Abstract

One of the highest risk groups the highest during COVID-19 were chronic patients. In addition to being a population at risk, in the lockdown they had to combine the pandemic with their own disease. Through a qualitative study of visual–emotional analysis, the perception of patients and their social environment (immediate support network) about the domestic confinement in Spain was requested during the State of Alarm in the Spring of 2020. For this, 33 participants filled out an online questionnaire with narratives and images describing their experiences. They were asked to share their experiences about quarantine from several perspectives of the housing spaces: the workplace (or alternatively, if they did not work, the most used occupational space), the least pleasant spaces or aspects of the dwelling and the most pleasant or comfortable area. The results suggested the importance for participants of natural and adequate lighting in spaces and tidiness, with both being linked to well-valued spaces. Moreover, rest was the activity most undertaken, for those who did not telework. Likewise, the narratives provided by participants were mostly positive, despite their condition, maybe due to their own coping with the disease. Dwellings were the adaptive means to tackle the situation of physical isolation as a place of protection against an external threat. The living room and bedrooms were chosen as the most prominent places. The characteristics of the dwellings conditioned the experiences lived during the quarantine of chronic patients.

1. Introduction

At the end of 2019, a new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was detected. Within six months, its worldwide transmission provoked a pandemic [1], with 10,000,000 confirmed cases and 500,000 deaths, causing a health crisis unusual in the last century [2].

Shortly after the end of the State of Alarm in Spain, on 2 July 2020, a total of 249,000 people diagnosed and more than 28,000 deaths were already quantified. Spain became one of the European countries most affected by COVID-19 [3].

Due to the health competencies of the Autonomous Communities (regions) in Spain, they dealt with COVID-19 unevenly. At the national level, the National Health System suffered due to the scarcity of resources, equipment and personnel in a climate of restlessness and uncertainty in health services. Faced with the threat generated shortly before the Spring of 2020, the national government decreed the State of Alarm, which led to mandatory confinement in homes, except for force majeure or attention to essential services, as well as the closure of all schools [4,5].

In Europe, the main causes of mortality and morbidity are due to chronic diseases. Many of them are related to population aging, lifestyle and genetic predisposition. The management of chronic diseases is a priority for policy makers and the scientific community [6]. In Spain, almost half of men (49.3%) and more than a half of women (59.1%) over 15 years old develop some disease or chronic health problem [7].

Non-pharmacological interventions were the main measures taken by most countries to combat the spread of COVID-19 during the first waves of infection [8]. The confinement forced citizens to remain in their homes [9]. In the case of Spain, as a result of Royal Decree 463/2020, due to the health emergency situation, the government adopted this measure, especially recommended for vulnerable groups (elderly people [10], chronic [11] and immunosuppressed patients) [12]. Indeed, quarantine was especially impactful on these segments of the population [13], standing out as children and young [14,15], elderly [16] and chronic patients [17]. In the latter, the feeling of insecurity and uncertainty and their own fears of contagion were joined by other episodes of anxiety and discomfort due to both the fear of a greater vulnerability and of their already deteriorated health [18], as well as a lack of health support [19] and social support networks, based on family, friends or closest contacts [20].

By establishing compulsory confinement for the population, the home became the main refuge [21] and the only space available and safe for citizens [22]. All daily activity began to take place at home [23], causing alterations in the habits and consumption of dwellings [24,25,26,27,28]. It also meant a change in the way of working [29,30] or studying [31]. All this highlighted the importance of the characteristics of the house, taking into account the unusual situation of confinement.

Housing is defined as an intermediate determinant related to social inequalities in health, according to the conceptual framework adapted from the WHO by Vásquez-Vera et al. In fact, it was supposed to be a key factor during the first wave. Domestic spaces changed their uses and meanings for their dwellers, turning out to be the center of operations for families [32]. Housing during the pandemic became shelter and, especially for vulnerable groups, such as the chronically ill among others [33], constituted a basic human need, a structure or physical space. The home is a safe haven that protects from external threats [34] and is the preferred place to be cared for when receiving palliative care [35]. Likewise, 85% of chronic patients who receive home care have a longer life expectancy than patients who do not [36].

The built environment design directly affects the habitability of homes [26]. Moreover, the home is associated with emotions, memories and comfort. For many people, leaving home is disturbing and depressing [37]. Having stability in the home reduces the stress produced in the search for a home and in the adaptation to the place itself [38]. In this sense, several studies reported mental health consequences for chronic patients during confinement, such as stress, anxiety and depression [39,40,41,42] or managing their own disease during the pandemic [43,44,45,46,47]. The perception of patients during a situation as extreme as COVID-19 isolation helps to understand the interactions between people and domestic environments through their testimonies and emotions experienced. COVID-19 meant an alteration to their lifestyles for this group; they had to stay home longer than usual [48], had greater difficulty with health care [49] and were even affected in their own care [17,50]. This generated inequalities among chronic patients themselves in access to resources, support and health services [51].

However, there are fewer studies that address confinement and housing in chronic patients from a qualitative perspective. Considering that the home was the refuge of all people, this study is relevant to provide findings that allow knowledge of the the perception of patients in an adverse situation, such as confinement due to COVID-19.

The aim of this qualitative study is to understand the perception by chronic patients of their environment during the lockdown, particularly their occupational spaces and other aspects related to the home, the place that was the refuge for all confined people. Their experiences might contribute to develop strategies and public policies on how to prevent certain situations (such as social isolation or difficulties on health-care attention), or at least to make up contingence plans to copy for health emergencies such as this one.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Visual Methods in Qualitative Research

There is an increasing interest and acceptance of qualitative research in the health sciences [52] and more and more reputable medical journals are publishing these qualitative studies [53]. Qualitative research is considered necessary for public health. It allows the study of people’s health and disease [54].

Qualitative research has been evolving in reducing the time and cost of studies, using new techniques to accelerate the processes of data collection and analysis [55]. Among the different methods used in qualitative research are visual methods. Visual methods are used to interpret and understand images, which can be collected in different ways, such as photographs, drawings and paintings, among other media. Visual methodologies have evolved in recent years and are accepted tools in qualitative research. In addition, their use has spread in different disciplines [56,57,58], including health research.

Visual methods are useful, since they enhance findings by uncovering more detailed information that cannot be obtained by other verbal and written methods. Their versatility allows them to be applied when working with any population [56].

