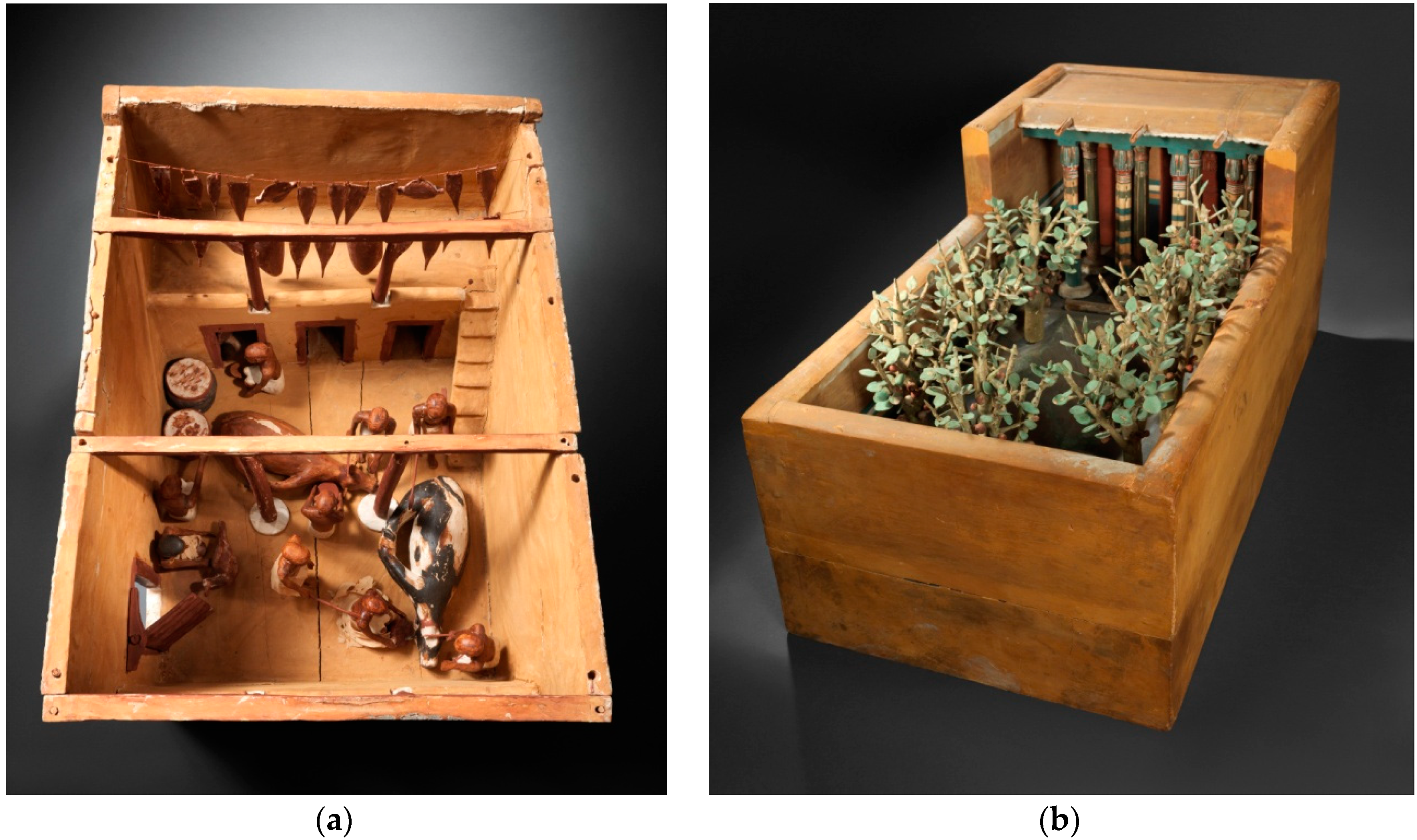

Small WORLD: Ancient Egyptian Architectural Replicas from the Tomb of Meketre

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Clarifications

3.1. Models or Replicas?

3.2. The Internal Point of View

4. From Isolated Active Figurines to Architectural Ensembles

5. Access to an Alternate Dimension

6. Conclusions

- I’m efficient, I’m collected

- My ba is with me

- My heart is in my body

- My corpse in the earth,

- I didn’t weep over it.

