Unfreezing the City: A Systemic Approach to Arctic Urban Comfort

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To develop a context-sensitive theoretical framework for urban environmental formation in Russian Arctic cities.

- To conceptualize urban lived space as a design context that integrates representations, perceptions, and materiality.

- To propose and validate the concept of a life support module (LSM) as a new approach to Arctic urban design.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.2. Field Research Sites and Data Collection

2.3. Research Methods

- In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with local residents in both Novyy Urengoy and Tarko-Sale (The interview guide, interview transcripts, and mental maps are available in the original language (Russian) only and therefore are not included in the appendix to this article. These materials can be made available upon request from the authors) (n = 11 in total).

- Mental mapping exercises were used to understand residents’ perception of the urban environment (n = 7 in total). Participants were asked to sketch their urban experiences, marking significant locations and regular routes while providing emotional associations with different areas.

- Two biographical walks were conducted with local residents to document their daily experiences and interactions with the urban environment.

- Systematic observation of urban life was maintained throughout the field trip, documented through detailed field notes.

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Conceptual Framework: Context Sensitivity

3.2. Empirical Data: Local Practices, Identity, and Perceptions

3.3. Conceptual Framework: Lived Space as a Design Context

- Determine the structure and interconnections of both the design object and its context, incorporating them into a design system.

- Embody the “human pathways” into the system and therefore ground the design actions into a particular lived context.

- Define the overarching design goal and specific objectives for each level of the model.

- Materiality of the built environment, accommodating practices and routines—material perspective (urban materiality and practices), representing the perceived experience within the lived space.

- Socio-cultural context—conceptual perspective (ideas and meanings), reflecting the conceived understanding of the lived space.

- Dwelling perspective (lived experience), capturing the overall essence of the lived space as a direct experience of urban life and its various dimensions—both ideal and material.

3.4. Conceptual Framework: Life Support Module as a Design Object

- Material affordances (the combination of physical and functional), which create an adequate urban environment that enables the comfort of everyday practices.

- Conceptual affordances, which allow the connection of identity to the place and the formation of an attachment to it.

- Perceptual/sensual affordances, which provide opportunities to sensually perceive and form an emotional impression.

- Adapted (creates sustainable comfort under specific conditions by including context in the systemic design process).

- Adaptive (adjusts its content to the changing context while focusing on targeted goals, which ensures resilience).

- Harmonious (ensures the equilibrium between environmental sustainability and the diverse needs of city inhabitants by providing a single, holistic solution for a systemic issue).

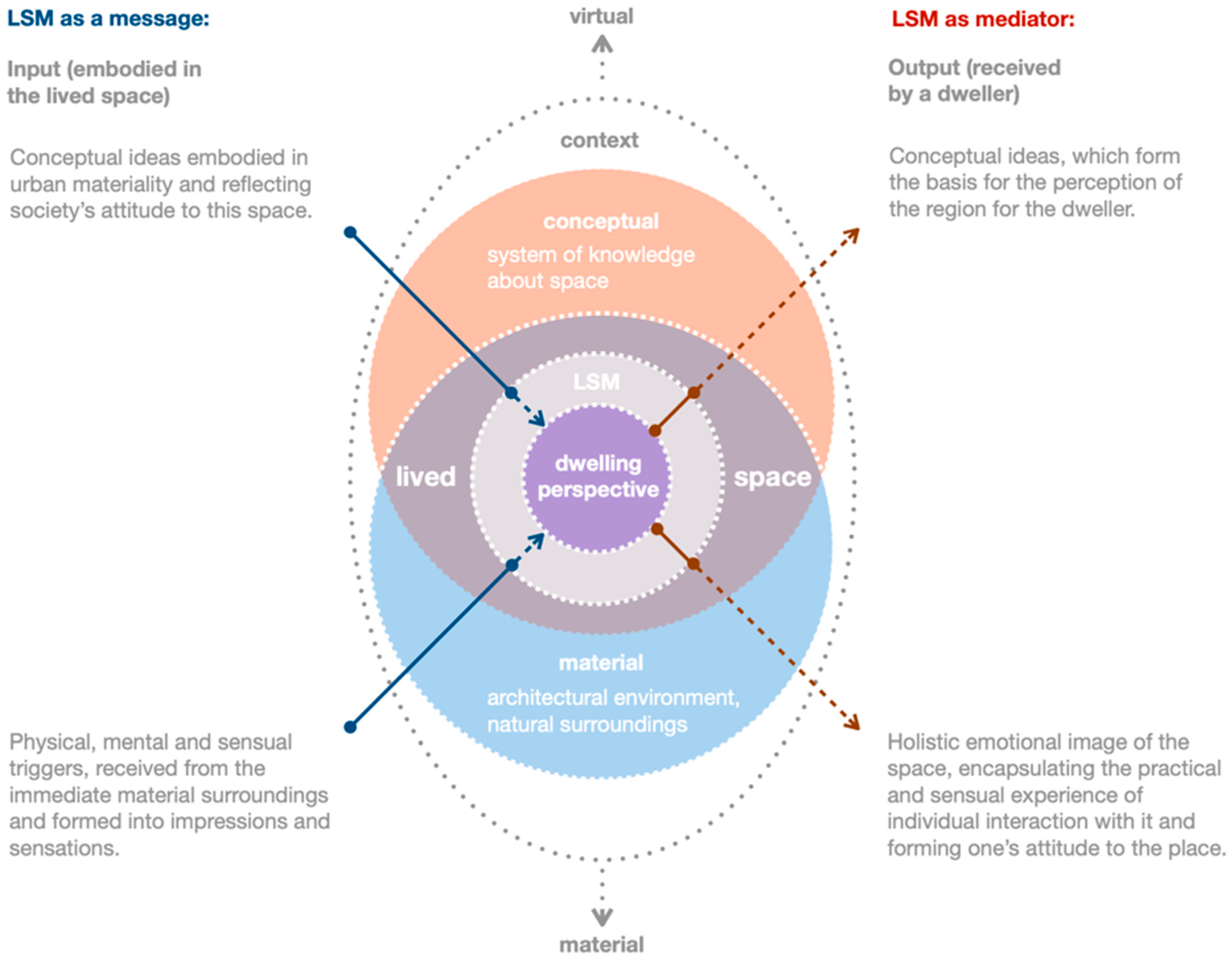

3.5. Life Support Module as a Medium

3.6. Life Support Module as a Message

- As an intermediate mediator, LSM influences our sensory perception and behavior. The urban experience, shaped by our interaction with the module, creates a foundation for conceptual ideas that inform our understanding of the city and the surrounding region. Additionally, it fosters a comprehensive emotional image of the area, capturing the practical sensory experiences derived from an individual’s engagement with their environment, as mediated by the LSM.

- As a message, the LSM embodies narratives embedded in the urban environment through the social production of space. These narratives shape our conceptual understanding of the place, while sensory triggers—such as visual, auditory, and tactile cues—contribute to the overall impressions formed by dwellers. The LSM, therefore, serves as a medium through which urban space communicates its cultural, social, and environmental significance.

- The overarching urban space model (“Lived space”) alongside the challenges faced in Arctic urban planning (“Arctic city context”), derived from an extensive review of the literature on the development and current state of Russian Arctic cities (e.g., [2,3,4,5,6,8,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] and other studies). Our analysis was further informed by field data, particularly observational studies of physical spaces.

- “LSM as a medium”, which illustrates the interconnections between the model’s levels and the associated levels of LSM, framed within the theoretical context of media studies, and further detailed in “LSM levels of adaptation”.

- “Design system objectives”, which clarify the primary goals for each level, acting as focal points throughout the ongoing cycles of LSM adaptation.

- The “Context-sensitive analyses section” examines potential avenues for future context-sensitive research aligned with the defined levels, suggesting practical applications of the proposed theoretical framework as a methodology for the design process.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Life Support Module: Theoretical Principles and Their Practical Significance

4.2. Critical Challenges in Arctic Urban Design

4.3. Towards Context-Sensitive Arctic Urbanism

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

- An extreme environment reinforces the protective role of the urban shell, emphasizing the research on the ways design can create sustainable physical comfort while encouraging interaction with open urban space.

- Given the importance of soft mobility as a tool for creating close city dweller relationships [51,77] and northerners’ appreciation of natural Arctic surroundings [17], there is a pressing need for targeted field research on the way people interact with the Arctic urban environment, as well as for conceptual design tools for creating a diversity of seasonal practices.

- Highlighting perceptual space as the central element of the model emphasizes targeted field research on how dwellers emotionally/mentally perceive a city. Based on these findings, a design intervention could be implemented to transform this image. This approach implies a phenomenological analysis of the relationships between the body, technological medium, and city, as well as conceptualizing the desired image of a friendly, warm, and welcoming urban environment.

- There is a need for design interpretation of local identity, based on socio-cultural and anthropological research of Russian Arctic cities (which is a rather developed research sphere compared to Arctic architecture and design), in order to overcome the centralized design perspective on locality.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buchanan, R. Systems thinking and design thinking: The search for principles in the world we are making. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2019, 2, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotova, A. Colonization of Nature in the Soviet Union. State Ideology, Public Discourse, and the Experience of Geologists. Hist. Soc. Res./Hist. Soz. 2004, 29, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laruelle, M. Russia’s Arctic Strategies and the Future of the Far North, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmersam, P. Making the Arctic City: The History and Future of Urbanism in the Circumpolar North, 1st ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shiklomanov, N.I.; Laruelle, M. A truly Arctic city: An introduction to the special issue on the city of Norilsk, Russia. Polar Geogr. 2017, 40, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemeneva, E. From New Socialist Cities to Thaw Experimentation in Arctic Townscapes: Leningrad Architects Attempt to Modernise the Soviet North. Eur.-Asia Stud. 2019, 71, 426–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huse, T. Temporal displacement: Colonial architecture and its contestation. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jull, M. The improbable city: Adaptations of an Arctic metropolis. Polar Geogr. 2017, 40, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechsiri, J.S.; Sattari, A.; Martinez, P.G.; Xuan, L. A review of the climate-change-impacts’ rates of change in the Arctic. J. Environ. Prot. 2010, 1, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppäluoto, J.; Hassi, J. Human Physiological Adaptations to the Arctic Climate. Arctic 1991, 44, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggan, G. Introduction: Unscrambling the Arctic. In Postcolonial Perspectives on the European High North. Unscrambling the Arctic, 1st ed.; Huggan, G., Jensen, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, A. A theory of systemic design. In Relating Systems Thinking and Design 2013 Symposium Proceedings, Oslo, Norway, 9–11 October 2013; 2013; Available online: http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/2162/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Ridell, S. The city as a medium of media: Public life and agency at the intersections of the digitally shaped urban space. In Media and The City: Urbanism, Technology and Communication, 1st ed.; Tosoni, S., Tarantino, M., Giaccardi, C., Eds.; Cambridge Scholar Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013; pp. 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space, 1st ed.; Basil Blackwell Ltd: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. Space of flows, space of places: Materials for a theory of urbanism in the information age. In The City Reader, 1st ed.; LeGates, R.T., Stout, F., Caves, R.W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Bolotova, A. Loving and conquering nature: Shifting perceptions of the environment in the industrialised Russian North. Eur.-Asia Stud. 2012, 64, 645–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K.K. Mastering the Arctic? Political Culture and Colonialism in the Russian Far North. Ph.D. Thesis, The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway, September 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10037/31908 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Kalemeneva, E. Arctic Modernism: New Urbanisation Models for the Soviet Far North in the 1960s. In Competing Arctic Futures. Palgrave Studies in the History of Science and Technology, 1st ed.; Wormbs, N., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisser, C. Russia’s Arctic Cities. In Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities: Resource Politics, Migration, and Climate Change, 1st ed.; Orttnung, R.W., Ed.; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Stas’, I. An Indigenous Anthropocene: Subsistence Colonization and Ecological Imperialism in the Soviet Arctic in the 1920s and Early 1930s. Sov. Post-Sov. Rev. 2022, 49, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunko, M.; Batunova, E.; Medvedev, A. Rethinking urban form in a shrinking Arctic city. Espace Popul. Sociétés Space Popul. Soc. 2021. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/eps/10630#citedby 31908 (accessed on 17 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gunko, M.; Zupan, D.; Riabova, L.; Zaika, Y.; Medvedev, A. From policy mobility to top-down policy transfer: “Comfortization” of Russian cities beyond neoliberal rationality. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2022, 40, 1382–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinossian, N. Re-colonising the Arctic: The preparation of spatial planning policy in Murmansk Oblast, Russia. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2017, 35, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyanov, B.C. Arkticheskiy makroregion Rossii: ot severnogo frontira k severnomu El’dorado? [Russia’s Arctic macro-region: From northern frontier to northern Eldorado?]. Dnev. Altaj. Shkoly Politicheskih Issled. 2015, 31, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, A.N.; Smith, M.S.R.; Krivorotov, A.K.; Klyuchnikova, E.M.; Mikheev, V.L.; Pelyasov, A.N.; Zamyatina, N.Y. The Russian Arctic by 2050: Developing Integrated Scenarios. Arctic 2021, 74, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamyatina, N.Y.; Goncharov, R.V. Arctic urbanization: A phenomenon and a comparative analysis. Lomonosov. Geogr. J. 2020, 4, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zamyatina, N.; Goncharov, R. “Agglomeration of flows”: Case of migration ties between the Arctic and the southern regions of Russia. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2022, 14, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamyatina, N. Vozmozhno li blagoustroystvo arkticheskikh gorodov: tri kartiny [Is the Improvement of Arctic Cities Possible: Three Pictures]. GoArctic 2023. Available online: https://goarctic.ru/society/vozmozhno-li-blagoustroystvo-arkticheskikh-gorodov-tri-kartiny/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Heleniak, T.E. The role of attachment to place in migration decisions of the population of the Russian North. Polar Geogr. 2009, 32, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castree, N.; Gregory, D. (Eds.) David Harvey: A Critical Reader; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Reading the city in a global digital age: Between topographic representation and spatialized power projects. In Global Cities: Cinema, Architecture, and Urbanism in a Digital Age, 1st ed.; Krause, L., Petro, P., Eds.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmidt, C. Henri Lefebvre, the right to the city, and the new metropolitan mainstream. In Cities for People, not for Profit. Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City, 1st ed.; Brenner, N., Marcuse, P., Mayer, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. Spaces of vulnerability: The space of flows and the politics of scale. Crit. Anthropol. 1996, 16, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E. Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions, 1st ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Soules, M. Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra-Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the 21st Century, 1st ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ackoff, R.L.; Emery, F.E. On Purposeful Systems: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Individual and Social Behavior as a System of Purposeful Events, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, H.G.; Stolterman, E. The Design Way: Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sevaldson, B. Redesigning systems thinking. FormAkademisk 2017, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.H. Systemic Design Principles for Complex Social Systems. In Social Systems and Design. Translational Systems Sciences, 1st ed.; Metcalf, G., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 91–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, T.A. Postcolonial Critique of Industrial Design: A Critical Evaluation of the Relationship of Culture and Hegemony to Design Practice and Education Since the Late 20th Century. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK, 20 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosagrahar, J. Interrogating difference: Postcolonial perspectives in architecture and urbanism. In The SAGE Handbook of Architectural Theory, 1st ed.; Crysler, C.G., Heynen, H., Cairns, S., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, L.; Vertesi, J.; Dourish, P.; Philip, K.; Grinter, R.E. Postcolonial computing: A lens on design and development. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1st ed.; Mynatt, E., Schoner, D., Fitzpatrick, G., Hudson, S., Edwards, K., Rodden, T., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1311–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Minnakhmetova, R.; Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Konkova, Y. A context-sensitive approach to the use of traditional ornament in contemporary design practice (with Reference to Western Siberian Ethnic Ornaments). Res. Arts Educ. 2019, 1, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M. On the phenomenology of technology: The “Janus-faces” of mobile phones. Inf. Org. 2003, 13, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergen, K.J. The challenge of absent presence. In Perpetual Contact, 1st ed.; Katz, J.E., Aakhus, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccardi, C. From tactile to magic: McLuhan, changing sensorium and contemporary culture. In Understanding Media, Today. McLuhan in the Age of Convergence Culture, 1st ed.; Ciastellardi, M., Patti, E., Eds.; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccardi, C. Whatever happened to Flanerie? On some theoretical implications of the media/city nexus. In Media and The City: Urbanism, Technology and Communication, 1st ed.; Tosoni, S., Tarantino, M., Giaccardi, C., Eds.; Cambridge Scholar Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013; pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Seamon, D. A Geography of the Lifeworld: Movement, Rest and Encounter, 1st ed.; St Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, R. Fancy footwork: Walter Benjamin’s notes on flânerie. In The Flaneur (RLE Social Theory), 1st ed.; Tester, K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, I.; Knez, I.; Westerberg, U.; Thorsson, S.; Lindberg, F. Climate and behaviour in a Nordic city. Landsc. Urb. Plan. 2007, 82, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiak, J. Being-in-the-City: A phenomenological approach to technological experience. Cult. Unbound 2009, 1, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zook, M.A.; Graham, M. Mapping DigiPlace: Geocoded Internet data and the representation of place. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2007, 34, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza e Silva, A. From cyber to hybrid: Mobile technologies as interfaces of hybrid spaces. Space Cult. 2006, 9, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza e Silva, A. Hybrid spaces 2.0: Connecting networked urbanism, uneven mobilities, and creativity, in a (post) pandemic world. Mob. Media Commun. 2023, 11, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, M. The City as Interface. How New Media Are Changing the City, 1st ed.; Nai: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, R. Technological determinism. In A Companion to Popular Culture, 1st ed.; Burns, G., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenlohr, P. Introduction: What is a medium? Theologies, technologies and aspirations. Soc. Anthropol. 2011, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, R. Topologies of human-mobile assemblages. In Mobile Technology and Place, 1st ed.; Wilken, R., Goggin, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Herzogenrath, B. Media/Matter: An Introduction. In Media|Matter: The Materiality of Media, Matter as Medium, 1st ed.; Herzogenrath, B., Bloomsbury, L., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, R.; Dodge, M. Code/Space: Software and Everyday Life, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler, F.A.; Griffin, M. The city is a medium. New Lit. Hist. 1996, 27, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krtilova, K. Media matter. Materiality and Performativity. In Media|Matter: The Materiality of Media, Matter as Medium, 1st ed.; Herzogenrath, B., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2015; pp. 28–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarella, W. Culture, Globalization, Mediation. Ann. Rev. Anthrop. 2004, 33, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLuhan, M. Understanding Media, 1st ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- McQuire, S. The Media City: Media, Architecture and Urban Space, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W.J. City of Bits: Space, Place, and the Infobahn, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Strate, L. Studying media as media: McLuhan and the media ecology approach. MediaTropes Ejournal 2008, 1, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Population of the Russian Federation by Municipalities. Federal State Statistical Service. Available online: https://rosstat.gov.ru/compendium/document/13282 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Garin, N.; Usenyuk, S.; Kukanov, D.; Gostyaeva, M.; Kon’kova, Y.; Rogova, A. Shkola Severnogo Dizayna. Arktika Vnutri: Al’bom-Monografiya [Arctic Design School. The Arctic Within: A Monograph Album]; USUAA: Ekaterinburg, Russia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rydin, Y. Re-examining the role of knowledge within planning theory. Plan. Theory 2007, 6, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, L.; Bridgman, R. Towards cosmopolis: Planning for multicultural cities. Can. J. Urban Res. 1999, 8, 108. [Google Scholar]

- Baha, E.; Singh, A. Challenging the North-South Divide in Decolonizing Design. Diseña 2024, 25, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunstall, E.D. Decolonizing Design: A Cultural Justice Guidebook, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Marcuse, P.; Mayer, M. (Eds.) Cities for People, not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Büdenbender, M.; Zupan, D. The evolution of neoliberal urbanism in Moscow, 1992–2015. Antipode 2017, 49, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, M. Cities and Natural Process, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McHarg, I.L. Design with Nature, 25th Anniversary ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Toward a critical regionalism: Six points for an architecture of resistance. In Postmodernism, 1st ed.; Dochery, T., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; pp. 268–280. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius loci: Towards a phenomenology of architecture. Hist. Cit. Iss. Urb. Cons. 1979, 8, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Overland, J.E. Arctic Climate Extremes. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakhtin, N.; Dudek, S.H. (Eds.) Deti 90-kh v Rossiyskoy Arktike [Children of the Nineties in the Modern Russian Arctic: A Collective Monograph]; Publishing House of the European University in St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bolotova, A.; Karaseva, A.; Vasilyeva, V. Mobility and sense of place among youth in the Russian Arctic. Sibirica 2017, 16, 77–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laruelle, M. The three waves of Arctic urbanization. Drivers, evolutions, prospects. Polar Rec. 2019, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanacek, K.; Kröger, M.; Martinez-Alier, J. Green and climate colonialities: Evidence from Arctic extractivisms. J. Polit. Ecol. 2017, 31, 538–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreter von Kreudenstein, S. Destructed Environments, Gendered Spaces and Colonial Legacies. Contemporary Artistic Practices Sensing the Arctic and the Circumpolar North. Ph.D. Thesis, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway, 13 January 2024. Available online: https://munin.uit.no/handle/10037/35862?locale-attribute=en (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Chapman, D.; Nilsson, K.L.; Rizzo, A.; Larsson, A. Updating winter: The importance of climate-sensitive urban design for winter settlements. Arct. Yearb. 2018. Available online: https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2018/2018-scholarly-papers/271-updating-winter-the-importance-of-climate-sensitive-urban-design-for-winter-settlements (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Wormbs, N. (Ed.) Competing Arctic Futures: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Gostyaeva, M.; Raeva, A.; Garin, N. Encountering the extreme environment through tourism: The Arctic design approach. J. Dest. Market. Manag. 2021, 19, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Akimenko, D.; Garin, N.; Miettinen, S. Arctic Design for the Real World: Basic Concepts and Educational Practice. In DS 104: Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, 1st ed.; Bisgaard, A., McElheron, P.J., Therkildsen, M., Buck, L., Bohemia, E., Grierson, H., Eds.; VIA University: Herning, Denmark, 2020; Available online: https://www.designsociety.org/publication/43089/DS+104%3A+Proceedings+of+the+22nd+International+Conference+on+Engineering+and+Product+Design+Education+%28E%26PDE+2020%29%2C+VIA+Design%2C+VIA+University+in+Herning%2C+Denmark.+10th+-11th+September+2020 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Buchanan, R. Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Des. Issues 1992, 8, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S. Spatializing Culture: The Ethnography of Space and Place; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carp, J. “Ground-truthing” representations of social space: Using Lefebvre’s conceptual triad. J. Plan. Ed. Res. 2008, 28, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, N. Lefebvre for Architects; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. A cautious Prometheus? A few steps toward a philosophy of design (with special attention to Peter Sloterdijk). In Networks of Design. Proceedings of the 2008 Annual International Conference of the Design History Society (UK) University College Falmouth, 3–6 September, 1st ed.; Hackney, F., Glynne, J., Minton, V., Eds.; BrownWalker Press: Irvine, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Klauser, F.R. Splintering spheres of security: Peter Sloterdijk and the contemporary fortress city. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2010, 28, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Norman, D. The Design of Everyday Things; Basic Books, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton-Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hartson, R. Cognitive, physical, sensory, and functional affordances in interaction design. Behav. Inf. Tech. 2003, 22, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jull, M. Toward a Northern architecture: The microrayon as Arctic urban prototype. J. Arch. Ed. 2016, 70, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, R.; Pechkina, Y.; Kuklina, V.; Michugin, M.; Soromotin, A. Urban Trees in the Arctic City: Case of Nadym. Land 2022, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y. Architectural lessons from environmental psychology: The case of biophilic architecture. Rev. Gen. Psych. 2007, 11, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammler, F.; Sidorova, L. Dachas on permafrost: The creation of nature among Arctic Russian city-dwellers. Polar Rec. 2015, 51, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.T.; Lin, T.P.; Lien, H.C. Investigating thermal comfort and user behaviors in outdoor spaces: A seasonal and spatial perspective. Adv. Met. 2015, 1, 423508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; Chapman, D. Perceived impact of meteorological conditions on the use of public space in winter settlements. Int. J. Biomet. 2020, 64, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, A.A.; Konstantinov, P.I.; Varentsov, M.I.; Samsonov, T.E. Modeling the dynamics of comfort thermal conditions in Arctic cities under regional climate change. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 386, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, P.I.; Shartova, N.; Varentsov, M.; Revich, B.A. Evaluation of outdoor thermal comfort conditions in northern Russia over 30-year period: Arkhangelsk region. Geogr. Pannonica 2020, 24, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gommershtadt, O.; Konstantinov, P.I.; Varentsov, M. Modeling of summer thermal comfort conditions of Arctic city on microscale. In Green Technologies and Infrastructure to Enhance Urban Ecosystem Services; Vasenev, V., Dovletyarova, E., Cheng, Z., Valentini, R., Calfapietra, C., Eds.; Springer Geography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimabadi, S.; Nilsson, K.L.; Johansson, C. The problems of addressing microclimate factors in urban planning of the subarctic regions. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2015, 42, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulé, C.I.; De Coninck, P. The Concept of “Nordicity”. Opportunities for the Design Fields. In Relate North: Practising Place, Heritage, Art & Design for Creative Communities; Jokela, T., Coutts, G., Eds.; Lapland University Press: Rovaniemi, Finland, 2018; pp. 12–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama, Y.; Oku, T.; Mori, S. The Changing Appearance of Color of Architecture in Northern City: A Comparison Study of Architecture’s Appearance in Summer and in Winter, in Sapporo City. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2005, 4, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change, 1st ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Existence, Space and Architecture, 2nd ed.; Praeger Publishers: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. Simulacra and Simulation, 1st ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- LeGates, R.T.; Stout, F.; Caves, R.W. (Eds.) The City Reader, 7th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bollnow, O.F. Lived-space. Philos. Today 1961, 5, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. Embodied, situated, and distributed cognition. In A Companion to Cognitive Science; Bechtel, W., Graham, G., Eds.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 506–517. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, N.E. Sustainable winter cities: Future directions for planning, policy and design. Atmos. Environ. 1996, 30, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibowitz, K.; Vittersø, J. Winter is coming: Wintertime mindset and wellbeing in Norway. Int. J. Wellbeing 2020, 10, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulé, C.I.; Evans, P. Living in the Near North: Insights from Fennoscandia, Japan and Canada. In Relate North: Tradition and Innovation in Art and Design Education, 1st ed.; Jokela, T., Coutts, G., Eds.; InSEA Publications: Viseu, Portugal, 2020; pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulé, C.I. Design as a Strategic Tool for Sustainability in Northern and Arctic Contexts: Case Study of the Arctic Design Concept in Finland. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, 17 October 2018. Available online: https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/handle/1866/21226 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Hidman, E. Attractiveness in Urban Design: A Study of the Production of Attractive Places. Ph.D. Thesis, Luleå tekniska Universitet, Luleå, Sweden, 11 August 2018. Available online: https://ltu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1247914&dswid=-1543 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Hamelin, L.E. Canadian Nordicity: It’s Your North, too, 1st ed.; Harvest House Limited Publishers: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, M.; Collins, D.; Stadler, S.L.; Soans, R.; Sanborn, E.; Summers, R.J. “Celebrated, not just endured”: Rethinking winter cities. Geog. Comp. 2018, 12, e12379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomer, K.C.; Moore, C.W.; Yudell, R.J.; Yudell, B. Body, Memory, and Architecture, 1st ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bognar, B. A phenomenological approach to architecture and its teaching in the design studio. In Dwelling, Place and Environment: Towards a Phenomenology of Person and World; Seamon, D., Mugerauer, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City 2015, 19, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härkönen, E. Teach me your arctic: Place-based intercultural approaches in art education. J. Cult. Res. Art Ed. 2018, 35, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokela, T.; Coutts, G. The North and the Arctic: A laboratory of art and design education for sustainability. In Relate North: Practising Place, Heritage, Art & Design for Creative Communities; Jokela, T., Coutts, G., Eds.; Lapland University Press: Rovaniemi, Finland, 2018; pp. 98–117. [Google Scholar]

- Landström, A. Places of Meaning and Belonging in the Urban Arctic: A Study on Place Attachment, Place Identity and the Impacts of Change in Rovaniemi City Center. Master’s Thesis, University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland, 2022. Available online: https://lauda.ulapland.fi/handle/10024/65137 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Sjöholm, J. Heritagisation, Re-Heritagisation and De-Heritagisation of Built Environments: The Urban Transformation of Kiruna, Sweden. Ph.D. Thesis, Luleå Tekniska Universitet, Luleå, Sweden, 2016. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:998892/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Karlsson, R. Mining the City: Urban Transformation and the Loss of City Space in Kiruna, Sweden. Master’s Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. Available online: https://su.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1621453&dswid=-5193 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Hyysalo, S.; Raeva, A. Local adequacy as a design strategy in place-based making. CoDesign 2022, 18, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, A.; Somda, D.; Torino, G.; Irawati, M.; Bathla, N.; Castriota, R.; Vegliò, S.; Chandra, T. Inhabiting the extensions. Dial. Hum. Geog. 2023, 15, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, A.; Raby, F. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Lived Space (Design Context) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Material Perspective (Urban Materiality and Practices) | Conceptual Perspective (Ideas and Meanings) | Dwelling Perspective (Lived Experience) |

| (1) characteristics of urban materiality—built environment, placed in a particular geographical point, characterized by physical manifestations of natural conditions, e.g., temperature, wind, natural light patterns, precipitation—constituting an overall sense of physical comfort and opportunities for performing these daily routines (2) practices—the functions of physical affordances, the order of habits and movements occurring in urban materiality | system of signs, meanings, knowledge, and identities, including individual and social representations, encompassing local spatiality to counteract globalized flows | practical everyday experience of being engaged in a specific built environment, which has distinct material attributes—as sensually/emotionally perceived by a dweller |

