1. Introduction

The concept of risk-taking in decision-making explores how individuals approach decisions involving uncertain outcomes. It is a construct complex because, in the literature, it is still unclear whether risk-taking behavior can be described as a stable trait or if it fluctuates based on situational factors [

1]. The central question is whether risk-taking is a trait-like construct, so it can be conceptualized as a stable characteristic across time and situations, or it is a state-like construct, i.e., a temporary condition influenced by context, emotions, or external factors. In this paper, we proposed that risk-taking in decision-making may change based on the situation; factors like the magnitude of potential losses or gains, social influence, and emotional states can shape how individuals evaluate risk at any given moment.

In everyday life, people often must make decisions in situations of risk in which the probability of gains or loss related to their choice is explicitly defined and/or known [

2]. Consequently, decision-making under risk is a crucial process for undertaking health behaviors [

3]. Unhealthy or risk behaviors include substance use, risky sex, drunk driving, and junk food, and the health impact of these behaviors during adolescence is well recognized [

4]. However, decision-making under risk is a process that occurs across the lifespan, and it has also been demonstrated that aging is associated with changes in decision behaviors [

5]. Hence, decision-making under risk can be influenced by both individual differences and life-span changes.

1.1. Individual Differences in Decision-Making Under Risk

With reference to individual differences, previous studies have shown that risk propensity influences how people make real-life decisions such as in the health environment [

6,

7]. Risk propensity can be conceptualized as an individual attitude to be attracted to potentially risky activities, behaviors, or choices [

8,

9]. Overall, people with a strong risk propensity tend to make decisions with both high potential benefits and high potential adverse consequences, whereas people with a weak risk propensity tend to be more cautious in decision-making [

1,

10].

Moreover, in the literature, risk propensity was found to be linked to sensation-seeking, but these two constructs are different [

11,

12]. Sensation-seeking has been defined as the “need for varied, novel, and complex sensations and experiences and the willingness to take physical and social risks for the sake of such experiences” [

13]. Both sensation-seeking and risk propensity influence decision-making, but there are differences in the focus of people’s choices. Precisely, risk-takers are focused on risky behaviors and hope to obtain positive outcomes from these behaviors and choices, whereas sensation-seekers are focused on novelty and underestimate the potential threat involved in novel activities and choices [

13].

In addition to risk propensity and sensation-seeking, other individual factors can impact the decision-making under risk; for example, self-conscious emotions shape how individuals perceive and evaluate risks [

14,

15]. Guilt, shame, and pride are categorized as self-conscious emotions [

16] and they are crucial to determine, adjust, replicate, accentuate, or extinguish thoughts and actions related to situational changes [

17]. By studying emotional differences, researchers can better predict how different individuals might react to similar risks. For example, some studies have found that experiencing shame is positively correlated with various unhealthy and risky behaviors, whereas guilt is negatively associated with these behaviors [

18]. Incorporating emotional responses into risk measurement can lead to a more accurate understanding of decision-making under risk, especially in areas like health, where emotion-driven decisions are prevalent.

Risk propensity, sensation-seeking, and self-conscious emotions such as shame and guilt interrelate to shape decision-making under risk by influencing both the motivation and regulation of risky behavior [

17,

18]. People high in risk propensity are more inclined to engage in risky choices, often driven by a desire for reward or novelty, which overlaps with sensation-seeking, a trait characterized by the pursuit of intense and novel experiences [

13]. However, self-conscious emotions act as internal regulatory mechanisms that may moderate these tendencies. For example, guilt can promote risk-aversion by prompting individuals to consider the potential negative consequences of their actions on others, whereas diminished shame or guilt sensitivity may exacerbate risk-taking, particularly in sensation-seekers [

16]. Thus, decision-making under risk emerges from a dynamic balance between impulsive drives for stimulation and emotional mechanisms that encourage self-regulation and social accountability.

1.2. Life-Span Changes in Decision-Making Under Risk

With reference to life-span changes, evidence about the age effect on decision-making under risk is controversial [

19]. Some studies have shown that risk preferences decrease with age, whereas other research has demonstrated that these do not change with age [

5,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Conversely, recent studies have found that emerging adulthood (i.e., 19–29 years of age) is associated with an increase in risk preference [

24,

25]. A meta-analysis has indicated that older adults can make advantageous decisions under risk and avoid risky behaviors compared to younger adults when information about the consequences of their choices is known [

26].

Other findings go against the hypotheses that risky decisions decline with age. It was found that the risk preferences of older and younger adults did not differ significantly in a decision-making task when both options were risky [

27]. Similarly, a study has shown that older adults’ risky decisions are comparable to those of younger adults, suggesting no age differences in decision-making under risk [

5]. Moreover, due to neurological and cognitive decline, it has been assumed that older adults would be more inclined to make risky decisions and to choose risky behaviors than younger adults. In this direction, some studies have indicated that older adults make more risky decisions in the health domain than younger adults [

28,

29] and they perceive themselves as less risk-seeking during the use of internet [

30].

