1. Introduction

Climate change represents one of the most pressing global challenges of our time, and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 will require the active participation of all segments of society [

1]. While considerable research has focused on the climate behaviours and engagement of younger and mainstream populations, there remains a marked lack of attention to older adults—particularly those from migrant backgrounds [

2]. Among them, older Chinese migrants living in Western societies are significantly under-represented in both academic literature and policy discourse, despite their lived experiences and culturally embedded sustainable practices [

3,

4].

Shaped by long-standing values such as thrift and intergenerational responsibility, many older Chinese migrants maintain everyday habits that align with low-carbon lifestyles, including recycling and energy conservation [

5,

6,

7]. However, their broader engagement in climate action and participation in policy initiatives is often hindered by multiple barriers, including language limitations, cultural differences, and the absence of tailored, accessible information channels [

8,

9]. These challenges not only restrict older migrants’ willingness or ability to participate in climate initiatives but also lead to the systematic exclusion of their lived experiences and cultural knowledge from formal sustainability efforts—thereby missing critical opportunities to advance community-based and intergenerational climate transitions [

7,

10,

11].

Co-design has emerged as a promising participatory approach that actively involves end-users in the creation of solutions that reflect their lived realities [

12,

13]. Co-design has demonstrated effectiveness across multiple domains—including ageing, community planning, and environmental communication—by ensuring that interventions are not only user-driven, but also culturally and socially contextualised [

12,

14,

15,

16]. Yet its application in engaging older migrants—particularly older Chinese adults—in climate action remains underexplored. Few studies have considered how to integrate their daily practices, familial roles, and preferred modes of communication into climate engagement strategies.

To address this gap, this study focuses on older Chinese migrants in London, employing a series of co-design workshops to explore the following research questions:

RQ1: In what ways do older Chinese migrants demonstrate sustainable behaviours through their daily routines?

RQ2: How do their social roles—particularly within the family—influence their understanding of and participation in low-carbon activities?

RQ3a: Through which information channels do they engage with climate-related content?

RQ3b: Which message formats do they perceive as most trustworthy and effective?

This inquiry is framed through the lens of Sense-making theory [

17], focusing on:

Identity cconstruction: How do participants perceive their roles within family and community contexts?

Social process: How is climate-related information accessed and circulated through networks such as WeChat groups and community associations?

Cues: What low-carbon themes resonate most strongly with them?

Plausibility judgement: How do they evaluate the credibility and relevance of climate information, particularly in the context of net-zero messaging?

By addressing these questions, the study aims to illuminate the under-recognised role and potential of older Chinese migrants in climate action, identifying both the barriers to their participation and strategies for effectively engaging them. The findings offer practical guidance for designers, policymakers, and community stakeholders in developing more inclusive communication strategies that reflect participants’ language preferences, media use, and cultural values.

2. Research Background

2.1. Older Adults and Climate Action

Climate change is increasingly recognised as a pressing global challenge that requires coordinated and inclusive responses across all age groups, including older adults [

10]. Older individuals play a vital role in shaping sustainable behaviours within families and communities, drawing on values such as thrift, resilience, and intergenerational responsibility [

5]. However, research and policy discourses have historically marginalised this demographic, with most climate engagement strategies disproportionately focused on younger or digitally engaged populations [

18,

19,

20]. Consequently, there remains a significant gap in understanding how older adults—particularly those from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities—access, interpret, and act on climate-related information [

21].

Engaging older adults in climate solutions offers not only social justice and inclusion benefits, but also practical advantages for behavioural change at the household and community level [

2]. As trusted sources of knowledge and family influencers, older adults can initiate intergenerational climate dialogues and serve as behavioural role models for younger generations [

22]. Their participation can significantly enhance the cultural relevance, credibility, and adoption of climate initiatives at the community level.

2.2. Migrant Cultural Adaptation and Participatory Community Approaches

Migrants undergo unique processes of cultural adaptation and integration, which significantly shape their values, behaviours, and lifestyles [

23]. Berry’s acculturation theory conceptualises this as an ongoing negotiation of identity and cultural practice, often influencing attitudes toward environmental sustainability [

24]. Among older Chinese migrants, traditional values such as frugality, collectivism, and moral responsibility often give rise to environmentally conscious behaviours—though these may not be explicitly framed as “climate actions” [

25,

26].

Despite their embedded sustainable practices, these cultural forms of environmental engagement are often overlooked in dominant climate narratives. Recognising and incorporating these perspectives is essential for designing effective, culturally resonant climate communication and interventions [

27,

28]. Scholars have advocated for intercultural approaches that respect the lived practices and world-views of migrant communities [

29,

30,

31].

Notable examples include the Green Zones Initiative in Los Angeles—a community-led environmental justice programme targeting heavily polluted Latino neighbourhoods. By using cumulative impact screening tools and integrating green jobs, health equity, and environmental remediation, the initiative successfully mobilised community engagement and contributed to policy changes such as the “Clean Up Green Up” ordinance [

32,

33]. Similar efforts in Malaysia empower women, youth, and marginalised groups to participate in climate action [

34].

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) has emerged as a foundational principle in working with minority and migrant populations. This model treats community members as equal partners, recognising their knowledge and perspectives as crucial to shaping sustainable solutions. Through shared learning and capacity building, CBPR facilitates long-term community empowerment—especially vital in cultural contexts where formal “climate action” may not be a familiar concept [

35].

2.3. Climate Change Communication and Information Channels

Effective communication with ethnically diverse communities requires a culturally resonant approach that takes into account their values, lived histories, and material conditions. As Moser and Dilling (2011) argue, the framing of climate messages strongly influences acceptance among marginalised groups [

36]. Migrants often carry environmental knowledge from their countries of origin, which can shape how they perceive and respond to sustainability initiatives in the host country [

37,

38]. Pfeffer and Stycos (2002) found that migrants from environmentally degraded or resource-scarce regions tend to be more receptive to conservation messaging [

39].

Climate communicators should build on these prior experiences rather than disregard them. Messages that link sustainability to immediate concerns such as health, financial security, or community wellbeing are often more persuasive. For example, Hoffman et al. (2020) found that urban heat island effects disproportionately impact communities of colour, making health-focused messaging a powerful entry point for climate adaptation strategies [

40].

For older adults, effective climate communication must also address specific challenges such as digital literacy, language barriers, and information overload [

41,

42]. Older migrants, in particular, face compounded barriers due to limited access to culturally relevant resources [

43]. Research highlights the need for clear, visually engaging, and culturally adaptive materials—such as bilingual content and culturally significant imagery—to improve comprehension and relevance [

27,

44].

In ethnic communities, communication often hinges on the credibility of the messenger. Leveraging trusted networks and community figures can significantly enhance message uptake [

45,

46]. The classic “opinion leader” concept remains applicable; influential individuals within communities often act as intermediaries who validate and disseminate key information [

47]. Intergenerational communication also plays a critical role; youth often serve as “cultural brokers” in immigrant families, helping to transfer information to older generations [

48,

49].

For older Chinese migrants, trusted media and social platforms—such as Chinese-language television, WeChat, and local associations—play a central role in shaping perceptions of climate change and influencing action [

50,

51].

2.4. Co-Design: Collaborative Approaches for Inclusive Climate Action

Co-design is a participatory methodology that actively involves target users in the development of solutions, ensuring alignment with their lived experiences and actual needs [

12]. Widely adopted in ageing and environmental contexts, co-design has proven effective in developing inclusive, sustainable interventions [

13,

52,

53].

Its strength lies in power-sharing and inclusivity, enabling marginalised communities to shape interventions from within. While co-design has gained traction in healthcare and elder services, its application at the intersection of ageing, migration, and climate action remains underexplored.

2.5. Theoretical Framework: Sense-Making

This study adopts Weick’s (1995) Sense-making framework, which views meaning-making as an active process grounded in identity, social interaction, environmental cues, and plausibility judgments [

17]. The model is especially suitable for exploring how older migrants interpret and respond to climate information in complex, culturally embedded contexts. Complementing this, Berry’s acculturation theory (1997) underscores how migrants negotiate cultural identities between heritage and host societies, shaping their communication and environmental behaviours [

24].

Lynam and Fletcher (2015) extend Sense-making into complex adaptive systems, proposing that meaning emerges not from static processing but from lived experience, cultural norms, and social feedback. Their use of micro-narratives and self-signification provides a flexible lens to capture how individuals navigate climate complexity without imposed researcher frameworks [

54].

This combined theoretical foundation is particularly well-suited to older Chinese migrants, who operate within hybrid cultural spaces and rely on embodied, community-based knowledge. It aligns closely with the co-design methodology employed in this study, where participants not only share narratives but also help shape how those narratives are interpreted and translated into practice.

2.6. Research Gaps and Contributions

Despite increasing attention to ageing, migration, and climate communication as separate areas of study, there is a notable absence of research that integrates these dimensions to examine how older migrants—especially those from culturally distinct communities like Chinese migrants—engage with climate action. While older adults are acknowledged as potential agents of sustainability, little is known about how their migration histories, cultural identities, and community roles shape their environmental behaviours and communication preferences.

Current climate engagement strategies often assume linear models of behaviour change and overlook the complex ways individuals make sense of sustainability messages in their everyday lives. For older Chinese migrants, who operate in hybrid cultural spaces and rely on informal, community-based information flows, such assumptions may be particularly limiting.

