Abstract

Background: Cognitive decline does not always occur; therefore, it is important to recognise the predictors in people over 60. The COVID-19 pandemic led to isolation to limit the spread of the virus, with older people being the most affected. Objectives: To analyse the cognitive variables of older adults in confinement during COVID-19 using tele-neuropsychology for cognitive assessment, comparing online with in-person screening. Methods: In total, 148 subjects took part in the study. Participants were assigned to the in-person or online intervention based on their preferences. A person close to the patient also participated in the study as an informant. Results: The results support the suitability of the protocol used in both modalities (face-to-face/online). Conclusions: Both assessments (face-to-face and online) are equally effective. The findings are consistent with the importance of cognitive measures and the key informant corroboration in identifying indicators of cognitive decline and implementing early intervention strategies.

1. Introduction

Aging is associated with a decline in some cognitive functions and a slowing of executive functions, although both dimensions are within the parameters of normal evolutionary development. However, increased life expectancy is associated with increased vulnerability to cognitive impairment and there is a role for other biographical and contextual cues [1,2]. One of the key elements, according to the World Report on Dementia, is the high rate of older adults who are unaware of their level of impairment and the consequent risk of dementia [3].

The purpose of this study is to examine the variables that predict the vulnerability to MCI and to compare the modes of administration between the traditional face-to-face assessment and the virtual assessment. We emphasize the key to screening for MCI as the focus of research, not the diagnosis of MCI, which should be carried out with neuropsychological assessment procedures and biomarkers.

To achieve early detection in large populations, we need screening tests with good sensitivity, specificity, and efficacy, as well as positive and negative predictive values. In this sense, recent research has increasingly focused on the validation and reliability of digital cognitive assessments, particularly in response to the growing demand for remote healthcare solutions. Computerized and online versions of traditional neuropsychological tests, such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), have shown promising levels of equivalence compared to their in-person counterparts [4]. These tools have proven especially valuable for evaluating cognitive functioning in older adults, offering accessible and scalable alternatives without significantly compromising diagnostic accuracy [5]. Therefore, exploring the potential differences between online and offline performance in cognitive screening instruments is both timely and relevant.

According to the updated criteria proposed by the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association [6] and the International Working Group [7] the distinction between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild dementia is primarily based on the individual’s level of functional autonomy, especially in terms of instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). MCI involves cognitive decline that does not significantly interfere with complex daily tasks such as managing finances, preparing meals, using public transportation, or handling medication. In contrast, mild dementia entails functional loss in these domains, requiring supervision or assistance.

In this context, the inclusion of informant-based tools such as the IDDD—which directly assesses both basic and instrumental functioning—and the IQCODE—which captures perceived cognitive decline over time—offers valuable complementary information. While the IQCODE is not a functional scale in itself, it reflects functional consequences of cognitive change from the informant’s point of view, in line with the perspective outlined by Lezak et al. [8]. Together, these instruments enhance the ecological validity of the screening protocol and support a multidimensional approach to early detection.

The aging of the population has led to an increase in MCI in the elderly, which has augmented the prevalence of dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s Disease [3]. In the continuum of cognitive impairment, MCI is the clinical entity that precedes AD [9]. Therefore, the detection of MCI is important for a clinical and early approach to the diagnosis of AD.

Research in this area emphasizes that MCI is a transitional stage between normality and dementia, involving problems with higher mental processes but with little functional impact [10]. Concerning to neuropsychological symptoms, criteria based on amnestic dysfunction were first used to objectify the diagnosis of MCI [11], and the construct was subsequently expanded [12] to include MCI-amnestic, MCI-amnestic domain, MCI-amnestic multidomain, and MCI-non-amnestic, domain, or multidomain [9]. Subsequently, the NIA-AAA [6] and the National Institute of Alzheimer’s Work Group [7] established new dementia criteria using clinical, neuropsychological, and biomarker criteria that advance the diagnosis of prodromal AD.

For older adults, healthy aging is directly related to their autonomy, understood as the functional capacity required to perform basic, instrumental, and advanced activities of daily living. A study [13] suggests that deterioration in instrumental activities of daily living has a significant correlation with MCI. Therefore, a basic criterion for establishing the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment is to assess the level of autonomy in activities of daily living, as functionality may be a prognostic factor in determining the degree of progression to dementia in the short or medium term [14].

In addition, the literature consistently points to the role that emotional changes play in cognitive decline and overall well-being [15,16]. Isolation and lack of social contacts would act as inhibitors of the stimulation that interpersonal relationships provide for cognitive maintenance.

Thus, the basic differentiating key between the two is the impact or absence of impairment while performing instrumental daily living activities (IDLAs). This third key, autonomy in performing IDLAs (instrumental, basic, and advanced), is not independent of the previous ones, therefore its impairment could be an indicator of a greater risk of developing a major neurocognitive disorder. This must be considered a risk in cognitive assessment, especially in screening tests [17], because some protective factors, such as cognitive reserve, may mask the decline and its progression [18]. This is even more important considering the impact of the pandemic on the cognitive and emotional health of older people, as reflected in recent longitudinal studies showing accelerated decline due to the pandemic [19].

The use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for screening and intervention (cognitive stimulation) has increased in recent years, being beneficial for mild cognitive impairment detection when used in the early stages of mild cognitive impairment [16]. Hence, the importance of implementing alternative tele-neuropsychological care for the elderly, especially considering the situation experienced after the COVID-19 pandemic. The proposal presented in this study follows this line, offering alternative care for the elderly at home, avoiding the risk of personal contact in circumstances like the pandemic.

