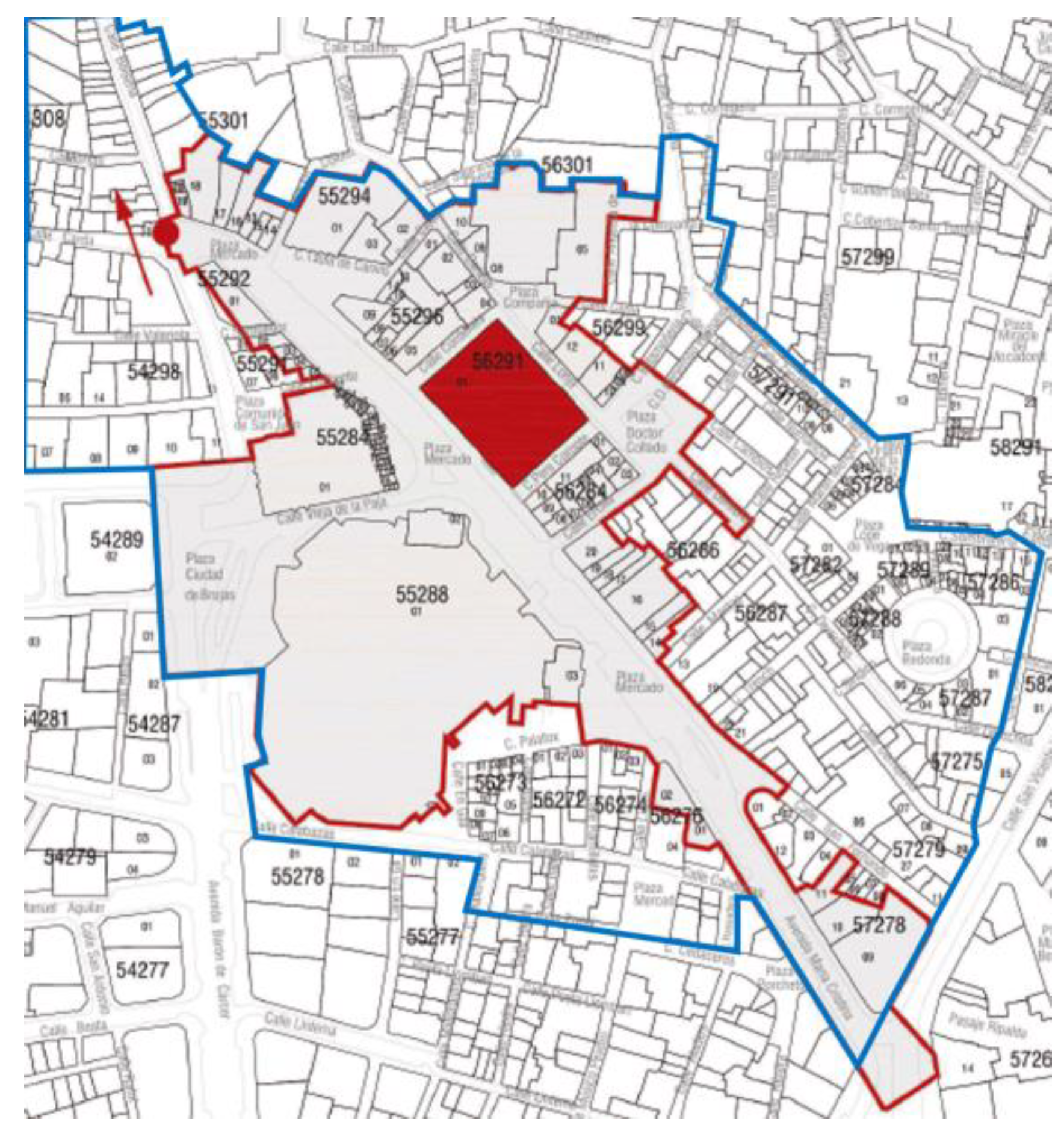

In legal terms, the Special Plan for the Ciutat Vella district (passed in February 2020) outlines a perimeter for the surroundings of the Lonja, considered an asset of cultural interest (see fiche C1-13 from the Protection Catalogue; [

29]). This perimeter (

Figure 4) includes notable buildings such as the Lonja and the adjacent Consulate of the Sea (

Figure 4b(a)), Mercado Central or Central Market (

Figure 4b(b)), and churches such as those of Santos Juanes (

Figure 4b(c)) and Sagrado Corazón de Jesús de la Compañía or Jesuitical church (

Figure 4b(d)); public spaces such as the squares of Mercado (

Figure 4b(e)), Collado (

Figure 4b(f)), Ciudad de Brujas (

Figure 4b(g)), of la Compañía (

Figure 4b(h)) and some streets and avenues such as María Cristina avenue, and the streets of Taula de Canvis, Cajeros, Danzas, de la Lonja, Pere Compte, Ercilla, Derechos, Vieja de la Paja, Sampedor; as well as the dwellings and buildings included in or adjoining this perimeter.

2.1. The Market Square

The Plaza del Mercado or market square in Valencia is an outstanding example of the urban geographical inertia of a function, in this case, the buying and selling of foodstuffs and objects. This is not unlike the inertia of the position of a religious building within a city. As the centuries pass, the container for a function can be replaced or transformed but the activity remains. This is what has happened with the site of Valencia Cathedral, which was previously a mosque, before that a Visigoth basilica, and initially, a Roman temple. The market square has been fulfilling the same function for at least a thousand years.

