1. Introduction

The 15-minute city is an urban planning concept popularized by Carlos Moreno [

1,

2] where residents can meet most of their daily needs—work, education, shopping, healthcare, and leisure—within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from their homes. It has been adopted by cities such as Paris, Barcelona, Melbourne, Portland, Shanghai, and Pontevedra in ways that go beyond spatial convenience towards broader livability, including introducing urban planting and car-free spaces, to improve the connection between people and nature, lower Co2 emissions, and encourage a healthy lifestyle [

3]. Local in application, the concept responds to ‘the cause-and-effect links between urban lifestyles, economic development, modes of transport, climate change, and the malaise of residents’ [

4], acknowledging the interconnectedness of health, wellbeing and the designed environment. As such, Moreno argues that ‘the 15 min city offers a new framework for sustainability, livability, and health’ [

5].

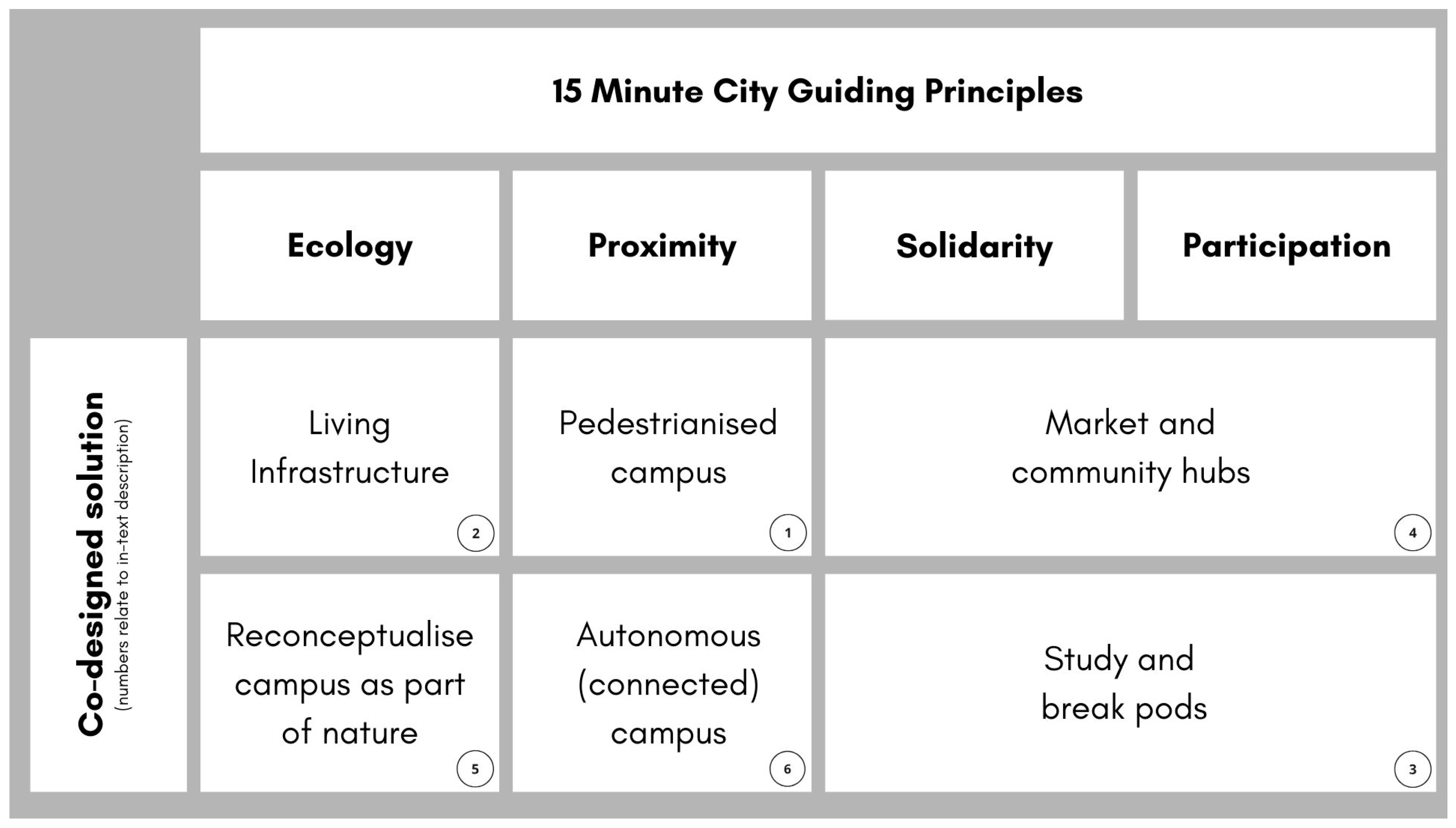

The 15-minute city (15 mc) concept as described by Moreno (2021) [

6] is underpinned by broad goals, to be applied through four guiding principles [see