Among the different image-based methods to allow participants to express themselves, Photovoice stands out [59]. Photovoice is characterized by its versatility, since its methodology can be adapted to different contexts. It also uses a participatory research approach, promotes individual reflection and does not require direction by the researcher. Images are combined with the narrative of participants [31,60,61]. The Photovoice originally promotes giving “voice” to those who usually do not have it, also eliciting community debate for critical awareness, detection of shortcomings and the proposal of solutions. During the confinement, an adaptation was elaborated, given the circumstances, urging participants to reflect individually.

2.2. Sentiment Analysis to Understand Emotions

Sentiment analysis is a field of research to analyze and understand human emotions [62,63,64]. It uses natural language processing techniques and text analysis, allowing the detection of emotional content in narratives. Through sentiment analysis, two different metrics can be obtained: one is the polarity and the other the subjectivity of the analyzed texts [62]. Polarity analysis allows the identification of the sentiments in a text [57]. There are three types of polarity: positive, negative and neutral [31]. This approach allows us to assess those emotions perceived from the participants’ narratives.

3. Materials and Methods

To carry out the research, the methodology proposed by Cuerdo-Vilches and Navas Martín [31] was called visual–emotional analysis. This methodology was characterized by combining two qualitative methods: on the one hand, the collection of images and narratives from the participants through an online data collection platform, as a methodological adaptation of the Photovoice technique. On the other hand, the use of sentiment analysis and text mining for the analysis of textual content, where the intention was not only to making the photograph (as an explanatory argument), but also to analyze the mood and other potentially implicit emotional aspects in the messages by their authors, through their polarity.

This kind of approach usually finds relevant the personal interaction in data collection, by the uniqueness of the context. Thus, it was necessary to reinvent the original participatory methodological approach, adapting data collection techniques [65]. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic circumstances, social research techniques without a physical presence were appropriate [66].

In addition, participants were asked for sociodemographic data and information on their condition as patients. Next, they were asked to share photographs taken by themselves, on four specific issues (the first two options being exclusive depending on whether the person teleworked or not). The topics they were asked for photographs about were the following:

- -

- An image that defined the teleworking space at home (T1), or, failing that, an image that represented the space in which they spent most of their time (T2);

- -

- An image that reflected the least pleasant aspect of their home (T3);

- -

- An image that showed the most comfortable domestic space for them (T4).

Likewise, they were asked to tag the images with three keywords per image, to categorize them. A written narrative contextualization was also requested, answering, for each of the images, the following five open questions:

- -

- What do you see in the picture? (Q1);

- -

- What is happening in the picture? (Q2);

- -

- Why did you take this picture? (Q3);

- -

- What does this picture express about your life now, during confinement? (Q4);

- -

- What message could this picture give to other people, to improve their lives? (Q5).

This contextualization allows the researchers to categorize the images according to the intentions of the participants as well as the subsequent content analysis and finally the mixed analysis.

3.1. Participants and Procedures

For the recruitment of participants (Table 1), a purposive non-probabilistic sampling was taken, with the collaboration of the Más-Que-Ideas Foundation. This foundation is a non-profit organization whose mission is to improve, promote and contribute to a change in the health sector, focused on improving the quality of life of patients and their environment. The foundation has a wide network of contacts between different organizations and patient associations. With their intermediation, the dissemination was carried out through the email and social networks of the foundation itself. The data collection period was established from 20 May to 4 June, when the State of Alarm decreed by the Spanish government was in force [67], so the population was still confined to their homes.

Table 1.

Sample of participants in the qualitative questionnaire.

The inclusion criteria to participate were as follows: to be adults (over 18) and to be patients or close to one of them, as cohabitants in the same household (joined a patient association).

Participation had the approval of the foundation. In addition, online consent was explicitly obtained from the participants themselves, accessing the qualitative questionnaire after reading a study description and the conditions of participation. In total, 33 responses (photos and texts) were validated, according to Table 1.

3.2. Data Collection

The online platform SurveyMonkey® was used for data collection. This platform allowed the questionnaire to be completed through any electronic device with a Web browser and an available Internet connection. One of the main characteristics of the platform was its ease for directly taking photos, allowing the participants to take them using their own smartphones, in real time (while they finished filling in the remaining fields of the questionnaire).

3.3. Data Analysis

The images provided by the participants were analyzed by selecting the most relevant ones and categorizing them according to the topics. The photo selection took into account the intentionality of the participants as described in the answers to the open-ended questions. The relevance of the materials was established according to the relationship between the general and specific research objectives, following the content analysis carried out. The contents were coded and then categorized according to similarities and differences found in the photos.

A content analysis from narratives was also carried out. On the one hand, a word frequency cloud was performed to quantify the terms that showed the highest frequency. For this purpose, empty words were eliminated and the root word was used for further analysis. On the other hand, the most significant verbatims were selected. Finally, a sentiment analysis was performed to know the polarity from the participants’ testimonies, being the three polarity types, as indicated above.

For qualitative data analysis, the NVIVO release 1.3.1 program was used. For the sentiment analysis, the programming software R version 4.0.3 was applied.

4. Results

Of the total of 33 participants (Table 1), 30.3% were men (n = 10) and 69.7% were women (n = 23). Additionally, 60.6% (n = 20) stated that they were chronic patients, compared to 36.4% (n = 12) who answered they were not. Almost the total, 93.9% (n = 31) stated that they belonged to some patient association, compared to 6.1% (n = 2) who answered that they did not.

Regarding the contents, a total of 67 images, 171 labels and 334 written answers to the open questions related to the photos were collected. The thematic distribution of images was as follows: 11 images on teleworking (T1); 22 on other occupational spaces (T2) (thus, a third of the total sample were teleworking, and the remaining people spent their time in other activities); 20 on the least pleasant domestic aspect/space (T3); and 14 pictures on the most comfortable domestic space (T4).

