Assessment of the Use of Coconut Water as a Cultivation Medium for Limnospira (Arthrospira) platensis (Gomont): Effects on Productivity and Phycocyanin Concentration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculum Preparation, Culture Media and Experimental Design

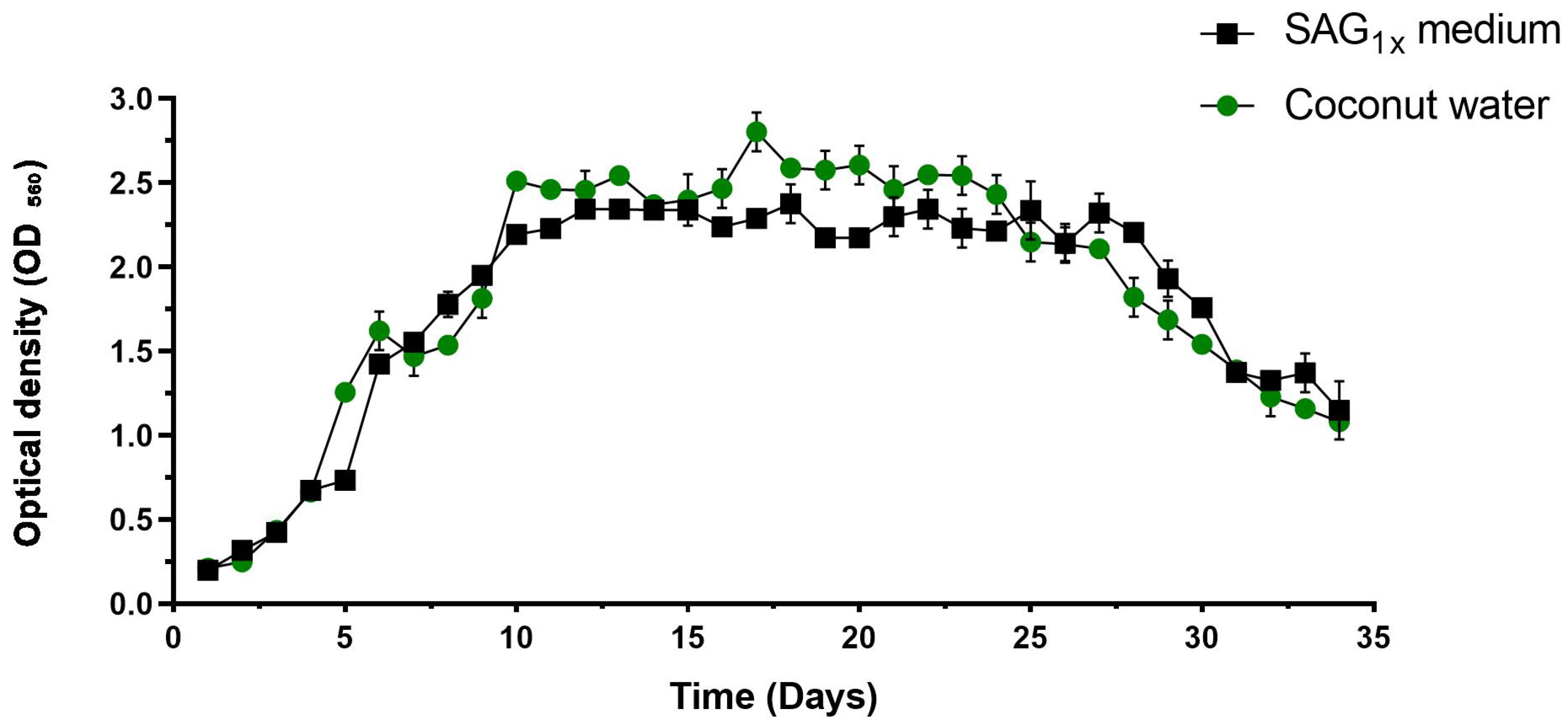

2.2. Growth Parameters

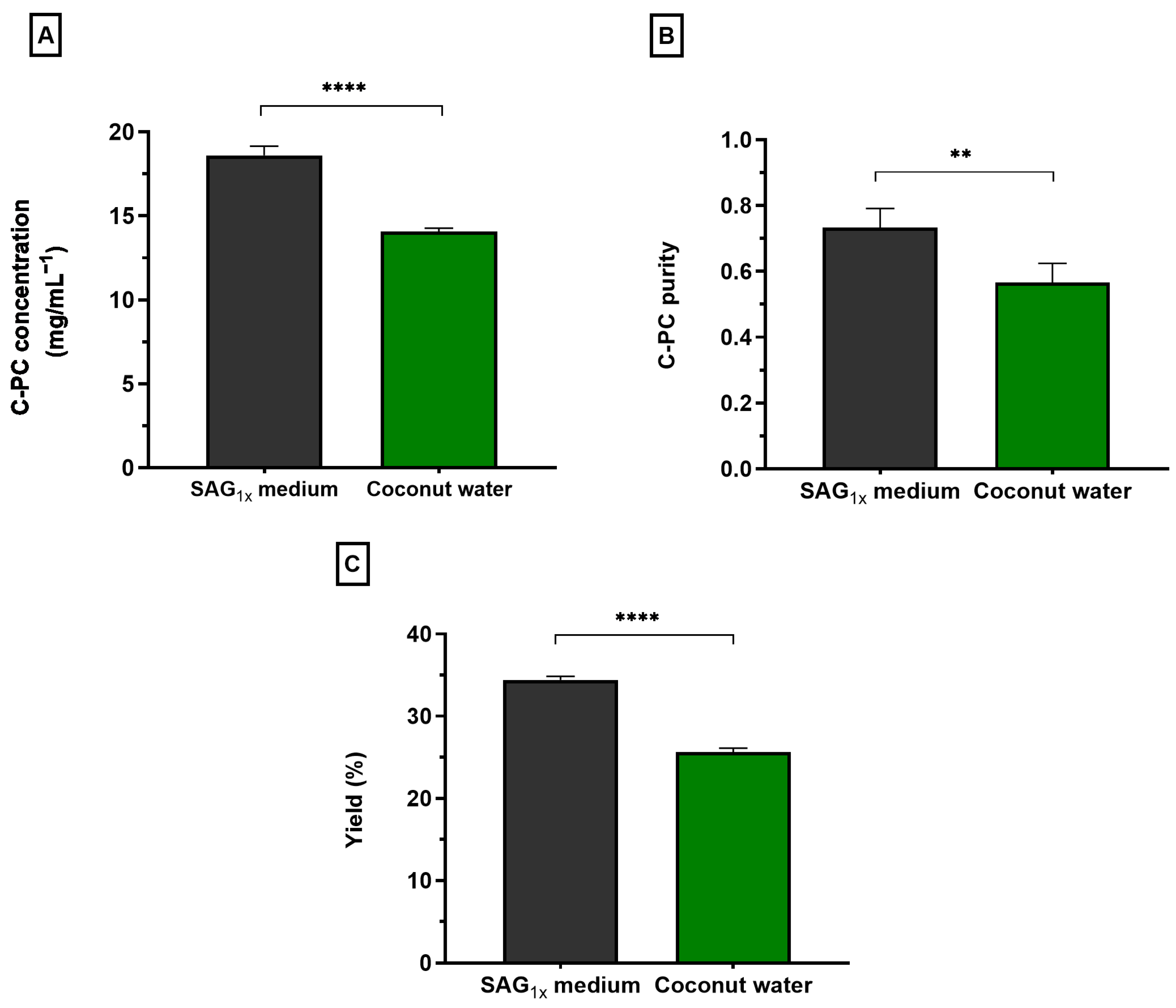

2.3. Pigment Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CF | Phycocyanin concentration |

| C-PC | C-phycocyanin |

| OD | Optical Density |

| PE | Phycocyanin purity |

| Px | Cell productivity |

| R | Yield |

| SAG | Sammlung von Algenkulturen Göttingen |

| SAG1x | Spirulina 1x modified medium |

| UTEX | The Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Texas at Austin |