In addition, the variables were explored in two assessment modalities (face-to-face and online), combining objective information on the elderly’s performance with that provided by key informants (family members or people in the environment), who can corroborate certain changes or dysfunctions and the evolution throughout recent years, is relevant.

This research was developed during the pandemic by COVID-19, in the context of the need to provide cognitive stimulation to the elderly and to prevent cognitive impairment during confinement, hence the creation of the Cognitive Impairment Unit.

At that time, in trying to address the cognitive needs of such a vulnerable population, it was necessary to assess cognitive status to develop the strategies to be implemented. However, in some cases, it was not possible to carry out the face-to-face assessment due to the health emergency at the time.

It was then that the objectives of this study were defined, which were to discriminate the most relevant variables to explore the probable risk of cognitive impairment in elderly people who are users of the MCI Unit using online/in-person assessment and to develop the strategies for their benefit.

This population is made up of elderly people from the city of Salamanca, with a demand for personalised care. Anyone from this environment can come to the unit, which reduces the bias of overrepresentation of some groups over others. Then, once they arrive, it is the user who decides which modality he/she wants to attend.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants were recruited from March 2021 to July 2022; 148 subjects were cognitively assessed (plus the key informant being a caregiver or a close relative to the participant, a total of 296 subjects participated in the study). Subjects included in the sample were recruited in two ways. Firstly, through the Municipal Centers for the Elderly of the City Council of Salamanca. Secondly, through the users who came directly to request the services from the MCI Unit (MU) at the Psychology Faculty in the Pontifical University of Salamanca (UPSA).

Of the 148 subjects, 23.6% = 39 were male and 76.4% = 109 were female. The mean age was 72.91 years (SD 6.46). Finally, the 148 subjects were assigned to an intervention modality (face-to-face or online) previously requested by the participant. For each one of the modalities, data were selected from 79 subjects who met the inclusion criteria. In addition, 148 key informants participated, of whom 47.3% = 70 were men and 52.7% = 78 were women. In terms of relationship to the participants, 77.7% of the key informants were first-degree relatives, while 22.3% were second-degree relatives.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows:

- -

- Participants must be residents of the city of Salamanca, Spain.

- -

- Be at least 60 years old at the time of selection.

- -

- Not be institutionalized in a nursing home.

- -

- Not have a previous diagnosis of MCI.

- -

- Able to give informed consent.

- -

- Willingness to attend the scheduled appointments and complete the required questionnaires.

Regarding the inclusion criteria, it should be noted that cognitively healthy older adults (without previous diagnosis of cognitive impairment) were included since this is a population-based study on demand. This means that the MU should be available for all situations where an assessment of the Subjective Memory Complaints (SMCs) is requested since it is a service financed by a public institution to cover a need that is not offered in primary healthcare systems. The basic task of the MU is to become a sentinel epidemiological surveillance unit to refer to specialized services the cases that, according to the above assessment, are at high risk of possible MCI.

2.2. Instruments

A questionnaire was used to obtain the socio-demographic data of the participant and recorded in a card-created ad doc (anonymous and coded); in addition, four tests were administered to the older adult. First, the Yesavage Depression Scale (YDP) was used to screen the emotional status of the subjects and to verify that they could participate since one of the exclusion criteria was to be under psychiatric treatment or with depression.

Before implementing the online protocol, pilot tests were conducted with the population of interest to adapt the instruments from the in-person to the online modality. The cognitive assessment instruments used were the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA), the Cacho Version Clock Drawing Test (CDT), and the Word Accentuation Test (WAT). The Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) and the Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (IDDD) were used to obtain data about the participants from the perspective of the key informant (family member or caregiver).

The selection of instruments in this screening protocol was based on the goal of integrating multiple complementary sources of information. The MoCA provides a concise yet comprehensive measure of global cognition. The Cacho Clock Test, administered under both command and copy conditions, enables the calculation of the Improvement Pattern (IP)—the discrepancy between unaided and guided performance. This index has shown sensitivity to early cognitive impairment, particularly in prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease, even in cases where global scores remain within normal limits [17,20]. While the command version involves constructing the clock without a model, the copy version relies on visuo-constructive ability. Their comparison adds diagnostic value to the screening process.

Similarly, the IQCODE and IDDD offer distinct but complementary perspectives. The IQCODE captures perceived cognitive decline over time as reported by a close informant, while the IDDD provides a structured assessment of current functioning in daily activities. Together, these instruments support a comprehensive and ecologically valid screening strategy for early cognitive vulnerability.

The MoCA was found to be valid for the detection of MCI in the Spanish population, with significantly good internal consistency (Cronbach’s a: 0.772), high reliability (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.846; p < 0.01), and high-reliability test-retest reliability: 0.922; p < 0.001. The MoCA was also effective and valid for detecting MCI (AUC ± 0.903) and early dementia (AUC ± 0.957). The cut-off points that would indicate MICI or early-stage dementia were: <21 and <20 respectively, with sensitivity percentages of 75% and specificity of 85% for MCI, whereas in early-stage dementia the sensitivity is 90% and 86% for MCI [20]. In our study, the ICC between MoCA and CDT was 0.64, while for WAT/MoCA it was 0.810 [21].

