1. Introduction

The world’s population is aging due primarily to (1) reduced mortality rates, which have resulted from improved public health, and (2) declining fertility rates [

1]. As populations age, they exhibit an increased prevalence of chronic diseases, such as ischemic heart disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis, sensory impairments, and dementia [

2]. Aging individuals are also more likely to experience multimorbidity (i.e., having multiple chronic conditions simultaneously), which can significantly impact their physical functions and overall quality of life [

3]. In addition to such progressive impairments in various physical functions, aging is associated with a range of psychosocial problems, such as loneliness and depression, e.g., [

4]. These factors diminish the ability of elderly individuals to perform the activities of daily living independently as well as their mental health, leading to poorer quality of life and increased healthcare costs, and often necessitating a move into a care institution [

5].

Institutional care is often perceived as dehumanizing and detrimental to social interactions [

6]. Additionally, relocating can have negative psychological effects on elderly individuals, such as stress, loneliness, and depression [

7]. To address the challenges associated with an aging population, policymakers have promoted initiatives for aging in place rather than moving older adults into specialized housing or care facilities. “Aging in place” refers to the ability to live independently, safely, and comfortably in one’s own home for as long as possible, regardless of age, income, or physical abilities [

1].

Aging in place is a preferred option for elderly individuals because they feel attached to their homes and communities [

8]. When older adults age in place, the independence they experience can help them maintain their sense of identity and contribute to their self-reliance, self-management, and self-esteem [

9]. Thus, aging in place contributes to the overall well-being of older people [

10]. From the perspective of policymakers, aging in place is a better option than institutional care because aging in place is less expensive in the long term [

11].

A variety of factors contribute to successful aging in place, including policies [

12], home environments [

13], communities and neighborhoods [

14], transportation [

15], facilitating physical activity [

16], promoting social interactions [

17], technology [

18], and caregiving [

19]. Hence, aging in place involves multiple disciplines and stakeholders.

Considering the breadth of the topic of aging in place, its multidisciplinary nature, and the variety of stakeholders aging-in-place initiatives involve, a science map of the literature on aging in place offers a number of benefits. First, it enables the identification of key research areas and their evolution over time. Second, it sheds light on interdisciplinary connections, which can point to opportunities for interdisciplinary research and thus lead to new insights and innovations. Third, by providing a comprehensive overview of what has been studied and published, it conserves resources by preventing duplication of effort in various disciplines. Fourth, it makes knowledge more accessible to both new and experienced researchers, facilitating their navigation of vast amounts of information. Lastly, policymakers and stakeholders can use a map of the research landscape to make more informed decisions regarding aging in place.

Various types of literature review, such as systematic, scoping, integrative, and thematic reviews, have been instrumental in mapping the literature on aging in place, e.g., [

20,

21,

22,

23]. For instance, in a scoping review, Pani-Harreman et al. [

23] reviewed 34 articles and identified five major themes in the aging-in-place literature: (1) place, (2) social network, (3) support, (4) technology, and (5) personal characteristics. Similarly, Peek et al. [

22] systematically reviewed the literature and identified 61 articles that addressed factors influencing the acceptance of technologies used to facilitate aging in place.

Literature reviews can offer in-depth analysis, detailed interpretation, and critical evaluation of research findings, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks but, as Donthu et al. [

24] argued, they have several limitations that can restrict their applicability. First, the scope of literature reviews is often narrow and highly specific, which may limit their ability to address broader topics. Second, because the reviewing process is often conducted manually, the number of articles included in literature reviews is typically small (roughly 40–300 articles) to keep the reviewing process manageable. Third, the identification of themes in literature reviews relies on qualitative techniques, which can introduce interpretation bias into the conclusions.