The market square is without doubt one of the most important elements of the surroundings of the Lonja: a space among buildings that is empty, yet always full of activity and people. Over centuries this square has been shaped and gradually transformed thanks to the new forms of design observed in cities and public spaces, as well as different historical developments and new demands. The market square was defined fundamentally during the Middle Ages, based on the profile of the Moorish town wall on its northeast side. The area occupied by the square has never had a clear and precise geometry. Its outline is the result of the construction of buildings that throughout history have progressively drawn these limits: the churches and convents, the markets, the Lonja and the buildings with shops and dwellings. Therefore, the form and dimension of this square have depended more on its outer limits than on the space itself and, as a result, both its shape and surface have changed over time.

The space currently occupied by the market square was originally outside the walls of the Islamic city of Balansiya (

arrabal of Boatella), between the Gate of Boatella (

Bab al-Baytala) and the Gate of the Alcaicería (

Bab al-Qaysariya). The Gate of Boatella must have been one of the main accesses to Balansiya, used for the passage of goods. Furthermore, near the Gate of the Alcaicería there was market activity, both inside and outside the city walls ([

18], p. 425). The market area in the city of Balansiya could therefore be said to have been consolidated after the city’s conquest by Jaime I in 1238 and was in the area once occupied by the market of the Islamic city. Outside the wall, opposite the Gate of Boatella, was the

arrabal of Boatella, a small rural settlement near a large necropolis dating to late antiquity [

19]. This

arrabal, made up of houses inhabited at the time of the conquest of Jaume I and referenced in the

Llibre del Repartiment, may have been walled, with two accesses, as gleaned from the information from Barceló [

15].

Although in the Islamic era, there was already a space outside the walls used as a market, the consolidation and development process began in the Middle Ages, when the space outside the walls was taken over through the construction of convents, the incorporation of the

arrabales and the foundation of the

pueblas (medieval urban settlements), which gradually formed the outer perimeter of what later became a medieval city delimited by walls erected throughout the 14th century [

30]. This process of progressive colonisation of the territory surrounding the medina led to the definition of the market square through the gradual construction of a number of religious buildings. The foundation in 1240 of the Convent of La Merced ([

8], p. 72) was followed by that of the Convent of Santa María Magdalena, and the establishment in 1268 of the former hermitage of Santos Juanes. This space delimited by religious buildings to the southwest and by the Islamic wall to the northeast was gradually incorporated into the medieval city, where increasingly bustling temporary and permanent shops could be found in the triangular area, while artisans and workshops tended to be located on the perimeter. The construction of the new medieval wall and the sizeable expansion of the urban area meant that the market square remained within the geometrical centre of the city.

On the night of 16 March 1447, for a full seven hours, a fire raged through almost two hectares of houses on a corner of the market square. This event was recently studied in depth to document information relevant to the history of this part of the city [

31]. The fire, which was probably started as revenge for an execution that had taken place in the same square days earlier, destroyed 46 houses and the fish stalls of the market and resulted in the death of 10 people. According to reports at the time, the fire completely destroyed the carpentry workshop as well as the buildings from the cemetery of Santa Catalina to Puerta Nova, and from El Trenc to the poultry and fish sellers. As Jaume Roig ([

16], p. 77) put it at the time: “…La Pellería, Trench-Fusteria, Fins mig mercat, Nas vist cremat.”

The number of people receiving damages for the destruction caused by the fire provides a very vivid picture of the range of artisan activities occurring in this district—and so near the market square: carpenters (the guild most affected by the fire), merchants of wool fabric, spices or second-hand clothes, bakers, cobblers, ironmongers, tailors, painters, cheesemakers, box manufacturers, haberdasheries, etc. Furthermore, following the extensive fire damage to the buildings, a plan for urban regularisation was implemented to rectify the existing streets and restructure the area ([

31], p. 514). No images of Valencia at this time are conserved, but it is apparent that these works to straighten the streets around the square aimed to improve and consolidate a part of the city that was gaining importance and becoming increasingly representative, a status finally cemented between 1482 and 1548 with the construction of the new Lonja de la Seda.

Valencian humanist Juan Luis Vives (1492–1540), who lived in the city until 1509 and knew the market square, was able to see the completed Contract Hall of the Lonja and the adjacent Consulate of the Sea under construction. Away from his family and city, through his literary alter ego Centelles, he said: “What a large market! What excellent order and distribution of sellers and goods! The scent of these fruits! The variety! What beauty and cleanliness! No orchards can compare to those that supply this city, nor is there diligence to equal that of the market inspection and his ministers so that buyers are not deceived …” ([

32], p. 356).

The first existing view of Valencia is that drawn by Anthoine Van Den Wijngaerde (1512/1525–1571) in 1563 [

20]. This view shows—albeit unclearly—the market square and the surrounding representative buildings: the religious building on the left, with the lettering “Madalena”, is the convent of Santa María Magdalena; in the centre, the caption “Logia” refers to the space at the back of the Lonja de la Seda, possibly as a way to distinguish between the Lonja de la Seda and the Lonja del Aceite (Oil Exchange), which may be the building bearing the same lettering and seen on the left; on the far left, with the caption “S. Joan” we find the church of Santos Juanes; in the centre of the square the author draws a structure that is identified as the gallows ([

8], p. 93).

On the plan drawn up by Antonio Mancelli (?–1645) in 1608, in the perimeter of the market square we see the notable buildings of the Lonja de la Seda (

Figure 6a(1), the church of Santos Juanes and the convents of La Merced and Santa María Magdalena. Behind the Lonja de la Seda, Mancelli draws attention to the Lonja del Aceite (

Figure 6a(2). Mancelli’s plan shows the market square as a vast empty space with a gallows in the centre which brings to mind the public executions which took place there. The simple profile of the church of Santos Juanes (

Figure 6a(3) is highlighted as it shows the church prior to the remodelling work, which resulted in the new church façade looking onto the market square, as seen in the 1704 plan by Father Tosca. However, the church depicted by Mancelli does not blend in with the square and appears completely disconnected from it, despite helping to define the northwest limit. Nevertheless, the edge of the square appears to be delimited by the notable buildings, especially by residential ones, which are anonymous, and follow the same model of ground floor access and first-floor windows. The author provides a clear simplified representation showing the same pattern of residential buildings that is repeated on every plot: a ground floor door and two first-floor windows.