- My ba is with me,

- It didn’t go far from me.

- Magic is in my body,

- It wasn’t stolen.

- My akh belongs to me

- My manifestations belong to me

- So that I may eat my meals with my ka who is in this earth of mine,

- So that I may rest, renewed, young again.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The British Museum. Available online: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA35505 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Stadelmann, R. Hausmodelle. In Lexicon der Ägyptologie; Helck, W., Westendorf, W., Eds.; Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1977; Volume 2, pp. 1067–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, H. The Coffin of Heqata (Cairo JdE 36418); Peeters (OLA 70): Leuven, Belgium, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D. Amenemhat I and the Early Twelfth Dynasty at Thebes. MMJ 1991, 26, 5–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.P. Some Theban Officials of the Early Middle Kingdom. In Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson; der Manuelian, P., Ed.; Museum of Fine Arts: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 1, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Brovarski, E. False Doors and History: The First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom. In Archaism and Innovation: Studies in the Culture of Middle Kingdom Egypt; Silverman, D.P., Simpson, W.K., Wegner, J., Eds.; Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 359–425. [Google Scholar]

- Winlock, H.E. Models of Daily Life in Ancient Egypt from the Tomb of Meket-Re’ at Thebes; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (AE 18): Cambridge, MA, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Lepsius, C.R. Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien: Nach den Zeichnungen der von Seiner Majestät dem Könige von Preussen Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Nach Diesen Ländern Gesendeten und in den Jahren 1842–1845; Hinrichs: Leipzig, Germany, 1849; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, P.E. Beni Hasan; Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner: London, UK, 1893; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, N.; Evans, L. The Cemetery of Meir: The Tomb of Pepyankh the Black; Aris and Phillips (ACER 34): Oxford, UK, 2014; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- The Met. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search#!?q=20.3.162 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Legrain, G. Notes sur la nécropole de Meir. ASAE 1900, 1, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, R. The Provincial Cemeteries of Naga ed-Deir: A Comprehensive Study of Tomb Models Dating from the Late Old Kingdom to the Late Middle Kingdom. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7d52746x (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Petrie, W.M.F. Gizeh and Rifeh; School of Archaeology in Egypt, University College, Bernard Quaritch: London, UK, 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Kuentz, C. Bassins et tables d’offrandes. BIFAO 1981, 81, 243–282. [Google Scholar]

- Niwinski, A. Plateaux d’offrandes et “maisons d’âmes”: Genèse, évolution et fonction dans le culte des morts au temps de la XIIe dynastie. ET 1975, 8, 73–122. [Google Scholar]

- Niwinski, A. Seelenhaus (und Opferplatte). In Lexicon der Ägyptologie; Helck, W., Westendorf, W., Eds.; Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1984; Volume 5, pp. 806–813. [Google Scholar]

- Leclère, F. Les “maisons d’âme” égyptiennes: Une tentative de mise au point. In “Maquettes Architecturales” de l’Antiquité: Regards Croisés. Actes du Colloque de Strasbourg, 3–5 Décembre 1998; Muller, B., Ed.; Diffusion De Boccard: Paris, France, 2001; pp. 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, F. Architectural Models of Ancient Egypt: The Soul Houses of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden. In Current Research in Egyptology 2019, Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Symposium, University of Alcalá, Madrid, Spain, 17–21 June 2019; Carcamo, M.A., Casado, R.S., Orozco, A.P., Robledo, S.A., Garcia, J.O., Riudavets, P.M., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, D.W. Prehistoric Figurines: Representation and Corporeality in the Neolithic; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, J. The Art of Small Things; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Davy, J.; Dixon, C. What Makes a Miniature? An Introduction. In Worlds in Minature: Contemplating Miniaturisation in Global Material Culture; Davy, J., Dixon, C., Eds.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Knappett, C. Meaning in Miniature: Semiotic Networks in Material Culture. In Excavating the Mind: Cross Sections through Culture, Cognition and Materiality; Johanssen, N., Jensen, M., Jensen, H.J., Eds.; Aarhus University Press: Aarhus, Denmark, 2012; pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- David, A. Renewing Royal Imagery: Akhenaten and Family in the Amarna Tombs; Brill (HES 11): Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- David, A. The Sound of the Magic Flute in Legal and Religious Registers of the Ramesside Period: Some Common Features of Two “Ritualistic Languages”. In Law and Religion in Eastern Mediterranean; Kratz, R.G., Hagedorn, A.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- David, A. How to Do Things with hw: The Egyptian Performative iw-n-. In Labor Omnia Uicit Improbus: Miscellanea in Honorem Ariel Shisha-Halevy; Bosson, N., Boud’hors, A., Aufrère, S.H., Eds.; Peeters (OLA 256): Leuven, Belgium, 2017; pp. 411–430. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, C. The Savage Mind; Weidenfeld and Nicolson: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Tooley, A.M.J. Middle Kingdom Burial Customs: A Study of Wooden Models and Related Material. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Freed, R.E.; Doxey, D.M. The Djehutynakhts’ Models. In The Secrets of Tomb 10A, Egypt 2000 BC; Freed, R.E., Ed.; MFA Publications: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 151–177. [Google Scholar]