Bibliometric analysis, which relies on quantitative methods, can address the limitations of traditional literature reviews by providing a broad overview of the research landscape and complementing the depth offered by literature reviews. The automated tools and algorithms used in bibliometric analysis can process vast amounts of data quickly, whereas literature reviews are often time-consuming and labor-intensive. As the volume of published research grows, bibliometric analysis remains scalable, whereas literature reviews may become increasingly impractical. Bibliometric analysis uses quantitative data, such as citation counts, the h-index, impact factors, and coauthorship networks, to provide objective measures of the influence and reach of studies. Consequently, bibliometric analysis has gained popularity across various disciplines in recent years, e.g., [

25,

26]. This increased popularity can be attributed to (1) the availability of metadata from databases such as the Web of Science and Scopus, and (2) computer programs like VOSviewer and Gephi, which facilitate bibliometric analysis [

24].

Bibliometric analysis encompasses a variety of techniques, which can be categorized into two major types: performance analysis and science mapping. Performance analysis evaluates the research output and impact of different entities, such as individual researchers, institutions, journals, and countries. Science mapping, also known as scientific visualization, reveals the structural and dynamic aspects of scientific research. Which of these analyses a study uses depends on the research questions of interest.

For example, Oladinrin et al. [

27] conducted a bibliometric analysis of the literature on aging in place, focusing mainly on performance analysis. Although their study included co-occurrence analysis—a component of science mapping—they did not identify themes in their data, which limited the scope of their contribution. In contrast, Seo and Lee’s [

28] bibliometric study of aging in place incorporated both performance analysis and science mapping. However, their analysis was limited to residential environments. Although residential spaces are a crucial aspect of aging in place, it could be argued that the study may not have included other important factors, such as policies and communities. A bibliometric study that included such topics would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the literature.

Thus, considering all the factors that influence aging in place and employing appropriate types of analysis are crucial for creating a comprehensive and meaningful map of the scientific landscape of aging-in-place literature. The gaps in the existing research outlined above prompted the current paper.

This study provides a comprehensive map of the scientific landscape of aging-in-place literature. Accordingly, the study’s research questions are as follows:

What are the leading countries, institutions, and journals in the field of aging in place?

What are the central publications in the citation network of aging-in-place research?

What are the most frequently occurring keywords, and how are they interconnected?

How do these keywords evolve over time?

What are the major themes in the literature on aging in place?

By using a dataset that is larger than that employed by previous studies and by not limiting the scope of the research, this study provides the most comprehensive map of the aging-in-place literature to date.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying Relevant Publications

To identify relevant articles, a search was conducted in the Web of Science Core Collection. This database was selected over others (such as Scopus and OpenAlex) because it yielded more relevant articles and offered more complete metadata (e.g., author-provided keywords). Various forms of the term aging in place (e.g., ageing in place and aging-in-place) were used to search in the title and author-provided-keywords fields. No restrictions were applied to this search (i.e., regarding time, geography, or document type) other than English as the document language.

The search, conducted in July 2024, yielded 3240 records published between 1908 and 2023. Some of these records were unrelated to the topic of aging in place. To streamline the review process, we did not manually screen the records for relevance. Instead, we used VOSviewer 1.6.20, a bibliometric software tool developed by van Eck and Waltman [

29], to identify relevant papers and potential outliers. This automated method made the review process more manageable by eliminating the need for manual screening of all identified records.

VOSviewer 1.6.20 [

29] provides five analysis methods for determining the relatedness of items (e.g., keywords, countries, and papers): (1) coauthorship analysis, (2) co-occurrence analysis, (3) citation analysis, (4) bibliometric coupling analysis, and (5) co-citation analysis. For an overview of these bibliometric-analysis techniques and examples of each, see Donthu et al. [

24]. The current paper used citation analysis and co-occurrence analysis, which the following section explains.

2.2. Data Analysis

To identify the leading countries, institutions, and journals, three metrics were used: (1) total publications (TP), (2) total citations (TC), and (3) the average impact of each publication (TC/TP). Bibliometric studies often use TP as a metric of productivity. TC can indicate scholarly influence or impact. TC/TP is more normalized than TC and allows for comparisons that consider both quality and quantity of output; TC/TP can highlight entities that produced fewer but more influential papers. Using these metrics, the leading countries, institutions, and journals were ranked.

