Falls of Older Adults: Which Is Worse, Falling or Fear of Falling?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Procedure

2.2. The Sample

2.3. Measurements

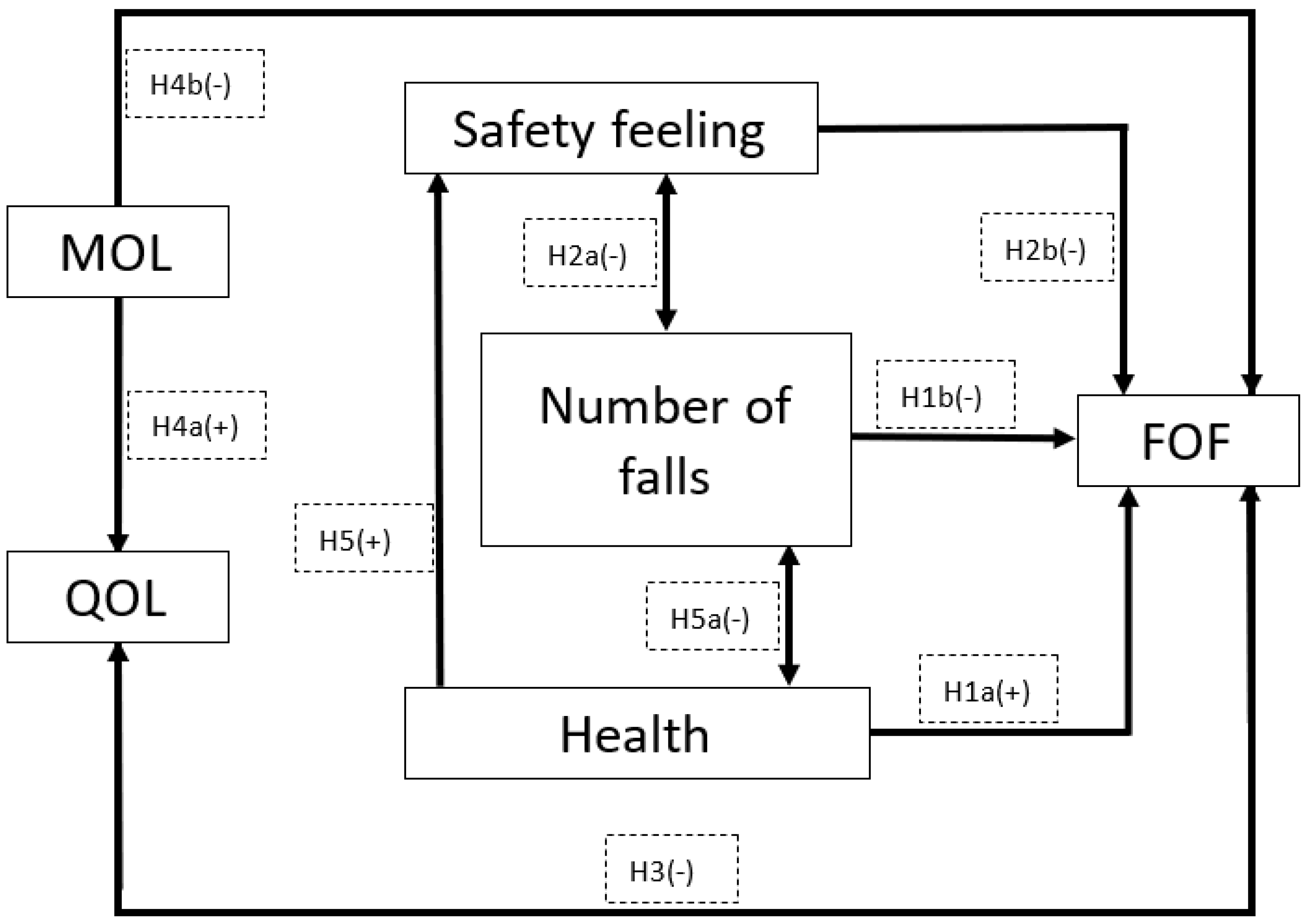

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Reliability of the Questionnaires