| μ | Specific growth rate |

| μmax | Maximum growth rate |

References

- Militão, F.P.; Fernandes, V.d.O.; Bastos, K.V.; Martins, A.P.; Colepicolo, P.; Machado, L.P. Nutritional value changes in response to temperature, microalgae mono and mixed cultures. Acta Limnol. Bras. 2019, 31, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomón, S.; Rivera-Rondón, C.A.; Zapata, Á.M.; Salomón, S.; Rivera-Rondón, C.A.; Zapata, Á.M. Floraciones de cianobacterias en Colombia: Estado del conocimiento y necesidades de investigación ante el cambio global. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Exactas Físicas Nat. 2020, 44, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demay, J.; Bernard, C.; Reinhardt, A.; Marie, B. Natural products from cyanobacteria: Focus on beneficial activities. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tao, H.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, B. Secondary metabolites from cyanobacteria: Source, chemistry, bioactivities, biosynthesis and total synthesis. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 483–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlgaeBase. Limnospira Platensis (Gomont) KRSSantos & Hentschke: AlgaeBase. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=194031 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Maag, P.; Dirr, S.; Karslioglu, Ö.Ö. Investigation of bioavailability and food-processing properties of Arthrospira platensis by enzymatic treatment and micro-encapsulation by spray drying. Foods 2022, 11, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazi, M.I.; Demirel, Z.; Dalay, M.C. Evaluation of growth and phycobiliprotein composition of cyanobacteria isolates cultivated in different nitrogen sources. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, N.T. Production of phycocyanin-A pigment with applications in biology, biotechnology, foods and medicine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M.R.O.B.; da Silva, G.M.; Silva, A.L.F.D.; Lima, L.R.A.D.; Bezerra, R.P.; Marques, D.D.A.V. Bioactive compounds of Arthrospira Spp. (Spirulina) with potential anticancer activities: A systematic review. ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 2057–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braune, S.; Krüger-Genge, A.; Kammerer, S.; Jung, F.; Küpper, J.H. Phycocyanin from Arthrospira platensis as potential anti-cancer drug: Review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Life 2021, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwil, M.; Mihelič, R.; Matraszek-Gawron, R.; Terlecka, P.; Skoczylas, M.M.; Terlecki, K. Comprehensive review of the latest investigations of the health-enhancing effects of selected properties of Arthrospira and Spirulina microalgae on skin. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, S.C. The potential of Arthrospira platensis extract as a tyrosinase inhibitor for pharmaceutical or cosmetic applications. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 119, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setthamongkol, P.; Kulert, W.; Wanmanee, S.; Swami, R.; Kutako, M.; Chanthathamrongsiri, N.; Semangoen, T.; Hiransuchalert, R. In vitro characterization and assessment of a potential cosmetic cream containing phycocyanin extracted from Arthrospira platensis BUUC1503 blue-green algae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 1685–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Dhar, D.W.; Pabbi, S.; Kumar, N.; Walia, S. Extraction and purification of C-phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis (CCC540). Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 19, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). HHS, FDA to Phase out Petroleum-Based Synthetic Dyes in Nation’s Food Supply. Brown Univ. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. Update 2025, 27, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, D.; Alcides Brandini, L. The revolution in American Public Health Policy: Petroleum-based dyes and the chronic disease epidemic. Forum Artic. South. J. Sci. 1993, 33, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Athiyappan, K.D.; Routray, W.; Paramasivan, B. Phycocyanin from Spirulina: A comprehensive review on cultivation, extraction, purification, and its application in food and allied industries. Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiklahan, R.; Chirasuwan, N.; Srinorasing, T.; Attasat, S.; Nopharatana, A.; Bunnag, B. Enhanced biomass and phycocyanin production of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis by a cultivation management strategy: Light intensity and cell concentration. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejsungkranont, M.; Chisti, Y.; Sirisansaneeyakul, S. Optimization of production of C-phycocyanin and extracellular polymeric substances by Arthrospira Sp. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 40, 1173–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.M.; Kumar, K.; Das, D. Physicochemical parameters optimization, and purification of phycobiliproteins from the isolated Nostoc Sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 166, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M.S.H.; Halim, M.; Wong, F.W.F.; Wasoh, H.; TAN, J.S.; Mohamed, M.S. Enhancing the production of phycocyanin biopigment from microalga Arthrospira maxima through medium manipulation utilizing box-behnken design. Nusant. Biosci. 2024, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogany, T.; Swalaha, F.M.; Kumari, S.; Bux, F. Elucidating the role of nutrients in C-phycocyanin production by the halophilic cyanobacterium Euhalothece Sp. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2259–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyoningrum, T.M.; Nur, M.M.A. Optimization of C-phycocyanin production from S. platensis cultivated on mixotrophic condition by using response surface methodology. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2015, 4, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, Y. High cell density mixotrophic culture of Spirulina platensis on glucose for phycocyanin production using a fed-batch system. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1997, 20, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hu, H.; Wu, X.; Wang, C.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, R.; Zheng, H. Continuous cultivation of Arthrospira platensis for phycocyanin production in large-scale outdoor raceway ponds using microfiltered culture medium. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 287, 121420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.; Pereira, H.; Costa, M.; Santos, T.; Carvalho, B.; Soares, M.; Quelhas, P.; Silva, J.T.; Trovão, M.; Barros, A.; et al. Development of an organic culture medium for autotrophic production of Chlorella vulgaris biomass. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.K.; Lee, W.K.; Choi, W.Y.; Kim, T.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, A.; Park, H.S.; Oh, C.; Kang, D.H. Potential of a chicken manure concentrate additive for Arthrospira maxima (Cyanophyceae): Biochemical characterization and phycocyanin production. Phycologia 2024, 63, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusydi, R.; Ayuzar, E.; Muliani, M.; Saifuddin, S. A comprehensive study of potential Arthrospira platensis cultivated in various manure-based media for biodiesel feedstock. Indones. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 29, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineshkumar, R.; Umamageswari, P.; Jayasingam, P.; Sampathkumar, P. Enhance the growth of Spirulina platensis using molasses as organic additives. World J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 4, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Shayanthavi, S.; Kapilan, R.; Wickramasinghe, I. A Comprehensive review of coconut liquid endosperm (Cocos nucifera L.): Composition, physicochemical characteristics, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, and applications in microbial and tissue culture media. J. Sci. Univ. Kelaniya 2025, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, N.; Veetil, S.K.; Neerathilingam, M. Tender Coconut water an economical growth medium for the production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. BMC Biotechnol. 2013, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.S.; Rosa, Y.B.C.J.; Suzuki, R.M.; Scalon, S.P.Q.; Rosa Junior, E.J. Cultivo in vitro de Dendrobium nobile com uso de água de coco no meio de cultura. Hortic. Bras. 2013, 31, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadcharoen, A.; Cheirsilp, B.; Ruangwicha, J.; Srinuanpan, S.; O Thong, S. Utilization of agro-industrial byproducts as low-cost nutrient sources for production of kefiran and lactic acid by Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2025, 8, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.Q.E.; Haradzi, N.A.; Sriskanda, D.; Subramaniam, S.; Chew, B.L. Effects of Coconut water and banana homogenate on shoot regeneration of meyer lemon (Citrus × Meyeri). Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. Sci. 2024, 47, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, M.A.; Diniz, S.; Danielli, S.; De, M.; Dantas, M.; Olivera Gálvez, A. Algas Cultiváveis e Sua Aplicação Biotecnológica; 1a Edição Instituto Federal; Instituto Federal de Sergipe: Aracaju, SE, Brazil, 2016; pp. 1–98. ISBN 978-85-68801-37-6. [Google Scholar]