Citation analysis was used to determine the leading publications in the field of aging in place. In citation analysis, the relatedness of publications is determined based on the number of times they cite each other. This number is called the link count. Accordingly, publications with a higher link count are more central in the citation network than those with lower link counts. Using this method of analysis, outliers were filtered out, because irrelevant publications that found their way into the dataset would not have links with the publications on aging in place. Accordingly, the 20 most central publications in the citation network of aging in place were ranked.

For keyword analysis, five types of analysis were performed: (1) identifying the most frequently occurring keywords, (2) examining temporal variability in keywords, (3) graphical network mapping of keywords, (4) identifying clusters of keywords, and (5) identifying the most frequently occurring keywords in each cluster. Before conducting any of these analyses, the data from the Web of Science were cleaned by creating a thesaurus that enabled the use of one term for multiple forms of the same keyword (e.g., different spellings or singular and plural forms) or concept (e.g., adolescence and adolescent). Some general terms, such as the names of countries and research methods (e.g., literature review), were removed from the analysis.

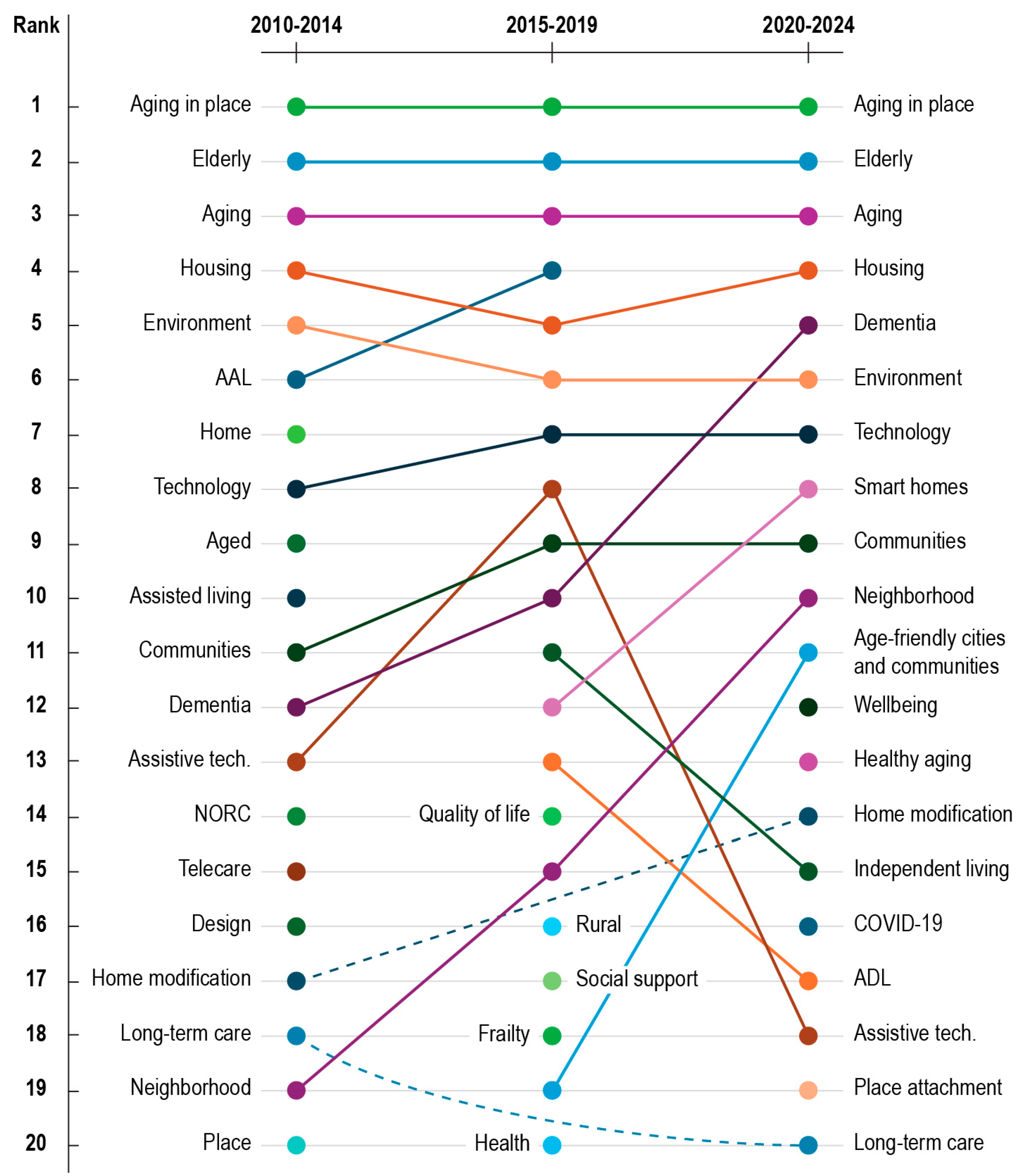

For the examination of temporal variability in keywords, the most frequently occurring keywords in three time periods were examined to identify the evolution of research foci in the literature: 2010–2014, 2015–2019, and 2020–2024. These time periods were selected through several cycles of refinement; these iterations led to the identification of time frames that resulted in a sufficient number of keywords on the topic of aging in place, which enabled a meaningful temporal analysis.

