Islamic Influence on the Local Majapahit Hindu Dwelling of Indonesia in the 15th Century

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Objectives

- This study aims to comprehend the impact of Islamic teachings on the architectural transformation of the building typology of houses during the Majapahit Era as a Hindu kingdom.

- This study aims to understand the Islamic teachings that influenced the transformation of spatial distribution within the houses.

- This study aims to understand the transformation of architectural elements in the Majapahit Kingdom during the Influence of Islamic teachings.

1.2. Research Limitations

1.3. History of Islam in the Majapahit Kingdom

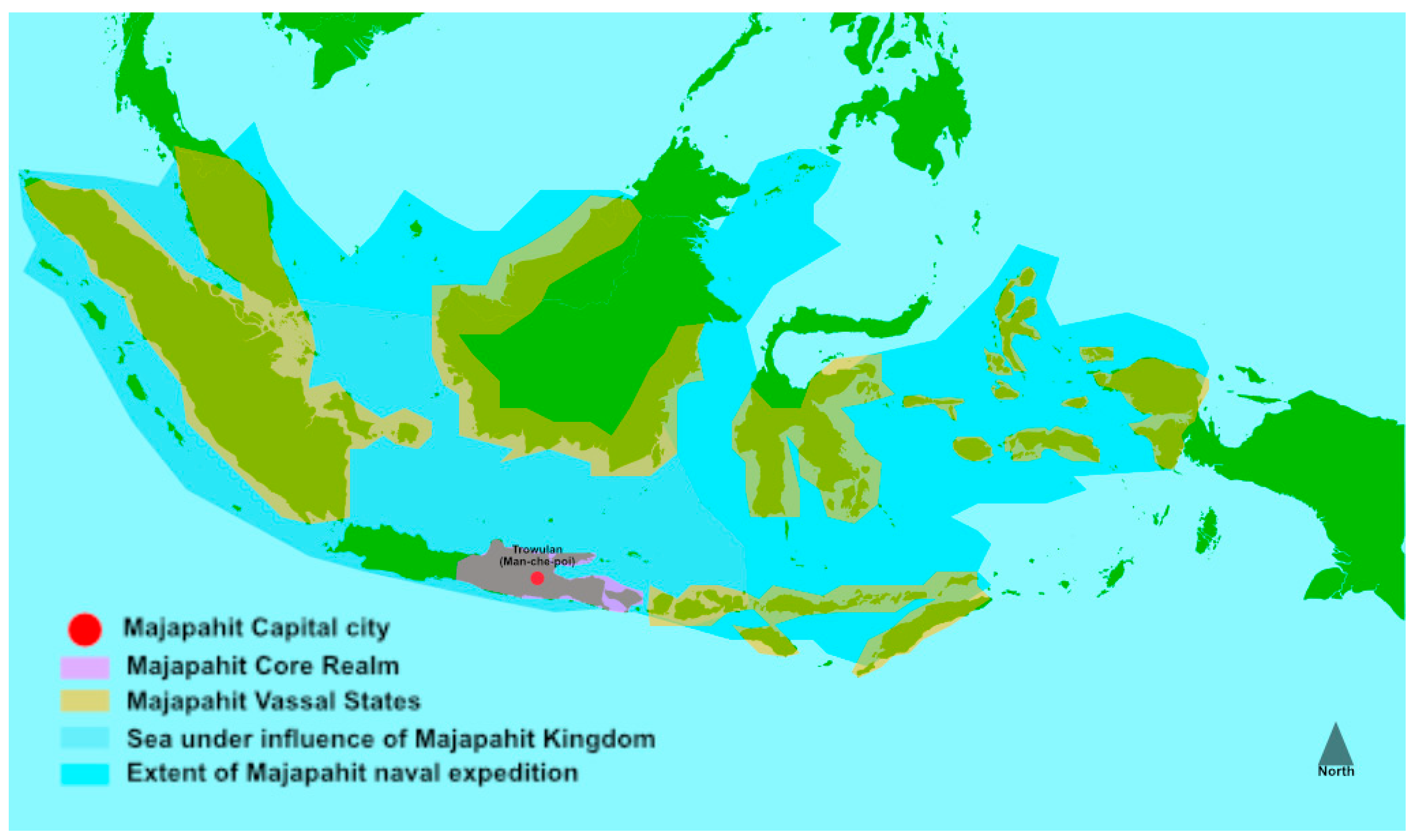

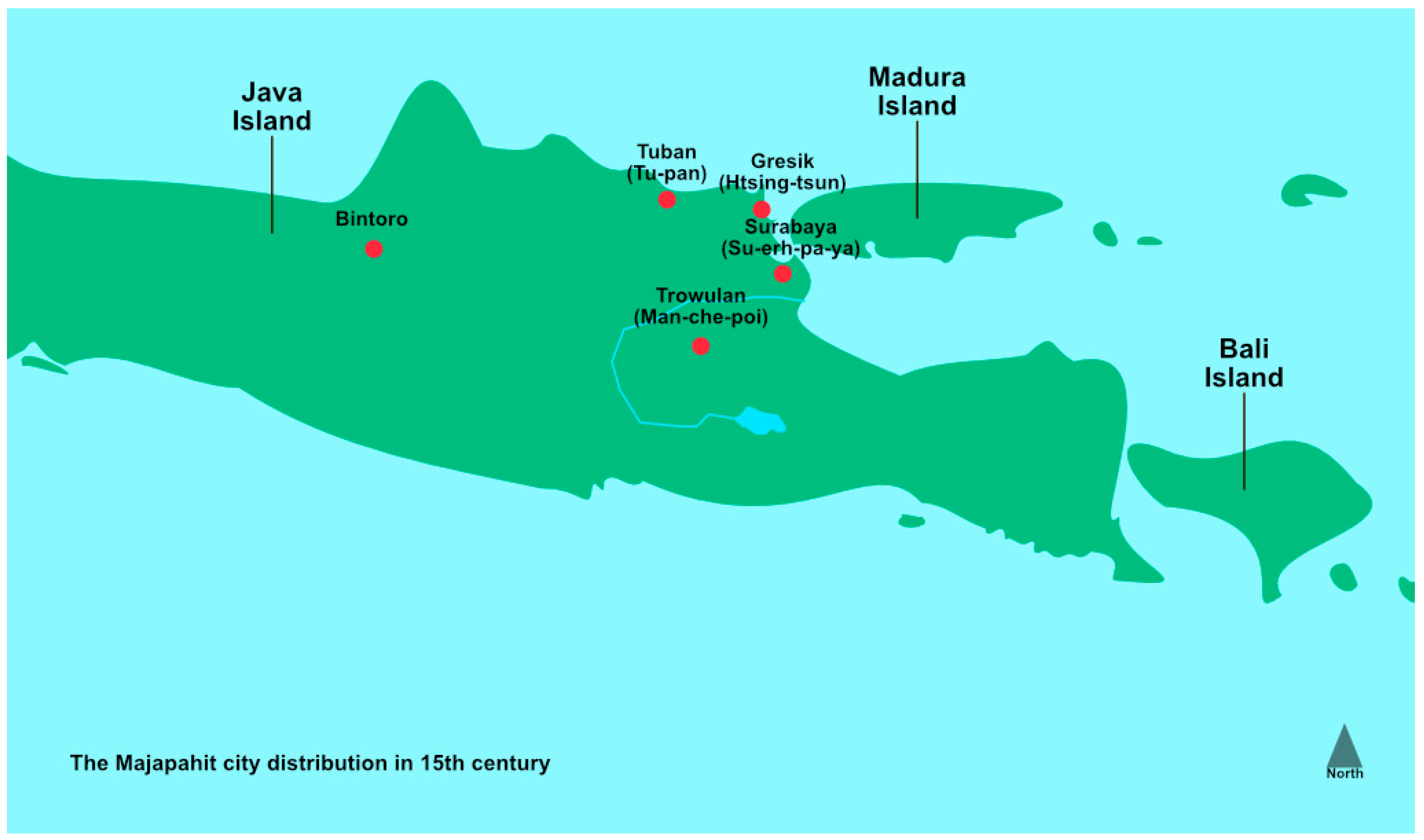

1.3.1. Geographical Information of the Kingdom

1.3.2. The Majapahit Kingdom

1.3.3. Housing in the Majapahit Kingdom, Trowulan

1.3.4. The Islamic Community in the Majapahit Kingdom

1.3.5. Islamic Housing in Majapahit Kingdom, Bintoro

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Architectural Documentation Methods

2.2. Majapahit-Style Architectural Documentation

2.3. Building Typology, Majapahit Kingdom

2.4. Spatial Distribution, Majapahit Kingdom

2.5. Architectural Elements, Majapahit Kingdom

3. Results

3.1. The Influence of Islam Related to the Building Typology

3.2. Building Composition of Muslim People

3.3. The Influence of Islam on Spatial Distribution

O believers! Do not enter the homes of the Prophet without permission, ˹and if invited˺ for a meal, do not ˹come too early and˺ linger until the meal is ready. However, if you are invited, then enter ˹on time˺. Once you have eaten, then go on your way, and do not stay for casual talk. Such behaviour annoys the Prophet, yet he is too shy to ask you to leave. However, Allah is never shy from the truth.

