In Nulliparous and Multiparous Ovariectomized Goats Is Possible to Induce Maternal Behavior with Hormonal Treatment Plus Vagino-Cervical Stimulation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Feeding and Maintenance Conditions

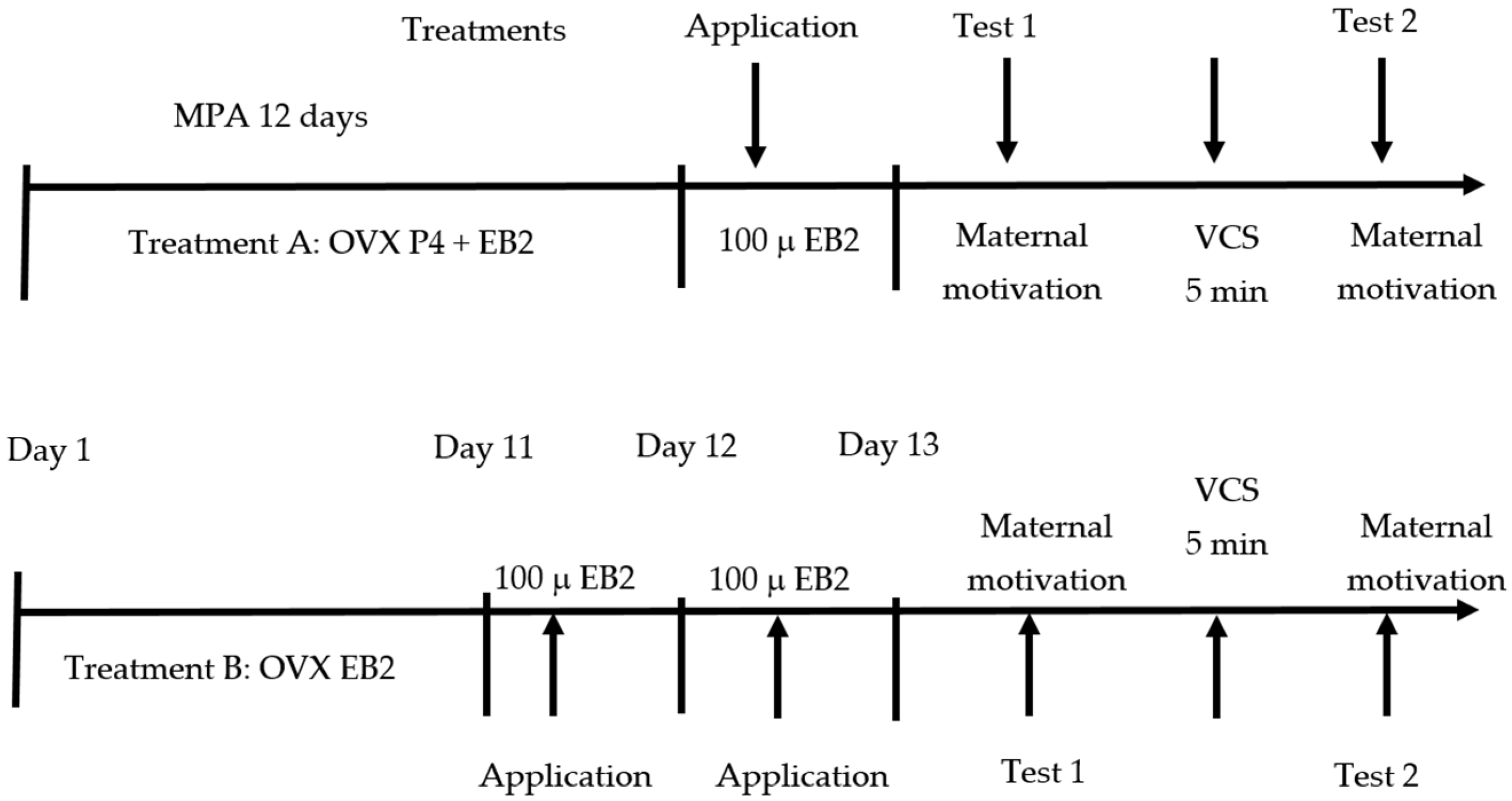

2.2. Experimental Process

2.2.1. Ovariectomies

2.2.2. Experimental Groups

- (1)

- In the estradiol only group (EB2), ovariectomized goats (7 nulliparous and 10 multiparous goats) were given 2 intramuscular injections of estradiol benzoate with 24 h intervals between each application (100 μ per injection/day, Lab. Syntex, Mexico City, Mexico) over 48 h.

