1. Introduction

Population ageing has become one of the most profound demographic transformations of the twenty-first century. In particular, the number of individuals aged 80 years and above—the “oldest-old”—is increasing rapidly across both high- and middle-income societies. While early ageing research primarily focused on survival and chronic disease, more recent work has emphasized functional independence, especially limitations in activities of daily living (ADL), as a central indicator of quality of life at very advanced ages [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

A wide range of studies document persistent socioeconomic gradients in health and functional ability across the life course. Educational attainment, income, and occupational status are strongly associated with healthier ageing trajectories and lower risks of disability [

8,

9,

10], including among the oldest-old [

2,

4,

11]. Within life-course theory, these patterns are often interpreted through the lenses of cumulative advantage and continuity versus convergence. Cumulative advantage predicts that early-life socioeconomic resources accumulate over time and remain visible even in late life, whereas convergence or age-as-leveler hypotheses suggest that biological ageing and selective mortality may attenuate or eliminate socioeconomic gradients at very advanced ages.

Education plays a particularly central role in these frameworks. It is largely determined early in life and shapes later outcomes through multiple pathways, including health literacy, long-term health behaviours, occupational exposures, and access to social and institutional resources [

12]. Whether educational gradients in functional independence persist among individuals aged 80 and above therefore provides an important test of competing life-course perspectives.

Despite this, most empirical studies continue to pool the oldest-old with younger elderly populations (e.g., 60+ or 65+), making it difficult to assess whether socioeconomic gradients survive into very advanced ages. Other strands of research emphasize late-life medical care and institutional support, potentially downplaying the role of long-term socioeconomic and behavioural processes. As a result, it remains unclear to what extent functional independence among the oldest-old reflects current care settings versus cumulative life-course resources.

This study addresses this gap using harmonized cross-national data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Focusing on individuals aged 80 years and above, we examine whether educational attainment remains associated with limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) after accounting for age, gender, physical functioning, living arrangements, and country fixed effects. By explicitly targeting the oldest-old, this analysis contributes to the literature on life-course inequality and successful ageing and provides policy-relevant evidence on the foundations of well-being at very advanced ages.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Sample

The empirical analysis is based on data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), a large-scale, cross-national survey designed to collect harmonized information on health, socioeconomic status, and family networks among older populations. SHARE provides detailed and comparable data across multiple European countries, making it particularly suitable for studying ageing-related outcomes in an international context. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.5.2, The R Project for Statistical Computing,

https://cran.r-project.org/).

This study focuses on respondents aged 80 years and above. Restricting the sample to the oldest-old allows us to examine functional independence at very advanced ages, a group that is often pooled with younger elderly populations in previous research. After excluding observations with missing information on key variables, the final analytical sample consists of 11,540 individuals across multiple European countries.

The analytical sample was derived from the Gateway Harmonized SHARE Wave 9 dataset. Although SHARE is a panel study, the present analysis uses a single cross-section in order to maximize sample size among the oldest-old and to avoid attrition and selective survival biases inherent in long panels at very advanced ages. From 158,764 person-wave observations, we restricted the data to respondents with valid age information and selected individuals aged 80 years and above. After excluding observations with missing information on ADL status, education, physical functioning, living arrangement, gender, or country, the final sample consisted of 11,540 individuals.

2.2. Outcome Variable

Functional independence is measured using limitations in activities of daily living (ADL). The dependent variable is a binary indicator equal to one if the respondent reports at least one limitation in basic daily activities, such as dressing, bathing, or eating, and zero otherwise [

13]. ADL limitations are widely used in gerontology and health economics as a core indicator of functional dependency and quality of life.

2.3. Key Explanatory Variables

The main explanatory variables capture socioeconomic status, lifestyle-related physical functioning, and living arrangements. Socioeconomic status is proxied by years of education, which reflects long-term life-course resources and is largely predetermined before old age. Lifestyle-related physical functioning is measured by the absence of walking difficulties, serving as an indicator of preserved mobility and physical capacity. Living arrangements are captured by an indicator for institutional residence, distinguishing individuals living in care institutions from those residing in the community.