- Tefnin, R. Eléments pour une sémiologie de l’image égyptienne. CdE 1991, 66, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, H. Historical and Archaeological Aspects of Egyptian Funerary Culture: Religious Ideas and Ritual Practice in Middle Kingdom Elite Cemeteries; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Badawy, A. A Monumental Gateway for a Temple of King Sety I: An Ancient Model Restored. Misc. Wilbouriana 1972, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, S. The Use of Model Objects as Predynastic Egyptian Grave Goods: An Ancient Origin for a Dynastic Tradition. In The Archaeology of Death in the Ancient Near East; Campbell, S., Green, A., Eds.; Oxbow Books (OM 51): Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bárta, M. Serdab and Statue Placement in the Private Tombs down to the Fourth Dynasty. MDAIK 1998, 54, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbrenner-Diemer, G. From the Workshop to the Grave: The Case of Wooden Funerary Models. In Company of Images: Modelling the Imaginary World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000–1500 BC), Proceedings of the International Conference of the EPOCHS Project Held UCL, London, UK, 18–20 September 2014; Miniaci, G., Betrò, M., Quirke, S., Eds.; Peeters (OLA 262): Leuven, Belgium, 2017; pp. 133–192. [Google Scholar]

- Breasted, J.H. Egyptian Servant Statues; Pantheon Books (BS 13): Washington, DC, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Eggebrecht, A. Dienerfiguren. In Lexicon der Ägyptologie; Helck, W., Otto, E., Eds.; Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1975; Volume 1, pp. 1080–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, A.M. The Meaning of Menial Labor: “Servant Statues” in Old Kingdom Serdabs. JARCE 2002, 39, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolshakov, A.O. Man and his Double in Egyptian Ideology of the Old Kingdom; Harrassowitz (ÄAT 37): Wiesbaden, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood, K. Animate Decoration and Burial Chambers of Private Tombs during the Old Kingdom: New Evidence from the Tomb of Kairer at Saqqara. In Des Néferkarê aux Montouhotep: Travaux Archéologiques en Cours sur la Fin de la VIe Dynastie et la Première Période Intermédiaire. Actes du Colloque CNRS–Université Lumière Lyon 2, Lyon, France, 5–7 July 2001; Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux (TMOM 40): Lyon, France, 2005; pp. 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, N. Decoration of the Burial Chambers, Sarcophagi and Coffins in the Old Kingdom. In Studies in Honor of Ali Radwan; Daoud, K., Bedier, S., Abd el-Fatah, S., Eds.; Conseil Supreme des Antiquités de l’Égypte (ASAE-Suppl. 34): Cairo, Egypt, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lashien, M. The Ultimate Destination: Decoration of Kaiemankh’s Burial Chamber Reconsidered. ET 2013, 26, 404–415. [Google Scholar]