For this study, we used the Cacho version of the Clock Drawing Test (CDT), which includes the drawing of a clock on command (CDTcm) and its comparison to the drawing of a copied clock (CDTcp), the Cacho version of the CDT has been validated in the Spanish population with significant sensitivity and specificity indices [22], and which proposes a cut-off point where a score < 6 out of 10 is considered indicative of MCI. As for the WAT, it has not been previously validated in the Spanish population, but it has shown good internal values (alpha = 0.841) and a reliability of r = 0.908 when converting the score when comparing the scores obtained in subjects when administering the WAIS-IV scales in the Ecuadorian population (r = 0.827) [23].

Regarding the use of tele-neuropsychology in this study, a rigorous approach was applied following the tele-neuropsychology guidelines proposed by the APA [24] during the COVID-19 pandemic. While in the face-to-face format, they were administered in writing, in the virtual format, the tests were presented by the examinee in front of the camera to provide the necessary screenshots of the task required of the participants.

The transition from in-person to tele-neuropsychology was challenging. During the virtual sessions, technical difficulties arose that required immediate resolution. To overcome these difficulties, specific communication protocols were established. In cases where the connection or platform experienced problems, a phone call was used to continue the session without interruption. In addition, in some cases, family members present at the patient’s location provided technical assistance to ensure the uninterrupted flow of the sessions.

After the subjects were evaluated, key informants were interviewed using two instruments. To assess indicators of cognitive decline in the subjects, the IQCODE questionnaire was used, which asked informants about their perceptions of changes in intellectual functioning that the patients had experienced in recent years. The IQCODE has been validated in the Spanish-speaking population to determine the functional status of individuals before and after stroke [25]; for this study, we used the cutoff originally proposed by Jorm, according to which a score > 57 would indicate probable MCI, as this score has previously been shown to have high internal reliability in the general population (alpha = 0.95) and reasonably high test-retest reliability over 1 year in the dementia sample (r = 0.75). The IQCODE total score and each of its 26 items have been used to discriminate cognitive states between healthy populations and populations with dementia [26].

Regarding the level of autonomy, the IDDD interview was applied to informants because previous studies have shown that people with MCI and early dementia are affected to varying degrees in their initiative and performance in instrumental life activities, also highlighting the importance of social activities for a sense of well-being [27]. In this regard, Cattaneo et al. [28] have presented an adaptation and validation of the IDDD for the Spanish-speaking population, obtaining high internal consistency (a = 0.985) and reproducibility (interclass correlation coefficient = 0.94).

The correlations were significant (r = 0.81), showing that the IDDD in its Spanish version is a reliable version of the original IDDD, and can be used effectively in the Spanish population for the early stages of dementia and its follow-up. Therefore, it was used for this study with the same reference cut-off points (33–36 normal, 37–40 MCI indicators, >40 < MCI/dementia indicators in different degrees of severity). The scale’s factor structure was also confirmed in MCI and AD populations.

2.3. Procedures

Due to the confinement situation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the application of the protocol was carried out according to the preference and circumstances of each participating subject, with two options available: face-to-face or online modality. In the first case, the consultation was carried out through a videoconferencing application, consisting of an evaluation with the subject (30–35 min), in which the cognitive state was assessed with the instruments described above. Then, in the second part (15 min), the key informant interview was conducted. For the online assessments, the adapted versions of the MoCA, CDT, and WAT were used, as well as the IQCODE and IDDD, always following the guidelines suggested by the APA [24] for adapting instruments used in the face-to-face assessment to the online modality.

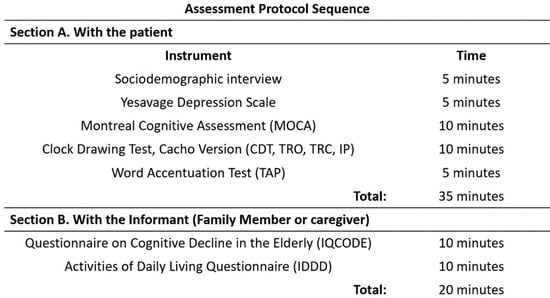

The face-to-face evaluation and the order in which the protocol was administered were the same and followed the same sequence as the online evaluation. (Figure 1). Before the assessment, all subjects completed the informed consent form. At the end of the process, they received a report on their cognitive status with appropriate recommendations for referral to other levels of care according to their results, as specified in the protocol of the unit services.

Figure 1.

Assessment protocol sequence.

Therefore, it should be emphasized that the protocol used in this study does not allow the diagnosis of MCI but is used to explore indicators of vulnerability (previous stage from a prodromic MCI—early stage dementia). As described, this screening was not carried out solely based on the MoCA score, but with the full set of tests and sources of information (older adult and key informant). This is an important aspect to highlight as many of the studies like the one that we are presenting here are based on only one source, usually the older adult, ignoring the key fact that relevant data may be forgotten due to the amnesic problem, hence the importance of the information corroborated with the informant (relative or caregiver).

2.4. Data Analysis

All results presented in this study were obtained using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 28 statistical analysis package. The significance level used for the analyses was p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, as appropriate, which is indicated in each table.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Leven test were used to test the distribution and homogeneity of the cognitive variables before statistical analysis. The results of these analyses were significant, indicating that each of the cognition status variables under study had a normal distribution and was suitable for the parametric statistical analyses.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and health variables defining the sample. Most of the subjects were women (76.4%), with higher education (42.6%) or lower education (57.5%), living alone (62.2%), without cardiovascular risk (81.1%), diabetes (87.8%), or hypertension (77%); most of them did not take any medication (78.4%), or consume alcohol (81.1%) or tobacco (95.3%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and health variables.

Table 2 shows the results obtained on the different indicators of MCI of the participants from the instruments used: MoCA, CDTcm, CDTcp, IP, and the WAT, as well as the IQCODE and the IDDD.