Therefore, the decision-making literature suggests that findings about the aging effect on decision-making under risk are mixed and that the age effect has been poorly investigated in adulthood and aging rather than in early and adolescent development. In addition, although the influence of individual differences on decision-making under risk has been widely examined, there is no clear consensus yet as to how to explain these relations considering both younger and older adults.

1.3. The Present Study

To provide a contribution to this gap in the literature, the main aim of this cross-sectional study was to examine age differences in decision-making under risk, risk propensity, sensation-seeking, and self-conscious emotions between young and older adults. The novel perspective that this preliminary study brought to the field on decision-making under risk was whether risk-taking behavior can be described as a stable trait or if it fluctuates based on situational factors. Thus, we propose that risk-taking in decision-making may change based on the situation in which people make decisions (i.e., different domains: financial, risky sports, disinhibition, unconventional lifestyle) and on self-conscious emotions that people experience and their age. Due to this perspective, in a preliminary study we used both self-report questionnaires measuring risk propensity, sensation-seeking, and self-conscious emotions and a behavioral task on decision-making, because self-reported risk preferences can sometimes diverge from actual behavior. We also examined these constructs considering the age of the participants. As stated above, we compared young and older adults.

Consistent with recent studies, older adults were assumed to show comparable risk preferences to younger adults. In accordance with previous studies on sensation-seeking and self-conscious emotions, age differences related to different domains were hypothesized.

The first hypothesis that older adults show comparable risk preferences to younger adults was supported by recent research suggesting that while cognitive aging may affect decision-making processes, the overall risk preference could remain relatively stable across the lifespan. Studies indicated that age-related differences in risk-taking were often domain-specific rather than general, with older adults potentially showing similar or even greater risk tolerance in certain areas, such as social or health-related decisions.

The assumption of age-related differences in sensation-seeking and self-conscious emotions across domains is supported by evidence that sensation-seeking tends to decline with age due to changes in neurobiological reward sensitivity. In contrast, self-conscious emotions such as guilt and shame may become more pronounced or better regulated in older adulthood due to greater life experience and emotional maturity. Thus, age differences in risk-related behavior were hypothesized to vary depending on the domain of sensation-seeking, reflecting differential patterns in the interplay of sensation-seeking traits and emotional regulation across the lifespan.

Although this study was a preliminary study aimed at collecting data to facilitate the planning and execution of a larger experimental study, it may have some applications. Firstly, understanding one’s risk preferences can help people to make more informed decisions that align with their values and long-term goals. Secondly, understanding the risk attitudes of leaders or teams is crucial for strategic decisions, such as investments, innovation, or crisis management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The present research is a preliminary/pilot study aiming to collect data to facilitate the planning and execution of a larger experimental study on decision-making under risk. An approach to justifying the sample size is to use and reference one of the multiple pilot study sample size flat rules of thumb proposed [

31]. A flat rule of thumb is a single number that is suggested for the pilot study for all scenarios. For a continuous outcome, a sample size of anywhere from 12 per group to 35 per group has been proposed [

31]. For all these reasons, in the present study, we used a sample of 20 per group as the stopping point for subject collection.

A total of 40 subjects (20 young adults and 20 older adults) participated in the present study. The young adults were aged 18–35 years (M = 23.25, SD = 2.59). The older adults were aged 65–70 years (M = 68.50, SD = 4.01). All the participants were healthy with no neurological or psychiatric diseases and the majority of them had a socioeconomic status included in the middle-class category.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the two groups.

The sample were recruited through flyers placed in universities and social venues, as well as social-media pages. Interested subjects were informed to contact the study by phone or e-mail to complete a screening to determine eligibility. The screening involved a 60 min clinical interview conducted by a psychologist in a room of an Italian University. During the screening, participants were asked demographic and psychiatric questions to gather information about their health condition and socioeconomic status and to determine their eligibility for the study.

Inclusion criteria: no history of neurological disorders or head trauma, no history of a psychological or psychiatric disorder or illness, no history of learning disabilities, no history of intellectual or neurological disabilities, no experience with risk-taking tasks, Italian nationality, 18–70 years of age. Exclusion criteria: current pharmacological treatments, professional extreme sports athletes, smoking at least 10 or 20 cigarettes per day for the past six months, drinking at least one strong drink per day for the past six months, having received at least two speeding fines in the past six months, smoking cannabis or taking drugs, gambling.

Given that participants were selected through universities and social media, likely favoring individuals with higher digital literacy and more-active profiles, we adopted a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria to avoid potential recruitment bias. Thereby, we generated a group of older adults not representative of the population but matched to the student sample (the young group) with respect to education and a cognitively active lifestyle.

