Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurocognitive disorder characterized by gradual onset and gradual progression, presenting a wide range of symptoms, with one of its main features being episodic memory impairment, present from the early stages of the disease. Currently, there is no cure for AD, so a multidimensional approach combining pharmacology with other non-pharmacological treatments is recommended to halt or delay cognitive and functional decline in patients. In this regard, music therapy emerges as a promising non-pharmacological treatment for memory in patients with AD, as musical memory appears to be preserved, retaining the ability to recall familiar songs and the memories associated with them. Therefore, the aim of this study is to conduct a systematic review of the current state of scientific research on the effects of music therapy on the memory of patients with AD in mild and moderate stages. A search was conducted in the Google Scholar, ProQuest, Summon, Web of Science, and Scopus databases, finding 15 articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The results seem to support the use of music-based interventions for memory in patients with AD, especially regarding autobiographical memory. However, given the limitations encountered, we consider that the results pave the way for future research rather than providing solid conclusions about their effectiveness.

1. Music Therapy as Non-Pharmacological Treatment in Alzheimer’s Disease—Effects on Memory—Systematic Review

According to the World Health Organization [1], dementia is one of the leading causes of disability and dependence in old age. In 2019, the number of affected individuals worldwide was 55.2 million (8.1% of women and 5.4% of men over 65 years old), and this number is projected to increase to 78 million by 2030 and approximately 139 million by 2050. The increase in longevity, global population growth, and certain lifestyle-related risk factors (such as alcohol consumption, smoking, a sedentary lifestyle, hypertension, etc.) have made dementia one of the leading causes of death globally, ranking seventh.

Dementia arises from various brain diseases, with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) being the most prevalent, constituting 60% to 70% of cases [2]. The DSM-5 [3] recognizes “major or mild neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease”, noting its gradual onset and progression. A hallmark symptom is declining episodic memory [4], causing challenges in recalling past events and remembering to whom information was disclosed [5].

During the mild stage of the disease, individuals may experience significant memory loss, language difficulties, decision-making problems, disorientation, lack of interest, etc. In the moderate stage, individuals with AD start to lose autonomy in performing daily activities and may have trouble living alone. They may also experience personality and behavioral changes, increased speech difficulties, and memory problems (especially with recent events and people), and may exhibit wandering and hallucinations. The severe stage is characterized by total dependence, severe memory impairments, and more pronounced physical symptoms [6].

According to Baddeley et al. [4], the brain regions affected at the onset of the disease are the medial temporal lobe and hippocampus, leading to initial memory problems. As the disease progresses, it affects the temporal and parietal lobes and other brain regions. Even though the progression varies among patients, leading to differing symptoms and stages of onset, severe episodic memory deficits are consistently present. At present, there is no cure for AD. Treatments, including drugs and other approaches, focus on enhancing cognition, managing the psychological symptoms, and delaying decline, aiming to maintain independence for as long as possible [7].

Pharmacological therapies include two groups of drugs for the symptomatic treatment of AD, both of which are authorized for use: acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, recommended for patients with a mild to moderate diagnosis, or the non-competitive antagonists of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors, particularly memantine, which has shown efficacy in treating moderate to severe AD [8].

According to MSCBS [9], although numerous studies support medication use, there is currently some debate about their benefits, due to their moderate and transient effects on AD symptoms. Therefore, a multidimensional approach, combining these treatments with other non-pharmacological interventions, is necessary to maintain and stimulate cognition, behavior, and functionality in individuals affected by this disease, aiming to preserve their abilities and slow their decline [9,10]).

Non-pharmacological therapies refer to “any non-chemical intervention, theoretically based, focused, and replicable, carried out on the patient or caregiver and potentially capable of obtaining relevant benefits” ([9], p. 43). Their effectiveness in treating AD symptoms is supported by various findings, such as the retention of neuroplasticity in older brains, the learning ability of individuals with mild to moderate AD, and the capacity for creating new synapses and neuronal regeneration [10,11].

