1. Introduction

The article begins by examining the contemporary relevance of conceptualizing the façade as a liminal, intermediate space within a building’s exterior, framing it as both a disciplinary and societal issue (Façade Matters in Contemporary Architecture). It situates this concept within prevailing discourses on the architecture and performance of building envelopes, with a particular focus on boundary façade spaces, presenting a state of the art review (Theoretical Insights on the Façade as a Space-Containing Element). The central sections trace the evolution of inhabitable façades in collective housing design, exploring their intersections with concepts of health, privacy, tradition, comfort, and adaptation to place and climate (From the Inside Out: The Expanded Living Spaces of Modern Housing; Regionalism and Modernity: Revisiting the Façade as a Spatial Threshold). This analysis integrates design examples and theoretical insights, spanning twentieth-century architecture, emphasizing critical moments shaped by technological advancements, environmental concerns, and evolving notions of privacy. Finally, this study explores how reimagining external, transitional surfaces in architecture has become a central objective in contemporary collective housing design in Europe (Inhabitable Façades: Integrating Collective Housing with Open Spaces). This section highlights visionary projects redefining façades as threshold spaces that connect, transform, and mediate relationships among adjoining spaces, users, and environments.

The transitional nature of the façade is positioned as a response to growing demands for spatial appropriation, individuality, and climate adaptation. This redefinition fosters, on the one hand, new patterns of collective living and, on the other, new expressions of urban engagement, influencing both the domestic sphere and the city’s image and identity (Discussion). By tracing the evolution of the façade from a surface or skin to an integral spatial and functional component, this study underscores its capacity to operate across scales, reconciling formal and environmental demands while promoting adaptable, sustainable, and engaging living environments.

2. Façade Matters in Contemporary Architecture

The increasing autonomy of the façade in contemporary design is evident in the growing separation between a building’s interior structure and its exterior envelope during conception, design, and construction. Driven by the demands of sustainability, wall construction has become a collaborative domain where architects have ceded significant control [

1]. In the context of collective housing, façades function as shared terrains, engaging architects, façade engineers, material and sustainability experts, horticulturists, and landscape architects. This multidisciplinary approach often results in the building envelope being conceived as an independent layer rather than an integral design component. To counter this trend, the incorporation of intermediate spaces within the building envelope offers a paradigm shift, moving away from hermetic or highly technological envelopes to designs that are more attuned to local climatic and spatial contexts.

Today, façades must balance the tension between exterior form, shaped by the specificities of the context, and environmental performance, driven by interior comfort requirements. This reflects a key challenge in sustainable design, where forms are often more responsive to external environmental factors that internal programmatic demands, diverging from the modernist dictum that “form follows function”, as the “environmental and functional performances of form may be dissociated within the building and allocated to different architectural components” [

2]. The inclusion of interstitial spaces within the envelope addresses this dichotomy, fostering synergies between interior and exterior realms. Such integrations represent a broader phenomenon in contemporary design, enabling radical shifts in architectural expression by extending spatial interactions beyond the envelope itself [

3].

In housing design, façades must prioritize comfort, spatiality, and user engagement, redefining the relationship between inside and outside. The COVID-19 pandemic heightened awareness of intermediate spaces, showcasing their role in enhancing urban living under constrained conditions. Open spaces integrated into the building exterior emerged as essential extensions of living environments, reshaping connections between homes and cities and between individuals and communities. Prevention strategies implemented during this period, both within and beyond buildings, reconceptualized urban spaces as “long, continuous sequence of experimental lab-like settings”, highlighting spatial considerations such as “air circulation, flexible open plan designs, greenery and space for distancing” [

4].

This shift invites a re-thinking of the home, emphasizing its role in fostering a healthy and salubrious atmosphere rather than merely serving as an aesthetically pleasing or functional environment. Architectural elements that mediate between domestic and urban realms, such as balconies [

5], gained renewed significance as adaptable tools for “connecting people, maintaining relationships and mental health, providing us with sunlight and fresh air, and affording a political voice even in isolation” [

6]. During the pandemic, transitional spaces between private apartments and the city in collective housing took on novel, informal, and spontaneous functions, expanding the scope of dwelling beyond the confines of the home [

7]. At the urban scale, these spaces became integral components of broader networks of intermediate environments, further amplifying their importance within established collective housing paradigms [

8].

