996, 37, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanish, C. The evolution of managerial elites in intermediate societies. In The Evolution of Leadership: Transition in Decision Making from Small-Scale to Middle-Range Societies; Vaughn, K., Eerkens, J., Kanter, J., Eds.; School of American Research: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2009; pp. 97–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schortman, E.M. Networks of power in archaeology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2014, 43, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumley, C.L. A dialectical critique of hierarchy. In Power Relations and State Formation; Patterson, T.C., Gailey, C.W., Eds.; American Anthropological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; pp. 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Crumley, C.L. Alternative forms of social order. In Heterachy, Political Economy and the Ancient Maya. The Three Rivers Region of the East-Central Yucatan Peninsula; Scarborough, V.L., Valdez, F., Jr., Dunning, N., Eds.; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2003; pp. 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Crumley, C.L. Heterarchy and the analysis of complex societies. Archaeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 2008, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K. Neither hierarchy nor network: An argument for heterarchy. People Strategy 2009, 32, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wiessner, P. The vines of complexity: Egalitarian structures and the institutionalization of inequality among the Enga. Curr. Anthropol. 2002, 43, 233–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drennan, R.D.; Peterson, C.E.; Fox, J.R. Degrees and kinds of inequality. In Pathways to Power: New Perspectives on the Emergence of Social Inequality; Price, D., Feinman, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, R.E.; Feinman, G.M.; Kowalewski, A.; Peregrine, P.N. A dual-processual theory for the evolution of Mesoamerican civilization. Curr. Anthropol. 1996, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palmer, C.T.; Coe, K.; Steadman, L.B. Reconceptualizing the human social niche how It came to exist and how it is changing. Curr. Anthropol. 2016, 57, S181–S191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanton, R.E.; Fragher, L. Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-Modern States; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, R.E.; Fargher, L.F. The collective logic of pre-modern cities. World Archaeol. 2011, 43, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanish, C. The Evolution of Human Co-Operation: Ritual and Social Complexity in Stateless Societies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, R.D.; Peterson, C.E. Patterned variation in prehistoric chiefdoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3960–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drennan, R.D.; Peterson, C.E. Challenges for comparative study of early complex societies. In The Comparative Archaeology of ComplexSsocieties; Smith, M.E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Godelier, M. In and Out of the West. Reconstructing Anthropology; University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wason, P.K. The Archaeology of Rank; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boix, C. Political Order and Inequality: Their Foundations and Their Consequences for Human Welfare; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, K.M.; Shepard, E.E. Building wooden houses: The political economy of plankhouse construction on the southern Northwest Coast of North America. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2019, 53, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, R.A. Heirlooms and house: Materiality and social memory. In Beyond Kinship. Social and Material Reproduction in House Societies; Joyce, R.A., Gillespie, S.D., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sissons, J. Building a house society: The reorganization of Maori communities around meeting houses. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2010, 16, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, M. The hearth-group, the conjugal couple and the symbolism of the rice meal among the Kelabit of Sarawak. In About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond; Carsten, J., Hugh-Jones, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Waterson, R. Houses and hierarchies in island Southesat Asia. In About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond; Carsten, J., Hugh-Jones, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, C. The Way of the Masks; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, J.; Hugh-Jones, S. Introduction. About the house: Lévi-Strauss and beyond. In About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond; Carsten, J., Hugh-Jones, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ruibal, A.; Ruiz-Gálvez, M. House societies in the ancient Mediterranean (2000–500 BC). J. World Prehistory 2016, 29, 383–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R. Archaeology of Domestic Architecture and Human Use of Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringham, R. The continuous house: A view from the deep past. In Beyond Kinship. Social and Material Reproduction in House Societies; Joyce, R.A., Gillespie, S.D., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, K.; Joyce, M. The Creation of Inequality. How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery and Empire; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kirch, P. Temples as “Holy Houses”: The transformation of ritual architecture in traditional Polynesian societies. In Beyond Kinship. Social and Material Reproduction in House Societies; Joyce, R.A., Gillespie, S.D., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, S. The Tanimbarese Tavu: The ideology of growth and the material configuration of houses and hierarchy in an Indonesian society. In Beyond Kinship. Social and Material Reproduction in House Societies; Joyce, R.A., Gillespie, S.D., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, S. Houses and hierarchy: The view from South Moluccan society. In About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond; Carsten, J., Hugh-Jones, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 170–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S.D. Lévi-Strauss: Maison and société a maisons. In Beyond Kinship. Social and Material Reproduction in House Societies; Joyce, R.A., Gillespie, S.D., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 22–52. [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen, T. The North-West Amazon: Notes of Some Months Spent among Cannibal Tribes; Constable & Company Ltd.: London, UK, 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, A.R. A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Río Negro; Haskell House Publishers, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Grunberg, T. Dos Años Entre Los Indios; de Bogotá, S., Ed.; Editorial Universidad Nacional: Lima, Peru, 1995; Volume I–II. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, I. The Mouth of Haven: An Introduction to Kwakiutl Religious Thought; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones, S. The origin of night and the dance of time: Ritual and material culture in Northwest Amazonia. Tipití J. Soc. Anthropol. Lowl. S. Am. 2019, 16, 76–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones, S. Writing on stone; writing on paper: Myth, history and memory in NW Amazonia. Hist. Anthropol. 2016, 27, 154–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hammen, M.C. El Manejo del Mundo. Naturaleza y Sociedad Entre Los Yukuna de la Amazonia Colombiana; TropenBos: Caquetá, Colombia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, F. Los Ayawaroa Construyen el Cosmos; Universitas Humanística: Bogota, Colombia, 1991; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, J. The fertile land of the ancestors in the architecture of South Nias, Indonesia. Pac. Arts 2011, 11, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, M.V. Vivienda Indígena: Función socio-política de la Maloca. Rev. Proa 1983, 323, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, G. The Forest Within. The World-View of the Tukano Amazonian Indians; Themis Books, Green Books, Fozhole, Dartington; COAMA Programme & Gaia Foundation: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M.S.D. Sobre Casas, Pessoas e Conhecimentos: Uma Etnografia Entre os Tukano Hausirõ e Ñahuri Porã, do Médio Rio Tiquié, Noroeste Amazônico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, P. The cosmic zygote. In Cosmology in the Amazon Basin; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, R.M. Mysteries of the Jaguar Shamans of the Northwest Amazon; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chagnon, N.A. Yanomamo, the Fierce People; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, V.M. Notas etnográficas sobre el cosmos Ufania y su relación con la maloca. Maguare 1983, 2, 177–210. [Google Scholar]

