Time Out: The Built as a Refuge from the Temporal

Abstract

1. The Present as an Escape from Time

We live from that which is no more toward that which is not yet through a slender, fragile boundary called now that is too fugitive ever really to be laid hold of. Where, then, is time?… The present alone exists, located in the mind, and having three foci: a present memory of past events, a present attention to present events, and a present anticipation of future events[6] (pp. 63)

2. The Duration of Now

Chronos is the objective view of time… In the world of chronos, the present instant is a moving point in time headed only toward the future… It is an almost infinitesimally thin slice of time during which very little could take place without immediately becoming the past. Effectively, there is no present.

The problem with chronos is that if there is no now long enough that something can unfold in it, there can be no direct experience. That is not intuitively acceptable. Also, life-as-lived is not experienced as an inexorably continuous flow. Rather, it is felt to be discontinuous, made of incidents and events separated in time

The Greeks’ subjective conception of time, kairos, may be of use here. Kairos is the passing moment in which something happens… It is the coming into being of a new state of things, and it happens in a moment of awareness… It is a small window of becoming and opportunity[15] (p. 7).

3. Fascination

There were times when I could not afford to sacrifice the bloom of the present moment to any work, whether of the head or hand. Sometimes, in a summer morning, having taken my accustomed bath, I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in a revelry, amidst the pines and hickories and sumacs, in undiluted solitude and stillness, while the birds sang around or flitted noiseless through the house, until by the sun falling in at my west window, or the noise of some traveler’s wagon on the distant highway, I was reminded of the lapse of time[16].