3. Theoretical Insights on the Façade as a Space-Containing Element

In recent years, a growing body of architectural research has emphasized the evolving nature of the façade [

9], transforming from a solid, opaque enclosure into a complex structural [

10], porous [

11,

12], and interactive [

13] system. This transition is explored through three thematic frameworks, each revealing, illuminating, and expanding on different dimensions of the façade as a space-containing element. The first addresses the façade as an assemblage of components focused on environmental performance rather than mere aesthetics. The second conceptualizes the façade as a thick, articulated, and spatial element. The third examines boundary spaces—such as porches, filters, and thresholds—through a phenomenological lens, focusing on perception, experiential quality, and attunement to place. Together, these frameworks broaden the understanding of façades as both architectural and structural constructs, while addressing their environmental and socio-political dimensions.

The first thematic framework explores the façade as an assemblage of integrated elements that mediate the relationship between interior and exterior, with an emphasis on environmental responsiveness and performance. Alejandro Zaera-Polo and Jeffrey S. Anderson’s

The Ecologies of the Building Envelope introduces the concept of “envelope assemblage”, which describes how various materials and components are synthesized into cohesive systems that adapt to environmental conditions [

14]. These “envelope assemblages” reflect the array of performances the building envelope must sustain in a “temporary state of equilibrium within the conditions of a particular building environment” [

14], shaping their influence on architectural design. Similarly, Randall Korman’s

The Architecture of the Façade explores how façades balance competing pressures from interior and exterior forces—“environmental, technological, or regulatory as well as those that are formal, functional, and aesthetic”—while mediating site, climate, context, and orientation, characterizing them as “subject to various countervailing ‘pressures’ from both sides, requiring varying degrees of negotiation, accommodation, or resistance” [

15]. This perspective positions façades as dynamic interfaces that negotiate the interplay between natural and built environments.

The second framework examines the façade as a thick, articulated, and spatially active element. David Leatherbarrow and Mohsen Mostafavi, in the book

Surface Architecture, argue that the modernist use of the brise-soleil “led to the denial of the frontality of the façade, creating an ‘in-between’ spatiality belonging as much to the inside as to the outside” [

16]. The merging of interior and exterior may also result from design strategies such as overlapping spaces, niches, porticos, terraces, and courtyards, further compressing and activating building envelopes [

17]. Several other studies expand on this notion, interpreting façades as “in-between spaces”, belonging simultaneously to the architectural and urban contexts and thus bridging apparently different, detached, and contradictory worlds [

18]: an “inhabitable architectural threshold, where the cross-pollination of worlds, experiences, and disciplines would find full expression through design and construction” [

19]. And other studies still emphasize the “ensemble of intermediary spaces”, such as balconies, loggias, terraces, and corridors, as “Thick Façade Devices” (TFDs): critical elements in contemporary urban housing, balancing environmental performance with user-centric spatial experiences [

20].

The third framework delves into intermediate spaces embedded within façades, such as porches, filters, and thresholds, focusing on their mediatory and experiential roles. Charlie Hailey, in his book

The Porch: Meditations on the Edge of Nature, emphasizes the symbolic, social, and environmental significance of porches as transitional spaces, charged with renewed agency in the context of ever-shifting environmental conditions, as they foster connections between the public and private, nature and artifice [

21]. As Hailey notes, “the air that wraps a building’s edges, whether or not technically a porch, carries potential: the benefits of public life, the thrills of nature, the atmosphere of weather, the exhilaration of coming and going, the calm of simply sitting down, the warmth of family and friends, and the restfulness of solitude” [

21].

Michel Guitart, in

Behind Architectural Filters: Phenomena of Transference, expands this discussion, conceptualizing architectural filters as relational mechanisms that mediate spatial and perceptual dynamics [

22]. “An architectural filter”, Guitart writes, “whether it is a thin translucent skin or a heavy structure—placed between the outside and the inside performs as a mediating mechanism that channels perception” [

22]. Guitart highlights how filters, whether material or symbolic, transform interactions between interior and exterior realms, enriching architectural experiences through their inherent and expressive qualities. In addition, they hold a key role in fostering relationships: rather than merely serving as tools for delimitation or facilitating physical transition, visually and conceptually, their primary agency is to offer a space for relational engagement [

22].

A broader theoretical emphasis on thresholds complements these studies, pointing to their evolution from concrete architectural elements, signifying entrance and transition, to dynamic conceptual tools in architectural design [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Till Boettger, in

Threshold Spaces. Transitions in Architecture, introduces the notion of “threshold space” advocates for thresholds as critical design elements that enhance spatial transitions and deepen architectural immersion [

29]. Laurence Kimmel, in

Architecture of Threshold Spaces, explores thresholds as both social and political constructs, which function in relation to the “dialectics of public space”, reflecting and shaping their environments [

30]. Kimmel discusses how “every singular architecture challenges visitors to negotiate their movement and activity in a specific way” especially in connection to the threshold [

30]. These studies underscore the façade’s role in negotiating architecture’s dual capacity to respond to environmental conditions and foster socio-spatial relationships [

30].

