Abstract

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurological disorder typically beginning in middle or late life, with risk increasing with age. Accessing health services for people living with Parkinson’s disease can be challenging and stressful, often resulting in the worsening of current symptoms, the development of new symptoms, including infection, fatigue, and confusion, or medication changes. This can lead to an increased length of stay in hospital and/or readmission, further worsening symptoms. The aim of this scoping review is to explore how quality improvement and healthcare redesign initiatives have contributed to understanding issues around length of stay and readmission to hospital for people living with Parkinson’s disease. The review was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s framework and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist. The Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), Medline, and Cumulated Index in Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) databases were searched for relevant articles published between 2019 and 2023. The included articles were categorised using thematic analysis. Ten articles were included in this review, resulting in the following three major categories: issues contributing to length of stay and readmission, interventions, and recommendations. Quality improvement and healthcare redesign can improve the length of stay and readmission rates for people living with Parkinson’s disease through robust design, delivery, and evaluation.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurological disorder affecting approximately 8.5 million people globally [1] and is characterised by a range of motor and non-motor symptoms. These include tremor, rigidity, postural instability, bradykinesia, autonomic dysfunction, mood disturbances, cognitive impairment, sleep disorders, and pain [2]. These symptoms progress over time, with a recent post-mortem analysis suggesting that people typically live 6.9 years to 14.3 years after a diagnosis [3]. Although the progression of the disease is variable between individuals and highly heterogenic, the resultant increasing disability has been shown to lead to higher hospital admission rates [1,2]. Recent studies have identified four main reasons for hospitalisation among people with PD. These include infections, such as urinary tract infections and pneumonia, worsening motor features contributing to reduced mobility, falls and fractures, delirium, dementia, and associated neuropsychiatric symptoms and autonomic features of PD including gastrointestinal complications, orthostatic hypotension-related syncope, and adverse drug events [2,3,4].

Health services for people living with PD generally involve an integrated care coordination model, due to the complexity of the symptomatology. Integrated care, defined as a care approach designed according to the multidisciplinary needs of the patient, has been shown to improve patient-reported health-related quality of life compared with standard care [5]. Integrated models of care for PD patients typically include healthcare providers working across settings and levels of care. Medical and surgical management and consultations, allied healthcare, and rehabilitation are common for PD patients in both the inpatient and outpatient settings [5]. Integrative models for chronic conditions have been demonstrated to reduce hospital admissions, decrease length of stay, and reduce costs, and are more effective when targeting single conditions and providing care in patients’ homes [6]. Despite this patient-centred multidisciplinary model of care, challenges remain for health services around PD patient admissions and the length of stay in hospital.

Length of stay in hospital is influenced by a range of factors related to PD. Previous studies have reported on complications post-operatively for PD patients including increased costs, mortality, length of stay following total hip arthroplasty [7], increased adverse events such as aspiration pneumonia and urinary tract infection following non-neurologic surgery [8], and the deterioration of respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurologic function due to general anaesthesia [9]. People living with PD who are admitted to hospital with a PD-related cause have been shown to have a significantly longer length of stay than those who do not have a PD-related cause for admission [10,11,12,13]. Gil Prieto (2016) demonstrated that 87% of PD patients had at least one co-morbidity, with the most frequent causes for hospitalisation being respiratory infection, urinary tract infections, cardiovascular disease, and falls and fractures. Hospitalisation rates for PD patients increase with age [13], with emergency PD admissions being the most common cause of hospital admission [12]. Gerlach [14] found that PD patients often left hospital with worse motor function, with medication errors being the most important significantly related risk factors for deterioration, followed by infections during hospitalisation. Therefore, reducing the length of stay of PD patients is one mechanism for the improvement in quality of the overall patient experience and outcomes for people living with PD.

The purpose of this scoping review is to identify whether healthcare redesign and quality improvement projects contribute to improving the PD patient length of stay and (re)admission to hospital. This includes reason(s) for admissions, patient experience in hospital, and quality improvement interventions that have been utilised to reduce length for stay for PD patients. The authors are not aware of any systematic reviews or meta-analyses that focus on redesign work undertaken to improve the management of PD patients in hospital, to date.

2. Materials and Methods

The scoping review was guided by the Arksey and O’Malley [15] six-stage framework, without the optional consultation stage, and was reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Met-Analyses (PRISMA) framework [16]. We did not register this protocol.

2.1. Stage 1: Identifying the Research Questions

This scoping review assessed the following research questions:

- What issues have been identified that contribute to readmission for PD patients and PD patients having a longer than average length of stay (LOS) compared to the overall hospital average LOS?

- What solutions and interventions have been identified and evaluated to reduce LOS and readmission for PD patients?

2.2. Stage 2: Search Strategy

A search of the literature was conducted in August 2023 using three databases: EMBASE, Medline, and CINHAL. Search terms were informed by previous published literature and categorised into four silos using a Population, Intervention, Context, Outcome (PICO) format [17] (Table 1). The MeSH thesaurus was used for CINAHL and Medline, and the Emtree thesaurus was used for Embase to ensure we captured terms reflecting the aim of our review. The Boolean operator “OR” was used within each silo and “AND” was used to join the silos. Each silo reflects an aspect of the research question. The timeframe for our search was 2019 to 2023, reflecting the period of increasing quality improvement publications in acute health services, relevant to current service delivery.