Table 2.

Descriptive data of the variables evaluated.

The statistical analysis (Pearson correlation) performed to test the first objective of this study shows the relationship between the variables associated with cognitive impairment. The results show a moderate and positive correlation between MoCA, CDTcm (0.743), and CDTcp (0.587), which confirms that both the general cognitive assessment provided by the screening test and the additional measures (visual-constructive aspects and cognitive reserve) provide a consistent profile of the participant’s risk situation or lack thereof.

Since the MoCA scores appear to have a large standard deviation, Table 3 shows the range of scores, by educational intervals.

Table 3.

Range of scores by educational intervals.

On the other hand, moderate and negative values were found between the MoCA and the IDDD questionnaire (−0.456 p-value 0.001) and IQCODE (−0.484 p-value 0.001), indicating that the results of the participant’s assessment were consistent with the key informant’s observations.

Finally, we highlight the negative correlation obtained between the CDTcm, IP, IQCODE, and IDDD scores. As can be seen in Table 4, the most relevant associative key for the deterioration in the protocol is the correlation between the performance in the CDTcm and the IP index (−0.803) resulting from comparing the drawing of the CDT cm and the CDTcp.

Table 4.

CDTcm/IP correlation.

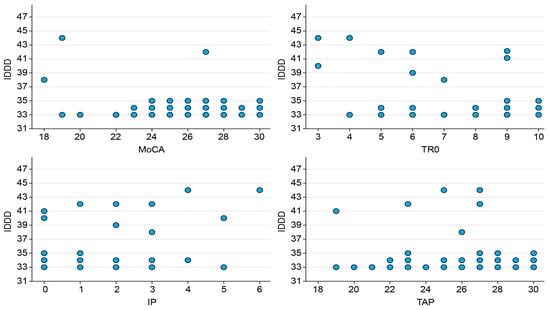

Also important is the association of this index with the cognitive reserve assessed with the WAT (−0.417). Of lesser magnitude, but very significant, is the correlation between cognitive status according to MoCA, IP, and WAT with the key informant’s assessment of the patient’s cognitive decline (IQCODE 0.395) and autonomy (IDDD 0.260), in this particular case the correlation between IQCODE (cognitive decline), IDDD (autonomy), and CR is negative (−0.390), meaning that, within the participants the less cognitive reserve they seem to have more level of dependency, loss of autonomy and cognitive decline was reflected in the daily activities according to the key informant. These aspects are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Patients’ cognitive status.

Regarding the second objective, the statistical analyses performed (Student’s t-test) show that the type of evaluation modality (face-to-face or online) does not significantly alter the results in any of the variables analysed. Therefore, we can say that the evaluation results are not influenced by the modality chosen (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results according to modality assessment.

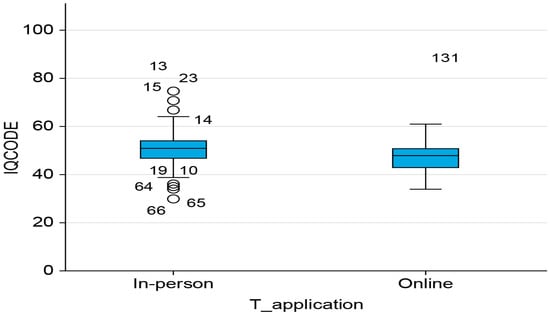

It should be noted that significant differences in the IQCODE scores were found only in the in-person modality (t = 2.050 and p-value = 0.042). Informants of participants who attended in person had a higher perception of their relative’s cognitive impairment (50.84 and SD: 8.74) than those who attended online (48.18 and SD: 6.95). Data are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Box plot on assessment modality and cognitive decline.

Finally, an attempt was made to clarify the variables associated with cognitive impairment that could be predictors of cognitive impairment. For this purpose, a regression was performed with the predictor variables CDTcm, CDTcp, IP, WAT, IQCODE, and IDDD, with the criterion (dependent) variable MoCA. Of these, only the statistical solution found includes the variables WAT, IQCODE, and IDDD as part of a stable model (Y’ = 9.302 − 0.317 × 1 − 0.017 × 2 + 0.128 × 3, (2: 0.516 and F (p-value:) 51.273 (<0.001)) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Linear regression on MoCA, IQCODE, and IDDD.

Thus, sensitivity in detecting suspected MCI, according to the model results, would fall on cognitive reserve as it relates to the older adult measure and the two key informant measures (cognitive status and level of autonomy).

In addition, given that the sample has a high level of education, subsample analyses were performed in a split group for face-to-face and virtual administration for low and high education. This was carried out to see the differences in performance between the education groups. We used a multivariate general linear model in which we included as dependent variables the variables analysed in the study and as independent variables the level of education (low and high) and the type of application of the workshop (face-to-face and online).

First, we checked the assumption of homoscedasticity in the multivariate vector using the box test (p = 0.000 < 0.05), which was significant; therefore, the assumption of homoscedasticity is not fulfilled for the multivariate manager. On the other hand, Leven’s Contrast was calculated for the variables of the study and significant values were found for some of the variables, so this assumption is not met for CDTcm (p = 0.040 < 0.05), CDTcp (p = 0.037 < 0.05), and WAT (p = 0.001 < 0.05).

However, given the balanced size of the groups (63 high education subjects and 85 low education subjects; 74 face-to-face subjects and 74 online subjects), we can assume that the test is robust to the violation of this assumption, so we present below the results obtained from the multivariate general linear model.