4.1. Visual Analysis

4.1.1. Selection of Photos

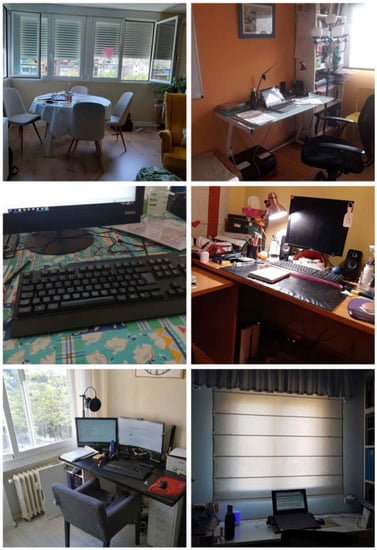

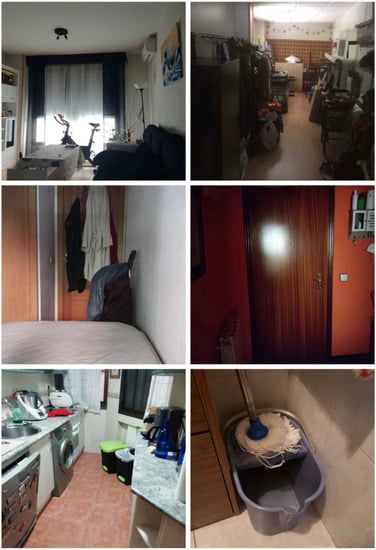

Below, a selection of 24 images from participants is presented, as evidence of the quarantine experiences from several perspectives for domestic spaces: teleworking spaces (T1) (Figure 1), other occupational spaces (T2) (Figure 2)—if they declared they did not telework, less pleasant domestic aspects (T3) (Figure 3), and more pleasant spaces (T4) (Figure 4), provided by participants.

Figure 1.

Exclusive or usual spaces for teleworking (T1), many equipped with computers and laptops.

Figure 2.

Spaces where most of the time was spent (occupational areas) (T2), corresponding with different home areas.

Figure 3.

Examples of uncomfortable home aspects (T3), referring to living room and storage room disorders; bedroom size; entrance as barrier; kitchens; and cleaning elements.

Figure 4.

Comfortable spaces (T4), referring to illuminated areas and resting places.

4.1.2. Categorization of Photos

A total of 14 categories and 54 subcategories were obtained from the total of the images analyzed, in relation to teleworking spaces (T1) (Table 2), occupational spaces (T2) (Table 3), less pleasant aspects of homes (T3) (Table 4), and more pleasant areas (T4) (Table 5).

Table 2.

Categorization of picture content related to teleworking spaces (T1).

Table 3.

Categorization of picture content related to occupational spaces (by no teleworking participants) (T2).

Table 4.

Categorization of picture content related to uncomfortable domestic aspects (T3).

Table 5.

Categorization of picture content related to comfortable spaces (T4).

