1. Introduction: Hunter-Gatherers and Anarchic Solidarity

The emergence of a new global anarchist social movement in the past twenty-five years was paralleled by a revival of anthropological interest in anarchy [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The anarchist framework has proven beneficial for both sides: while anthropologists have used this framework to address such classic questions as those addressing hunter-gatherer sociality, the “society issue”, and the relationship of society and state [

4,

5], new anarchists have increasingly turned to anthropological work on small-scale indigenous groups as viable models and examples of alternative, non-hierarchical, political organizational structures and anti-authoritarian modes of governance [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, is this assumed affinity between the ethics and aspirations of anarchism and small-scale societies justified?

In the context of Southeast Asia, interest in anarchist anthropology has been marked by the works of Scott [

4] and Gibson and Sillander [

5]. In the latter work, various authors often rely on impressionistic and descriptive phrases such as “open-aggregated”, or “loosely aggregated” society, “gregarious sociality”, “week ties”, “fellowship”, “companionship”, “multistranded relations”, “subjective membership”, and “intensely sociable community” to express the assumed affinity of anarchist values and the sociality of small-scale societies [

9,

10]. In this article, however, I will focus on one construct, “cooperative autonomy”, because this concept precisely summarizes both the anarchist features of the sociality of small-scale societies and the aspirations of anarchists. It communicates the “ultimate projection of both liberalism and socialism” [

8] (p. 1) better than other formulations.

Although several authors in the Gibson and Sillander volume allude to “cooperative autonomy” (e.g., [

9,

11,

12]), the concept is developed in detail by Kirk Endicott [

13] in a chapter discussing the ethics and social organization of Batek foragers of the Malay Peninsula. In this chapter, Endicott challenges the assumption that “because individual interests diverge or conflict, societies must have ways of constraining the actions of individuals or else the society will fly apart and anarchy will ensure” (p. 62). He states that Batek “emphasize the autonomy of all individuals and married couples” while, owing to “centripetal forces”, they also maintain “a strong sense of community” (p. 65). Among Batek, the ethical principles that promote solidarity include the obligation to respect and aid others, as well as nonviolence and a lack of interpersonal competition (p. 65).

“Cooperative autonomy” not only successfully reconciles two opposing traditions in the scholarship of egalitarian hunter-gatherers—one focusing on collectivism as in “primitive communism” [

14], while the other emphasizing individual autonomy [

15])—but also unites foragers and small farmers within a single interpretive framework. The chapters reflecting the perspective of anarchist anthropology in the Gibson and Sillander volume break with the tradition that differentiates the indigenous social systems of Southeast Asia as representing distinct approaches to organization [

16,

17]. As Macdonald [

10] (p. 31) argues, similarities in sociality in terms of “strict egalitarianism and radical sharing ethos” suffice to undermine the distinction between foragers and small farmers of the region. “Cooperative autonomy” signifying both personal autonomy and social solidarity [

11] is eminently suited to capturing these similarities.

Anarchism is an undoubtedly complex theoretical orientation [

6]. Nonetheless, despite differences in scale, aspirations, and historical circumstance, “cooperative autonomy” clearly resonates with anarchist ideals [

18]. Its principles of relating and practices of community organization are particularly evident in in the “lived anarchic tradition” of Spanish anarcho-syndicalism prior to the 1936 Civil War—one of the few and best-documented instances when anarchic ideas were consistently put in practice [

19] (p. 4). Common elements in the sociality of indigenous groups and anarcho-syndicalism may be summarized in the principles of heterarchy, bottom-up organization, voluntary social relations, and egalitarian ethic. Even though they emphasized voluntary membership, anarchist communities did not simply advocate libertarian principles [

6]. As among Batek, in the anarchist communities of Spain, self-sufficiency and individualism complemented and supported, rather than undermined, cooperation and communalistic ideals (p. 48). As Ward asserts, anarchists strive to “[protect their] own autonomy and associating with others for common advantages” [

8] (p. 2). As opposed to communists of the era, the anarchists of Spain aspired to organize communities and coordinate activities from the bottom-up through the cooperation, conviction, and self-initiated action of autonomous individuals whose personal responsibility made external authority structures unnecessary and obsolete. Bookchin observes that Spanish anarchists “never ceased to emphasize the need for decentralization… [and] control from below, and direct action” [