In addition, all models control for age and gender. To account for cross-national differences in institutional, cultural, and healthcare contexts, country fixed effects are included in all specifications.

2.4. Empirical Strategy

We estimate logistic regression models to examine the probability of experiencing ADL limitations among individuals aged 80 and above. The baseline specification includes education, age, gender, and country fixed effects. Subsequent models add physical functioning and living arrangements to assess whether socioeconomic gradients persist after accounting for lifestyle and care-related factors. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are reported for ease of interpretation.

3. Results

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for individuals aged 80 years and above. Approximately 11% of respondents report at least one limitation in activities of daily living (ADL). Educational attainment averages 9.6 years, with substantial variation across individuals. Only about 9% report no walking difficulties, and approximately 3% reside in institutions.

Table S1 reports country composition of the analytical Sample.

Table 2 presents odds ratios from logistic regression models predicting the likelihood of reporting at least one ADL limitation. Educational attainment is negatively associated with ADL limitations: each additional year of education is associated with a statistically significant reduction in the odds of functional dependency (OR = 0.978; 95% CI: 0.964–0.993). Age is strongly associated with higher odds of ADL limitations, and women exhibit slightly higher odds than men.

Physical functioning, proxied by the absence of walking difficulties, is also associated with substantially lower odds of ADL limitations (OR = 0.791; 95% CI: 0.636–0.974). Institutional residence is not significantly associated with ADL limitations once age, gender, education, physical functioning, and country fixed effects are included.

Table 3 shows that the coefficient for education remains stable across alternative model specifications that sequentially add physical functioning and institutional residence.