Table 1.

Search terms according to PICO criteria.

2.3. Stage 3: Screening and Study Selection

After the automatic and manual removal of duplicates (n = 15), titles and abstracts were manually screened by the lead author based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). The full texts of studies that met the inclusion criteria were screened independently by two reviewers and any conflicts were discussed and resolved.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.4. Stage 4: Data Extraction

The data were extracted according to the project design or process, the aim or problem statement, participant description, setting, and outcomes or goals of each project. Next, information from each report was collected according to the descriptions of the issues their project identified as contributing to LOS and (re)admissions, the solutions or interventions implemented to address the issues, and project evaluation detailing results and benefits. Finally, the steps each project took to adjust their interventions or overcome unexpected barriers to further improve their initial results, and the recommendations outlined for others seeking to perform similar work were listed (Appendix A).

2.5. Stage 5: Data Collation, Summary, and Reporting

The data were analysed and summarised according to themes consistent with the methodology for scoping reviews [18]. The thematic analysis was conducted using a six-step process: familiarisation, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining, and naming themes, and writing up [19].

3. Results

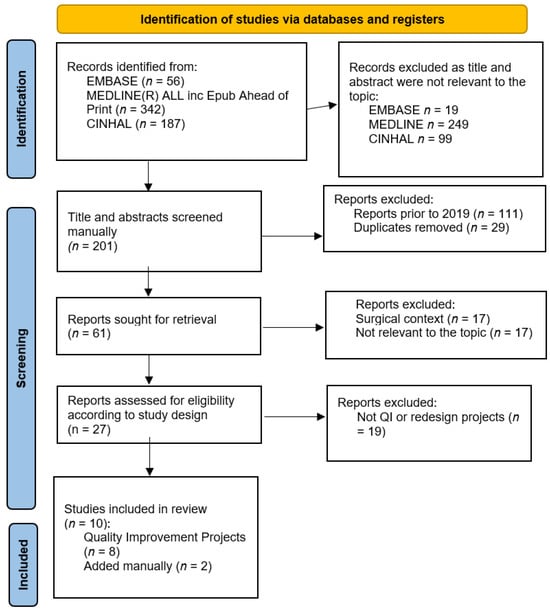

This scoping review yielded eight articles. Two reports known to the author were added manually, one from a non-indexed journal and one from a previous project. A final ten articles were included in the review. This is represented visually in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1). A summary of the literature is provided below, and three themes related to the research questions are discussed.

Figure 1.

PRISMA chart.

3.1. Summary of the Literature

Four reports described their work as a redesign or quality improvement project, noting a redesign methodology or framework [20,21,22]. One did not include the framework description [23]. Two reports were retrospective observational evaluations of one of the redesign projects [24,25]. Four reports were retrospective observational studies, audits, or evaluations conducted before and after a described set of interventions [26,27,28,29].

The participants in all reports were people with Parkinson’s disease admitted to acute care hospitals. The identification of participants referred to ICD 10 coding in three cases [20,24,26]; six studies did not provide criteria for the identification of their PD patient cohort [21,22,23,25,29]; three specifically required evidence of PD diagnosis by a specialist [26,27,28]. Three reports described staff as both targets of and participants in the redesign process [21,22,23]. Hospital settings ranged from large tertiary or teaching hospitals [20,22,24,26,28] to smaller regional hospitals without a specialty unit [21,25,27,29]; one report combined resources of a centre of excellence with a regional hospital [23].

All reports aimed to improve services to enhance the patient’s experience. Eight reports listed improved patient journey or experience as a primary goal or outcome, implementing a change in service that involved a new specialist service team or nurse [20,21,22,25,26,28,29]. Seven reports had goals and outcome measures related to medication management, including accurate prescribing, a reduction in medication errors and the avoidance of contraindicated medications [20,21,24,27,29], and the timely administration of medications [21,22,23,29]. Seven reports had goals and outcome measures specific to LOS and (re)admissions [22,24,25,26,27,28,29].

3.2. Theme 1: Issues Contributing to LOS and (Re)Admissions

The severity and complexity of PD symptoms were identified as impacting LOS and (re)admission [24,26,28], particularly with reference to falls and pneumonia [21,23,24,26], poor medication management [20,21,27], and neuropsychiatry and postural hypotension [26]. Due to the complexity of the disease, the reasons for admission varied and often led to admissions across the hospital to various services, contributing to a lack of focused specialised care during admission [20,21,22,24] or gaps in services [28]. A first admission to hospital is an indicator for future admissions [23,26]. Other reasons for admission to hospital included sepsis or other infections, urinary tract infections [24,26], and cardiac, renal, or orthopaedic reasons [24].

3.3. Theme 2: Interventions

Interventions targeted patient identification, specialised care plans or pathways, staff education, and medication management and swallow [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] to reduce length of stay and readmission. The identification of patients within the hospital system used electronic medication record (EMR) systems or electronically generated reports [20,21,29]. These alerts or reports notified specialised care teams or a PD nurse of the arrival of the PD patient to enable timely assessment, the provision of specialised advice, and recommendations for treatment or discharge [20,25,26,28,29]. In one case, the identification of PD patients led to the prospective collection of patient demographic data [26]. Specialised care plans or pathways [20,22] were initiated in an early and timely fashion [25]. These consisted of specialised PD team meetings [24], PD nurse review and interventions [25,29], or posters providing information of key contacts available for medication advice [22].