During the screening, the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [

32] was used to evaluate the cognitive functioning of the older adults. The MMSE is a test commonly used to assess dementia in older populations. Three subjects of the older group were excluded from this study because of poor scores in the MMSE (MMSE scores of less than 25).

All participants provided written informed consent prior to the start of the experiment. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the ethics committee of the university in which the research was conducted.

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted in the second half of 2023. Participants were tested in a quiet room of an Italian University. They were tested individually in the morning from 9.00 to 12.00 a.m.

Following informed written consent and completing the screening to assess basic medical histories and to determine eligibility for the study, all participants were invited to complete three questionnaires and to perform a neuropsychological task. The young group and the older group were separately tested; they firstly performed a neuropsychological task, and afterward they compiled three questionnaires in a random order.

2.3. Measurements and Outcomes

Decision-making, risk propensity, sensation-seeking, and self-conscious emotions were assessed by self-reported questionnaires and a neuropsychological task, as follows.

Decision-making under risk: To evaluate decision-making under risk, we used an iterated computerized version of the Prisoner’s Dilemma Game (PDG) [

8]. At the beginning of the game, participants were told a scenario where two prisoners were accused of a crime, and they were informed they were playing against a computer. Participants had to choose between cooperating with or defecting from the computer without knowing the other’s decision. If both players cooperate, they receive a moderate reward. If one defects while the other cooperates, the defector receives a higher payoff while the cooperator receives a low payoff. If both defect, they both receive a lower payoff than if they had cooperated. In each trial of the game, both players simultaneously and independently choose between cooperation and defection. Their decision was made with the memory of all prior interactions. The payoffs for each player at each trial were influenced by their own choice and the choice of the other player.

In accordance with previous studies [

33,

34,

35], the computer cooperated or defected with a probability of 80% cooperative, if the participants had cooperated or defected, respectively, in the previous trial, and with a probability of 20% in which the computer made a random decision. The computer used a tit-for-tat strategy consisting of an initial cooperation after which it always defects immediately after the other player defects. In the literature about the PDG, it is well-known that a tit-for-tat strategy emulates as much as possible the conditions of playing with another human by emphasizing reciprocation, because it encourages cooperation and is unforgiving of defection [

35].

The PDG was constituted by 12 consecutive trials. As stated above, in each trial participants were asked to cooperate or to defect. Participants showed their choices by pressing the right or left control key with their right or left index finger on a keyboard. Then, participants received feedback regarding their own and their interaction partner’s outcome. In the next trial, participants again had to choose whether to cooperate or to defect with the same interaction partner.

Risk propensity: Risk propensity was measured with the Italian Risk Propensity Scale (RPS) [

36]. It is a self-report questionnaire that assesses people’s tendency to undertake risky decisions or behaviors. It consists of 7 items, measured on a 9-point scale (from totally disagree to totally agree: 1–9). The score range is 7–63. The Italian version of the RPS was validated by Marton, Monzani, Vergani, Pizzoli, and Pravettoni [

36], indicating a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.78) and good convergent and discriminant validity.

Sensation-seeking: Sensation-seeking was evaluated with the Italian Sensation-Seeking Scale form-V(SSS-V) [

37]. It is the most widely used self-report standardized questionnaire that assesses this construct. The SSS-V consists of 40 dichotomous items, subdivided into four subscales (10 items for each subscale). The subscales are the following: (a) thrill and adventure-seeking (THR) evaluates the desires to engage in risky sports or activities; (b) experience-seeking (EXP) evaluates the desire to seek an unconventional lifestyle via unplanned activities, unconventional friends, and/or through travel; (c) disinhibition (DIS) assesses the seeking of disinhibited social behavior via alcohol, partying, sex, etc.; (d) boredom susceptibility (BOR) assesses the aversion to repetitive and/or boring tasks, work, behavior, people, etc.

Self-Conscious Emotions: Guilt, shame, and pride were measured with the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA-3S) [

38]. This test is the most widely used instrument to assess self-conscious emotions. TOSCA allows us to assess the degree to which subjects are prone to experience shame, guilt, and pride in 15 different real-life scenarios. It is subdivided into six subscales: shame-proneness (S), guilt-proneness (G), externalization (E), detachment-unconcern (D), alpha-pride (AP), and beta-pride (BP). It consists of 15 scenarios (10 negative and 5 positive) that describe different moral transgressions or adverse events in day-to-day life. Each scenario is presented with three possible responses, and subjects must rate how likely they would be to react in each scenario on a 5-point scale (from “not likely” to “very likely”). Estimates of internal consistency (Cronbach’ alpha) for the TOSCA shame, guilt, and blaming others subscales were 0.73, 0.71, and 0.73, respectively [

39].