Music therapy as a non-pharmacological treatment has seen significant development in recent years. This development is attributed to brain and biomedical research related to music. It has transitioned from being considered a supportive therapy, with effects on patients’ social, psychological, and emotional functions. Now, it is recognized as a key therapeutic modality in cognitive domains. These domains include attention, executive function, language, and memory. Music therapy has proven effective in neurological rehabilitation, as evidenced by several studies [12,13,14].

Bruscia [15] describes music therapy as a structured health-focused process led by a qualified professional, fostering interaction between patient and therapist. Raglio and Oasi [16] expand on this point, discussing music’s therapeutic uses beyond traditional therapy. They outline three approaches: (1) Music therapy interventions involve a therapist selecting music tailored to specific goals, incorporating active (improvisation, singing) and receptive techniques (listening). Goals include reducing psychological symptoms, improving communication, and evoking emotions and memories. (2) Music listening-based interventions involve personalized playlists created by a therapist or experienced personnel to stimulate cognition or reduce stress. Therapeutic benefits arise solely from the music, without direct therapist–patient interaction. (3) General music-based interventions, without a therapist, aim to enhance well-being and stimulate sensory, motor, and cognitive aspects [16]. Bradt et al. [17] indicate that it is important to make a clear distinction between music interventions administered by medical or healthcare professionals (music medicine) and those implemented by trained music therapists (music therapy).

Music acts as an emotion inducer, enhancing the recall of the stimuli associated with it [18]. Salakka et al. [19] found that emotions induced by music are closely related to its ability to evoke autobiographical memories, concluding that emotions serve as a strengthening link between music and autobiographical memories, influencing the encoding and retrieval processes.

In patients with AD, musical memory, which involves the neuronal encoding of musical experiences, appears to be particularly preserved. Jacobsen et al. [20], using functional magnetic resonance imaging, showed that musical memory relies on different task-dependent memory systems, and the brain regions normally involved in long-term known musical memory encoding are the caudal anterior cingulate and ventral premotor areas. Additionally, results from Janata’s study [21] demonstrate that the key brain areas related to processing music-evoked autobiographical memories (MEAM) are the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate. These brain regions appear to be preserved in patients with AD and only become affected in the late stages of the disease, which could explain why individuals with AD, despite severe episodic memory impairments, retain the ability to recall familiar songs and associated memories [20].

The scientific literature seems to recognize the utility of music therapy for addressing symptoms related to memory in patients with AD. In the study conducted by Irish et al. [22], a significant improvement was found in autobiographical recall in AD patients in the background music condition compared to silence. Familiar music allows AD patients to evoke emotions and memories from their past and can be used as an effective cue for retrieving autobiographical memories [23]. Case studies compiled by Rubinstein and Moltrasio [18] show the positive effects of musical interventions on various memory systems. Similarly, Barcia-Salorio [24] reports several studies demonstrating that music therapy improves and maintains cognitive abilities in AD patients, especially when using the music preferred during young adulthood.

Regarding the underlying mechanisms of the positive intervention effects on cognition in patients with AD, Matziorinis and Koelsch [23] highlight the relationship between neuroplasticity and neurogenesis processes and music’s ability to generate emotions that activate the anterior hippocampus formation, potentially leading to a slowdown in atrophy in this hippocampal region and thus beneficial effects on memory. Based on a meta-analysis, Koelsch [25] highlights the activation of the anterior hippocampal formation, arguing that this activation may also stimulate neurogenesis. Complementarily, some authors [26,27] suggest that in patients with AD, such music-evoked neurogenesis may lead to a deceleration of atrophy in the anterior hippocampal formation and, perhaps, to a reversal of hippocampal volume loss, a change that would have beneficial effects on both memory functions and mood. Another mechanism that may underlie the beneficial effects of music is the stimulation of dopamine release, as music has a strong capacity to activate the brain’s reward network, which involves the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway, with dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain projecting to the striatum, specifically the nucleus accumbens. Therefore, the pleasure evoked by music would increase dopamine availability in the ventral striatum [25], and as has been observed, the administration of a dopamine antagonist reduces the pleasant and hedonic experience of music [28]. Another beneficial effect related to dopamine release is the age-related decrease of this neurotransmitter, which is associated with cognitive deficits. In this regard, studies with musicians have shown a link between musical practice and a lower risk of cognitive decline and dementia [29]. They also mention the positive effects of music on the immune system by reducing stress, which may mitigate AD-related neurodegeneration. Some authors propose the anxiety reduction induced by music, along with increased arousal or sustained attention, as mechanisms enhancing autobiographical memory [22].