The following plan of the city of Valencia was drawn by Father Vicente Tosca (1651–1723) in 1704, almost a century after Mancelli’s (1608). On Tosca’s plan, and in the updated version by José Fortea (1738), it is possible to see the transformations undergone by the market square in the 17th century, a topic widely studied by García Peris ([

8], pp. 113–154): the construction of the chapel of Communion of the church of Santos Juanes (1643) (

Figure 6b(4); the reconstruction of several collapsed houses in different parts of the square (1663–1666); the addition of the fountain by Juan Bautista Pérez Castiel (1650–1707) in the centre of the square (1672), which remained there until it was replaced by a larger one (

Figure 6b(5); the consolidation of the church of La Merced and the remodelling of the cloister (both completed in 1662), as well as the completed construction of the bell tower (finished in 1670) (

Figure 6b(6); the demolition of the old church of the convent of Santa María Magdalena (1636) and the construction of the new church (completed in 1679) (

Figure 6b(7); the Baroque updates to the church of Santos Juanes and the construction of the façade depicting scenes towards the square (1693–1702), including the construction of the podium which hosted

les covetes (commercial premises) (

Figure 6b(3)—expanded in 1713 to surround the chapel of Communion—thus creating 19 premises for vendors (seen on the 1738 plan). Finally, the appearance of porticoes on the different façades of the blocks that look onto the square should also be noted (

Figure 6b(8)) on the buildings adjoining the convent of La Merced, on the two blocks between the convent of Santa María Magdalena and the church of Santos Juanes, as well as on the block found beside the chapel of Communion of the church of Santos Juanes.

In addition, the ground floors of the buildings around the square are shown on 18th century plans with continuous doors which never fully become porches but serve as shop windows for businesses. The porticoes of the market square are shown on several occasions throughout the 19th century on plans and in views by different authors. In the “Plano geométrico de la plaza de Valencia y sus contornos” by Francisco Cortés y Chacón 1811 ([

14], p. 44–45) the buildings with porticoes on either side in the market square are marked. These can also be seen in the view by Laborde around that time, as well as in later ones such as that by Aulaire in 1830 ([

21], pp. 130–131).

After the confiscation of Mendizábal (1836), the market square was modified extensively following the demolitions of the convents on the southern limits of this urban space: the convent of La Merced and the convent of Santa María Magdalena. In 1839, the site formerly occupied by the latter saw the inauguration of a new market called Mercado Nuevo or Mercado de los Pórticos (new or porticoed market). The plot of land that had housed the demolished convent of La Merced was used for the construction of dwellings, which replaced both the convent and the housing with porticoes that had closed off the square on its south border.

These construction projects marked the start of a progressive modification of the urban space which could be described as “from the square to the street” (

Figure 7), the empty space by the market buildings was gradually occupied, first by the porticoed market (

Figure 7b) and later by the central market, as well as housing. With the construction of the central market (

Figure 7c), the market square was reduced to a series of expansions on a single street, taken up for some time by the traffic from carriages, the passing trams and vehicle traffic (

Figure 7d). These almost residual triangular spaces completely blurred the concept and use of the former square, which had become unnecessary from the moment the market stalls were relocated to the central market. In this respect, it should be stressed that the project by the architects Peñín and Quintana [

33] envisages the pedestrianisation of the market square and a more homogeneous and dignified treatment of this setting, which had gradually deteriorated, and clearly required a solution more in keeping with the heritage importance of the place. However, despite the elimination of pavements in the square, the market square remained a street with expansions, having lost its tangible and intangible dimension as a square over a century earlier.

2.2. Spectacles of Life and Death

The market square, as the main public space in a city where it was once the only square, was the setting for a large number of events, demonstrations and feasts. For example, in 1606, on the first centenary of the canonisation of San Vicente Ferrer, Vicente Colomer designed a mannequin of the saint and made it fly from one end of the market to the other to the amazement of the crowds at what was probably the first zipline in Valencia ([

6], p. 144). While the celebration of bull runs, student riots, tournaments and jousting battles was also common, the best spectacle in itself was the daily hustle-and-bustle of the market. In 1494, the traveller Hieronymus Münzer (1495) wrote [

34]:

“The inhabitants of the city, both men and women, walk around through the streets at night, and there are always so many people that it looks like a fair is being held (…) I would never have believed that such a spectacle could exist if I had not seen it myself, in the company of my fellow countrymen, the honourable merchants of Ravensburg. The food shops do not close until midnight, so one can buy whatever one wants at any time.”

In addition, the function of the gallows, clearly visible in the market square, was to act as a deterrent to prevent inhabitants from carrying out any crimes. Traditional punishments, even for minor crimes, were terrible: lashings; amputation of body parts such as hands, ears, or arms; exile; and even death. Offending the clergy, for instance, was punishable by nailing a hand to wood.

The executioner or

morro de vaques was a civil servant who was paid a given rate for each of these actions. Although these punishments were applied to all social classes, it was easier for wealthier individuals to evade corporal punishment or the death penalty. According to reports, in 1524 a public gallows with three stone pillars was built so that the provisional timber structure in use there since at least the 14th century, and set up for executions, would not collapse when the hanged prisoner was dropped. In 1599, it was dismantled for the wedding of Felipe III in Valencia Cathedral and was rebuilt shortly afterwards, appearing in Mancelli’s plan. In 1632, it was dismantled once again due to King Felipe IV’s passing through Valencia ([

35], p. 14–19).