2.4. Study Design

This study used a cross-sectional design to compare outcomes between the young and older groups, using the group variable as the independent variable. This study examined four dependent variables (risk propensity, decision-making under risk, sensation-seeking, and self-conscious emotions), which are the outcomes being measured and potentially influenced by the independent variable.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0 for Windows. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables were tabulated and examined. The alpha level was set to 0.05 for all statistical tests. In case of significant effects, the effect size of the test was reported. For ANOVA, a partial eta-squared (pη2) was used, while Cohen’s d effect size measure was applied for t-tests. The Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment for nonsphericity was applied to probability values for repeated measures. To verify the differences between the two groups for each dependent variable, separate repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) or one-way ANOVA were conducted.

The normality of the data was assessed. With reference to risk propensity data, the results of the young group showed that the data were normally distributed, as the skewness (−0.746) and kurtosis (0.594) individually were within ±1. The critical ratio (Z value) of the skewness (−1.462) and kurtosis (0.598) was within ±1.96, also evidently normally distributed. The Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 1.37) was statistically insignificant, that is, data were considered normally distributed, whereas the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p = 0.028) was statistically significant. However, the Shapiro–Wilk test is a more appropriate method for small sample sizes (<50 samples).

In the older group, the results for risk propensity showed that the data were not normally distributed, as the skewness (−1.652) and kurtosis (4.113) individually were not within ±1. Critical ratio (Z value) of the skewness (−3.226) and kurtosis (4.146) was not within ±1.96 suggesting a non-normal distribution of data. Similarly, Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 0.006) was statistically significant, whereas the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p = 0.147) was statistically insignificant; thus, the data were considered normally distributed.

As regards the PDG, the results of the young group showed that the data were normally distributed, as the skewness (−0.379) and kurtosis (−0.027) individually were within ±1. The critical ratio (Z value) of the skewness (−0.743) and kurtosis (0.027) was within ±1.96, also evidently normally distributed. The Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 0.006) and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p = 0.147) were statistically significant; that is, data were not considered normally distributed.

In the older group, the results showed that data were normally distributed, as skewness (−0.132) was within ±1, but kurtosis (−1.323) was not within ±1, suggesting a non-normal distribution. The critical ratio (Z value) of the skewness (−0.257) and kurtosis (−1.333) were within ±1.96, evidently normally distributed. The Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 1.111) was statistically insignificant; that is, data were considered normally distributed. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p = 0.04) was statistically significant but, as stated above, the Shapiro–Wilk test is more appropriate method for small sample sizes.

As shown in

Table 2, with reference to sensation-seeking, data were normally distributed for both groups due to the values of skewness and kurtosis, the Z value, and the

p values of the Shapiro–Wilk test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. However, only in the young group were the Shapiro–Wilk test (

p = 0.02) and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (

p = 0.03) statistically significant for thrill and adventure-seeking, although the skewness and kurtosis and Z value suggested a normal distribution.

As regards self-conscious emotions, data were normally distributed for both groups but the Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 0.01) suggested a normal distribution of data for behavioral pride in the young group. Also, in the older group, data were not considered normally distributed for guilt-proneness due to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p = 0.01) and the Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 0.04), but the skewness (0.83), kurtosis (−0.05), and Z value of the skewness (−1.619) and kurtosis (0.058) suggested a normal distribution of data for guilt-proneness.

Levene’s test of homogeneity of variances indicated that the variances were homogenous, respectively, in risk propensity, F(1,38) = 0.13, p = 0.713; PDG F(1,38) = 2.51, p = 0.121; sensation-seeking, F(1,38) = 0.69, p = 0.410; disinhibition, F(1,38) = 0.60, p = 0.441; boredom susceptibility, F(1,38) = 0.14, p = 0.707; thrill and adventure-seeking, F(1,38) = 0.59, p = 0.810; pride in one’s self, F(1,38) = 2.731, p = 0.107; behavioral pride, F(1,38) = 0.413, p = 0.524; externalization, F(1,38) = 0.10, p = 0.992; detachment/unconcern, F(1,38) = 0.721, p = 0.401; shame-proneness, F(1,38) = 2.49, p = 0.122. Moreover, Levene’s test of homogeneity of variances indicated that the variances were not homogenous in experience-seeking F(1,38) = 4.64, p = 0.03; and in guilt-proneness F(1,38) = 4.68, p = 0.03.

Hence, statistical analysis assumed the data within two groups followed a normal distribution for all parameters being analyzed.

3. Results

With reference to the risk propensity and PDG, the one-way ANOVA indicated that group showed no significant effect, F(1,38) = 1.50, p = 0.54, pη2 = 0.01; F(1,38) = 0.35, p = 0.55, pη2 = 0.01.