Multifaceted staff education programmes were implemented across hospitals [24,25]. Education programmes consisted of posters and or stickers [20,21,22,23,30], reminding staff of the time-critical nature of PD medications. These materials complemented regular education sessions focusing on the complex nature of PD symptoms and the medication regimes [20,22,27,29]. In some instances, electronic modules, including videos, were developed to enable the repetitive presentation of material in a time-efficient way [20,22].

Other strategies to improve medication management included timely reviews of medication charts by a pharmacist [20,23,27] or specialist team [26,29]. Medication formularies were reviewed to ensure medications were available, reducing the time until the administration of the first dose of PD medication [20,21,23]. EMR upgrades included prompts and reminders for prescribers and nurses [22,23] or small alarm clocks for nurses to carry to prompt them to administer medication on time [22]. Projects that identified poor patient swallow as a priority developed an algorithm to switch from oral medication if swallow is compromised [21] or implemented an ‘urgent’ pathway for the insertion of nasogastric tubes in radiology for PD patients [22] to minimise disruption to symptom control when swallow was compromised. Reports that followed a robust redesign methodology also included descriptions of gathering a multidisciplinary team of staff to contribute to the redesign process [20,21]. Others emphasised the role of the consumer and the patient’s story to ensure interventions would be effective in addressing patient needs [21,22,28].

Ongoing monitoring of performance indicators was a specific strategy for continued improvement [24]. The evaluation of interventions demonstrated that the identification of patients improved [21,27], medication incidents reduced [21,24,27,29], and pharmacy reviews were conducted in a timely fashion [27]. There were improvements in medication administration workflow [23] and timely administration [21,22,23,24,27,29], with some outcomes including increased self-medication [22,29].

LOS was reported to have reduced by between 8 and 50% [21,24,25,27,28,29] with cost savings of up to AUD 8600 per person per year in Australia [25]. Very little was reported on changes to readmission rates, with one study reporting no change [27]. However, improvements in patient and carer experience [21,22,23,28] and improved staff satisfaction [21,28] were widely reported. Common outcomes included improved service delivery [21,22,28], access to specialised services [26], timely interventions and discharge advice [26], reduced complication rates, and a reduced need to increase care after discharge [27]. Services gained a better understanding of their PD patient cohort [26] and reasons for readmissions [28]. Patients admitted from aged care facilities had longer LOS [26]. Improvements extended beyond the wards, enabling interventions across the hospital [23] and assembling stakeholders with a common goal—to bridge departmental and professional barriers [20,29].

3.4. Theme 3: Recommendations

All studies made recommendations for their service or for others considering similar projects. Recommendations included developing electronic reporting to identify patients and measuring outcomes to allow ongoing data review for enduring benefits [20,21,25,29]. Following up these reports with stakeholders such as hospital executive or nurse managers provides the opportunity to develop further actions to address underperforming measures, non-compliance, and patient and carer complaints [20,21,22,29] until changes become core business [21]. This type of ongoing evaluation process as part of a performance improvement structure or healthcare redesign framework also includes a coordinating committee [20,21], where focus on the consumer’s story and consultation further improves outcomes [22].

Three reports recommend collecting demographic data and occasions of service in a prospective manner/on arrival at the hospital [24,25,27]; one recommends pharmacy or clinic records as a means of doing so [26]. A large cohort is recommended to reach statistical significance, as a larger sample size and longer period of intervention would better indicate resources are well-spent [27,28]. PD is complex, and the impact of orthostatic hypotension, delirium, and dehydration should also be considered [29]. To address this complexity, an ongoing collaborative multidisciplinary team approach to solving problems of patient care that includes occupational therapists and physiotherapists [29], as well as bedside nurses and pharmacy [20,21,22,29]. An on-call service after hours would also be beneficial [29].

Ongoing education [20,22,27] for hospital staff and PD specialists [29] is required to accommodate staff turnover [27]. A formalised clinical guideline or model of care and interventions that are simple and easy to use [21,22,27] means that results are replicable in different settings within the hospital or to other services/hospitals [22,24,25].

Overall, we recommend building on previous redesign work, learning from their lessons and recommendations to avoid reinventing the wheel, so that future redesign projects implement changes to practise that are already known to be effective, cost-efficient, and improve patient outcomes, with the added benefit of further improving on these previous interventions. This means a greater likelihood of effective, sustainable, and meaningful improvements.

3.5. Limitations

The limitations of this scoping review include the small number of published quality improvement and redesign initiative papers that were found. The authors acknowledge that many quality improvement and redesign projects are not published, but still contain valuable, local information pertinent to improving health services for people with Parkinson’s disease. The authors did not quantify variables, such as severity, which contribute to changes in LOS; rather, we broadly scoped the current literature around the outcomes and impact of variables. The dates selected for our search may have further limited the fundings; however, we feel it is important to capture improvement data relevant to current systems and processes within Parkinson’s disease health service delivery. A broader search may yield a higher number of results but may not be relevant to current health services. Further, a quality assessment of the included studies was not performed. This is not a requirement of scoping reviews and may result in some included studies being of poor quality.