4.2. Textual Analysis

4.2.1. Labels

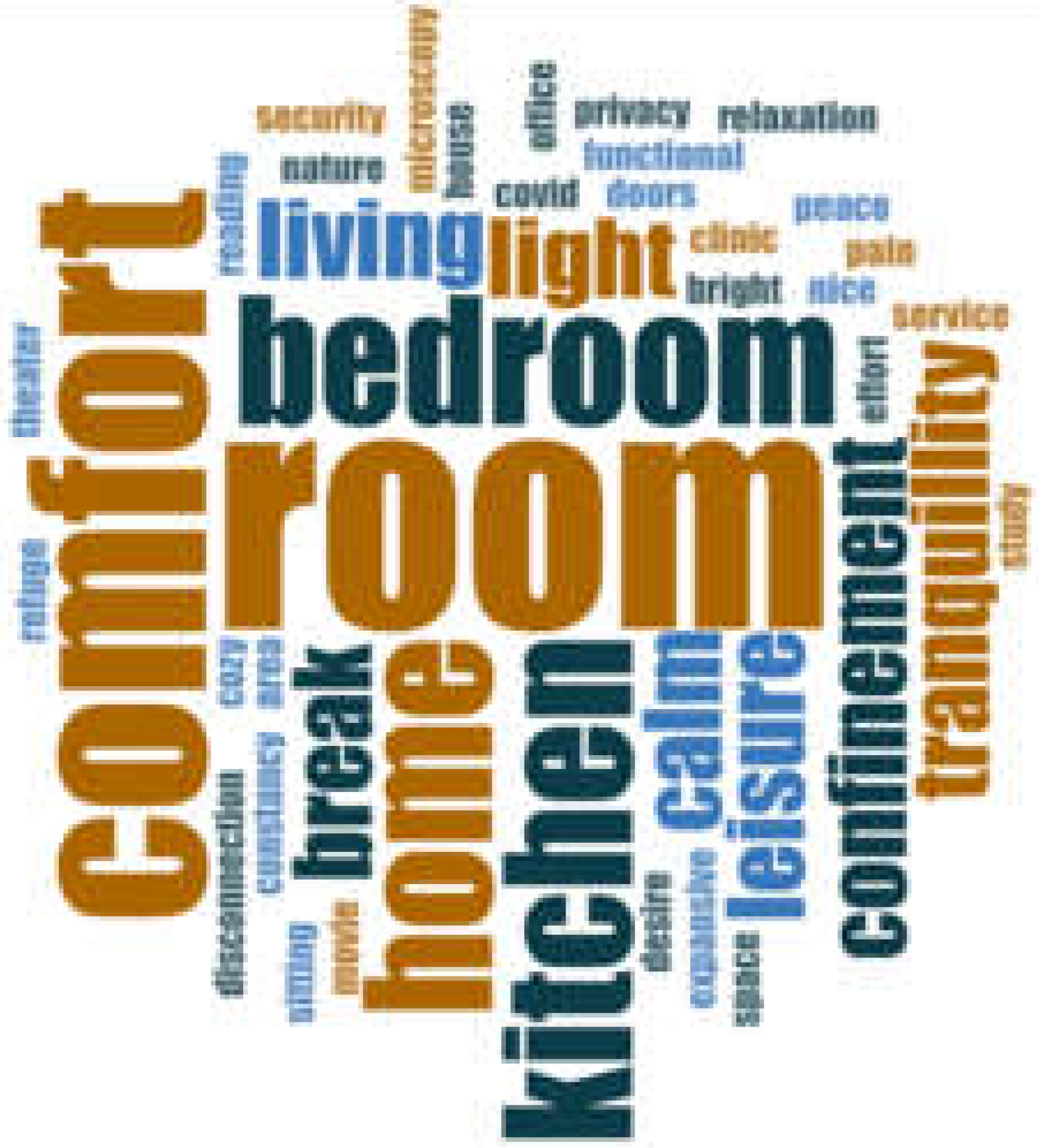

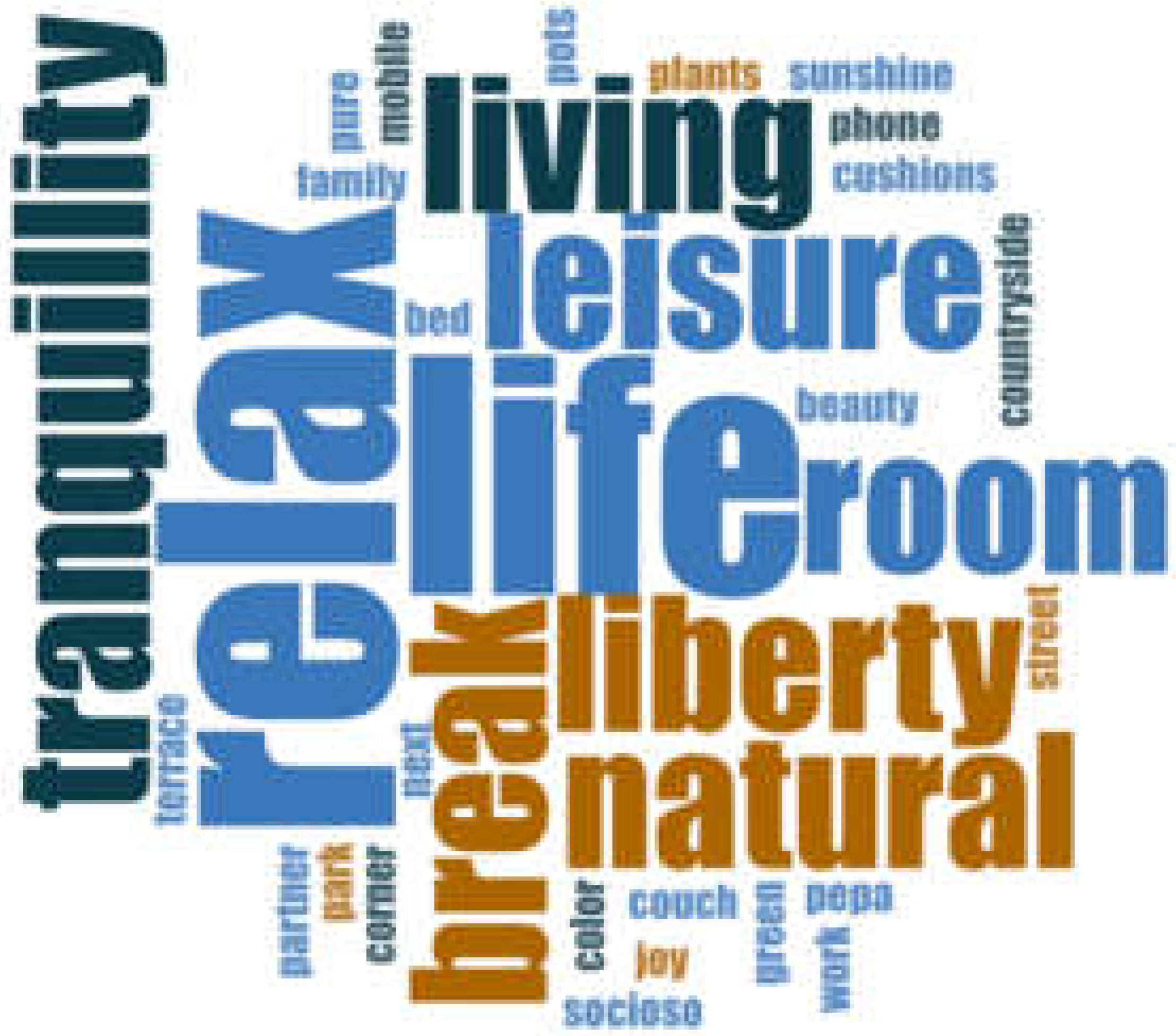

Through the tags, the participants initially categorized their images. Table 6 shows the word clouds from labels provided by participants associated with each type of image.

Table 6.

Word cloud, word frequencies and percentages of the most-repeated tags according to each topic.

4.2.2. Narratives

Through the open questions, the narrative related to the images was obtained from the participants. The answers allowed for contextualization and knowledge of the intentionality provided by them.

4.2.3. Most Relevant Verbatims

To complement the analysis, the most relevant verbatims were selected from the responses to each question. Table 7 shows those related to telework spaces (T1) and other occupational spaces (T2). Table 8 reflects verbatims from the least pleasant domestic aspects (T3) and the most pleasant spaces (T4).

Table 7.

Relevant verbatims for telework (T1) and occupational spaces (T2).

Table 8.

Relevant verbatims from less pleasant domestic aspects (T3) and most comfortable spaces (T4).

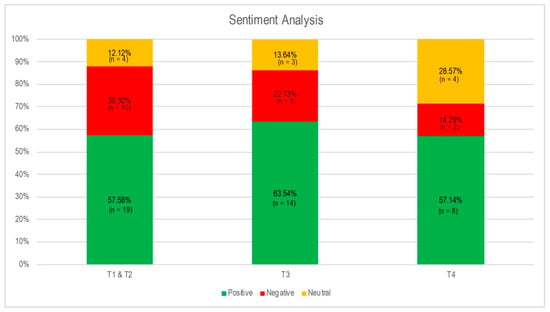

4.2.4. Sentiment Analysis

To find out the polarity (qualification of the emotional charge contained) from answers to the question about what message they could give to other people through their images to improve their lives, a sentiment analysis was carried out. The total number of messages analyzed was 69, of which 69.49% (n = 41) were positive, 28.81% (n = 17) negative and 18.64% (n = 11) neutral. Figure 5 shows the result depending on the image topics: teleworking T1, other occupied spaces T2, less pleasant domestic aspects T3 and the most pleasant spaces T4.

Figure 5.

Sentiment analysis for answers to the question Q5 (messages that they could give through their images to improve others’ lives) for each photo topic.