19] (p. 47). These anarchist ideals correspond to Maeckelbergh’s notion of horizontalism as “the active creation of non (less)-hierarchical relations” [

20] (p. 31, cited by Blunden [

21] (p. viii). Anarcho-syndicalists’ “affinity groups” mirror the friendship-based networks and “companionship” of mobile foragers [

22,

23]. Finally, as hunter-gatherers, the anarchists of Spain were guided by the principle of ethical egalitarianism, an aversion to being dominated [

15]. Driven by their “programmatic commitment” to the “Idea”, anarcho-syndicalists were expected to perform their role without external pressure, duress, or even direct leadership [

19] (pp. 3–5, emphasis in the original).

While the utility of “cooperative autonomy” in linking manifestations of anarchic solidarity in various contexts is evident, at the time of the Endicotts’ research in the 1970s, Batek still lived the lifestyle of mobile forest collectors. Since then, in Peninsular Malaysia, as elsewhere, most nomadic foragers have been resettled in villages that restrict their movements and livelihood as well as impact their social relations. This article will examine the extent to which one such group, the Lanoh of Upper Perak, Malaysia, relied on and utilized the principles and practices of “cooperative autonomy” to cope with and respond to organizational challenges following resettlement. How newly sedentary foragers negotiate the unprecedented complications of regroupment can be instructive to anarchist communities and enrich the anthropological concept of community. In particular, I am interested in finding out if, under these circumstances, the ethical principles outlined in “cooperative autonomy” lead to the development of “civil society” among people whose previous social organization has been described as “open aggregation”, that is, as a system “in which all groups beyond the domestic family are loosely defined, ephemeral, and weakly corporate” [

18] (p. 1).

“Civil society” has been defined in terms of interlocking interests [

13], as the organization between the levels of household and state [

24]. Historically, community building has presented a problem for anarchist communities comprised of face-to-face citizen groups that transcend kinship-based organization. Aspirations to build horizontal organization and accomplish decentralized affinity groups without formal leaders were undermined by interpersonal tensions, clashes of disagreement and strife—often about leadership. Arbitrarily acting cliques and factions often led to fragmentation and disintegration in anarchic communities [

3,

6]. Under the conditions of regroupment and resettlement, foragers face a similar challenge to establishing amity [

11] in the absence of kinship ties among members. Will values including respect, sharing, and fellowship associated with “cooperative autonomy” aid newly sedentary foragers in this transition?

My ethnographic fieldwork among Lanoh, one of the indigenous Orang Asli groups of rainforest collector traders in Peninsular Malaysia, lasted for fourteen months in 1998–1999. Apart from participant observation, I studied time allocation using spot checks and economic decision-tree analysis. As part of this study, I collected data on decisions concerning participation in contract work, paddy planting, and the decision to join POASM (Peninsular Malaysia Orang Asli Association). Shortly after my arrival, I started to record unstructured, informal life history narratives in the main resettlement village of Air Bah as well as in nearby Orang Asli communities with ties to the village. The interviews were initiated by Lanoh who revealed their respect for individual autonomy when they suggested at the outset that to “really” get to know people, I should conduct personal interviews. These life history interviews were later analyzed for what they revealed of interactions with various parties within as well as outside the village, the history of interpersonal relations, and conditions prior to resettlement. Lanoh, often weary and reluctant to directly express opinions about contemporary events, felt much more at ease when narrating their life stories. As a result, these narratives indirectly conveyed a wealth of information concerning social change, contemporary events and projects, group dynamics, and attitudes towards outsiders—other Orang Asli groups, as well as Chinese, Malays, and Westerners.

Contrary to expectations, these data revealed that though foragers such as Lanoh may share fundamental values associated with anarchic solidarity, they profoundly differ from anarchists in their attitudes toward authority and cooperation. This discrepancy suggests that when it comes to understanding how “cooperative autonomy” operates in various contexts, we need to shift from predominantly emphasizing ethical principles shared by anarchists and small-scale societies to inquiring into how socio-political, economic, and ecological factors impact organization to facilitate or hinder community building.