Moreover, when you ˹believers˺ ask his wives for something, ask them from behind a barrier. This is purer for your hearts and theirs. Furthermore, it is not suitable for you to annoy the Messenger of Allah or marry his wives after him. This would undoubtedly be a significant offence in the sight of Allah.

3.4. The Influence of Islam on the Architectural Elements

Narrated Abu Hurairah, God is pleased with him. I heard the Prophet Peace be upon him, saying, “Allah said, ‘Who are most unjust than those who try to create something like My creation? I challenge them to create even the smallest thing; a wheat or a barley grain’.”

3.5. Matrix of Categorization

4. Conclusions

4.1. Influence of Islam on Majapahit Dwellings

4.2. Islamic Influences on Buildings’ Typology

4.3. Islamic Influences on Spatial Distribution

4.4. Islamic Influences on Architectural Elements

4.5. Suggestions for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Auliahadi, A.; Nofra, D. Tumbuh dan Berkembangnya Kerajaan-Kerajaan Islam di Sumatera dan Jawa. Maj. Ilm. Tabuah: Ta`Limat Budaya Agama Dan Hum. 2019, 23, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubontubuh, C.P.; Martokusumo, W. Meeting the Past in the Present: Authenticity and Cultural Values in Heritage Conservation at the Fourteenth-Century Majapahit Heritage Site in Trowulan, Indonesia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam Transformasi Islam Kultural ke Struktural (Studi Atas Kerajaan Demak). Tsaqofah Tarikh 2016, 1, 63–76. [CrossRef]

- Zuhroh, F. Muslim Champa dan Islamisasi Jawa Pada Masa Akhir Kerajaan Majapahit. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Ampel, Surabaya, Indonesia, 3 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kasri, M.K.; Semedi, P. Sejarah Demak Matahari Terbit di Glagahwangi; badan arsip dan perpustakaan provinsi jateng; Kantor Pariwisata dan Kebudayaan Kabupaten Demak: Jawa Tengah, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Susanti, B.T.; Sunarimahingsih, Y.T. Bentukan Arsitektur Rumah Tinggal “Tradisional” Pantura Dikaji Dari Aspek Tektonika dan Stilistika; Studi Kasus Rumah Tradisional di Demak; Unika Soegijapranata: Semarang, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mortada, H. Traditional Islamic Principle of Built Environment; RoutledgeCurzon: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 0-203-42268-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ngationo, A. Peranan Raden Patah Dalam Mengembangkan Kerajaan Demak Pada Tahun 1478–1518. Kalpataru J. Sej. Dan Pembelajaran Sej. 2018, 4, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilo, A.; Wulansari, R. Peran Raden Fatah Dalam Islamisasi di Kesultanan Demak Tahun 1478–1518. TAMADDUN J. Kebud. Dan Sastra Islam 2019, 19, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, J. Balinese Architecture; Tuttle Publishing: Singapore, 2003; ISBN 978-1-4629-1442-7. [Google Scholar]