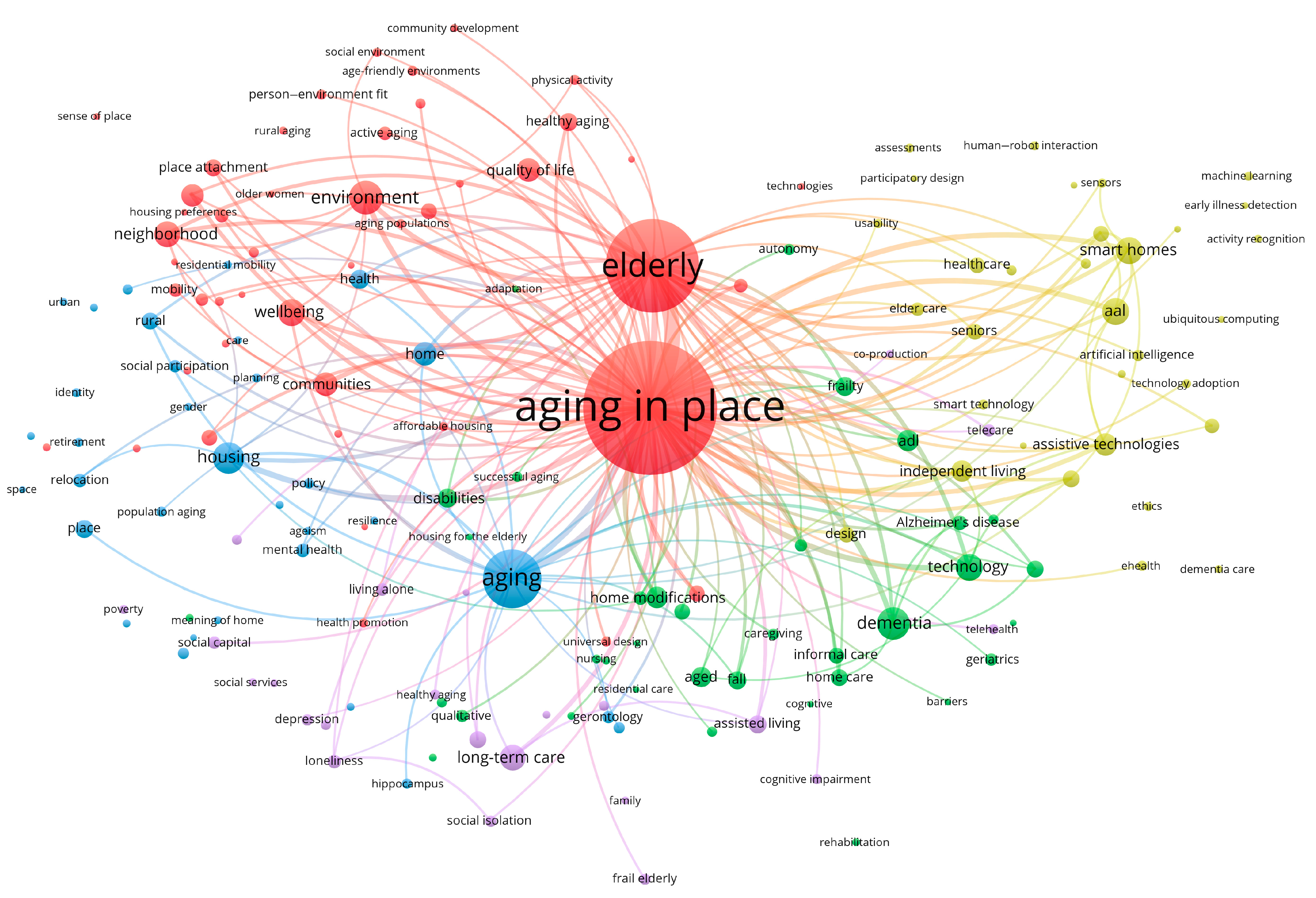

For the graphical network mapping of keywords, co-occurrence analysis was performed in VOSviewer 1.6.20 [

29]. In this paper’s co-occurrence analysis, the unit of analysis was the keywords provided by the authors of the identified publications. The graph consists of nodes and links. The size of the nodes represents the frequency of keyword occurrence, and a line between the nodes indicates that those keywords were mentioned together in a document. The thickness of the lines represents the number of instances of co-occurrence (i.e., the strength of the link); the greater the number of co-occurrences, the thicker the line. To enhance the readability of the diagram, the number of lines shown can be adjusted by focusing on the links with the highest link strengths. Hence, the lack of a visual link between two nodes in the diagram may not necessarily indicate the absence of an actual link. The distance between any two nodes reflects the similarity or relatedness of the items. VOSviewer 1.6.20 [

29] applies a clustering algorithm to the network. This algorithm is based on the idea of maximizing a modularity-based quality function. The algorithm iteratively adjusts the assignment of keywords to clusters to maximize the quality function, resulting in a partition of keywords into clusters. Different clusters are indicated using different colors, making it easier to identify and interpret the clusters in the visual representation.

Lastly, to facilitate the qualitative analysis of each cluster, the most frequently occurring keywords in each cluster were ranked. Using the graphical network mapping of keywords and the ranking of keywords in each cluster, a theme was assigned to each cluster.

4. Discussion

This study maps the scientific landscape of the literature on aging in place through a bibliometric analysis. The results highlight the multifaceted nature of aging in place, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach to understanding and addressing the diverse factors influencing successful aging in place. The study identifies key research areas, leading countries, institutions, and journals, central publications, and the temporal evolution of themes in the literature. These findings offer valuable insights into the current state of research and suggest several critical considerations for future work.

In our network analysis of the research on aging in place, we identify five major research-area clusters, each characterized by prevailing keywords and their interconnections. We label these clusters based on their dominant keywords as follows: (1) aging-in-place facilitators, (2) age-friendly communities, (3) housing, (4) assistive technologies, and (5) mental health.

As individuals age, their ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) independently can decline [

41] due to physical [

42] and cognitive limitations [

43]. This makes caregiving an important factor in aging in place, which is also evident in

Figure 1, as it is central to the aging-in-place facilitators cluster (cluster 1). For instance, Vreugdenhil [

44] identified dementia, caregiving, and informal care as critical concerns related to aging. Caregiving can range from formal arrangements, like long-term care facilities to informal support through home care e.g., [

45].