4. Conclusions

An increased length of stay is a major contributor to poor experiences and outcomes for patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Robust quality improvement and redesign interventions are effective in improving the hospital admission experience of PD patients. However, ongoing review post-implementation is required to sustain improvements in the long term. Improvements to hospital services that address inefficiencies and workflow can reduce LOS and reasons for admissions can be better understood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.; methodology, S.W. and S.J.P.; formal analysis, S.W. and S.J.P.; investigation, S.W. and S.J.P.; data curation, S.W. and S.J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W. and S.J.P.; writing—review and editing, S.W. and S.J.P.; supervision, S.J.P. project administration, S.W. and S.J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Data Extraction Table.

Table A1.

Data Extraction Table.

| Study Year Design/Process | Aim/Problem Statement | Identification of Participants | Setting | Outcomes/Goals | Issues Contributing to LOS and (Re)Admission | Solutions/Interventions | Findings/Results Benefits/Effectiveness | Recommended Next Steps for Their Project | Lessons or Recommendations for Other Teams? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azmi et al. 2019 [20] Quality improvement project/ followed clinical redesign model/ plan–do–study–act. | “To formalize efforts to improve the care of patients with PD admitted to hospital by using the DSC certification pathways as an established route for tacking selected quality measures with continues assessments of the program”. | Any patient with a primary or non-primary diagnosis of PD admitted to the hospital (ICD10 G20 code). | Hospitalised inpatients with PD in Hackensack, NJ, USA; large tertiary referral centre with multidisciplinary team of stakeholders. | - Accurate medication prescribing; - Avoidance of contraindicated medications; - Early mobility after deep brain stimulation surgery; - Patient and family satisfaction with medication management; - Development of protocol to provide framework of best practise, equips bedside nurses. | - 85% enter the hospital for non-PD-related conditions; - Admissions span departments and units; - Medication errors; - Contraindicated medications; - Delayed administration; - Difficulty prescribing custom orders; - Unavailability of PD medications on formularies. | - Defined problem, assembled multidisciplinary team; - Team caring for the patient is alerted to PD diagnosis and care plan is triggered regardless of reason for admission; - Identification of PD patients within the hospital by daily Information Technology report; - Review medication charts; - Parkinson’s care plan; - Education and staff awareness posters and modules (ongoing); - Stakeholder engagement—executive level to frontline staff, and multidisciplinary involvement; - Pharmacy review of medication charts to detect and correct errors; - Including most PD medications on formulary. | - Certification of PD care pathway; - Assembled stakeholders with common goal; - Data metrics were developed to track performance; showed improvement over 1 year in all areas but were not included in the article (detailed results in Azmi 2020). | Monthly review of data with stakeholders to develop actions for unperforming measures. Care team informed of variances so that follow-up emails and further meetings can be arranged. Ongoing reporting to hospital executive. Ongoing education for patients and staff. | Provide guidance to other hospital systems interested in the patient population. Importance of IT support to develop a report for the PD team. Identifying where the PD patients can be found within the hospital each day. Importance of a performance improvement structure that also includes a coordinating committee. Role of the pharmacy as part of the team and in the interventions. The importance of the bedside nurse in achieving these improved outcomes. |

| Azmi et al. 2020 [24] Evaluation of redesign project; retrospective observational cross-sectional study. | “Assess effects of a hospital-wide initiative on proper PD medication orders, avoidance of contraindicated medications and the resulting effects on LOS in the 24 months following implementation”. | All patients admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of PD, with PD included in EHR ‘problem list’ regardless of their admitting diagnosis. (ICD10 code G20); 569 pts 2 yrs; excluded = did not have PD entered in their problem list. | Hospitalised inpatients with PD in Hackensack, NJ, USA; large tertiary referral centre with multidisciplinary team of stakeholders. | - PD medications are ordered in a custom fashion; - Contraindicated medications were not administered; - Charts reviewed on a daily basis to identify errors or omissions and rectify them. | Reason for admissions list: sepsis or other infection, PD, pneumonia, cardiac, renal, orthopaedic, respiratory failure; admitted throughout the hospital according to reason for admission/primary diagnosis. | - Implementation of hospital-wide medication management protocol supported by multifaceted continuing education programme (details listed in Amzi et al. 2020); - PD team meetings to review data and implement actions for ongoing improvement. | - Threefold increase in customised prescribing of PD medications; - Majority of orders still placed without custom timing, but increase in the number of corrections of custom timings; - Most orders for contraindicated medications were NOT administered; - LOS improved from 7.1 days to 6.7 days (8% decrease). | Ongoing work to improve the number of orders with custom timings. | - Joinr Commission program fo Disease Specific Certification (JC-DSC) platform as a vehicle to identify monitor and address the care of a specific patient population; - To extend focus to include assessing the timing delays in administration of medications; - Replicated studies in different settings and in a prospective manner. |