The bodies of the dead were sometimes left hanging for hours, or till the next day, to serve as a public example. Although this was to set an example, market stall vendors disapproved as they felt this affected their business negatively. In the 15th century, Jaume Roig ([

36], pp. 530–533) stated: “

nor I would eat meat at the market if there were any man was hanging there”.

The dead prisoners were buried in the sector for hangings in the cemetery of Santos Juanes and later by the ravine of Carraixet ([

6], p. 67). In some of the more flagrant cases coming from the Inquisition Tribunal, not only was burial denied, but the bodies were left to be eaten by dogs. This was the case with the last victim of the Inquisition, Gaetà Ripoll, a deist schoolmaster from Ruzafa who was sentenced on 31 July 1826, following a lengthy trial in which he was accused of not going to mass on Sundays, only teaching students the commandments of the Law of God, making them use “Loado sea Dios” (“Praise be to God”) as a greeting instead of “Ave María”, and not having taken them to adore the viaticum as it passed the school. As a concession to the spirit of the times, he was not burned on the pyre but hanged in the market, over a barrel symbolically painted with flames. After the hanging, he was moved from the gallows at the market to La Pechina from where he was thrown onto the dry riverbed to be eaten by vermin ([

17], p. 429).

Prosper Mérimée (1803–1870) made seven trips around Spain between 1830 and 1864 ([

37], p. 36). On the first of these, he witnessed an execution in the market square:

“The square was far from full. The fruit and vegetable sellers had not moved from their stalls. It was easy to move around everywhere. The gallows, topped with the Aragon coat of arms, stood opposite the Lonja de la Seda, an elegant building in the Moorish style. The market square is long. The houses which form it are narrow, with several storeys, and each line of openings has a balcony with iron bars. Seen from afar they resemble huge cages. On many of the balconies with bars, there were no spectators. This indifference may be the result, perhaps, of the industrious idiosyncrasy of the Valencian people” ([

38], p. 57).

2.5. Church of Santos Juanes

This church was founded, following the reconquest of Jaime I, on the site of a mosque outside the city’s Moorish walls, yet another example of urban geographical inertia, like the market. This primitive medieval construction was rebuilt and remodelled on several occasions following the fires of 1311 and 1592, the construction of the Chapel of Communion in the mid-17th century and the transformation of the interior vault and construction of a new façade looking onto the market square in the late 17th century [

25,

30]. Furthermore, in 1700 the church of Santos Juanes applied to the Council of the City of Valencia for the cession of land behind the church, planning to build a terrace to cover the market stalls that had occupied this space since the time of Jaime I. Once the permit was granted on 1st August 1700 ([

12], pp. 11–12) the sculptor Leonardo Julio Capuz Calvet (1660–1731) was put in charge of its construction in exchange for 67 annual rents as payment for the construction of the market stalls, their doors and the upper terrace. Eighteen years later the sculptor sold this usufruct to the parish of Santos Juanes ([

40], p. 60). During the work, numerous burial sites belonging to the Moorish cemetery of the former mosque or

almacabra were unearthed. Father Tosca included this terrace with small premises on its lower perimeter in the 1704 plan. These were once known as

les paradetes de Sant Joan or

les llanterneries but are currently known as

les covetes de Sant Joan (

Figure 9). The construction of this terrace took up approximately 110 m

2 of public land from the market square.

It is striking how the increase in the level of the market square over the last 325 years has led to these market stalls becoming semisubterranean. Apparently, this was not the case initially. Recent excavation carried out in the market square for the new paving shows that the bases of the stone ashlar pilasters between the stalls were definitely designed to be seen. Based on the engravings and photographs of the steps to the right of the Lonja, and the descriptions by Llombart [

41], it is thought that the level of the square has probably increased by 70 cm since 1700—and probably more going back to 1484—although the increase in height of the paving would have been slower initially and accelerated from the mid-19th century onwards.

This façade of los Santos Juanes and its magnificent terrace, from where the spectacle of life, death, monuments and the space of the market square could be contemplated, suffered extensive damage in the bombing orchestrated by Capitán General Rafael Primo de Rivera y Sobremonte (1813–1902) in the second week of 1869 against the most densely populated areas in the city, as military repression against the federal revolution. Renowned American journalist Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904), a war correspondent for the New York Herald in Valencia, described it:

“Miraculously, the Gothic Lonja has been spared from damage. However, this has not been the case with the church of Santos Juanes, located opposite. A statue has been knocked over; the niche of the Virgin has been vandalized and defaced; the gargoyles have lost their stone wings, and the church tower has also suffered extensive damage (…) A dozen trees have been cut down in the market. Eight houses there have been rendered unusable; they will have to be rebuilt. The market itself has suffered greatly: collapsed columns, a broken roof, destroyed stalls, etc.” ([

42], p. 158) (translation by the authors).