To address this gap, this study adopts a co-design workshop approach as both a research method and an engagement tool. Co-design provides a structured, participatory platform to uncover the user journeys, social roles, and information preferences of older Chinese migrants—insights that are rarely accessible through traditional surveys or top-down interventions. Understanding these dimensions is essential for designing inclusive communication strategies that resonate with this group’s lived experience.

The workshops are analytically framed through Sense-making theory, which emphasises how people construct meaning through identity, context, and interaction. By capturing how participants interpret climate information in relation to their familial roles, cultural values, and community networks, the study explores the process by which information becomes actionable.

By integrating co-design with a Sense-making framework, this study makes three key contributions:

Empirical contribution: It offers one of the first in-depth examinations of climate-related behaviours, social roles, and communication practices among older Chinese migrants—an area that has received limited scholarly attention despite its clear policy and practical relevance.

Theoretical contribution: It extends the application of Sense-making theory to the intersection of ageing, migration, and climate engagement—illustrating how identity, cultural hybridity, and everyday reasoning processes shape environmental action.

Practical contribution: Drawing on lived experiences rather than abstract assumptions, the study proposes culturally inclusive and age-friendly communication strategies, tailored to the specific needs and strengths of ageing migrant communities.

3. Methods

This study adopts a co-design workshop methodology informed by Sense-making theory to explore how older Chinese migrants engage with climate-related behaviours and communication. The approach recognises that climate action among ageing, culturally diverse populations is shaped by personal experiences, social roles, and contextual understanding.

Given the limited literature on climate engagement within ageing migrant communities, co-design offers a participatory opportunity to uncover practical insights grounded in lived experience. The method enables participants not only to articulate their behaviours and values, but also to reflect on how identity, networks, and cultural background shape their information preferences. This supports the study’s aim to develop culturally inclusive and age-sensitive climate communication strategies.

3.1. Recruitment and Procedure

3.1.1. Participant Recruitment

Community-based recruitment strategies were employed to ensure inclusivity and relevance. London was chosen due to its high concentration of older Chinese migrant populations and the well-established Chinese community organisations that facilitated access and recruitment. Recruitment posters were shared with the London Mandarin Evangelical Church (LMEC) and North London Chinese Association (NLCA), leveraging the researcher’s pre-existing connections with these communities. These organisations provided access to older Chinese migrants who fit the study’s target demographic (aged 50–85).

The two organisations were intentionally selected to reflect internal diversity within the Chinese migrant community. The NLCA is one of the largest Chinese associations in North London, with an active online platform and annual events such as Chinese New Year celebrations. Its broad membership base includes individuals with diverse regional and occupational backgrounds. The LMEC, located in central London, serves a transient, city-wide Mandarin-speaking population from various regions of China. This stands in contrast to other community hubs that may predominantly attract Hong Kong or Southeast Asian Chinese migrants. Together, these sites allowed the study to reach a wider cross-section of Mandarin-speaking older migrants in London.

The recruitment process prioritised participants who were fluent in reading and writing Mandarin or Cantonese and who were cognitively healthy, as the workshop required active engagement, reading comprehension, and written responses. Special care was taken to avoid recruiting individuals with dexterity challenges or severe language barriers that could hinder participation. Moreover, attention was paid to sampling a demographically varied group in terms of education levels, occupational history, and gender, in order to enrich the data and capture multiple perspectives within the small sample size.

3.1.2. Pilot Study

Before the formal workshop, three older participants were invited to conduct pilot research and make suggestions for a co-design workshop within Brunel University. Following initial participant feedback, several refinements were made to enhance clarity, accessibility, and engagement:

Simplified worksheet structure—The user journey section was split into weekday and weekend activities for easier comprehension.

Pre-prepared sticker responses—Certain tasks were modified to use stickers, reducing cognitive and physical effort for participants.

Larger print formats—Worksheets were enlarged to A3 size to accommodate participants with vision impairments.

Clearer task instructions—Additional examples and visuals were incorporated to ensure participants fully understood the tasks before discussions began.

This pilot phase ensured that materials were culturally and physically accessible for older Chinese participants, who may face challenges related to vision, mobility, or language processing.

3.2. Sampling Strategy

A purposive sampling strategy targeted small-group interaction (6–8 per session) while ensuring insight variation. Two workshops were conducted with a total of 13 participants from varied professions—including retirees, teachers, homemakers, and small business owners.

Table 1 summarises participant information.

3.3. Workshop Design and Procedure

Two 50–60 min co-design workshops were conducted in February 2024 during existing community events. Each began with an introduction, informed consent, and structured activities delivered in Mandarin and English.

A pilot session with three older Chinese adults was held beforehand to refine materials for clarity and accessibility. Adjustments included larger print formats, sticker-based inputs, and simplified instructions.

The workshops followed a three-stage structure:

Stage 1: Daily routine mapping

Stage 2: Role and community mapping

Stage 3: Communication preferences

3.3.1. Stage 1: Daily Routine Mapping

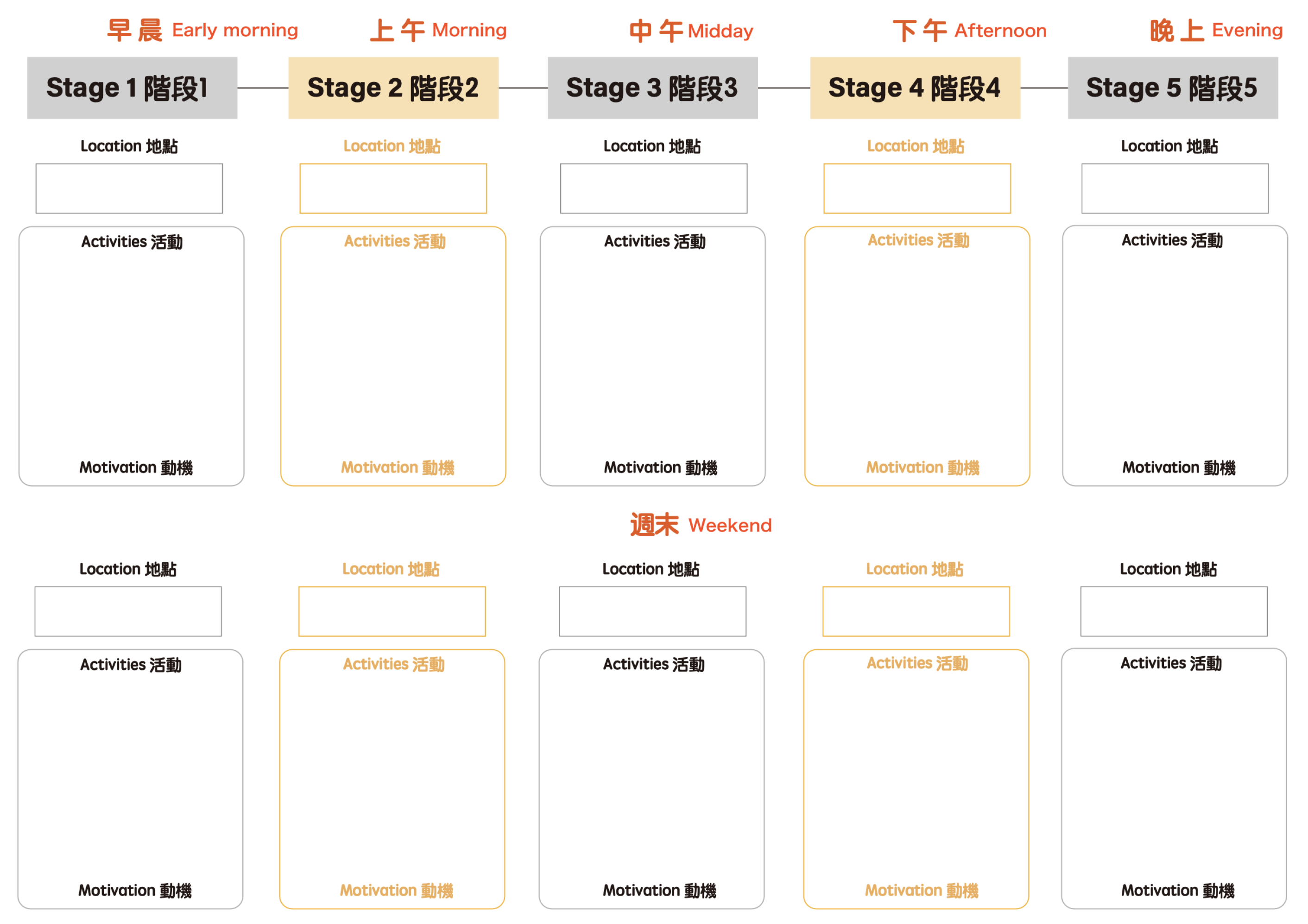

As shown in

Figure 1, a user journey mapping template was used to document participants’ weekday and weekend activities. The template captured daily routines across five time slots (early morning, morning, midday, afternoon, evening), along with corresponding locations, activities, and motivations.