4. From the Inside out: The Expanded Living Spaces of Modern Housing

Modern Movement residential projects revised the character of architectural boundaries, transforming collective housing façades into articulated, inhabited, and porous envelopes. Early concerns about integrating buildings with their natural environments informed this transformation. Articulating his dictum “the outside is always an inside”, Le Corbusier observed that architecture inherently interacts with its environment: “the air around [a building] constitutes other surfaces, other grounds, other ceilings. […] The surroundings envelope me in their totality as a room” [

31]. Although his writings offer only sporadic definitions of the “threshold”, they underscore a key architectural relationship: “L’extérieur est le resultant d’un intérieur [The exterior is the result of an interior]” and “Le dehors est toujours un dedans [The outside is always an inside]” [

32,

33].

The view of the façade from within evolved as a key motif in the photographic documentation of modern domestic spaces. Interior perspectives of the duplex apartments in Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille (1945–1952) (

Figure 1), such as those captured in the photographs of René Burri and Lucien Hervé, underscore this spatial continuity. The double-height loggia, serving as an extended living space, along with multiple vantage points towards the exterior, encapsulated the project’s housing vision. The aggregation of apartments around the “interior streets” ensured direct connections to natural elements: “The long apartments cut down the strong Mediterranean sun, give cross-ventilation and provide a variety of new spatial experience[s]” [

34]. This project concretized earlier experiments in hybridizing domestic spaces with nature and open environments, such as the Immeubles-Villas project (1920s–1940s), the Honeycomb Housing for Ville Contemporaine (1922), and the housing units at Pessac (1923) [

35]. The Immeubles-Villas project, in particular, embodied the concept of architecture as a “breathing machine” [

36], incorporating hanging gardens into the façade.

The open-air room became a defining feature of modernist collective housing, influenced by modern healthcare architecture, notably sanatoriums, where exposure to light and fresh air was deemed essential for the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis [

37]. The “deep sun terrace” became a hallmark of sanatoria architecture, alongside elements such as “balconies, covered corridors and garden shelters which were furnished with reclining sofas for the jour médical” [

38]. Photographic representations further highlighted these blurred boundaries between interior and exterior. For instance, an image from inside a ward in Richard Döcker’s Waiblingen Sanatorium (1929), featured in Sigfried Giedion’s book

Befreites Wohnen. Licht, Luft, Öffnung [Liberated Dwelling: Light, Air, Openness] (1929), emphasized the architectural aim of dissolving distinctions between inside and outside (

Figure 2). This photograph connects to another on the book’s cover, taken by Carlo Hubacher, depicting the view from the living room of one of Max Ernst Häfeli’s Rotach-Häuser (1928) in Zurich (

Figure 2). The image draws attention to the depth of the building envelope, directing the viewer’s gaze outward, past the ample glass doors, the balcony space, the mesh railing, and the riverscape in the distance [

39].

Modernist interiors, often captured in black-and-white photography, illustrate a reciprocal relationship between the building’s interior and the external realms of landscape, weather, and the environment. This interplay extended domestic spaces outward, addressing both aesthetic and functional concerns, including environmental qualities and human well-being. Collective housing projects of the Modern Movement exemplified a spatial condition where interiority and exteriority coexisted.

This evolution had two key implications. First, it demonstrated how “the roots of sustainability were always present in modern architecture”, though often manifested as fragments addressing material efficiency, climatic responsiveness, and integration of green spaces within cities [

40]. While abstraction and aesthetic simplicity characterized modernist designs, a parallel focus on environmental performance informed emerging approaches to architectural functionalism [

41]. Early twentieth-century concerns with public health, hygiene, and human well-being [

42] also shaped this integration of buildings with their surroundings, particularly through the articulation of the façade. Second, it underscored the growing “publicity of the private” [

43], reflecting changing notions of privacy and their spatial consequences in the domestic sphere. As Beatriz Colomina observes, modernity introduced a shift in the relationship between inside and outside: “a displacement of the traditional sense of an inside, an enclosed space, established in clear opposition to an outside” [

43]. The incorporation of inhabitable open spaces within the building envelope mirrored the characteristics of urban public spaces—specifically, the realm of the street—fostering “subjectivity, individuality, and interiority” [

44]. As Richard Sennett suggests, metropolitan subjects were “capable of observing complex external conditions and harbouring quite distinct thoughts simultaneously” [

45]. This duality underscores how the integration of inhabitable open spaces within the domestic realm not only redefined spatial boundaries but also fostered new modes of interaction and coexistence, blurring the lines between private introspection and public engagement.