In the space of only fifteen minutes, Stanley counted up to one hundred and thirty barricades around the market square. The position of these barricades, put up by Milicia Nacional volunteers and the army of Primo de Rivera, and their evolution in this mini-civil war, which took place between the 8 and 16 October was documented, as can be seen in two plans of Valencia from 1869 ([

14], pp. 84–85, 90–91). Stanley also mentioned the existence of graffiti on the Lonja, which at the time was crowned by a flag saying, “Federal Republic”, and the wall which closed off the Escalones de la Lonja street: “War on the general and peace to the soldier” and “Death penalty to the thief”. The description of the market square following this major battle, combined with the trademark literary style which Stanley imprinted on his chronicles, is chilling:

“What a foul stench! What disgusting stains! What a smell of blood! The blood appears in small puddles, in putrid streams, giving off deadly miasmas. As for the marks of war, it is enough to see the bullet-riddled market stalls. Observe the destroyed balconies, the chipped balustrades, the broken brackets. Look at the walls full of scars. How strange the medieval figures, with their cut-off heads and golden crowns! Even the Virgin has been sacrilegiously and irreparably mutilated, and the Santos Juanes look as if they have been shot for high treason (…) But the scars of the harsh location are far too numerous to list. They are everywhere; they become visible in the ruin and damages of the square, in the fallen trees which once provided shade in the market square, in the horrendous ruins of the surroundings” ([

42], pp. 157–158) (translation by the authors).

Twelve days later, on 28 October, Stanley was already in Paris when he received the task of locating and interviewing the missionary David Livingstone (1813–1873). Towards the end of 1871, Stanley found him in Ujiji (Tanzania), where he remained with him until March 1872. A year later, Stanley, a global celebrity at this point, returned to Valencia as a war correspondent to report on the disturbances brought about by the cantonal revolution of Valencia in August 1873, although in his opinion these revolutionaries paled in comparison to those of the federal revolution of 1869.

From its magnificent 300-year-old vantage point, the church of Santos Juanes witnessed and, as seen, was even a victim of, historical developments. Unfortunately, the fact that this vantage point and possible access to the church are now unusable—partly due to the transformation from an urban historic square to a street with expansions—is sadly a wasted opportunity, preventing it from becoming part of the setting of the market square, as well as of the comings and goings of residents and tourists.

2.6. Panses Square, Today Called Compañía Square

This building, located behind the Lonja, was also witness to major episodes in the city’s history. Built between 1595 and 1631 on a site specifically selected by San Francisco de Borja (1510–1572) for his foundation, it appeared to still be under construction on Antonio Mancelli’s (¿?–1645) plan from 1608. The Jesuitical professed house or adjoining building in Cenia Street was built between 1668 and 1669 and, as a result, Father Tosca’s (1651–1723) plan faithfully reflects the full layout. In 1767, following the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain on the orders of Carlos III (1716–1788), it seems the church was left half-abandoned and the Casa Profesa was used as the Archive for the Kingdom between 1810 and 1963 [

13].

The name of this square, known traditionally as Panses Square, as it was where most of the raisins were sold, eventually changed to Compañía Square. It was customary to read the daily press there. A plaque on the back façade of the Lonja commemorates the 23 May 1808, when the people of Valencia declared war on Napoleon, supporting the command of the palleter Vicente Doménech, spurred by indignation at the news published in La Gaceta on the abdication of King Fernando VII and the advances of French troops in Spain. The profession of palleter consisted in selling sulphur wicks, lighting them to disinfect the empty wine barrels and prevent the proliferation of microorganisms which might alter the wine.

Sixty years later, when the Revolution of September 1868—known as “la Gloriosa”—led to Queen Isabel II (1830–1904) being deposed and exiled, the Junta Superior Revolucionaria de Valencia, headed by the former mayor José Peris y Valero (1821–1877), ordered the demolition of the Jesuitical church [

43]. Years later, in 1885, the architect Joaquín María Belda Ibáñez (1839–1912) built a new church, still seen today, following the outlines of the demolished church. The residential buildings on the corners of Lonja Street and Cenia Street and Cordellats Street and Danzas Street, examples to be used for in-depth analysis, have witnessed—as is the case with other buildings—part or all of what has happened in the history of the square or the Lonja itself.

The building at Compañía Square n. 3 on the corner of Cordellats Street is of great interest (

Figure 10). This three-storey building is made up of a ground, first and second floor. At first glance, the dressings of the windows on the first and second floors and the railings of the balconies appear to date from the early 20th century. However, this is merely the appearance. In fact, the railing of the first-floor balcony, with its Modernist decoration and lower frieze with bees representing hard work, is made of cast mould, and the solid base of the balcony probably dates from the same period, despite the possibility of a more recent intervention. The balcony windows on the first floor, looking onto Danzas Street, still conserve the valances of die-cut wood board used to protect the external solar protection blinds of the building, another characteristic feature of the Valencia of the time. The wooden joinery, with an upper clerestory and interior shutters, may also date from the same period. In fact, the iridescence of some of the glazing of the clerestories reveals that they were early 20th century blown glass.

However, the upper balcony with rounded corners is much older (

Figure 10b), as can be seen from the ceramic tile on the underside of the balcony on Danzas Street, made up of pieces measuring half a palm (11.25 cm), a measure for ceramic production which disappeared around 1740 [

44]. A more detailed examination reveals that the railings are wrought iron from a square section and that the lower protective band with flowers framed in rhomboids and a central ring with scrolls, also wrought iron, were subsequently added with small rivets, probably at the time when the lower Modernist balconies were added. It could be assumed that the dressings of the second-floor windows are not Modernist, but date from the 18th century Baroque, although at that point the artisan dwellings were not decorated, far less so on the top floor.

But there are other striking details (

Figure 10c): the ground floor in rough ashlar, with a simple corner without decoration and a Roman arch at the entrance. This suggests it was a medieval construction built before the War of the Guilds (1519), after which Roman arches were rarely found at the entrance of residential buildings. The brick construction visible in sections missing rendering is in brick-supplemented rammed earth in dimensions characteristic of the 14th century. In contrast, the industrial brick used to block off the Roman arch is characteristic of the late 19th or early 20th centuries, which is in line with the dates of the interventions on the first-floor balconies. The somewhat irregular distribution of the openings on the ground floor, the windows on the first floor, and the loggia on the second floor with no proposed vertical symmetry, also suggests a building prior to the advent of the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos, which sought geometric order on façades whenever possible. In addition, as will be detailed later on, the 18th century saw the start of a process of completing medieval crown loggias, which were transformed as yet another floor on the building in order to accommodate the city’s growing population, a process not observed on this building.

