1. Introduction

The floor area of buildings is expected to increase by 75 percent by 2050, 80 percent of which will be in developing countries [

1]. The significant rise in buildings and construction activities has brought enormous pressure and challenges to the environment and global economies, especially climate change issues [

2]. For example, the operations and materials used in buildings and construction account for approximately 34 per cent of global CO

2 emissions and 32 per cent of the final energy use [

3]. Over the past few decades, researchers, climate activists, and national governments have been finding novel ways to decarbonize the built environment sector to promote affordable housing supply towards sustainable urbanization [

4]. One such approach is green building (GB) [

5].

GB mitigates the negative impacts of buildings on the climate and natural environment throughout the lifecycle stages [

6]. For example, GB adopts ecologically sustainable principles from the substructure to the superstructure through decommissioning [

7]. With sustainable principles such as energy efficiency, GB can potentially reduce global CO

2 emissions by 43 percent by 2030 [

4]. It can also lower the operating cost of buildings, increase occupant comfort, health, and productivity, enhance corporate reputation, and increase the market value of buildings [

8]. Although GB has several benefits, its implementation remains minimal. It is faced with barriers such as higher (perceived or actual) investment costs, lack of government support or incentives, lack of market demand, lack of public awareness, and inadequate capital and green finance (GF) [

3]. GB and energy efficiency investments in buildings represent less than 4 percent (USD 237 billion) of the global buildings and construction sector value (USD 6.3 trillion) [

3]. The literature [

3,

9,

10] suggests that GF presents opportunities to close the GB investment gap.

GF refers to financial instruments supporting the climate-resilient transition through funding activities that protect the environment, such as emissions reductions, reduced energy use, and developing climate-resilient infrastructure [

11]. The International Finance Corporation [

12] estimates a GF-in-GB investment opportunity of USD 24.7 trillion in emerging economies by 2030. Although GF has received increased attention recently, some adoption and implementation barriers exist [

10,

13,

14]. Identifying and prioritizing the barriers to GF-in-GB would provide critical information to enable policymakers to reduce decision inefficiencies, enhance stakeholder acceptance and investment, and strategically develop novel GF-in-GB initiatives.

Few studies have been conducted on barriers to GF-in-GB using several methods and analytical tools. For example, Ref. [

15] identified the key barriers to accessing GF for building energy retrofits by energy service companies (ESCOs) in China. The key barrier identified was limited access to GF, preventing ESCOs from expanding in the country. Agyekum et al. [

13] examined professionals’ perceptions of the obstacles to GB project finance in Ghana’s construction sector. The significant challenges were split incentives, risk-related barriers, capital expenditure, lack of incentives, and initial capital cost. Survey methods and interviews were used in these studies. Ref. [

16] adopted a mix of surveys, focus groups, and interviews to assess the barriers to investment decisions for green infrastructure by large European insurance companies. According to the participants from the insurance sector, banks and development finance institutions, regulatory obstacles and a lack of bankable projects and project pipelines are the main barriers to green investment. The analytical tools employed in these studies included descriptive analysis, one-sample t-test, One-Way ANOVA, and content analysis [

13,

15,

16]. Although previous studies have demonstrated that some key barriers are responsible for the slow uptake of GF-in-GB, the interrelationships among the barriers identified were not considered.

It is argued in the literature that adoption and implementation barriers have some interdependencies among them and that one barrier can stimulate the occurrence of other barriers [

17,

18,

19]. In addition, surveys adopted in previous studies may be prone to subjectivities and ambiguities. In addition, these studies do not consider the existential relationships between the barriers identified. While these subjectivity gaps and challenges persist in survey-based studies, fuzzy approaches used in multicriteria decision-making methods, such as the decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) and Delphi methods, can address them [

20]. The DEMATEL method provides a more systematic and interactive research process of the judgment of a panel of independent experts on a particular issue [

21]. In addition, DEMATEL helps develop mutual relationships of criteria and their correlated mutual relationships and influences of the criteria. This method can analyze total relations and provide a causal-effect diagram to describe the logical and mutual relationships, direct impacts and influences among sets of variables [

18,

22]. Researchers have adopted the fuzzy set theory to handle uncertainties in the DEMATEL method [

23]. Linguistic preference scales used in DEMATEL studies allow experts to easily convert qualitative information into fuzzy numbers. The fuzzy logic is necessary for handling such vagueness and imprecision in human judgment [

23]. Hence, there is a need to extend the DEMATEL method with fuzzy logic to make better decisions in fuzzy environments [

17,

18,

19]. Hence, the fuzzy DEMATEL (FDEMATEL) was adopted in this study. Before applying the FDEMATEL, the fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM), which integrates the fuzzy set theory into the classical Delphi procedure, was used to validate identified factors from the literature [

24].