| Bramble et al. 2021 [25] Retrospective comparison of hospital LOS and readmissions; cost benefit analysis of services; evaluation and cost–benefit analysis of PD nurse role. | “Aim to examine the cost-effectiveness of employing specialist Parkinson’s nurses in a regional community in Australia.” | All patients with PD admitted to Coffs Harbour Base Hospital between control period of 1/1/13–31/12/14 and intervention period of 1/1/16–31/12/17. ICD-10 code not specified. | Hospitalised patients a regional Hospital Coffs Harbour Australia | - LOS; - No. of services provided by the PD nurse; - No. of services provided by other health professionals; - Patient readmissions; - Cost–benefit analysis of PD nurse position. | None documented | - Employment of PD nurse specialist; - Nurse-led quality improvement project (detailed in Carroll 2020 (11)); - Early and timely care delivered in both the acute and community/residential aged care to prevent infections, symptom deterioration, and deterioration in mental health. | - Impact of PD nurse results in a decreased LOS ranging from 0.37 days (AUD 1924) to 0.77 days (AUD 3926); - Cost savings of AUD 8600 per person over 3-year period; - Cost savings outweigh the cost of employing the PD nurse. | - Findings are informing the design of four Department of Health-funded 3-year pilot projects of specialist movement disorder nurse-led services across rural Australia; - Results will contribute to the creation of similar nurse-led models in regional and rural Australia. | - Importance and cost benefits of accessing a specialist PD nurse to the acute sector; - A prospective study where occasions of service by the PD nurse are captured over a period of time in primary health and community settings to illustrate how their cases of care may also be reduced. |

| Carroll et al. 2020 [21] Clinical redesign project; - Followed clinical practise improvement methodology; - Plan–do–study–act audit and feedback cycles; - Qualitative—focus groups and free text in surveys—and quantitative—surveys, chart audits, and hospital data. | “Streamline hospital admissions by resolving identified problems. Identify individuals with PD within 4 h of presentation. Essential medication available in the Emergency department. Medications administered on time”. | - Project survey participation:member of support group with a diagnosis of PD or their carer, staff working in that ward (not defined), and PD patients/carers admitted to hospital with LOS >1 day. | Hospitalised patients in regional hospital, Coffs Harbour, Australia. | - Patient and carer satisfaction with medication management; - Reduced adverse events/incidents; - Identification of individuals with PD on presentation to hospital; - Medication safety. Unintended outcomes: 1. Time-critical prompts built into a new electronic medication management system and rolled out across six local health districts. 2. Establishment of a second PD nurse position including required competencies. 3. Development of a state-wide multimedia education module. | - Adverse events (e.g., aspiration pneumonia, falls, contraindicated medications given); - Overall poor patient experience of being in hospital with emphasis on medication management. | - Multidisciplinary clinical practise improvement team supported by hospital exec; - Consumer engagement; - Education materials, sessions, grand rounds, included patient’s story; - Patient identification using EMR on Emergency Department tracking board and automated referral to PD nurse and pharmacist; - PD medications made available in ED to enable timely administration of PD medications in ED; - Bedside pictorial alarm clock signs to indicate time-critical medications; - Time-critical stickers for medication charts; - Clinical algorithm to switch oral medication regimes when patient swallow compromised. | - Consumers and staff reported improved satisfaction with service delivery; - PD patients identified 100% of the time; - Medication incidents reduced; - Improved service delivery; - Time-critical prompts now incorporated into EMR; - Reduced LOS from 8.97 days to 6.22 days. | Formal and informal monitoring of guideline compliance to ensure sustainability. Team meetings to discuss non-compliance and patient and carer complaints. Changes became core business. | Benefits of collaborative team approach to solving issues for people with PD presenting and admitting to hospital. Provision of replicable model of care and formalised clinical guidelines to standardise care in the study setting. |

| Corrado et al. 2020 [22] Institute for Healthcare Improvement Model for Improvement Quality Improvement methodology and Breakthrough Series collaborative methodology. | “Primary aim: To improve quality of care for inpatients within 6 months through timely medication administration. Secondary Aims: 1. reducing transfers of PD patients to neurology specialty care for rescue care 2. Empower patients to self-medicate within the hospital when possible” | - PD patients—not specified how they were identified; - Multidisciplinary group: neurologists, geriatricians, specialist nurses, junior doctors, pharmacists with QI expertise, informatics team, speech and language therapists, physiotherapists. | - Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust; - Emergency departments, pre-assessment, surgical and medical admission units. | - Outcome measure: percentage of medications given with 30 min of time due; - Process measure: time first dose of medication after admission was scheduled and time this was administered, medication omissions; - Balance measures: readmissions to hospital and length of stay. | Lack of holistic care contributes to high readmission rate. Exploring all aspects of care results in a successful discharge. | - Consumer presentation of patient experience; - Bedside posters and magnet alerts for ‘time-critical medications’; - Small alarm clocks for nurses to carry; - Posters summarising key contacts for medication advice; - Biannual ‘masterclass’ for hospital and community staff; - Adapting electronic prescribing system to include option to prescribe medication as ‘time-critical’, i.e., must be given within 30 min; - Updating hospital guidelines on PD care; - ‘Urgent’ pathway for insertion of nasogastric tubes in radiology for PD medications; - ‘Get it on time’ stickers for the ED department; - Staff workshop for self-medication strategies for PD patients; - Educational video highlighting project with Parkinsons UK. | - Mean delay in first dose administration dropped from over 7 h to under 1 h; - Mean percentage of omitted doses of PD medications reduced from 15.1% to 0.6%; - Mean percentage of PD medications administered within 30 min of prescribed time increased from 56% to 78.3%; - Transfers to neurology ward for rescue care increased from one to four per week to two in 4 years; - Reduction in readmission rates; - More patients opting to self-medicate; - Improved patient and carer experience. | Ongoing education of staff through biannual masterclass and ‘learning bursts’ refreshers. | - Project spread to other hospitals within the UK; - Keep the interventions simple and easy to use; - Collaboration with patients, carers, multidisciplinary staff, and consumer organisations to achieve a ripple effect across the organisation and to other organisations; - Consumer story was powerful motivator for staff. |