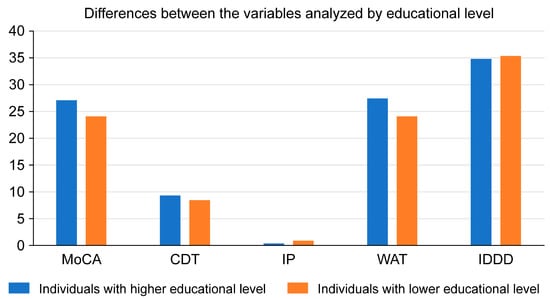

Significant differences were found only in the variable education (Pillai trace p = 0.001 < 0.05), with an observed power of 0990. No significant differences were found in the assessment modality or the interaction between the two variables. In the tests of between-subjects effects, we found differences in the variables MOCA, CDTcm, IP, WAT, and IQCODE as a function of the variable education (Table 7).

Table 7.

Education variables.

Subjects with a high level of education (university and high school) score higher on the MoCA and CDTcm than those with a low level of education (primary and secondary school) have lower scores in the same tests. Among key informants, those who are key informants of highly educated participants score higher on the WAT and lower on the IDDD than those who are key informants of participants with lower education.

Recent work confirms the role of cognitive reserve (CR) in cognitive and motor function [29], a relationship that is justified as an underlying mechanism, as an opening to experience, to mitigate cognitive decline [29]. In the preclinical stage of dementia or MCI, it is essential to develop strategies that lessen the consequences of deterioration in cellular homeostasis, brain functions, and behavioural/cognitive patterns [30].

Increased CR counteracts age-related changes in neural activity, as noted in previous studies [31]. This pattern of neural activity is characteristic of young adults in whom interhemispheric asymmetry does not occur. This may be related to active coping strategies and lower perceived stress in individuals with greater cognitive reserve [31]. Studies of the brain mechanisms underlying CR [32] also explain how a superior ability to flexibly adjust activation as the cognitive demand of the task increases (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cognitive reserve underlying.

4. Discussion

Given the situation when COVID-19 struck, one of the main measures to mitigate the spread of the virus in the elderly population was confinement. However, this significantly reduced opportunities for social interaction and autonomy, as well as the detection of possible cases of incipient cognitive impairment. Given that an active and autonomous life can ensure better cognitive functioning and greater cognitive neuroplasticity in the elderly, the restrictions on mobility and isolation resulting from the pandemic have had the opposite effect [16].

In this study, education was categorised into two groups: low education (primary and secondary) and high education (high school and university), according to the structure of the Spanish education system. This classification allowed us to identify statistically significant differences in both cognitive performance and informant-reported measures, consistent with existing literature on the role of education in cognitive reserve and the onset of MCI. However, we acknowledge that this grouping may differ from classifications used in other countries, where higher education is typically defined as university level or above. This methodological distinction should be taken into account when interpreting and comparing our findings internationally.

Regarding the first objective of this study, the results obtained support the clinical and diagnostic interest of the screening protocol, due to the relationship between the variables measured. Thus, the MOCA is a more valid screening tool than the Mini-Mental or other screening tests for the assessment of visual-constructive functions (CDTcp), an aspect already pointed out by Aguilar et al. [33]. It is also useful to analyse the concordance with key informants, both in cognitive decline and autonomy (IQCODE and IDDD), a dimension also reflected in previous work [27,34]. And very relevant is the discrepancy index, highlighted in the model of Cacho et al. [17], because of its inverse logic, i.e., the higher the IP, the higher the risk of impairment, in this regard MOCA’s scores are less sensitives with this population.

Regarding the correlations between the MoCA and the CDTcm/cp, the results support the usefulness of using both tests, which could be repetitive. The CDTcm/cp, offers a complementary and more sensitive perspective than MoCA, allowing a more precise differentiation of cognitive impairment through the IP analysis [17,22].

The contribution of the CR measured with the WAT and correlated to visual-constructive functioning (VFC) is also significant and, as we highlighted in the results, its inverse correlation is very high [11]. This is a consistent aspect of the role that CR plays in modulating vulnerability to decline, both in the population of older adults in a situation of autonomy or institutionalization [27] and in earlier evolutionary stages, along with other psychological factors such as a sense of purpose in life [35]. In addition to the cognitive cues, the Rotterdam study [36] showed that greater cognitive and brain reserve may be protective factors against depressive events in aging.

The added value of the protocol used in this study, which combines the assessment of the older adult with data from the key informant. Regarding the second objective, the results are important to show that the scores are similar regardless of the assessment modality (in-person/online). In this line, with some of the tests used (MoCA or CDTcm/cp), the consistency index in test-retest applications is confirmed by Cattaneo et al. [28].

Only the IQCODE mean is different in the face-to-face modality, which may be due to the greater perceived severity of the participant’s cognitive status by the key informants. The face-to-face choice would also be justified by the consequences derived from the limitations of on-site access to the different levels of the health system, with the prevalence of telephone consultations in primary or specialized care, which would explain the opportunity offered by this resource open by the dual modality at the choice of users.

Overall, the results would confirm the validity of the protocol regardless of the application modality. The innovation in this work is the evidence for other indicators (WAT, IQCODE, IDDD) for which there are no specific results in online applications, but which have demonstrated their predictive usefulness in traditional and online assessments [19,25,26].

Finally, the regression models used indicate that CR (WAT) would be most relevant for discriminating potential cases of MCI that could later evolve into dementia. On the second point, our work brings an element of innovation, given that the accumulated evidence on the involvement of key informants in screening tests in a combined manner is not so abundant. In most cases, epidemiologic data are based on one or another source but not on both (patients/key informants).