- (2)

- In the progesterone + estradiol (P4 + EB2) group, ovariectomized goats (7 nulliparous and 7 multiparous goats) were treated with intravaginal sponges (for 11 days) with a progestogen known as cronolone (20 mg; Chronogest CR®, Intervet Productions S. A., Igoville, France). A single dose of 100 μg of EB2 was injected intramuscularly, 12 h after sponge removal.

2.2.3. Parturition and Birth of Offspring for Maternal Motivation Tests

2.2.4. Maternal Motivation Tests on Ovariectomized Goats with Hormone Treatment

Maternal Motivation Test Before Vagino-Cervical Stimulation (VCS)

Maternal Motivation Test After Vagino-Cervical Stimulation

2.2.5. Maternal Motivation Index

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

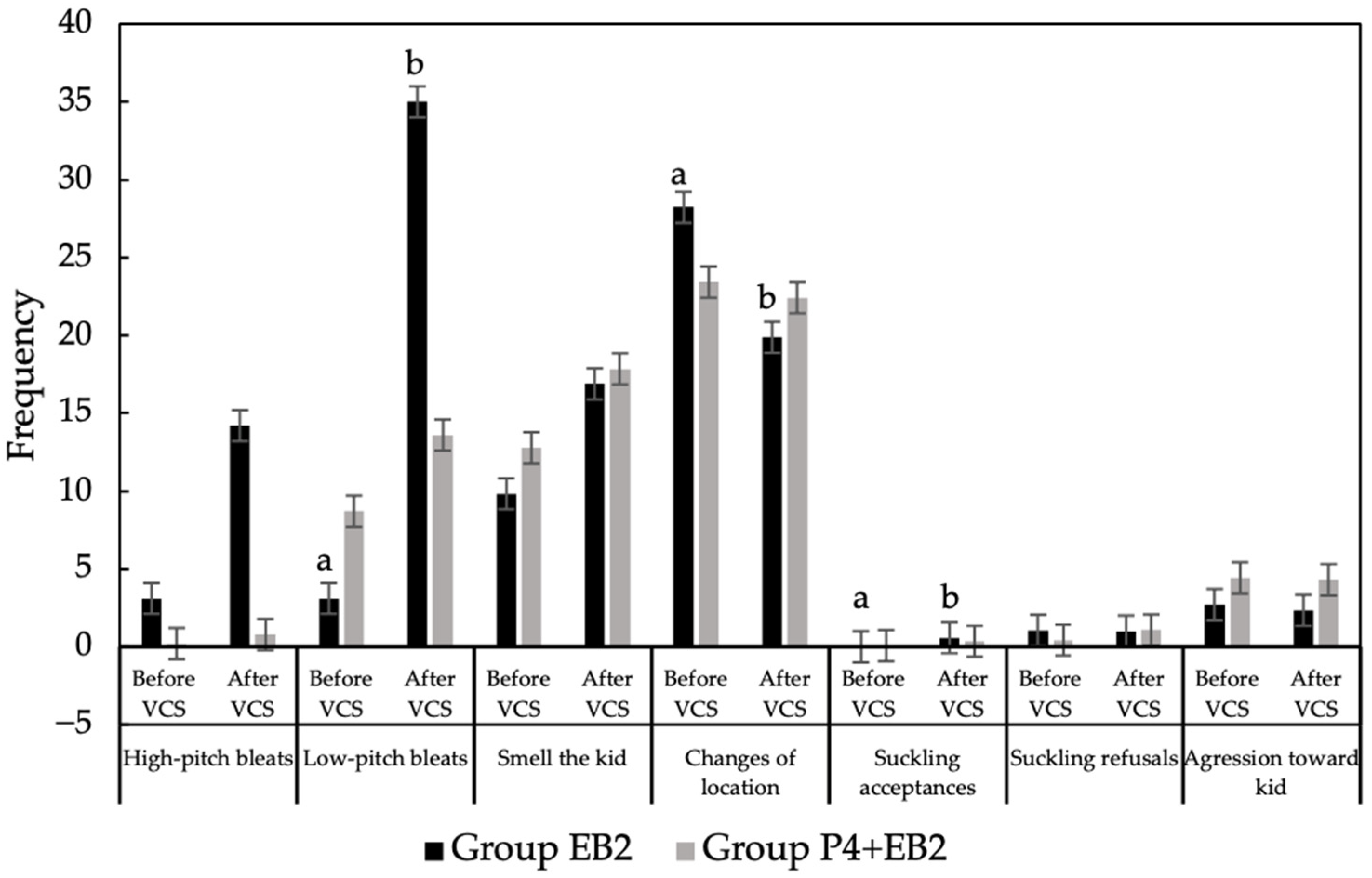

3.1. Tests of Maternal Motivation Compared Between Treatments Without Considering Parity

3.2. Tests of Maternal Motivation Compared Within Treatments Without Considering Parity