5. Discussion

According to the results, in this study, the relations that chronic patients and their surroundings established with their dwellings were tackled. Specifically, different spaces and characteristics defining them were analyzed, to see to what extent the interaction due to this confinement was satisfied by adapting, totally or partially, to their lifestyle, habits or routines. The analysis tried to perceive the participants’ way of inhabiting the domestic space in the face of very disruptive and unusual circumstances and from there understand how it was able to affect the emotional state that emerged from their own written impressions through their testimonies.

Regarding the space devoted to working from home, through visual analysis, 6 categories and 14 subcategories were obtained. They highlighted the use of IT equipment (computers and laptops), good lighting, the presence of windows and solar control elements. According to the relevance of these spatial and environmental characteristics, this is aligned to the association of these preferences to the participants’ satisfaction with home design aspects, according to an international study [68]. Some of these parameters, recognized as intervening in people’s health, such as natural ventilation, improving indoor air quality and the entry of sunlight indoors [69,70], were especially outstanding during the COVID-19 pandemic, to avoid or mitigate the harmful effects on health, those derived both from diseases and from a greater presence in the home [71] and thus a greater over-exposure to pollutants and other pathogen agents [24].

In relation to the furniture, it was appreciated as both adequate and inadequate, which could affect ergonomics, generating or worsening illness in the medium–long term with intensive use [72]. The type of space found in the photographs responded to different use degrees, whether exclusive, occasional or shared. This coincided with different similar studies, which also responded to sociodemographic and economic factors or household status [21,22]. This is also in line with the adaptations that people had to make to the design of their houses during confinement [73]. Through textual analysis from narrative, the most frequent words were “comfort”, “house”, “room”, “space” and “study”. This showed that the needs required to adapt to working from home were referenced, according to the qualitative descriptions of the photos, as defined above.

Following the whole analysis, it highlighted that participants had digital skills to carry out their professional activity. This confirms that teleworking favored people with special needs to be able to work efficiently without having to move elsewhere [74]. Moreover, the participants highlighted the importance of separating the workplace from the remaining home spaces, although some participants had to share them, above all to favor family conciliation. This is consistent with other studies, where it is stated that home characteristics conditioned the workspace during the pandemic [29,30]. Issues such as having good lighting favored a pleasant environment and provided visual comfort [75].

Regarding the occupational space for non-teleworkers, 4 categories and 19 subcategories were obtained. These spaces also stood out for having good lighting and maintaining order. Having good lighting was the most predominant factor during the lockdown [76]. With regard to daily household chores, there were several testimonials that dedicated their time to tidying up [77]. For their location, both bedrooms and living rooms were the most photographed. The most perceived activities were aimed at rest, such as reading, or those related to computer use, listening to music or watching television. The most frequent words were “room”, “comfort”, “bedroom”, “home” and “kitchen”. Through the narratives, references were made to a place to disconnect or rest.

Taking into account both the images and the texts, the most used spaces for people who did not telework were places generally perceived as pleasant and comfortable. Their main uses were related to rest, leisure and household chores. The confinement meant a habit change for the general population, producing an increase in the consumption of domestic leisure, such as watching television or listening to music [27,78]. Many people turned to listening to music as a resource to cope with confinement and improve their mood [79,80]. In the case of patients with chronic diseases, it also has a health benefit [81].

In the sentiment analysis from narratives for both working and non-working people, texts about occupational spaces presented the highest percentage (30.30%) of negative messages. This can be interpreted as the confinement context involving an alteration in their lifestyle or in their health benefits [19,21,22,26,27,47], an issue that is perceived negatively in their day-to-day.

In relation to the least pleasant space, 7 categories and 26 subcategories were obtained. Despite being the least pleasant spaces, according to the results in the photo analysis, the spaces showed good lighting and were well organized. Both the size of the place, the location and the views did not show great differences. Regarding the activities reflected, no subcategory stood out more than another. However, certain deficiencies were perceived, contextualized with responses about the need for freedom, company, space and motivation. Through the analysis of narratives, the terms “dark”, “door”, “heat”, “house”, “lack”, “small” and “terrace” stood out. The testimonies offered were associated with emotional reactions of fear and insecurity, in addition to those exposed above.

The pandemic situation for patients with chronic diseases caused an alteration in their routines [48]. Although for some chronic patients confinement meant an improvement in their quality of life, for other people with fewer resources it presented more difficulties [51]. These inequalities were increased between people who, having more resources, were able to adapt their homes due to their illness and those who were not. Instead, the situation of fear and concern was common to all patients [18,82,83]. It is interesting that, when asked about the less pleasant spaces, the participants showed a greater number of positive messages (63.54%). This made us think that, despite the situation they had, patients were able to present positive attitudes, coping with their illness [84] and perhaps reflecting on their life vision and the encouraging prospects for improvement.

Regarding the description of the most pleasant or comfortable domestic spaces, 6 categories and 17 subcategories were obtained. The images shown by participants about these environments also stood out for having adequate lighting and showing orderly spaces. Most of the spaces were indoors, with living rooms being the most frequent locations. Some images reflected views towards green areas and others taken from inside referred to the presence of plants. With regard to the preferences that participants wanted to convey in choosing the images, rest, having plants and the need for leisure stood out. The two most frequent words present in the label analysis were “life” and “relax”. Finally, regarding the analysis of the testimonies, they highlighted the need to be in contact with other people and to rest, mainly through the sofas.

Having views of green areas or plants is related to the need for the well-being and emotional stability that nature transmits [85,86]. The need for relaxation and a change of leisure activities was key during confinement, highlighting art, music or cooking [87,88].

In the COVID-19 lockdown, housing was the adaptive means to cope with the situation of confinement itself. It constituted the place for work, for leisure and for care. Cohabitants had to take advantage of all the space in their home to carry out all the activities. It is interesting to see how each space had a very diverse use among participants but was marked for certain functions within the same home. The living room was featured as the most social place, being the point of rest and disconnection, although some people had to share it to work. In contrast, bedrooms were highlighted as the most reserved places, to disconnect from work or occupation or to isolate oneself in moments of intimacy or concentration. This coincides with other social groups, including the perception of children who telestudied during confinement [31].

This study has several limitations. By the very nature of the qualitative type of study, it cannot be extrapolated to the entire population [89]. However, the origin of data through the use of images and texts can only be approached for analysis from a qualitative perspective. In addition, the qualitative approach allows us to know the behaviors, actions and experiences of the subjects of studies that cannot be carried out through the quantitative approach through statistical analysis, for instance [90].