3.3.2. Stage 2: Role and Community Mapping

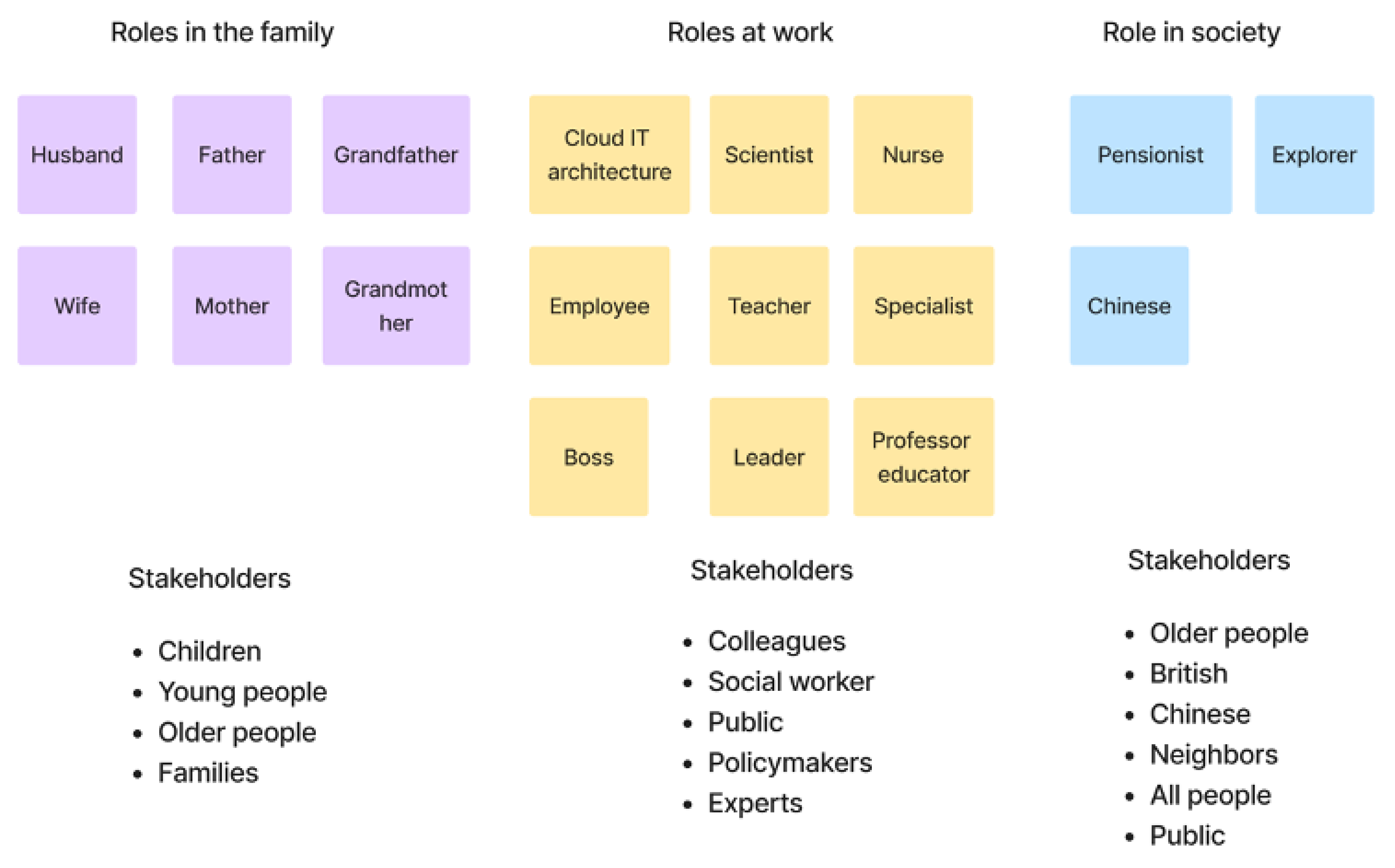

Figure 2 illustrates the worksheet used in Stage 2. Participants explored their personal values, identified key social roles, and mapped their communities. Cartoon stickers and written descriptions were used to represent identities, social networks, and beneficiaries of climate-related actions.

3.3.3. Stage 3: Communication Preferences

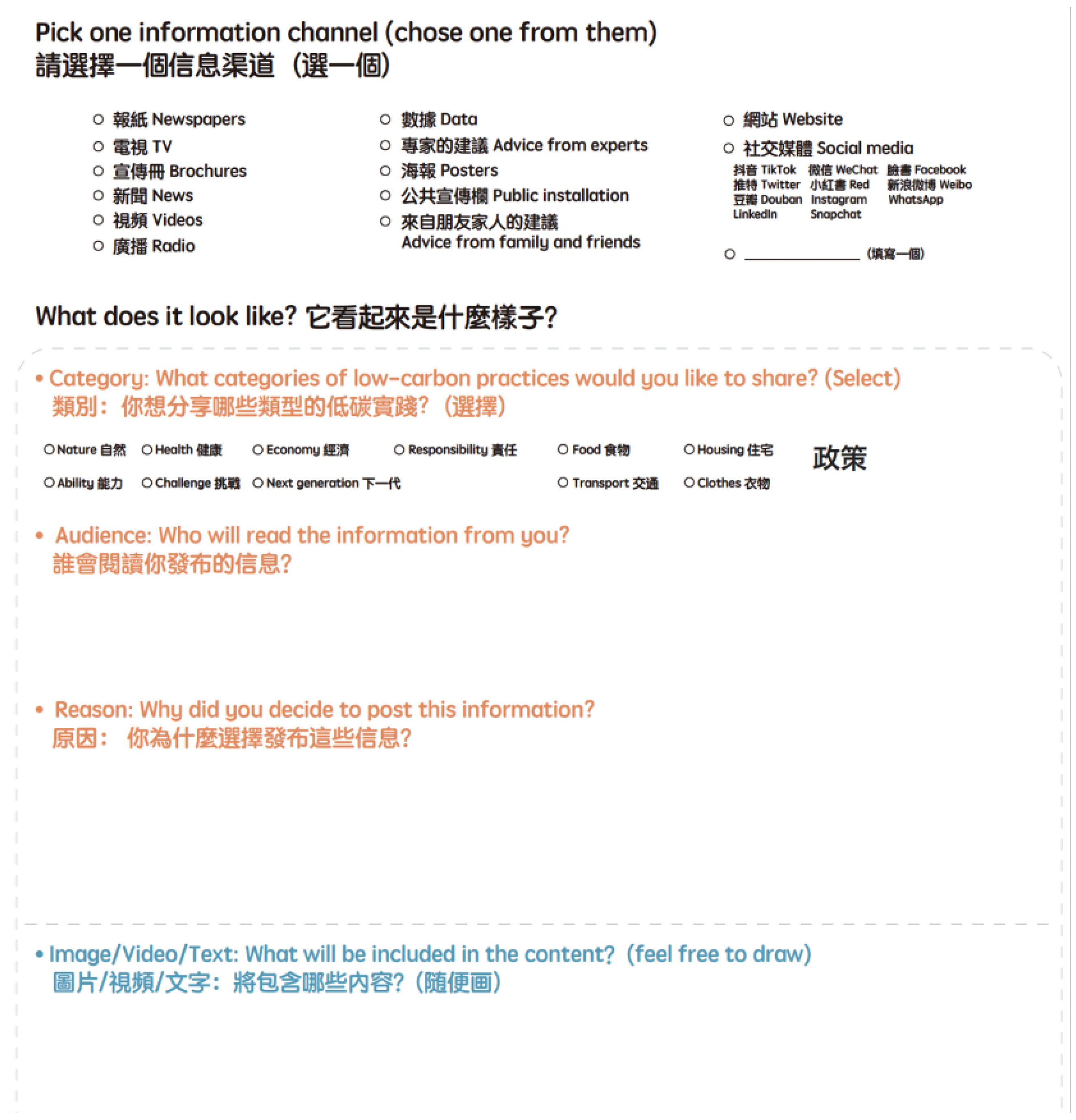

In Stage 3, participants completed a communication worksheet (

Figure 3) to identify preferred information sources, messages, and audiences. They selected trusted channels such as newspapers, WeChat, or face-to-face networks, and co-created climate messages customised for specific audiences.

Data collection involved completed worksheets, field notes, and photos of artefacts.

Table 2 outlines each task.

3.4. Workshop Visual Materials

All visual materials were designed to be bilingual, low-barrier, and engaging for older adult participants.

3.5. Data Saturation and Thematic Consistency

Following the first session, data richness and variation indicated sufficient coverage across key themes. Similar behavioural patterns emerged in the second session—especially regarding language-based information barriers and cultural motivations (e.g., thrift, family care). Participants with higher English proficiency engaged more with policy or text-based content, while others relied on images, interpersonal support, and Chinese-language media. These overlapping patterns suggest thematic saturation was reached within the small but diverse sample.

3.6. Data Analysis

All photos and completed worksheets were digitised and securely stored on a university-provided laptop. All responses were anonymised using alphanumeric codes (e.g., MEC01, NLC02) to maintain participant confidentiality.

3.6.1. Visual Analysis

Visual analysis was conducted to examine the climate-related illustrations created by participants during the workshops. The analysis was structured as follows:

Categorisation by theme and symbolism: Drawings were classified based on their thematic content or symbolic representation.

Interpretation of visual elements: Symbols and imagery were analysed alongside participants’ verbal explanations to identify underlying concepts and meanings.

Comparative analysis: Differences and similarities between participants’ drawings were examined. For example, repeated depictions of trees, flowers, and animals suggested a strong emotional connection to nature, while the frequent inclusion of mobile phones indicated a preference for digital media as a communication tool for climate-related information.

3.6.2. Thematic Analysis

A thematic analysis was performed on the open-ended responses collected through worksheets and discussions. The process involved:

Data transcription and organisation: Open-ended responses were transcribed and systematically categorised.

Coding of key concepts: Keywords such as “low-carbon behaviour,” “information sources,” and “motivations” were identified and coded.

Extraction of core themes: Overarching themes were synthesised from the data, including “concern for future generations” and “respect for nature”, which reflected participants’ motivations for engaging in climate action.

