Designing for Inclusion: A Comparative Analysis of Inclusive Campus Planning Across Australian Universities

Abstract

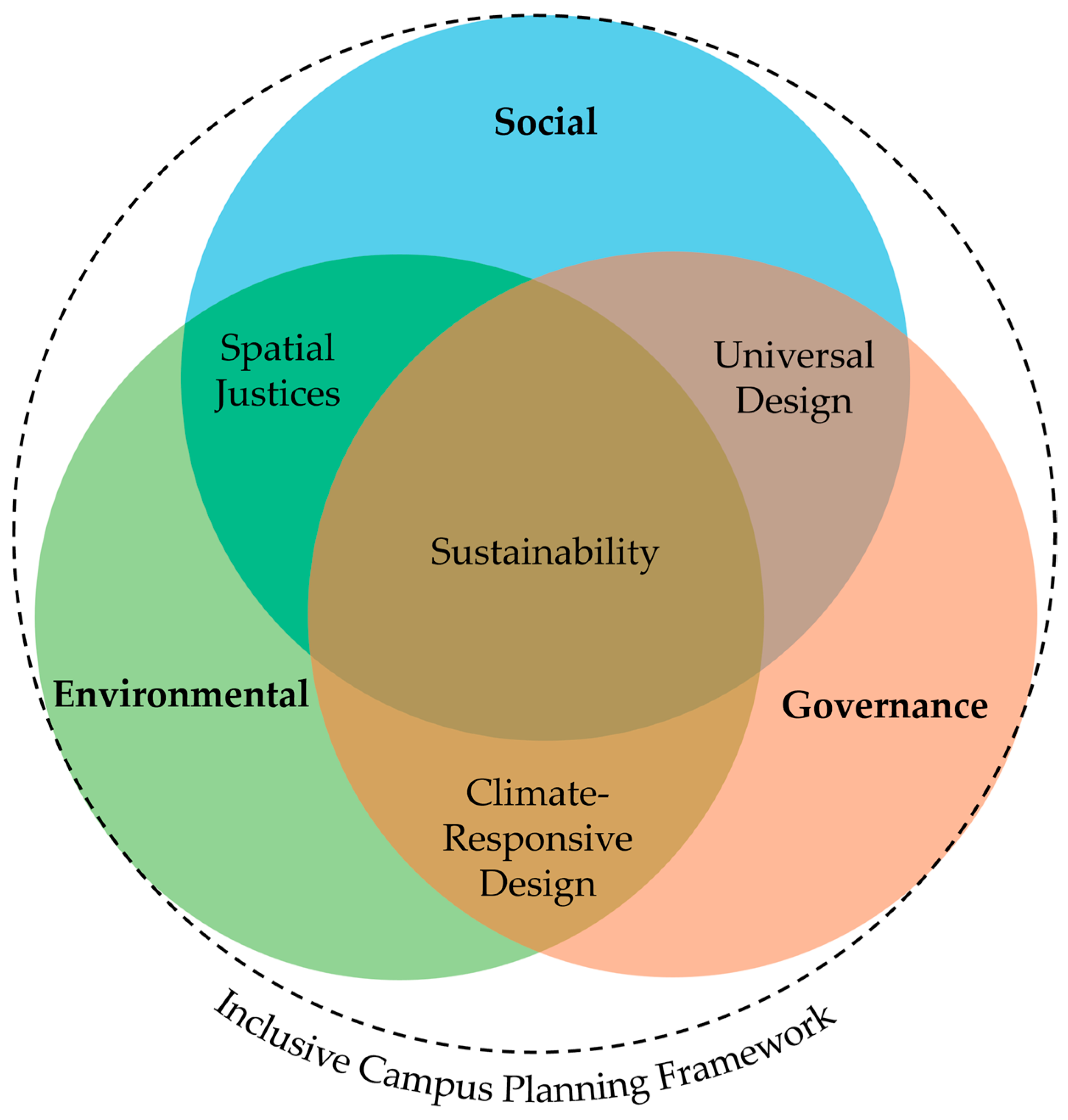

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

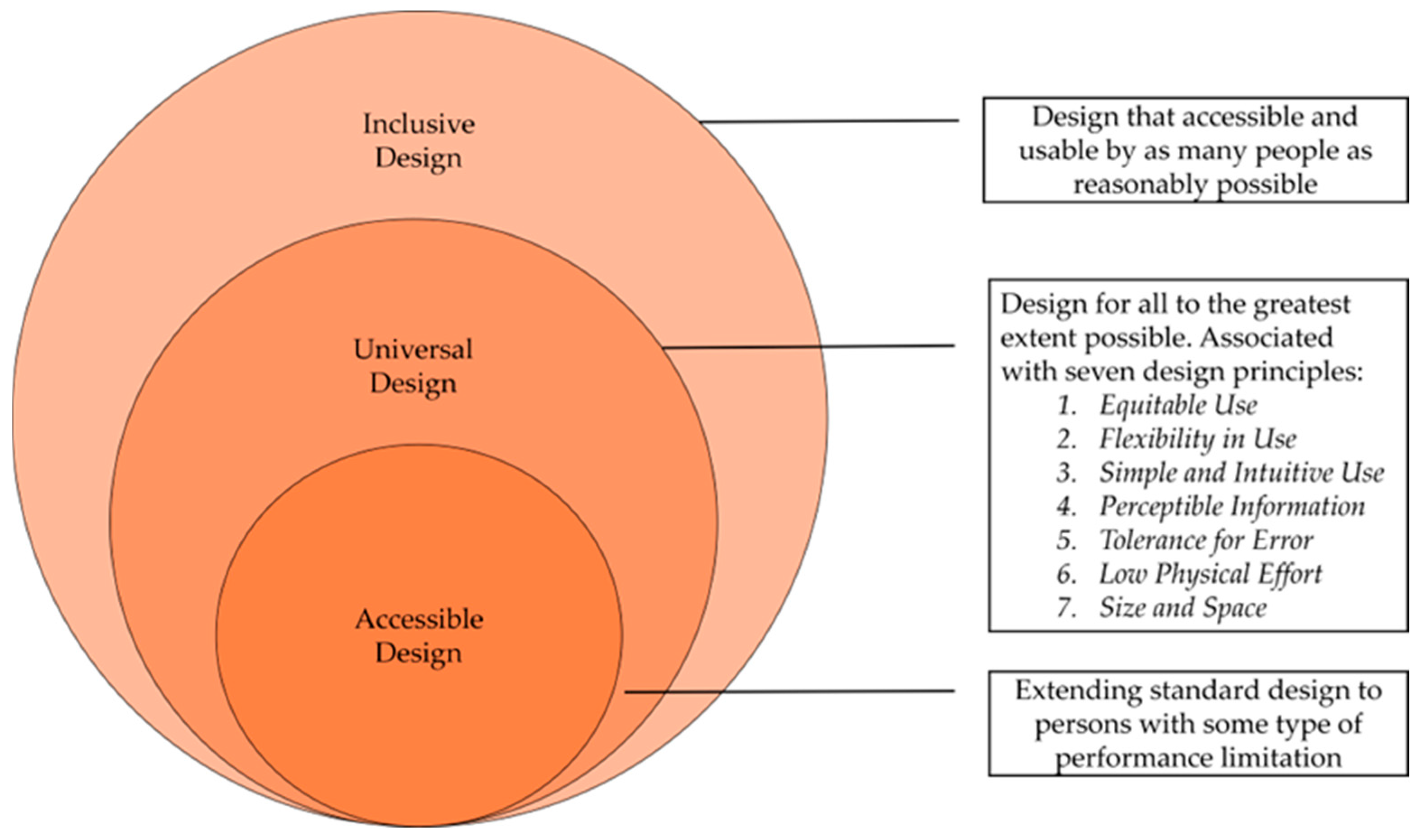