- de Queiroz Andrade, H.M.M.; Rosa, L.P.; de Souza, F.E.S.; da Silva, N.F.; Cabral, M.C.; Alves Teixeira, D.I. Seaweed Production potential in the Brazilian Northeast: A Study on the Eastern coast of the state of Rio Grande do Norte, RN, Brazil. Sustainability 2020, 12, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Almeida, A.P.; de Albuquerque, T.L. Coconut Husk Valorization: Innovations in bioproducts and environmental sustainability. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 13015–13035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimatun Nur, M.M.; Irawan, M.A. Hadiyanto Utilization of coconut milk skim effluent (CMSE) as medium growth for Spirulina platensis. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 23, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukanya, A.; Meena, R.; Ravindran, A.D. Cultivation of Spirulina using low-cost organic medium and preparation of phycocyanin based ice creams. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.N.; Jirgi, G.M.; Zango, Z.U.; Isah, M.N.; Abdurrazak, M.; Adamu, A.A.; Wadi, I.A.; Adeleke, A.A.; Garba, Z.N.; Bello, U.; et al. A Review on techno-economic assessment of Spirulina for sustainable nutraceutical, medicinal, environmental, and bioenergy applications. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UTEX Spirulina Medium|UTEX Culture Collection of Algae. Available online: https://utex.org/products/spirulina-medium?utm_source=chatgpt.com&variant=30991737454682 (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Duan, Y.; Guo, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y. Nutrients recycle and the growth of Scenedesmus obliquus in synthetic wastewater under different sodium carbonate concentrations. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.W.H.; Ge, L.; Ng, Y.F.; Tan, S.N. The chemical composition and biological properties of coconut (Cocos Nucifera L.) water. Molecules 2009, 14, 5144–5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchoubassi, G.; Kińska, K.; Bierla, K.; Lobinski, R.; Szpunar, J. Speciation of essential nutrient trace elements in coconut water. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prades, A.; Dornier, M.; Diop, N.; Pain, J.P. Coconut water uses, composition and properties: A review. Fruits 2012, 67, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Bogobad, L. Complementary chromatic adaptation in a filamentous blue-green alga. J. Cell Biol. 1973, 58, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antelo, F.S.; Anschau, A.; Costa, J.A.V.; Kalil, S.J. Extraction and purification of C-phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis in conventional and integrated aqueous two-phase systems. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2010, 21, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.T.; Burkert, J.F.M.; Costa, J.A.V.; Burkert, C.A.V.; Kalil, S.J. Optimization of phycocyanin extraction from Spirulina platensis using factorial design. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, J.A.V.; Freitas, B.C.B.; Rosa, G.M.; Moraes, L.; Morais, M.G.; Mitchell, B.G. Operational and economic aspects of Spirulina-based biorefinery. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 121946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaza, J.A.; Hossain, M.S.; Meiler, K.A.; Velasquez, S.F.; Kumar, V. A review on Spirulina: Alternative media for cultivation and nutritive value as an aquafeed. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2371–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, Y.; Rodrigues, S.; Dos, E.; Almeida, S.; Vieira, E.D. Characterization of Arthrospira sp. (Spirulina) biomass growth in hydroponic waste solution: A Review. J. Bioeng. Technol. Health 2020, 3, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.; Yang, P.; Yang, H.; He, X.; Liao, X. Research progress in coconut water: A review of nutritional composition, biological activities, and novel processing technologies. Foods 2025, 14, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, H.A. Market potential of pasteurized coconut water in the Philippine beverage industry. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2017, 7, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thathsatani, A.O.T.; Arunakumara, K.K.I.U.; Marikar, F.M.M.T. Development of low-cost growing media with mungbean as a source of carbon for Spirulina. Peruv. J. Agron. 2023, 7, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, S.; Hossain, M.; Akter, T.; Banu, M.; Kawser, A. Replacement of sodium bicarbonate and micronutrients in Kosaric medium with Banana Leaf ash extract for culture of Spirulina platensis. Ann. Bangladesh Agric. 2020, 23, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Ahmed, M.; Sarker, N.; Mahbub, R.; Abdul, M.; Sarker, M. Growth response of Spirulina platensis in Papaya skin extract and antimicrobial activities of Spirulina extracts in different culture media. Bangladesh J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2012, 47, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasena, A.; Nurrachmi, I.; Zulkifli, Z. Effect of addition of coconut water as enrichment of Spirulina platensis growth media in laboratory scale. Asian J. Aquat. Sci. 2023, 6, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiyah, R.; Muliani, M.; Mahdaliana, M.; Rusydi, R.; Mainisa, M. Application of liquid organic fertilizer from wild banana stem waste (Musa Acuminate) and coconut husk as a culture medium for Spirulina platensis. Acta Aquat. Aquat. Sci. J. 2023, 10, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, E.; Cascino, F.C.; Foglio, L.; Proietti, L.; Perteghella, S.; Torre, M.L.; Parati, K. Alternative culture media and cold-drying for obtaining high biological value Arthrospira platensis (Cyanobacteria). Phycologia 2021, 60, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarko, T.; Duda-Chodak, A.; Kobus, M. Influence of growth medium composition on synthesis of bioactive compounds and antioxidant properties of selected strains of Arthrospira Cyanobacteria. Czech J. Food Sci. 2012, 30, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balseca, F.; Reyes, C.; Rodríguez, M.; Veselova, V.; Maksimov, I.; Alberto Freire Balseca, D.; Susana Castro Reyes, K.; Elena Maldonado Rodríguez, M. Optimization of an alternative culture medium for phycocyanin production from Arthrospira platensis under laboratory conditions. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Diamantis, A.; Arapoglou, D.; Mitrogiannis, D.; González-Fernández, C.; Unc, A. Growing Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) in seawater supplemented with digestate: Trade-Offs between increased salinity, nutrient and light availability. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 165, 107815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, L.; Vu, H.P.; Abu Hasan Johir, M.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Silitonga, A.S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Tra, V.T.; Ngo, H.H.; Nghiem, L.D. Role of culture solution PH in balancing CO2 input and light intensity for maximising microalgae growth rate. Chemosphere 2023, 343, 140255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kulshreshtha, J.; Singh, G.P. Growth and biopigment accumulation of cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis at different light intensities and temperature. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2011, 42, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.; Kyewalyanga, M.S.; Lugomela, C.V. Biomass and nutritive value of Spirulina (Arthrospira fusiformis) cultivated in a cost-effective medium. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.R.; Costa, J.A.V. Mixotrophic cultivation of microalga Spirulina platensis using molasses as organic substrate. Aquaculture 2007, 264, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkour, F.F.; Kamil, A.E.W.; Nasr, H.S. Production and nutritive value of Spirulina platensis in reduced cost media. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2012, 38, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufikurahman, T.; Ilhamsyah, D.P.A.; Rosanti, S.; Ardiansyah, M.A. Preliminary design of phycocyanin production from Spirulina platensis using anaerobically digested dairy manure wastewater. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 520, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.I.B.; Chagas, B.M.E.; Sassi, R.; Medeiros, G.F.; Aguiar, E.M.; Borba, L.H.F.; Silva, E.P.E.; Neto, J.C.A.; Rangel, A.H.N. Mixotrophic cultivation of Spirulina platensis in dairy wastewater: Effects on the production of biomass, biochemical composition and antioxidant capacity. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonshak, A.; Cheung, S.M.; Chen, F. Mixotrophic growth modifies the response of Spirulina (Arthrospira) platensis (Cyanobacteria) cells to light. J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.W.; Zhang, Y.M.; Chen, F. Application of mathematical models to the determination optimal glucose concentration and light intensity for mixotrophic culture of Spirulina platensis. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, J.C.A.; Balbinot, L.; Beuter, M.A.; Rempel, A.; Colla, L.M. Mixotrophic cultivation of microalgae using agro-industrial waste: Tolerance level, scale up, perspectives and future use of biomass. Algal Res. 2024, 80, 103554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohoiulun, D.; Endang, Y.H.; Mahmudi, M. The effect of with coconut water content on different concentration of essential Chlorella pyronoidosa chick international journal of biosciences. Int. J. Biosci. 2014, 5, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, W.R.; da Silva, M.L.; Tagliaferro, G.V.; Ferreira, A.L.G.; Guimarães, D.H.P. The cultivation of Spirulina maxima in a medium supplemented with leachate for the production of biocompounds: Phycocyanin, carbohydrates, and biochar. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A.P.; Nogueira, A.O.d.M.; Salgado, H.Z.; Kokuszi, L.T.F.; Costa, J.A.V.; de Lima, V.R.; Santos, L.O. Simultaneous application of mixotrophic culture and magnetic fields as a strategy to improve Spirulina Sp. LEB 18 Phycocyanin synthesis. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 4014–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rito-Palomares, M.; Nuez, L.; Amador, D. Practical application of aqueous two-phase systems for the development of a prototype process for C-phycocyanin recovery from Spirulina maxima. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2001, 76, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, G.; Chethana, S.; Sridevi, A.S.; Raghavarao, K.S.M.S. Method to obtain C-phycocyanin of high purity. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1127, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemicals/Compounds | Concentration in SAG1x Medium (g L−1) | Concentration Naturally Present in Coconut Water (g L−1) | Supplemented in Coconut Water? (g L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaHCO3 | 27.22 | n.d. | No |