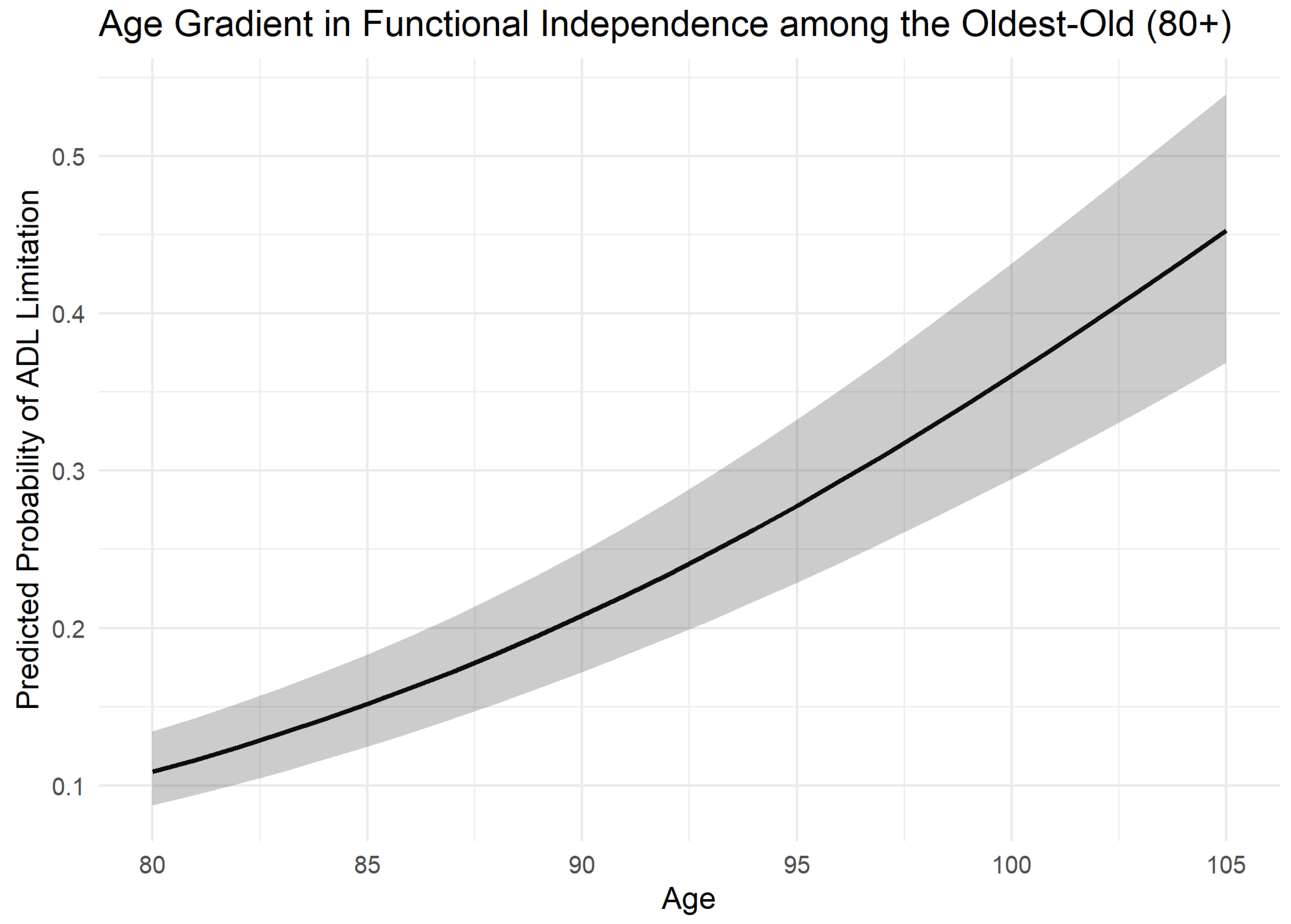

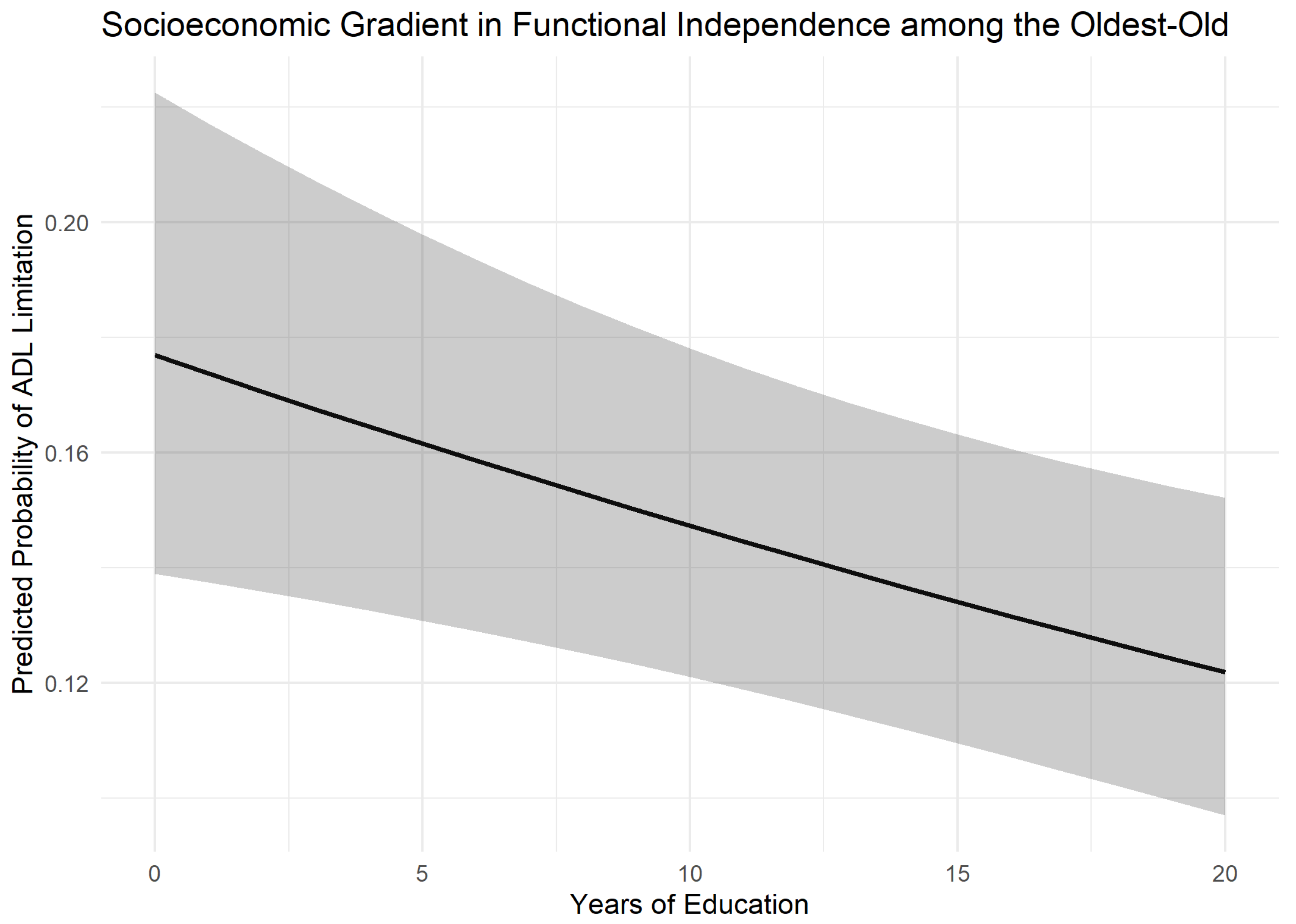

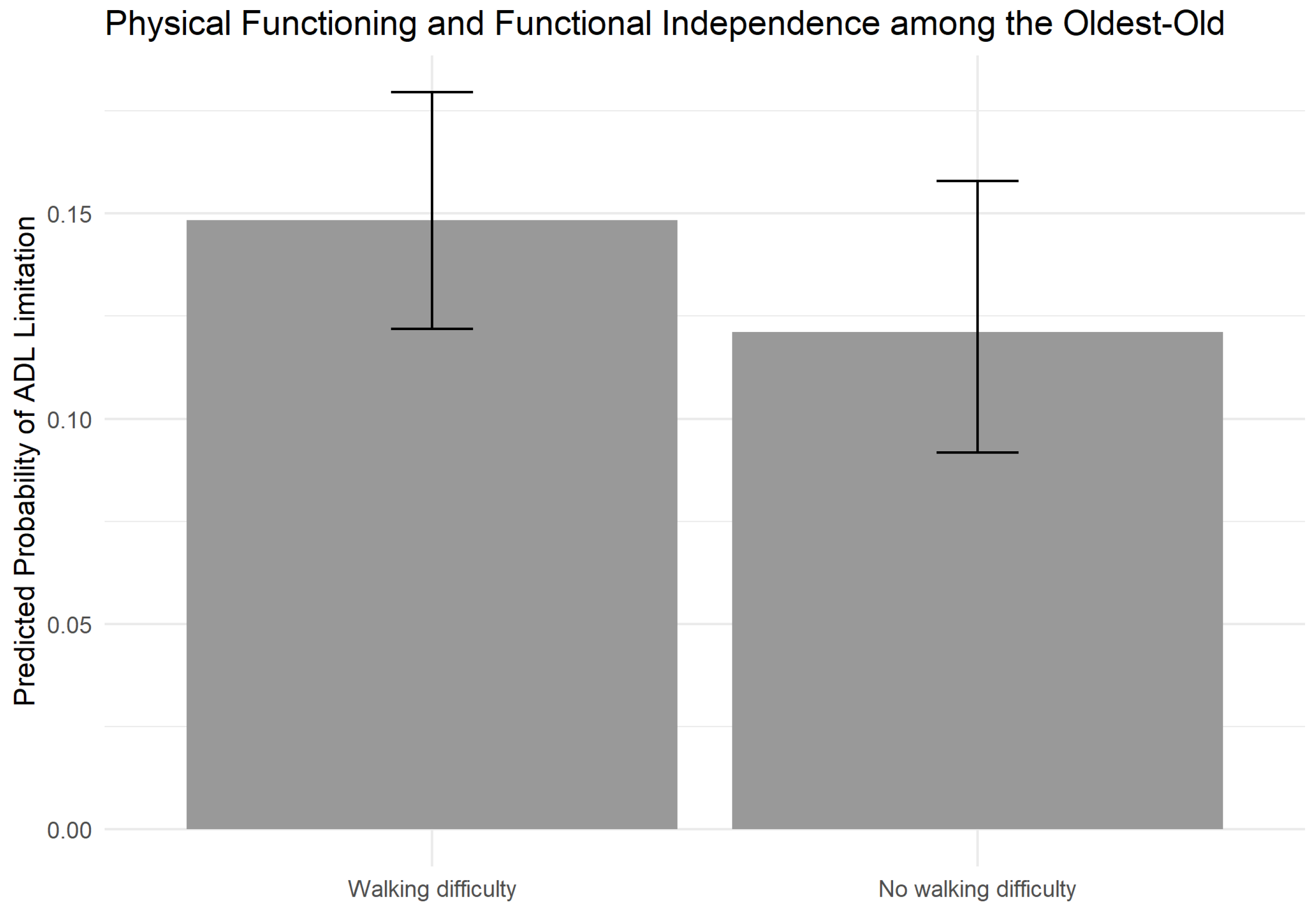

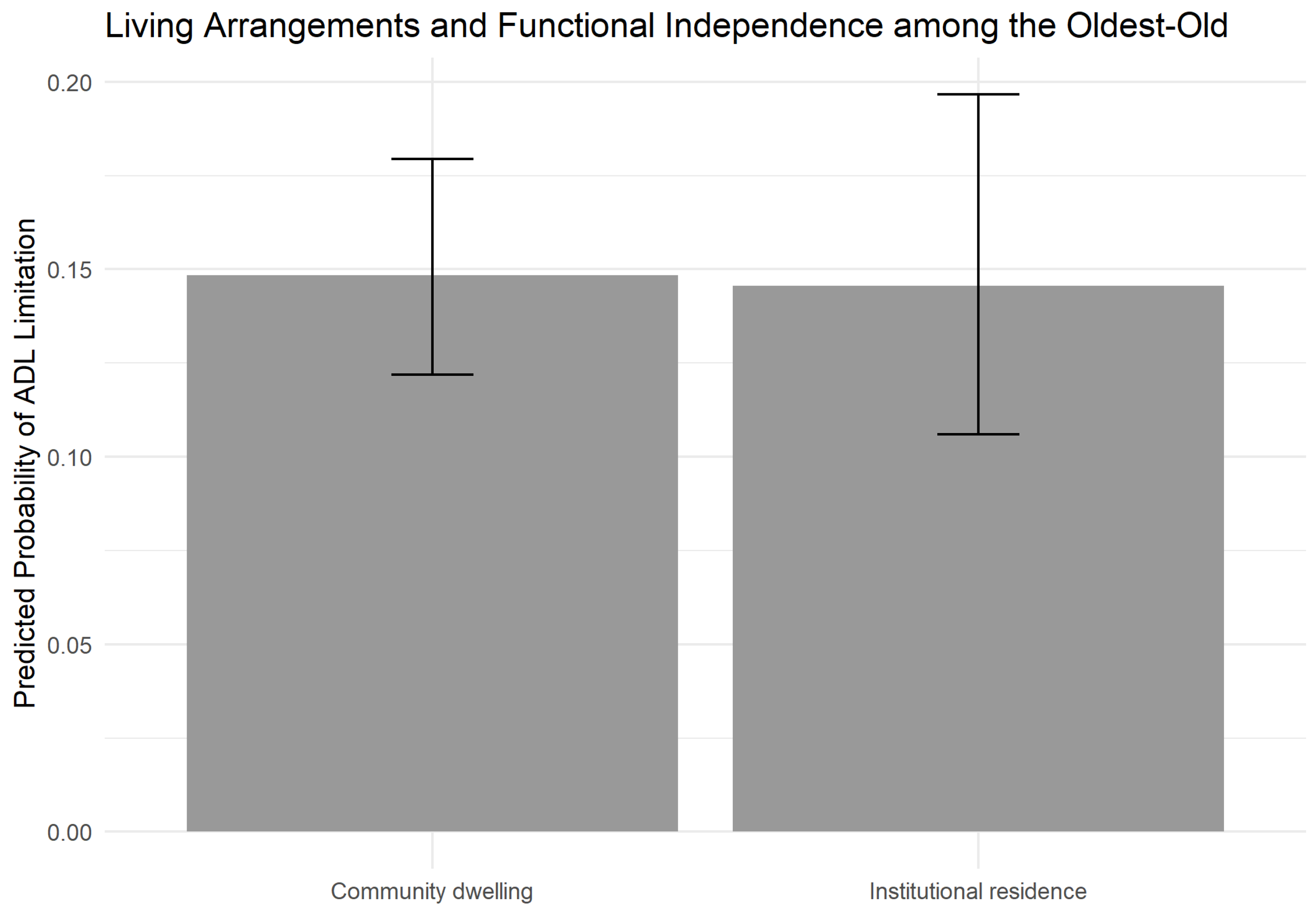

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate predicted probabilities derived from the multivariable model.

Figure 1 shows a steep age gradient in ADL limitations within the 80+ population.

Figure 2 shows that higher educational attainment is associated with a lower predicted probability of ADL limitations [

14].

Figure 3 shows large differences in predicted ADL limitations by physical functioning status.

Figure 4 shows no independent difference by institutional residence after adjustment [