2.1. Evolving Definitions of Inclusive Campus Design

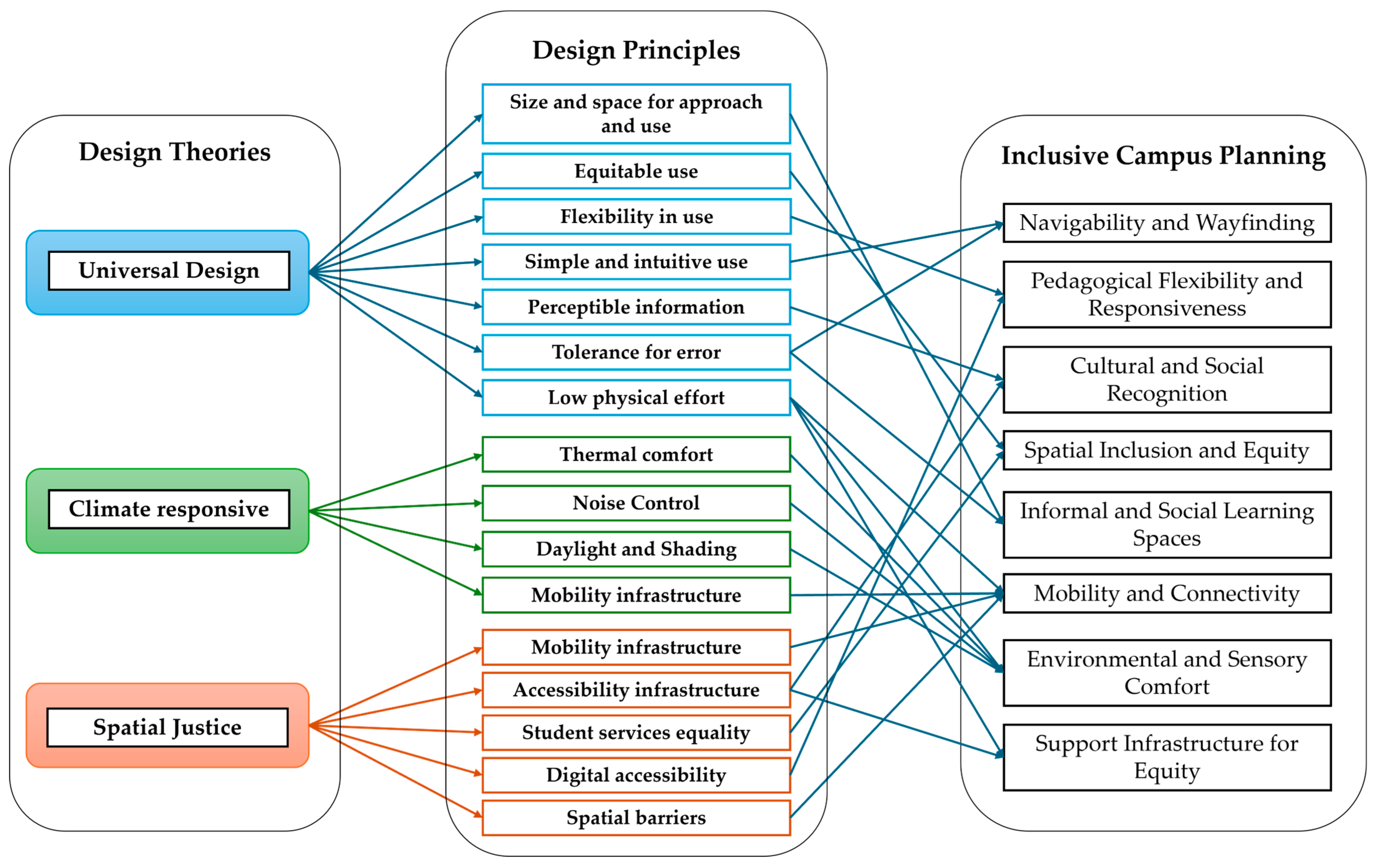

2.2. Universal Design in Higher Education

2.3. Spatial Justice and Campus Planning

2.4. Climate-Responsive Campus Design

2.5. Gaps in Current Research