As explained above, the previous studies based on single surveys, interviews or focus groups do not consider the influences and relationships between the barriers of GF-in-GB under fuzzy environments. To address these gaps, this study aims to quantitatively and objectively assess the interactions between the barriers to GF-in-GB using the two-step fuzzy Delphi–DEMATEL. This study is important first because, given the few studies examining GF-in-GB in developing economies, its empirical findings add significantly to the existing GF-in-GB literature. Moreover, this study would be critical to understanding the most important and critical barriers and their cause-and-effect interrelationships. Knowledge of these relationships would be useful to industry practitioners, the government, decision-makers, and other stakeholders in sustainably focusing the limited resources on addressing the influential and critical barriers. Furthermore, this study can be an important reference point for policymakers and advocates interested in promoting GF-in-GB in Ghana and other emerging economies to achieve more sustainable economies and societies.

3. Literature Review of Barriers to GF-in-GB

GF-in-GB models and their implementation differ among economies [

41]. As noted, different barriers hinder successful implementation across regions, countries, and even cities. All specific finance-related barriers to GB implementation in Ghana identified in the literature were considered in identifying barriers to GF-in-GB. It is preferable to employ well-known factors in a research study so that respondents can respond efficiently [

42]. As such, various barriers to GF in the literature were comprehensively reviewed. Relevant papers were retrieved from Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar using “barriers”, “green finance”, and “green building” keywords and their variants. The search returned 27 articles discussing the barriers of GF-in-GB. The screening criteria for identifying relevant literature were studies examining GF in sustainable buildings and construction. After thoroughly examining these articles, five barriers to GF-in-GB with 22 indicators were shortlisted (see

Table A1,

Appendix A). This barrier categorization was based on similar groupings in the literature [

43,

44,

45]. In addition, two experts with at least ten years of industry and/or academic experience were consulted during the shortlisting of the barriers and the groupings. A summary of the identified barriers is provided below:

3.1. Financial Barriers

Financial barriers relate to when high costs make certain activities problematic to afford [

46] (i.e., all cost-related GF barriers). Following the literature review, six financial barriers to GF-in-GB were identified: split incentives, short-termism, limited GF supply, capital adequacy and liquidity issues, costly processes, and economic instability. The main challenge of GF is that of incentives [

47]. According to Ref. [

48], there is a perception of the uncertain benefits of green bond issuances. For instance, split incentives were identified as a significant barrier to GF in building energy efficiency retrofits in China [

15]. Similarly, Ref. [

13] found split incentives to be a significant barrier to financing GBs in Ghana. This lack of incentive for GF or to structure green bonds originates from the certification process [

49] and its inability to show tangible benefits [

50]. A survey revealed that the potential mismatch between investor and issuer expectations poses pricing uncertainty in the Ghanaian market [

41]. Maturity mismatches or short-termism remain a critical issue in the global development of GF [

51,

52]. Again, the underlying liquidity profile of potential GF product issuers is crucial.

Similarly, SMEs lack capital requirements for GF, leading to inadequate financing schemes [

13]. Owing to the insufficient capacity of SMEs to develop qualified funding proposals that meet requirements [

15], green banks are reluctant to support green projects. In addition, the collateral obligations of SMEs are incredibly high and rigorous [

15,

53]. For example, it is reported that SMEs require as much as 120% collateral from the total loans obtained and to have a creditworthy sponsor [

53]. Usually, a minimum project finance size of at least USD 100 million is also necessary [

54], making it more challenging for SMEs to access GF. Other stakeholders perceive GF as a costly process, with higher transaction costs or additional fees [

15,

48,

49]. The high up-front costs related to the perceived high cost of low-carbon technology investments remain critical [

47,

49]. In addition, poor economic conditions, notably exchange rate volatility and rising inflation, may dissipate interest in GF [

13].