3,

15,

16].

4. Robustness and Additional Considerations

Several features of the analysis support the robustness of the findings. First, the core results are stable across alternative model specifications that sequentially introduce lifestyle and care-related controls. Second, the inclusion of country fixed effects ensures that the estimated associations are not driven by cross-national differences in healthcare systems or long-term care regimes.

While the analysis focuses on ADL limitations as a central indicator of functional independence, the results are consistent with a broader interpretation of quality of life among the oldest-old. The persistence of the education gradient after controlling for physical functioning and living arrangements reinforces the importance of adopting a life-course perspective when evaluating outcomes at very advanced ages.

Supplementary Figure S1 presents sex-stratified age gradients in functional independence, confirming that the age-related increase in ADL limitations is observed for both men and women.

Supplementary Figure S2 further demonstrates that the negative association between educational attainment and ADL limitations remains robust across alternative model specifications. A detailed sample flow is reported in

Supplementary Figure S3.

To assess whether our results depend on the dichotomization of ADL limitations, we estimated an additional negative binomial model using the number of ADL limitations (0–6) as the dependent variable (

Supplementary Table S2).

The education gradient remains statistically significant and of similar magnitude, confirming that higher educational attainment is associated not only with a lower probability of any ADL limitation but also with fewer limitations in total. Age and physical functioning continue to be strong predictors of ADL severity, and institutional residence is positively associated with the number of ADL limitations, consistent with selection into care based on prior health status.