5. Regionalism and Modernity: Revisiting the Façade as a Spatial Threshold

The redefinition of liminal spaces between buildings and their surrounding environments reached a peak in the second half of the twentieth century, when architectural practices, guided by climate-specific considerations, “encouraged inhabitants to interact differently with their façades and the spaces those façades helped produce, thereby activating a new relationship between inside and outside, and hence between societies and environments” [

46]. New façade typologies emerged alongside innovative approaches to thermal comfort, physiological perception, and human well-being. These approaches, evolving systematically from the 1950s onward, gave rise to “new subjects—new individuals with novel desires, newly sensitive to the thermal conditions of the interior” [

46]. This experimentation in façade design and climate control signaled a paradigm shift in architecture: buildings were no longer perceived as objects that could be transplanted independent of their geographical and climatic context, but as complex architectural systems intrinsically linked to their territories.

Attention was directed towards the environmental dimension of architecture, addressing issues of tradition, place-specificity, and a “physical aesthetic”—a perceptual and physiological experience of built space grounded in its environmental qualities, rather than solely visual perception [

47]. Collective housing projects from the 1950s and 1960s that explicitly engaged with the environment can be understood within a theoretical framework of regionalism and the re-appraisal of vernacular, spontaneous, and anonymous structures. These projects sought to establish new connections between modern architecture and regional appropriation, as “the emergence of modern architecture also depended on a host of complicated interrelationships with the vernacular and the traditional as cultural patterns purportedly inferior to those that followed” [

46]. Elements from regional vernacular architecture, including built forms and climate-control devices, were integrated into modern designs, enriching the architectural response to its context.

In the 1950s, several architectural writings emphasized the importance of vernacular architecture as a source of inspiration for modern design. Paul Rudolph, in his article “Regionalism in Architecture”, argued that elements found throughout the global South, such as verandas, porches, patios, loggias, exterior circulation corridors, and sun-control devices, “should find new expression” in modern buildings [

48] (

Figure 3), citing projects such as Erich Mendelsohn’s Maimonides Hospital in San Francisco (1946–1950) and Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s renovated Cité de Refuge building in Paris (1929–1933; 1948–1952). This perspective aligns with the observations made by Gio Ponti in his 1928 article for

Domus, where he highlighted the “uncomplicated” relationship between interior and exterior, buildings and gardens, in Italian architecture, facilitated by terraces, verandas, loggias, balconies, belvederes, and pergolas—elements designed to create “a comfortable and pleasant domestic atmosphere” [

49].

As Michelangelo Sabatino has observed, the presence of vernacular architecture has continuously influenced modernist output in Italy, likening it to “an underground river that meanders through the crevices of the bedrock, only to surface occasionally and disappear once again” [

50]. This connection is particularly evident in elements designed to mediate the relationship between the inside and the outside, drawing from Mediterranean traditions. Similarly, Nicole Eleb Harlé has pointed out that inhabiting intermediate spaces between the house and the city is an inherent phenomenon in Mediterranean countries, carrying gendered connotations and demonstrating how “customs are differentiated not merely by contrasting cultures, but also by lifestyles” [

51].

James Stirling echoed this appreciation of vernacular traditions, referencing the influence of “the plastique of folk and anonymous architecture”, which was particularly stimulated by Mediterranean building practices [

52]. He acknowledged that regionalism emerged as architects sought to reappropriate built forms from vernacular traditions. This line of thinking also resonated with Sigfried Giedion’s article “The New Regional Approach”, in which he discussed the growing shift in architectural attitudes towards integrating the environment and regional context into the modern design project [

53]. Giedion emphasized that architects, when faced with the challenge of building in underdeveloped areas, sought “to translate the continuity of long-established habits of life into terms of contemporary architecture” [

53].

Post-war theoretical inquiries into new intersections between architectural design, tradition, and ecological concepts introduced the notion of the “in-between” as a compelling reference. The chapter “Grouping of dwellings” in the

Team 10 Primer (1968) provides the example of housing models for Morocco (1951–1952) by ATBAT-Afrique, which sought to transpose the patio space—a defining feature of traditional Moroccan dwellings—into the context of multi-story housing. This approach aimed to introduce liminal spaces “flooded with sun” while facilitating access to different apartments [

54] (

Figure 4). A shift in the appreciation of liminal and transitional architectural spaces is evident: whereas “nineteenth century reformers perceived shared stairwells and galleries as compromises, for the modernists, these were signs of efficiency and collectivity” [

55].