This building is known to have been the residence of doctor and writer Jaume Roig (1407 or 1409–1478). Could this be the same building where the famous author of L’Espill lived? It is, in fact, highly probable that at least the walls of the building are mostly those of the dwelling of Jaume Roig. The writer’s façade would have been made up of half-body or even full-length windows with wooden railings flush with the wall, with no projections. Undoubtedly, the joinery was made up of blind shutters with no glazing, and in winter wooden frames with oiled linen were used to let in the light while still offering protection from the wind and partly the cold. From the exterior, no evidence is seen of the ceilings of the building, where wooden beams and joists from this period and some details may have survived the passing of time.

The building on Lonja Street no. 8, on the corner of Compañía Square and Cenia Street (

Figure 11a), is shown in the 1810 engraving depicting the uprising of the Valencian people against Napoleon and already appears with the same five storeys found today. In fact, the stone doorway with rounded edges; the joinery of the main door; the format of the balcony, projecting three palms (67.5 cm) with iron braces that clear to avoid the openings (

Figure 11b); the smaller balconies with rounded corners (

Figure 11d); the simple bars of the railings, produced by a blacksmith’s hammer and not a cast mould (

Figure 11c); the full-body closed-off balconies with a square section and curved corners to avoid the use of the spiked joint, reserved only for the upper edge; and the ceramic tile of the underside of the balconies suggests it dates to 1770–1780 (

Figure 11b). The wooden eaves that look both onto Lonja Street and Cenia Street are indicative of a construction which is also characteristic of the 18th century or earlier, as in the 19th century pressure from the Academia de Bellas Artes and local regulations led to the elimination of this type of wooden eave and to the construction of finishing cornices. Under the yellow paint, recently applied, the extensive, slightly irregular and bulging gypsum rendering characteristic of the 18th century is still found, clearly visible.

The balconies on the façade of Cenia Street, project three palms (67.5 cm), feature bars, a lower filigree band and a solid ledge measuring a palm and a half (33.75 cm) on the underside of the balcony, suggesting that this façade was remodelled circa 1840. The joinery throughout the building is wooden, with shutters at least on the main floor. When the balconies were added the late 18th century joinery would almost certainly have been large blind wooden shutters where, instead of glass, frames with oiled linen would let in the light in and offer protection from the cold. The use of glass in residential buildings in Valencia took off only after 1840.

However, the stone ashlar corners have a smooth edge and no decoration; a change in wall thickness is detected between the first three floors and the last two; there is a larger separation of the mezzanine between the third and fourth floors; and the ashlar bond on the plinth, which was rougher, is also different from that used in the doorway, which was larger, thinner and only partly connected to the rest of the plinth. This suggests that there may have been an original building with ground, first and second floors which, later, in 1770–1780, was remodelled, adding the large ashlar doorway and two upper floors. All the openings were remodelled, introducing new balconies and closed balconies, a type of intervention that was extremely popular in the city at the time. All these details point to the original existence of a medieval building, probably accessed via a Roman arch where the current doorway now stands; the walls, and perhaps the interior ceiling, were swallowed up by the 18th century intervention, giving the building the appearance it still conserves today.

In conclusion, both buildings appear to have witnessed not only the life of one of the greatest literary figures of the Valencian language and the declaration of war from the Valencian people against Napoleon, but also the construction of the Lonja: Jaume Roig’s home, with fewer changes in volume, and the building on Lonja Street considerably heightened by two new floors. Both buildings are therefore several centuries old and are as important as the Lonja both in terms of the context provided and as examples of the evolution of the built material culture of housing within the city. Numerous medieval buildings like these are still conserved around the Lonja, masked to varying degrees by the transformations they have suffered through time.

2.8. The Dwellings

The area around the Lonja, as well as including these major buildings and the public space in the square, is strongly characterised by tall residential buildings with narrow plots, conferring a unique appearance to this part of the city. As mentioned earlier, the surroundings of a building as notable as that of the Lonja are completely inextricable from the monument itself, to the point that its value depends on what is found around it. The buildings of the market with its workshops or displays on the ground floor have been and continue to be one of the most important elements of the setting.

As seen earlier, little attention is paid to detail in these buildings in the first plan of Valencia, drawn by Mancelli in 1608. Mancelli draws all these buildings practically identical, with a gable roof, an entrance door on the ground floor and two windows on the first floor. Although the drawings of the buildings are extremely simple, Mancelli also provides further information: these are narrow plots, with equally narrow façades looking onto the street. The buildings are grouped into blocks where some plots are deeper. As indicated previously, the market area was close to the Moorish wall so the surroundings of the Lonja, as it stands at present, are the result of two different processes. On the one hand, in the area within the city walls, the existing fabric of houses with courtyards and narrow streets is transformed, gradually replacing or transforming the buildings (

Figure 15a), while on the other, in the area outside the walls, the territory is colonised by medieval

pueblas or settlements with parallel homogeneous plots which run perpendicular to irrigation ditches or paths [

27] (

Figure 15b). In both cases, these “Christian houses” consisted of two floors (ground and first floor), with a space on the ground floor located by the entrance from the street and designed for use as a shop or artisan workshop, a space at the back towards the interior courtyard, used for the kitchen and alcoves, and a room or chamber at the top for use as a bedroom ([

17], pp. 86–87) (

Figure 15c).