The current state of research on music therapy as a treatment for AD shows positive results in addressing cognitive, psychological, and behavioral symptoms. However, there is limited evidence regarding the potential effects of music therapy on memory, despite memory loss being a central element of the disease present from its early stages [23].

The objective of this work is to conduct a systematic review of the current scientific research on the effects of music therapy as a non-pharmacological intervention on memory in patients with mild and moderate AD. Although episodic memory deficit is the primary symptom of AD, given that disease progression is not uniform and can result in deficits in other memory systems [4], the review will address memory in general. In particular, the specific objectives of this systematic review are the following: (1) To determine the effects of music therapy on memory in patients with mild and moderate AD. (2) To identify memory systems where music therapy has demonstrated efficacy in treating patients with mild to moderate AD. (3) To understand the different music therapy techniques applied in interventions for patients with AD.

We hypothesize that music therapy will have positive effects on memory preservation and the ability to evoke memories in individuals with mild to moderate AD. Additionally, we expect that music therapy interventions, whose goals and intervention strategies are defined and developed by music therapists, will have a superior effect compared to other types of musical interventions on memory in patients with AD.

2. Method

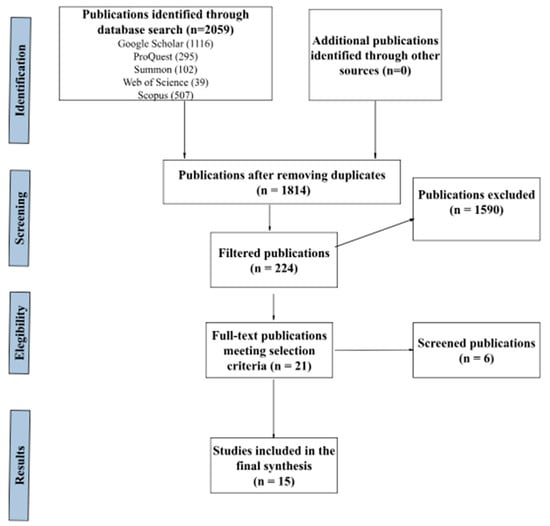

The search strategy is based on the criteria of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Starting from the PICOS (patient, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design) strategy, reflected in Table 1, the guiding question for the review was formulated. This approach allowed for a structured framework to ensure that all the critical aspects of the research were considered, including the specific characteristics of the patient population, the nature of the intervention being studied, comparison or control groups, the outcomes being measured, and the design of the studies included in the review.

Table 1.

PICOS.

The search for scientific articles was conducted using Boolean operators (“AND” and “NOT”), truncations (“music therapy” and Alzheimer), and the keywords Alzheimer, Alzheimer’s disease, music therapy, memory, musicoterapia, and memoria.

The search was performed in the databases Google Scholar, ProQuest, Summon, Web of Science, and Scopus, with the search completed on 30 December 2023. The search was limited to the last 10 years, and publications were included if they were in English or Spanish (criteria applied in the initial search). Additionally, in the ProQuest and Summon databases, the search was limited to full-text scientific journals.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria defined for the selection of scientific articles are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

The authors registered the manuscript in OSF. Madera-Cimadevilla, T., Cantero-García, M., & Rueda-Extremera, M. (10 July 2024). Systematic review. Music therapy Alzheimer’s disease. Retrieved from osf.io/gkfpt Systematic review. Music therapy Alzheimer’s disease. Retrieved from osf.io/gkfpt (accessed 12 July 2024).

Below is the explanatory diagram of the search and selection process based on the PRISMA 2020 (Figure 1) Statement [30].

Figure 1.

PRISMA-based systematic review process flowchart.