Another limitation is selection bias, as people without Internet access were excluded [91]. In the study, participants were required to have an Internet connection and a smartphone to take the photos. However, in Spain 93.9% of people between 16 and 74 years old have used the Internet in the last three months [92]. So, the point would be based on a digital competencies bias, since a minimum level of knowledge was required to participate. Finally, there was a lack of control that could be exercised over the respondents [91], since they filled in the questionnaire themselves and thus no interviewers were present. So, any technical doubts they might have had whilst participating could be not solved, although it is common for people with fewer skills to turn to young people to learn how to use technology [93].

6. Conclusions

Housing characteristics conditioned the experiences lived during stay-at-home orders. Adequate lighting was perceived as the most relevant factor by chronic patients, as well as tidiness, although this might be conditioned for two reasons: one due to having to take the photo and the other for a greater availability of time in the home.

The creation of domestic environments to differentiate work and rest spaces was the usual way to favor disconnection or social contact with other household members, according to the needs. Although the house was understood as a safe refuge, fear and insecurity were perceived by participants and transmitted both through the words in narratives and in the constructive or domestic elements reflected: the dwelling access door as a physical and psychological barrier of protection or the photos from terraces and windows stood out, for instance, facing the street physically and even pointing out the invisible enemy, the COVID-19.

The sentiment analysis allowed the emotional level of the testimonies transmitted by participants to be determined. Despite the situation of fear and insecurity, the messages transmitted were mostly positive.

This study contributes with this graphic and testimonial description and its visual–emotional analysis to show an unusual and disruptive experience that enhances the importance of the domestic environment in the health and well-being of people, especially those called vulnerable. Specifically, it delves into the physical, functional and environmental aspects related to housing, as well as those sensory, emotional and psychological perceptions propitiated both by the situation of general uncertainty and individual uncertainty linked to health and by the way of living with them in the home and other factors linked to their social, physical and environmental surroundings. Moreover, it pursues a better understanding of the home environment’s relevance to these segments of the population. The findings of this study can be used to improve the living conditions of these people and specifically under extreme conditions, such as health emergencies, including COVID-19 quarantine.

Author Contributions

All credits are equally attributed to both authors M.Á.N.-M. and T.C.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were previously informed by means of a written informed consent, and they all accepted it. All measures were adopted to ensure anonymous participation, including the instructions to take photographs that did not show any part, element, object or body that directly or indirectly entailed the identification of persons, which was a necessary condition to guarantee it. Otherwise, the photos could be rejected immediately.

Informed Consent Statement

For this study, the Fundación Más que Ideas was previously informed, allowing us to contact the potential patients. An informed consent was requested in the online questionnaire itself, to allow them to decide on the participation. Although this participation was anonymous, each participant accepted and provided informed consent before accessing the questionnaire. Additional information was provided in an information sheet, available for them.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Fundación Más que Ideas (Spain). Furthermore, of course, the authors want to acknowledge the participation of the patients themselves, without whose involvement the study would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Callaway, E.; Ledford, H.; Mallapaty, S. Six months of coronavirus: The mysteries scientists are still racing to solve. Nature 2020, 583, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollán, M.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Oteo, J.; Hernán, M.A.; Perez-Olmeda, M.; Sanmartín, J.L.; Fernández-García, A.; Cruz, I.; de Larrea, N.F.; et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): A nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet 2020, 396, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinazo-Hernandis, S. Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Older People: Problems and Challenges. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2020, 55, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Nicolás Jiménez, J.M.; Recio, L.M.B.; Domínguez, M.T.F.; Cobos, L.P. COVID-19 and Assistance Effort in Primary Care. Atencion Primaria 2020, 52, 588–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, R.; Scheller-Kreinsen, D.; Zentner, A. Tackling Chronic Disease in Europe: Strategies, Interventions and Challenges; WHO Regional Office Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Estado de Salud (Estado de Salud Percibido, Enfermedades Crónicas, Dependencia Funcional). Available online: https://www.ine.es/ss/Satellite?L=es_ES&c=INESeccion_C&cid=1259926692949&p=%5C&pagename=ProductosYServicios%2FPYSLayout¶m1=PYSDetalle¶m3=1259924822888 (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Shah, J.N.; Shah, J.; Shah, J.N. Quarantine, isolation and lockdown: In context of COVID-19. J. Patan Acad. Health Sci. 2020, 7, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Pandemic and lockdown: A territorial approach to COVID-19 in China, Italy and the United States. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, T.C.; Martín, M.N. Indicadores de satisfacción y hábitos de ocupación de los mayores españoles en sus viviendas durante el confinamiento Covid-19. WPS Rev. Int. Sustain. Hous. Urban Renew. 2020, 9-10, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.Á.; Navas-Martín, M. Estudio [COVID-HAB-PAC]: Un Enfoque Cualitativo Sobre El Confinamiento Social (COVID-19), Vivienda y Habitabilidad en Pacientes Crónicos y su Entorno. Paraninfo Digit. 2020, e32075o. Available online: http://ciberindex.com/c/pd/e32075o (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Gobierno de España. Recomendaciones Para Cuidadores y Familiares de Personas Mayores o Vulnerables. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/img/COVID19_Cuidadores_mayores.jpg (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Lauvrak, V.; Juvet, L.K. Social and Economic Vulnerable Groups during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Norwegian Institute of Public Health: Oslo, Norway, 2020.