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Deakin University

4.2. La Trobe University

4.3. Monash University

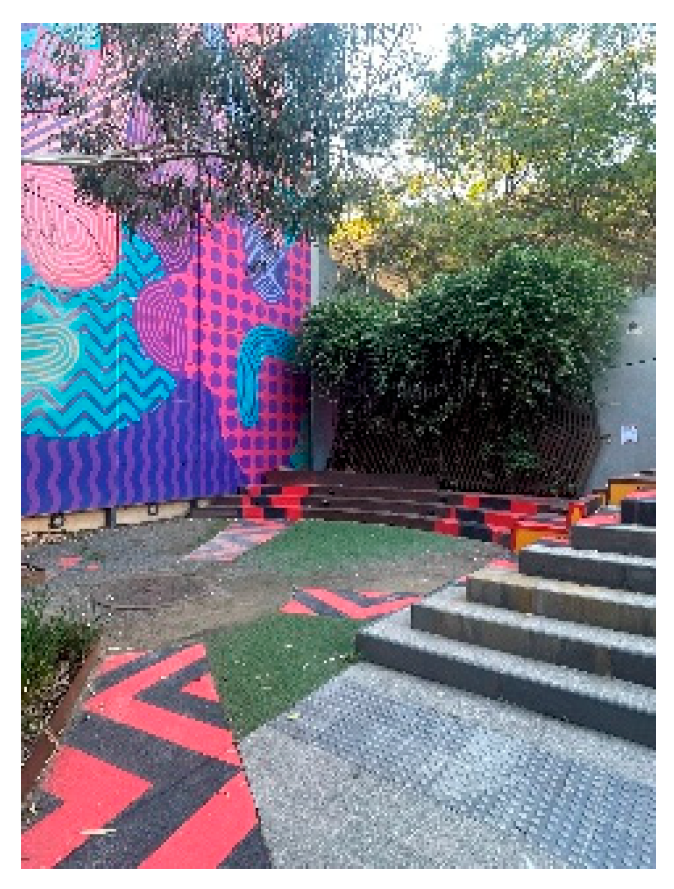

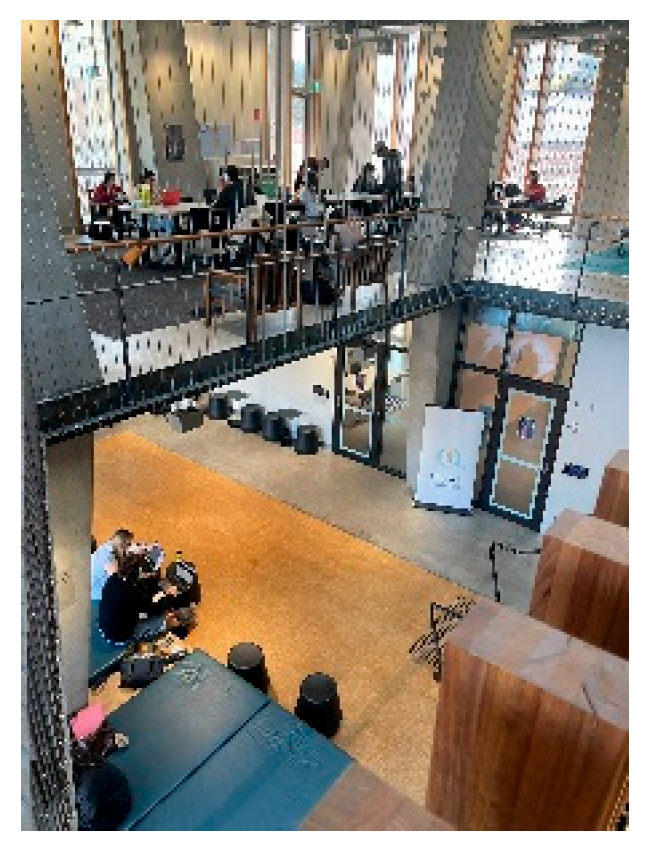

4.4. RMIT University

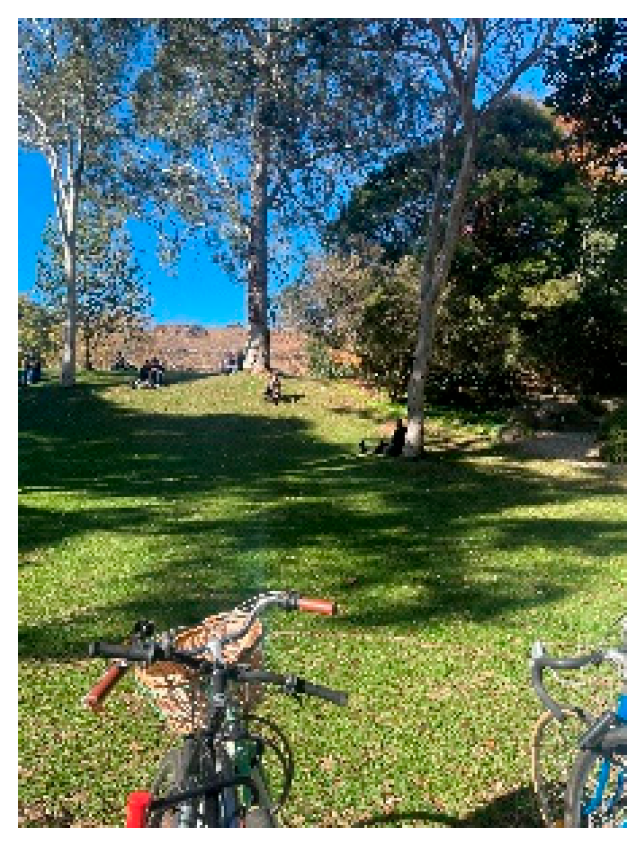