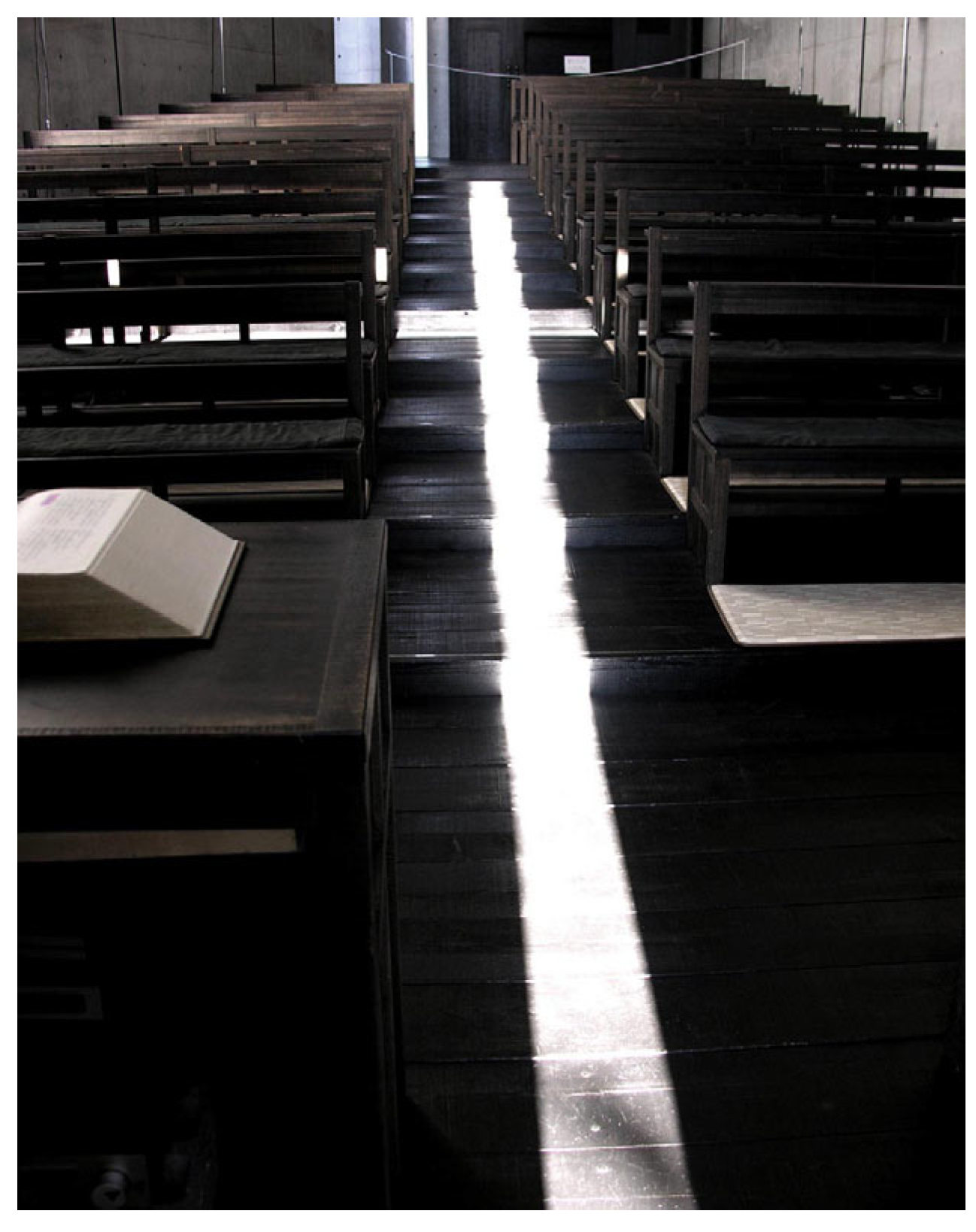

Perhaps the human fascination with fire stems from the totality of its sensory stimulation. The fire gives a flickering and glowing light, ever moving, ever changing. It crackles and hisses and fills the room with smells… It penetrates us with its warmth. Every sense is stimulated, and all their associated modes of perception, such as memory and awareness of time, are also brought into play… Together they create such an intense feeling of reality, of the “here and nowness” of the moment, that the fire becomes completely captivating[18].

4. Natural Change in Built Environments

5. The Perpetual Present

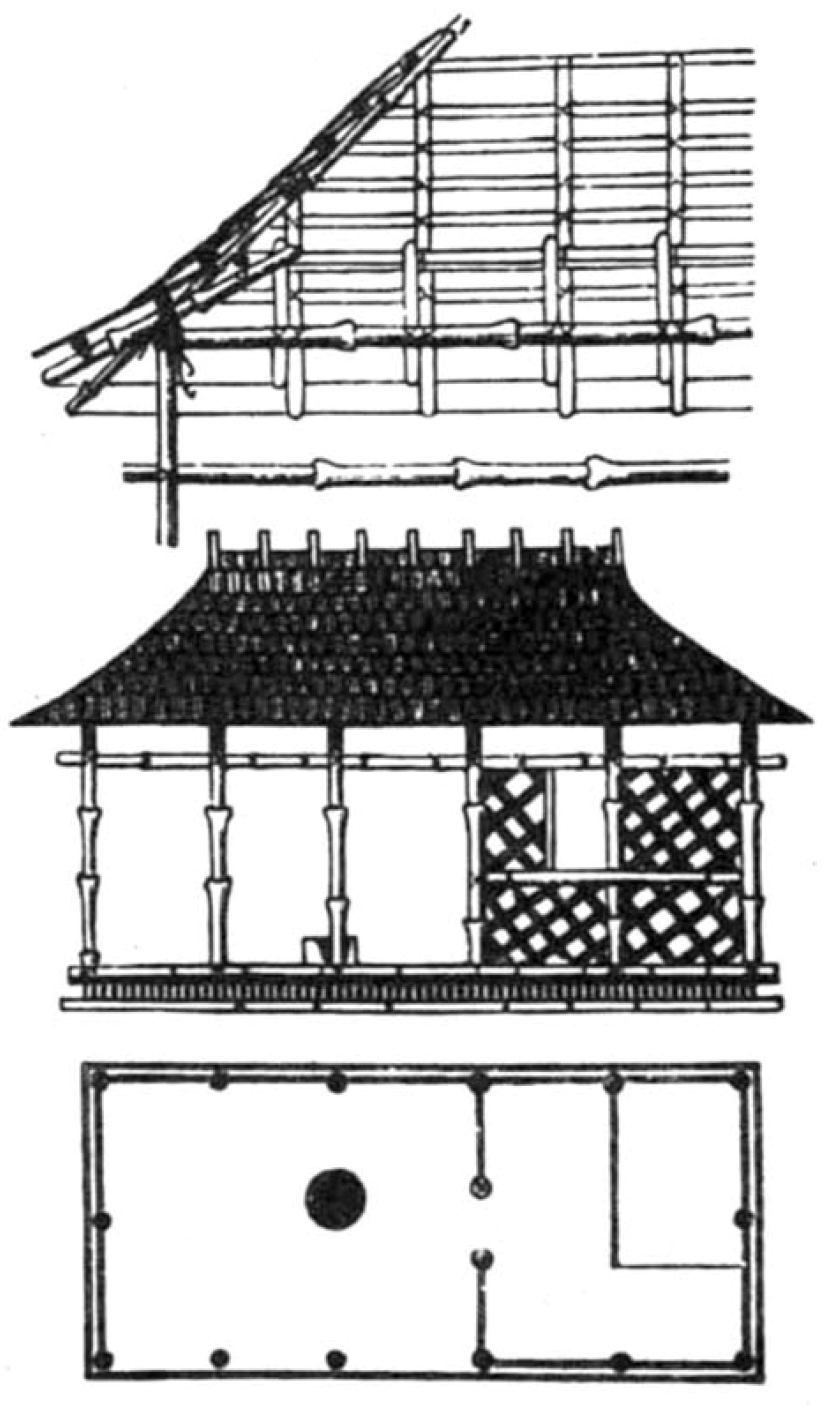

6. Timeless Forms

This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes.

[instincts] form very close analogies to the archetypes, so close, in fact, that there is good reason for supposing that the archetypes are the unconscious images of the instincts themselves, in other words, that they are patterns of instinctual behavior[29].