Figure 1]. The broad goals which define a good city are outlined: a focus on humans not cars; an emphasis on multi-use spaces which serve many different purposes; and an emphasis on neighborhoods as spaces where people can live and thrive, without having to constantly commute elsewhere (typically by car). This is enacted through four guiding principles:

Ecology: for a green and sustainable city;

Proximity: to live with reduced distances to other activities;

Solidarity: to create links between people; and

Participation: to engage citizens in the transformation of their neighborhoods [

6]. This research enacts these four principles, including the often-overlooked principles of ecology, solidarity and participation, by exploring design ideas for a university campus in participation with campus users.

When the 15-minute city concept is translated to a university ‘campus’, students and staff should be able to access classrooms, libraries, dining, housing, and recreational facilities within 15 min of active travel (typically considered to be a walk or bike ride). But, as the four guiding principles outline, the concept is about much more than just proximity, it allows us to think about mixed-use spaces for studying and leisure, how well-connected campus spaces are to wider ecological as well as transport networks, how inclusive the campus is for everyone, how sustainable our spaces can be, and the impacts that this might have on both human wellbeing and biodiversity [

7]. The value of integrating these aspects of campus design is highlighted as being ‘a critical foundation for spatial justice, student wellbeing, and sustainable transformation’ [

8].

University campuses are an important context to investigate the 15-minute city because they: potentially impact over 260 million students [

9]; offer a contained microcosm of aspects of the wider city; and because mobility to and around the campus has significant implications on students’ ability to access education. There is increasing recognition that university campuses ‘do more than accommodate; they shape identity, engagement, and belonging’ for students [

10]. In parallel, there is an urgent need to upgrade university estates to respond to sustainability demands, indeed the European Commission highlights that ‘modern University campus estates need to be retrofitted and transformed to promote sustainable mobility and living…They play a central role in spurring infrastructure improvements…This revitalization can enhance the quality of life for both students and city residents.’ [

11]. Amid escalating concerns over climate change, mental health, and biodiversity loss, higher education institutions have a vital role to play in reshaping urban environments, both as places which can occupy up to 20% of a city’s land (for Oxford and Cambridge Universities for example) and as places of knowledge, societal and cultural production.

While university campuses hold significant potential to embody the principles of the 15-minute city—and in many ways, already function as archetypes of this ideal—there remains a notable gap in research specifically examining the concept within the context of university estates. There is a paucity of research on the 15-minute city in university campus settings, despite the huge number of people they affect worldwide. The sole existing published work to date on how the 15-minute city might be applied to university campuses has also identified the potential ‘to reduce carbon emissions, enhance civic engagement and improve the vibrancy and liveability of cities’ [

12]. More broadly, existing studies of the 15-minute city tend to be quantitative in nature [

13] and focus primarily on transport and proximity [

3], often overlooking the more holistic integration of the four guiding principles of the 15-minute city: ecology, proximity, solidarity, and participation. In addition, city planning more broadly has been criticized for ignoring young people, especially older youth who are often invisible or relegated to deficit categories rather than proactive participants, and being too top-down [

14].

Addressing both the existing research gap and critiques of technocratic top-down planning, this study aims to work co-creatively with campus-users to generate design ideas for how the 15-minute city framework can be applied to university settings. Since the only study identified to date focuses on active travel [

12], the research presented here is the first published attempt to holistically conceptualize the 15-minute campus as a co-created design application of 15-minute-city principles. Using participatory design research grounded in regenerative approaches, this paper investigates the potential impacts of 15-minute city principles on biodiversity, health, and wellbeing, within campus environments.