2. Lanoh Resettlement and Responses to the Communal Challenge

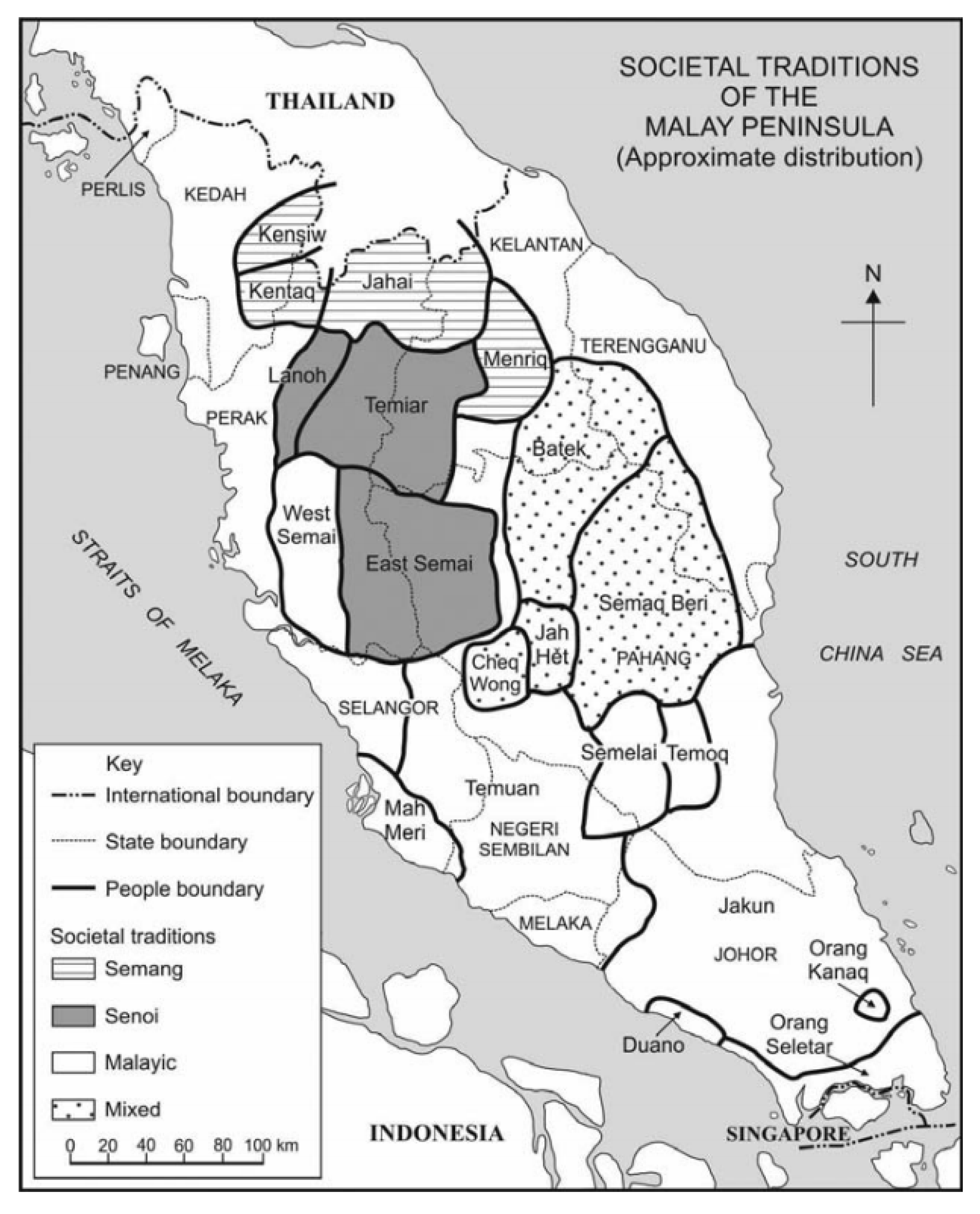

As Central Aslian speakers, Lanoh most likely share historical ties with Senoi horticulturists (