| Hobson et al. 2019 [26] Retrospective observational study pre- and post-intervention. | “Describe the method, introduction and economic costs of introducing an automated email alert system for a Parkinson’s specialist team for people with PD attending ED. Describe the cause and cost of the unplanned ED attendance, specialist team intervention, LOS and frequency of readmission, patient discharge destination and crude mortality rate”. | - Patients with diagnosis of probable PD from in a specialist team database, and ICD-10 codes G20/21; - NHS Wales; - PD team: consultant, PD nurse specialist, and clinical specialist. | Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, NHS Wales UK. | - Demographic breakdown of PD patients admitted to the hospital; - Within 24 h of receiving e-alert, PD team were able to offer specialist advice by phone, email or direct contact with clinical teams caring for patients. | - Reasons for unscheduled ED admissions: 1. falls +/− fracture; 2. Motor and non-motor symptoms including medication problems, falls, neuropsyciatric problems, UTIs and chest infections. - Mean LOS = 6.8 days, admitted from ED = 11 days; - 33% had unplanned readmission; - 28% had multiple unplanned ED admissions with 4–12-day LOS. | - e-alert system automatically generated emails sent to PD team when patient is clerked on attendance to ED; - Demographic data collected included duration of disease, disease severity (HY), cognitive status, time and reason for admission, LOS, discharge destination, unscheduled readmission within 28 days, and PD team intervention outcomes; - Contact with specialist team included phone or email advice to ED team They review medications to ensure regimen is correct, address contraindicated medication, update current medications and disease symptomatology, advice re: medication adjustments, postural hypotension, neuropsychological and psychiatric assessment, safe swallowing assessment. | - Details of how many patients received what intervention from the PD team; - Falls with injury—more likely to have cognitive impairment, be readmissions within 28 days, or come from an aged facility with a longer LOS; - Timely interventions and discharge planning advice. | Database requires monthly manual check. | - e-alert system is easy and cost-effective to implement using locally based systems; - Biggest difficulty is identifying PD patients; - Electronic pharmacy records or clinic records may assist in patient identification; - ICD-10 coding has a clear demarcation of who responds to email alert. |

| Lance et al. 2021 [27] Retrospective; audit pre- and post-intervention. | “To determine effectiveness of a multimodal education and awareness campaign in reducing medication errors in patients with Parkinsonism at Hutt Hospital”. | - Diagnosis code of PD, Parkinsonism, atypical Parkinsonism, Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) < Lewy, body dementia, or corticobasal syndrome. | Secondary level care hospital, non-PD-specialised service, Hutt Hospital, New Zealand. | - Rate of medication error with a target of zero medication errors; - Secondary outcomes: complications, hospital-acquired infection, delirium, inpatient fall, or venous thromboembolism; - Level of care on discharge; - Readmissions within 3 months; - Death within 3 months. | - Improvements in medication management but no statistically significant improvements in secondary outcomes or LOS. | - Two 30 min education sessions followed by discussion—PD overview and medications; - Sticker alert system for medication charts; - Increased priority for pharmacist review of medication charts. | - Medication error rate of 22.5% reduced to 9.3%; - Medication administration of 0–115 min improved to 4–30 min; - Correct prescribing rate of 63% improved to 95%; - Contraindicated medications prescribed—33% improved to 5%; - Pharmacist review of 52% improved to 62%; - Sticker alert system rate of 0% to 57%; - Complication rate of 45% improved to 38%; - LOS reduced from 13.4 days to 7.7 days; - Reduced need to increase care on discharge after intervention; - In-hospital complication rate of 45% improved to 38%; - No change to readmissions | Must accommodate high turnover of staff to sustain improvements in the future. Pharmacy staff time was limited and an ongoing resource issue. Plan to implement an electronic alert to identify PD patients when they arrive at the hospital. Not sure if there was a reporting bias of hospital complications due to the interventions. | Interventions are easily reproducible. Education was the most important aspect and needs to be ongoing in standard orientation and teaching schedules. Sticker system is easily reproducible but requires annual education to ensure ongoing uptake. A large cohort is needed to reach statistical significance. |