The screening process was conducted based on searching for duplicates in the references imported into the Refworks manager. Additionally, a review process of the articles by title was carried out, excluding duplicates not identified by the reference manager and other topics: articles covering other types of dementia (vascular, Lewy’s bodies…); studies on healthy individuals or those with other diseases (Parkinson’s, leukemia, cancer…); other types of interventions that do not include music therapy or music-based interventions (pharmacological treatments, cognitive therapies, art therapy…); publications that are not scientific articles (books, conferences, journalistic articles…); as well as references with no content or errors in the query.

The number of resulting studies was 15; these studies were found up to the indicated date and selected based on the previously mentioned method. However, it has been detected that one of the studies has been retracted by the publication, so it will not be included in the presentation of results and discussion [31].

3. Results

In Table 3, the selected articles are detailed. Additionally, the results related to the types of intervention and measurement instruments are included. Below, we present the results of the selected articles in relation to the objectives set for the systematic review.

Table 3.

Publications included in the systematic review on the effects of music therapy on memory in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

3.1. Effects of Music Therapy on the Memory of Patients with Mild and Moderate AD

Out of the 15 articles reviewed, 2 do not show favorable results, or the effects cannot be considered significant [40,41], while 13 present the positive effects of music therapy, or music-based interventions, on different memory systems in patients with AD.

We found research where patients with AD exhibit a performance similar to healthy controls in various memory assessment tests after music intervention, indicating their preservation. Basaglia-Pappas et al. [33] point out that these results occur for some components of musical memory but not for others. Cuddy et al. [34] compare the results of patients with AD with healthy older adults and younger adults, noting that patients with AD show age-related effects but not disease-related effects in their ability to recall memories. El Haj et al. [35] infer that patients with AD have a greater capacity to recall memories when exposed to music than when in silence. However, the performance on episodic memory tests of the experimental group of patients with AD is worse than that of the healthy control groups. El Haj et al. [36] report better results for the ability to recall memories in patients with AD when the music is chosen by themselves than when chosen by the researcher. Simmons-Stern et al. [44] conclude that both patients with AD and healthy controls remember general content information studied in song lyrics better when sung than when spoken, while memory for specific content does not benefit from musical accompaniment.

In the research conducted by Arroyo-Anlló et al. [32], Gómez et al. [39]), and Zhang and Liu [45], where patients with AD are randomly assigned to experimental groups and control groups without intervention or with other types of interventions, an improvement in memory after music intervention is observed in the experimental subjects compared to controls. In the case of the articles by Giovagnoli et al. [37] and Lyu et al. [41], the positive effects are maintained in the short term but not in the follow-ups conducted three months after treatment.

Finally, some articles show the results of music therapy interventions on the same group of patients with AD before and after the intervention. Gómez and Gómez [38] point out the positive effects of music therapy on memory, while Ponce et al. [42] indicate positive effects on the ability to recall autobiographical memories, as well as on the semantic component of autobiographical memory, but not on the episodic component.

Regarding the different stages of the disease, interventions are primarily targeted at patients diagnosed with mild to moderate AD, although two articles [34,41] include interventions on patients with severe AD as well. The results do not allow determining the effectiveness of interventions in different stages of the disease since they are presented collectively, without specifying the group of patients on which they have had an effect based on this criterion.

3.2. Memory Systems in Which Music Therapy Has Shown Effectiveness in Treating Patients with AD

We found that 8 out of the 15 articles focus their research on the autobiographical and episodic memory systems, which are typically most affected in patients with AD.

The study conducted by Basaglia-Pappas et al. [33] investigates autobiographical memory related to musical memory, concluding that both patients with AD and healthy controls can evoke autobiographical memories after listening to a song. Furthermore, they note that semantic musical memory for popular songs appears to be preserved in patients with AD, showing similar results to controls for melodic and autobiographical memory related to songs, although weaker results in terms of semantic knowledge and autobiographical recall about the performer.

Cuddy et al. [34] and El Haj et al. [35] study the presence of music-evoked autobiographical memories (MEAMs) in patients with AD. Both studies conclude that music is an effective cue for the retrieval of autobiographical memories.