The user journey includes time sequences (daily activity schedules from morning to evening), activity categories (such as exercise, shopping, social interactions, religious practices, and work), social interactions (whether they involve family, friends, or the community), and motivational information (reasons for certain behaviours provided by participants).

In analysing the user journey, four analytical methods were used. The specific steps include frequency analysis, which identifies the most common activities and the most popular locations; thematic analysis, which summarises the low-carbon behavioural patterns of older migrants; narrative analysis, which examines the structure and changes in their daily routines; and social network analysis (SNA), which explores how they obtain information through communities, friends, and family.

3.6.3. Triangulation

To ensure the reliability and validity of the findings, a triangulation approach was employed. An independent review was conducted by a design assistant who participated in the workshops. The external perspective provided valuable insights.

3.6.4. Summary: Linking Method to Research Aims

Through a combination of narrative, visual, and thematic analysis—triangulated by an independent observer—this methodological approach enables a deep understanding of how older Chinese migrants perceive their climate roles and make sense of low-carbon behaviours. By mapping daily routines, social influences, and information preferences, the study surfaces how cultural identity and lived experience intersect with climate action. This empirical grounding is crucial for developing targeted, culturally resonant strategies for inclusive climate communication.

4. Results

The results and findings from the three stages of the workshop about the objectives will be explained in this section, including the key user journeys in the lives of older people, the roles they play in their lives, the value that these roles can provide, the choice of net-zero information channels, and the kind of information channel preferred.

4.1. “My Day”: The Intersection of Everyday Life and Sustainable Living Among Older Migrants

This section presents an analysis of the user journey data collected from older Chinese migrants, detailing their daily routines, motivations, and activity patterns on weekdays and weekends. The findings provide insights into their lifestyle habits, information consumption, and potential opportunities for integrating low-carbon behaviours.

4.1.1. Weekday–Weekend Contrasts: A Rhythmic Routine

The user journey data reveals a highly structured and domestically centered lifestyle among older Chinese migrants, especially during weekdays. Most participants spent the majority of their time at home, engaging in routine tasks such as cooking, cleaning, consuming media, and occasionally performing remote work. Physical exercise, particularly morning walks, tai chi, and stretching routines, was widespread, often gendered—women tended toward group-based activities, while men preferred gardening or solo exercise.

Weekend routines, in contrast, were markedly more mobile and social. Participants frequently visited family, attended religious or cultural gatherings, and engaged in shopping or leisure activities such as visiting parks or attending community events. Public transport and free senior bus passes supported these activities, reinforcing sustainable habits through structural accessibility.

Key insight: While weekdays offered predictable, low-mobility routines, weekends served as key touchpoints for social engagement and climate-related communication opportunities, especially in community and faith-based spaces.

4.1.2. Daily Patterns and Behavioural Touchpoints

Table 3 summarises the frequency of key activities across the week. Patterns suggest that sustainability was not necessarily a conscious pursuit, but emerged incidentally through cost-saving, convenience, or cultural norms.

Key insight:

Structured daily routines: Weekday activities are predominantly home-centered (N = 10), while weekends feature increased social interactions (N = 12) and outdoor mobility (N = 10).

High media engagement: Information is primarily accessed through traditional home-based media, such as television and newspapers (N = 14), underscoring their importance in climate communication.

Unconscious low-carbon behaviours: Actions like recycling, using public transport, or shopping at second-hand markets are common (N = 7), but are largely driven by frugality or practicality rather than explicit climate concern.

Culture and health as entry points: High engagement in cultural activities (N = 13) and regular physical exercise (N = 15) suggest that low-carbon messaging could be effectively introduced through cultural participation or health-oriented initiatives.

4.1.3. Media Habits and Trust Channels

Information access patterns reinforce the domestic and media-rich nature of weekday life. Television, newspapers, and social media—particularly WeChat—were the dominant channels. As summarised in

Table 4, participants differentiated sharply between entertainment, trusted knowledge, and sharable content, with traditional media often regarded as more authoritative, and social media as more accessible for peer sharing.

Key insight: Messaging targeting older Chinese migrants should balance familiarity and credibility—e.g., combining TV/radio-style content with social media distribution via trusted peer groups.

4.1.4. Everyday Sustainability: Implicit, Not Intentional

Though participants rarely used climate language, many engaged in behaviours aligned with sustainability, including:

Energy conservation (motivated by rising utility costs)

Public transit (due to free senior travel cards)

Food frugality (linked to cultural values)

Second-hand shopping/reuse (as thrifty practice)

These findings suggest that culturally rooted habits and economic rationality may be more effective frames for climate engagement than environmental urgency alone.

4.2. “Who Am I”: Intergenerational Roles, Social Identity, and Motivation

This section presents findings from Stage 2 of the co-design workshop, which explored how older Chinese migrants perceive their social roles and responsibilities, the communities they are embedded in, and their motivations for participating in climate-related actions. The results uncover how intergenerational values, cultural affiliation, and professional identity shape both climate awareness and communication behaviours.

4.2.1. Self-Perception and Core Values

Participants were asked to reflect on their strengths and roles within their families and communities. Responses revealed a deep sense of intergenerational duty, a continued engagement with professional expertise, and strong moral and caregiving values.

Key findings:

Family-oriented identities: Most participants described themselves as parents or grandparents, emphasising their role in nurturing younger generations.

Continued professionalism: Several participants identified with past or current professional roles (e.g., educators, researchers), suggesting an enduring sense of social contribution.

Caregiving and moral anchoring: Common strengths included patience, responsibility, and mentoring—values deeply tied to both family and civic duty.

These patterns are further detailed in

Table 5, which summarises the distribution of self-perceived strengths among participants.

These insights suggest that climate engagement strategies targeting this demographic should be grounded in family values, intergenerational continuity, and practical contribution.

4.2.2. Community Participation and Social Networks

To understand the everyday social environments of participants, we asked them to identify key communities in which they regularly participate. Findings show strong ties to cultural, religious, and professional networks.

Key findings:

Ethnic and cultural networks: Chinese community groups (N = 7) were highly cited as sources of both social support and information exchange.

Religious institutions: Faith-based communities (N = 4) played important roles in providing moral grounding and belonging.

Public and recreational spaces: Public parks and activity centres (N = 5) were frequented for health and leisure.

Professional circles: For those still working, professional engagement continued through universities, business, or social groups (N = 5).

Markets and shopping spaces: Shopping was viewed as a daily necessity and social touchpoint (N = 4).

These findings are further detailed in

Table 6, which summarises the distribution of participants’ social circles.

These results highlight the potential of community-based and culturally relevant spaces as trusted venues for climate communication and intervention.

4.2.3. Intended Beneficiaries of Climate Action

Participants were asked to reflect on who they believe would benefit from their engagement in low-carbon or climate-related behaviours.

Key findings:

Younger generations (N = 6): Children and grandchildren were the most frequently mentioned beneficiaries, reflecting a strong intergenerational motivation.

General public (N = 5): Some participants viewed their actions as contributing to broader social good and policy change.

Friends and neighbours (N = 4): Participants also considered their immediate social circles as part of the climate solution.

Industry and policymakers (N = 3): A few participants hoped their knowledge could influence decision-makers.

These findings are further summarised in

Table 7, which outlines the distribution of beneficiaries identified by participants.

Older Chinese migrants see themselves as valuable contributors to both family and society, driven by a strong sense of responsibility, caregiving, and lifelong learning. Their social participation is embedded in ethnic, religious, and professional networks, which serve as powerful entry points for climate engagement. Framing climate action through intergenerational benefit, cultural identity, and practical social roles could enhance message resonance and encourage active participation.

4.3. “How to Tell You”: Climate Messaging Preferences and Strategies

This section synthesises findings from Stage 3, exploring how older Chinese migrants prefer to communicate low-carbon information. The analysis focuses on four key aspects: trusted channels, motivations for sharing, preferred formats, and audience strategies. Visual illustrations and tables support the emerging patterns and communication preferences.