- Bourriau, J. Patterns of Change in Burial Customs during the Middle Kingdom. In Middle Kingdom Studies; Quirke, S., Ed.; SIA Publishing: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, A. Introduction: What Was the Middle Kingdom? In Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom; Oppenheim, A., Arnold, D., Arnold, D., Yamamoto, K., Eds.; The Metropolitan Musuem of Art: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tooley, A.M.J. Egyptian Models and Scenes; Shire Publications (SES 2): Princes Risborough, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbrenner-Diemer, G.; Russo, B. Quelques particuliers inhumés à Saqqâra Nord au début du Moyen Empire. BIFAO 2014, 114, 155–186. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen-Frankfort, H.A. Arrest and Movement: An. Essay on Space and Time in the Representational Art of the Ancient Near East; Faber and Faber Limited: London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Angenot, V. La formule mAA (“regarder”) dans les tombes privées de la dix-huitième dynastie. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Bruxelles, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Quibell, J.E.; Hayter, A.G.K. Excavations at Saqqara-Teti Pyramid, North Side; Imprimerie de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale: Cairo, Egypt, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Passalacqua, J. Catalogue Raisonné et Historique des Antiquités en Égypte; Imprimerie de C. J. Trouvé: Paris, France, 1826. [Google Scholar]

- Žabkar, L. A Study of the Ba Concept in Ancient Egyptian Texts; The University of Chicago Press (SAOC 34): Chicago, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Englund, G. Akh: Une Notion Religieuse Dans l’Égypte Pharaonique; Almqvist & Wiksell International (BOREAS 11): Uppsala, Sweden, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.P. Ba. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt; Redford, D.B., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; Volume 1, pp. 161–162. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, J. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nyord, R. Seeing Perfection: Ancient Egyptian Images beyond Representation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Janák, J. Ba. In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology; Dieleman, J., Wendrich, W., Eds.; UCLA Library: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002k7g85 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Donnat, S. Le Dialogue d’un homme avec son ba à la lumière de la formule 38 des Textes des Sarcophages. BIFAO 2004, 104, 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- de Buck, A. The Egyptian Coffin Texts; The University of Chicago Press (OIP 64): Chicago, IL, USA, 1947; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Devéria, T. Le Papyrus de Neb-Qed (Exemplaire Hiéroglyphique du Livre des Morts); A. Franck: Paris, France, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, H. Sein Ba möge fortdauern bei Gott. SAK 1993, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer, M. An Isolated Middle Kingdom Tomb at Dayr al-Barsha. In The World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000-1550 BC): Contributions on Archaeology, Art, Religion, and Written Sources, Miniaci, G., Grajetzki, W., Eds.; Golden House Publications (MKS 2): London, UK, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 85–115. [Google Scholar]

- de Buck, A. The Egyptian Coffin Texts; The University of Chicago Press (OIP 34): Chicago, IL, USA, 1947; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- de Buck, A. The Egyptian Coffin Texts; The University of Chicago Press (OIP 87): Chicago, IL, USA, 1961; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- de Buck, A. The Egyptian Coffin Texts; The University of Chicago Press (OIP 49): Chicago, IL, USA, 1938; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- de Buck, A. The Egyptian Coffin Texts; The University of Chicago Press (OIP 81): Chicago, IL, USA, 1956; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- de Buck, A. The Egyptian Coffin Texts; The University of Chicago Press (OIP 67): Chicago, IL, USA, 1951; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kamrin, J. The Cosmos of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan; Kegan Paul International: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Superstructure | Substructure |

|---|---|

| Open | Closed |

| World of the ka | World of the corpse, ba, and other manifestations |

| Cult of the ka—the deceased is served by the cult | No cult after burial—the deceased is served by his ba and other manifestations |

| Performative images (murals, deceased statue) | Performative images (replicas, rare murals, deceased statue) |

| The deceased contemplates 2D activities performed for his benefit and accesses the offerings through the false door | The deceased statue/mummy contemplates and the ba accesses 3D replicas through their doors |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

David, A. Small WORLD: Ancient Egyptian Architectural Replicas from the Tomb of Meketre. Humans 2021, 1, 18-28. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans1010004

David A. Small WORLD: Ancient Egyptian Architectural Replicas from the Tomb of Meketre. Humans. 2021; 1(1):18-28. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans1010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavid, Arlette. 2021. "Small WORLD: Ancient Egyptian Architectural Replicas from the Tomb of Meketre" Humans 1, no. 1: 18-28. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans1010004

APA StyleDavid, A. (2021). Small WORLD: Ancient Egyptian Architectural Replicas from the Tomb of Meketre. Humans, 1(1), 18-28. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans1010004