In addition, throughout the 14th century, the Consell worked expressly on straightening and widening streets, creating squares and new streets, closing the cul-de-sacs to prevent waste from accumulating in them [

22] or opening them up to create new connections [

22]. An interesting example is the order of 1383 to rectify the outline of the streets beyond the Gate de la Boatella ([

22], p. 1526). The streets were also organised by eliminating any shutters, benches, protrusions, etc., which invaded them, hindering circulation [

22]. As mentioned earlier, in 1447 a fire destroyed some of the houses in this part of the city so the planned reconstruction included blocks with parallel plots open to perpendicular streets.

Therefore, Mancelli’s depiction of this part of the city in 1608 is undoubtedly the result of all these operations and although the plan appears limited in detail, the complex blocks stemming from the Moorish structure, the parallel plots resulting from the pueblas, and the blocks affected by the fire and reconstructed with blocks between parallel streets can be seen clearly.

On the plan drawn by Father Tosca in 1704, almost a century after Mancelli’s plan, the buildings in the surroundings of the Lonja appear greatly transformed. It shows the porticoes on several sides of the market square in buildings with a ground floor and an additional four storeys, constructions that were quite tall for their time. These porticoes (

Figure 16c,d) are the ones recorded by the numerous travellers who immortalised the market square in the first half of the 19th century (including: Laborde 1811; Trichon 1834–1835; Chapui 1844) [

20]. Evidence of these porticoes is found in the files from the late 18th century in the Municipal Historical Archive of Valencia (

Figure 16a,b). In some of these porticoed buildings, applications were made for permits to add balconies while in others the addition of a single storey, changing from a ground floor plus two to a ground floor plus three, was requested [

27]. Archive files connected with the market square in the late 18th century include a large number of applications to build balconies or replace old balconies with newer ones (in keeping with the transformations observed throughout the city); demolishing protrusions; reconstructing the exits to the roof and adding railings; demolishing and building new houses with balconies; some inspections for houses at risk of ruin. In 1783, there was an inspection of the portico of a house in the convent of La Merced (AHMV 1783). Different files from 1796, and especially 1797, refer to the repair of damage following the fire which had taken place in the market: “repairing the exit to the roof, repairing windows and other works required following the market fire”, “rebuilding a house, remodelling the windows and balconies of the attic, following a fire”, “rebuilding a charred apartment and incorporating a balcony”, “leaving the house as it was originally”, etc.

In the surrounding streets, Tosca also depicts buildings that are unusually tall for that period, with no porticoes, but with wide openings for workshops or shop windows. All through the 18th century, AHMV files frequently requested permission to work on the doors of the ground floor. There are many files related to the opening of doors, “making a door jamb” or “making two door jambs”, in some cases with “ashlar stone”, so it is understood that this is about reconstructing one or two door jambs on the ground floor, perhaps to widen them.

There is currently no trace of the porticoes of the market square that disappeared in the second half of the 19th century, as described by Teodoro Llorente in 1889: “the porticoes of the houses disappeared, their narrow windows were widened, the small wooden balconies were replaced with other iron ones, conferring a modern appearance to the entire building”. Also, around this time, Blasco Ibáñez described the buildings around the market square: “groups of narrow façades, clustered balconies, walls with lettering, and on all the ground floors, shops selling foodstuffs, clothing, drugs and drink, with doors displaying the names of the establishments, as many saints as are found in heaven and as many common animals of all types are found” [

45].

Furthermore, the plans and views from the 19th century show a row of buildings opposite the Lonja and beside the church of Santos Juanes, even seen in photographs from the early 20th century. These buildings were demolished to make space for the construction of the central market. On the corner of this block (identified as number 396 on the plan from 1831) close to the church of Santos Juanes, was the building of the Principal, described by Blasco Ibáñez as “a very poor building, a miserable guardhouse, whose door is guarded by the watchman, weapon in hand, with a bored demeanour, and a bayonet grazing the off-duty soldiers, who are eating their tasteless meal while contemplating the sea of foods which spreads over the square” [

45].

In these photographs from the early 20th century, the top end of the same block, looking onto Conejos Street and the porticoed market was made up of a series of narrow houses of different types commonly found in the area of the Lonja (

Figure 17): the workshop dwellings, with a workshop and/or shop on the ground floor leading to one- or two-storey dwellings and the chamber or attic store which form part of the medieval legacy of the city (

Figure 17a); the stairway houses are small residential buildings, mostly built during the 19th century, combining a workshop or shop on the ground floor with a small entrance to a narrow stair for accessing the independent dwellings on the upper floors, usually one per floor, with minimal dimensions (

Figure 17b); the workshop dwelling with a double shop window on the ground floor, possibly the result of merging two workshop dwelling plots (

Figure 17c). These can be considered a derivation of the single workshop dwelling given that it functioned in the same way, with access to the upper floors through the shop on the ground floor. In some of the areas surrounding the Lonja it is also possible to find communal residential buildings with two, three or four dwellings per floor with access to the common staircase through a door on the ground floor, usually connected to ground floor commercial premises with shop windows (

Figure 17d).

There are currently relatively few examples of medieval workshop dwellings, but some can still be found at different points within the market square and Collado Square and Ercilla Street, Palafox Street, etc. Some of these houses were uninhabited on the upper floors as the living space was accessed through the store. In one of these, a ceiling was identified, with wooden beams, laths and ceramic tile, and given the similarities of its decoration to one of the ceilings of the palace of the Valeriola family, it could date to the 15th century [

27]. In some cases, interventions were carried out to establish direct access to the ground floor staircase from the street, separating the living and commercial spaces. Workshop dwellings with two shop windows on the ground floor were extremely common throughout the southeast side of the market square, which featured a series of buildings of this type. Many of these still survive, and both the ground floor shops and the upstairs dwellings have been remodelled.