- Herwindo, R.P. Transformasi Arsitektur Permukiman Tradisional di Jawa Dari Masa Hindu-Budha ke Masa Islam; Universitas Katolik Parahyangan: Bandung, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Herwindo, R.P. Kajian Estetika Desain Arsitektur Majapahit; Universitas Katholik Parahiyangan: Bandung, Indonesia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, R.A.; Kasdi, A. Arsitektur Rumah di Kawasan Cagar Budaya Trowulan (Studi Pemukiman Majapahit Abad ke-14 m). AVATARA E-J. Pendidik. Sej. 2017, 5. Available online: https://ejournal.unesa.ac.id/index.php/avatara/article/view/21084 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Anita, D.E. Walisongo: Mengislamkan Tanah Jawa. Wahana Akad. 2014, 1, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartapranata, G. Majapahit. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Majapahit&oldid=1076186235 (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Thamrin, M.Y.; Putri, G.S. Lima Fakta Tentang Majapahit, Kerajaan Terbesar di Nusantara—Semua Halaman—National Geographic. Available online: https://nationalgeographic.grid.id/read/131666050/lima-fakta-tentang-majapahit-kerajaan-terbesar-di-nusantara (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Susilo, A.; Sofiarini, A. Gajah Mada Sang Maha Patih Pemersatu Nusantara di Bawah Majapahit Tahun 1336 M–1359 M. KAGANGA J. Pendidik. Sej. Dan Ris. Sos.-Hum. 2018, 1, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiah, N. Kerajaan Nusantara; Ensiklopedia Ilmu Pengetahuan Sosial; Mediantara Semesta: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2009; ISBN 978-602-8489-35-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyudi, D.Y. Kerajaan Majapahit: Dinamika Dalam Sejarah Nusantara. Sej. Dan Budaya 2013, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, A. Kerajaan Majapahit. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/53b5ebab7244412aa821581bd68bff7c (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Birsyada, M.I. Legitimasi Kekuasaan Atas Sejarah Keruntuhan Kerajaan Majapahit Dalam Wacana Foucault. Walisongo J. Penelit. Sos. Keagamaan 2016, 24, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanus Johannes de, G.; Theodore, G.T.P. Kerajaan-Kerajaan Islam Pertama di Jawa: Peralihan Dari Majapahit ke Mataram, 2nd ed.; Grafiti Press: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Colless, B.E. External Evidence on the Geography and Ethnology of East Java in the Majapahit Period; Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Winarto, Y.; Santosa, H.R.; Ekasiwi, S.N.N. The Climate Conscious Concept of Majapahit Settlement in Trowulan, East Java. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 179, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, M. Mengungkap Jejak Kadipaten Terung di Akhir Majapahit. Available online: https://m.merdeka.com/peristiwa/mengungkap-jejak-kadipaten-terung-di-akhir-majapahit.html (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Wibawanto, W.; Nugrahani, R.; Mustikawan, A. Reconstructing Majapahit Kingdom in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the Multidisciplinary Design: Harmonizing Design in Today’s Society, Technology and Business; Telkom University: Bandung, Indonesia, 2016; Volume 2, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Rikyana, I.G. Keunikan Bangunan Bale Sakenem (Wong Kilas) di Batuan. Anala 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiyansah, A.; Ardiyan, A.; Mahardhika, S. Lingkungan dan Pemukiman Zaman Kerajaan Majapahit dalam CGI (Computer Generated Imagery). Humaniora 2010, 1, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojak Official Guide of Museum of Majapahit Trowulan; Museum Majapahit Trowulan: Mojokerto, Indonesia, 2022.

- Janah, I.R.; Ayundasari, L. Islam dalam hegemoni Majapahit: Interaksi Majapahit dengan Islam abad ke-13 sampai 15 Masehi. J. Integrasi Dan Harmoni Inov. Ilmu-Ilmu Sos. JIHI3S 2021, 1, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghfiroh, F. Toleransi Umat Beragama: Studi Posisi Umat Islam di Kerajaan Majapahit; Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Ampel: Surabaya, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Isno Pendidikan Islam di Majapahit Dan Dakwah Syeikh Jumadil Kubro. J. Pendidik. Agama Islam 2015, 3, 59–80. [CrossRef]