3.2. Pearson Correlation

3.3. Comparing Those Who Have and Have Not Fallen

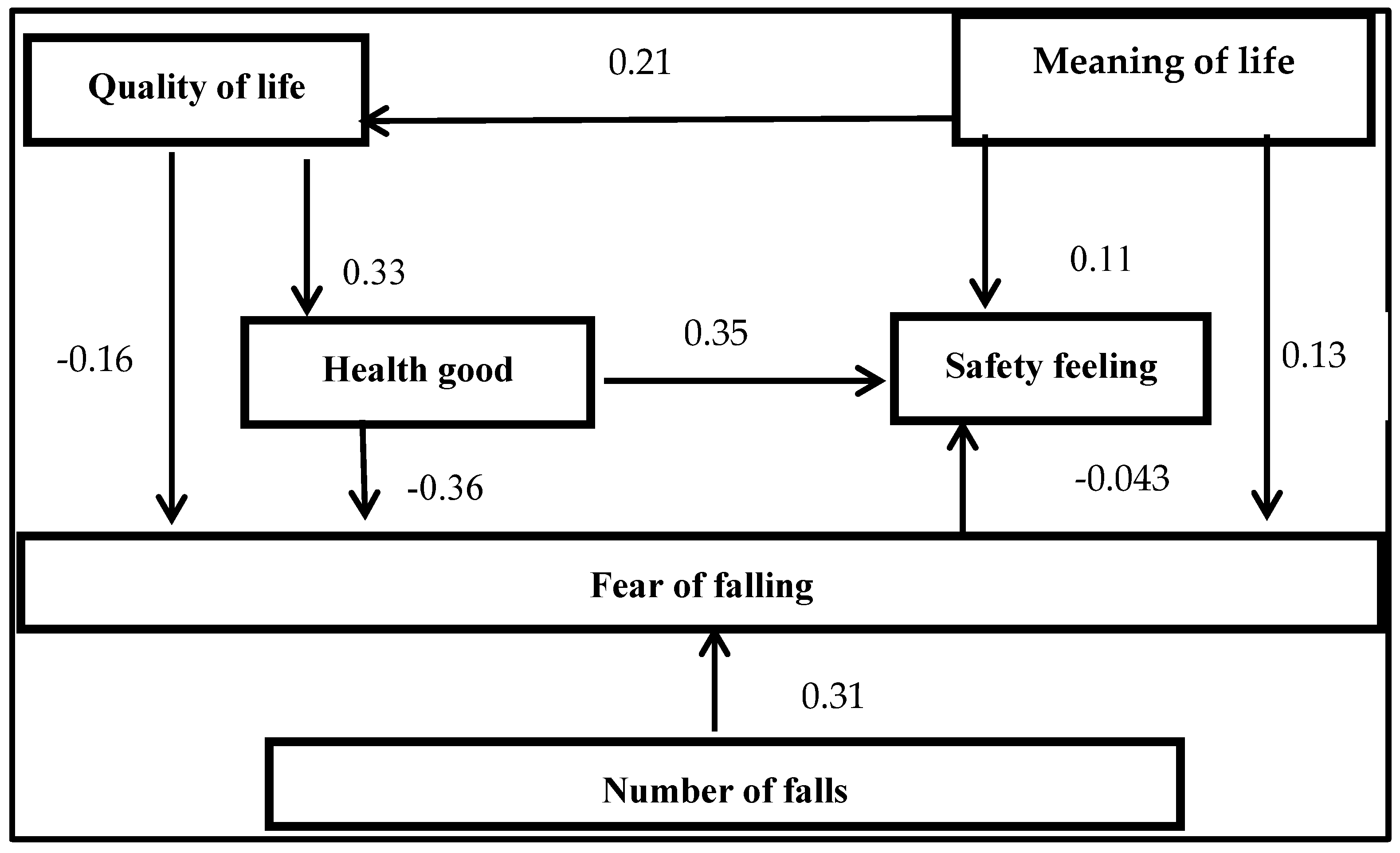

3.4. The Relationships Between Fear of Falling and the Other Variables

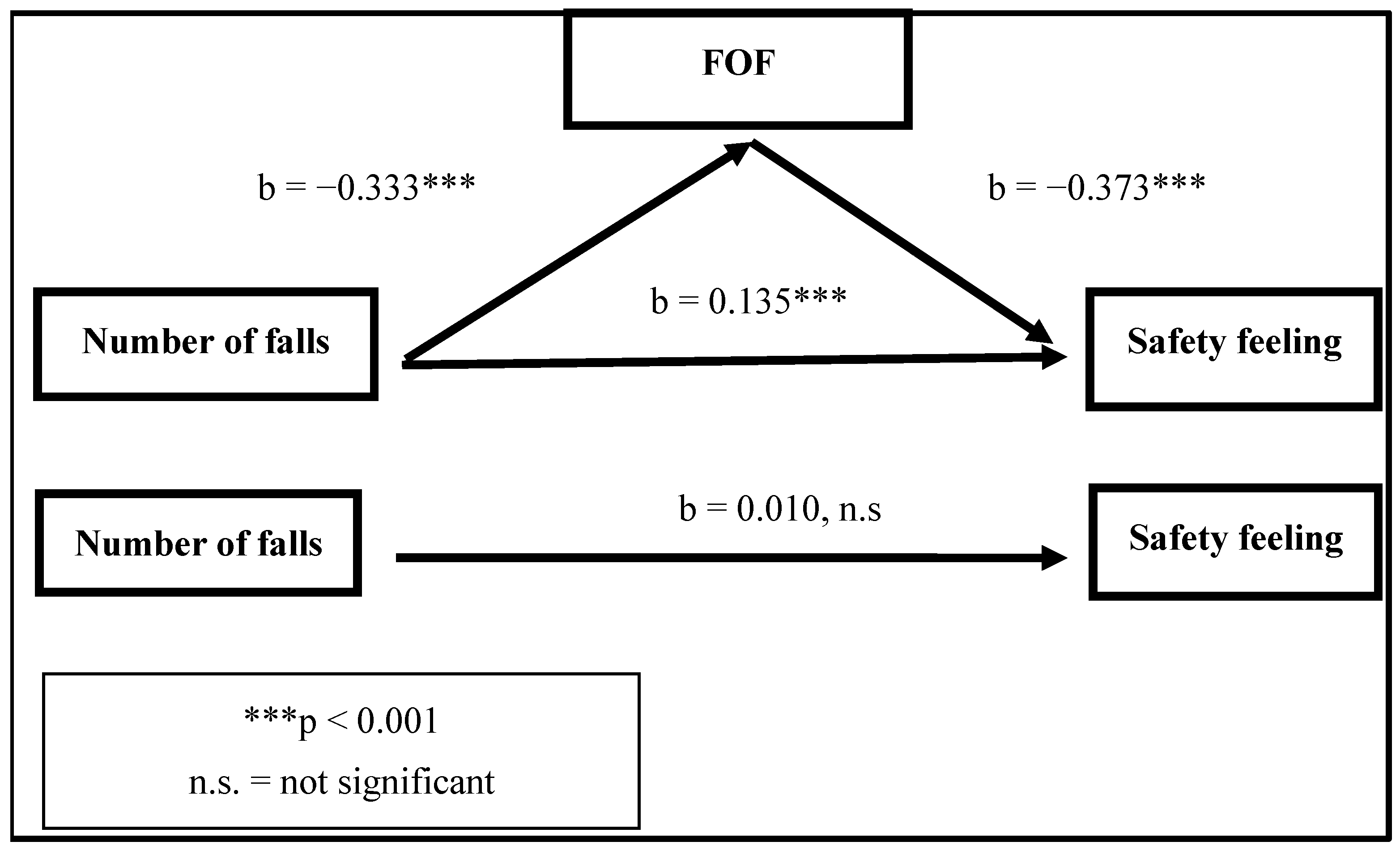

3.5. Fear of Falling as a Mediator Between the Number of Falls and Safety Feeling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Israel Ministry of Health. Israel National Elderly Falls Survey 2019; Israel Ministry of Health, National Center for Disease Control: Jerusalem, Israel, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/israel-national-elderly-falls-survey-2019/he/files_publications_units_ICDC_israel-national-elderly-falls-survey-2019.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- World Health Organization. Falls; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Xie, Q.; Pei, J.; Gou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Dou, X. Risk Factors for Fear of Falling in Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Y.K.; Bergen, G.; Florence, C.S. Estimating the Economic Burden Related to Older Adult Falls by State. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2019, 25, E17–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.A.; Daigle, S.G.; Weiss, R.; Wang, Y.; Arora, T.; Curtis, J.R. Economic Burden of Osteoporosis-Related Fractures in the US Medicare Population. Ann. Pharmacother. 2021, 55, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Isaacs, B. The Post-Fall Syndrome. Gerontology 1982, 28, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Powell, L. 4 Fear of Falling and Low Self-Efficacy: A Cause of Dependence in Elderly Persons. J. Gerontol. 1993, 48, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellmers, T.J.; Wilson, M.R.; Norris, M.; Young, W.R. Protective or Harmful? A Qualitative Exploration of Older People’s Perceptions of Worries about Falling. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Wang, D.; Ren, W.; Liu, X.; Wen, R.; Luo, Y. The Global Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Fear of Falling among Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.; Sales, W.; Tavares, D.; Pereira, D.; Nóbrega, P.; Holanda, C.; Maciel, A. Relationship between Pain, Fear of Falling and Physical Performance in Older People Residents in Long-Stay Institutions: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, E.P.R.; Ohara, D.G.; Patrizzi, L.J.; De Walsh, I.A.P.; Silva, C.D.F.R.; Da Silva Neto, J.R.; Oliveira, N.G.N.; Matos, A.P.; Iosimuta, N.C.R.; Pinto, A.C.P.N.; et al. Investigating Factors Associated with Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults through Structural Equation Modeling Analysis: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, D.-Y.; Shin, K.-R.; Kang, Y.-H.; Kang, J.-S.; Kim, K.-H. A Study on the Falls, Fear of Falling, Depression, and Perceived Health Status among the Older Adults. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2008, 20, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bhala, R.P.; O’Donnell, J.; Thoppil, E. Ptophobia: Phobic Fear of Falling and Its Clinical Management. Phys. Ther. 1982, 62, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tideiksaar, R. Falls in Older People: Prevention and Management, 4th ed.; Health Professions Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2010; ISBN 1-932529-44-6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Hou, T.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Szanton, S.L.; Clemson, L.; Davidson, P.M. Fear of Falling Is as Important as Multiple Previous Falls in Terms of Limiting Daily Activities: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M.; Schnorr, T.; Morat, M.; Morat, T.; Donath, L. Effects of Mind–Body Interventions Involving Meditative Movements on Quality of Life, Depressive Symptoms, Fear of Falling and Sleep Quality in Older Adults: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akosile, C.O.; Igwemmadu, C.K.; Okoye, E.C.; Odole, A.C.; Mgbeojedo, U.G.; Fabunmi, A.A.; Onwuakagba, I.U. Physical Activity Level, Fear of Falling and Quality of Life: A Comparison between Community-Dwelling and Assisted-Living Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.M.; Munoz, B.; West, S.K.; Rubin, G.S.; Fried, L.P. Falls and Fear of Falling: Which Comes First? A Longitudinal Prediction Model Suggests Strategies for Primary and Secondary Prevention. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.L.; Dubin, J.A.; Gill, T.M. The Development of Fear of Falling among Community-Living Older Women: Predisposing Factors and Subsequent Fall Events. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, M943–M947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.R.; Mark Williams, A. How Fear of Falling Can Increase Fall-Risk in Older Adults: Applying Psychological Theory to Practical Observations. Gait Posture 2015, 41, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.C.; Hart, D.; Spector, T.; Doyle, D.V.; Harari, D. Fear of Falling Limiting Activity in Young-Old Women is Associated with Reduced Functional Mobility Rather than Psychological Factors. Age Ageing 2005, 34, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Fisher, K.J.; Harmer, P.; McAuley, E.; Wilson, N.L. Fear of Falling in Elderly Persons: Association with Falls, Functional Ability, and Quality of Life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003, 58, P283–P290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, K.M.; Kokko, K.; Kekäläinen, T.; Alén, M.; Hänninen, T.; Pynnönen, K.; Laukkanen, P.; Tirkkonen, A.; Törmäkangas, T.; Sipilä, S. Associations of Neuroticism with Falls in Older Adults: Do Psychological Factors Mediate the Association? Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, B.; Musselman, K.; Culham, E. Physical Function and Health Status among Seniors with and without a Fear of Falling. Gerontology 2004, 50, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemson, L.; Cumming, R.G.; Heard, R. The Development of an Assessment to Evaluate Behavioral Factors Associated with Falling. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2003, 57, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orihuela-Espejo, A.; Álvarez-Salvago, F.; Martínez-Amat, A.; Boquete-Pumar, C.; De Diego-Moreno, M.; García-Sillero, M.; Aibar-Almazán, A.; Jiménez-García, J.D. Associations between Muscle Strength, Physical Performance and Cognitive Impairment with Fear of Falling among Older Adults Aged ≥ 60 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkeld, G.; Cameron, I.D.; Cumming, R.G.; Easter, S.; Seymour, J.; Kurrle, S.E.; Quine, S. Quality of Life Related to Fear of Falling and Hip Fracture in Older Women: A Time Trade off Study. BMJ 2000, 320, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soh, S.L.-H.; Tan, C.-W.; Thomas, J.I.; Tan, G.; Xu, T.; Ng, Y.L.; Lane, J. Falls Efficacy: Extending the Understanding of Self-Efficacy in Older Adults towards Managing Falls. J. Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2021, 6, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, K.A.; Zhou, W.; Rojer, A.G.M.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Maier, A.B. Associations of Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour with Fall-Related Outcomes in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 65, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoene, D.; Heller, C.; Aung, Y.N.; Sieber, C.C.; Kemmler, W.; Freiberger, E. A Systematic Review on the Influence of Fear of Falling on Quality of Life in Older People: Is There a Role for Falls? Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halama, P.; Dědová, M. Meaning in Life and Hope as Predictors of Positive Mental Health: Do They Explain Residual Variance Not Predicted by Personality Traits? Stud. Psychol. 2007, 49, 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, A.; Banister, D.; Sutton, S.; Evans, O.; Windsor, J. A Multidimensional Model of the Quality of Life in Older Age. Aging Ment. Health 2002, 6, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, K.M.; Van Loon, M.S.; Van Nes, F.A.; Bosmans, J.E.; De Vet, H.C.W.; Ket, J.C.F.; Widdershoven, G.A.M.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G. What Does Quality of Life Mean to Older Adults? A Thematic Synthesis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186463 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Rietdyk, S.; Ambike, S.; Amireault, S.; Haddad, J.M.; Lin, G.; Newton, D.; Richards, E.A. Co-Occurrences of Fall-Related Factors in Adults Aged 60 to 85 Years in the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuben, D.B.; Wieland, D.L.; Rubenstein, L.Z. Functional Status Assessment of Older Persons: Concepts and Implications. Facts Res. Gerontol. 1993, 7, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde, C.; Ankri, J.; Cambois, E. Environmental Barriers Matter from the Early Stages of Functional Decline among Older Adults in France. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lethborg, C.; Aranda, S.; Cox, S.; Kissane, D. To What Extent Does Meaning Mediate Adaptation to Cancer? The Relationship between Physical Suffering, Meaning in Life, and Connection to Others in Adjustment to Cancer. Palliat. Support. Care 2007, 5, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, C.; Ostafin, B.; Juhl, J.; Sedikides, C.; Cathey, C.; Liao, J. Adjusting to Death: The Effects of Mortality Salience and Self-Esteem on Psychological Well-Being, Growth Motivation, and Maladaptive Behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 99, 897–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibabaei, M.; Kajbaf, M.B.; Esmaeili, M.; Harirchian, M.H.; Montazeri, A. Impact of an Existential-Spiritual Intervention Compared with a Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Quality of Life and Meaning in Life among Women with Multiple Sclerosis. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2020, 15, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitler, S. Meanings of Meaningfulness of Life. In Logotherapy and Existential Analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute Vienna; Batthyány, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 95–106. ISBN 978-3-319-29423-0. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, L.; Ribeiro, O.; Paúl, C. Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being in Old Age through Positive Psychology Studies: A Scoping Review. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.E.; Myers, A.M. The Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1995, 50A, M28–M34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Linley, P.A.; Harwood, J.; Lewis, C.A.; McCollam, P. Rapid Assessment of Well-being: The Short Depression-Happiness Scale (SDHS). Psychol. Psychother. 2004, 77, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Gandek, B. Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahat Öztürk, G.; KiliÇ, C.; Bozkurt, M.E.; Karan, M.A. Prevalence and Associates of Fear of Falling among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyper, G.M.A.; Fletcher, E.; Grant, I.; McCartney, G.; Fischbacher, C.; Harding, O.; Jones, H.; De Haro Moro, M.T.; Speybroeck, N.; Devleesschauwer, B.; et al. Measuring Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) Due to COVID-19 in Scotland, 2020. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, S.; Long, L.; Gandhi, V.; Bashir, M. Empowering Older Adults in Underserved Communities—An Innovative Approach to Increase Public Health Capacity for Fall Prevention. J. Ageing Longev. 2023, 3, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Lim, Y.V.; Wee, L.S.X.; Tan, Y.J.S.; Xue, A.L. The Usability of Hip Protectors: A Mixed-Method Study from the Perspectives of Singapore Nursing Home Care Staff. J. Ageing Longev. 2024, 4, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvakis, I.; Adamakidou, T.; Kleisiaris, C. Physical-Activity Interventions to Reduce Fear of Falling in Frail and Pre-Frail Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024, 15, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Had Fallen (203) | Had not Fallen (200) | Total 403 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | % | Average | % | % | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male Female | 43.3 56.7 | 57.0 43.0 | 50.1 49.9 | ||