4.5. The University of Melbourne

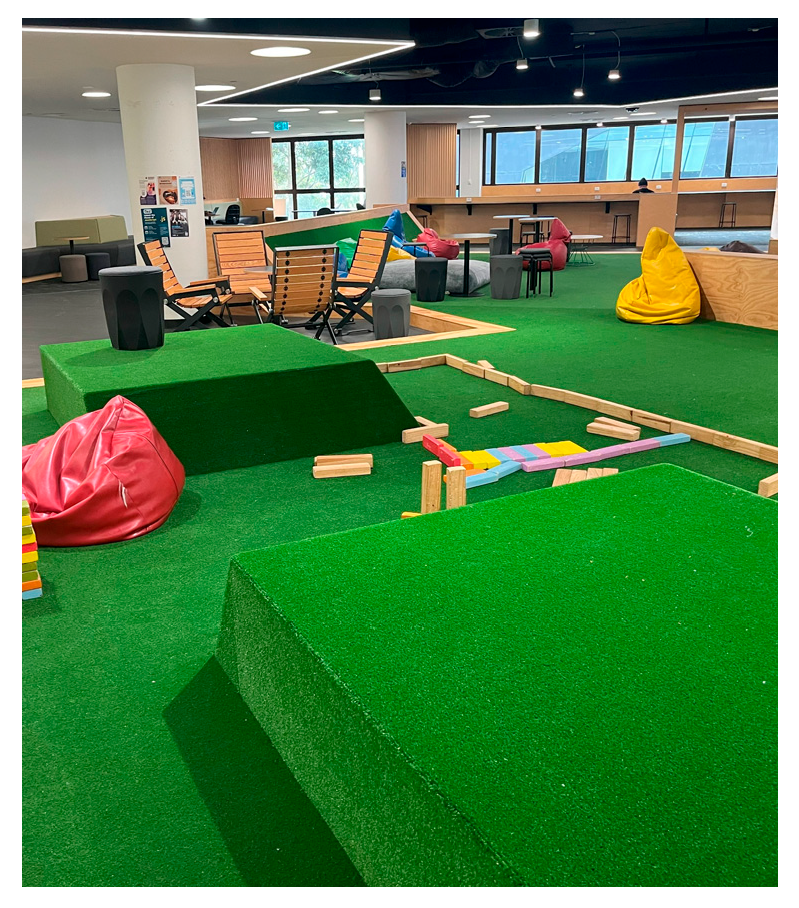

4.6. Victoria University

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatial Inclusion and Environmental Justice: Accessibility, Mobility, and Sensory Experience