3.3. Comparison Between Treatments in the Maternal Motivation Test in Nulliparous Goats

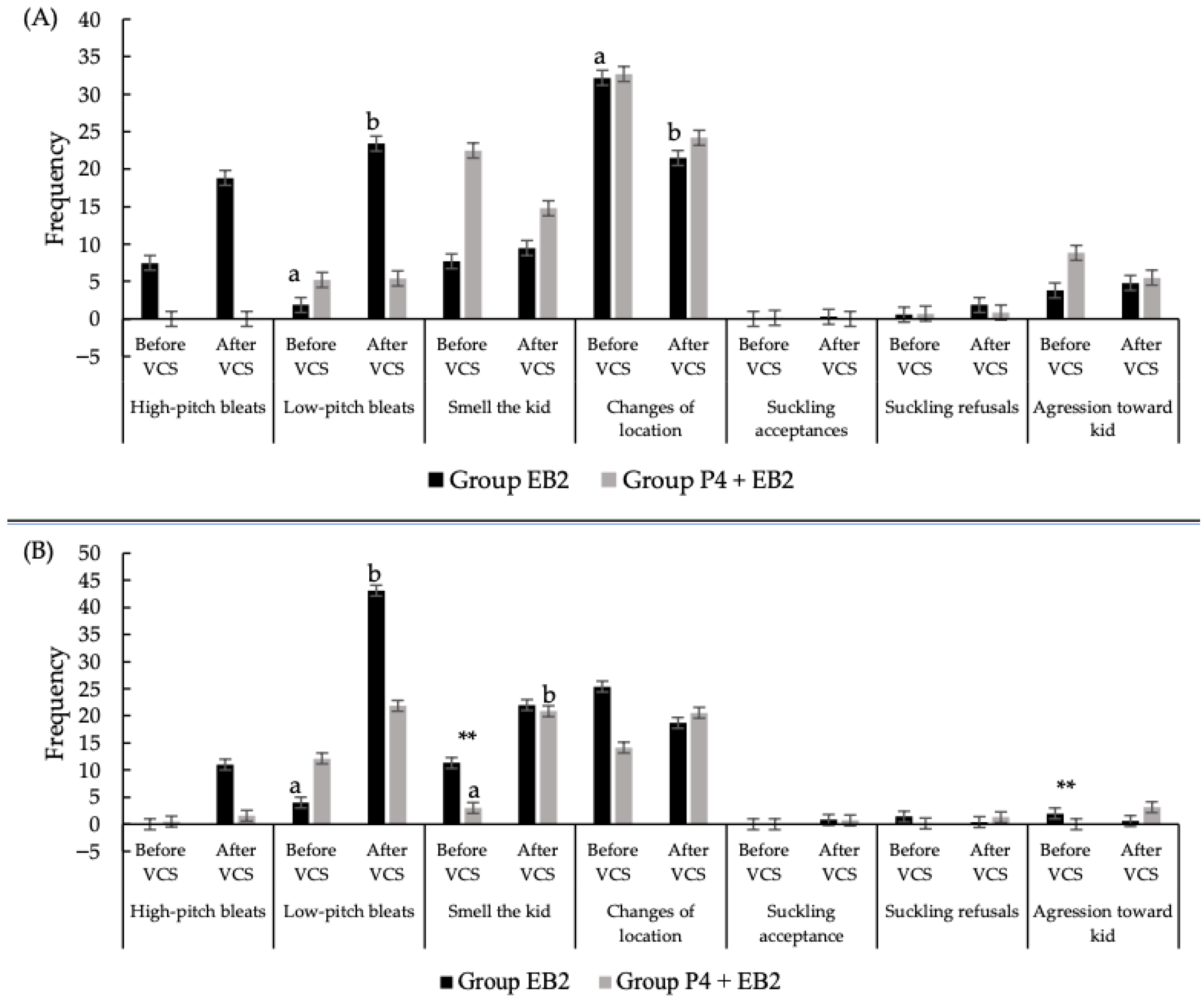

3.4. Comparison Within Treatments in the Maternal Motivation Test in Nulliparous Goats

3.5. Comparison Between Treatments in the Maternal Motivation Test in Multiparous Goats

3.6. Comparison Within Treatments in the Maternal Motivation Test in Multiparous Goats

3.7. Maternal Index Comparing Within Treatments Without Considering Parity

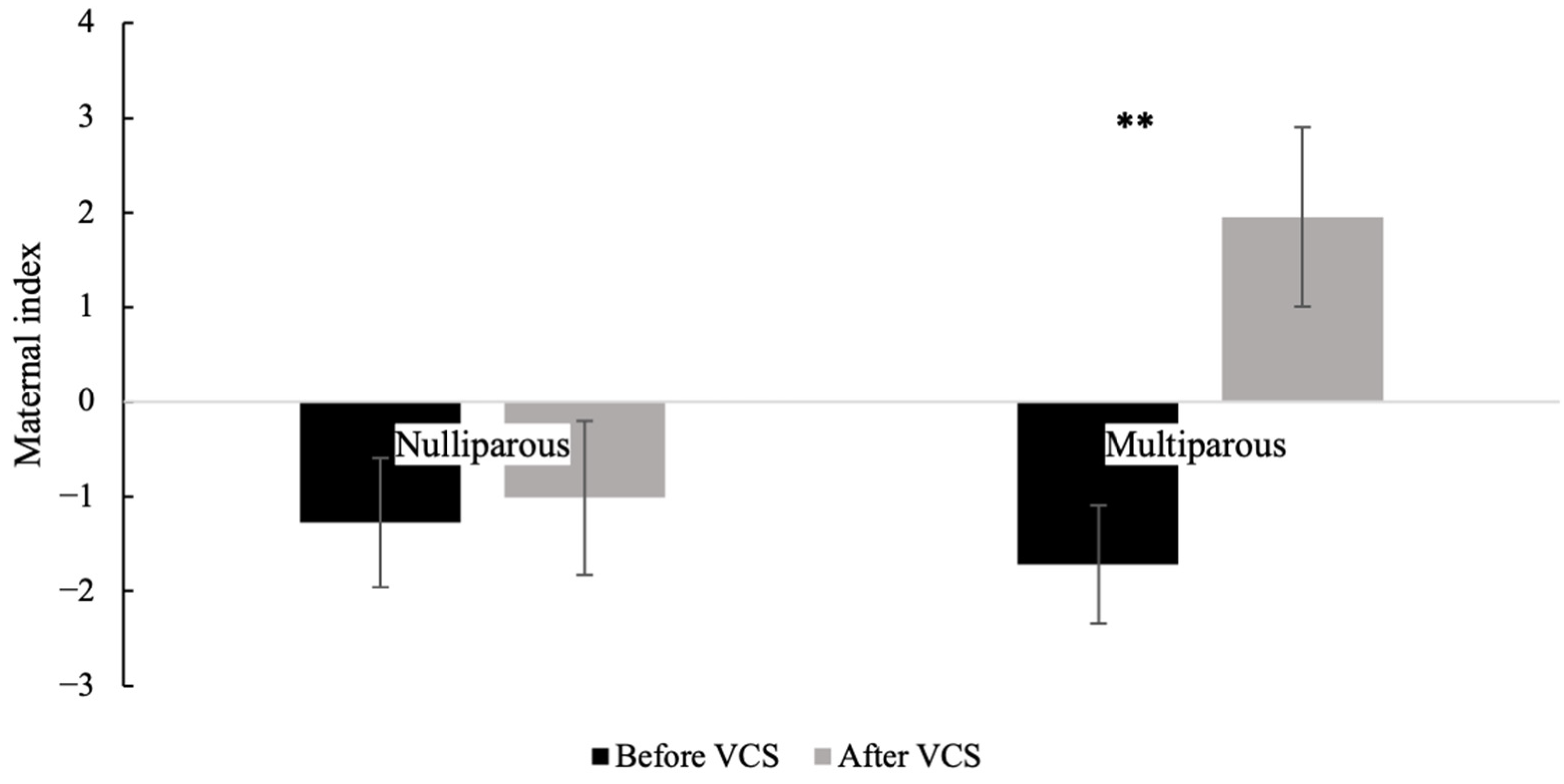