Musical interventions also show positive effects on autobiographical memory and the ability to evoke memories in the studies by El Haj et al. [36] and Ponce et al. [42]. The first two also include results on the semantic and episodic components of autobiographical memory. While Ponce et al. [42] find better results in the semantic component after the intervention, in El Haj et al.’s [36] study, this component does not benefit. Regarding the episodic component of autobiographical memory, no significant differences are observed in either investigation. Additionally, El Haj et al. [36] provide results on the self-defined component of autobiographical memory, with a higher percentage of memories than the other two components after the intervention.

Three of the articles yield results on the episodic memory system. In El Haj et al.’s [35] study, patients with AD show poorer performance than healthy controls in the episodic memory task. Giovagnoli et al. [37] indicate its preservation after music intervention in patients with AD, an effect that is not maintained in the long term. In Simmons-Stern et al. [44] study, patients with AD do not improve episodic memory for specific content but do for more general content information.

Research related to short-term and long-term memory processes differ in their results. In Li et al. [40], no significant differences are found after the intervention in patients with AD, while in Lyu et al.’s [41] study, music therapy has a positive effect on these processes, although it is not maintained for more than 3 months after the intervention.

Other memory systems showing the positive effects of musical interventions in patients with AD include prospective memory [32] and linguistic memory [45]. Regarding memory for everyday life, the intervention designed by Satoh et al. [43] does not seem to have effects on patients with AD.

In the studies conducted by Gómez and Gómez [38] and Gómez et al. [39], the results refer to memory in general, without specifying the memory system benefiting from music therapy in patients with AD.

3.3. Music Therapy Techniques Applied to Intervention in Patients with AD

The results related to music therapy techniques are detailed in Table 3. Following Raglio and Oasi’s [17] classification of music-based interventions, out of the 15 articles selected for review, 5 employ active and/or receptive music therapy techniques, specifying the involvement of a music therapist [37,38,39,41,42].

We found six articles where interventions are based on active music therapy techniques [43] and receptive music therapy [33,34,35,36,44], in which the therapists and/or researchers are involved in both music selection and intervention, but it is not specified if they are music therapists.

Lastly, three interventions are based on listening to music, with therapists and/or caregivers participating in playlist selection but not in intervention sessions [32,40,45].

4. Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) leads to the progressive impairment of episodic, autobiographical, and semantic memory and other memory systems as the disease advances. The findings from this review appear to support the use of music therapy or musical interventions as complementary therapy for memory-related symptoms in AD patients, potentially stabilizing the decline in different memory systems or enhancing their ability to evoke autobiographical memories. However, due to the limited number of articles meeting the inclusion criteria and thus included in the review, and the fact that two of them [40,43] did not find positive or significant effects on memory, the hypothesis regarding the positive effects of music therapy on memory in AD patients cannot be validated or refuted. Therefore, we believe the results pave the way for future research, rather than providing solid conclusions about its efficacy.

Regarding articles with unexpected results, it was noted that in both cases, the intervention period extended over 6 months, whereas in other studies, this period did not exceed 3 months, suggesting that the unfavorable outcomes could be due to the progression of cognitive decline in participants with AD during the process or to the fact that the effects did not endure over time. As highlighted by Satoh et al. ([43], p. 306), “we cannot determine if a longer intervention will produce a greater effect, or if disease progression will restrict further improvement.” It is worth noting that intervention effects also did not persist in long-term observations (3 months post-intervention) in the studies by Giovagnoli et al. [37] and Lyu et al. [41]. Therefore, time appears to be a significant variable (both the intervention period and long-term assessment) in determining the efficacy of music therapy or musical interventions on memory in AD patients.