7. Isolation

8. The Presence of the Body

9. Initiating Change

10. Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spencer, H. The Dictionary of Essential Quotations; Goldstein-Jackson, K., Ed.; Croom-Helm: London, UK, 1983; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer, I. The Trauma of Time: A Psychoanalytic Investigation; International Universities Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Harries, K. Building and the Terror of Time. Perspecta Yale Archit. J. 1982, 19, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, A.M.; Meyvis, L.; Nelson, D.; Converse, B.A.; Sackett, A.L. You’re Having Fun When Time Flies: The Hedonic Consequences of Subjective Time Progression. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 2, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snodgrass, A. Architecture, Time and Eternity: Studies in the Stellar and Temporal Symbolism of Traditional Buildings; Goel, P.K., Ed.; Aditya Prakashan: New Delhi, India, 1990; Volume 1, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass, A. Architecture, Time and Eternity. Aditya Prakashan: New Delhi, India, 1990; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, J.N.; Atkins, P.W.; Parker, P.D.; Christie, A.M.; Ryan, R.M. Daily Stress and the Benefits of Mindfulness: Examining the Daily and Longitudinal Relations Between Present-Moment Awareness and Stress Responses. J. Res. Pers. 2016, 65, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W. The Principles of Psychology; Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1890; Volume 1, p. 609. [Google Scholar]

- Bergson, H. Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness; Pogson, F.L., Translator; George Allen & Company: London, UK, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Gideon, S. Space, Time and Architecture: The Birth of a New Tradition; Harvard UP: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eyck, A. Place and Occasion. Progress. Archit. 1962, 43, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eyck, A. The Interior of Time. The Child, The City and the Artist: An Essay on Architecture, the In-Between Realm; Ligtelijin, V., Strauven, F., Eds.; Sun: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. What Time Is This Place? MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D.A. The Present Moment in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life; W. W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thoreau, H.D. Walden: Or Life in the Woods; The Heritage Press: New York, NY, USA, 1939; pp. 117–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Heschong, L. Thermal Delight in Architecture; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, T. Introduction, Tadao Ando: Buildings, Projects, Writings; Frampton, E., Ed.; Rizzoli International: New York, NY, USA, 1984; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, T. The Eternal Within the Moment. In Tadao Ando: Complete Works; Cao, F.D., Ed.; Phaidon Press: London, UK, 1995; p. 474. [Google Scholar]

- Nute, K.; Weiss, A.; Kaur-Bala, J.; Marrocco, R. The Animation of the Weather as a Means of Helping to Sustain Building Occupants and the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 8, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nute, K.; Chen, Z.J. Wind-Generated Movement as a Potential Means to Psychological Presence in Indoor Work Environments. Int. J. Des. Soc. 2020, 14, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. A Beat of the Rhythmic Clock of Nature: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Waterfall Buildings. In Fallingwater and Pittsburgh; Menocal, N.G., Ed.; Wright Studies, Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA; Edwardsville, IL, USA, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, N. The Temporal Dimension of Fallingwater. In Fallingwater and Pittsburgh; Menocal, N.G., Ed.; Wright Studies, Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA; Edwardsville, IL, USA, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 32–79. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness; Churchill, J.S., Translator; Indiana University Press: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, M. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion; Willard, R.T., Translator; Harcourt Brace: New York, NY, USA, 1959; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, M. The Myth of the Eternal Return: Or Cosmos and History; Trask, W.R., Translator; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1971; pp. 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, M. The Myth of the Eternal Return (1949); Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1954; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.G. Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious: Collected Works of C.G. Jung; Adler, G., Jung, C.G., Hull, R.F.C., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1981; Volume 9, pp. 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- The Four Elements of Architecture. In The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings; Semper, G., Ed.; Mallgrave, H.F.; Hermann, W., Translators; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. The Timeless Way of Building; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M.; Fiksdal-King, I.; Angel, S. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Okakura, K. The Book of Tea [1906]; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1964; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Bergson, H. Matter and Memory; Paul, N.; Scott Palmer, W., Translators; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1913; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Report to Congress on Indoor Air Quality; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; Volume 2.

- Roberts, T. We Spend 90% of Our Time Indoors. Says Who?: Where the Oft-Quoted Statistic Comes from, and What the Underlying Study Says About Health in Buildings. Building Green, 15 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, H. The Experience of Architecture; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2016; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Nute, K. Embodied Time: Temporal Cues in Built Spaces; World Scientific: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nute, K. Time Out: The Built as a Refuge from the Temporal. Architecture 2025, 5, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040090

Nute K. Time Out: The Built as a Refuge from the Temporal. Architecture. 2025; 5(4):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleNute, Kevin. 2025. "Time Out: The Built as a Refuge from the Temporal" Architecture 5, no. 4: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040090

APA StyleNute, K. (2025). Time Out: The Built as a Refuge from the Temporal. Architecture, 5(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040090