| Lovegrove and Marsden 2020 [28] Service evaluation pre- and post-implementation of a PD pathway. | “Aim of the pathway was to bridge transition from acute care back to the home setting Summarise the service evaluation assessing the effects of the new pathway on routine clinical outcome measures, functional ability and admission related parameters”. | - Inpatients on the ward; - Able to transfer with one person; - No new respiratory conditions or cognitive changes; - A diagnosis of PD according to a neurologist or geriatrician. | Five individuals in the standard group and five in the intervention group, Royal Devon Exeter UK. | Functional ability according to Hoehn and Yahr scale (HYS), modified Barthel index score (MBIS) and Lindop Parkinson’s Mobility Scale (LPMS). Admission-related parameters | - Gap in service provision in transitioning the patients back to home; - Severity and complexity of PD. | - Hospital patient feedback cards; - Both groups received, within 48 h of admission, ward-based therapy and discharge planning, joint assessment by physiotherapist and occupational therapist, subsequent daily therapy for 45 min, mobility, transfers, practise activities for daily living, and photos of the home living environment to help replicate the home environment. - Intervention group: taken on home visits with one or two home therapy sessions; if known to a community rehab home-based team, they were invited to attend the home visit. Inpatient goals were set with the family and patient and early referrals made to community therapy services. Staggered discharges of one night at home prior to final discharge. | - Mean average LOS for intervention group 7.2 days—15.2 days for standard group; - Two patients from each group were readmitted within 14 days for new medical reasons; - No difference on the MBIS; - LPMS 39.4% higher in intervention group; - Feedback card: patients liked home visits and the pathway met their needs; staff felt is was logical and straightforward to implement. | - More home-based therapy sessions may have reduced LOS; - Pathway was resource-heavy but felt the benefits outweighed the greater use of resources; - Small sample size-limits the conclusions, recommend a larger trial to provide a more accurate estimate of effect with a sample size of 178 patients needed. | - Modified Barthel Index not sensitive enough to detect change. - Future trials should seek an alternative occupational therapy specific assessment deemed suitable for PD that reflects their goals. - LOS is an important driver for QI in services and may support similar pathway developments. - The need for increased resources is an important consideration when upscaling and implementing such a pathway. - Randomisation of the groups and assessor blindness would minimise bias for disease severity. - Larger sample size over a longer period of time would add robustness to the study. |

| Moore et al. 2022 [29] Retrospective observational Audit pre and post intervention. | “Reflect on the role of a PD Nurse specialist. To examine the management of People with PD in a district general hospital”. | 31 consecutive PD patient admissions pre- and post-intervention were compared. | District general hospital, Royal Devon University Healthcare Trust. | - Average LOS; - Delays to initial dose of medication; - Any contraindicated medications; - Number of patients assessed to self-medicate; - Improve patient journey when admitted to hospital and in turn reduce LOS. | - Digital system to alert staff when PD patients were admitted to the hospital for early review by specialist team; - A hospital PD nurse to coordinate admissions, provide and overview of medications, and support patients and staff. | - 50% reduction in LOS from 24 days to 12 days to 9 days; - 24% increase in accurate prescriptions; - 20% decrease in contraindicated medications; - Delay in medications prescribed and administered of 60% reduced to 3%; - 34% of patients assessed to self-medicate; - Improved medication management and bridged departmental and professional barriers. | Prompt assessment to ensure effective PD management, alongside the presenting medical or surgical condition. PD nurse role extended from 2 years to permanent due to cost benefits. Secondary effect of empowering other healthcare professionals through set training days and ad hoc support. PD nurse must receive ongoing professional development to remain a safe practitioner. Multidisciplinary (MDT) consultants, registrars, pharmacists, and various therapists. | Would an on-call system benefit patients admitted out of hours? A patient satisfaction questionnaire would provide more in-depth and qualitative data on the patient experience. Develop the MDT including a physio and occupational therapist, as this may alter prescribing practise if alternative strategies are available. | |

| Nance et al. 2020 [23] Quality improvement initiative. | “To improve timely administration of levodopa carbidopa medications in a community hospital affiliated with a centre of excellence, following a series of educational, pharmacy and nursing support interventions implemented as a result of patient complaints”. | PD patients. Details not provided. Physician, nursing, and rehabilitation leaders’ patients and families across facilities, nursing staff, informatics discharge planners, and EMR tech teams. | Struthers Parkinson’s Centre—PF designated as excellent, treating 2000 patients with PD. Park Nicollet Methodist Hospital, 361 bed hospital. Shared electronic medical records (EMR). | Statistically significant improvement in the timeliness of levodopa medications. Administered within 60 min, 30 min, and 15 min of the scheduled time. | Improvements in patient outcomes, e.g., LOS readmission rates, in-hospital complications such as falls, pneumonia, or transfer to higher level of care were not measured. Patients once admitted to the hospital are likely to return. | 15 min time-sensitive alert and instruction reminder created within EMR—later modified to 1 min to remind nurses of the time sensitive nature of the levodopa medication. They do not need acknowledgment by the nurse, to prevent pop-up fatigue. Visual reminder of PD diagnosis and time-critical nature of PD medications in EMR to enhance handover communication. Levodopa products were added to the automated dispensing machines on the three wards with the highest number of PD admissions to minimise delays in accessing newly prescribed medications. Hospital pharmacist receives a daily report of inpatients prescribed levodopa to address inconsistencies and concerns. | Improvement in medication administration workflows. No objective data—but patients and families report less stress and anxiety during their hospitalisation and that the hospital staff understand their unique needs. Administering levodopa medications within 15 min of the scheduled time does not appear burdensome to staff. Proportion of doses given within 15 min (43%), 30 min (66%), and 60 min (90%) pre-interventions. Post-interventions = 71%, 86%, and 96.5%, respectively. Improvements in all nursing units across the hospital even though education and ward stock were only provided to neurology and general medical units. | Additional work needed to 1. determine how/whether successful levodopa administration (a process outcome) relates to successful admission (a patient outcome); 2. understand relationship between timely administration of levodopa and patient sex, time of day, and day of hospital stay. PD in hospital is complex and there are a lot of other aspects of the disease that should be studied: tube and oral feeds interaction with medications; relationship between orthostatic hypotension and illness, immobility, and dehydration; increased risk of delirium; and the need to avoid contraindicated medications. A separate project addressed doses ‘not given’. Improvements have been sustained due to the enduring nature of the EMR alerts. Ongoing data collection and analysis through an EMR report to nurse managers on their unit’s performance. | Improvements have been sustained due to the enduring nature of the EMR alerts. |