In our work, given that it was not possible to use biomarker indicators, we opted for the use of the WAT as a direct measure of CR, corroborated in previous research, due to its high correlation with tests of fluid and crystallized intelligence (Wechsler scales).

We are aware that a larger sample would help us to obtain more meaningful results and avoid the risk of bias or generalisation in the results. However, as explained in the modified version of our text, the population served is based on requests from residents of the city over the age of 60.

Therefore, it is a random sample (it is not stratified because there are no previous categories and it is formed until the number of participants in each of them is found) in this process; the research team does not have any capacity to select the sample or knowing which of them have cognitive impairment risk at the first moment. For this reason, we have expanded this consideration in the conclusions as one of the limitations of our study, but despite this, we believe that, being an exploratory study with this sample, we have obtained important results that may be useful for people interested in this topic.

It should be noted, however, that not all the literature is consistent with these findings. For example, Babiloni et al. [37] combined memory measures and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a large study of middle-aged Dutch adults followed for 12 years. The results suggest that a higher CR (with indicators of education and reading tests) is a better predictor of risk of impairment than the intracranial volume used in many studies.

By establishing the correlation between variables, it has been possible to identify critical variables of MCI in a way that does not represent the risk of contagion with the COVID-19 virus by conducting it online during the pandemic. In addition, having an alternative tool for early detection helps to preserve CR and delay the progression of MCI to dementia in older adults [38,39].

5. Conclusions

The implementation of this protocol in any of its modalities can solve the problem of late diagnosis of dementia, which is usually detected in very advanced stages of the disease; the combined sources of evaluation (older adults and key informants) provide significant clues that give greater certainty to the screening task.

In addition, the different modalities, face-to-face or online, do not reflect changes in terms of prognostic value. In a situation such as the pandemic period, having a tool with this potential for use in cases of contact deprivation or geographical distance (rural areas) is a highly relevant contribution.

The limitations of the present study are, first, related to the nature of the study, since, as a cross-sectional study, the results only allow us to reflect a glimpse of a specific evolutionary moment. It would have increased the explanatory power if a longitudinal design had been used to determine the evolutionary pattern of risk situations. We are currently conducting a longitudinal follow-up of a significant portion of the sample used, which will allow us to determine stability or change according to the typified risk assessment.

The second limitation is the strength of a screening study that does not allow for formal diagnosis. This limitation does not allow confirmation of the diagnosis of MCI or the specific subtype of the existing typology (amnestic, multidomain, etc.).

Despite this limitation, and as argued by the Cognitive Decline Group of the European Innovation Partnership for Active and Healthy Ageing [40], early detection is necessary, even if screening cannot reflect the complexity inherent in a complex clinical entity and an uneven evolutionary process in terms of the parameters involved (cognitive, executive, and functional performance).

It should be noted that we have followed the considerations of previous studies to avoid contamination by false positives and it would be appropriate to expand the sample size with a representation of older adults in residences to determine differences in the parameters evaluated. Samples should also include older adults with less healthy profiles or more vulnerable socio-cultural and economic conditions. In addition to using neuropsychological screening tests, the protocol should be extended to include neuroimaging techniques or biological markers [30,41] that provide greater discriminative power.

Consistent with what we said about using the protocol in different countries, the accumulation of data will allow for generalization and particularization according to cross-cultural cues to expand our research. This future possibility is supported in the present work by the originality of the methodological approach (mixed assessment of MCI risk with the older adult and the key informant), technological (use of procedures based on telepsychology), psychometric (evidence of the validity of the tests regardless of the modality), and clinical (relationship between cognitive performance variables or the role of cognitive reserve as a modulator of the process).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.-C., R.G.-G., L.D.L.T., J.C.G. and P.P.F.; data curation, A.S.-C., B.P.-V., L.D.L.T. and P.P.F.; formal analysis, A.S.-C., B.P.-V., L.D.L.T. and P.P.F.; funding acquisition, A.S.-C.; investigation, A.S.-C., L.D.L.T. and P.P.F.; methodology, A.S.-C., B.P.-V., L.D.L.T. and P.P.F.; project administration, A.S.-C., L.D.L.T. and P.P.F.; resources, A.S.-C., R.G.-G., L.D.L.T., J.C.G. and P.P.F.; software, A.S.-C. and B.P.-V.; supervision, A.S.-C.; validation, A.S.-C., L.D.L.T. and P.P.F.; visualization, A.S.-C.; writing—original draft, A.S.-C., L.D.L.T. and P.P.F.; writing—review and editing, A.S.-C., L.D.L.T. and P.P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has been funded within the framework of the agreement code: 32/2025/SUNO between the City of Salamanca and the Pontifical University of Salamanca (2020–2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Pontifical University of Salamanca for the favourable report on the performance of this work (registered(ei-MEMO+AYsal 12/03/2021)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| MCI-amnestic | Mild cognitive impairment-amnestic |

| MCI-Non amnestic | Mild cognitive impairment non-amnestic |

| NIA-AAA | National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test |

| CT | Clock Test |

| APA | American Psychological Association |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Revision |

| ICD-11 | International of Diseases 11th Revision |

| BPA | Boston Process Approach |

| DLAs | Daily living activities |

| ICTs | Information and communication technologies |

| SMC | Subjective Memory Complaint |

| MU | Memory Unit |

| UPSA | Pontifical University of Salamanca |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| YPD | Yesavage Depression Scale |