3.2. Regulatory Barriers

Regulatory barriers include international, national, state, or local laws, regulations, policies, and structures that may restrict the growth and development of GF. The three major regulatory barriers that affect GF-in-GB are policy and regulatory uncertainty, political instability, and regulatory requirements. The literature shows that policy uncertainty is the biggest concern for investors [

54]. After three years, the government of Ghana has yet to implement its 2021 announcement of issuing a green bond [

41]. These failed promises do not signal how and to what extent the government intends to support and promote the green transition. Such uncertainties could inhibit private-sector participation in the GF market. In contrast, the Nigerian government created the Green Bond Guidance, leading to its first green bond issued in 2017 [

55]. Similarly, the Hong Kong government is famous for its sovereign green bonds in GBs [

56]. These government signals have enhanced private investor confidence and interest in GF.

Again, a stable political climate is critical for investors’ interest in a specific market. An erratic political atmosphere exposes the financial system to vulnerabilities, given the uncertainties in government policies [

57]. Regulatory requirements may lead to regulatory risks that can inhibit GF-in-GB growth. This results in cost increases for project developers regarding the time required to understand the new regulations and additional related costs [

58]. For instance, Ref. [

53] claims that current regulatory frameworks have limited effectiveness in providing a clear direction for financial institutions to develop sustainable finance action plans capable of mainstreaming it within their business practice. A survey of professionals in Ghana revealed that the lack of guidelines for green bond issuance is responsible for the lack of clarity that market participants experience [

41].

3.3. Organizational Barriers

The context in which organizations operate can drive or frustrate development [

59]. The identified organizational barriers include greenwashing, inadequate management support, and inadequate private investment. The risk of greenwashing, also known as reputational risk, has been identified in the literature as a key GF barrier and remains a severe risk to all stakeholders [

48]. Greenwashing is the issuance of so-called green securities that lack environmental benefits. This emanates from the lack of a clear GF definition, leaving room for misleading claims about green projects [

60]. Emerging stories indicate that most GF is issued on greenwashing, a false representation that does not positively impact the environment [

55]. Again, the failure of top and middle management to embrace GF in operational activities and an unsupportive organizational structure for green transition impede the growth of GF [

10]. Additionally, insufficient private effort was identified in the literature review as a GF barrier. For instance, most renewable energy retailers in New South Wales are semi-privatized and barred from effectively entering into long-term public–private agreements [

61]. Dmuchowski et al. [

45] indicate a low private sector participation in financing a green economy in Poland. Therefore, private sector efforts in GF are very low and insufficient to meet the growing global need. However, to achieve meaningful, sustainable development, there is a need to leverage private sector investments with the current public spending on GF [

62].

3.4. Technical Barriers

The lack of knowledge and technical capacity or expertise of project developers, issuers, and investors has been identified in the literature as a barrier to GF [

15,

52]. While many experts lack knowledge regarding financial policies or tools for green projects [

47], companies often lack the financial management and accounting capacities required for a comprehensive green loan application [

15]. Ref. [

41] notes the importance of greater technical capacity in the Ghanaian market in enhancing GF. Lack of knowledge about GF is also influenced by inadequate research and development (R&D) support for GF-in-GB [

63,

64]. In addition, the perceived technology risk associated with uncertain GB technologies and products influences GF [

13,

41,

65].

3.5. Structural Barriers

Structural (or market) barriers are natural or strategic barriers that arise in the market to prevent new entrants. These barriers, either short- or long-term, collectively prevent GF products from gaining traction in the capital market. They include limited green projects, a lack of harmonized global standards and guidelines, risk perception, a lack of a universal definition for “green projects”, inadequate transparency and consistency with GF, information asymmetry, and a lack of quality historical data.

So far, few market participants can identify a pipeline of eligible green projects for GF because of the novelty of the product. Despite the rising interest in potential issuers in GF, there is a lack of eligible pipelines [

41,

48]. Mielke [

16] agrees that the lack of bankable projects and project pipelines is a major barrier to GF. Although the Government of Ghana has introduced several initiatives to support its transition to a green economy, GF remains nascent in the country, primarily due to the almost non-existent GBs in Ghana. While there is significant awareness of GF, few market participants have some level of understanding of GF across issuers and investors alike [

41]. There is also a lack of existing guidelines and regulations regarding GF. Ref. [

41] asserts that a functioning debt capital market is key to GF issuance. Hence, there must be appropriate legislative protection for investors showing a degree of transparency and good governance through credit ratings, market liquidity, and acceptable yields. Ref. [

55] argues that the lack of a harmonized system affects GF. This further deepens the challenges posed by the lack of credible historical information or databases on green projects and the various risk perceptions associated with green projects [

13]. Similarly, GF is plagued with imperfect information, where parties to a transaction have access to different levels of information [

66,

67]. Finally, the poor clarity on what can be classified as GF is a barrier to the demand for GF-in-GB [

10]. This unending debate on what qualifies as “green” in project financing is a big challenge to GF stakeholders [

68].