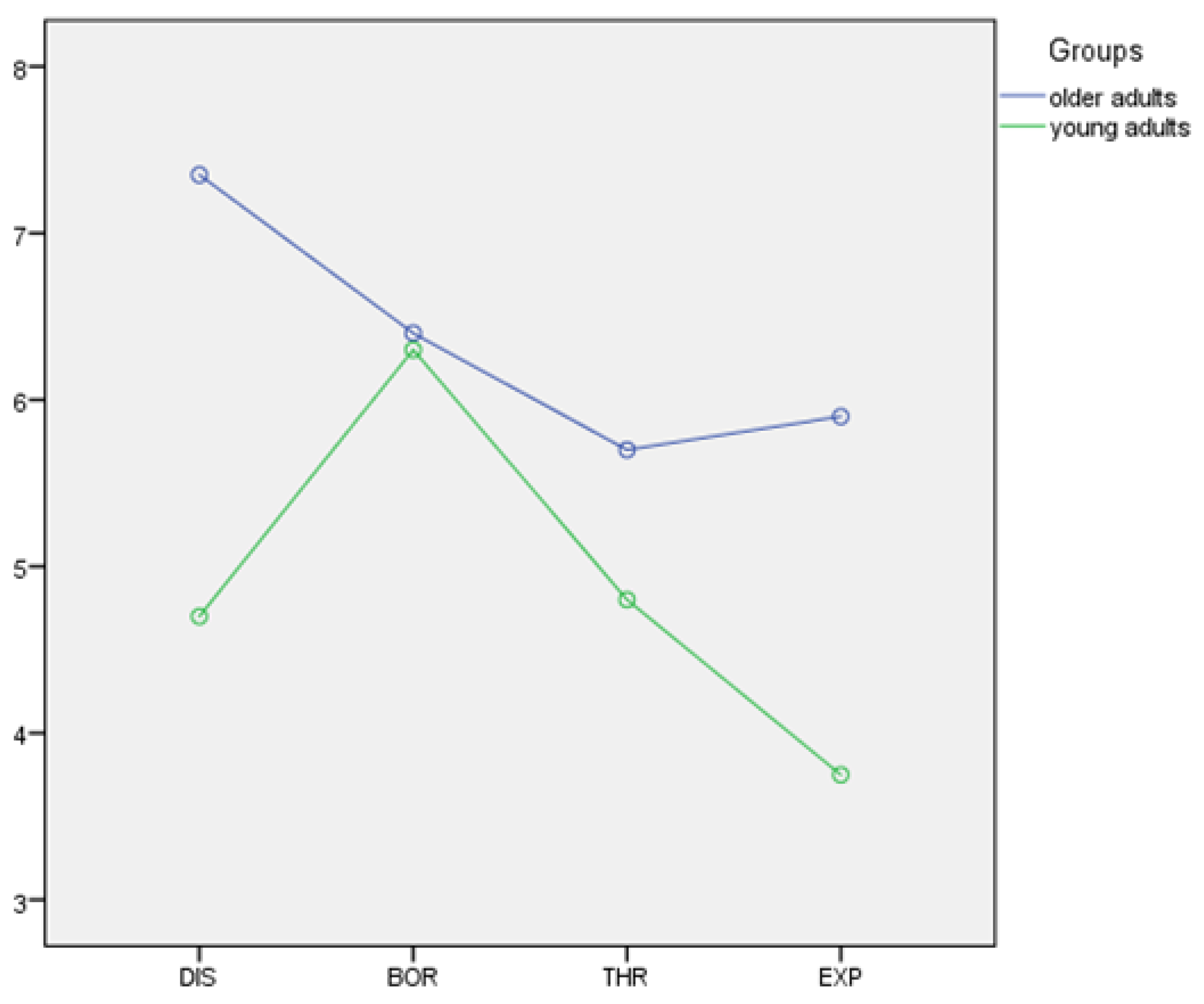

With reference to the factor “seeking new, intense, and risky experiences,” a repeated-measures analysis of variance was carried out with one between-subjects factor and one within-subjects factor: 2 (groups: younger and older adults) X 4 (SSS-V subscales: THR, EXP, DIS, BOR).

Table 3 shows the means (M) and standard deviations (SD) of scores on the SSS-V for the two groups. The group variable showed statistically significant effects, F(1,38) = 11.00,

p < 0.001, pη2= 0.14; this indicated that there were statistically significant differences between the two groups, older adults exhibited a greater tendency toward seeking risky experiences than young adults. Additionally, a significant group X SSS-V interaction effect was found, F(1,38) = 4.47,

p < 0.001. This interaction suggested that the two groups showed different patterns across the various dimensions of the SSS-V (

Figure 1).