| CDT | Clock Drawing Test Cacho Version |

| WAT | Word Accentuation Test |

| IQCODE | Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly |

| IDDD | Interview for Deterioration in Daily Living in Dementia |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| CDTcm | Clock Drawing Test Cacho Version on Command |

| CDTcp | Clock Drawing Test Cacho Version copied |

| WAIS-IV | Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale 4th Edition |

| IP | Improvement Pattern of the Clock Drawing Test Cacho Version |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| CR | Cognitive reserve |

| CDTcm/cp | Clock Drawing Test Cacho version on command and copied |

| VFC | Visual Constructive Function |

References

- Borrás Blasco, C.; Viña Ribes, J. Neurofisiología y envejecimiento. Concepto y bases fisiopatológicas del deterioro cognitivo. Rev. Española Geriatría Y Gerontol. 2016, 51, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancino, M.; Rehbein, L. Factores de riesgo y precursores del Deterioro Cognitivo Leve (DCL): Una mirada sinóptica. Ter. Psicólogica 2016, 34, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S.; Rosa-Neto, P.; Morais, J.A.; Webster, C. World Alzheimer Report 2021, Abridged Version: Journey Through the Diagnosis of Dementia; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R.M.; Iverson, G.L.; Cernich, A.N.; Binder, L.M.; Ruff, R.M.; Naugle, R.I. Computerized neuropsychological assessment devices: Joint position paper of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology and the National Academy of Neuropsychology. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2012, 26, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marra, D.E.; Hamlet, K.M.; Bauer, R.M.; Bowers, D.; Williamson, J. Validity of teleneuropsychological assessment in older patients with cognitive disorders. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 35, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Andrews, J.S.; Beach, T.G.; Buracchio, T.; Dunn, B.; Graf, A.; Hansson, O.; Ho, C.; Jagust, W.; McDade, E.; et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 5143–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dubois, B.; Villain, N.; Schneider, L.; Fox, N.; Campbell, N.; Galasko, D.; Kivipelto, M.; Jessen, F.; Hanseeuw, B.; Boada, M.; et al. Alzheimer Disease as a Clinical-Biological Construct-An International Working Group Recommendation. JAMA Neurol. 2024, 81, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lezak, M.D.; Howieson, D.B.; Bigler, E.D.; Tranel, D. Neuropsychological Assessment, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- González Martínez, P.; Oltra Cucarella, J.; Sitges Maciá, E.; Bonete López, B. Revisión y actualización de los criterios de deterioro cognitivo objetivo y su implicación en el deterioro cognitivo leve y la demencia. Rev. de Neurol. 2021, 72, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2016, 22, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldberg, C.; Tartaglini, M.F.; Hermida, P.D.; Moya-García, L.; Licenciada-Caruso, D.; Stefani, D.; Somale, M.V.; Allegri, R. El rol de la reserva cognitiva en la progresión del deterioro cognitivo leve a demencia: Un estudio de cohorte. Neurol. Argent. 2021, 13, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C.; Smith, G.E.; Waring, S.C.; Ivnik, R.J.; Tangalos, E.G.; Kokmen, E. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch. Neurol. 1999, 56, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempermann, G. Embodied Prevention. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 841393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denney, D.A.; Prigatano, G.P. Subjective ratings of cognitive and emotional functioning in patients with mild cognitive impairment and patients with subjective memory complaints but normal cognitive functioning. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2019, 41, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amieva, H.; Retuerto, N.; Hernandez-Ruiz, V.; Meillon, C.; Dartigues, J.F.; Pérès, K. Longitudinal Study of Cognitive Decline before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the PA-COVID Survey. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2022, 2, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Cabaco, A.; De La Torre, L.; Alvarez Núñez, D.N.; Mejía Ramírez, M.A.; Wöbbeking Sánchez, M. Tele neuropsychological exploratory assessment of indicators of mild cognitive impairment and autonomy level in Mexican population over 60 years old. PEC Innov. 2023, 2, 100107. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772628222000929 (accessed on 4 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cacho, J.; García-García, R.; Fernández-Calvo, B.; Gamazo, S.; Rodríguez-Pérez, R.; Almeida, A.; Contador, I. Improvement Pattern in the Clock Drawing Test in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. Neurol. 2005, 53, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, A.G.; Calero, M.D. Predictores del deterioro cognitivo en ancianos [Predictors of cognitive decline in the elderly]. Rev. Española Geriatría Y Gerontol. 2009, 44, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; Jacomb, P.A. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): Socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychol. Med. 1989, 19, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhann, R.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Fonseca, R.P.; Stern, Y. Editorial: Cognitive reserve and resilience in aging. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1120379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, M.L.; Ferrándiz, M.H.; Garriga, O.T.; Nierga, I.P.; López-Pousa, S.; Franch, J.V. Validación del Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): Test de cribado para el deterioro cognitivo leve. Datos preliminares. Alzheimer Real. Investig. Demenc. 2009, 43, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Cacho, J.; García-García, R.; Arcaya, J.; Vicente, J.L.; Lantada, N. Una propuesta de aplicación y puntuación del test del reloj en la enfermedad de Alzheimer [A proposal for application and scoring of the Clock Drawing Test in Alzheimer’s disease]. Rev. Neurol. 1999, 28, 648–655. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluck, G.; Almeida-Meza, P.; Andrea, G.-L.; Muñoz-Ycaza, R.A.; Trueba, A. Estimación de la Función Cognitiva Premórbida con el Test de Acentuación de Palabras. Estimation of Premorbid Cognitive Function with The Word Accentuation Test. Rev. Ecuat. Neurol. 2017, 26, 226–234. [Google Scholar]