5.2. Cultural Representation and Recognition in Campus Space

5.3. Pedagogical Flexibility and Informal Learning: Spatialising Inclusive Education

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Times Higher Education. World University Rankings 2025; Times Higher Education: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. Key Findings from the 2023 Higher Education Student Statistics. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/student-data/selected-higher-education-statistics-2023-student-data/key-findings-2023-student-data#ftn1 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Zallio, M.; Clarkson, P.J. Inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility in the built environment: A study of architectural design practice. Build. Environ. 2021, 206, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, A.; Van der Linden, V.; Van Steenwinkel, I. Ten questions concerning inclusive design of the built environment. Build. Environ. 2017, 114, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaven, A.-M. Considering the sensory and social needs of disabled students in higher education: A call to return to the roots of universal design. Policy Futures Educ. 2024, 23, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, E.; Greenop, K. Affirming and Reaffirming Indigenous Presence: Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community, Public and Institutional Architecture in Australia. In The Handbook of Contemporary Indigenous Architecture; Grant, E., Greenop, K., Refiti, A.L., Glenn, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 57–106. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Gqola, P.D.; Perera, I.; Phadke, S.; Shahrokni, N.; Zaragocin, S.; Satija, S.; Ghosh, A. Gender and public space. Gend. Dev. 2024, 32, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.S.Y.; Gou, Z.; Liu, Y. Healthy campus by open space design: Approaches and guidelines. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, B.; Pini, B.; Bryant, L. Experiencing and writing Indigeneity, rurality and gender: Australian reflections. J. Rural Stud. 2009, 25, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataee, S.; Lopes, M.; Relvas, H. Environmental comfort in urban spaces: A systematic literature review and a system dynamics analysis. Urban Clim. 2025, 60, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira da Silva, F. Inclusive Design is Much More Than the Opposite of Exclusive Design. In Perspectives on Design and Digital Communication III: Research, Innovations and Best Practices; Martins, N., Brandão, D., Paiva, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Theroux, R. Conceptualizing the Campus Culture: The Significance of Cultural Artifacts. N. Y. J. Stud. Aff. 2022, 22, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, H.; Åhman, H.; Yngling, A.A.; Gulliksen, J. Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: Different concepts—One goal? On the concept of accessibility—Historical, methodological and philosophical aspects. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanteigne, V.; Rider, T.R.; Stratton, P.A. Inclusive Building Performance: A New Design Paradigm. In Design for Inclusivity, Proceedings of the UIA World Congress of Architects Copenhagen 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2–6 July 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 783–791. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, R.; Hardie, G.; Place, J. Toward universal design. In Design Intervention (Routledge Revivals): Toward a More Humane Architecture; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: Oxfordshire, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, B.R.; Jones, M.; Mace, R.; Mueller, J.; Mullick, A.; Ostroff, E.; Sanford, J.; Steinfeld, E.; Story, M.; Vanderheiden, G. The Principles of Universal Design; The Center for Universal Design: Raleigh, NC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.S.; Loewen, G.; Funckes, C.; Kroeger, S. Implementing Universal Design in Higher Education: Moving Beyond the Built Environment. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2003, 16, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Burgstahler, S. Universal Design in Education: Principles and Applications. Available online: https://doit.uw.edu/brief/universal-design-in-education-principles-and-applications/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Kivelä, M. Flexibility and Predictability: Change, Furniture Arrangements and Pedagogical Communication. J. Learn. Spaces 2023, 12, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Galkienė, A.; Monkevičienė, O. Improving Inclusive Education through Universal Design for Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cadena, R.P.; Andrade, M.O.d.; Meira, L.H.; Douradod, A.B.d.F. The pursuit of a sustainable and accessible mobility on university campuses. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 48, 1861–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogli, D.; Arenghi, A.; Gentilin, F. A universal design approach to wayfinding and navigation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 79, 33577–33601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humes, L.E.; Young, L.A. Sensory–Cognitive Interactions in Older Adults. Ear Hear. 2016, 37, 52S–61S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, L.; Vasalou, A.; Khaled, R.; Johnson, H.; Gooch, D. Diversity for design: A framework for involving neurodiverse children in the technology design process. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; pp. 3747–3756. [Google Scholar]