Figure 1). However, based on their lifestyle and social organization, generations of researchers have classified them as Semang, a category of rainforest foragers and traders that, apart from Batek, also includes Chewong, Kensiu and Kintak. Lanoh resettlement occurred over a period of twenty years. The first plans in the 1960s were interrupted because, after a cholera outbreak, people dispersed in small groups to old camp and village sites. The resettlement process resumed in the 1970s, and eventually, in the mid-1980s, Lanoh were regrouped and moved to Air Bah. Air Bah’s status as a resettlement village was clearly established after the Department of Orang Asli Affairs (

Jabatan Hal Ehwal Orang Asli, or JHEOA) erected permanent wooden houses and urged people living in lean-to shelters to move in. By the late 1990s, Air Bah’s population was approximately 200 people. While most identified as Lanoh, the village was also home to a few Temiar individuals who had married women in the village. With the increased number of children per family, women, as well as middle-aged men with large families, became more sedentary than in the past. Mixed-gender work groups became rare. Unlike Batek women [

13], Lanoh women of Air Bah no longer participated in rattan collecting.

Yet, the population was far from established. The membership of the village fluctuated, with people constantly moving in and out, and at the time of my fieldwork, villagers still demonstrated autonomy, flexibility and sharing, and avoided binding commitments. Their lifestyle also retained its fluid mobility—frequent movement, changing of plans, and the immediacy of interpersonal relations. Although it was no longer possible to return to former villages and camp sites, people routinely visited and stayed with family and friends, and, in turn, relatives came to stay in Air Bah. Additionally, men often left the village to pursue rattan and scented wood collecting for periods ranging from days to weeks at a time. During these periods, they maintained temporary camps in the forest. Dwellings in the village also reflected this fluidity. While some families lived in the plank houses, others occupied adjoined lean-to shelters, or built Temiar-style single family-occupancy houses.

Nonetheless, resource depletion, change in settlement structure and composition, as well as pressure from government agencies, contributed to community projects requiring cooperation and organization at a scale far larger than those in semi-mobile villages and mobile camps before resettlement. Though Lanoh continued to pursue traditional forest collecting for trade as well as subsistence hunting, neither of these was possible to the same extent as in the past. As game became scarce near the village, people increasingly needed to rely on cash for food supplies. Air Bah was surrounded by rubber and palm oil plantations as well as vegetable farms that offered cash employment. However, Lanoh men insisted on earning cash from forest work. Despite occasional opportunities for the small-scale collecting of minor forest products, this primarily meant working in the rattan trade. This trade, however, was predominantly increasingly controlled and monopolized by Chinese and Malay subcontractors, who demanded increased outputs that required more extensive coordination than collecting minor forest products.

The structure of Air Bah also differed from that of earlier Lanoh settlements. The resettlement village was larger and more complex in composition than previous Lanoh villages and camps. As a result of regroupment, the village incorporated four kinship groups previously scattered in different areas of the Lenggong Valley in Upper Perak. Two of these cluster’s leaders were soon competing intensely with each other for leadership of the village. These competing leaders attempted to use any means possible, including organizing collaborative projects, to reinforce their position and to emerge as the main leader of the community.

Projects linked to village infrastructure provided several opportunities for the competing leaders to engage the inhabitants of the settlement. For example, the maintenance of the power generator required cooperation and coordination by all. Although the JHEOA had supplied the equipment, a village-wide collection of cash was necessary to purchase fuel for the generator, Additionally, the fresh water supply sourced from the hills depended on the cooperation of households. The village, located about a twenty-minute walking distance from the river Sungai Bah, obtained its water through a gravitational system consisting of bamboo pipes. For the houses downstream to receive water, those upstream needed to collaborate by regularly clearing their water pipes of debris. In addition, communal agricultural and animal husbandry projects were encouraged and supported by the JHEOA in order to foster a more sedentary lifestyle. In the year of my fieldwork, farming in the fields bordering the village was further encouraged by the clearance of old rubber trees from the surrounding hills. Unlike their Senoi horticulturist neighbors, Lanoh are not keen on farming because they consider it a tiresome and monotonous task that interferes with the immediacy offered by various other activities. However, since the logging company that had bought the trees also cleared the surrounding land of the largest trees, people in the village decided to take this opportunity and engage in planting hill paddy at an unprecedented scale. All these projects required serious organization and cooperation, and opposing leaders looked to reinforce their positions by leading and coordinating the workforce.