4.3.1. Trusted Channels: Between Familiarity and Credibility

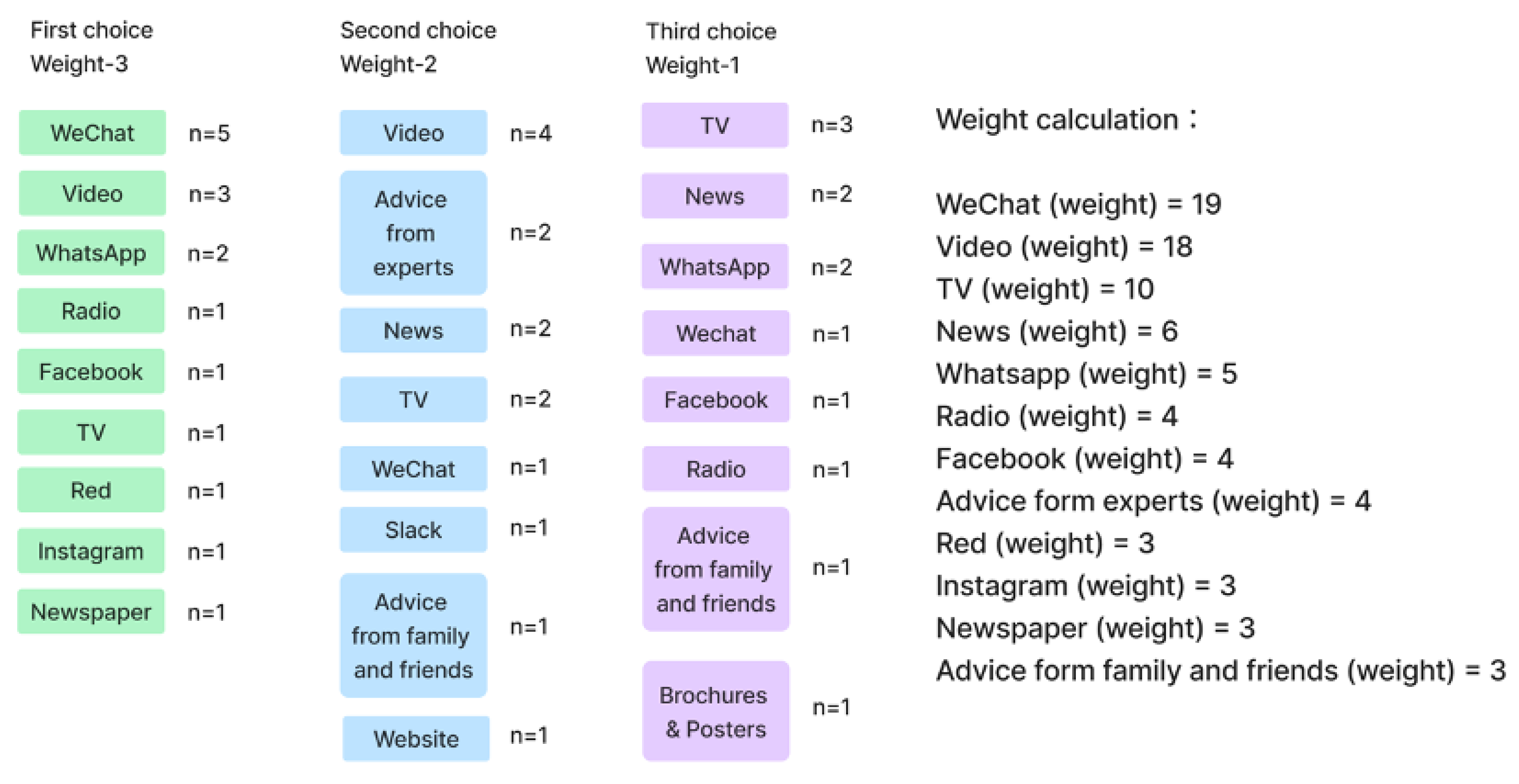

As shown in

Figure 4. Participants showed a clear preference for social media platforms—especially WeChat, followed by video-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube, Kuaishou), WhatsApp, and Facebook. These were valued for their ease of sharing, visual appeal, and reach within personal networks.

“I use WeChat every day; it’s convenient for sharing videos with friends and family.” (MEC05)

“Videos are intuitive and people comment more.” (NLC01)

At the same time, traditional media—such as Chinese-language TV programs and newspapers—remained important, especially for participants with lower digital literacy. Trust in official news and expert voices emerged as a key factor.

“I prefer expert advice rather than misleading social media posts.” (MEC03)

Key insight: A hybrid approach—combining social media’s reach with expert-backed credibility—is most effective.

4.3.2. Low-Carbon Topics of Interest

The participants expressed a strong interest in sharing practical, everyday sustainability practices, which they categorised into three broad areas:

Social concerns: Nature conservation, health, economic benefits, and societal responsibility.

Individual experiences: Personal ability to contribute, challenges faced, and reflections on intergenerational responsibility.

Lifestyle habits: Sustainable choices in food, housing, transportation, and clothing.

Key insights: These findings indicate that older Chinese migrants are most inclined to share low-carbon practices that are directly relevant to their everyday lives and economic realities. Climate messaging targeting this demographic should thus prioritise practical, relatable advice over abstract policy discussions.

4.3.3. Target Audience and Intended Impact

The most frequently cited audiences for climate-related messages were:

The next generation (children and grandchildren).

Peers, colleagues, and professional networks.

The general public and policymakers.

A strong intergenerational focus emerged in the discussions, with many participants expressing a desire to pass on sustainable habits to their children and grandchildren.

“I want my children and grandchildren to be more environmentally conscious. They should waste less food and use public transport more.” (MEC07)

“If I have a good experience, I would like to share it with more people, so that it benefits the next generation.” (MEC04)

Beyond family members, some participants mentioned their peers and social groups, particularly those who might be interested in adopting similar sustainable behaviours. A few also highlighted policymakers and professionals in their respective fields, indicating an awareness that individual actions should be complemented by systemic change.

“I’ve started using an electric car, and I’d like to persuade my colleagues to do the same. If everyone does a little, we can save our planet.” (MEC03)

4.3.4. Motivations for Sharing: Family, Responsibility, and Savings

Participants identified several motivations for sharing low-carbon information, with concern for the next generation and a sense of social responsibility being the most prominent reasons. Economic considerations, such as the benefits of saving energy and reducing costs, were also significant factors. Three primary motivations were identified (see

Table 8).

Key insight: Effective climate messaging should link intergenerational care with practical benefits.

4.3.5. Preferred Formats: Visual Storytelling over Text

To understand how participants visualised and structured climate-related information, participants were invited to create simple hand-drawn content or describe their ideal information formats. Since many participants were unfamiliar with hand-drawing, they either provided written descriptions or received assistance from the researcher to complete their visual representations.

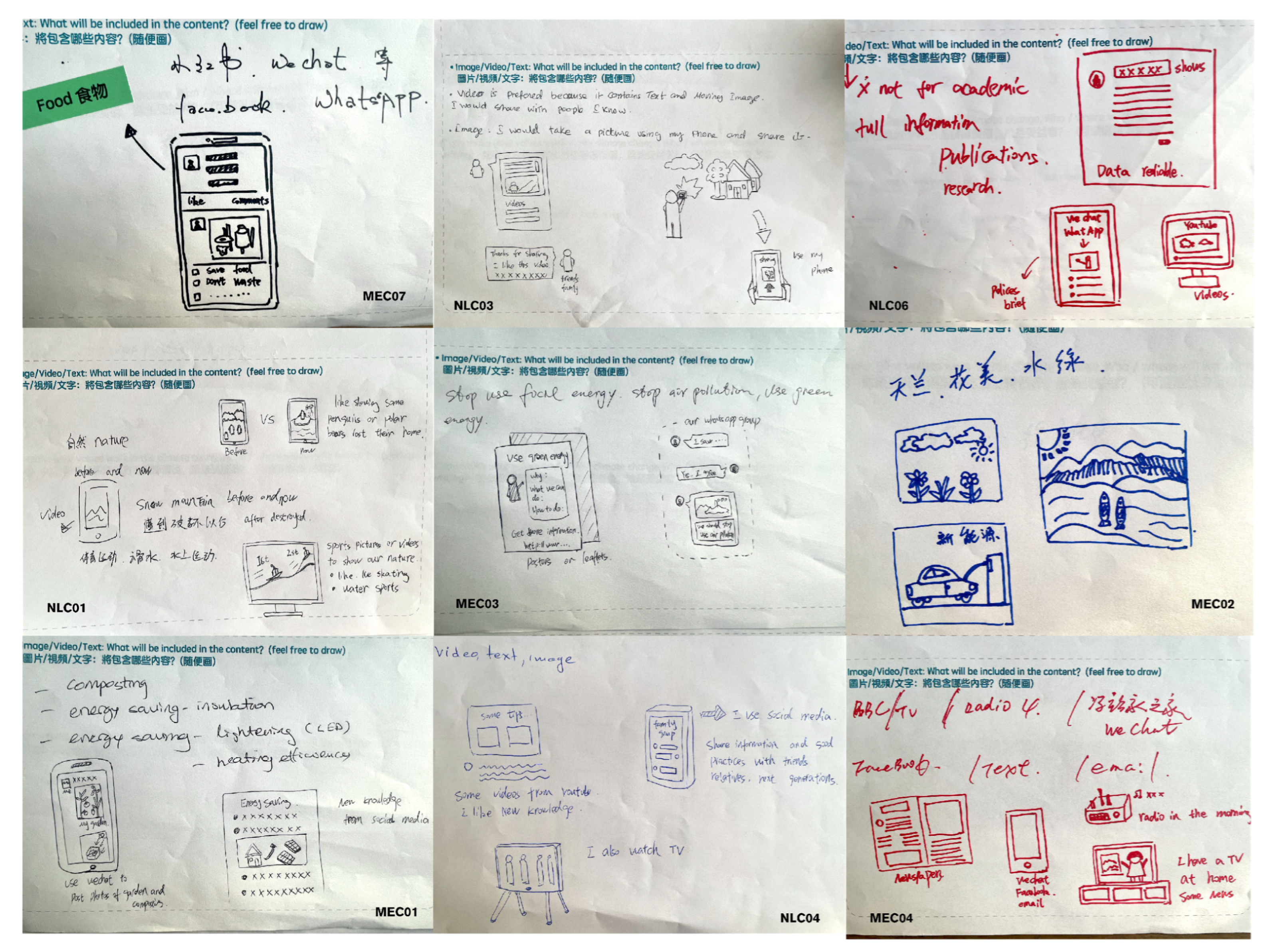

Figure 5 provides examples of participant-generated content, three key themes consistently emerged in the shared content:

Nature and environmental conservation—Participants used images of forests, clean air, mountains, and animals to express emotional connections to the environment and to highlight the urgency of ecological protection. “I want to share pictures about nature—snowy mountains, clean water, forests, and animals. If people see beautiful nature, they will want to protect it.” (NLC01)

Practical low-carbon practices—Visuals often included actions such as recycling, using electric vehicles, or conserving energy at home, linking climate behaviours to daily routines. “I recently switched to an electric car. If I can share my experience, maybe more people will follow. I think practical examples work better than slogans.” (MEC01)

Intergenerational responsibility—A recurring theme was educating children and grandchildren, reflecting a desire to pass on values and influence family sustainability choices. “I tried to educate my son-in-law about saving energy, but he believes we should enjoy life instead. There’s a big gap between generations in how we see sustainability.” (NLC02)

These drawings reflect the participants’ storytelling preferences, rooted in lived experience and visual communication. Rather than abstract or policy-driven messages, they favoured emotionally resonant, personally relevant narratives that are easy to understand and culturally grounded.