- De Araújo, L.A.; Veloso, C.F.; de Campos Souza, M.; de Azevedo, J.M.C.; Tarro, G. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. 2021, 97, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, H.; Myers, C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and well-being of children and young people. Child. Soc. 2021, 35, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrawarty, A.; Ranjan, P.; Klanidhi, K.B.; Kaur, D.; Sarkar, S.; Sahu, A.; Bhavesh, M.; Baitha, U.; Kumar, A.; Wig, N. Psycho-Social and Behavioral Impact of COVID-19 on Middle-Aged and Elderly Individuals: A Qualitative Study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntillo, F.; Giglio, M.; Brienza, N.; Viswanath, O.; Urits, I.; Kaye, A.D.; Pergolizzi, J.; Paladini, A.; Varrassi, G. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Chronic Pain Management: Looking for the Best Way to Deliver Care. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 34, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rahimi, J.S.; Nass, N.M.; Hassoubah, S.A.; Wazqar, D.Y.; Alamoudi, S.A. Levels and predictors of fear and health anxiety during the current outbreak of COVID-19 in immunocompromised and chronic disease patients in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional correlational study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danhieux, K.; Buffel, V.; Pairon, A.; Benkheil, A.; Remmen, R.; Wouters, E.; van Olmen, J. The impact of COVID-19 on chronic care according to providers: A qualitative study among primary care practices in Belgium. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.L.; Steinman, L.E.; Casey, E.A. Combatting Social Isolation Among Older Adults in a Time of Physical Distancing: The COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, M.J.; Portillo, M.A.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Oteiza, I.; Navas-Martín, M. Habitability, Resilience, and Satisfaction in Mexican Homes to COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.; Oteiza, I. A Mixed Approach on Resilience of Spanish Dwellings and Households during COVID-19 Lockdown. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo Vilches, T.; Oteiza San José, I.; Navas Martín, M.Á. Proyecto Sobre Confinamiento Social (Covid-19), Vivienda y Habitabilidad [COVID-HAB]. Paraninfo Digit. 2020, 14, e32066o. [Google Scholar]

- De Frutos, F.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Alonso, C.; Martín-Consuegra, F.; Frutos, B.; Oteiza, I.; Navas-Martín, M. Indoor Environmental Quality and Consumption Patterns before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Twelve Social Dwellings in Madrid, Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.Á.; Oteiza, I. Behavior Patterns, Energy Consumption and Comfort during COVID-19 Lockdown Related to Home Features, Socioeconomic Factors and Energy Poverty in Madrid. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán García, A.; Aceituno Nieto, P.; Allende, A.; de Andrés, A.; Arenillas, A.; Bartomeus, F.; Bastolla, U.; Benavides, J.; Cabal, B.; Castillo Belmonte, A.B.; et al. Una Visión Global de La Pandemia COVID-19: Qué Sabemos y Qué Estamos Investigando Desde el CSIC. In Informe Elaborado Desde la Plataforma Temática Interdisciplinar Salud Global/Global Health del CSIC; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (España): Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Martín, M.; López-Bueno, J.A.; Oteiza, I.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T. Routines, Time Dedication and Habit Changes in Spanish Homes during the COVID-19 Lockdown. A Large Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navas-Martín, M.Á.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T. Natural ventilation as a healthy habit during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of the frequency of window opening in Spanish homes. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 65, 105649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.; Oteiza, I. Working from Home: Is Our Housing Ready? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.; March, S.; Oteiza, I. Adequacy of telework spaces in homes during the lockdown in Madrid, according to socioeconomic factors and home features. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M. Confined Students: A Visual-Emotional Analysis of Study and Rest Spaces in the Homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez Priego, K.P. La Vivienda En México de Cara a La Nueva Normalidad. Una Propuesta Aproxiada Espacial. Rev. Acad. Voces Saberes 2021, 1, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Santa María Huertas, R. La Importancia de la Vivienda Para el Cuidado de la Salud en el Perú, en el Marco de la Pandemia COVID-19. Univ. Ricardo Palma. 2020. Available online: https://repositorioslatinoamericanos.uchile.cl/handle/2250/3350555 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Gonyea, J. Housing, Health and Quality of Life. In Handbook of Social Work in Health and Aging; Kaplan, D.B., Berkman, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge, D.; Seow, H.; Sussman, J. Common Components of Efficacious In-Home End-of-Life Care Programs: A Review of Systematic Reviews. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, T.; Arrieta, E.; Lozano, J.E.; Miralles, M.; Anes, Y.; Gomez, C.; Quiñones, C.; Perucha, M.; Margolles, M.; de Caso, J.G.; et al. Atención sanitaria paliativa y de soporte de los equipos de atención primaria en el domicilio. Gac. Sanit. 2011, 25, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarricone, R.; Tsouros, A.D. Home Care in Europe: The Solid Facts; WHO Regional Office Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, S.I.; Mueser, K.T. Schizophrenia. In Handbook of Assessment and Treatment Planning for Psychological Disorders; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 375–414. [Google Scholar]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Dosil-Santamaria, M.; Picaza-Gorrochategui, M.; Idoiaga-Mondragon, N. Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Levels in the Initial Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in a Population Sample in the Northern Spain. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00054020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorrochategi, M.P.; Munitis, A.E.; Santamaria, M.D.; Etxebarria, N.O. Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in People Aged Over 60 in the COVID-19 Outbreak in a Sample Collected in Northern Spain. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luber, R.P.; Duff, A.; Pavlidis, P.; Honap, S.; Meade, S.; Ray, S.; Anderson, S.H.; Mawdsley, J.; Samaan, M.A.; Irving, P.M. Depression, anxiety, and stress among inflammatory bowel disease patients during COVID-19: A UK cohort study. JGH Open 2022, 6, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashakori-Miyanroudi, M.; Souresrafil, A.; Hashemi, P.; Ehsanzadeh, S.J.; Farrahizadeh, M.; Behroozi, Z. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress in patients with epilepsy during COVID-19: A systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 125, 108410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, R.; McCullough, D.; Butler, T.; de Heredia, F.P.; Davies, I.G.; Stewart, C. Sarcopenia during COVID-19 lockdown restrictions: Long-term health effects of short-term muscle loss. Geroscience 2020, 42, 1547–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Martínez, M.M.; Carrera Boada, C.; Madera-Silva, M.D.; Marín, W.; Contreras, M. COVID-19 and Diabetes: A Bidirectional Relationship. Clinica e Investigacion en Arteriosclerosis 2021, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudasama, Y.V.; Gillies, C.L.; Zaccardi, F.; Coles, B.; Davies, M.J.; Seidu, S.; Khunti, K. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: A global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 965–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenneville, T.; Gabbidon, K.; Hanson, P.; Holyfield, C. The Impact of COVID-19 on HIV Treatment and Research: A Call to Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, R.; Pardo, R.; Sora, B.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Luciano, J. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown Measures on Spanish People with Chronic Pain: An Online Study Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Ha, J. Changes in Daily Life during the COVID-19 Pandemic among South Korean Older Adults with Chronic Diseases: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Kaushik, A.; Johnson, L.; Jaganathan, S.; Jarhyan, P.; Deepa, M.; Kong, S.; Venkateshmurthy, N.S.; Kondal, D.; Mohan, S.; et al. Patient experiences and perceptions of chronic disease care during the COVID-19 pandemic in India: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, V.; Lorenzo, M.; Paolo, C.; Sergio, H. Treat all COVID 19-positive patients, but do not forget those negative with chronic diseases. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020, 15, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassieu, L.; Pagé, M.G.; Lacasse, A.; Laflamme, M.; Perron, V.; Janelle-Montcalm, A.; Hudspith, M.; Moor, G.; Sutton, K.; Thompson, J.M.; et al. Chronic pain experience and health inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: Qualitative findings from the chronic pain & COVID-19 pan-Canadian study. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.; Francis, K.; Hegney, D. Qualitative Research in the Health Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: Evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet 2001, 358, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, A. An overview of qualitative research methodology for public health researchers. Int. J. Med. Public Health 2014, 4, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Johnson, G.A. Rapid Techniques in Qualitative Research: A Critical Review of the Literature. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaw, X.; Inder, K.; Kable, A.; Hazelton, M. Visual Methodologies in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 160940691774821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, H. A Literature Review to Evaluate the Choice and Use of Visual Methods. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2012, 11, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, E.; Daykin, N.; Coad, J. Participatory Photography in Qualitative Research: A Methodological Review. Vis. Methodol. 2016, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capewell, C.; Ralph, S.; Symonds, M. Listening to Women’s Voices: Using an Adapted Photovoice Methodology to Access Their Emotional Responses to Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russinova, Z.; Mizock, L.; Bloch, P. Photovoice as a tool to understand the experience of stigma among individuals with serious mental illnesses. Stigma Health 2018, 3, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neogi, A.S.; Garg, K.A.; Mishra, R.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Sentiment analysis and classification of Indian farmers’ protest using twitter data. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2021, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, A.; Paroubek, P. Twitter as a Corpus for Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2010, Valleta, Malta, 19–21 May 2010; European Language Resources Association (ELRA): Paris, France, 2010; pp. 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Della Pietra, S.A.; Della Pietra, V.J. A Maximum Entropy Approach to Natural Language Processing. Comput. Linguist. 1996, 22, 39–71. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Amarillo, S.; Fernández-Agüera, J.; González, M.M.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T. Overheating in Schools: Factors Determining Children’s Perceptions of Overall Comfort Indoors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernán-García, M.; Lineros-González, C.; Ruiz-Azarola, A. How to Adapt Qualitative Research to Confinement Contexts. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 35, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobierno de España. Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de Marzo, por el que se Declara el Estado de Alarma Para la Gestión de la Situación de Crisis Sanitaria Ocasionada Por El COVID-19, Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain. 2020. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2020/03/14/463/con (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Vasquez, N.G.; Amorim, C.N.D.; Matusiak, B.; Kanno, J.; Sokol, N.; Martyniuk-Peczek, J.; Sibilio, S.; Scorpio, M.; Koga, Y. Lighting conditions in home office and occupant’s perception: Exploring drivers of satisfaction. Energy Build. 2022, 261, 111977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Directrices de la OMS Sobre Vivienda y Salud: Resumen de Orientación; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/279743/WHO-CED-PHE-18.10-spa.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Sáenz de Tejada, C.; Daher, C.; Hidalgo, L.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Vivienda y Salud Características y Condiciones de la Vivienda; Diputación de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2021.