With regard to Lanoh attitude toward communal projects, we need to differentiate between factors influencing collaboration across versus within kinship groups. In her work on scale-blindness, Nurit Bird-David drew attention to the neglect of kinship-based association among hunter-gatherers [

25,

26]. Kinship-based association was indeed key to understanding some of the limitations on village-wide projects in Air Bah. This constraint particularly impacted women, who almost exclusively associated with and relied on consanguineal kin. Their refusal to spend time with, and even talk to, women whom they considered “lain” (different) prevented village-wide cooperation and contributed to the marginalization of women and their families in the less populous and popular kinship groups. This unwillingness to interact with those considered “lain” was exacerbated by strict and wide-ranging rules of avoidance that extended both to same- and opposite-sex in-laws.

Nonetheless, the men of the village still attempted to establish schedules, assign roles, and obtain the agreement of others through consensus. Unlike women, they frequently associated with other men regardless of kinship group affiliation. They participated in work contracts together and held meetings discussing these contracts and various other matters involving the village. Competing leaders, who withdraw to their houses, however, were conspicuously absent from these meetings of men. Instead, they attempted to organize community projects by the behind-the-scenes persuasion of their younger kin and allies whom they summoned to their houses.

Despite these efforts, cooperative projects in Air Bah quickly collapsed one after the other. The government-initiated animal husbandry project was aborted. The goats delivered to the village either died, were sold, or simply disappeared, abandoned to the forest. People failed to follow up on previously agreed upon schedules in clearing, planting, and harvesting their fields. The water pipes often remained clogged, and people upstream did not mind that families downstream of the pipes were without water for days. The generator continually lacked gasoline, and work leaders repeatedly found themselves reprimanded by Chinese (or Malay) contractors for their inability to organize their “charges” in contract work. Dismayed Temiar horticulturists living in Air Bah frequently and unfavorably compared Lanoh leaders’ inability to organize or persuade others to Temiar leaders’ “cleverness” and “talent” in summoning work for communal effort (gotong royong).

3. Foragers, Farmers, and Anarchic Communities

Sutlive’s classic ethnography of the Iban of Sarawak [

28] offers a useful comparison of swidden cultivators and foragers regarding cooperation related to farming. While labor exchange in agricultural work was common among Iban (p. 75), Lanoh families often expressed that they did not trust others and preferred to work independently. In addition, Iban held more than four dozen farming rituals, each reinforcing social cohesion (p. 66). In contrast, during the farming cycle, Lanoh conducted two farming rituals, with little enthusiasm and participation. Sutlive’s ethnography further demonstrates the role of age-based leadership in achieving synchronicity. He describes that, after all the padi has been harvested, a general meeting is called by the head of the community, the purpose of which is to coordinate everyone’s activities (p. 65). In contrast, in Air Bah, however, it proved impossible to coordinate farming activities. As one of the Temiar men in the village complained, “[Here] the royong begins with twenty people, but at the end, there are only seven people. That is why we do not want it… Look at Pandak… Yesterday, one day (only) he went to plant… Just now, he went looking for what, I do not know… Look at that… He came back late just now… That is why I do not want to help them”.

As noted above, recent studies seeking similarities between anarchic solidarity and small-scale societies have attributed personal autonomy not only to small groups of egalitarian foragers but to the shifting cultivators of Southeast Asia as well [

5]. Yet, the community organization of swidden farmers contrasts both with the management of communal projects in anarchist Spain and the organization of cooperative efforts among collector-traders such as Lanoh. Despite the variation in terms of settlement organization and social structure [

11,

29], in the semi-sedentary societies of Southeast Asia, communal goals and projects are abundant. These, as described by Sutlive [

28], primarily derive from swidden farming (but may also be manifested in communal hunting—for instance, in Temiar elephant hunts) as well as from semi-sedentary communal living lifestyles [

16]. Even in cases where most farming chores are carried out by members of the household, as is the case among Buid, certain activities, such as burning, planting and harvesting tend to be performed by larger groups [

30] (p. 274).