In terms of media format, the findings align with the visual preferences shown here:

Videos were valued for their ability to combine images, voice, and motion, enhancing engagement.

“Videos are easier to share and more interesting to watch. You can include text, images, and sound all at once.” (NLC03)

Images and infographics were preferred for their clarity, especially when language was a barrier.

“Images work better than text. If the audience is highly educated, then maybe text is fine.” (NLC05)

Text was regarded as less effective for general outreach, though still suitable for professional audiences.

“I read academic papers, so I would prefer well-researched text. But for general climate information, videos work better.” (NLC06)

For media platforms and dissemination channels, participants used both digital and traditional platforms, depending on familiarity, trust, and audience:

Social media (WeChat, version 8.0, Tencent, Shenzhen, China; WhatsApp, version 24.10, Meta Platforms, Menlo Park, CA, USA; Red, version 8.43, Xiaohongshu, Shanghai, China): Preferred for daily sharing with friends and family.

“I share things with my family on WeChat and Facebook. It’s easy, and people can comment and discuss.” (MEC05)

Traditional media (TV, newspapers, radio): Trusted by those with lower digital literacy.

“I trust the news more than social media. There’s too much misinformation online.” (MEC03)

Professional channels (workplace, formal reports): Used to reach educated peers or policymakers.

“If I want to reach policymakers, I would use academic papers or formal reports, not social media.” (NLC06)

These insights reinforce the importance of multimodal, audience-sensitive climate communication. While visual and interactive formats (especially videos and infographics) are ideal for general audiences, text-based materials remain effective in formal or expert contexts. Climate campaigns targeting older migrants should balance emotional storytelling with trustworthy sources, leveraging both peer networks and authoritative voices.

5. Discussion

This study used co-design workshops with older Chinese migrants in London-based community settings to investigate how they acquire and disseminate low-carbon and climate change information in their everyday lives. The findings highlight how participants’ daily activity patterns, social roles, and information preferences shape their engagement with sustainable behaviours and reveal key opportunities for intervention.

This section discusses the findings in relation to the study’s three research questions:

Sustainable routines (RQ1): In what ways do older Chinese migrants demonstrate sustainable behaviours through their daily routines?

Social roles and influence (RQ2): How do their social roles—particularly within the family—influence their understanding of and participation in low-carbon activities?

Information channels (RQ3a): Through which information channels do they engage with climate-related content?

Message formats (RQ3b): Which message formats do they perceive as most trustworthy and effective?

These questions are framed through Sense-making theory [

17], focusing on how participants construct identity, interpret social cues, and evaluate the plausibility of climate-related messaging.

The discussion is organised around key insights drawn from the three stages of the co-design workshops: (1) “My Day”: Everyday Life as a Foundation for Low-Carbon Practices; (2) “Who Am I”: Social Roles and Intergenerational Motivation; (3) “How to Tell You”: Climate Messaging Preferences and Strategies. These insights are then situated within the broader literature on ageing, migration, and design, followed by reflections on practical implications, study limitations, and directions for future research.

5.1. Key Findings

5.1.1. Everyday Routines as Entry Points for Climate Engagement (RQ1)

User journey mapping revealed a consistent weekly rhythm among older Chinese migrants that shaped their low-carbon behaviours. During weekdays, routines were largely home-based, while weekends involved broader social interactions such as visiting markets, temples, or community groups. This pattern aligns with ageing literature on spatial contraction and the tendency of older adults to rely on familiar, proximate environments [

55]. Rather than viewing this limited spatial range as a constraint, however, it may serve as a strategic foundation for designing place-based sustainability interventions that are embedded in everyday routines and trusted spaces.

Importantly, “external” spaces such as parks, churches, and Chinese community centres offer not only physical presence but also trusted social environments—ideal for informal climate messaging via posters, social chat groups, or health-related campaigns. These sites are underutilised assets in environmental communication.

Instead of treating older migrants as passive recipients, design should treat them as situated communicators with context-specific rhythms and motivations.

5.1.2. Family and Community Roles: The Dual Influence of Older Migrants (RQ2)

Participants’ roles as caregivers, mentors, and active community members deeply influenced their interpretation and practice of sustainability. This study identifies three primary domains in which older Chinese migrants enact their social roles: family, workplace, and wider society (see

Figure 6). Within families, participants emphasise educating and supporting the next generation, often prioritizing the needs of children and grandchildren. In professional contexts, they draw on lifelong expertise—serving as mentors, teachers, or business leaders—extending their influence beyond retirement. As community members, they focus on health, prudent planning, and thrift, often supporting cultural and faith-based organizations.

Notably, several participants recognized their impact not only within specific groups but also in the broader public sphere; some explicitly identified “all people” or “the public” as beneficiaries of their knowledge and action. This highlights a multi-layered sense of social responsibility, suggesting that older migrants view themselves as agents of change both within and beyond their immediate circles.

These findings echo established literature on intergenerational and communal ties [

24]. Unlike mainstream climate communication studies that focus primarily on youth or middle-class households, our results underscore the unique bridging function of older migrants. Through everyday acts—such as family meals, childcare, and community volunteering—they transmit values of thrift and resourcefulness to younger generations, while also serving as trusted leaders and organizers in their communities.

5.1.3. Information Channels: Navigating Digital and Traditional Media (RQ3a)

Participants engaged with climate-related information through both digital and traditional communication channels, reflecting a hybrid media environment in which accessibility and trust vary by context.

Digital platforms: WeChat was the most commonly used platform for exchanging messages, videos, and articles with family and peers. Video-based apps such as YouTube and TikTok (Kuaishou) were praised for their engaging, easy-to-follow formats.

Traditional media: Television, Chinese-language newspapers, and radio remained popular, particularly among participants less comfortable with digital tools. These were perceived as more credible than fragmented online content.

These media habits illustrate how older Chinese migrants shift between platforms depending on the nature of the content, their familiarity with the source, and perceived credibility. Such flexibility aligns with the theory of hybrid media communication [

56], which calls for multi-channel strategies in sustainability outreach.

5.1.4. Message Formats and Trust: Matching Preferences to Literacy and Context (RQ3b)

Participants expressed clear preferences regarding the format of climate information, revealing how literacy, personal habits, and emotional connection shape message effectiveness.

Visual and multimedia formats: Videos were overwhelmingly favoured due to their clarity, relatability, and ease of sharing. Participants described videos as more engaging and suitable for conveying complex topics like climate change.

Audience-specific content: Participants noted that format choices should be adapted based on the target audience. For those with lower educational levels or limited English proficiency, pictures and short videos were more appropriate. In contrast, those with higher literacy were more open to text-based content, including articles and research summaries.

These preferences reflect the role of cues in Sense-making theory—visual and narrative formats offer accessible entry points into sustainability concepts. Designing effective climate communication for older migrants thus requires alignment between content complexity and audience capacity, particularly when addressing under-represented or linguistically diverse communities.

5.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

5.2.1. Migration Studies and Social Networks

These findings echo existing literature emphasising the critical role of social networks and ethnic community identity in shaping the everyday behaviours of older migrants [

57,

58]. Distinct from the general older population, older Chinese migrants rely heavily on family bonds and intra-community connections, rather than on government or mainstream English-language information sources. Community activities and personal ties—rather than official or impersonal messaging—remain their most trusted channels for both daily life and sustainability information.

Importantly, this research also reveals that some participants wish to influence policymakers and the broader public. This reflects an emergent theme of “immigrant empowerment” [

59], where older migrants are not just passive recipients, but also become active producers and transmitters of knowledge, especially on issues such as sustainability and climate change. This highlights an untapped potential; leveraging community leaders and peer networks as “amplifiers” of low-carbon messaging within ethnic minority contexts. This supports calls for more community-driven, participatory approaches in sustainability interventions targeting migrant populations.

5.2.2. Co-Design in Environmental Contexts

The co-design approach used in this study supports arguments by Ceschin and Gaziulusoy that addressing sustainability challenges requires collaboration across stakeholders—including users themselves [

60,

61]. In our workshops, older Chinese migrants became not only research participants but also co-creators of knowledge and solutions. This participatory process not only produced first-hand insights for the research team, but also sparked new awareness and agency among participants. Many reported being previously unfamiliar with climate and net-zero concepts, but found them highly relatable when linked to daily routines and family values.

This suggests that co-design is not just a methodological choice but an empowerment tool. It gives voice to traditionally under-represented groups and fosters their practical engagement in sustainability. For policy and practice, our findings provide evidence for adopting culturally tailored, community-led strategies in climate interventions, especially when aiming to reach minority older adults.

5.2.3. Cultural Framing of Climate Motivation

Interestingly, none of the participants articulated climate concern through a nationalistic or state-aligned lens. Instead, motivations for sustainable behaviour tended to emerge from personal habit, family responsibility, or health-related reasoning. This contrasts with findings from studies within China that attribute climate engagement to national identity or state-led campaigns. The diaspora context, generational background, and limited exposure to domestic media campaigns may explain this difference.