2. Literature Review

The concept of the 15-minute city has gained global attention for its potential to enhance urban sustainability, health, and wellbeing, yet its implementation—particularly in localized contexts such as university campuses—requires some contextualization. Where the 15-minute city ideas have been applied, initial improvements in lifestyle, livability, health indicators and environmental benefits have already been recorded, see Pontevedra [

2], Paris, and Barcelona [

7]. Research comparing 700 cities worldwide shows that cities with superior walking accessibility tend to produce lower per capita transport CO

2 emissions, aligning improved compactness with reduced environmental impact [

15]. From a health equity perspective, the model is found to foster increased physical activity, social capital, and reduced car dependency, all of which benefit mental and physical wellbeing [

16]. However, the framework has yet to fully address biodiversity goals—systematic reviews highlight that while the concept emphasizes proximity and human-scale design, it overlooks ecological dimensions including urban habitat protection and energy-efficient infrastructure [

17].

It is worth noting that the four principles outlined by Moreno used in this paper (ecology, proximity, solidarity, and participation) have subsequently been amended by Moreno to proximity, diversity, density and ubiquity in some publications [

18], and to density, proximity, diversity and digitalization [

19], which, after the COVID-19 pandemic, introduced a digital element to accessibility. A historic review paper on the 15-minute city concept presented up to ten characteristics: 1—proximity, 2—density, 3—diversity, 4—mixed-use, 5—modularity, 6—adaptability, 7—flexibility, 8—human-scale design, 9—connectivity, and 10—digitalization [

17]. Moreno’s model is arguably the most explicitly equity-driven (via the terms solidarity, participation, and later ubiquity), whereas other versions often swap in connectivity or walkability as a principle, or pivot to activity-based definitions. These variations usually tailor the principles to a specific policy area—transport, land-use planning, or service delivery—sometimes at the cost of the Moreno’s strong social justice framing. Shifts also highlight a subsequent shift away from the focus of ecology from the four principles that we used in this research, suggesting that, for some reason, ecological aspects have largely been excluded from more recent debates.

In parallel, there is some controversy over the concept, as conspiracy theorists have suggested it is a way to limit people’s freedom of movement by containing people within 15 min neighborhoods and forcing people out of their cars, with the associated threat to personal liberties [

20]. This concern has led to protests, as typified by the protests in Oxford in 2022 and 2023 [

8]. Although there is no intention in any of the theories or applications to enact that kind of control (rather the approaches are actually about working with communities and expanding the range of travel and experience options), it is perhaps not surprising after the lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic that the prospect of limiting freedoms were very tangible. Scholars caution that equitable implementation is vital to avoid unintended consequences like displacement [

21], which could also feed into negative impacts or interpretations of the approach.

The application of the 15-minute city concept to university estates and campuses has been under-explored. To date, there is only one identified academic paper from 2023 which argues for adopting the 15-minute city approach on city-based university campuses. This proposes a shift from the traditional “sticky campus” to a more outward-looking “15-minute campus,” emphasizing: porous boundaries to encourage shared services between campuses and communities; active evaluation and improvement of the surrounding public realm; and promotion of high-quality public transport and active travel infrastructure. These, they argue, can help reduce carbon emissions, improve civic engagement, and enhance vibrancy and livability [

12].

Despite the limited research on 15-minute campus, there is broader research which suggests that university campuses might be ideal locations for affecting biodiversity, health and wellbeing. A global review found that campuses support substantial biodiversity—averaging around 199 plant species and 66 bird species per site—highlighting their potential role in urban conservation and public engagement with nature [

22]. Empirical evidence from a Chinese university demonstrates that different campus landscapes, ranging from lakeside lawns to shaded rooftop corridors, are variably associated with increased happiness and stress reduction, with frequently visited or visually accessible green spaces offering the strongest wellbeing benefits [

23]. Further research shows that campus green spaces can significantly enhance students’ mental health, often exceeding the impact of academic achievement alone, and can act as mediators of stress and depressive symptoms [

24]. Finally, experimental research indicates that sensory impacts of biodiversity, such as birdsong and plant species richness, promote psychological restoration and reduce physiological stress, even through visual or auditory exposure alone [

25]. These findings suggest that campus design, integrating diverse, accessible natural environments, supports both ecological richness and human health. As such, it is valuable to explore the campus as a designed environment, and one that has the potential to have positive impacts on biodiversity, health, and wellbeing. The 15-minute city lens in particular enables a holistic approach to thinking about campus design, which draws on the four guiding principles of ecology (for a green and sustainable city); proximity (to live with reduced distances to other activities); solidarity (to create links between people); and participation (to engage citizens in the transformation of their neighborhoods) [

6].