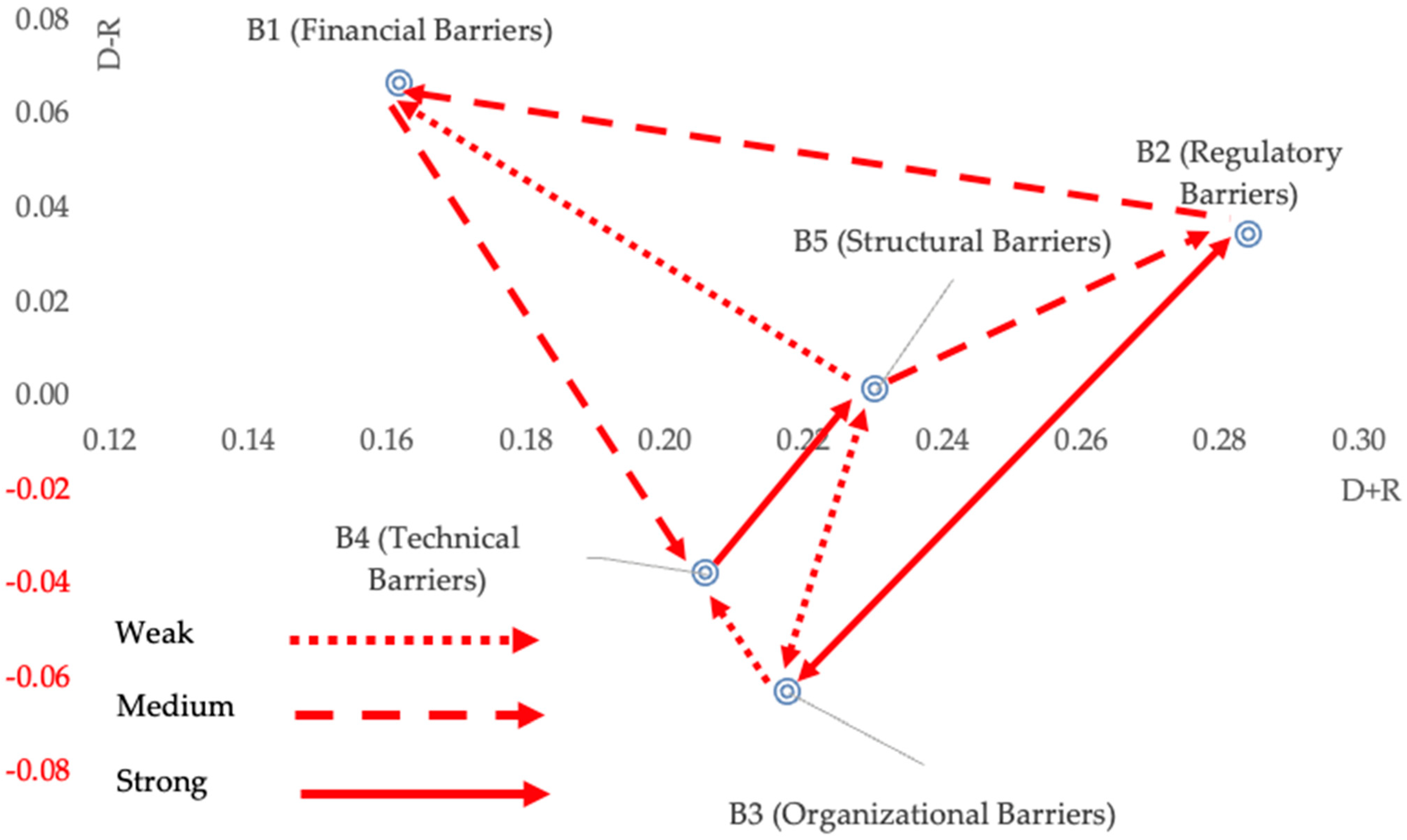

As presented in

Table A1 (

Appendix A) and explained above, 22 barriers to GF-in-GB in Ghana were identified and grouped into five categories. From the above literature review, several barriers hinder the adoption and implementation of GF. The few available studies on GB focus on Ghana, Europe, and China [