Post hoc analyses further corroborated these results, showing that the older group was more inclined to seek risky experiences than the young group in two specific domains of SSS-V: recreational activities and the pursuit of unconventional life experiences, respectively, t(38) = 4.588, p < 0.0001, d = 0.78; t(38) = 3.801, p = 0.001, d = 0.75.

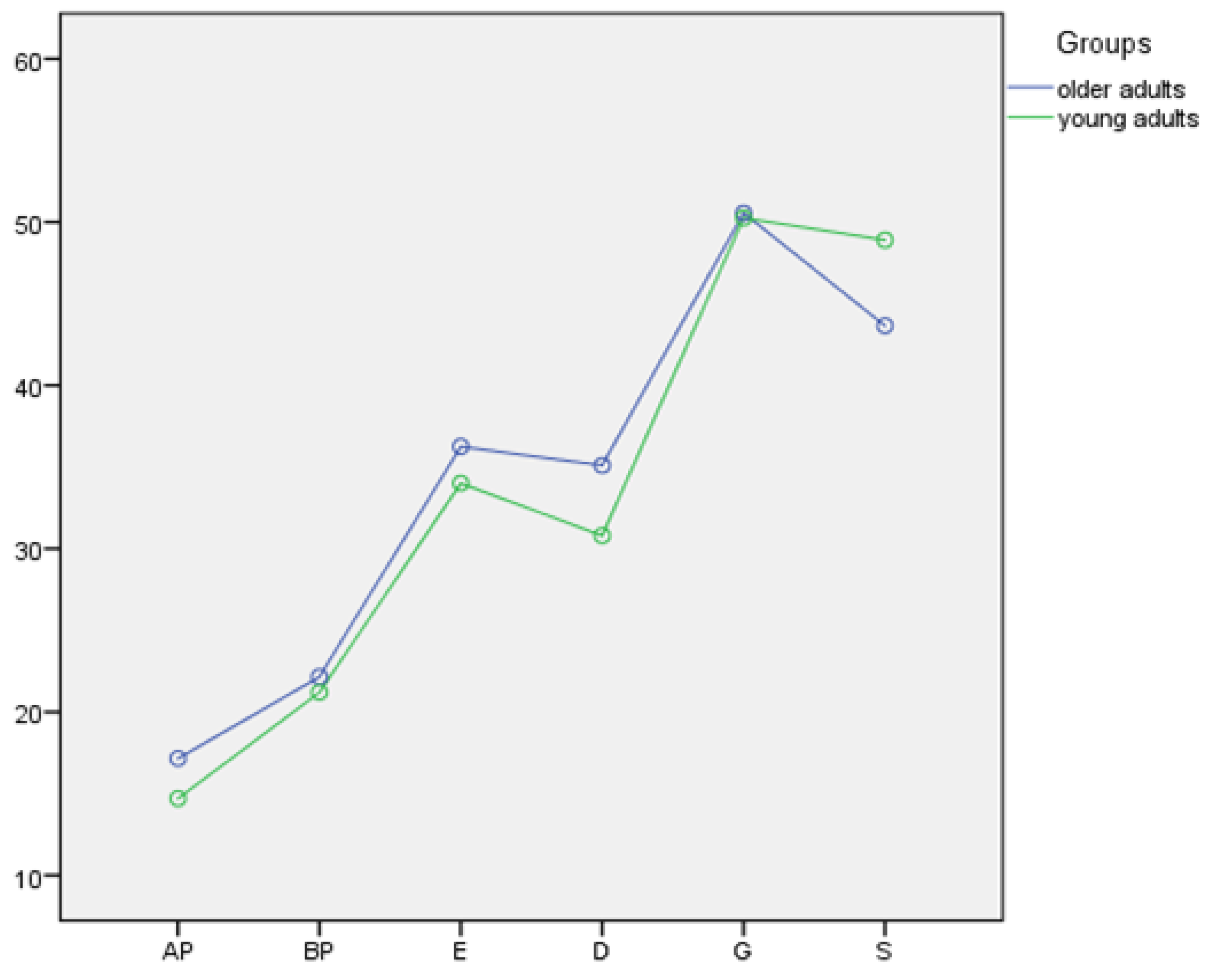

With reference to the factor “self-conscious emotions”, a repeated measures analysis of variance was carried out with one between subjects factor and one within subjects factor: 2 (groups: younger and older adults) X 6 (TOSCA subscales: S, G, E, D, AP, BP).

Table 4 shows the means (M) and standard deviations (SD) of scores in TOSCA for the two groups. The group variable showed significant effects F(1,38) = 4.49,

p < 0.001, pη2 = 0.14; this indicated that the two groups differed in felling the self-conscious emotions. We also found a significant interaction Gruppo X TOSCA, F(1,38) = 3.99,

p < 0.05, indicating that the two groups showed general differences in the six subscales of the TOSCA.

