Characteristics of Older Adults Associated with Patient–Provider Communication About Health Improvement in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Population

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

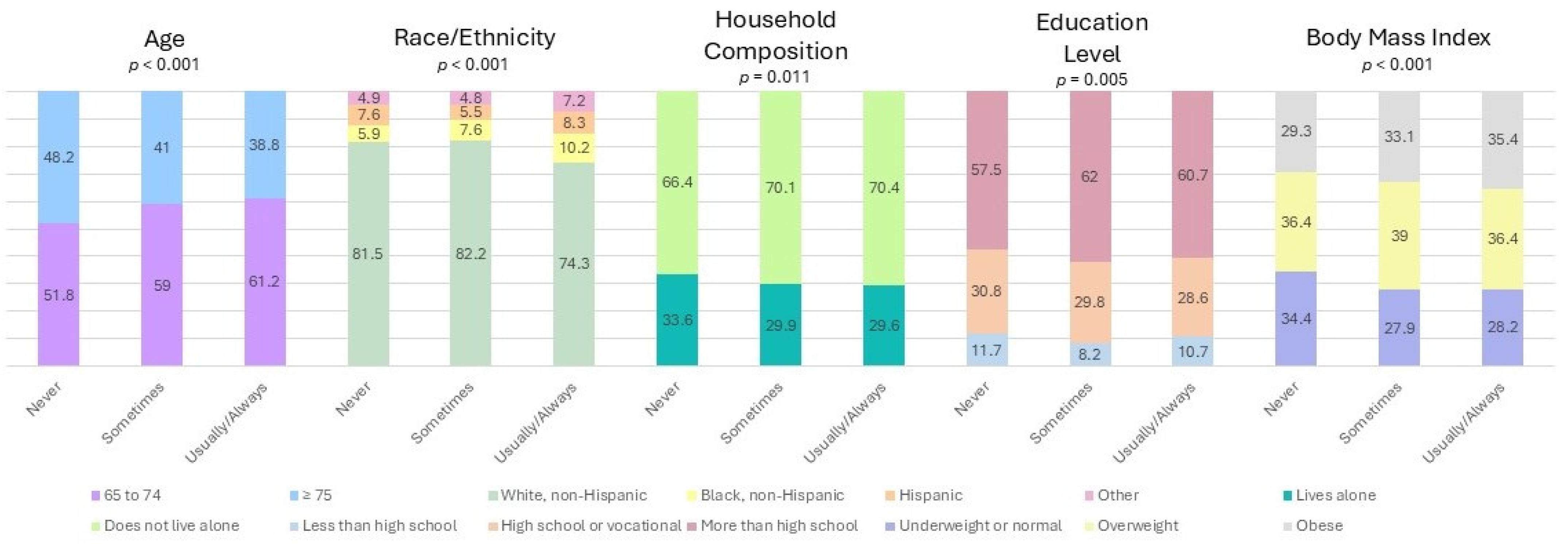

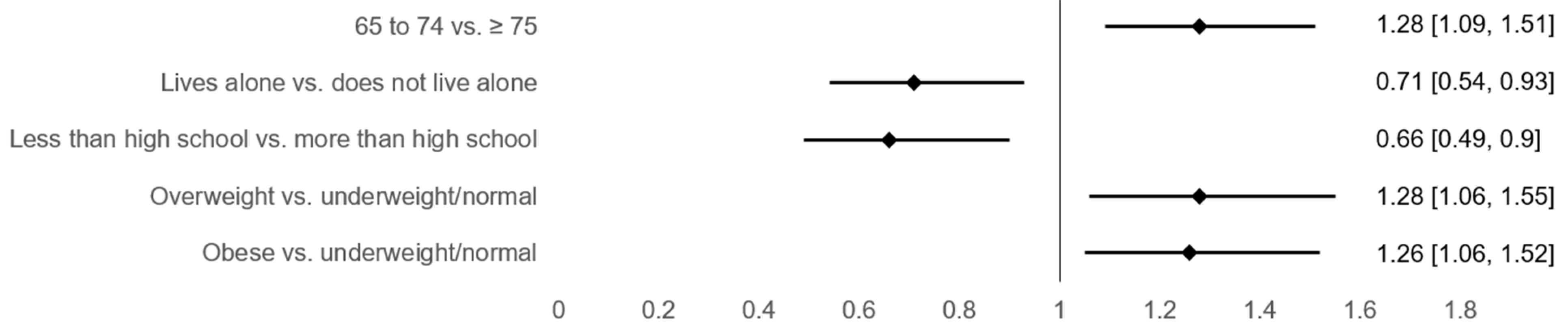

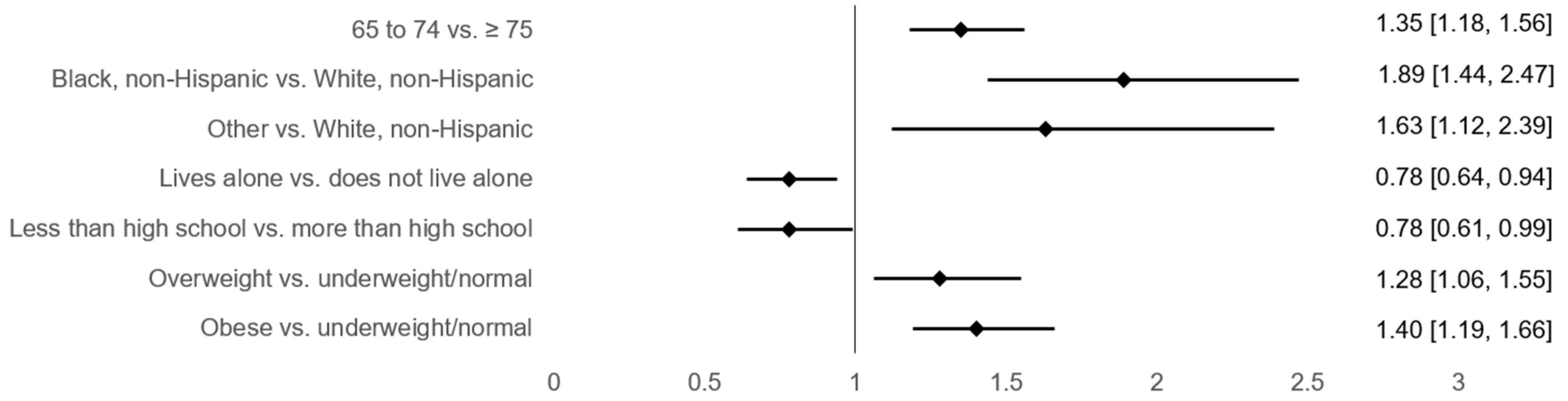

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDM | Shared decision making |

| MCBS | Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey |

| PUF | Public Use File |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

References

- Anderson, E.B. Patient-centeredness: A new approach. Nephrol. News Issues 2002, 16, 80–82. [Google Scholar]