| Age (years) | 67.4 ±8.14 | 68.3 ±7.71 | 67.9 ±8.00 | ||

| Education | |||||

| Below academic Academic | 46.8 53.2 | 47.5 52.5 | 47.3 52.9 | ||

| Income | |||||

| Below average Similarly to average Higher than average | 23.6 51.2 25.1 | 18.5 58.5 23.0 | 22.1 55.3 24.0 | ||

| Scale | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Safety feeling | 22 | 0.96 |

| Quality of life | 6 | 0.91 |

| Health status | 3 | 0.80 |

| Meaning of life | 40 | 0.94 |

| Number of falls | 8 | 0.49 |

| Fear of falling | 6 | 0.80 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of falls (1) | 1 | |||||

| Fear of falling (2) | 0.355 ** | 1 | ||||

| Meaning of life (3) | 0.048 | 0.078 | 1 | |||

| Quality of life (4) | 0.070 | −0.254 ** | 0.199 ** | 1 | ||

| Safety feeling (5) | −0.217 ** | −0.580 ** | 0.073 | 0.236 ** | 1 | |

| Health status (6) | −0.174 ** | −0.428 ** | 0.179 ** | 0.404 ** | 0.531 ** | 1 |

| BADL | 0.191 ** | −0.545 ** | ||||

| IADL | 0.225 ** | −0.568 |

| Those Who Fell | Those Who Did Not Fall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Sd) | Mean (Sd) | T | p | |

| FOF | 2.790 (0.898) | 2.130 (0.764) | 7.953 | <0.001 |

| Safety feeling | 4.385 (0.656) | 4.612 (0.476) | −3.960 | <0.001 |

| Good health | 3.812 (0.877) | 4.122 (0.711) | −3.816 | <0.001 |

| Relationships | Standardized Effect | Regression Weights (Direct) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Direct | Indirect | Estimate | C.R. | p | |||

| Number of falls | vs. | safety | −0.140 | 0.000 | −0.140 | |||

| MOL | vs. | safety | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.038 | |||

| Health status | vs. | safety | 0.517 | 0.350 | 0.166 | 0.193 | 8.516 | <0.001 |

| FOF | vs. | safety | −0.455 | −0.428 | −0.027 | −0.281 | −10.39 | <0.001 |

| QOL | vs. | safety | 0.172 | 0.000 | 0.172 | |||

| FOF | vs. | QOL | −0.162 | −0.158 | −0.003 | −0.113 | −3.016 | <0.01 |

| MOL | vs. | QOL | 0.201 | 0.211 | −0.010 | 0.237 | 4.456 | <0.001 |

| Number of falls | vs. | FOF | 0.314 | 308 | 0.006 | 0.271 | 7.191 | <0.001 |

| MOL | vs. | FOF | 0.062 | 0.128 | −0.066 | 0.201 | 2.927 | <0.01 |

| Health status | vs. | FOF | −0.373 | −0.366 | −0.077 | −0.307 | −8.011 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Even-Zohar, A.; Kreitler, S.; Gendel Guterman, H. Falls of Older Adults: Which Is Worse, Falling or Fear of Falling? J. Ageing Longev. 2025, 5, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5020020

Even-Zohar A, Kreitler S, Gendel Guterman H. Falls of Older Adults: Which Is Worse, Falling or Fear of Falling? Journal of Ageing and Longevity. 2025; 5(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleEven-Zohar, Ahuva, Shulamith Kreitler, and Hanna Gendel Guterman. 2025. "Falls of Older Adults: Which Is Worse, Falling or Fear of Falling?" Journal of Ageing and Longevity 5, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5020020

APA StyleEven-Zohar, A., Kreitler, S., & Gendel Guterman, H. (2025). Falls of Older Adults: Which Is Worse, Falling or Fear of Falling? Journal of Ageing and Longevity, 5(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5020020