The

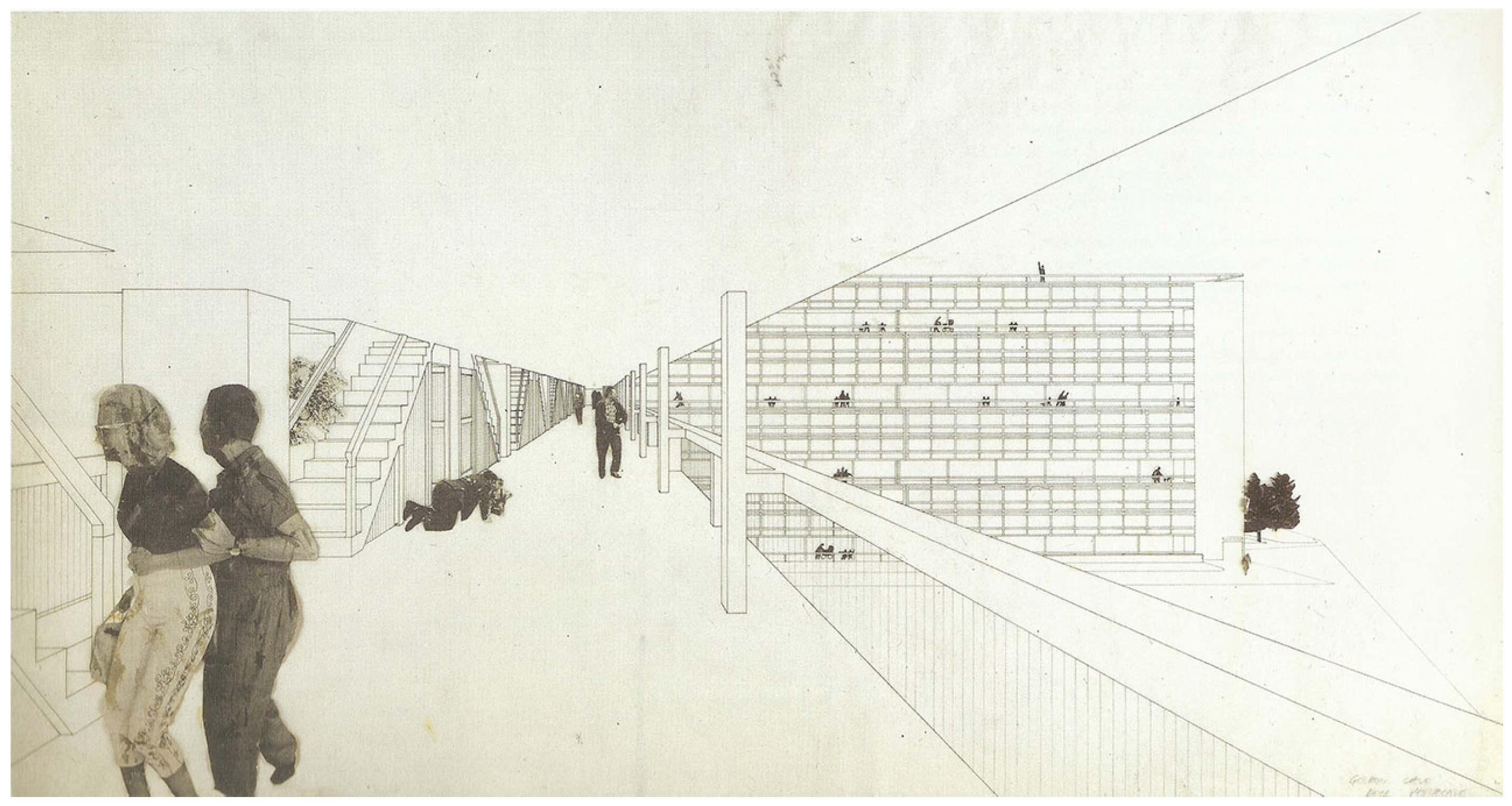

Team 10 Primer’s exploration of collective housing, aimed at “re-identifying man with his environment (contenu et contenant)”, is evident in projects like the Golden Lane Deck Housing competition entry by Alison and Peter Smithson (

Figure 4). This project incorporated spatial elements and concepts inherent to the city, seeking new connections between domestic and urban realms. These explorations emphasized the importance of creating “effective group-spaces fulfilling the vital function of identification and enclosure making the socially vital life-of-the-streets possible” [

54]. They underscored that “it was at the threshold, at points of interconnection, that architecture could restore continuity to the fragmented urban experience in which the experience of community was torn asunder” [

56].