Furthermore, while this study focuses solely on older Chinese migrants, several findings point to culturally specific values—such as thrift, filial responsibility, and intergenerational support—that align with Confucian traditions [

62]. These values contrast with more individualistic, autonomy-focused ageing norms commonly discussed in Western contexts [

63]. While this study did not include a comparative Western sample, the emphasis on family-based sustainability and communal decision-making reflects a collectivist ethos not always present in non-migrant or Western elder populations. This highlights the need for future cross-cultural work comparing migrant and non-migrant seniors’ motivations and interpretations of climate action.

5.2.4. Unintentional vs. Intentional Sustainability

A critical distinction emerged between participants’ deliberate engagement with climate topics (e.g., attending workshops or watching educational videos) and their habitual practices that nonetheless support sustainability—such as reusing containers, conserving electricity, or avoiding food waste. These behaviours were often motivated by economic prudence or cultural upbringing rather than environmental awareness [

64,

65]. This latent form of sustainability highlights the importance of recognising diverse motivations behind climate-positive actions, especially within older migrant groups. It also suggests that future communication strategies might benefit from acknowledging and validating these habitual, culturally-rooted practices, instead of solely focusing on overt environmental messaging [

66,

67,

68].

5.3. Future Work and Potential Interventions

Building upon the study’s insights into daily practices, social roles, and media preferences, this section outlines future directions for design research and climate communication targeting older migrant populations. The following intervention pathways aim to enhance cultural relevance, agency, and accessibility in promoting low-carbon behaviours.

5.3.1. Community-Centred Approaches

Trusted everyday spaces: Religious venues and Chinese community centres should be leveraged as climate engagement hubs. Their high credibility and routine use make them ideal platforms for hosting workshops, storytelling events, or health-themed climate interventions.

Household-based design: Playful or gamified tools could be introduced at home to encourage shared sustainability goals. This supports intergenerational dialogue and reframes low-carbon action as a form of care and cultural continuity.

These approaches position the household and community as critical “climate touchpoints,” especially for culturally grounded communication.

5.3.2. Mixed-Media Messaging Strategies

Hybrid media campaigns: Given participants’ use of both WeChat and traditional Chinese-language media, future outreach should embrace “hybrid dissemination models.” This ensures inclusivity across digital literacy levels and builds trust via familiar platforms.

Visual and multilingual storytelling: Videos, infographics, and narratives in simplified Chinese (with Mandarin or Cantonese subtitles) should be prioritised to overcome linguistic barriers and enhance emotional resonance.

This reinforces the value of culturally tailored design in expanding access to sustainability information.

5.3.3. Intergenerational Collaboration

Skills exchange models: Pilot programs could test intergenerational pairings, where older adults share practical wisdom and cultural values, while younger family members assist with technology and media use. This promotes mutual learning and collective action.

Cross-generational co-design: Co-design workshops that include both generations can generate creative, family-centred sustainability interventions rooted in shared cultural identity.

Such collaboration bridges generational divides and embeds climate action within family dynamics and legacy values.

5.3.4. Advocacy and Policy Integration

Civic partnerships: Collaborations with councils or NGOs can support the development of linguistically appropriate resources and public events tailored to the older Chinese migrant demographic.

Migrant-led storytelling for policy influence: Future projects may empower participants as storytellers and advocates by creating avenues for dialogue with decision-makers and media. Their lived experiences can inform more inclusive climate policy and outreach strategies.

This recognizes older migrants as agents of change rather than passive recipients—a crucial shift in environmental communication.

5.4. Research Limitations

While this study yielded rich and nuanced findings, several limitations should be acknowledged when considering the broader application of the results. These relate to sample representativeness, socio-demographic diversity, and cultural-linguistic dynamics, which may affect the generalisability and interpretability of the findings.

1. Sample representativeness: Participants were primarily recruited from two Chinese community organisations in London. While these settings offered valuable access to older Chinese migrants, the sample may not fully reflect the diversity of this population across the UK or globally. Migrants in other regions, or with different migration pathways, dialect backgrounds, or settlement histories, may engage with climate information in distinct ways.

2. Socio-demographic variation: The sample included individuals with relatively high levels of social participation and Mandarin/English proficiency. Older adults with limited education, mobility, or language ability—particularly those experiencing social isolation—may face additional barriers to engaging with climate communication, which were not fully captured in this study.

3. Cultural and linguistic constraints: Although the workshops were delivered bilingually in Mandarin and English, participants who primarily speak other dialects (e.g., Hakka, Shanghainese, or regional Cantonese) may have experienced reduced comprehension. Additionally, cultural norms such as deference, politeness, or reluctance to disagree publicly may have limited critical feedback or open discussion during group sessions. These factors could have influenced how participants interpreted tasks or expressed their views.

Future research could benefit from including a wider range of geographic regions, dialect groups, and social backgrounds. Employing mixed-method designs—such as ethnographic fieldwork, one-on-one interviews, or longitudinal tracking—may help uncover more nuanced perspectives and reduce potential barriers linked to language or cultural norms.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses a critical gap in climate communication research by centring on older Chinese migrants—an often-overlooked population in both sustainability discourse and ageing studies. Through co-design workshops, we identified how culturally grounded values, such as thrift and intergenerational responsibility, shape sustainable practices embedded in participants’ everyday routines, social roles, and communication preferences.

Rather than viewing these individuals as passive recipients of climate messaging, our findings position them as active agents who navigate hybrid media environments and influence familial and community behaviours. Their climate actions are often driven by pragmatic and relational motives—such as health, habit, and care-giving—rather than formal environmental agendas or nationalist appeals.

These insights underscore the importance of inclusive, peer-led, and culturally responsive communication strategies. Designing effective interventions requires attention not only to content and format, but also to the linguistic, social, and emotional landscapes in which older migrants operate.