Contrary to the “bottom-up” principle of organization in anarchist communities based on individual conviction, in small-scale horticulturist societies, collective action and activities tend not to be self-directed but overseen and coordinated in a “top-down” fashion by age-based leadership—by individuals commonly referred to as “elders”. Admittedly, authority among the swidden cultivators of Southeast Asia has severe limits. Senoi elders in Malaysia lack authority to order people around. As Dentan notes, one of the Senoi people, Semai, “say explicitly that coercion is physically and spiritually dangerous” [

31] (p. 90). Nonetheless, elders among shifting cultivators use oratory, rhetoric, stories, gentle persuasion, and other means to remind people of their duties and personal obligations, which, in such “delayed-return” systems, mostly derive from kinship ties [

16]. Consequently, claims that these small-scale societies lack, or even defy, “authority structures” at all levels are inaccurate and exaggerated. Though people may resist integration into larger external structures of governance, their attitudes to internal authority are quite dissimilar to that of anarcho-syndicalists. As opposed to anarchists’ ideological imperative to decentralize and defy authority, an equally strong directive impels swidden farmers to obey age-based leadership. Moreover, this same ethical imperative applies to forager-collectors as well.

It might be tempting to explain the breakdown of collaborative action in Air Bah in terms of egalitarian ethic and hunter-gatherers’ opposition to authority. As mentioned earlier, the counter-dominance of hunter-gatherers, especially those with an immediate-return system of production [

15], are thought to be reinforced by practices, ethical principles and institutions, such as network-like organization, stress on friendship over kinship, sharing, and individual autonomy [

14,

15,

32,

33]. Perhaps Lanoh failed to cooperate because they resisted the self-aggrandizement and authoritative style of competing leaders. This explanation, however, is inappropriate for two reasons. First, leaders in Air Bah were never domineering—at most, like Senoi elders, they carefully “advised” others. Second, like shifting cultivators, but unlike anarchists, Lanoh are not against authority in principle. They accepted age-based authority and treated their elders, including competing leaders, with deference. Younger family members in Air Bah wholeheartedly supported kinship cluster leaders and their self-aggrandizing ambitions. While in theory these authority structures could have developed and solidified after resettlement, life history interviews indicate that age-based leadership represented a fundamental authority structure even in previous, mobile times. important for nomadic Lanoh.

People in Air Bah stated that, regardless of fluid social relations and shifting leadership roles, relative age and generational structure defined relationships, ensuring that there was only one leader per group or camp at any one time. While the generational system restricted leadership role to “elders”—that is, married middle-aged or older individuals, with adult, marriageable-aged children—relative age-modulated relationships within generations. While people were uncertain about their, or others’, absolute age, they carefully monitored who was older or younger than themselves. Relative age differences, expressed in kinship terms, defined people’s conduct towards each other and bestowed on those older, even if by a few months, some degree of deference. Relative also age regulated inheritance. For instance, property and belongings such as fruit trees of the deceased were given to the eldest child, or in the absence of this, to the eldest sibling. Additionally, in the past, this principle, combined with easy mobility, helped to resolve any conflict of leadership by ensuring that the younger party gave in and would most likely move away.

Yet, potentially unifying rules promoting cooperation and support of elders notwithstanding, Lanoh differ both from anarchists and tropical horticulturists because they failed to commit to collective goals. According to McKinley [

34] (p. 143, cited by Sillander [

11] p. 162), kinship is a “philosophy… about what completes a person socially, psychologically, and morally, and how that completeness comes about through a responsible sense of attachment and obligation to others”. Just as their swidden cultivator neighbors, Lanoh adhered to this philosophy. They believed in the importance of cooperation and mutual aid and in the desirability to support one’s elders and parents-in-law. Nonetheless, unlike swidden cultivators, Lanoh failed to support this ideology with action. Even as individuals refrained from voicing opposition, concern, or disinterest in community projects, they nonetheless often disregarded and frustrated leaders’ plans or wishes. Unlike for anarchists, however, this failure to accommodate authority stemmed less from a “love of autonomy” and more from prioritizing their need to constantly respond to the calls, pressures, and opportunities of the external world.