Another aspect affecting the results, related to intervention techniques, is the use of individualized music versus music selected by researchers (disregarding subjects’ preferences or familiarity). Studies by Arroyo-Anlló [32] and El Haj et al. [36] compared the effects of these two experimental conditions, finding that memory performance was superior under conditions of individualized music compared to unfamiliar or researcher-selected music. These results align with findings from reviews by Barcia-Salorio [24] and Matziorinis and Koelsch [23], where the positive effects of music therapy on cognitive functions in AD patients were particularly evident when using subjects’ preferred music. Authors attribute this to the affective nature of familiar music [32], the personal meaning or emotional value of the songs chosen by the participants promoting relevant life memories [36], and the ability to process emotions through familiar melodies evoking autobiographical memories [38].

El Haj et al. [36] also demonstrated the superiority of effects of unfamiliar music over silence, corroborating findings by Irish et al. [22], which showed a significant improvement in autobiographical recall for AD individuals during researcher-selected background music compared to silence.

Overall, the impact of musical interventions on memory in AD patients appears to be more effective with individualized music compared to researcher-selected music, with both conditions surpassing silence. However, this aspect seems less influential on outcomes compared to intervention duration, as highlighted by Li et al. [40], where music’s effects on memory did not exceed those of silence, and Satoh et al. [43], which, despite using individualized music, did not show positive effects on memory in the long term.

Throughout the systematic review, a wide heterogeneity of music-based interventions was observed, reflecting various factors such as the defined theoretical and therapeutic frameworks, intervention goals, the involvement (or lack thereof) of music therapists, patient participation levels, environmental contexts, and the music types employed [16]. Most interventions showed positive effects regardless of their design, suggesting that any type of music-based intervention could potentially induce beneficial effects on memory in AD patients. This practical aspect is particularly relevant, as it opens avenues for musical intervention in more advanced AD stages, where patients may not actively participate in therapist-led sessions but can benefit from listening to music that evokes emotions and memories [16,39]. Nonetheless, it is advisable that musical interventions are designed by qualified professionals, with detailed techniques and theoretical frameworks validated for specific intervention objectives.

Another noteworthy aspect from the results is the focus on the memory processes under study. Some, like prospective memory [32], musical memory [33], everyday life memory [43], and linguistic memory [45], only had one study, making conclusions on the efficacy of musical interventions on these memory structures in AD patients inconclusive. Similarly, due to contradictory findings in short-term and long-term memory studies [40,41], as well as episodic memory [35,37,44], clear conclusions cannot be drawn. Other studies [38,39] referred to memory in a generic sense, without specifying any particular system.

A consistent finding is the ability of music-based interventions to support autobiographical memory maintenance and evoke autobiographical memories in AD patients. Evidence and consensus exist in studies where evaluations involve tests requiring the retrieval of specific memory experiences at specific times [41], as well as the assessments of memories evoked by music [34,35,36]. MEAMs, as described by El Haj et al. ([35], p. 243), exhibit characteristics of involuntary memories, i.e., “they are more specific, accompanied by more emotional content and mood impact, retrieved faster, and involve less executive control than memories evoked in silence”, making this intervention type suitable for AD patients with potentially impaired executive function, among others.

Autobiographical memory refers to “memories we hold about ourselves and the world around us” ([4], p. 165). It helps create and maintain our self-representation, aids in daily problem-solving and learning from specific experiences, and supports socialization by evoking life memories [4]. Therefore, music therapy and music medicine as non-pharmacological interventions for maintaining and evoking autobiographical memories holds significant importance for the well-being of AD patients, not only for its ability to generate positive emotions and connect with others through memories but also as an integral part of self-concept and identity [22].

In terms of the methods and measurement instruments for assessing music therapy effects on memory in AD patients, the results reveal a wide variety of scales and measures evaluating different memory systems and aspects thereof.

As future directions, it is necessary to accumulate more evidence using rigorous methodologies focused on the effects of music therapy on memory in AD patients, employing valid and sensitive measurement tools for affected memory systems. Conducting a scoping review and meta-analysis would be essential to consolidate the findings and provide a comprehensive overview of the field. Investigating the underlying mechanisms of music’s effect on memory in AD patients to optimize interventions would be particularly insightful. Additionally, studying the effects of longer and more extended interventions with robust long-term follow-ups is crucial to determine their efficacy, as the current results do not support prolonged interventions or the maintenance of long-term effects.