While the study’s scope was limited to two organisations in London, the findings provide transferable implications for other migrant contexts. Future research would benefit from cross-cultural comparisons with Western seniors, exploration of under-represented dialect groups, and intergenerational design approaches that build on the relational strengths of older migrants in climate action.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.N. and H.D.; methodology, Q.N., H.D. and A.K.; validation, A.K. and H.D.; formal analysis, Q.N. and H.D.; investigation, Q.N.; resources, Q.N.; data curation, Q.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.N.; writing—review and editing, H.D. and A.K.; visualization, Q.N.; supervision, H.D. and A.K.; project administration, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Brunel University London (protocol code 2023-48594-1 and date of approval: 18 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data relating to this study can be obtained from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shahzad, S.; Faheem, M.; Muqeet, H.A.; Waseem, M. Charting the UK’s path to net zero emissions by 2050: Challenges, strategies, and future directions. IET Smart Grid 2024, 7, 716–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, K.A.; Nolte, J.; Tillema Cope, M. Promoting climate change activism among older people. Generations 2022, 46, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Li, J.; Mao, W.; Chi, I. Exploration of social exclusion among older Chinese immigrants in the USA. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maller, C.; Strengers, Y. Resurrecting Sustainable Practices: Using memories of the past to intervene in the future. In Social Practices, Intervention and Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Elderly Chinese migrants, intergenerational reciprocity, and quality of life. N. Z. Sociol. 2014, 29, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, P. Family Value Matters: Intergenerational Solidarity and Life Satisfaction of Chinese Older Migrants. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Fokkema, T.; Wang, R.; Dury, S.; De Donder, L. ‘It’s like a double-edged sword’: Understanding Confucianism’s role in activity participation among first-generation older Chinese migrants in the Netherlands and Belgium. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2021, 36, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caidi, N.; Du, J.T.; Li, L.; Shen, J.M.; Sun, Q. Immigrating after 60: Information experiences of older Chinese migrants to Australia and Canada. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; AlSwayied, G.; Frost, R.; Rait, G.; Burns, F. Barriers and facilitators to health-care access by older Chinese migrants in high-income countries: A mixed-methods systematic review. Ageing Soc. 2025, 45, 1355–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, K.; Luebke, M. Expanding the engagement of older persons in climate change action. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, J.; Ali, S.A.; Tilstra, M.H.; Tiwari, I.; Nielsen, C.C.; Whitfield, K.; Jones, A.; Vargas, A.O.; Bulut, O.; Yamamoto, S.S. Listening to older adults’ perspectives on climate change: Focus group study. Int. Health Trends Perspect. 2022, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, I. An introduction to co-design. Sydney: Knode 2012, 12, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Latulippe, K.; Hamel, C.; Giroux, D. Co-design to support the development of inclusive eHealth tools for caregivers of functionally dependent older persons: Social justice design. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibbin, J.; Peng, F.; Hope, C. We want to play too: Co-design of a public intergenerational play space and service for improved mental health for older adults in the Australian Capital Territory. In Design for Dementia, Mental Health and Wellbeing; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Chang, F.; Gu, Z.; Kasraian, D.; van Wesemael, P.J. Co-designing community-level integral interventions for active ageing: A systematic review from the lens of community-based participatory research. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terkelsen, A.S.; Wester, C.T.; Gulis, G.; Jespersen, J.; Andersen, P.T. Co-Creation and co-production of health promoting activities addressing older people—A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weick, K.E.; Weick, K.E. Sense-Making in Organizations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S.P. Climate change and political (in) action: An intergenerational epistemic divide? Sustain. Environ. 2021, 7, 1951509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.N.; Singh, A.; Brumby, D.P. I Just Don’t Quite Fit In: How People of Colour Participate in Online and Offline Climate Activism. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 8, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neas, S.; Ward, A.; Bowman, B. Young people’s climate activism: A review of the literature. Front. Political Sci. 2022, 4, 940876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, E. “Nothing About Us Without Us”—The Barriers and Enablers of Persons with Disabilities as Climate Change Agents. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L.; Roy, S.; Aloni, O.; Keating, N. A scoping review of research on older people and intergenerational relations in the context of climate change. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormoș, V.C. The processes of adaptation, assimilation and integration in the country of migration: A psychosocial perspective on place identity changes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Lin, X. Migration of Chinese consumption values: Traditions, modernization, and cultural renaissance. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, A. Ethics and Perspectives of Sustainable Consumption Perspectives of Sustainable Consumption. In Ethical Approaches to Marketing: Positive Contributions to Society; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany, 2021; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhan, C. Best Practices in Sustainable Communication for Minority Communities. 2024. Available at SSRN 4946143. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4946143 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Lapinski, M.K.; Oetzel, J.G. Cultural tailoring of environmental communication interventions. In The Handbook of International Trends in Environmental Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 248–267. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, R. Traditional storytelling: An effective Indigenous research methodology and its implications for environmental research. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2018, 14, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, M.; Dietz, G. Difference in diversity: Multiple perspectives on multicultural, intercultural, and transcultural conceptual complexities. J. Multicult. Discourses 2015, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerder, D. ‘A Genuine Respect for the People’: The Columbia University Scholars’ Transcultural Approach to Migrants. J. Migr. Hist. 2015, 1, 136–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D.V.; Duong, L.H.; Truong, T.T.K.; Nguyen, N.T. Destination responses to COVID-19 waves: Is “Green Zone” initiative a holy grail for tourism recovery? Sustainability 2022, 14, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello-Frosch, R.; Zuk, M.; Jerrett, M.; Shamasunder, B.; Kyle, A.D. Understanding the cumulative impacts of inequalities in environmental health: Implications for policy. Health Aff. 2011, 30, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). Climate Change and Population Ageing in Asia-Pacific Region: Status, Challenges and Opportunities. 2022. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/kp/2022/climate-change-and-population-ageing-asia-pacific-region-status-challenges-and (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Collins, S.E.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Stanton, J.; Straits, K.J.; Gil-Kashiwabara, E.; Rodriguez Espinosa, P.; Nicasio, A.V.; Andrasik, M.P.; Hawes, S.M.; Miller, K.A.; et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; Dilling, L. Communicating change science. In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2011; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Head, L.; Klocker, N.; Dun, O.; Waitt, G.; Goodall, H.; Aguirre-Bielschowsky, I.; Gopal, A.; Kerr, S.M.; Nowroozipour, F.; Spaven, T.; et al. Barriers to and enablers of sustainable practices: Insights from ethnic minority migrants. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, L.; Klocker, N.; Aguirre-Bielschowsky, I. Environmental values, knowledge and behaviour: Contributions of an emergent literature on the role of ethnicity and migration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 43, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, M.J.; Stycos, J.M. Immigrant environmental behaviors in New York city. Soc. Sci. Q. 2002, 83, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.S.; Shandas, V.; Pendleton, N. The effects of historical housing policies on resident exposure to intra-urban heat: A study of 108 US urban areas. Climate 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, S.; Longo, D.; Zanobini, P.; Lorini, C.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Baccini, M.; Cecchi, F. How to communicate with older adults about climate change: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1347935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Bekerian, D.; Osback, C. Navigating the Digital Landscape: Challenges and Barriers to Effective Information Use on the Internet. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1665–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Shizha, E.; Makwarimba, E.; Spitzer, D.; Khalema, E.N.; Nsaliwa, C.D. Challenges and barriers to services for immigrant seniors in Canada: “You are among others but you feel alone”. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2011, 7, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosen, L.J.; Klöckner, C.A.; Swim, J.K. Visual art as a way to communicate climate change: A psychological perspective on climate change–related art. World Art 2018, 8, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, Q.; Ding, X.; Chen, C.; Wang, L. Detecting local opinion leader in semantic social networks: A community-based approach. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 858225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theall, K.P.; Fleckman, J.; Jacobs, M. Impact of a community popular opinion leader intervention among African American adults in a southeastern United States community. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2015, 27, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Cartano, D.G. Methods of measuring opinion leadership. Public Opin. Q. 1962, 26, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayetano, C. Dialogic Cultural Relationships of Expertise, Knowledge,(Inter) dependence and Power Within the Acculturating Family: Exploring the Technolinguistic Brokering Experiences of Adolescents and Their Immigrant Non-English Speaking Mothers. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, lTempe, AZ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tyyskä, V. Communication brokering in immigrant families: Avenues for new research. In Gender Roles in Immigrant Families; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Yu, H. WeChat and the Chinese Diaspora: Digital Transnationalism in the Era of China’s Rise; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. Chinese-Language Internet-Based Media Consumption of Chinese People in the UK and Their Intercultural Adaptation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, S.G.; Davies, A.R. SHARE IT: Co-designing a sustainability impact assessment framework for urban food sharing initiatives. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 79, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillan, M.; Costa, F.; Caiola, V. How could people and communities contribute to the energy transition? Conceptual maps to inform, orient, and inspire design actions and education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, T.; Fletcher, C. Sense-making: A complexity perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Marston, H.R.; Kazak, J.K.; Buffel, T. Ten questions concerning age-friendly cities and communities and the built environment. Build. Environ. 2021, 199, 107922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manovich, L. Understanding hybrid media. In Animated Paintings; Hertz, Ed.; San Diego Museum of Art: San Diego, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burholt, V.; Dobbs, C.; Victor, C. Transnational relationships and cultural identity of older migrants. GeroPsych 2016, 29, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göttler, A. Ethnic belonging, traditional cultures and intercultural access: The discursive construction of older immigrants’ ethnicity and culture. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2023, 49, 2290–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, A.; Buckingham, S.; Fedi, A.; Gattino, S.; Rochira, A.; Altal, D.; Mannarini, T. Resilience and empowerment in immigrant experiences: A look through the transconceptual model of empowerment and resilience. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2022, 92, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselova, E.; Gaziulusoy, İ. Bioinclusive collaborative and participatory design: A conceptual framework and a research agenda. Des. Cult. 2022, 14, 149–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Chan, A.C. Filial piety and psychological well-being in well older Chinese. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, P262–P269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, M.S.; Fiske, S.T. Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southerton, D.; McMeekin, A.; Evans, D. International Review of Behaviour Change Initiatives; The Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2011.

- Spaargaren, G. Theories of practices: Agency, technology, and culture: Exploring the relevance of practice theories for the governance of sustainable consumption practices in the new world-order. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

User journey mapping template used in Stage 1 (labels translated from Chinese). Participants marked their daily activities and motivations across five time periods.

Figure 1.

User journey mapping template used in Stage 1 (labels translated from Chinese). Participants marked their daily activities and motivations across five time periods.

Figure 2.

Visual worksheet used in Stage 2 (labels translated from Chinese). Participants explored personal and social roles using stickers and descriptions to represent their identities and networks.

Figure 2.

Visual worksheet used in Stage 2 (labels translated from Chinese). Participants explored personal and social roles using stickers and descriptions to represent their identities and networks.

Figure 3.

Communication worksheet from Stage 3 (labels translated from Chinese). Participants selected and customised preferred channels, messages, and audience types.

Figure 3.

Communication worksheet from Stage 3 (labels translated from Chinese). Participants selected and customised preferred channels, messages, and audience types.

Figure 4.

Information Channel Choice Ranking Map.

Figure 4.

Information Channel Choice Ranking Map.

Figure 5.

Examples of participant-generated hand-drawn communication materials from Stage 3, created with the assistance of a facilitator. Minor overlaps and incomplete text are present but do not affect the interpretation of the figure. Note. Drawings illustrate participants’ use of social media (WeChat, WhatsApp, Facebook), environmental symbols (trees, rivers), slogans (“Stop using fossil energy”), and traditional media (TV, radio).

Figure 5.

Examples of participant-generated hand-drawn communication materials from Stage 3, created with the assistance of a facilitator. Minor overlaps and incomplete text are present but do not affect the interpretation of the figure. Note. Drawings illustrate participants’ use of social media (WeChat, WhatsApp, Facebook), environmental symbols (trees, rivers), slogans (“Stop using fossil energy”), and traditional media (TV, radio).

Figure 6.

Role and Stakeholders Map.

Figure 6.

Role and Stakeholders Map.

Table 1.

Participant Information Form (N = 13).

Table 1.

Participant Information Form (N = 13).

| Participant Code | Job Role | Gender | Workshop Group |

|---|

| MEC01 | Retired employee | Male | 1 |

| MEC02 | Retired employee | Male | 1 |

| MEC03 | University teacher | Female | 1 |

| MEC04 | Nurse | Female | 1 |

| MEC05 | Dancer | Female | 1 |

| MEC06 | Chinese language teacher | Female | 1 |

| MEC07 | Media worker | Female | 1 |

| NLC01 | University teacher | Male | 2 |

| NLC02 | Retired preschool teacher | Female | 2 |

| NLC03 | Architect | Male | 2 |

| NLC04 | Housewife | Female | 2 |

| NLC05 | Business operator | Male | 2 |

| NLC06 | University teacher | Male | 2 |

Table 2.

Workshop Structure and Activities.

Table 2.

Workshop Structure and Activities.

| Stage/Task | Objective | Timescale | Justification |