3. Materials and Methods

The research is innovative in its exploration of the 15-minute city on university campuses through participatory design research (see

Figure 1). This approach ‘encompasses research designs, methods, and frameworks…in direct collaboration with those affected by an issue being studied’ [

26]. The novelty of this initiative lies in the participatory co-creative design process, which allows holistic design explorations of the key aspects of the 15-minute city concept. As such, this study adopts a participatory design research approach, which foregrounds co-creative methods and situated knowledge as key to the 4 principles underpinning the 15-minute city concept [

6]. Participatory processes are also a key component of the 15-minute city practice, for example, in Paris ‘Citizen participation is at the heart of the city’s quarter-hour strategy’ which allows residents of the city ‘to help …think about and build the Paris of tomorrow’ [

4]. Mehan and Dominguez (2024) highlight the importance of co-design involving students in creating accessible and sustainable environments [

27]. Hager (2025) argues that in ‘a truly inclusive 15-minute-city, planning is not a top-down exercise but a collaborative dialogue’ [

28]. The participatory approach of this research thus incorporated bottom-up student participation, and holistic ‘big picture’ thinking.

Rooted in democratic and co-creative traditions, participatory research actively involves stakeholders (in this case students, staff and other users of the campus)—not merely as subjects of research, but as co-designers and co-creators of knowledge [

26]. It is a well-established approach in fields such as health [

29] and architecture/placemaking [

30] and is increasingly being adopted across a range of other research disciplines [

31]. Participatory design research goes beyond consultation, by embedding participants in a co-creative design process as a way of generating knowledge and sharing new insights. It resists the separation between experts and non-experts and challenges top-down, expert-led models by valuing diverse voices, especially those traditionally marginalized or underrepresented in decision-making processes. This approach aligns with the regenerative principles which underpinned the research—moving beyond the sustainable principle of ‘do no harm’ towards healing and restoration.

Regenerative approaches (see

Figure 2) were introduced through the co-creative process to bring the ecological and broadest regenerative principles of the initial 15-minute city ideals into focus. Regenerative principles are grounded in an ecological worldview which uses ‘living and whole systems theory…with the goal of creating co-evolution between human and natural systems’ [

32] and utilize living and whole systems theory to underpin initiatives with the goal of creating co-evolution between human and natural systems [

33,

34] and including non-humans [

35]. Using these techniques emphasized equity and long-term impact over efficiency or narrow investigations (such as those, for example, that simplify the 15-minute city to look at transport alone).

In this study, students, staff, and community stakeholders were engaged through design—including regenerative design-thinking workshops, mapping exercises, and speculative design sessions alongside wider stakeholder engagement—to explore the possibilities of a 15-minute campus. Three key aspects of Camrass’ regenerative principles were used to structure the activities [see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2] including responding to the ‘story of place’, developing shared future metaphors, and backwards mapping from a desired regenerative future [

32]. Although the full 8 regenerative principles were introduced to co-creators, these three were picked out as being most applicable to prompt design responses in the co-created design process.

The research was embedded in Birmingham City University (BCU) Eastside campus as a case study, which allowed for an in-depth, context-sensitive exploration of the complex, real-world phenomena [

36] of a university campus. The case study approach is particularly appropriate when undertaking participatory research in bounded systems, such as university campuses, where multiple variables interact in dynamic and context-specific ways [

37]. The BCU campus presents a diverse urban fabric of educational buildings, roads, live construction (HS2—the UK’s controversial High Speed rail link), and underused spaces [see

Figure 3]. The case study site is an ‘Urban Campus’ embedded within the city center, with buildings clustered together but not separated from the urban environment [

38].

The participatory design research was undertaken over the course of ten weeks, from January to April 2025 through a ‘Collaborative Laboratory’ (CoLAB); an award-winning design and research initiative embedded across BCU’s Architecture department. CoLAB was specifically developed to allow the co-creation and co-production of creative trans-disciplinary projects with undergraduate and postgraduate students working collaboratively with staff and external partners [

39]. Through the CoLAB vehicle, a mixed group of 18 Bachelors and Masters students (studying architecture, landscape architecture and interior architecture) and 2 staff participated in a program of co-creative design workshops. These worked in consultation with the university’s sustainability team and the Pro Vice Chancellor and Executive Dean for Sustainability and involved wider engagement with students, visitors and staff using the campus. By directly co-creating with students of architecture, interior architecture and landscape architecture, and further engagement with other campus users including visitors, students and staff, the research explored potential visions for the 15-minute campus.