| Arctic city context | ||

| modernist architectural environment, where the design of open public spaces and streets for pedestrian activities was not a deliberate aspect of urban planning, led to the lack of all-season scenarios of practices due to the lack of physical comfort | Arctic cities in Russia are referred to as spaces of flows with a diverse mix of cultural attitudes temporarily united by the Arctic space, without the need to assimilate into the original local identity—the culture of the indigenous peoples the dependence on spatial mobility tied to the resource market, alongside broader economic and political contexts, introduces significant uncertainty | the prevalence of modernist “sterile” cityscapes with a monotonous environment leads to the potential negative impacts such spaces may have on an individual’s mental state sensory deprivation and boredom may result from architecture characterized by simple volumetric forms, often lacking meaningful emotional stimuli the overall “cold” visual and sensory qualities of these spaces suggest that urban environments may be perceived as “detached” or “hostile”, which can adversely affect the overall image of the city |

| LSM (urban environment as a design object) as a medium | ||

| the material level of the urban environment both highlights and conceals elements/characteristics of extreme surroundings, influencing comfort levels and affecting the availability of practical features in that space: (1) material characteristics of the urban environment, which mediate physical sensations and enable comfort of everyday practices (mediation of physical affordances) (2) functional content embedded in spatial–technological systems (mediation of practical affordances and habitual routines and routes) | (3) the conceptual level of the urban environment mediates meaning, gathered from the flow of capital, ideas, images, symbols, and technology and embedded in urban materiality this raises the question of what message the built environment conveys to its inhabitants, since this meaning serves as a framework for understanding society’s attitude towards this place | (4) the perceptual level mediates the sense of embodiment through defining relationships between the body and urban materiality, shaping the emotional landscape of a city, experienced through our daily lives. |

| level of LSM adaptation | ||

| (1) protective level (physical affordances as mediation of climatic conditions for creating physical comfort) (2) performative level (functional affordances as a response to human needs) | (3) environment as a material expression of place and local identity, as opposed to global universality | (4) sensual level as an emotional/imaginative content of the environment |

| design system objective | ||

| a harmonious balance between fresh air interaction and physical comfort, achieved through the urban environment where material aspects are adapted and adaptive to all-season practices: (1) comfortable space inviting for interaction (climate comfort as a means of creating incentives to interact with the open space of the city) (2) functionally rich urban experience (seasonally adaptive urban environment, containing diverse affordances for practices) | the foundation of the diverse urban culture of Arctic newcomers developed through the process of design interpretation, showcasing a harmonious integration with the local context and fostering a deeper sense of place; the outcome is the urban environment as a meaningful place (as a tool for forming attachment to a place) | a richly engaging urban experience that adapts to seasonal changes; these elements can serve two purposes: to highlight the transformations in nature—such as enhancing the perception of a wintry landscape with a soft horizon line created by diffused lighting—or to counterbalance these changes, like incorporating the natural hues of a chilly winter dawn into an artificial setting during the polar night the tools for creating emotional imagery include natural light patterns, artificial lighting, the colors and textures of building materials, and elements of the natural landscape like soil, vegetation, and water bodies, as well as the overall spatial arrangement and geometry, etc. |

| context-sensitive analysis | ||

| (1) targeted analyses, using methods in urban climatology, focus on the local urban microclimate and its cyclical changes to select optimal architectural solutions for creating climatic comfort (2) analysis of space utilization to uncover its potential for providing affordances, with the help of structured/unstructured observation, in particular, observational walking and drifting, catching the urban environment as an integrated space, structured and semi structured interviews, and surveys | aligning environmental sensory qualities with conceptual place identity and material characteristics (geography, climate, and existing urban fabric); the primary objective is to examine the local identity through direct methods, such as in-depth interviews, along with systematic literature reviews and discourse analysis to analyze the local socio-cultural, historical, and economic context; also, this could include social media and big data analysis | capturing the ways dwellers sensually perceive the place, in particular, the immediate environment the dwellers’ perspective here is key; thus, in addition to traditional methods like in-depth interviews (which could include associative arrays), it can be useful to refer to mental maps, sense walking, transect walks, and emotional and behavioral mapping |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prokopova, S.; Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S.; Ustyuzhantseva, O. Unfreezing the City: A Systemic Approach to Arctic Urban Comfort. Architecture 2025, 5, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5020027

Prokopova S, Usenyuk-Kravchuk S, Ustyuzhantseva O. Unfreezing the City: A Systemic Approach to Arctic Urban Comfort. Architecture. 2025; 5(2):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5020027

Chicago/Turabian StyleProkopova, Sofia, Svetlana Usenyuk-Kravchuk, and Olga Ustyuzhantseva. 2025. "Unfreezing the City: A Systemic Approach to Arctic Urban Comfort" Architecture 5, no. 2: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5020027

APA StyleProkopova, S., Usenyuk-Kravchuk, S., & Ustyuzhantseva, O. (2025). Unfreezing the City: A Systemic Approach to Arctic Urban Comfort. Architecture, 5(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5020027