- Arhem, K. Makuna Portrait of an Amazonian People; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arhem, K. Observations on life cycle rituals among the Makuna: Birth, initiation, death. Ann. Ethnogr. Mus. Gothenbg. 1980, 3, 10–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández de Alba, G. The Achagua and their neighbors. In Handbook of South American Indians; Steward, J.H., Ed.; U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1959; pp. 399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Cayón, L. En las Aguas del Yuruparí. Cosmología y Chamanismo Makuna; Universidad de Los Andes: Bogotá, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, F. Por el Camino de la Anaconda Remedio; Universidad Nacional, Colciencias: Bogotá, Colombia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, I. Cubeo Hehénewa Religious Thought. Metaphysics of a Northwestern Amazonian People; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones, S. Inside-out and back-to-front: The androgynous house in northwest Amazonia. In About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond; Carsten, J., Hugh-Jones, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 226–252. [Google Scholar]

- Arhem, K. Los Macuna en la historia cultural del Amazonas. Inf. Antropol. 1990, 4, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.D. Social equality and ritual hierarchy: The Arawakan Wakuenai of Venezuela. Am. Ethnol. 1984, 11, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, M. Is there religion at Catalhoyuk … or are there just houses? In Religion in the Emergence of Civilization: Çatalhöyük as a Case Study; Hodder, I., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 146–162. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, J. Houses in Langkawi: Stable structures or mobile homes? In About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond; Carsten, J., Hugh-Jones, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S.D. Beyond kinship: An introduction. In Beyond Kinship. Social and Material Reproduction in House Societies; Joyce, R.A., Gillespie, S.D., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, E.; Newman, J.R. Godel’s Proof; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Boric, D. First households and “house societies” in European prehistory. In Prehistoric Europe. Theory and Practice; Jones, A., Ed.; Willey-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 109–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, V. The houses of the Mebengokre (Kayapo) of central Brazil—A new door to their social organization. In About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond; Carsten, J., Hugh-Jones, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 206–225. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, P. The Life of the Longhouse: An Archaeology of Ethnicity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wijk Ivo, M.; van de Velde, P. House societies or societies with houses? Bandkeramik kinship and settlement structure from a Dutch perspective. In A Human Environment. Studies in Honour of 20 Years Analecta; Klinkenberg, M.V., van Oosten, R.M.R., van Driel-Murray, C., Bakels, C., Eds.; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, G. Aboriginal economies in stateless societies. In Exchange Systems in Prehistory; Earle, T.K., Ericson, J.E., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Chernela, J.M. The Wanano Indians of the Brazilian Amazon: A Sense of Space; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, M.W. Access to Origins: Affines, Ancestors and Aristocrats; University of Texas press: Austin, TX, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, G. Chamanes de la Selva Pluvial: Ensayos Sobre los Indios del Noroeste Amazónico; Themis Books: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijt, I. The regeneration of life Neolithic structures of symbolic remembering and forgetting. Curr. Anthropol. 2008, 49, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lillios, K. Objects of memory: The ethnography and archaeology of heirlooms. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 1999, 6, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinman, G.M. The emergence of inequality. A focus on strategies and processes. In Foundations of Social Inequality; Price, T.D., Feinman, G.M., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss, M. The Gift. The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies; Cohen & West Ltd.: London, UK, 1963; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mora, S. Community’s House and Symbolic Dwelling: A Perspective on Power. Humans 2022, 2, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans2010001

Mora S. Community’s House and Symbolic Dwelling: A Perspective on Power. Humans. 2022; 2(1):1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans2010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleMora, Santiago. 2022. "Community’s House and Symbolic Dwelling: A Perspective on Power" Humans 2, no. 1: 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans2010001

APA StyleMora, S. (2022). Community’s House and Symbolic Dwelling: A Perspective on Power. Humans, 2(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans2010001