The key components of this ‘Collaborative Laboratory’ (CoLAB) were facilitated through co-creative design workshops; the workshops followed three phases to respond to Camrass’ regenerative principles [

32] to develop stories of place, shared future metaphors and backwards mapping (see

Figure 4).

Stories of place: The approach started with short co-creative workshops exploring the existing stories of place for the campus. Camrass proposed that ‘regenerative practice starts with a story of place that considers nested human and natural systems and incorporates a layered understanding of reality and time.’ This took the form of 15-minute self-guided group walks from the center of the campus, to identify what was there, what could be valued, and what were the barriers and problems, with an emphasis on recording both the human and non-human. The activity inspired ‘deep listening’ and ‘an ability to incorporate multiple perspectives’ [

1] using inspiration from psychogeographical mapping (which emphasizes recording how people feel and navigate through space—beyond functional or official maps). These were used as a participatory and interpretive tool to surface emotional, embodied, and experiential relationships to campus spaces. Inspired by Situationist dérives and developed through contemporary walking methodologies, participants mapped their affective responses, sensory impressions, and spatial narratives [

40]. As part of this process participants created individual ‘gifts’ for the campus (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). These are inspired by Kimmerer who describes ‘Gratitude and reciprocity are the currency of a gift economy, and they have the remarkable property of multiplying with every exchange, their energy concentrating as they pass from hand to hand, a truly renewable resource’ [

41].

These gifts allowed more personal responses to the existing campus stories of place, which began to prompt ideas for dialog in developing a collective co-created response. These maps and gifts became both data and dialog—revealing patterns of exclusion, comfort, and ecological connection, and informing the thinking in the next phase.

Shared future metaphors: Building on the stories of place, a series of interactive engagement activities were conducted in a shared campus thirdspace, to explore and co-create shared metaphors for the future of the campus. At this stage, the research expanded to engage more widely with campus users. Participatory idea walls were generated, (

Figure 7), which allowed a diverse range of stakeholders, including students, academic and professional staff, and members of the public to engage visually to share their aspirations for the future campus. This initiated a range of open-ended discussions about the future campus alongside a ‘suggestions box’ for people to drop their thoughts, with the prompts: ‘what is successful about the campus for you?’; ‘what is missing from the campus?’; and ‘what would your dream university campus include?’ These collective responses were brought together and analyzed through the Co.LAB group workshops to extract key shared future ideas.

In this way, the data analysis itself was also participatory and collaborative, offering an opportunity to integrate inclusive and transparent data interpretation. These ideas were brought together through design charettes [

42] which allowed participants to come together through brainstorming, visualization, prototyping, and facilitated discussion to co-develop solutions to respond to the 15-minute campus challenge within a 3 h workshop. The outputs took the form of conceptual masterplans for the campus within which specific design solutions were situated, as discussed below. The conceptual frameworks provide a ‘big idea’, a generative narrative to engage stakeholders and drive the project forward, described by Moore (2010) as ‘a powerful mechanism, a tool to help the designer make decisions inventively, to prompt the consideration of different possibilities and build the confidence to ask “what if?” and “why not?” rather than follow the line of least resistance’ [

43].

Backwards mapping: As part of the participatory design methodology, the final stage of the process employed backwards mapping—a strategic planning approach that begins with the articulation of a desired future state (as identified in the shared future metaphors) and works in reverse to identify the necessary steps and conditions required to reach it [

36]. In this context, backwards mapping was used to collaboratively envision a regenerative university campus. The process involved facilitated engagement with the university’s sustainability team and representatives from the chancellery, recognizing their complementary roles in shaping policy, infrastructure, and long-term institutional vision. This approach initiated a reflection on how the regenerative future for the campus might be realized, tracing back to a routeway of policy, spatial and behavioral changes needed to make that happen. It served not only as a design tool but also as a mechanism for engagement between stakeholders at different levels of influence.