Multiple comparisons for specific emotions (six subscales TOSCA) indicated that the older group were more prone to experience pride in oneself than the young group, t(38) = 2.275,

p < 0.01,

d = 0.78; whereas the young group was more prone to experience shame than the older group t(38) = 2.030,

p < 0.01,

d = 0.76. No difference by group was found for the following emotions: guilt-proneness, externalization, detachment/unconcern, and pride in one’s behavior, respectively, t(38) = 1.127,

p = 0.90; t(38) = 1.804,

p = 0.42; t(38) = 1.645,

p = 0.10; t(38) = 1.866,

p = 0.39.

Figure 2 shows the differences by group for specific emotions.

Given that we found significant differences between the two groups in the tendency towards pride and shame and in seeking recreational activities and unconventional experiences, we verified whether there were correlations across these variables. Correlational analysis with Pearson’s coefficient did not reveal statistically significant correlations between the above-mentioned variables in the two groups. The Cronbach’s alpha of each variable for the groups is presented in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

In this preliminary study, we examined age differences in decision-making under risk, risk propensity, sensation-seeking, and self-conscious emotions between young and older adults. No significant differences were found in the general tendency towards risk-taking and in decision-making behaviors under risk. This result must be interpreted with caution because the sample size of this study is too small, and the null findings in these two key variables could be related to the underpowered sample. However, it confirms the hypothesis that both young and older adults experience the same general risk propensity, and the age differences emerge in specific domains related to decision-making under risk. Hence, the two groups differed in their behavior related to seeking risky, intense, and unconventional experiences; older adults showed a greater propensity for risky behaviors compared to young adults.

Overall, this study suggests that there are age differences in sensation-seeking; older adults are more likely to seek risky, intense, and unconventional activities than young adults. This result suggests that older adults might be risk-averse in repetitive and/or boring tasks, work, behavior, and decisions than younger adults, but risk-seeking in risky, intense, and unconventional activities or tasks. This finding is in line with previous results; research consistently shows that sensation-seeking tends to decline with age, particularly in the domain of disinhibition and thrill and adventure-seeking [

40,

41]. Moreover, the finding that older adults were more risk-averse in repetitive or boring contexts, yet risk-seeking in stimulating ones, is consistent with findings on boredom sensitivity and cognitive engagement in aging. Older adults may actively avoid situations perceived as cognitively or emotionally unstimulating, which may lead them to seek novelty and challenge in selected domains [

42]. This may not be driven by impulsivity but rather a strategic regulation of emotional well-being and interest, consistent with Socioemotional Selectivity Theory [

43]. However, this result should be interpreted with caution due to the exploratory nature of this study and since we used only a self-report scale measuring sensation-seeking. Further research, with other experimental tasks or self-report questionnaires, is necessary to confirm these results.

However, as stated in the Introduction of this paper, it is important to evidence that sensation-seeking and risk-taking are two different constructs, though they are correlated [

11,

12]: risk-takers are more inclined to engage in risky decisions, while sensation-seekers are more willing to take chances for higher rewards [

13]. Moreover, sensation-seeking is motivational and driven by the desire for arousal and novelty, whereas risk-taking refers to behaviors that involve potential losses and uncertain outcomes. But not all high-sensation activities involve high risk (e.g., trying a new cuisine), and not all risky behaviors are sensation-driven (e.g., financial decisions made under stress). In addition, we propose that risk-taking is domain-specific, which means that an older adult may avoid financial or health-related risks but still pursue high-intensity experiences like adventure tourism. This aligns with dual-process models of decision-making [

44] where experience and affect play increasing roles in risk evaluation with age.

Hence, our finding that older adults may be selectively risk-seeking in intense and unconventional domains, while being risk-averse in mundane or repetitive contexts, suggests a need to rethink age-related stereotypes about risky behavior, and it also highlights the importance of distinguishing sensation-seeking from risk-taking in future research.

In terms of decision-making across different emotional scenarios, we found that older adults showed a greater inclination toward pride, whereas younger adults exhibited a stronger tendency towards shame. This result can be explained through different perspectives. From the point of view of emotion-regulation abilities, younger and older adults differ in emotional reactivity and regulation, which may lead to age-related differences in how pride and shame shape risky choices. Older adults typically show greater emotional regulation [

45,

46,

47], so pride can serve as a motivational emotion, leading them to avoid risks that might compromise the positive self-image they have cultivated over a lifetime. Shame, by contrast, is a negative emotion linked to perceived failure or moral transgression. In young adults, it tends to produce avoidance behaviors and may lead to more risk-averse decision-making, particularly in contexts where social judgment is salient. From the point of view of Socioemotional Selectivity Theory, as people age, they prioritize emotionally meaningful goals and experiences. Pride, a positive self-conscious emotion, reinforces one’s identity, legacy, and accomplishments. Decisions that align with maintaining a sense of dignity, wisdom, or moral integrity are often favored, even if they involve avoiding potentially high reward but risky options. From the point of view of Cognitive Appraisal Theory, older adults tend to evaluate situations through a lens of self-consistency and self-validation. When pride is activated, they may prefer safe, socially acceptable decisions that uphold their perceived competence and experience.