5. Discussion

This study examined socioeconomic, physical, and care-related correlates of functional independence among individuals aged 80 years and above using harmonized SHARE data. By focusing explicitly on the oldest-old, this analysis contributes to a growing focus in the literature on life-course inequality and quality of life at very advanced ages [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

5.1. Education, Life-Course Resources, and Selective Survival

The persistence of educational gradients in ADL limitations among the oldest-old is consistent with cumulative advantage and continuity perspectives in health inequality. At the same time, these observed gradients may also reflect selective survival, whereby individuals with higher education are more likely to survive into advanced ages in better health. Our results should therefore be interpreted as associations consistent with life-course processes rather than as direct evidence of causal accumulation.

5.2. Physical Functioning as a Proximal Determinant

Physical functioning, measured by walking ability, is strongly associated with ADL limitations. Importantly, educational gradients persist throughout physical functioning, indicating that socioeconomic differences in functional independence are not fully explained by current physical capacity. We do not interpret this as evidence of mediation, but rather as showing that education remains associated with ADL outcomes even after accounting for a key proximal health indicator.

Supplementary Table S2 further shows that educational attainment is also significantly associated with the number of ADL limitations, even when physical functioning is controlled for.

5.3. Institutional Residence and Selection

The lack of an independent association between institutional residence and ADL limitations should be interpreted cautiously. Institutionalization is likely endogenous to functional decline, reflecting selection based on prior health and care needs. Moreover, SHARE’s sampling of institutionalized populations differs across countries, further limiting causal interpretation. Our results therefore indicate that institutional residence in these data is not an independent correlate of ADL once observed characteristics are controlled for, not that care settings are unimportant.

5.4. Gender, Age, and Heterogeneity

Women exhibit higher odds of ADL limitations, consistent with the morbidity–mortality paradox whereby women live longer but with higher disability. Age gradients remain steep even within the 80+ population, highlighting substantial heterogeneity among the oldest-old.

5.5. Cross-National Context

Country fixed effects indicate substantial cross-national heterogeneity. Estimates of country fixed effects are reported in

Table 2 and

Table S2. These differences likely reflect variation in welfare regimes, long-term care systems, and cultural contexts, although identifying specific mechanisms lies beyond the scope of this study.

5.6. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the analysis is based on cross-sectional data, which precludes causal inference regarding the relationships between socioeconomic resources, physical functioning, and functional independence. Second, although SHARE provides high-quality harmonized data, selective survival and non-response among the oldest-old may lead to an underrepresentation of individuals with severe disability, potentially biasing estimates toward healthier respondents. Third, key explanatory variables such as physical functioning and ADL limitations rely on self-reported measures, which may be subject to reporting heterogeneity across individuals and countries. Finally, while country fixed effects account for unobserved national-level differences, the analysis does not explicitly identify specific institutional or policy mechanisms underlying cross-national variation. Future research using longitudinal designs and richer contextual data would help to address these limitations and further clarify the life-course determinants of functional independence at very advanced ages.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the determinants of functional independence among individuals aged 80 years and above using harmonized data from the SHARE survey. By focusing on the oldest-old, the analysis provides novel evidence that socioeconomic inequality in functional health persists well into very advanced ages. Educational attainment remains a significant protective factor against limitations in activities of daily living, even after accounting for age, gender, physical functioning, living arrangements, and cross-national differences.

Preserved physical functioning—proxied by the absence of walking difficulties—is also strongly associated with lower odds of functional dependency, underscoring the importance of maintaining mobility for autonomy in daily life among the oldest-old. In contrast, institutional residence does not exhibit an independent association with ADL limitations once individual characteristics are taken into account, suggesting that care settings primarily reflect underlying health needs rather than acting as a direct cause of functional decline.