3.8. Maternal Index Comparing Before and After VCS for Each Parity Without Considering Hormonal Treatment

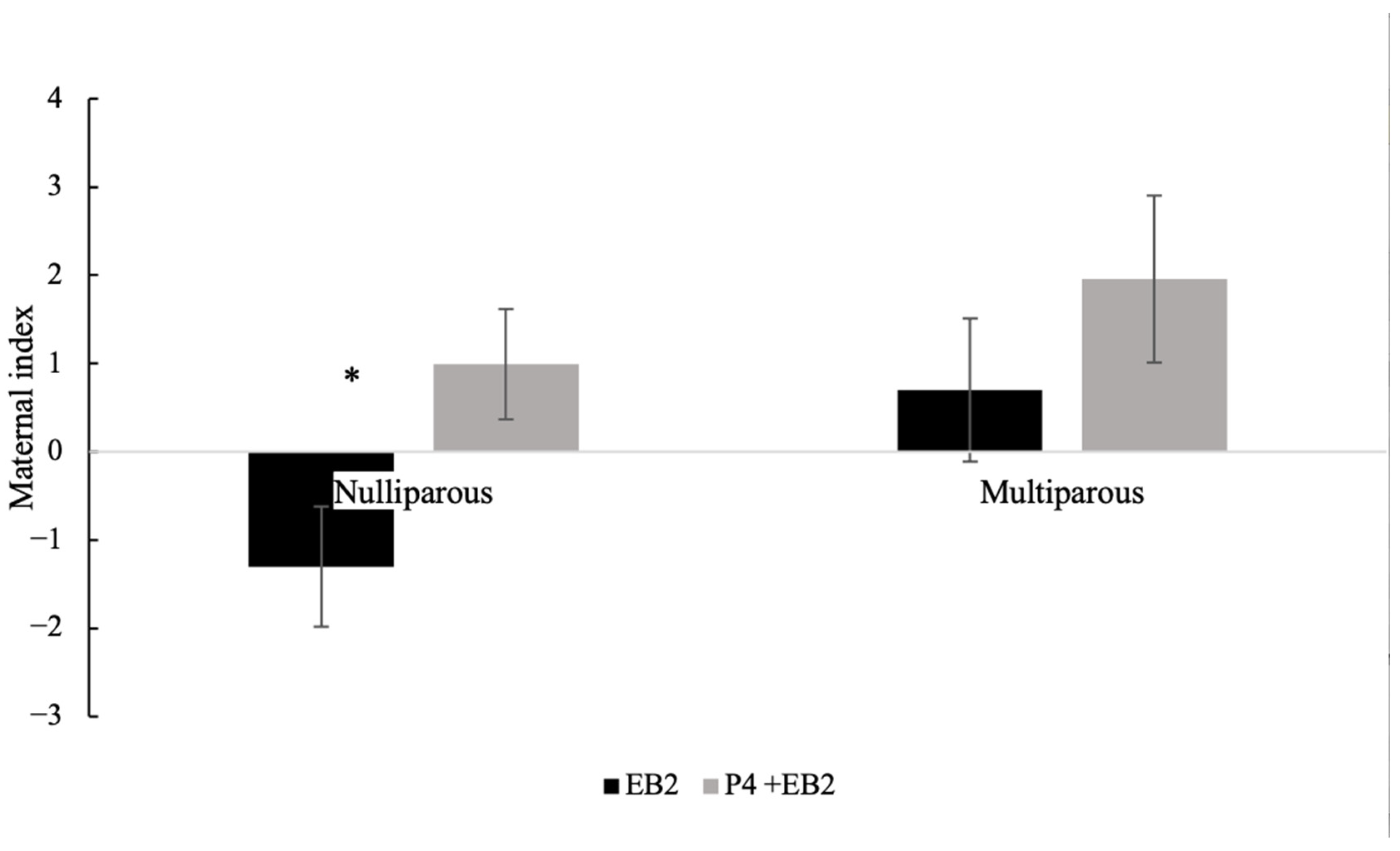

3.9. Maternal Index of Nulliparous or Multiparous Goats, Comparing Between Treatments, Without Considering Stage of Test (Before or After VCS)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P4 | Progesterone |

| VCS | Vagino-cervical stimulation |

| EB2 | Estradiol benzoate |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

References

- Bordi, A.; De Rosa, G.; Napolitano, F.; Litterio, M.; Marino, V.; Rubino, R. Postpartum development of the mother–young relationship in goats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1994, 42, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeyer, A.; Poindron, P.; Orgeur, P. Olfaction mediates the establishment of selective bonding in goats. Physiol. Behav. 1994, 56, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridges, R.S. Neuroendocrine regulation of maternal behavior. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2015, 36, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drescher, K.; Avila, N.R. Comportamiento materno-filial de grandes rumiantes en el trópico. Mundo Pecu. 2012, 8, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Mariscal, G.; Diaz-Sanchez, V.; Melo, A.I.; Beyer, C.; Rosenblatt, J.S. Maternal behavior in New Zealand white rabbits: Quantification of somatic events, motor patterns, and steroid plasma levels. Physiol. Behav. 1994, 55, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, A.A. Estrone and estradiol levels in the ovarian venous blood from rats during the estrous cycle and pregnancy. Biol. Reprod. 1971, 5, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poindron, P.; Le Neindre, P. Endocrine and sensory regulation of maternal behavior in the ewe. Adv. Study Behav. 1980, 11, 75–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Suarez, P.; Damian, J.P.; Soto, R.; Ayala, K.; Zaragoza, J.; Ibarra, R.; Ramírez-Espinosa, J.J.; Castillo, L.; Candanosa Aranda, I.E.; Terrazas, A. Behavioral, Physiological and Hormonal Changes in Primiparous and Multiparous Goats and Their Kids During Peripartum. Ruminants 2024, 4, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickliter, R.E. Hiding behavior in domestic goat kids. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1984, 12, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rørvang, M.V.; Nielsen, B.L.; Herskin, M.S.; Jensen, M.B. Prepartum maternal behavior of domesticated cattle: A comparison with managed, feral, and wild ungulates. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, K.M.; Keverne, E.B. Importance of progesterone and estrogen priming for the induction of maternal behavior by vaginocervical stimulation in sheep: Effects of maternal experience. Physiol. Behav. 1991, 49, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickell, S.; Poindron, P.; Nowak, R.; Ferguson, D.; Blackberry, M.; Blache, D. Maternal behaviour and peripartum levels of oestradiol and progesterone show little difference in Merino ewes selected for calm or nervous temperament under indoor housing conditions. Animal 2011, 5, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, C.M.; Gilbert, C.L.; Lawrence, A.B. Prepartum plasma estradiol and postpartum cortisol, but not oxytocin, are associated with interindividual and breed differences in the expression of maternal behaviour in sheep. Horm. Behav. 2004, 46, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, O.J.; Neumann, I.D. Both oxytocin and vasopressin are mediators of maternal care and aggression in rodents: From central release to sites of action. Horm. Behav. 2012, 61, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kloet, E.R.; Rotteveel, F.; Voorhuis, T.A.; Terlou, M. Topography of binding sites for neurohypophyseal hormones in rat brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985, 110, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendrick, K.M.; Keverne, E.B.; Chapman, C.; Baldwin, B.A. Intracranial dialysis measurement of oxytoxin, monoamine and uric acid release from the olfactory bulb and substantia nigra of sheep during parturition, suckling, separation from lambs and eating. Brain Res. 1988, 439, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, K.M.; Keverne, E.B.; Hinton, M.R.; Goode, J.A. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma concentrations of oxytocin and vasopressin during parturition and vaginocervical stimulation in the sheep. Brain Res. Bull. 1991, 26, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keverne, E.B.; Levy, F.; Poindron, P.; Lindsay, D.R. Vaginal stimulation: An important determinant of maternal bonding in sheep. Science 1983, 7, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krehbiel, D.; Poindron, P.; Lévy, F.; Prud’Homme, M.J. Peridural anesthesia disturbs maternal behavior in primiparous and multiparous parturient ewes. Physiol. Behav. 1987, 40, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mariscal, G.; Poindron, P. Parental care in mammals: Immediate internal and sensory factors of control. In Hormones, Brain and Behaviour; Pfaff, D.W., Arnold, A.P., Etgen, A.M., Farhfbach, S.E., Rubin, R.T., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 215–298. [Google Scholar]

- Coirini, H.; Johnson, A.E.; McEwen, B.S. Estradiol modulation of oxytocin binding in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus of male and female rats. Neuroendocrinology 1989, 50, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, C.M.; Lawrence, A.B. Maternal behaviour in domestic sheep (Ovis aries): Constancy and change with maternal experience. Behaviour 2000, 137, 1391–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, K.M.; Lévy, F.; Keverne, E.B. Importance of vaginocervical stimulation for the formation of maternal bonding in primiparous and multiparous parturient ewes. Physiol. Behav. 1991, 50, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poindron, P.; Terrazas, A.; Montes, M.D.L.L.N.; Serafín, N.; Hernández, H. Sensory and physiological determinants of maternal behavior in the goat (Capra hircus). Horm. Behav. 2007, 52, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poindron, P.; Hernandez, H.; Navarro, M.L.; Gonzalez, F.; Delgadillo, J.A.; Garcia, S. Relaciones madre-cria en cabras. In Proceedings of the XIII Reunion Nacional Sobre Caprinocultura, San Luis Potosi, México, 21 October 1998; pp. 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Romeyer, A.; Poindron, P.; Porter, R.H.; Lévy, F.; Orgeur, P. Establishment of maternal bonding and its mediation by vaginocervical stimulation in goats. Physiol. Behav. 1994, 55, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, R.; Terrazas, A.; Poindron, P.; González-Mariscal, G. Regulation of maternal behavior, social isolation responses, and postpartum estrus by steroid hormones and vaginocervical stimulation in sheep. Horm. Behav. 2021, 136, 105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council (US). Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas, A.; Robledo, V.; Serafín, N.; Soto, R.; Hernández, H.; Poindron, P. Differential effects of undernutrition during pregnancy on the behaviour of does and their kids at parturition and on the establishment of mutual recognition. Animal 2009, 3, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, G.L.; Hooper, R.N.; Slater, M.R.; Hartsfield, S.M.; Matthews, N.S. Detomidine-butorphanol-propofol for carotid artery translocation and castration or ovariectomy in goats. Vet. Surg. 1998, 27, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, M.F.; Uscategui, R.A.R.; Oliveira, M.E.F.; Dias, D.P.M.; Di Filippo, P.A.; Restan, W.A.S.; Valadao, C.A.A.; Coelho, L.A.; Vicente, W.R.R. Evaluación de los efectos cardiorrespiratorios del butorfanol adjunto a un protocolo de anestesia total intravenosa en cabras sometidas a laparoscopia. Arch. De Med. Vet. 2016, 48, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poindron, P.; Otal, J.; Ferreira, G.; Keller, M.; Guesdon, V.; Nowak, R.; Lévy, F. Amniotic fluid is important for the maintenance of maternal responsiveness and the establishment of maternal selectivity in sheep. Animal 2010, 4, 2057–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipka, M.P.; Ford, S.P. Relationship of circulating estrogen and progesterone concentrations during late pregnancy and the onset phase of maternal behavior in the ewe. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1991, 31, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickliter, R.E. Behavior associated with parturition in the domestic goat. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1985, 13, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poindron, P.; Raksanyi, I.; Orgeur, P.; Le Neindre, P. Comparaison du comportement maternel en bergerie à la parturition chez des brebis primipares ou multipares de race Romanov, Préalpes du Sud et Ile-de-France. Genet. Sel. Evol. 1984, 16, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Neindre, P.; Poindron, P.; Delouis, C. Hormonal induction of maternal behavior in non-pregnant ewes. Physiol. Behav. 1979, 22, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, F. The Onset of Maternal Behavior in Sheep and Goats: Endocrine, Sensory, Neural, and Experiential Mechanisms. Adv. Neurobiol. 2022, 27, 79–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbán Esquivel, K.; Damián, J.P.; Díaz Sánchez, V.M.; Rojas Maya, S.; Cano Suárez, P.C.; Ramírez Espinosa, J.J.; Salvador-Fores, O.; Soto-González, R.; Terrazas García, A.M. A comparison of behavioral and biochemical changes associated with pain, between primiparous and multiparous goats around parturition. Austral J. Vet. Sci. 2025, 57, e5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickell, S.L.; Nowak, R.; Poindron, P.; Ferguson, D.; Blache, D. Maternal behaviour at parturition in outdoor conditions differs only moderately between single-bearing ewes selected for their calm or nervous temperament. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2010, 50, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoycheva, S.; Dimitrova, T.; Mondeshka, L.; Markov, N.; Hristov, M. Influence of temperament on maternal behaviour in dairy goats. Sci. Papers. Ser. D 2023, 56, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Finkemeier, M.A.; Oesterwind, S.; Nürnberg, G.; Puppe, B.; Langbein, J. Assessment of personality types in Nigerian dwarf goats (Capra hircus) and cross-context correlations to behavioural and physiological responses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 217, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; Otal, J.; Ramírez, A.; Hevia, M.L.; Quiles, A. Variability in the behavior of kids born of primiparous goats during the first hour after parturition: Effect of the type of parturition, sex, duration of birth, and maternal behavior. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 1772–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, I.I.; Aguli, Z. Maternal and neonatal factors affecting neonatal behaviour in West African Dwarf goats. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 56, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, H.; Serafin, N.; Terrazas, A.M.; Marnet, P.G.; Kann, G.; Delgadillo, J.A.; Poindron, P. Maternal olfaction differentially modulates oxytocin and prolactin release during suckling in goats. Horm. Behav. 2002, 42, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otal, J.; Martinez, M.; Quiles, A.; Hevia, M.L.; Ramirez, A. Effect of litter size and sex in the birth weight of newborn kids and in the behaviour of primiparous goats before, during and after the parturition. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 90, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behavior | Description | Unit of Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Low-pitch bleats | Number of vocalizations emitted by the female with her mouth closed | Frequency |

| High-pitch bleats | Number of vocalizations emitted by the female with her mouth open | Frequency |

| Location changes | Number of times the goat changed position or crossed the quadrants painted on the floor | Frequency |

| Aggression toward kid | Number of times the female threatened, bit, or hit the kid | Frequency |

| Suckling acceptances | Number of times the goat allowed the kid to approach the udders for more than 5 continuous seconds and/or suckle | Frequency |

| Suckling refusals | Number of times the goat did not allow the kid to approach the udders and/or suckle | Frequency |

| Suckling duration | When the female allowed the kid to ingest milk, and it was only considered when the episode lasted for more than 5 continuous seconds | Duration (s) |

| Cleaning of kid | When the female cleaned the kid in a grooming manner | Duration (s) |

| Smelling of kid | When the goat brought its nose close to the kid to sniff it | Frequency |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cano-Suárez, P.C.; Damián, J.P.; Soto, R.; Ayala-Pereyro, K.G.; Ibarra-Trujillo, R.; Castillo-Hernández, L.; Flores-Gasca, E.; Morales-Méndez, R.; Mendoza-Flores, J.E.; Terrazas, A. In Nulliparous and Multiparous Ovariectomized Goats Is Possible to Induce Maternal Behavior with Hormonal Treatment Plus Vagino-Cervical Stimulation. Ruminants 2025, 5, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040046

Cano-Suárez PC, Damián JP, Soto R, Ayala-Pereyro KG, Ibarra-Trujillo R, Castillo-Hernández L, Flores-Gasca E, Morales-Méndez R, Mendoza-Flores JE, Terrazas A. In Nulliparous and Multiparous Ovariectomized Goats Is Possible to Induce Maternal Behavior with Hormonal Treatment Plus Vagino-Cervical Stimulation. Ruminants. 2025; 5(4):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040046

Chicago/Turabian StyleCano-Suárez, Paolo César, Juan Pablo Damián, Rosalba Soto, Karen Guadalupe Ayala-Pereyro, Rocío Ibarra-Trujillo, Laura Castillo-Hernández, Enrique Flores-Gasca, Rocío Morales-Méndez, Jorge Eduardo Mendoza-Flores, and Angélica Terrazas. 2025. "In Nulliparous and Multiparous Ovariectomized Goats Is Possible to Induce Maternal Behavior with Hormonal Treatment Plus Vagino-Cervical Stimulation" Ruminants 5, no. 4: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040046

APA StyleCano-Suárez, P. C., Damián, J. P., Soto, R., Ayala-Pereyro, K. G., Ibarra-Trujillo, R., Castillo-Hernández, L., Flores-Gasca, E., Morales-Méndez, R., Mendoza-Flores, J. E., & Terrazas, A. (2025). In Nulliparous and Multiparous Ovariectomized Goats Is Possible to Induce Maternal Behavior with Hormonal Treatment Plus Vagino-Cervical Stimulation. Ruminants, 5(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040046