- Watchorn, V.; Hitch, D.; Tucker, R.; Frawley, P.; Aedy, K.; Grant, C. Evaluating universal design of built environments: An empirical study of stakeholder practice and perceptions. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2023, 38, 1491–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhami, H.; Berkouk, D.; Bouzir, T.A.K.; Khelil, S.; Gomaa, M.M. The Influence of Multisensory Perception on Student Outdoor Comfort in University Campus Design. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Senses of place: Architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, H.; Crippen, A.; Hawkey, C.; Dalrymple, M. A ROADMAP FOR BUILDING CLIMATE RESILIENCE AT HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS: A CASE STUDY OF ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY. J. Green Build. 2020, 15, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Choi, A.; Dekker, K.; Metzler, D. The Social Cost of Automobility, Cycling and Walking in the European Union. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 158, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, G.; Volakaki, M.-G.; Kokolakis, S.; Vouyioukas, D. Learning Spaces in Higher Education: A State-of-the-Art Review. Trends High. Educ. 2023, 2, 526–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disability Access and Inclusion Plan Report 2021–2025. Available online: https://www.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-12/Disability%20Access%20and%20Inclusion%20Plan%202021%E2%80%932025.PDF (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wayfinding and Signage Case Study Diadem. Available online: https://diadem.co/projects/deakin-university (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Waurn Ponds Campus Map. Available online: https://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/817367/geelong-waurn-ponds-campus-map.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Deakin Delama Walk Map. Available online: https://www.deakin.edu.au/about-deakin/values-and-culture/sustainability/sustainability-on-campus/deakin-delama-walk (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Physical Access Campus Maps. Available online: https://www.latrobe.edu.au/students/support/wellbeing/services/accessability-hub/physical-access-and-maps (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Signage Style Guide V2-0.CDR. Available online: https://www.latrobe.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/593720/G114-La-Trobe-University-Signage-Style-Guide.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Indigenous Student Services. Available online: https://www.latrobe.edu.au/indigenous/student-services (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Monash University Clayton Campus Master Plan Update 2024—Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/3785113/Clayton-Campus-MP-Update-2024_Executive-Summary_low-res.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Monash Design and Construction Standards. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/3950824/MDCS-2025.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Monash University Clayton Campus Map. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/2658973/Clayton-campus-map.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Monash Digital Wayfinding. Available online: https://maps.monash.edu/#v=1&zlevel=2¢er=145.135776,-37.913017&zoom=15.98&campusid=159 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Framework 2022–2030. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/3225358/EDI-Framework-Booklet.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Gardens at Clayton. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/about/our-locations/clayton-campus/gardens-at-clayton (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Monash Unviersity Strategic Plan 2021–2030. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/2680389/Strategic-Plan-2030.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Enviornmental, Social and Goverance Statement 2021–2025. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/2707483/ESG-Statement-2021-2025.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Sustainable Transport Plan. Available online: https://www.rmit.edu.au/about/our-values/sustainability/life-on-campus/sustainable-transport#:~:text=RMIT%20Sustainable%20Transport%20Plan,cycle%20and%20use%20public%20transport (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- RMIT Design Standards. Available online: https://www.rmit.edu.au/content/dam/rmit/au/en/about/locations-and-facilities/safety-and-security/design-standards-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- RMIT University Signage Design Standards. Available online: https://www.rmit.edu.au/content/dam/rmit/au/en/about/locations-and-facilities/safety-and-security/signage-design-standards.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Inclusive and Accessible Events Guide. Available online: https://www.rmit.edu.au/content/dam/rmit/au/en/about/our-values/diversity-and-inclusion/inclusive-and-accessible-events-guide.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Thermal Comfort Guidance. Available online: https://www.rmit.edu.au/content/dam/rmit/au/en/about/our-values/health-safety-wellbeing/global-safety-model/safety-topics/HR-HSW-PR35-WI03-thermal-comfort-guidance.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- City Campus Mobility Map. Available online: https://www.rmit.edu.au/content/dam/rmit/documents/maps/pdf-maps/rmit-melbourne-city-campus-map.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Design Standards: Campus Design and Planning (Currently Under Development). Available online: https://about.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/413246/University-of-Melbourne-Design-Standards,-combined-2023.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Bicycle Map. Available online: https://sustainablecampus.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/2080832/Map_2015_rev34_Grey_BP.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Design Standards: Grounds and Landscaping Standards. Available online: https://about.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/414830/Sect-15-Grounds-Landscaping-incl-appendices-6-Feb-2024_-002.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- University of Melbourne Signage Guidelines. Available online: https://about.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0028/75619/UoM-Signage-Guidelines-02.19-v13.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- The University of Melbourne Indigenous Strategy 2023–2027. Available online: https://www.unimelb.edu.au/indigenous/governance/indigenous-strategies-and-reports (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Footscray Park Campus Access and Mobiliity Map. Available online: https://www.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/facilities/pdfs/footscray-park-access-and-mobility-map.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Attorney-General’s Department. Disability Standards for Education 2005. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2005L00767/latest/text (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Student Accessiblity Action Plan 2021–2023. Available online: https://content.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/student-accessibility-action-plan.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Brilliant Together: Cultural Inclusion and Racial Equality Plan 2023–2026. Available online: https://content.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/2024-01/brilliant-together-cultural-inclusion-racial-equality-plan-2023-2026.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Tangalakis, K.; Cuong Huu, H.; Elizabeth, K.; Peter, H.; Jennifer, J.; Hildebrandt, M. Differentiation through innovation in the contemporary higher education environment: The case of the ‘Victoria University Block Model®’. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2024, 61, 1305–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, H.W.; Jamei, E.; Li, M. Block mode delivery for studio design teaching in higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2023, 60, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Observation Aspect | What to Look for on Campus | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Inclusion and Equity | Accessible routes (ramps, lifts), tactile paving, seating variety, proximity of amenities | [6] |

| Navigability and Wayfinding | Multilingual signage, intuitive spatial layout, sensory-friendly design (visual, tactile, auditory cues) | [4] |

| Cultural and Social Recognition | Indigenous design elements, gender-neutral spaces, prayer/multifaith rooms, cultural centres | [9] [7] [11] |

| Informal and Social Learning Spaces | Outdoor study areas, student hubs, shaded courtyards, breakout zones | [10] |

| Environmental and Sensory Comfort | Thermal comfort, light access, acoustic quality, access to greenery and shade | [12] |

| Mobility and Connectivity | Walkability, bike lanes/parking, shared paths, public transport links | [31] |

| Support Infrastructure for Equity | Disability services, counselling centres, academic support hubs, inclusive library design | [5] |

| Pedagogical Flexibility and Responsiveness | Modular classrooms, pop-up studios, hybrid learning zones, makerspaces | [32] |

| Observation Aspect | The University of Melbourne | RMIT University | Deakin University | La Trobe University | Monash University | Victoria University |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Inclusion and Equity | Ramps, lifts, and tactile paving are widely present, especially in Arts West and The Spot; aligns with universal design standards. | Accessibility features such as ramps, tactile paving, and lifts are prominent across campus, especially in Building 80; aligns with urban density and equity principles. | Accessible routes, seating variety, and amenity proximity are generally well provided, although tactile paving is not consistently visible throughout the campus. | Ramps and lifts are widely available; tactile paving limited. | Accessibility infrastructures included ramps, accessible lifts, tactile paving, and automatic doors. For restricted areas there are card readers or buttons at wheelchair level. | Ramps, lifts, and accessible parking, and staircases with bike ramps are available across the campus. |

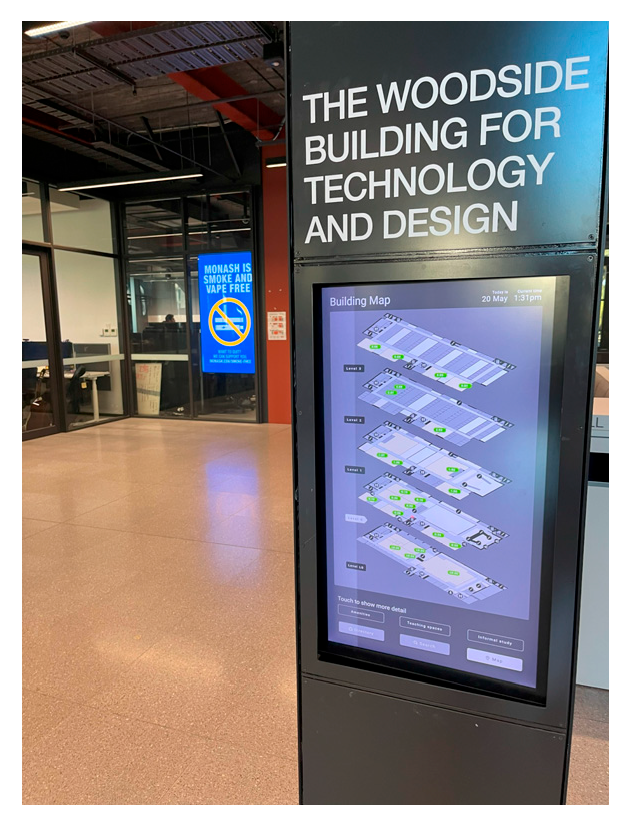

| Navigability and Wayfinding | Multilingual signage and intuitive layouts aid navigation; sensory rooms exist in libraries; visual and auditory cues enhance access. | Clear numbering system and external signage support exterior navigation; however, interior signage is inconsistent, relying on temporary posters; level changes can be confusing. | Wayfinding system with zoning and signage is effective; Multilingual signage and sensory-based wayfinding cues are limited. | A formal signage system exists with clear building codes. However, multilingual signage and sensory navigation cues are generally lacking., | Very detailed information board with maps using the combination of colour code and numbering systems. Some buildings have touch screen maps to help locate specific rooms or facilities. Library has designated sensory study spaces and an acoustic study pod | The information board available at key entrance points with alphabetical letters for labelling different buildings. |

| Cultural and Social Recognition | Gender-neutral toilets, Indigenous artwork, and multifaith prayer rooms (e.g., David Caro and Chemistry West buildings) are well-distributed. | Indigenous features like Ngarara Place, all-gender toilets, and the Multifaith and Wellbeing Centre in Building 47 enhance cultural inclusion. | Indigenous presence through the Delama Dja Walk, plus multifaith rooms, gender-neutral toilets, and LGBTIQ+ spaces available in central areas. | Strong Indigenous presence through Gabra Biik and Indigenous art around campus. Multifaith prayer rooms are available and gender-neutral toilets exist in several buildings | Religious Centre with multifaith prayer rooms. Indigenous features such as the Aboriginal park. Queer lounge, Parent room located in the Campus Centre. All-gender toilets are available in most buildings | Indigenous features included the Moondani Balluk centre next to the indigenous garden with a fireplace for smoke ceremonies. Prayer room, Parent room, Pride room and a quiet room available. |