Taken together, these findings indicate that successful ageing at very advanced ages reflects long-term life-course processes rather than late-life medical care alone. Policies aimed at improving quality of life in ageing societies should therefore adopt a life-course perspective, emphasizing education, health literacy, and the promotion of physical functioning as key foundations for autonomy and well-being among the oldest-old.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jal6010016/s1: Figure S1: Sex-Stratified Age Gradients in Functional Independence among the Oldest-Old; Figure S2: Sensitivity Analysis Using Alternative Functional Measures; Figure S3: Sample selection flow for the SHARE oldest-old population; Table S1:Country Composition of the Oldest-Old (80+) Analytical Sample; Table S2: Determinants of the Number of ADL Limitations among Individuals Aged 80 and Above (Negative Binomial Model).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study uses secondary, anonymized data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), which is publicly available for research purposes and does not involve direct contact with human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Informed consent was obtained by the SHARE project from all participants at the time of data collection.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) upon reasonable request and subject to data access regulations. Information on data access is available at

http://www.share-project.org (accessed on 25 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) project for providing access to the harmonized data used in this study. SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission, the U.S. National Institute on Aging, and national funding agencies participating in SHARE. The interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Santoni, G.; Meinow, B.; Wimo, A.; Marengoni, A.; Fratiglioni, L.; Calderon-Larranaga, A. Using an integrated clinical and functional assessment tool to describe the use of social and medical care in an urban community-dwelling Swedish older population. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Hesketh, T.; Christensen, K.; Vaupel, J.W. Survival, disabilities in activities of daily living, and physical and cognitive functioning among the oldest-old in China: A cohort study. Lancet 2017, 389, 1619–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrettos, I.; Anagnostopoulos, F.; Voukelatou, P.; Kyvetos, A.; Theotoka, D.; Niakas, D. Does old age comprise distinct subphases? Evidence from an analysis of the relationship between age and activities of daily living, comorbidities, and geriatric syndromes. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2024, 28, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenner, J.; Albrecht, A.; Zimmermann, J. Challenges in research on the oldest old: The example of inequalities in functional health. KZfSS Kölner Z. Soziol. Sozialpsychol. 2025, 77, 881–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briede-Westermeyer, J.C.; Fuentes-Sepúlveda, M.; Lazo-Sagredo, F.; Molina-Reyes, A.; Lagos-Huenuvil, V.; Pérez-Villalobos, C. Frequency of daily living activities in older adults and their relationship with sociodemographic characteristics: A survey-based study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Self-rated physical and mental health among older adults 80 years and older: Cross-sectional results from a national community sample in Thailand. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, S.B.; Pulkki, J.; Aaltonen, M.; Jämsen, E.; Raitanen, J.; Enroth, L. Frequency and predictors of emergency department visits among the oldest old in Finland: The Vitality 90+ Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crimmins, E.M. Social hallmarks of aging: Suggestions for geroscience research. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 63, 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, M. Socioeconomic status and ADL disability of older adults: Cumulative health effects, social outcomes, and impact mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.; Wilkinson, R. Social Determinants of Health, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moormann, K.I.; Pabst, A.; Bleck, F.; Löbner, M.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; van der Leeden, C.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Social isolation in the oldest-old: Determinants and the differential role of family and friends. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, D.M.; Lleras-Muney, A. Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence; Working Paper No. 12352; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Ford, A.B.; Moskowitz, R.W.; Jackson, B.A.; Jaffe, M.W. Studies of illness in the aged: The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963, 185, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. What factors are associated with functional impairment among the oldest old? Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1092775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Simonsick, E.M.; Salive, M.E.; Wallace, R.B. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Z.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Hong, Z. Lifestyle and ADL as prioritized factors influencing all-cause mortality risk among the oldest old: A population-based cohort study. Inquiry 2024, 61, 00469580241235755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Börsch-Supan, A.; Brandt, M.; Hunkler, C.; Kneip, T.; Korbmacher, J.; Malter, F.; Zuber, S. Data resource profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osawa, Y.; Abe, Y.; Takayama, M.; Arai, Y. Six-year transition patterns of activities of daily living in octogenarians: Tokyo oldest old in total health study. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |