Exploring the Garden Design and Underlying Philosophy of Lion Grove as a Chan Garden During the Yuan Dynasty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. The Idea of Nature in Yuan Dynasty’s Lion Grove

There was a plot of land along the Eastern River in Suzhou, where the ancient trees, bamboo groves, and stones gave me a sense of being deep in the mountains. This environment was serene and captivating to me, so I purchased this land along with my disciples to construct Lion Grove.[15]

A clear pond occupies the front part of Lion Grove, while the back part features a small earthen mound with many uniquely shaped stones, beautiful bamboo groves, and various plants intertwining…… This garden is both a place for recreation and rest, making visitors feel as if they are in the mountains and forests, completely forgetting the close proximity to bustling Suzhou……The clear stream and artificial rockeries both reflect Chan’s principles and can inspire enlightenment.[19]

4. The Overall Landscape Planning Intentions of Lion Grove During the Yuan Dynasty

Lion Grove is the hermitage of Tianru Weize. After Weize completed his training under his master Zhongfeng Mingben 中峰明本, he lived in seclusion in the Nine Mountains in Songjiang, where he has resided for over a decade. In Suzhou, his disciples purchased a plot of land in the city, which had originally been a villa of the Song dynasty aristocracy. The site, densely forested, remained cool and refreshing even in the height of summer, resembling the tranquility of a remote mountain forest despite its location amidst the bustling city. As a result, Weize’s disciple decided to construct the Lion Grove on this land and invited Weize to reside there. Although there are not many buildings, is arranged within the serene natural landscape of the garden, featuring a Dharma hall, monk’s quarters, meditation rooms, and guest halls, all of which adhere to a certain order and structure. One prominent feature of the garden is a raised area surrounded by a collection of scenic rocks. Among these rocks, the tallest and most uniquely shaped, resembling a lion and centrally located, is called Lion Peak, while the rocks flanking it are named Hanhui Peak, Tuyue Peak, Liyu Peak, and Angxiao Peak. The remaining rocks are stacked together in various formations, rising and falling, resembling a group of lions. It is for this reason that the monastery was named ‘Lion Grove.’ The name also has its origins in Weize’s master Zhongfeng Mingben’s spiritual practice at Mount Tianmu, where there is a rock called ‘Lion Stone.’ To honor his master and the source of his own teachings, Weize named the garden ‘Lion Grove’ in memory of Zhongfeng Mingben. In front of Liyu Peak stands the Qifeng Pavilion, which contains stone benches that can accommodate six to seven people. A bridge, known as Xiaofeihong Stone Bridge, spans a small stream within the garden. More than ten thousand bamboo plants surround the pavilion on three sides. The plaque ‘Bodhi Lan Ruo 菩提蘭若,’ written by Shiyan Gong 石巖公 from Gaochang, is displayed on the pavilion’s door, serving as a symbol of wisdom and spiritual practice. The garden also features two notable trees, a cypress called the ‘Jiaolong 蛟龍’ (Flood Dragon) and a plum tree referred to as the ‘Wolong 臥龍’ (Crouching Dragon), both of which lend their names to two pavilions: Zhibai Pavilion and Wenmei Pavilion. These names are inspired by Chan stories from Master Mazu 馬祖 and Master Zhaozhou 趙州, used to teach the monks who come to study the teachings of Chan. The garden includes two water features, Binghu Well 冰壺井 and Yujian Pond 玉鑑池, which metaphorically represent the Buddha-nature through the element of water. Behind Lion Peak is a small hut made of thatch, where Weize meditates. The hut’s doorframe bears a plaque inscribed with the words ‘Chan Wo.’ Inside Chan Wo are eight mirrors arranged in a circular formation, reflecting each other and symbolizing the interplay of Buddha-nature and human nature in Chan meditation. This arrangement encourages meditation practitioners to attain insight and awareness.

5. The Designer of the Main Elements in the Garden

During the Yuan Dynasty, two individuals, Feng Haili and Ni Yunlin, played key roles in the development of Lion Grove. They were responsible for laying tiles in the buildings, designing and stacking the rock formations, as well as managing the ponds and maintaining the overgrown grass during the garden’s construction.

6. The Name of Garden Elements and the Literature

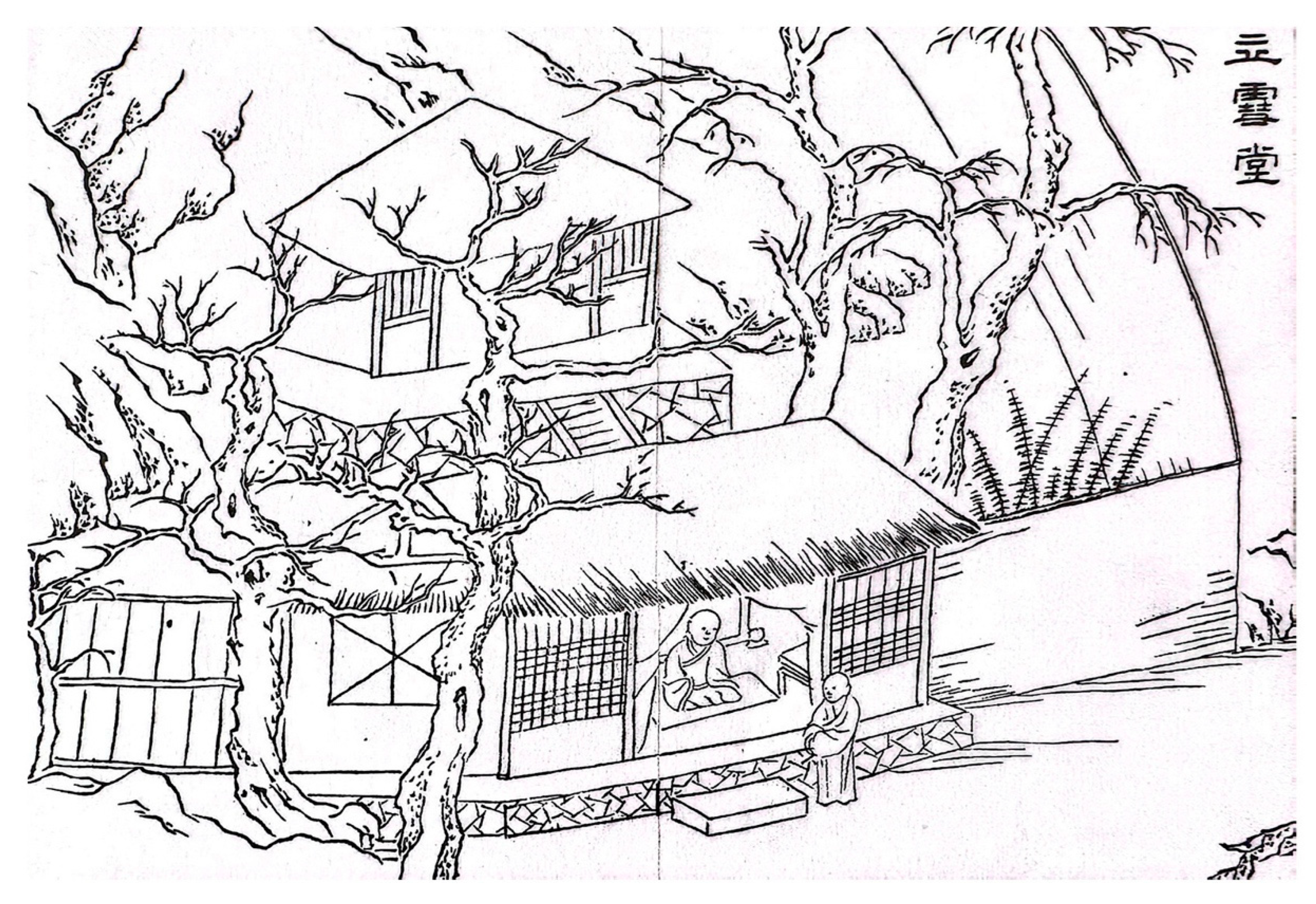

6.1. Lixue Hall (立雪堂: Hall of Standing in the Snow)

- 問法身忘倦,

- Questioning the Dharma body tirelessly,

- 堂前積雪深;

- snow piles up deep in front of the hall;

- 飛花知落去,

- The falling petals know their destination,

- 弟子已安心。

- while the disciple has already found peace.

6.2. Zhibai Pavilion (指柏軒: Pavilion of Pointing at the Cypress Tree)

- 去衲露玄机,

- Shedding the monk’s robe reveals profound mysteries,

- 非言亦非默;

- neither in words nor in silence;

- 西来意若何,

- What is the meaning of coming from the West?

- 笑指庭前柏。

- A smile points to the cypress in the garden.

One day, a disciple of Zhaozhou asked him: ‘What is the Buddha Dharma that Bodhidharma brought from the West to the land in the East (China)?’ Zhaozhou pointed at a cypress tree in the garden and replied: ‘It’s this cypress tree.’ The disciple questioned again: ‘You shouldn’t answer me in this way. What exactly is the Buddha Dharma brought by Bodhidharma?’ Zhaozhou replied persistently: ‘It’s that cypress tree.’

6.3. Wenmei Pavilion (問梅閣: Pavilion of Consulting the Plum Tree)

- 問梅之閣,蓋取媽祖……機緣,以示其來學。

- The name of Wenmei Pavilion originates from the Gongan story of Chan master Mazu, which is used to instruct those who come for Chan meditation.

When Fachang (Mazu’s disciple) first met Mazu, he asked, ‘What is enlightenment?’ Mazu replied, ‘The mind is enlightenment.’ After hearing this, Fachang became enlightened and later became the abbot of Dameishan Temple.

Later, Mazu sent one of his assistants to visit Fachang at Dameishan Temple and said to Fachang, ‘Mazu’s doctrine has changed, and enlightenment is now seen as neither the mind nor the Buddha.’

Fachang said, ‘Mazu, the old man, confuses people. Regardless of whether his doctrine changes or not, I still stick to my belief that the mind is enlightenment.’ The assistant went back and told Mazu about his conversation with Fachang, and Mazu said with satisfaction, ‘The plum is ripe.’

6.4. Woyun Chamber (臥雲室: Chamber of Lying in the Clouds)

- 臥雲室冷睡魔醒,

- I awaken from the icy slumber in the Woyun Chamber,

- 殘漏聲聲促五更;

- The sound of raindrops hastening the arrival of dawn;

- 一夢又如過一世,

- A dream feels like a lifetime has passed,

- 東方日出是來生。

- The sunrise in the East heralding rebirth into Nirvana.

- 盤盤範家筆,老懷寄高蹇。

- The ink paintings by the Fan, reminiscent of winding mountain paths, embody the lofty aspirations of the elderly artist.

- 嵩丘動歸興,突兀青在眼。

- The scenery of Songshan Mountain evokes his yearning for reclusion, with the imposing green mountains seemingly within reach.

- 何時臥雲身,因節隧疏懶。

- When will I, like Fan, lie among the clouds, build a thatched hut, and lead a leisurely and carefree life?

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J. Comparative Study on Lion Grove and Saihoji Temple—Linji. Zen Garden at the End of Yuan Dynasty. Master’s Thesis, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China, 2022. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD202301&filename=1022711095.nh (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Tian, Y.; Fang, H. Research on the historic appearance of the Lion Grove from the Yuan dynasty to the Republic of China. Stud. Hist. Gard. Des. Landsc. 2017, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. A Preliminary Study on Suzhou Lion Grove Realm Zen Creating Skill. Master’s Thesis, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China, 2016. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201701&filename=1016253003.nh (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Zou, H. Between Dream and Shadow: The Aesthetic Change Embodied by the Garden of Lion Grove. Montr. Archit. Rev. 2018, 5, 5–19. Available online: https://mar.mcgill.ca/article/view/35 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Zou, H. From Zen to Labyrinthine Ecstasy: Historical and Aesthetic Exchanges Between Two Gardens of Lion Grove. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 29, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.L.; Luo, C.H.; Chen, X.J. The creation of complexity in Chinese garden. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 209, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Zhang, J.; Shen, F.; Zhao, C. The multi-tech protective monitoring of the Lion Forest Garden Stony Artificial Hills (Suzhou, China). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 44, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Making the Qianlong Emperor’s Private Garden: Imperialization of the Lion Grove in Eighteenth-Century China. Master’s Thesis, University of Ablerta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hua, W.; Xu, Y. “Seeing” or “Being Seen”: Research on the Sight Line Design in the Lion Grove Based on Visitor Temporal–Spatial Distribution and Space Syntax. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lian, Z.; Xu, Y. Combining GPS and space syntax analysis to improve understanding of visitor temporal–spatial behaviour: A case study of the Lion Grove in China. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamabe, N. Did Monks Practice Meditation in Indian Rock-Cut Monasteries? and If Affirmative, Where in the Monastery? Int. J. Buddh. Thought Cult. 2023, 33, 19–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Chan and Chinese Garden; The Commercial Press International Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, S.; Naka, T. Japanese Gardens: Symbolism and Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Commentary on Master Tianru’s Biography; Jiangxi People’s Publishing House: Nanchang, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Continuation of the Tripitaka, Volume 710. In Sayings of Master Tianru of Lion Grove; Thread-Binding Books Publishing House Press: Beijing, China, 2005; Volume 8, pp. 821–906.

- Weize’s poem Shizilin Jijing Shisi Shou. In Shizilin Jisheng Ji; Sitting up, I Carry a Long Rattan Cane, Wandering Through the Garden as if Patrolling the Dharma Hall; Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020.

- Weize’s poem Shizilin Jijing Shisi Shou. In Shizilin Jisheng Ji; The Half-Eaves Catch the Setting Sun, Drying Cold Clothes, a Bowl of Fragrant Soup with Wild Ferns, Rich and Hearty; Spring Rain and Spring Mist, Like a Few Children. On the Western Water Plains, Pine Trees are Being Planted, Returning Home; Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020.

- Weize’s poem Shizilin Jijing Shisi Shou. In Shizilin Jisheng Ji; As Night Deepens, the Disciples Begin Chanting Sutras. Moonlight Filters Through the Western Wall, Casting the Shadow of a Cypress Tree at a Slant. While Meditating, the Sound of the Well’s Pulley Suddenly Rings Out, I go to Fetch Water and Savor Tea Before the Rain; Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020.

- Qi, G. Poetry Preface Shizilin Shier Yong Xu. In Shizilin Jisheng Ji; Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M. Proofreading of Shizilin Jisheng Ji (Including Sequels); Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020; pp. 12–13, 64–65, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Weize. Shizilin Jijing Shisi Shou. In Shizilin Jisheng Ji; Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zongtai, G. Shizilin Fu. In Shizilin Jisheng Ji; Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jellicoe, G.; Jellicoe, S. The Landscape of Man: Shaping the Environment from Prehistory to the Present Day; Thames and Hudson: New York, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M. A Study on the Construction and Construction Intention of the Seclusion Garden in Japan, China and Korea. Ph.D. Dissertation, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z. Shizilin Wuyan Bayong. In Shizilin Jisheng Ji and Quan Yuan Shi; Lixue Tang, Yuan Dynasty; Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Shilin Bajing Bazhang Zhang Siju. In Shizilin Jisheng Ji; Ninth Tenth Line; Soochow University Press: Suzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Continuation of the Tripitaka Volume 118. In Sayings of Master Zhaozhou; Thread-Binding Books Publishing House Press: Beijing, China, 2005; Volume 13–14.

- Continuation of the Tripitaka Volume 119. In Sayings of Master Mazu Daoyi; Thread-Binding Books Publishing House Press: Beijing, China, 2005; Volume 1.

- Yuan, H. Ti Zhang Zuo Cheng Jia Fan Kuan QiuShan Hengfu. In Yi Shan Ji, 1st ed.; Li, X., Ed.; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1985; Volume 1, pp. 362–363. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, S. The Japanese Garden; Peter Lang Publishing: New York, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keswick, M.; Hardie, A. The Chinese Garden: History, Art, and Architecture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kuitert, W. Themes in the History of Japanese Garden Art; University of Hawai‘i Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, C.; Yi, Z. Chan Buddhism in Wilderness and the Buddhist Tourism. Cult. Relig. Stud. 2024, 12, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dynasty | Year | Event |

|---|---|---|

| Yuan | 1341 | Weize ended his 12-year seclusion and settled in Suzhou, residing in the original site area of Lion Grove. |

| 1342 | Weize and his disciples purchased the plot of land where he resided, officially establishing Lion Grove there in that year. | |

| 1350 | Weize Nirvana. | |

| 1352 | Lion Grove was renamed Bodhi Zhengzong Temple. | |

| Ming | 1368 | The jurisdiction of Lion Grove was transferred from Weize’s disciples to the abbot of Chengtian Nengren temple. |

| 1372 | Due to the turmoil of dynastic changes, Lion Grove has become desolate, but its buildings and garden remain intact. | |

| 1403–1424 | The buildings of Lion Grove had collapsed, the plants had decayed, and the pond had dried up, leaving only some rockeries. | |