Hence, this result suggests that affectivity plays a significant role in decision-making behavior, with pride influencing older adults and shame influencing younger adults. Future research could examine the age-dependent effects of pride and shame on risky decision-making.

Contrary to common assumptions that younger adults are more inclined towards risky activities, the data suggests that older adults may be more likely to engage in activities that are intense, unconventional, and carry higher levels of risk. As explained above, this result can be in line with our finding that older adults are more inclined towards pride while younger adults lean towards shame, and it suggests a shift in risk preferences as individuals age, potentially influenced by a variety of psychological, social, and experiential factors. With reference to the underlying mechanisms or contributing factors, a more comprehensive analysis could consider several potential explanations for this shift. For instance, cognitive aging may lead to a reduced information processing capacity, prompting older individuals to make safer choices. Additionally, changes in life circumstances, such as reduced income stability post-retirement, shorter time horizons, or increased responsibilities, may also contribute to heightened risk-aversion. Psychological factors, including a greater focus on loss avoidance or changes in emotional regulation, may further influence decision-making. As regards emotional factors, we found that younger adults were more susceptible to the influence of shame, whereas older adults were more likely to be influenced by pride in their decision-making, particularly in the context of risk-aversion and self-image regulation. Therefore, it is a reasonable conclusion that pride and shame warrant more in-depth study within the realm of interactions between self-conscious emotions and decision-making under risk. Future research could explore these hypotheses using longitudinal data or neuroeconomic approaches to better understand the complex interplay between aging and risk preference.

An alternative explanation about this finding could be that participants were recruited through flyers in universities, social venues, and social-media pages, and it is known that young people are abundant in universities. Therefore, there could have been a selection bias in that we may have recruited older people who are more adventurous. However, with a small sample size, caution must be applied; future studies should collect a larger sample with different recruitment methods to mitigate potential selection biases.

The present study has different limitations. Firstly, as stated above, the sample size was small, which can affect the power of the study and the reliability of the findings. To improve the robustness of the study’s conclusions and to enhance the statistical power and reliability of the results, it is important to increase the sample size in future studies. In addition, there was a gender imbalance in the young group (95% women), which could introduce a potential bias limiting the generalizability of the findings; consequently, future research should replicate this study using a large sample of participants matched for age and gender.

Secondly, as stated above, there was a potential selection bias in the recruitment of participants, given that they were recruited through flyers in universities, social venues, and social-media pages. In addition, a single-center design in one country, likely in an urban setting, may not reflect the experiences of individuals in rural areas. Urban settings tend to be densely populated with high concentrations of services and infrastructure, while rural areas often have sparser populations, limited resources, and a more agrarian way of life. These factors could influence decision-making under risk, so future research should use different methods of participants recruitment to mitigate and to avoid the risk of potential selection bias and to ensure the generalizability of the results to rural contexts as well.

Thirdly, this study did not examine the potential influence of various sociodemographic factors that may affect decision-making, such as marital status (e.g., single, married, divorced) and income or financial status. Previous research suggests that individuals who are single or possess more financial resources may demonstrate a greater willingness to engage in risk-taking behaviors, whereas those with more constrained financial means may exhibit more risk-averse tendencies [

48]. These variables could interact with age and sensation-seeking tendencies in complex ways, potentially moderating or mediating the observed patterns of risk behavior. Future research would benefit from incorporating such variables to better contextualize risk preferences across different life stages and socioeconomic backgrounds. Investigating these factors could yield a better understanding of how individual differences shape risk-related decision-making and contribute meaningful insights to the broader literature on lifespan development and behavioral economics.

The current study offers important implications for health interventions, workplace design, and social services aimed at aging populations. First, it highlights the importance of tailoring risk communication to align with both the domain of risk (i.e., economic, health, unconventional activities) and the motivational profiles of older adults, recognizing that risk-aversion may not be universal but domain-specific. Second, in occupational settings, the findings suggest the benefit of reducing monotonous or repetitive tasks for older workers and instead incorporating novelty, variety, and cognitive challenge to maintain engagement and satisfaction. Lastly, in the context of social and recreational services, there is value in promoting high-arousal experiences for older people, such as travel, cultural activities, and cognitively stimulating pursuits, that fulfill sensation-seeking tendencies in a purposeful and age-appropriate manner.