| Na2CO3 | 8.06 | n.d. | Yes (for pH adjustment) |

| K2HPO4 | 1 | 0.027–0.033 | No |

| NaNO3 | 5 | 0.0002–0.0010 (traces) | No |

| K2SO4 | 2 | 0.02–0.062 | No |

| NaCl | 2 | 0.40–1.20 | No |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 0.4 | 0.10–0.12 | No |

| CaCl2·2H2O | 0.08 | 0.074–0.185 | No |

| Vitamin B12 | 2 mL | n.d. | No |

| P-IV Metal Solution | 12 mL | - | - |

| Composition of Metal Solution | |||

| Na2EDTA·2H2O | 0.75 | n.d. | Yes—0.75 |

| FeCl3·6H2O | 0.097 | 0.0001–0.0005 (traces) | Yes—0.097 |

| MnCl2·4H2O | 0.041 | 0.00002–0.0001 (traces) | Yes—0.041 |

| ZnCl2 | 0.005 | 0.00001–0.00006 (traces) | Yes—0.005 |

| CoCl2·6H2O | 0.002 | <0.000001 (traces) | Yes—0.002 |

| Na2MoO4·2H2O | 0.004 | <0.000001 (traces) | Yes—0.004 |

| Chu Micronutrient Solution | 2 mL | - | - |

| Composition of Micronutrient Solution | |||

| CuSO4·5H2O | 0.02 | 0.00002–0.00005 (traces) | Yes—0.02 |

| ZnSO4·7H2O | 0.044 | 0.00001–0.00006 (traces) | Yes—0.044 |

| CoCl2·6H2O | 0.02 | <0.000001 (traces) | Yes—0.02 |

| MnCl2·4H2O | 0.012 | 0.00002–0.0001 (traces) | Yes—0.012 |

| Na2MoO4·2H2O | 0.012 | n.d. | Yes—0.012 |

| H3BO3 | 0.62 | 0.005–0.009 | Yes—0.062 |

| Na2EDTA·2H2O | 0.05 | n.d. | Yes—0.05 |

| Growth Parameter | SAG1x Medium | Coconut Water | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific growth rate (μ) | 0.240 ± 0.024 d−1 | 0.305 ± 0.023 d−1 | 0.0043 * |

| Maximum growth rate (μmax) | 0.676 ± 0.0034 d−1 | 0.629 ± 0.0019 d−1 | 0.0022 * |

| Productivity (Px) | 0.218 ± 0.0019 g L−1·d−1 | 0.256 ± 0.0019 g L−1·d−1 | 0.0022 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Silva, M.R.O.B.; do Nascimento, B.E.G.; Mendes, M.E.M.; da Silva, R.O.B.; da Silva, S.d.F.F.; Costa, R.M.P.B.; Viana Marques, D.d.A. Assessment of the Use of Coconut Water as a Cultivation Medium for Limnospira (Arthrospira) platensis (Gomont): Effects on Productivity and Phycocyanin Concentration. Phycology 2025, 5, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040082

da Silva MROB, do Nascimento BEG, Mendes MEM, da Silva ROB, da Silva SdFF, Costa RMPB, Viana Marques DdA. Assessment of the Use of Coconut Water as a Cultivation Medium for Limnospira (Arthrospira) platensis (Gomont): Effects on Productivity and Phycocyanin Concentration. Phycology. 2025; 5(4):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040082

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Silva, Maria Rafaele Oliveira Bezerra, Bruna Emanuelle Gomes do Nascimento, Maria Eduarda Moura Mendes, Rayane Oliveira Bezerra da Silva, Silvana de Fátima Ferreira da Silva, Romero Marcos Pedrosa Brandão Costa, and Daniela de Araújo Viana Marques. 2025. "Assessment of the Use of Coconut Water as a Cultivation Medium for Limnospira (Arthrospira) platensis (Gomont): Effects on Productivity and Phycocyanin Concentration" Phycology 5, no. 4: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040082

APA Styleda Silva, M. R. O. B., do Nascimento, B. E. G., Mendes, M. E. M., da Silva, R. O. B., da Silva, S. d. F. F., Costa, R. M. P. B., & Viana Marques, D. d. A. (2025). Assessment of the Use of Coconut Water as a Cultivation Medium for Limnospira (Arthrospira) platensis (Gomont): Effects on Productivity and Phycocyanin Concentration. Phycology, 5(4), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040082