Façade design, from the standpoint of regionalism, was systematically addressed in Victor Olgyay’s

Design with Climate. Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism. Olgyay argued that “architectural expression must be preceded by a study of the variables in climate, biology, and technology” [

57] present at a given location, as human dwellings and architectural forms are holistically shaped by sociocultural, historical, and climatic influences (

Figure 5). The façade design projects included in the “Solar Control” chapter, among them SOM’s Lever House in New York (1951–1952), Harrison & Abramovitz’s, Republic National Bank Building in Dallas (1949–1954) and Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille (1945–1952), pointed to the transition of the façade from the massive load-bearing wall to the building skin. A part of them drew on biological principles and vernacular architecture examples across different climate zones, offering an ecological perspective on modern design. These examples were integral to the book’s hypothesis: achieving an efficient balance between context and architecture is possible, much like the thermal adaptation of the human body [

58]. They served as visual evidence of methods for considering climate across different zones, reducing the distinctions between interior and exterior climates through structural and architectural tools.

These writings foreshadowed a growing interest in vernacular architecture, which found expression in publications such as Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s

Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture (1957) [

59], Bernard Rudofsky’s

Architecture without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture (1964) [

60], and Myron Goldfinger’s

Villages in the Sun: Mediterranean Community Architecture (1969) [

61]. The appreciation of vernacular architecture became a cornerstone for modern architects aiming to create regionally sensitive, climate-responsive, and culturally grounded housing designs.

Several apartment buildings of this era were conceived from the inside out, prioritizing the perspective of the inhabitant and the creation of new spatial experiences in domestic contexts. For example, José Antonio Coderch’s Casa de la Marina apartment building (1952–1954) integrated inhabitable private open spaces in the form of loggias with varying depths. These spaces maintained the impression of a continuous envelope while providing a functional and aesthetic connection to the exterior (

Figure 6). Coderch’s design drew inspiration from regional vernacular architecture, particularly the use of horizontal shutters combined with large horizontal slabs [

62]. Similarly, Lionel Mirabaud and Jean Prouvé’s apartment building on Mozart Square in Paris (1953–1954) featured a solid volume with a stratified façade composed of glass and manually operated sliding or folding aluminum panels (

Figure 6). These panels allowed for diverse qualities of natural light and ventilation, offering adaptability that a continuous glazed façade could not achieve. Asnago and Vender’s residential and commercial building on Viale Caterina in Milan (1958–1964) incorporated a continuous brise-soleil screen, originally crafted from wood, that extended along the entire height of the façade and concealed the apartment balconies (

Figure 6). In all three cases, the design project balanced functionality with aesthetic intent by integrating solar control elements and open or semi-open inhabitable spaces into the building exterior. These features invited users to actively engage with and appropriate the architectural façade, creating dynamic and adaptable exteriors, responsive to climatic, spatial and functional needs.

As environmental challenges intensified, architecture sought to reconcile human habitation with the natural environment in urbanized contexts, adapting designs to the specific characteristics of each region. This effort was reflected in late twentieth century theories. With the framework of Critical Regionalism, Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre argued that “problem-solving should de-empathize imported universal solutions in favor of reflective, local and unique qualities of a region” [

63].

Building on this perspective, Kenneth Frampton called for an architecture that overcomes placelessness and lack of identity by responding to a building’s geographical context [

64]. According to Frampton, “what is evident in the case of topography applies to a similar degree in the case of an existing urban fabric, and the same can be claimed for the contingencies of climate and the temporally inflected qualities of local light” [

64]. In particular, he asserted that the modulation and incorporation of sun and climate control factors in design should be “fundamentally opposed to the optimum use of universal technique” [

64]. This emphasis on climate adaptation in design laid the groundwork for viewing the architectural envelope as an articulated, layered, and porous surface, influencing new approaches to materiality, tectonics, and expression.

During this period, a particular stream of inquiry emerged around the relationship between buildings and their context, focusing on intermediate spaces. For Robert Geddes, transitional, interstitial, and liminal spaces drew inspiration from the spatial qualities of a clearing, with the forest edge representing both “man’s ideal habitat and as a mythical image” [

65]. He proposed that architectural design should recreate such intermediate conditions between natural and artificial environments [

66] through elements like “arcades and colonnades, loggias and porches, thresholds, cloisters, courtyards and peristyles” [

65] as models for both shelter and openness, pointing to their potential to generate new architectural concepts and spatial forms.

Connections between architecture and the natural environment—this time in the literal sense of nature—were also explored in theories of biophilia that emerged during the same period, drawing upon Erich Fromm’s initial interpretation of the term. Biophilia, embraced by theorists across various fields, including architecture and urban planning, has served as a tool to explore ways of bringing “the beneficial experience of nature into the design of contemporary buildings, landscapes, communities, and cities” [

67] while aligning design with the fundamental human instinct for survival and deep-rooted affinity for life and natural processes [

68].