Despite their respect for elders, and due to competing commitments to participate in activities outside the community, younger men in Air Bah were unwilling and unable to contribute to the projects these elders attempted to organize. Their individual autonomy and prioritizing last-minute improvised economic ventures undermined larger-scale cooperation for endeavors affecting the whole village as well as tangible support of kinship-group leaders. It was above all their engagement with forest collecting and selling of forest products that pulled Lanoh men away from age-based authority and kinship-based obligations (

Table 1). This summarizes the difference in attitudes toward authority, the source of individual autonomy, and implications for community organization among the shifting cultivators and foragers of Southeast Asia and the anarcho-syndicalists in Spain.

It has been noted that historically, the forager collectors of Peninsular Malaysia had been occupying a unique position—a niche—at the ecotone between swidden cultivators of the interior and agriculturist populations of the coast. As Geoffrey Benjamin has proposed, their social organization likely developed complementary to both their Malay agriculturist and Senoi horticulturist neighbors [

16]. This role implies a strong commitment to a way of life and a pattern of engaging with the broader social environment, a dedication likely derived from the existential significance of collecting. As Porath suggests, “for forest people… the forest was not just a storehouse of food… their relationship with the forest… was as much political as economic” [

35] (p. 135n3). This political relationship with the forest has been generally interpreted in terms of refuge seeking from persecution resulting from encapsulation by outsiders [

29]. It has been indisputably documented that historically the forest collectors of Malaysia suffered from persecution and atrocities. Lanoh still recount tales of Malays taking Orang Asli children to be brought up as

hambas (slaves) of Malay

rajas. Nonetheless, their relationship with agriculturists was far from one sided. A “highly specialized role… in the wider economy of the region” [

9] (p. 228) offered collectors, whether in the forest or at sea, considerable power. As Sather [

9] (p. 230) observes of the Sama Dilaut, “though dependent on trade, by preserving their mobility communities were able to move between rival patrons and so fashion for themselves a notably egalitarian way of life… largely free of outside surveillance and direct state control”. Similarly, whether supplying forest goods or information to agriculturists, forager-collectors performed an important service that allowed them to remain continually relevant to their more dominant neighbors, which ensured their long-term autonomy and cultural as well as physical survival. Not surprisingly, even though it often undermines in-group obligation and loyalties, forest collectors such as Lanoh have prioritized this strategy.

Even today, commitment to collecting is essential to understanding Lanoh responses to various external pressures. This commitment to a forest collecting way of life, for instance, explains in large part why, of all the external pressures put on them by various authorities, Lanoh have resisted religious proselytizers most. “Going along”, instead of directly resisting authority, is a well-recognized strategy of immediate-return hunter-gatherers [

35]. Lanoh similarly refrained from openly opposing external authority, be it the colonial administration, the nation state, or pressure from religious proselytizers. They often stressed the point that they “get along with everyone…”. Nonetheless, people in the village strongly resisted initiatives that threatened to undermine the organizational requirements of forest collecting for trade, such as converting to Islam. This is because adopting an Islamic lifestyle, especially with its strict dietary restrictions, would have interfered with their livelihood, patterns of food choices, and freedom of movement (travelling freely through the forest). Significantly, since hunting facilitates forest collecting of products for exchange, limiting food choices impeded their ability to engage in “forest work”.

This commitment to occupations involving a relationship with outsiders also impacted Lanoh attitudes toward the indigenous political movement. Representatives of POASM, the Orang Asli association of Peninsular Malaysia, had visited Air Bah on at least one occasion to recruit people from the village with very little success. POASM’s oppositional strategy had little appeal to Lanoh, who relied on, and were invested in, social relations with outsiders to a greater extent than the more cohesive and self-contained Senoi swidden cultivators who, at that time, comprised the core of the organization. Despite a concern for land rights and an increasing sense of shared destiny with indigenous peoples in the Peninsula and elsewhere, people in the village were uneasy about alienating mainstream society and refused to join the movement.

Commitment to forest collecting and its organizational requirements also accounts for people’s decisions concerning opportunities to earn money. Above all, this commitment explains why the success of activities that, due to diminishing space and resources, Lanoh are forced to undertake is predicated upon the extent to which these activities harmonize with the organizational requirements of forest collecting for trade. In the past, collecting was mostly conducted by individuals or very small groups. It required little scheduling, allocating roles and responsibilities, or distributing earnings. In addition to rattan, Lanoh used to collect a range of minor forest products such as building materials—bamboo,

atap, and timber—scented wood, honey, spices,

jelutong rubber, resins, frogs, turtles,

petai (bitter bean,

parkia speciosa) and medicine for exchange. Collecting these minor forest products did not promote or stimulate much cooperation among forest collector traders. Irregular demand from villagers and other buyers for forest products encouraged flexibility and discouraged coordinated effort. Individual collectors tended to establish and maintain relationships with villagers and buyers in an ad hoc and opportunistic manner to fulfill intermittent demands. Kaskija’s [

29] (p. 219) account of how relations with outsiders shape Punan social organization also applies to Lanoh. He relates that both Punan communities and individuals had “its own particular constellation of contacts, and its own particular intensity of contact with specific others”.

The social organization of immediate-return hunter-gatherers described by Woodburn [

15] (pp. 437–438, 444) clearly connects to these requirements of interethnic trade (in which Hadza similarly participated). Like Hadza, Lanoh were able to “detach themselves from others at a moment’s notice” which resulted in flexible group and territorial boundaries and hindered people’s ability to move together as a group. These organizational principles ingrained in Lanoh ways of relating to this day place a limit on any larger scale cooperation even when changing circumstances would reward coordination and teamwork. Even though it has been suggested that immediate-return foragers discourage competition [

13,

15], among Lanoh it was imperative not to reveal one’s intentions to others. This implies a degree of competition among collectors and highlights their individualistic relationship with Malay and Chinese villagers [

36]. A similar propensity for secrecy has been observed among foragers elsewhere. As Gardner relates, “despite the general air of friendliness” among Paliyan, when people leave the settlement, others do not know about their plans [

37] (p. 2).

This disinclination on the part of Lanoh to work in groups did not only affect efficiency in farming, but also in contract work. While Lanoh preferred contract work to wage employment since work contracts implied shorter-term commitment, contract engagements nonetheless introduced organizational difficulties. The requirements of rattan collecting today differ greatly from those of collecting forest products in the past. Subcontractors (middlemen, or patrons, “

towkay”) insist on dealing with indigenous collectors as a unit through randomly and opportunistically appointed work leaders. This improvised ad hoc leadership, often based on who happened to “land” the contract, fulfills neither Lanoh expectations of leadership (age, knowledge, charisma, personal and kinship relations) nor past arrangements of forest collecting. Therefore, even though Lanoh still refer to rattan collecting as “forest work”, due to these discrepancies in expectations, it has become a constant source of strife, disagreement, and frustration for Lanoh in their relationship with subcontractors as well as among themselves [

37].

To sum up the argument, contrary to anarchists’ ideological and intentional individualism, Lanoh individualism is underlined by organizational imperatives. It derives from a need for relevance, a need to carve a niche in a specific constellation of inter-group relations, geographic location, and resource distribution. This difference between anarcho-syndicalists’ ideals and Lanoh sociality is captured in two distinct conceptions of anarchy [

38]. According to one, anarchy denotes aspirations for a society without authority. This definition implies “counter-society”, a positive and ideological valuation of freedom from authority and a desire to replace exploitative authoritarian structures with a more just alternative. This conception corresponds to historical and contemporary ideologies of anarchy. According to a second, “everyday”, definition, however, anarchy evokes a disintegration of social order and relations. Arguably, Lanoh sociality resembles the latter conception of anarchy because, instead of a conscious, positive, and ideological valuation of freedom from authority, it implies an unintended weakening of (age) structure—due to the requirements of participating in interethnic trade. In the following, I will consider how this explanation affects long-held assumptions about an egalitarian ethos implied in foragers’ sharing and the “society” debate.