The surviving buildings, which have undergone numerous interventions and transformations, have become a hybrid mix of architectural styles and elements. Many of these transformations are documented in the files of the AHMV [

27] and their history can be briefly examined for a more in-depth understanding of the value of these survivors of history. In the 18th century, closed-off iron balconies were inserted, the loggias or small chamber windows were blocked off, full-length windows were opened onto the balcony, and one or two floors were also added. The widespread presence of balconies in modern Valencia is explained by an 18th century transformation changing a city with plain façades with windows into a city with balconies on all buildings and heights. Closed-off balconies with wrought iron plates and bars, ceramic flooring and struts to support the structure are from this period. In the mid-18th century, the size of ceramic floor tiles changed (from 11.25 cm per side to 22.5 cm per side, or from half to one Valencian palm), lightening the load of the “cages” as fewer plates were needed to secure the tiles. The installation of balconies was associated with opening up windows to create doors for accessing the balconies, in most cases adding joinery, and shutters with no glass, usually folding into the interior side of a thick façade wall seen on the edge of the windows. Interventions like these are widely seen in the buildings around the Lonja, although the examples currently found on the stretch from the market square between the Lonja and Tabla de Cambios Street and between Encolom Street and Bolsería Street are particularly interesting. On these stretches, we find two groups with three and four dwellings which perfectly illustrate these interventions, as well as others from the 19th century (

Figure 18).

In the first half of the 19th century, there continued to be intensive updating of the façades of pre-existing buildings [

27]: closed-off balconies were still used, although they were progressively supported by brick brackets which eliminated the need for struts; iron balustrades were added on roofs; in some cases, the access to the living quarters of the workshop dwellings was separate from the ground floor shop thanks to a door added on the façade. The access to the dwelling or dwellings in the upper part of these buildings has always been a weak spot, causing abandonment and deterioration. It is still possible to find abandoned buildings of these characteristics, although possible compatible solutions have been put in place, very similar to those already proposed in the 19th century. In this regard, in Collado Square (

Figure 19), the houses on the north side have mostly undergone interventions to divide the commercial openings from the ground floor to create an independent entrance leading to the upper floor dwellings.

In the second half of the 19th century, but especially in the final twenty-five years, windows with glass were either added outside the shutters or replaced altogether, while wrought iron bars were incorporated into balconies, increasing the potential for decoration and variety. On Palafox Street (

Figure 20), it is possible to observe a row of late 19th century workshop dwellings (except for the one on the corner with Blanes Street which is from the late 18th century). These are probably the result of remodelling interventions in previous buildings. In these it is possible to observe how decoration is added to the façade with rustication (used in Valencia from the 1830s), strips separating floors all along the façade, brackets and pilasters adding reliefs to the rendering, which becomes more prominent thanks to colour contrasts; wrought-iron balconies resting on brackets and dating to 1870–1880; and wooden joinery with glazing and

frailero shutters (which have not been replaced in restoration interventions).

Some stairway houses remain on d’En Gall Street, around the corner from Palafox Street (

Figure 20). The architectural elements of these two dwellings go back to the second half of the 18th century or early 19th century. Both buildings still conserve the staircase on the façade, visible thanks to the entrance door beside the ground floor shop window and the small windows of the stairwell. Files have been found [

27] from the late 19th and early 20th century proposing to move the stairway on the façade closer to the second set of stairs, thus freeing the façade bay and providing a span for a larger room. This type of intervention is usually linked to the widening of the small staircase windows, converting them into windows or full-length balcony doors. Interventions like this can be seen on Pere Compte Street.

Immediately surrounding the Lonja, there are also examples of notable communal residential buildings, probably the result of the merging of medieval plots with narrow workshop dwellings and a remodelling process taking place from the mid-19th century onwards. These buildings include neoclassical mouldings and pediments, wrought iron balconies, and—although covered by paint—the ashlar effect decorating the entire façade as can be seen in photographs from the late 20th century. Buildings of this type, with a communal entrance from the street used to access dwellings, generally two per floor, can be found in several locations around the Lonja, from the market square to Collado Square, and also including Derechos Street or d’En Gall Street, etc.

From the second half of the 19th century, the city of Valencia was immersed in a frenzied rhythm of remodelling and renovation of both the public space and the housing stock. Squares and streets were opened up, new alignments were created in order to widen the small narrow streets of the medieval layout, and older insalubrious residential buildings disappeared to make way for collective housing blocks with improved ventilation and functionality. This process also reached the surroundings of the Lonja. If the “Proyecto de Reforma Interior” by L. Ferreres (1891) had been executed, at present the surroundings of the Lonja would be drastically different and there would be no call for a study of these characteristic dwellings in the market areas. The idea of opening up wide avenues and streets to replace the buildings around the Lonja and the market was a constant during almost half of the 20th century, as recorded in numerous plans and projects. Among these, it is worth noting the plan of “Nuevas líneas para la Reforma Interior de Valencia” by J Goerlich in 1929, which foresaw a complete transformation of the entire area, connecting to Ayuntamiento Square, and opening up the Oeste Avenue behind the central market. The renewal plan, as well as opening Oeste Avenue as far as the church of Santos Juanes, especially affected the southern access to the square from San Fernando Street as María Cristina Avenue and Ayuntamiento Square were now connected. The creation of the new avenue led to the demolition of different blocks of housing up to San Vicente Street and the construction of the collective housing buildings is still seen in the same spot today. These dwellings, mostly built in the 1930s, were on a far greater scale than the construction in the square (although in keeping with porticoed buildings which previously must have been in this area), as well as curved chamfers in stark contrast with the smooth linear façades of this part of the city (

Figure 21).