Drawing on these theoretical explorations, façade design began to focus on sustainability during the 1980s, emphasizing the energetic interplay between indoor and outdoor environments. This approach prioritized vernacular forms and mediating envelopes that balanced opacity, resistance, transparency, and porosity, while integrating technological advances. Visionary projects from this period underscored the diverse functions, meanings, and narratives façades could bear in collective housing: as a service-containing layer, an additional inhabitable space, an active climatic band, and a structure for vegetation and landscaped areas. This evolution set the stage for contemporary architectural practices, focused on spatial continuity, appropriation, and climate adaptation, redefining the architectural boundary.

6. Inhabitable Façades: Integrating Collective Housing with Open Spaces

Contemporary residential architecture increasingly emphasizes the integration of open spaces within collective housing at both building and apartment scales. Intermediate, liminal, and transitional spaces embody a new vision for urban collective living [

69] that is both socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable. Despite this growing focus, the role of such spaces in design has been only partially explored in recent collective housing design manuals.

In

Housing Design: A Manual (2012), the concept of building “skin” is reconceptualized in the Tectonics chapter, moving beyond the traditional understanding of façade as “a single layer” or “a complex package with inner and outer cladding” and toward its definition as “a complex spatial system in which physical and spatial dividing lines do not coincide” [

70]. Similarly, in

Holistic Housing (2012), spatial quality is assessed through elements such as “private open spaces” and the “relationship between indoor and outdoor areas”, while positive design attributes include placing living rooms in well-lit zones with connections to outdoor spaces, like balconies or gardens [

71]. Meanwhile,

Floor Plan Manual Housing (2017) explores the role of “complex access systems” where multiple entry points and pathways transcend conventional single-entry designs, thereby integrating these spaces into the building’s hierarchy and projecting “access cores openly into the cityscape” [

72]. However, the full potential of these spaces in mediating various orders, qualities, and interests remains underexplored.

The space-containing façade offers a departure from the modernist tradition of all-glass building envelopes, which catered to the fantasy of transparency, thinness, and malleability. Instead, it introduces “complex cuts in the façade that incorporate in-between spaces, establishing porous boundaries and screened-off zones through the use of membranes, screens, filters, and latticed grilles, which create spatial and perceptual distance between the observer and the building [

73]. Such transitional spaces transform façades into permeable boundaries that connect domestic interiors with natural elements, such as sunlight and fresh air, crafting a habitat within the relationships the dwelling forms with these elements [

74]. This approach not only enriches the architectural experience but also fosters environmental sustainability.

From an urban perspective, these façade elements redefine the monolithic building volume not through solid mass but through sliding, mobile, and adaptable elements. These features reconstruct urban blocks by fostering continuity between adjacent building façades (Eduardo Souto de Moura, Apartment Block at Rua do Teatro, Porto, 1995) and differentiating their relationships with surrounding urban or landscaped contexts (Herzog & de Meuron, Apartment and Commercial Building Schützenmattstrasse, Basel, 1992–1993; Herzog & de Meuron, Rue des Suisses Apartment Buildings, Paris, 1999–2000).

In certain instances, glass panels create dynamic façades that absorb and reflect their immediate surroundings, changing appearance with the time of day or the seasons, offering a variety of visual impressions (Baumschlager and Eberle, Wohnanlage Eichgut, Winterthur, 2002–2005; Annette Gigon, Mike Guyer, Housing Development Brunnenhof, 2004–2007; Guillermo Vásquez Consuegra, Social Housing, Vallecas, Madrid, 2017) (

Figure 7). As Mirko Zardini notes, these façades transcend the traditional boundary of the façade as a static element, becoming spaces that both absorb and project the building’s interior and exterior [

75]. The mutable qualities of these surfaces introduce a new visual language, characterized by varying densities, porosities, and opacities.

In other instances, the façade adopts a woven texture, echoing Gottfried Semper’s theory that the origins of architecture lie in textile elements that serve as separating devices (Baumschlager and Eberle, Residential Building Mitterweg, Innsbruck, 1996–1997; David Chipperfield, Ninetree Village, Hangzhou, China, 2004–2008; FOA Architecture, 88 Social Housing, Carabanchel, Madrid, 2006). These surfaces evoke the sensory qualities of materials shaped by human craftsmanship, inviting a perceptual experience that extends beyond intellectual reflection [

76] (

Figure 8).

Space-containing façades also offer passive climate control alternatives to sealed, insulated envelopes and mechanically regulated interiors. These façades evolve into stratified systems, integrating thermal curtains, polycarbonate panels, textile shutters, and semi-open spaces like balconies, loggias, and winter gardens which function as “an intermediate, indeterminate and informal place”, providing opportunities for “imagining a new future of domestic space” [

77]. The incorporation of voids or exterior space as integral components of the building composition further supports this approach (Kazuyo Sejima, Kitagata Apartment Building in Gifu, 1994–1998; RipollTizon Estudio de Arquitectura, Social Housing in Ibiza, Ibiza, 2022).