5. Analysis and Discussion: Impacts on Biodiversity, Health, and Wellbeing

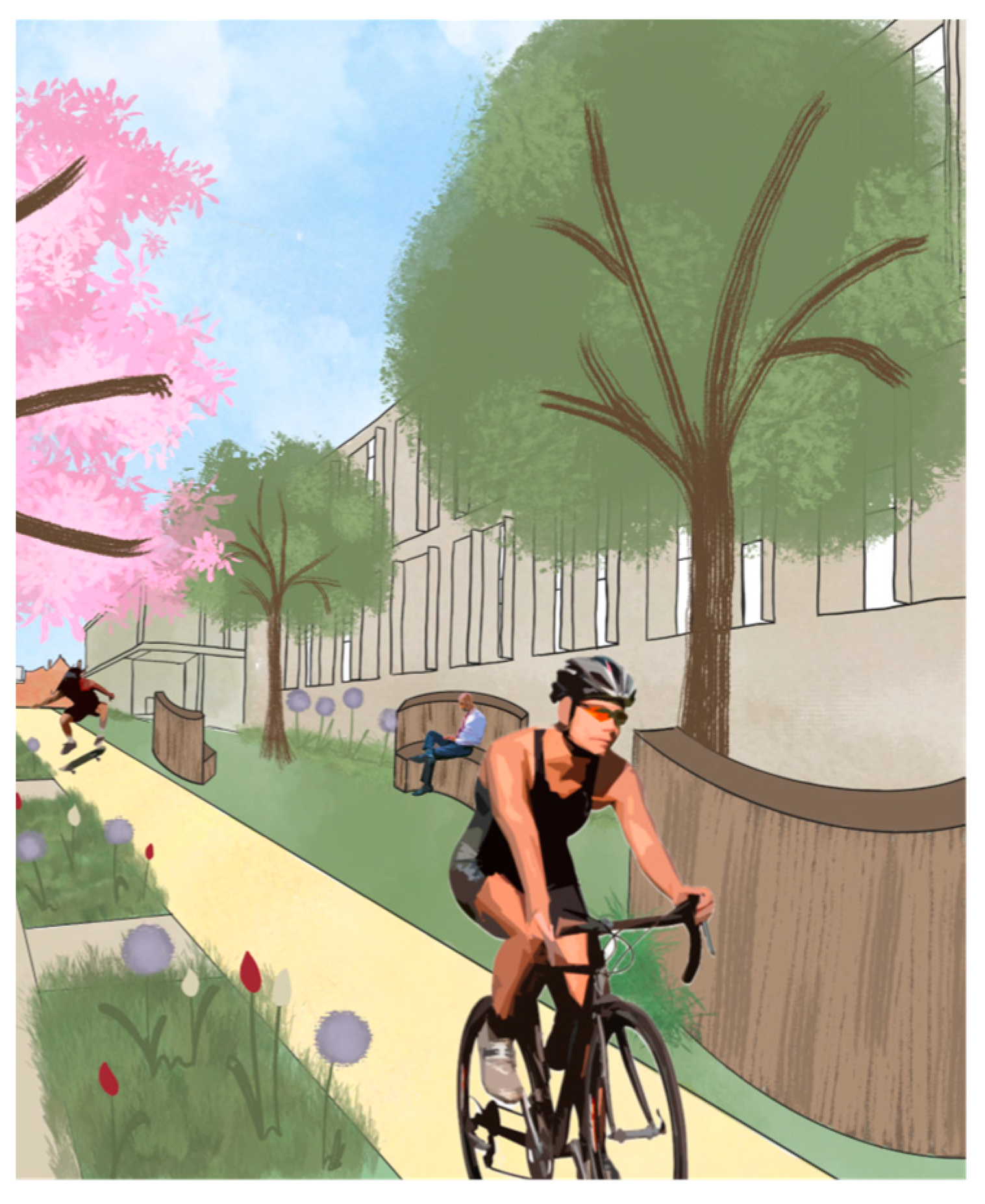

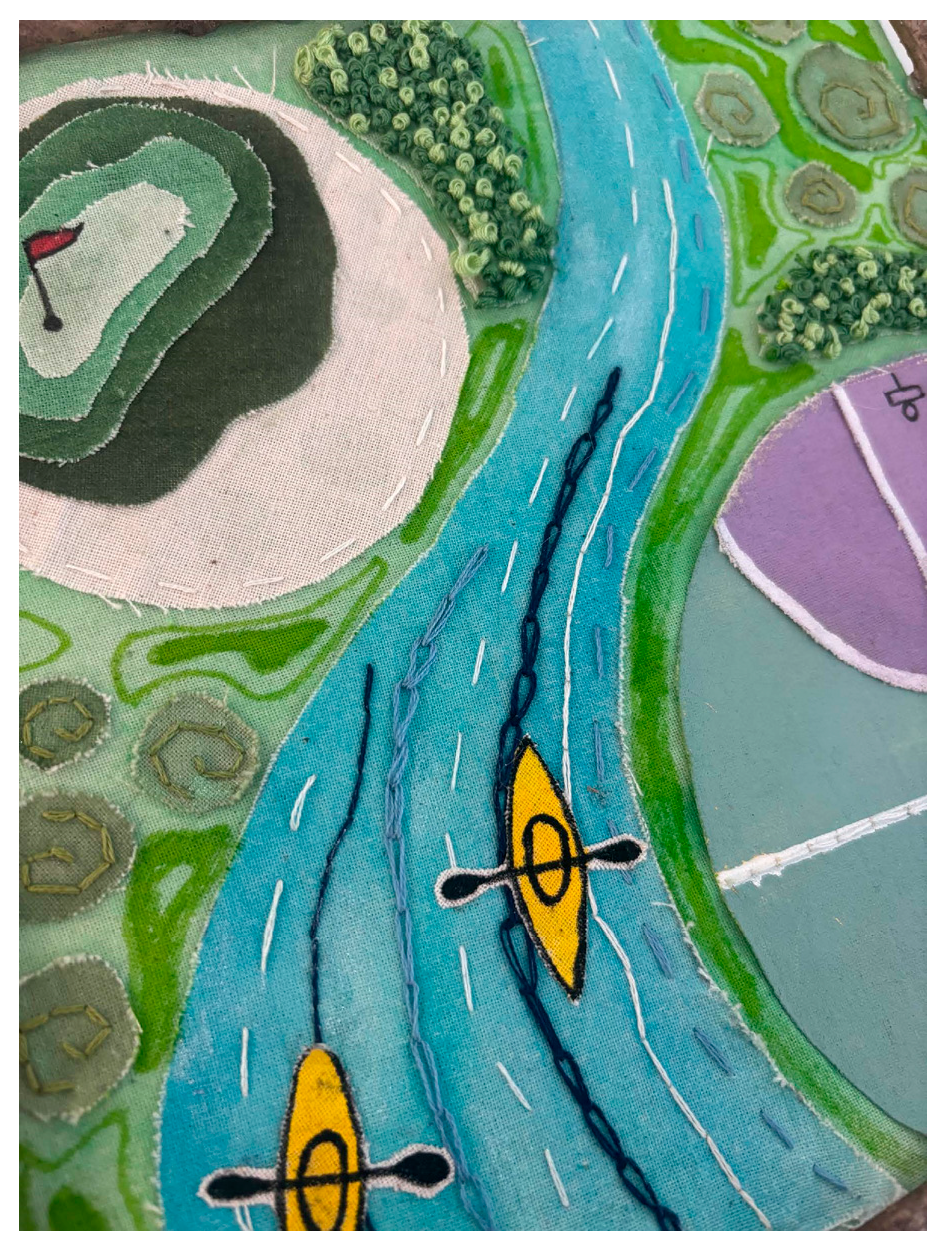

This paper argues that applying 15-minute city principles to university campuses can fundamentally enhance biodiversity, health, and wellbeing. Using co-design research from Birmingham City University (BCU) as a foundation, we demonstrate how regenerative design can translate 15-minute city principles into tangible, co-created ideas for change (see

Figure 20). The proposals bring the four guiding principles of ecology, proximity, solidarity and participation into campus design through key ideas of the pedestrianized campus, inclusion of living infrastructure, study and break pods, market and community hubs, reconceptualizing the campus as a part of nature and redesign of the campus towards autonomy in relation to energy, water and even food, whilst connecting to wider systems.

By adopting this approach, universities have the potential to transform campuses into learning environments that act as lived ecosystems, changing the human–nature relationships on campus, and acting as autonomous nodal systems that are interconnected to wider ecosystems.

5.1. The 15-Minute Campus: A Living Ecosystem

Our research explores design implications of applying 15-minute city principles to a ‘real-world’ university campus. The resultant ‘15-minute campus’ emerges not merely as a collection of proximate amenities but as a living, evolving ecosystem that values community, biodiversity, and cultural heritage. A key insight from our participatory design process was the stakeholders eagerness to be co-creators of these futures. Their imaginative contributions, ranging from physical artifacts to symbolic models of interconnectedness, expressed a collective relationship for reconnection with place, nature, and each other. As climate and mental health crises converge, the university campus must evolve from a space of consumption to one of contribution. Through a 15 min design lens and a regenerative ethos, campuses can become models for how cities might flourish: slowly, locally, ecologically, and justly.