| Informal and Social Learning Spaces | South Lawn and the Student Pavilion provide flexible, shaded spaces for silent and group study; indoor study zones support varied preferences. | Swanston Library includes study pods and breakout zones; open-air courtyards in Building 11 and Alumni Court support social learning. | Outdoor study areas, student hubs, and shaded courtyards are available across the campus, particularly in renovated precincts. | Outdoor study areas, student hubs, and shaded courtyards are available across the campus, particularly in renovated precincts. | Multiple gardens and courtyards (e.g., Kenneth Hunt Garden) provide informal outdoor learning and social space. Many buildings (e.g., the Learning and Teaching Building, Woodside Building) have atrium stairs for indoor study spaces. | Courtyards around Building P provide social spaces for recreational activities and student clubs to hold events. There are group study cubes and a student lodge inside Building P and M as breakout zones. |

| Environmental and Sensory Comfort | Landscape integration supports thermal comfort; access to daylight and acoustic zoning observed; passive design principles embedded in standards. | Courtyard and open-air spaces promote passive comfort; campus follows sustainability and acoustic/thermal comfort guidelines. | Buildings offer good daylight access, natural ventilation, and visual connection to greenery; acoustic design is not clearly documented. | Campus landscape includes shaded walkways, large green spaces, and passive comfort strategies. | The range of courtyards and gardens created a different tone of sensory spaces, that meet the requirements of Monash Design and Construction Standards | Most buildings have installed motion sensors to control lighting to avoid wasting energy when there are no occupants. Quiet study zone can easily find in Building C and D with acoustic panels and overhead spotlights. |

| Mobility and Connectivity | Bike parking, pedestrian pathways, and tram connections ensure sustainable access; the parkland layout supports safe and accessible navigation. | Well-connected through walkable streets, bike paths, and tram links; urban integration supports permeability and social interaction. | Campus supports walking, cycling (bike lanes and parking), and is well-connected to public transport, with recent upgrades enhancing safety. | The campus is walkable, with strong public transport access and excellent bike facilities | Well-connected campus with infrastructures highly integrated with bikes, buses, and electric vehicles. Zero obstacles when moving across the campus and travel between buildings. | Public transportations are not directly located on campus. Bike and motorbike have better access inside the campus. The campus is set on a hillslope, can be difficult to move between levels. |

| Support Infrastructure for Equity | Adaptive furniture in Baillieu Library; access to counselling and disability services; inclusive signage for library zones. | Sensory-friendly rooms in Swanston Library; lecture theatres equipped with assistive tech and adjustable furnishings. | Disability support services, counselling, academic help, and inclusive library features are clearly integrated and easy to access. | The Accessibility Hub, counselling services, and inclusive library design support diverse student needs and are well-signposted | Adaptive technology room and acoustic study pod available in the Hargrave-Andrew Library. Lecture theatre and classrooms are equipped with a hearing aid system. | Classrooms are equipped with hearing aid systems, movable chairs and adjustable tables for specific needs. Water fountains are built on wheelchair levels |

| Pedagogical Flexibility and Responsiveness | The Spot features modular classrooms and hybrid learning spaces aligned with flexible and inclusive pedagogical models. | Modular classrooms and hybrid zones in the Swanston Building demonstrate flexible, hands-on pedagogical support. | Modular classrooms, hybrid zones, and advanced learning spaces like the Nyaal precinct and CADET are available, especially in recent developments. | Hybrid zones and modern learning spaces are available in some new buildings, but not consistent across all faculties or older blocks. | Learning and Teaching buildings and the Woodside buildings consist of modular classrooms, hybrid learning spaces that allow interactive learning and teaching pedagogy. | Modular classrooms are designed with digital equipment that adapts to online or hybrid learning and student engagement for the VU Block Model pedagogy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, S.; Wai, C.Y.; Zhang, J.; Geng, S.; Wei, J.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E. Designing for Inclusion: A Comparative Analysis of Inclusive Campus Planning Across Australian Universities. Architecture 2025, 5, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030043

Yan S, Wai CY, Zhang J, Geng S, Wei J, Chau H-W, Jamei E. Designing for Inclusion: A Comparative Analysis of Inclusive Campus Planning Across Australian Universities. Architecture. 2025; 5(3):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030043

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Se, Cheuk Yin Wai, Jia Zhang, Shiran Geng, Jinxi Wei, Hing-Wah Chau, and Elmira Jamei. 2025. "Designing for Inclusion: A Comparative Analysis of Inclusive Campus Planning Across Australian Universities" Architecture 5, no. 3: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030043

APA StyleYan, S., Wai, C. Y., Zhang, J., Geng, S., Wei, J., Chau, H.-W., & Jamei, E. (2025). Designing for Inclusion: A Comparative Analysis of Inclusive Campus Planning Across Australian Universities. Architecture, 5(3), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030043