- Bilder, R.M.; Postal, K.S.; Barisa, M.; Aase, D.M.; Cullum, C.M.; Gillaspy, S.R.; Harder, L.; Kanter, G.; Lanca, M.; Lechuga, D.M.; et al. Inter Organizational Practice Committee Recommendations/Guidance for Teleneuropsychology in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 35, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, J.M.; Gonzalez-Montalvo, J.I.; Bermejo, F.; Del-Ser, T. The screening of mild dementia with a shortened Spanish version of the “Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly”. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 1995, 9, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-García-Patino, R.; Benito-León, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Pastorino-Mellado, D.; García García, R.; Ladera-Fernández, V.; Vicente-Villardón, J.L.; Perea-Bartolomé, M.V.; Cacho, J. Memory and Executive Dysfunction Predict Complex Activities of Daily Living Impairment in Amnestic Multi-Domain Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 75, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, M.G.; Ruíz de Sánchez, C.; Gutiérrez, S.; Ortiz, A.; Samper-Ternent, R.; Cano Gutiérrez, C.A. Relación Entre Deterioro Cognoscitivo y Actividades Instrumentales de la Vida Diaria: Estudio SABE-Bogotá, Colombia. 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10554/49117 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Cattaneo, G.; Solana-Sánchez, J.; Abellaneda-Pérez, K.; Portellano-Ortiz, C.; Delgado-Gallén, S.; Alviarez Schulze, V.; Pachón-García, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Tormos, J.M.; Pascual-Leone, A.; et al. Sense of Coherence Mediates the Relationship Between Cognitive Reserve and Cognition in Middle-Aged Adults. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 835415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, J.; Gerardo, B.; Santana, I.; Simões, M.R.; Freitas, S. The Assessment of Cognitive Reserve: A Systematic Review of the Most Used Quantitative Measurement Methods of Cognitive Reserve for Aging. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 847186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yener, G.G.; Emek-Savaş, D.D.; Lizio, R.; Çavuşoğlu, B.; Carducci, F.; Ada, E.; Güntekin, B.; Babiloni, C.C.; Başar, E. Frontal delta event-related oscillations relate to frontal volume in mild cognitive impairment and healthy controls. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2016, 103, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wöbbeking-Sánchez, M.; Bonete-López, B.; Cabaco, A.S.; Urchaga-Litago, J.D.; Afonso, R.M. Relationship between Cognitive Reserve and Cognitive Impairment in Autonomous and Institutionalized Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaco, A.S.; Sánchez, M.W.; Mejía-Ramírez, M.; Urchaga, D.; Castillo-Riedel, E.; Bonete-López, B. Mediation effects of cognitive, physical, and motivational reserves on cognitive performance in older people. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1112308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Navarro, S.G.; Mimenza-Alvarado, A.J.; Palacios-García, A.A.; Samudio-Cruz, A.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L.A.; Ávila-Funes, J.A. Validez y confiabilidad del MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) para el tamizaje del deterioro cognoscitivo en méxico. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2018, 47, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüera Ortiz, L.F.; García-Ribas, G.; Jordano Luna, F.; Porras Álvarez, M.C.; Sánchez Marcos, N.; Soler López, B. Usefulness of Community Pharmacy for Early Detection of Cognitive Impairment in Older People Using the IQ-CODE Questionnaire. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 10, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, J.R.; Martel, F.; Borges, N.; Araújo, J.M.; Keating, E. Folates and aging: Role in mild cognitive impairment, dementia and depression. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 22, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.A.; Kieboom, B.C.T.; Brouwer, W.P.; Brusselle, G.; Chaker, L.; Ghanbari, M.; Goedegebure, A.; Ikram, M.K.; Kavousi, M.; de Knegt, R.J.; et al. The Rotterdam Study. Design update and major findings between 2020 and 2024. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 39, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiloni, C.; Frisoni, G.; Steriade, M.; Bresciani, L.; Binetti, G.; Del Percio, C.; Geroldi, C.; Miniussi, C.; Nobili, F.; Rodriguez, G.; et al. Frontal white matter volume and delta EEG sources negatively correlate in awake subjects with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006, 117, 1113–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrote, F.M.; Brochero, N.N.; Concari, I.A.; García, I.E.; Assante, M.L.; Lucero, C.B. Asociación entre pérdida subjetiva de memoria, deterioro cognitivo leve y demencia. Neurol. Argent. 2017, 9, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega Alonso, T.; Miralles Espí, M.; Mangas Reina, J.M.; Castrillejo Pérez, D.; Rivas Pérez, A.I.; Gil Costa, M.; Maside, A.L.; Anton, E.A.; Alonso, J.E.L.; Gll, M.F. Prevalencia de deterioro cognitivo en España. Estudio Gómez de Caso en redes centinelas sanitarias. Neurología 2018, 33, 491–498. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0213485316302171 (accessed on 24 January 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolo, J.; Holland, C.; O’Connell, M.D.; Feeney, J.; Tabares-Seisdedos, R.; Tadros, G.; Campos, E.; Santos, N.; Robertson, D.A.; Marcucci, M.; et al. Mild cognitive decline. A position statement of the Cognitive Decline Group of the European Innovation Partnership for Active and Healthy Ageing (EIPAHA). Maturitas 2016, 83, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fide, E.; Yerlikaya, D.; Güntekin, B.; Babiloni, C.; Yener, G.G. Coherence in event-related EEG oscillations in patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Cogn. Neurodyn 2023, 17, 1621–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).