Furthermore, the management of integrated sun-shading systems, which are part of a broader range of sustainable façade materials, encourages inhabitants to become “active participants in the care of their building [and] their quality of life” [

78] (MAIO, Social Housing, Sant Feliu de Llobregat, 2024; Studio Muoto, Dwellings, Nursery and Emergency Shelter, Paris, 2017; LAN Architecture, 79 Collective Housing Units, Bègles, 2015) (

Figure 9). These systems play a crucial role in determining energy consumption and enhancing the environmental quality of interior spaces.

Space-containing façades also reflect evolving notions of privacy in contemporary residential culture. The growing emphasis on collective living challenges the individualistic focus on privacy by addressing societal challenges through an expanded number of shared spaces, as “individuals sacrifice some level of privacy in exchange for community” [

55]. The tension between privacy and publicness has been critically reexamined, with privacy now understood as both a social and architectural construct, rendering it a fertile ground for creative interpretation [

44]. Consequently, in numerous recent collective housing projects, the fulcrum of communal life often shifts to the building’s liminal spaces (Dreier Frenzel Architecture, Cooperative Housing Association Apartment Building, Ecoquartier Jonction, Geneva, 2017; EM2N, New Housing on Briesestrasse, Berlin, 2020; Esch Sintzel Architekten, Housing Development Maiengasse, Basel, 2023) (

Figure 10).

These neutral, programmatically undefined spaces—such as thresholds, galleries, and terraces—carry urban connotations and enable varying degrees of privacy and public interaction. They balance contemplation and socialization, retreat and exchange, while expressing towards the exterior the nuanced character of high-density urban living. From the building entrance to the apartment door, “the multiple gradual thresholds are opportunities to socialize, subtle interposed barriers of a less mundane spatiality, spaces where plants can grow uncommonly tall; corners hidden and indifferent to their interior-exterior duality” [

79]. These interstitial spaces foster a sense of community and enrich the urban fabric through layers of interaction and identity.

7. Discussion

The integration of open and transitional spaces in collective housing represents a significant shift towards more adaptable spatial environments. This shift highlights the façade as a crucial, multifaceted, and dynamic interface that mediates relationships between interior and exterior, nature and artifice, private and collective realms. The space-containing façade has emerged as a complex yet powerful concept in architectural design, encompassing conceptual, spatial, functional, aesthetic, symbolic, and political dimensions. As collective housing models continue to evolve, the dynamic interplay between buildings, environments, and users remains a critical area of exploration, requiring a deeper understanding of how we define, experience, and inhabit liminal spaces in architecture.

Incorporating intermediate spaces as integral elements of façade design creates new interactions between inhabitants, buildings, and their surroundings. By approaching the multi-story collective housing façade as a space-containing entity—stratified, articulated, dynamic, and adaptable—the aesthetic perception of collective urban housing is expanded while linking it to sustainable performance. This approach reframes our understanding of the built environment in relation to the natural world [

80].

The design of collective housing façades must transcend mere quantitative or functional metrics to encompass aspects of perception, experience, and social interaction. This shift underscores the need to rethink concepts such as utility, efficiency, comfort, and the social narratives of well-being in relation to spatiality and the domestic sphere [

77]. Emerging housing models in collective living offer opportunities to improve sustainable performance through a holistic approach that integrates “climate targets, a just distribution of housing resources and the role of community” [

81].

Designing the façade as a space-containing element establishes new connections between domestic spaces and the city. Communal façade spaces become part of a broader network of transitional spaces, transforming previously void or static areas into dynamic environments that encourage change, social participation, and engagement, while enhancing urban porosity. These in-between spaces hold the potential for urban regeneration, extending the spatial and functional definitions of ground-floor areas shared between urban and residential domains [

82]. They bridge architectural and urban scales, blending interiority with urbanism and highlighting that “any act of architecture is an act of urbanism in terms of the system of relationships, proximities, juxtapositions and superimpositions it generates” [

83].

Ultimately, inhabited façades play a central role in promoting flexibility, modification, and freedom of use, creating a sense of identity, and belonging within urban living. It underscores that “the building is its effects and is known primarily through them, through its actions or performances”, which are dependent on occurrences such as the interests and practices of its inhabitants, climate, seasons, and time of day [

17]. Panels of variable transparency, shifting positions, and changing luminosities—juxtaposed, superimposed, and transposed on static surfaces—generate a dynamic, ever-evolving character in the urban landscape, reminiscent of the fluid nature of windows on digital screens.