13,

15,

16]. To complement these studies, some general barriers to GF were also reviewed. While these studies provide significant findings, the interrelationships among the barriers are not considered. To overcome these gaps, a holistic approach that considers barrier interactions is suggested to be more effective than a unilateral approach [

17,

18]. Hence, this study aims to assess the interactions between barriers to GF-in-GB in Ghana through expert knowledge using the fuzzy Delphi–DEMATEL approach. The FDM was applied to validate the GF-in-GB barriers and indicators. Recent literature favors the FDM due to its simplicity and effectiveness, mainly because it requires a single investigation and does not mandate modification of expert opinions [

18,

24]. Based on the identified gap of the lack of interrelationships between existing barriers, the two-step fuzzy DEMATEL method employed in this study is explained below.

4. Research Methodology

This study used FDM and FDEMATEL survey methods to collect expert views on barriers to GF-in-GB. The FDM and FDEMATEL methodologies are emerging in sustainability-related research [

18,

69] and have recently been applied in GF-in-GB research [

20] in a related paper as part of a PhD study. This study proposes a three-phase method, as shown in

Figure 1.

First, barriers to GF-in-GB were extracted from an extensive literature review. Then, an interview was conducted with two experts with at least ten years of industry and/or academic experience in GB finance. This was intended to refine the barriers regarding their clarity, relevance, practicality, and validity in the study context [

24]. Secondly, the FDM was employed to select the critical barriers based on the case of Ghana. The FDM approach presented here was structurally designed to assess the list of pre-screened barriers extracted from the literature review and through the expert panel interview. Finally, the cause–effect interrelationship of the barriers was obtained by using the FDEMATEL.

Research has shown that the accuracy and effectiveness of the Delphi studies do not depend on the number of panelists alone, but on the qualities of experts [

21,

70]. Hence, the expert selection process was based on Ref. [

71]’s approach. They include experience and knowledge of the issues under investigation, willingness and capacity to participate, sufficient time to participate, and effective communication skills. The literature recommends a sample size of eight to 16 panelists for a Delphi panel [

21,

70]. In this study, 30 panelists from Ghana with an average of five years of experience in either GF and/or GB projects were contacted. Twelve valid expert opinions were obtained. Online and face-to-face methods were used in the data collection process. The relatively large Delphi sample of expert panelists considered issues such as some panelists dropping out due to other commitments or disinterest [

21]. The professional backgrounds of the respondents included Project/Construction Managers, Quantity Surveyors, Engineers, and Finance Experts. It should be noted that some respondents had multiple professional backgrounds. While the study was based in Ghana, some experts had international experience in countries such as the US, Australia, Hong Kong, Kenya, and Nigeria.

Table 1 summarizes the profile of the experts involved in this study.

The FDM and FDEMATEL methods employed in this study are explained below.

4.1. Fuzzy Set Theory

Human judgments are not definitive and are usually considered vague. Expressions like “very low,” “a bit better,” and “very likely” are common in daily conversations, leading to fuzziness, uncertainties, and ambiguities in expert judgment [

72]. The fuzzy set theory introduced by Zadeh [

23] uses linguistic variables to address such uncertainties and ambiguities. The fuzzy set theory employs fuzzy numbers, a fuzzy subset of real numbers, based on confidence intervals. Linguistic variables are words or sentences in a natural language for which no specific value exists [

73]. Linguistic variables, like “very likely” or “not likely”, can be indicated by a triangular fuzzy number (TFN) within a defined scale, like 0–10. A TFN is a fuzzy set with three membership functions or parameters: l, m, u. While the parameters l and u represent the lower and upper limits of a TFN, m denotes the center of the fuzzy number. This implies that a fuzzy number is approximately “m” and cannot be less than “l” or greater than “u” [

24,

72]. TFNs are easily understandable and, hence, are preferred by decision-makers. For instance, the linguistic variable “not likely” can be represented as a TFN (say 1, 2, 3), where a higher number means more likelihood.

4.2. Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM)

The FDM is an improved and modified version of the traditional Delphi method, which is useful in obtaining consensus among a group of experts through multiple rounds of surveys [

74]. While the FDM preserves the benefits of the conventional Delphi method, such as consensus building, it addresses other disadvantages, such as low convergence of experts’ opinions, high execution costs due to multiple rounds, and the possibility of filtering out particular experts’ opinions [

24]. Compared to classical Delphi surveys, FDM is advantageous for its “simplicity” and “efficiency.” In addition, FDM requires a single investigation and does not require experts to modify their extreme opinions [

24]. It also helps experts clarify their optimistic, pessimistic, and realistic opinions based on TFNs. Generally, the FDM is considered a systematic, interactive and predictive process where experts express their opinions using only one linguistic variable [

24,

75]. The FDM process adapted from Refs. [

18,

24] is detailed below:

- Step 1:

Gathering experts’ opinions through questionnaire surveys:

A group of 12 GF-in-GB experts in Ghana was invited to organize and determine the direct interactions between pairwise barriers. The experts used the linguistic operators in

Table 2 to evaluate the interactions between each pair of barriers using one of five lingual expression hierarchies: extreme, demonstrated, strong, moderate, and equal.

The primary data collection instrument was a structured matrix questionnaire. Since Ghana has no experience in GF-in-GB and no open data on the interactions between the barriers, expert knowledge, which is more useful in such circumstances, is utilized. Although more experts were anticipated, few were found because of the novelty of the subject in the country.

- Step 2:

Aggregation and defuzzification of experts’ opinions:

The following procedures were used for aggregation and defuzzification. The geometric mean was used to aggregate the respondent scores, and the fuzzy weight

of each criterion was determined.

where

represents the significance evaluation score of the indicator

,

represents the expert-rated criterion

,

n represents the number of experts and

and

represent the lower, middle, and upper values of the TFNs, respectively. Additionally,

represents the number of indicators/barriers. The aggregated weights of each criterion are defined as follows:

The threshold

was chosen to screen out non-significant barriers/indicators: if

, then the

barrier is accepted; otherwise, if

, the

barrier is rejected.

The literature reveals four approaches to estimating the threshold values: strict, mean, moderate, and conservative. For more details, the reader is referred to Ref. [

76]. Similar to related studies [

18,

24], this study used the consensus among experts to set the threshold value at the average of TFNs.

4.3. Fuzzy Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (FDEMATEL)

In the second phase of the Delphi survey with the same experts, the FDEMATEL method was used to evaluate the cause-and-effect relationships among the barriers. While DEMATEL was employed to evaluate the causal-effect link between the barriers, the fuzzy set theory was utilized to resolve the fuzziness in expert judgements. Hence, the FDEMATEL can address such uncertainties and ambiguities during decision-making. In this study,

Table 3 was used to convert linguistic terms into equivalent TFNs after qualitative judgments were gathered.

For members in a decision group, denotes the fuzzy weight of the barrier impacting the barrier assessed by the evaluator.

The FDEMATEL approach implemented in this study is described in

Appendix B. The FDM and FDEMATEL analytical process, summarized below, was used to obtain the results [

18,

20]:

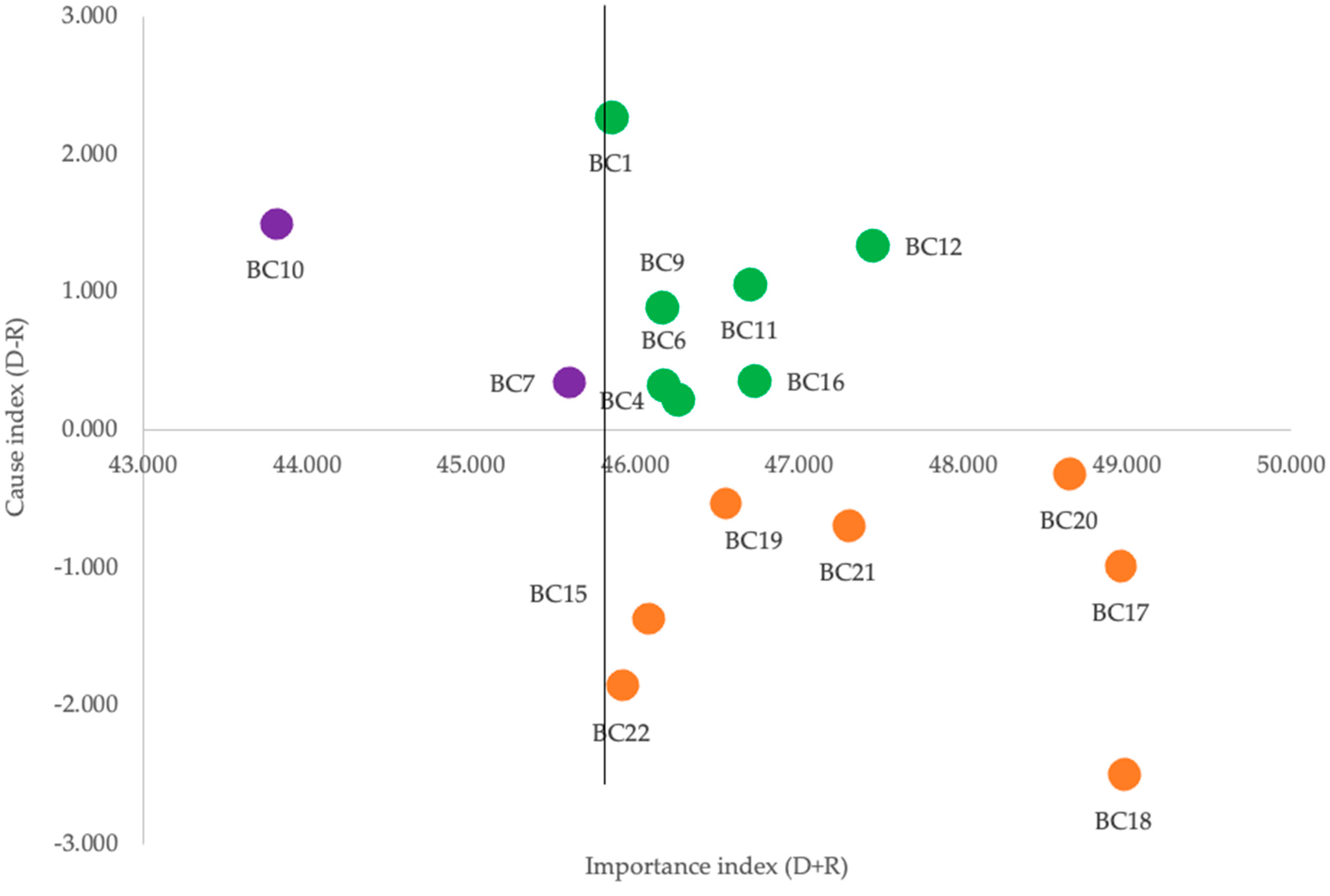

An initial set of 22 GF-in-GB barriers (

Table A1,

Appendix A) was identified from the literature and analyzed using FDM based on 12 experts from Ghana. Based on the FDM, Equations (1) and (2) were used to estimate the acceptable threshold at 0.525. Using the FDM threshold, non-critical barriers are removed.

Table A2 (

Appendix C) presents the FDM for the barrier weights and their thresholds.

Table 4 lists the 16 acceptable/critical barriers and aggregated fuzzy weights after deleting the defuzzied weights below the threshold.

Experts’ qualitative assessments were converted into equivalent TFNs (see

Table 3). Based on acceptable barriers or indicators, a new set of questions was examined using FDEMATEL. The same experts provided the data, and (Equation (A1),

Appendix B) was used to normalize the assessed TFNs. (Equations (A2)–(A4),

Appendix B) were used to determine the normalized values, total normalized crisp values, and crisp values for each expert.

The IDRM and normalized direct relationship matrix were generated using (Equations (A5) and (A6),

Appendix B). (Equation (A7),

Appendix B) was used to compute the influence or significance level of the complete interdependence matrix.

(Equations (A8) and (A9),

Appendix B) were used to calculate the horizontal axis

and vertical axis

. The driving barriers in the first quadrant have causal features and are of higher importance. If a barrier is in the second quadrant, it is a voluntary barrier with a causal function but lesser importance. The third quadrant is made up of less important and independent barriers. Core problems are those mapped into quadrant four, indicating higher importance. The core problems rely on the driving barriers in the first quadrant, are unable to be improved by themselves, and require addressing the root problems [

18]. The analytical steps proposed in this study are summarized in

Figure 1.