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO). 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Sveinbjornsdottir, S. The clinical symptoms of ’Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, A.D.; Taylor, K.S.; Counsell, C.E. Mortality in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Brennan, L.; Bloem, B.R.; Dahodwala, N.; Gardner, J.; Goldman, J.G.; Grimes, D.A.; Iansek, R.; Kovács, N.; McGinley, J.; et al. Integrated Care in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1509–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damery, S.; Flanagan, S.; Combes, G. Does integrated care reduce hospital activity for patients with chronic diseases? An umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2016, 21, e011952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, J.E.; Eltorai, A.E.M.; Rubin, L.E.; Daniels, A.H. Matched cohort analysis of peri-operative outcomes following total knee arthroplasty in patients with and without Parkinson’s disease. Knee 2019, 26, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Chou, Y.C.; Yeh, C.C.; Hu, C.J.; Cherng, Y.G.; Chen, T.L.; Liao, C.C. Outcomes After Non-neurological Surgery in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease: A Nationwide Matched Cohort Study. Medicine 2016, 95, e3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadate, Y.; Nakashige, D.; Omori, K.; Matsukawa, T. Risk factors for postoperative complications in patients with Parkinson disease: A single center retrospective cohort study. Medicine 2023, 102, e33619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunoye, O.; Kojima, G.; Marston, L.; Walters, K.; Schrag, A. Factors associated with hospitalisation among people with Parkinson’s disease—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2020, 71, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommel, A.L.A.J.; Krijthe, J.H.; Darweesh, S.; Bloem, B.R. The association of comorbidity with Parkinson’s disease-related hospitalizations. Parkinsonism. Relat. Disord. 2022, 104, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibdat, N.S.; Ahmad, N.; Azmin, S.; Ibrahim, N.M. Causes, factors, and complications associated with hospital admissions among patients with Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1136858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Prieto, R.; Pascual-Garcia, R.; San-Roman-Montero, J.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Castrodeza-Sanz, J.; Gil-de-Miguel, A. Measuring the Burden of Hospitalization in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease in Spain. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, O.H.; Broen, M.P.; Weber, W.E. Motor outcomes during hospitalization in Parkinson’s disease patients: A prospective study. Parkinsonism. Relat. Disord. 2013, 19, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, P.; Petrisor, B.A.; Farrokhyar, F.; Bhandari, M. Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Can. J. Surg. 2010, 53, 278. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A.; Papaioannou, D.; Sutton, A. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. 2008, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, H.; Cocoziello, L.; Harvey, R.; McGee, M.; Desai, N.; Thomas, J.; Jacob, B.; Rocco, A.; Keating, K.; Thomas, F.P. Development of a Joint Commission Disease-Specific Care Certification Program for Parkinson Disease in an Acute Care Hospital. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2019, 51, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, V.; Deutschmann, K.; Andrews, J. Purposeful collaboration: Enriching lives for people with Parkinson’s disease. Australas. J. Neurosci. 2020, 30, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, J.; Jackson, O.; Baxandall, D.; Robson, J.; Duggan-Carter, P.; Throssell, J.; Westgarth, T.; Chhokar, G.; Alty, J.; Cracknell, A. Get Parkinson’s medications on time: The Leeds QI project. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, M.A.; Boettcher, L.; Edingerm, G.; Gardner, J.; Kitzmann, R.; Erickson, L.O.; Wichmann, R.; Wielinski, C.L. Quality Improvement in Parkinson’s Disease: A Successful Program to Enhance Timely Administration of Levodopa in the Hospital. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 10, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, H.; Cocoziello, L.; Nyirenda, T.; Douglas, C.; Jacob, B.; Thomas, J.; Cricco, D.; Finnerty, G.; Sommer, K.; Rocco, A.; et al. Adherence to a strict medication protocol can reduce length of stay in hospitalized patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Clin. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 3, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramble, M.; Wong, A.; Carroll, V.; Schwebel, D.; Rossiter, R. Using an economic evaluation approach to support specialist nursing services for people with Parkinson’s in a regional community. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4722–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson, P.; Roberts, S.; Davies, G. The introduction of a Parkinson’s disease email alert system to allow for early specialist team review of inpatients. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, S.; Travers, J.; Bourke, D. Reducing medication errors for hospital inpatients with Parkinsonism. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, C.J.; Marsden, J. Service evaluation of an acute Parkinson’s therapy pathway between hospital and home. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2020, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Jackson, S.; Yousuf, A. Medication management for patients with Parkinson’s: The impact of a nurse specialist and non-medical prescribing in the hospital setting. J. Prescr. Pract. 2022, 4, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, H.; Genc, G.; Saad, S.; Thompson, N.; Oravivattanakul, S.; Alsallom, F.; Yu, X.X.; Floden, D.; Gostkowski, M.; Ahmed, A.; et al. Factors Associated With Postoperative Confusion and Prolonged Hospital Stay Following Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery for Parkinson Disease. Neurosurgery 2020, 86, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).