- Constand, M.K.; MacDermid, J.C.; Dal Bello-Haas, V.; Law, M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, N.; Moser, R.P.; Breslau, E.S.; Chou, W.S. Predictors of Patient-Centered Communication among U.S. Adults: Analysis of the 2017–2018 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekonen, A.; Eloranta, S.; Stolt, M.; Virolainen, P.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Measuring patient empowerment—A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, D.; Piper, S. Patient empowerment within a coronary care unit: Insights for health professionals drawn from a patient satisfaction survey. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2007, 23, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funnell, M.M.; Anderson, R.M.; Arnold, M.S.; Barr, P.A.; Donnelly, M.; Johnson, P.D.; Taylor-Moon, D.; White, N.H. Empowerment: An idea whose time has come in diabetes education. Diabetes Educ. 1991, 17, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokes, N.; Lloyd, C.; Girardin, A.L.; Santana, C.S.; Mangus, C.W.; Mitchell, K.E.; Hughes, A.R.; Nelson, B.B.; Gunn, B.; Schoenfeld, E.M. Can shared decision-making interventions increase trust/trustworthiness in the physician-patient encounter? A scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2025, 135, 108705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Durand, M.A.; Song, J.; Aarts, J.; Barr, P.J.; Berger, Z.; Cochran, N.; Frosch, D.; Galasiński, D.; Gulbrandsen, P.; et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: Multistage consultation process. BMJ 2017, 359, j4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusiak, J.; Sarpari, K.; Ma, I.; Mansmann, U.; Hoffmann, V.S. Practical applications of methods to incorporate patient preferences into medical decision models: A scoping review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2025, 25, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, W.D.; Levine, S.A.; Wenger, N.K.; Harold, J.G. Shared decision-making for older adults with cardiovascular disease. Clin. Cardiol. 2020, 43, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, J.P.; Chiu, C.T. Projecting the chronic disease burden among the adult population in the United States using a multi-state population model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1082183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrinou, E.; Hansen, T.B.; Beulens, J.W. Lifestyle factors, self-management and patient empowerment in diabetes care. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26 (Suppl. S2), 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maly, R.C.; Stein, J.A.; Umezawa, Y.; Leake, B.; Anglin, M.D. Racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer outcomes among older patients: Effects of physician communication and patient empowerment. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, N.B.; Fleury, J.; Ward, K.A.; O’Brien, A.M. Empowerment interventions for older adults. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2012, 34, 24–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis-Ajami, M.L.; Lu, Z.K.; Wu, J. US Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions Perceptions of Provider-Patient Communication: Trends and Racial Disparities from MEPS 2013–2019. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 1459–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCBS Public Use File. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Available online: https://data.cms.gov/medicare-current-beneficiary-survey-mcbs/medicare-current-beneficiary-survey-survey-file (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Vissenberg, M.; de Natris, D. De mondigheid van de oudere patient bij de geriater: Een kwalitatief onderzoek naar de mondigheid van oudere patienten in de relatie met de geriater en het effect op de communicatie en de medische behandeling. Tijdschr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 47, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Hou, W.; Li, H. Cognitive Decline Associated with Aging. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1419, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Puerta, L.; Caballero-Bonafe, A.; de-Moya-Romero, J.R.; Martinez-Sabater, A.; Valera-Lloris, R. Ageism and Associated Factors in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 4039–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampubolon, G.; Maharani, A. Trajectories of allostatic load among older Americans and Britons: Longitudinal cohort studies. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Age Group. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/111958 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/105453 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Phibbs, S.C.; Faith, J.; Thorburn, S. Patient-centred communication and provider avoidance: Does body mass index modify the relationship? Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccuti, C.; Swoope, C.; Damico, A.; Neuman, T. Medicare Patients’ Access to Physicians: A Synthesis of the Evidence. KFF. Available online: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-patients-access-to-physicians-a-synthesis-of-the-evidence/ (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Lam, B.C.C.; Lim, A.Y.L.; Chan, S.L.; Yum, M.P.S.; Koh, N.S.Y.; Finkelstein, E.A. The impact of obesity: A narrative review. Singap. Med. J. 2023, 64, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckett, M.K.; Elliott, M.N.; Haviland, A.M.; Burkhart, Q.; Gaillot, S.; Montfort, D.; Saliba, D. Living Alone and Patient Care Experiences: The Role of Gender in a National Sample of Medicare Beneficiaries. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 1242–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.J.; Fang, M.C.; Wannier, S.R.; Steinman, M.A.; Covinsky, K.E. Association of Social Support With Functional Outcomes in Older Adults Who Live Alone. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verlinde, E.; De Laender, N.; De Maesschalck, S.; Deveugele, M.; Willems, S. The social gradient in doctor-patient communication. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, I.; Quelly, S.B.; Chen, Z.; Ng, B.P. Characteristics of Older Adults Associated with Patient–Provider Communication About Health Improvement in the United States. J. Ageing Longev. 2025, 5, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5020014

Wu I, Quelly SB, Chen Z, Ng BP. Characteristics of Older Adults Associated with Patient–Provider Communication About Health Improvement in the United States. Journal of Ageing and Longevity. 2025; 5(2):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5020014

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Ingrid, Susan B. Quelly, Zhuo Chen, and Boon Peng Ng. 2025. "Characteristics of Older Adults Associated with Patient–Provider Communication About Health Improvement in the United States" Journal of Ageing and Longevity 5, no. 2: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5020014

APA StyleWu, I., Quelly, S. B., Chen, Z., & Ng, B. P. (2025). Characteristics of Older Adults Associated with Patient–Provider Communication About Health Improvement in the United States. Journal of Ageing and Longevity, 5(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5020014