- Fadhilah, N. Jejak Peradaban dan Hukum Islam Masa Kerajaan Demak. Al-Mawarid J. Syariah Huk. 2020, 2, 33–46. Available online: https://journal.uii.ac.id/JSYH/article/view/17257 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Tunggal Dewi, T.; Wakidi; Arif, S. Peranan Sultan Fatah Dalam Pengembangan Agama Islam Di Jawa. PESAGI J. Pendidik. Dan Penelit. Sej. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afidah, N. Perkembangan Islam pada Masa Kerajaan Demak. J. Studi Islam Dan Kemuhammadiyahan JASIKA 2021, 1, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardjono, A.B.; Bharoto; Sudarwanto, B.; Prianto, E. Puspa Ragam Bentuk-Bentuk Arsitektur Setempat; Penerbit Tigamedia: Semarang, Indonesia, 2022; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Almaimani, A.; Nawari, N.O. BIM-Driven Design Approach for Islamic Historical Buildings. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 4947–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaimani, A.M.; Nawari, N.O. BIM-Driven Islamic Construction: Part 1—Digital Classification. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering 2015, Austin, TX, USA, 21 June 2015; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2015; pp. 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary Definition of TAXONOMY. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/taxonomy (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Collins Dictionary Taxonomy Definition and Meaning|Collins English Dictionary. Available online: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/taxonomy (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Suprianto, B.; Sidhartani, S. Karakter Tokoh Hayam Wuruk. Vis. Herit. J. Kreasi Seni Dan Budaya 2019, 1, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bin Syamsuddin, Z.A. FAKTA BARU WALISONGO: Tela’ah Kritis Ajaran, Dakwah, Dan Sejarah Walisongo, 4th ed.; Penerbit Imam Bonjol: Jawa barat, Indonesia, 2017; ISBN 978-623-97859-0-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rachman, D.A. Majapahit Terracotta Figurines: Social Environment and Life. Humaniora 2016, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susannawaty, A. Kajian Bentuk dan Makna Simbolik Figurin Gerabah Majapahit (Periode Hayam Wuruk 1350-1389 M). ITB J. Vis. Art Des. 2008, 2, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaenal, A. SUNAN GIRI: Konstruk Elite Islam Terhadap Perubahan Sosial pada Masa Akhir Kekuasaan Majapahit Akhir Abad XV—Awal Abad XVI; Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Ampel: Surabaya, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- dictionary.cambridge.org Interpretation. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/interpretation (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- National museum of Jakarta. Hidup di Ibukota Majapahit; National Museum of Jakarta: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Roesmanto, T. A Study of Traditional House of Northern Central Java—A Case Study of Demak and Jepara. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2002, 1, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, M. Typology as a Form of Convention. AA Files 1984, 6, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, R. How to Create a Building Typology?: Typological Matrix for Mapping 19th Century Synagogues. Zb. Rad. Građev. Fak. 2014, 30, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudwiarti, L.A. Generasi Lanjut Usia Mandiri Dan Fenomena Pergeseran Aspek Eko-Morfologi Kawasan Hunian. J. Arsit. Komposisi 2019, 13, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Basri, M. Elemen-elemen Arsitektur Vernakular dalam Analisa Ruang dan Bentuk pada Gereja Pohsarang. Rev. Urban. Archit. Stud. 2017, 15, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solodilova, L.A. The Necessity of Using Developed Cultural Traditions in Contemporary Architecture of South of Russia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hosiah, A.; Putrie, Y.E. Keindahan Dan Ornamentasi Dalam Perspektif Arsitektur Islam. J. Islam. Archit. 2012, 2, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiryomartono, B. Javanese Culture and the Meanings of Locality Studies on the Arts, Urbanism, Polity, and Society; Lexington Books: Blue Ridge Summit, PA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4985-3308-9. [Google Scholar]

- Arrosyid, H. Filosofi Dakwah “Banyu Mili” Sang Wali di Bumi Wilwatikta. J. Inov. Penelit. 2022, 3, 4393–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaqim, M. Sunan Ampel Dalam Aktivitas Kehidupan Sehari-Hari, Menyebarkan Agama Islam Dan Kegiatan Sosial Tahun 1443-148. Al-Maquro’ J. Komun. Dan Penyiaran Islam 2022, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofyan, Y.M. Kekuasaan Jawa: Studi Komparatif Sistem Kekuasaan Kerajaan Majapahit; Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Idham, N.C. Javanese Islamic Architecture: Adoption and Adaptation of Javanese and Hindu-Buddhist Cultures in Indonesia. J. Archit. Urban. 2021, 45, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quran Chapter 33:53 Surah Al-Ahzab—53. Available online: https://quran.com/al-ahzab/53 (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Muthiah, W.; Sachari, A. Motif Kalamakara Pada Temuan Perhiasan Emas Era Majapahit Koleksi Museum Nasional Jakarta. Pros. SENI Teknol. DAN Masy. 2021, 3, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bukhori, M. Sahih Al-Bukhari Vol. 9; Darussalam: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1997; ISBN 9960-717-31-3. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sulaksono, A.; Adas, Y.A.; Almaimani, A. Islamic Influence on the Local Majapahit Hindu Dwelling of Indonesia in the 15th Century. Architecture 2023, 3, 234-257. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3020014

Sulaksono A, Adas YA, Almaimani A. Islamic Influence on the Local Majapahit Hindu Dwelling of Indonesia in the 15th Century. Architecture. 2023; 3(2):234-257. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3020014

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulaksono, Aruji, Yasser Ahmed Adas, and Ayad Almaimani. 2023. "Islamic Influence on the Local Majapahit Hindu Dwelling of Indonesia in the 15th Century" Architecture 3, no. 2: 234-257. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3020014

APA StyleSulaksono, A., Adas, Y. A., & Almaimani, A. (2023). Islamic Influence on the Local Majapahit Hindu Dwelling of Indonesia in the 15th Century. Architecture, 3(2), 234-257. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture3020014