Finally, we estimate that interventions based on the paradigm of autobiographical memories evoked by music (MEAMs) could be a good non-pharmacological treatment alternative for AD patients in more advanced stages of the disease. This is supported by the reported benefits in research, including improvements in well-being and the preservation of identity, lower interaction requirements compared to active music therapy interventions, and reduced demand on an executive function that may be impaired in these patients due to cognitive decline.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; methodology, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; software, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; validation, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; formal analysis, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; investigation, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; resources, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and MCG; data curation, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; writing—review and editing, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; visualization, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; supervision, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; project administration, T.M.-C., M.R.-E. and M.C.-G.; funding acquisition, NA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization—WHO. Informe Sobre la Situación Mundial de la Respuesta de la Salud Pública a la Demencia: Resumen Ejecutivo. 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/350993 (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- World Health Organization—WHO. Dementia. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría (APA). Guía de Consulta de los Criterios Diagnósticos del DSM 5; Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría: Arlington, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley, A.; Eysenck, M.W.; Anderson, M.C. Memoria y Envejecimiento. In Memoria; En Psychology Press, Ed.; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 327–350. [Google Scholar]

- El Haj, M. Memory suppression in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 37, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization—WHO. Alzheimer’s Disease: Help for Caregivers. 2006. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MNH-MND-94.8 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Confederación Española de Asociaciones de Familiares de Personas con Alzheimer y Otras Demencias—CEAFA. 2022. Available online: https://www.ceafa.es/es/el-alzheimer/el-tratamiento-farmacologico-y-nf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- López, Ó. Tratamiento farmacológico de la enfermedad de Alzheimer y otras demencias. Arch. De Med. Interna 2015, 37, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social—MSCBS. Plan Integral Alzheimer y Otras Demencias (2019–2023). 2019. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/docs/Plan_Integral_Alhzeimer_Octubre_2019.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Escarabajal, M. Intervención no Farmacológica en Pacientes con Demencia. 11° Congreso Virtual de Psiquiatría. Interpsiquis 2010. 2010. Available online: https://psiquiatria.com/trabajos/16cof645476.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- De los Reyes, J.; Aragón, R.; Lasprilla, J.C.A.; Arango, C.; Díaz, M.A.R.; Rodríguez, A.; Bartolome, M.V.P.; Perea, V.; Fernández, V.L. Rehabilitación cognitiva en personas con Enfermedad de Alzheimer. Psicol. Desde Caribe 2012, 29, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Koshimori, Y.; Thaut, M.H. New Perspectives on Music in Rehabilitation of Executive and Attention Functions. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, M.C.; Hazard, S.O.; Miranda, P.V. La música como una herramienta terapéutica en medicina. Rev. Chil. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2017, 55, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thaut, M.H.; Francisco, G.; Hoemberg, V. The Clinical Neuroscience of Music: Evidence Based Approaches and Neurologic Music Therapy. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 740329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscia, K. Definiendo la Musicoterapia, 3rd ed.; Barcelona Publishers: University Park, IL, USA, 2016; pp. 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Raglio, A.; Oasi, O. Music and health: What interventions for what results? Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradt, J.; Dileo, C.; Shim, M. Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD006908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, W.; Moltrasio, J. Una mirada neuropsicológica de la música en pacientes con demencias. In Semana de la Música y la Musicología: Cognición Musical: Estudios en Música, Mente y Cerebro, XIV; Universidad Católica Argentina, Facultad de Artes y Ciencias Musicales, Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega”: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salakka, I.; Pitkäniemi, A.; Pentikäinen, E.; Mikkonen, K.; Saari, P.; Toiviainen, P.; Särkämö, T. What makes music memorable? Relationships between acoustic musical features and music-evoked emotions and memories in older adults. PloS ONE 2021, 16, e0251692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J.