Both caregiving and the home environment impact successful aging in place [

19]. To that end, creating a barrier-free environment is essential, making home modifications a critical strategy to ensure universal design [

46]—an idea that connects the aging-in-place facilitators cluster to the housing cluster. Evidence shows that such home modifications can lead to longer stays in one’s home, thereby supporting aging in place [

13].

Technology is another important facilitator, enabling tools like telehealth [

47]. As shown in

Figure 1, keywords such as

telehealth and

telecare connect the aging-in-place facilitators and assistive technologies clusters, emphasizing the role of technology in supporting independent living and providing care [

48]. Technologies can help with early illness detection [

49], fall and emergency detection through sensors [

50], and assistance from robots [

51]. However, several factors, such as age, education level, and whether individuals live alone, can influence the acceptance of technology by older adults, as highlighted by Chimento-Diaz et al. [

52].

Formal care is also essential in supporting older adults, with long-term care emerging as a key concept in the mental health cluster. Studies indicate that long-term care facilities can lead to negative outcomes, including loneliness [

53], social isolation [

54], and depression [

55]. On the other hand, Bolton and Dacombe [

4] investigated how social isolation can impact health among older adults who are aging in place. Their study emphasized that aging in place can increase the risk of social isolation, which may in turn lead to various health problems.

The keywords

mental health and

health promotions bridge the housing and mental health clusters. This connection is logical, as promoting aging in place—allowing elderly individuals to remain in their homes rather than transitioning to long-term care facilities—can have a positive impact on their health [

56]. Studies show that elderly individuals prefer to remain in their homes [

8], where they feel a sense of belonging and attachment. For example, Muszyński [

57] examined various aspects of housing and found that the home environment reflects multiple dimensions of an older person’s identity, including physical, biographical, aesthetic, and axiological dimensions. The study highlighted two key aspects of place: (1) objects collected by older adults and (2) activities in which they engage in their homes.

The housing cluster connects with the assistive technologies cluster via keywords like

smart homes e.g., [

58]. However, they appear distantly related in

Figure 1, indicating limited overlap between these research areas.

Cluster 2, titled age-friendly communities, is closest to the housing cluster since both pertain to built environments at different scales. This suggests that age-friendly environments require planning at various levels, from urban [

59] to home scales [

60], to create a supportive fit between individuals and their environments [

39]. The place attachment theory can explain the positive effects of such environments [

12,

61]. Lewis and Buffel [

39] explored how place attachment and the sense of belonging in neighborhoods evolve over time for individuals who are aging in place. The study found that these feelings can vary widely among people based on their personal circumstances and changes in their community.

4.1. Limitations

This study has three major limitations. First, it relies solely on the Web of Science database. While comprehensive, the Web of Science may not include all relevant studies, and our review may thus have left some out of the analysis. For example, PubMed is frequently used in medical fields, and excluding it could lead to omitting relevant studies. However, because this study encompasses 3240 records, and most high-quality literature in PubMed is also indexed in the Web of Science, it is reasonable to assume that the study provides representative coverage of the main topics.

Second, it is possible that some irrelevant studies were included among the identified publications. However, the use of co-occurrence analysis, which assesses the relevance of studies based on the co-occurrence of keywords in the same document, mitigates this problem. Because keywords unrelated to aging in place are less likely to appear with relevant keywords, co-occurrence analysis reduces the inclusion of irrelevant studies.

Third, bibliometric analysis does not reveal the direction of relationships or indicate causal connections between nodes. Therefore, it should be used as a complementary method alongside a traditional literature review [

24].

4.2. Conclusions

This study provides an overview of the landscape of the literature on aging in place, identifying key research areas, influential publications, and evolving trends. The findings highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary and holistic approach to supporting aging in place that encompasses its physical, cognitive, social, and technological dimensions as well as the built environment in which aging in place occurs. By leveraging the insights enabled by this study’s scientific map, future multidisciplinary research can contribute to the development of holistic and effective strategies that allow older adults to age in place with dignity and a high quality of life.