| 1522–1566 | The garden area in Lion Grove was occupied by powerful aristocrats, while the remaining areas were taken up by ordinary citizens, leading to the separation of the temple area and the garden. | |

| 1589–1592 | Lion Grove was purchased by a monk named Ming Xing, and the buildings and gardens were rebuilt, named according to the names of various landscape elements during the Yuan Dynasty. | |

| Qing | 1648–1654 | A hermit named Chen Rixin added buildings to Lion Grove and donated Buddhist scriptures, which rejuvenated its popularity. |

| 1662–1722 | During this period, Lion Grove underwent several changes in ownership. Since then, no Buddhist monks have become the owners of Lion Grove, and it gradually transformed into a private garden. | |

| 1763– | Lion Grove was purchased by a scholar–bureaucrat named Huang Xuan and renamed She Garden. For the next 170 years, Lion Grove belonged to the Huang family. | |

| Republic of China | 1918 | Lion Grove was purchased by a wealthy merchant named Bei Renyuan, who restored the name of Lion Grove and renamed its landscape elements according to their Yuan Dynasty names. |

| 1941–1943 | Lion Grove was occupied by the Wang Jingwei government. | |

| The People’s Republic of China | 1953– | Lion Grove was nationalized and opened to the public. |

| 2000 | Lion Grove was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. |

| The Current Lion Grove | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scenic Spots | Implication | |

| 1 | ShuangXiangXian Hall (雙香仙館) | ‘Shuangxiang’ means ‘two fragrances’, and ‘Xian’ refers to deities or immortal beings in Taoism. This is a building for smelling fragrances of plum blossoms and lotus flowers here. |

| 2 | Zhen Qu Pavilion (真趣亭) | The Qianlong Emperor visited here, symbolizing his interest in pleasure. |

| 3 | Lotus Hall (荷花廳) | Used for appreciating the lotus flowers in the pond. |

| 4 | Zheng Qi Pavilion (正氣亭) | Used to commemorate Wen Tianxiang, a hero who resisted the Yuan Dynasty in the Song Dynasty, and to promote patriotism. |

| 5 | Yubei Pavilion (御碑亭) | To commemorate Emperor Qianlong. |

| 6 | Xiuzhu Pavilion(修竹閣) | A place that symbolizes the humility of bamboo and is used to appreciate bamboo, rocks, and water scenery. |

| 7 | Yan Yu Hall (燕譽堂) | The term ‘Yan Yu’ symbolizes a spirit that is not attached to material conditions but seeks happiness as the ultimate goal. |

| 8 | Xiaofang Hall (小方聽) | A place for qin (musical instrument), chess, calligraphy, and painting, symbolizing talent and entertainment. |

| 9 | Nine Lion Peak (九獅峰) | Nine replicas of the Lion Peak, each with a consistent meaning. |

| 10 | Ancient Five Pine Garden (古五松園) | Used to appreciate pine trees and commemorate the Qin Dynasty. |

| 11 | Ting Tao pavilion (聽濤亭) | ‘Ting Tao’ means listening to the sound of waves. This pavilion is used for viewing the artificial waterfall in the garden and appreciating its sound. |

| 12 | Hu Xin Pavilion (湖心亭) | Located in the center of the pond, it is used to appreciate the scenery of the pond and lotus flowers in different seasons. |

| 13 | Shan Pavilion (扇亭) | ‘Shan’ means banana leaf fan. This pavilion is used to commemorate the pure and unfettered mindset of Wen Tianxiang from the Song Dynasty. |

| 14 | Stone Boat (石舫) | Used for interacting with the waterscape and lotus flowers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, T.; Sun, M.; Goto, S. Exploring the Garden Design and Underlying Philosophy of Lion Grove as a Chan Garden During the Yuan Dynasty. Architecture 2025, 5, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030057

Liang T, Sun M, Goto S. Exploring the Garden Design and Underlying Philosophy of Lion Grove as a Chan Garden During the Yuan Dynasty. Architecture. 2025; 5(3):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030057

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Tiankai, Minkai Sun, and Seiko Goto. 2025. "Exploring the Garden Design and Underlying Philosophy of Lion Grove as a Chan Garden During the Yuan Dynasty" Architecture 5, no. 3: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030057

APA StyleLiang, T., Sun, M., & Goto, S. (2025). Exploring the Garden Design and Underlying Philosophy of Lion Grove as a Chan Garden During the Yuan Dynasty. Architecture, 5(3), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030057