-H.; Stelzer, J.; Fritz, T.H.; Chételat, G.; La Joie, R.; Turner, R. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2015, 138, 2438–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janata, P. The neural architecture of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 2579–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish, M.; Cunningham, C.J.; Walsh, J.B.; Coakley, D.; Lawlor, B.A.; Robertson, I.H.; Coen, R.F. Investigating the enhancing effect of music on autobiographical memory in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2006, 22, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matziorinis, A.M.; Koelsch, S. The promise of music therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1516, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcia-Salorio, D. Musicoterapia en la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Psicogeriatría 2009, 1, 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch, S. A coordinate-based meta-analysis of music-evoked emotions. NeuroImage 2020, 223, 117350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelsch, S.; Jacobs, A.M.; Menninghaus, W.; Liebal, K.; Klann-Delius, G.; Von Scheve, C.; Gebauer, G. The quartet theory of human emotions: An integrative and neurofunctional model. Phys. Life Rev. 2015, 13, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strange, B.A.; Witter, M.P.; Lein, E.D.S.; Moser, E.I. Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, L.; Mas-Herrero, E.; Zatorre, R.J.; Ripollés, P.; Gomez-Andres, A.; Alicart, H.; Olivé, G.; Marco-Pallarés, J.; Antonijoan, R.M.; Valle, M.; et al. Dopamine modulates the reward experiences elicited by music. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3793–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verghese, J.; Lipton, R.B.; Katz, M.J.; Hall, C.B.; Derby, C.A.; Kuslansky, G.; Ambrose, A.F.; Sliwinski, M.; Buschke, H. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2508–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International, E.M. Retracted: Clinical Observation of Computer Vision Technology Combined with Music Therapy in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Emerg. Med. Int. 2023, 2023, 9783534. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Anlló, E.M.; Díaz, J.P.; Gil, R. Familiar music as an enhancer of self-consciousness in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 752965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaglia-Pappas, S.; Laterza, M.; Borg, C.; Richard-Mornas, A.; Favre, E.; Thomas-Antérion, C. Exploration of verbal and non-verbal semantic knowledge and autobiographical memories starting from popular songs in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddy, L.L.; Sikka, R.; Silveira, K.; Bai, S.; Vanstone, A. Music-evoked autobiographical memories (MEAMs) in Alzheimer disease: Evidence for a positivity effect. Cogent Psychol. 2017, 4, 1277578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haj, M.; Fasotti, L.; Allain, P. The involuntary nature of music-evoked autobiographical memories in Alzheimer’s disease. Conscious. Cogn. 2012, 21, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Haj, M.; Antoine, P.; Nandrino, J.L.; Gély-Nargeot, M.; Raffard, S. Self-defining memories during exposure to music in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovagnoli, A.R.; Manfredi, V.; Parente, A.; Schifano, L.; Oliveri, S.; Avanzini, G. Cognitive training in Alzheimer’s disease: A controlled randomized study. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Gómez, J. Musicoterapia en la enfermedad de Alzheimer: Efectos cognitivos, psicológicos y conductuales. Neurología 2017, 32, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Gómez, J.C.; Gallego, M.; García, J. Comparative efficacy of active group music intervention versus group music listening in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.H.; Liu, C.K.; Yang, Y.H.; Chou, M.C.; Chen, C.H.; Lai, C.L. Adjunct effect of music therapy on cognition in Alzheimer’s disease in Taiwan: A pilot study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Zhang, J.; Mu, H.; Li, W.; Champ, M.; Xiong, Q.; Li, M. The effects of music therapy on cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, A.; Acosta, P.; Cruz, J.; Ramos, C. Music stimulation as a method of optimizing autobiographical memory in patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 678–687. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, M.; Yuba, T.; Tabei, K.I.; Okubo, Y.; Kida, H.; Sakuma, H.; Tomimoto, H. Music therapy using singing training improves psychomotor speed in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A neuropsychological and fMRI study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 2015, 5, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons-Stern, N.R.; Deason, R.G.; Brandler, B.J.; Frustace, B.S.; O’Connor, M.K.; Ally, B.A.; Budson, A.E. Music-based memory enhancement in Alzheimer’s disease: Promise and limitations. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 3295–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, M. The effects of continuing care combined with music therapy on the linguistic skills, self-care, and cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 13, 9621–9627. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).