5.2. Reinterpreting the 15-Minute City: From Metrics to Lived Experience

This research contributes to the existing discourse on the 15-minute city by offering a critical interpretation within a university campus context. While existing 15-minute city research often prioritizes quantitative metrics—such as proximity to services or daily destinations—this study explores more qualitative, experiential approaches. The participatory design process placed significant value on lived experience, emotional connection, and multisensory engagement. This suggests that the success of a 15-minute campus cannot be fully understood through spatial efficiency or service access alone. Instead, its efficacy must be grounded in the wellbeing, identity, and ecological interdependence of its inhabitants.

5.3. Redefining Human–Nature Relationships on Campus

A pivotal epistemological shift emerged: from viewing nature as an esthetic or functional “add-on” to campus planning, to understanding both the campus and its inhabitants as fundamentally part of nature. This aligns with regenerative thinking, which resists the human–nature binary and instead embraces co-evolutionary relationships between human systems and the wider living world [

33]. The concept of the campus as a “clearing in the forest,” articulated by participants, reframes the university not as an enclave separated from nature, but as a dynamic participant in local ecologies. Proposed interventions, such as biodiversity corridors, living benches, and Miyawaki micro-forests, embed ecological processes directly into the physical and cultural life of the campus, fostering conditions for reciprocal flourishing.

5.4. Towards Autonomous and Interconnected Campus Systems

This research also extends the 15-minute city model by exploring the university campus as a partially autonomous unit—capable not only of service provision but also of self-sustaining functions such as food production, water harvesting, biodiversity regeneration, and renewable energy generation. The proposed living infrastructure, including solar-powered street furniture and rainwater-collecting microhabitats, points towards a future where campuses operate as regenerative engines within their urban contexts. This marks a significant move away from dependency on centralized urban systems and towards distributed, locally grounded infrastructures that enhance resilience and autonomy.

Moreover, these semi-autonomous campuses can be understood as forming part of a wider rhizomatic network—interconnected not by rigid hierarchies but through flexible, informal, and multidirectional linkages. The campus market, for example, transcends a purely economic space; it becomes a node of exchange across multiple systems—social, ecological, cultural, and economic—connecting local producers, students, and residents. In this way, the 15-minute campus is not an isolated enclave, but a living node within a decentralized network of regenerative urban micro-systems. This resonates with Deleuze and Guattari’s notions of rhizomatic structure, suggesting a model of urban futures built not on linear expansion but on interdependent, adaptive units of change [

50].

6. Conclusions

This research explores how the principles of 15-minute city concept model might be applied in a University campus setting. The research articulates a necessary and innovative reorientation of the 15-minute city—from a model concerned primarily with needs and efficiency, to one grounded in ecological consciousness, autonomy, and human–nature co-evolution. The research highlights the transformative potential of a regenerative 15-minute campus and points to three key themes: biodiversity, health, and wellbeing. By integrating living infrastructure, ecological corridors, and nature-based solutions, the campus becomes an active participant in urban biodiversity restoration—moving from fragmented green spaces to coherent, thriving habitats. In terms of health, the reimagined campus supports active, outdoor lifestyles through walkable green routes, accessible public spaces, and multifunctional infrastructure that encourages movement and play which aligns with previous quantitative research findings. It also demonstrates that applying the 15-minute city concept to university campuses can achieve multiple benefits, including active travel; more inclusive design; sustainability; biophilic design; wellbeing benefits; increased biodiversity; and health benefits—meaning that through the application of one model there are many advantages.

Significantly, this research positions wellbeing in the 15-minute campus as an emergent quality of ecological and social connection. Through participatory design, stakeholders contribute to shaping spaces that foster belonging, emotional attachment, and co-responsibility for place. In doing so, the 15-minute campus becomes more than an urban planning concept: it is a regenerative framework for reweaving relationships between people, place, and the living world. This research is one of the first to develop designs for a 15-minute University campus setting, but it highlights the need for further research to explore the participatory process of applying 15-minute city concepts in a wider range of contexts, climates and contexts.