- Muñoz-González, C.; Ruiz-Jaramillo, J.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Joyanes-Díaz, M.; Vega, L.M.; Cano-Martos, V.; Navas-Martín, M. Natural Lighting in Historic Houses during Times of Pandemic. The Case of Housing in the Mediterranean Climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerding, T.; Syck, M.; Daniel, D.; Naylor, J.; Kotowski, S.E.; Gillespie, G.L.; Freeman, A.M.; Huston, T.R.; Davis, K.G. An assessment of ergonomic issues in the home offices of university employees sent home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Work 2021, 68, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawad, A. Adapting and Interacting with Home Design during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Des. J. 2021, 11, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, N.W.; Linden, M.A.; Bricout, J.C.; Baker, P.M. Telework rationale and implementation for people with disabilities: Considerations for employer policymaking. Work 2014, 48, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Králiková, R.; Lumnitzer, E.; Džuňová, L.; Yehorova, A. Analysis of the Impact of Working Environment Factors on Employee’s Health and Wellbeing; Workplace Lighting Design Evaluation and Improvement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabi, M.; Yazdanfar, S.-A.; Hosseini, S.-B. COVID-19 and healthy home preferences: The case of apartment residents in Tehran. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlak, S.; Cakiroglu, O.C.; Gul, F.O. Gender roles during COVID-19 pandemic: The experiences of Turkish female academics. Gender, Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 461–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, N.; Hollander-Shabtai, R. Music and COVID-19: Changes in uses and emotional reaction to music under stay-at-home restrictions. Psychol. Music. 2021, 50, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabedo-Mas, A.; Arriaga-Sanz, C.; Moliner-Miravet, L. Uses and Perceptions of Music in Times of COVID-19: A Spanish Population Survey. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 606180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, F.S.; Lessa, J.P.A.; Delmolin, G.; Santos, F.H. Music Listening in Times of COVID-19 Outbreak: A Brazilian Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pothoulaki, M.; MacDonald, R.; Flowers, P. The Use of Music in Chronic Illness: Evidence and Arguments. In Music, Health, and Wellbeing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Bala, R.; Srivastava, A.K.; Mishra, A.; Shamim, R.; Sinha, P. Anxiety, obsession and fear from coronavirus in Indian population: A web-based study using COVID-19 specific scales. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2020, 7, 4570–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, G.; Gerritsen, L.; Duijndam, S.; Salemink, E.; Engelhard, I.M. Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, A.; Ostermann, T.; Neugebauer, E.A.; Heusser, P. Adaptive coping strategies in patients with chronic pain conditions and their interpretation of disease. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesters, Y.; Smolders, K.C.H.J.; Kamphuis, J.; De Kort, Y.A.W. Housing, Natural Light and Lighting, Greenery and Mental Health. Tijdschr. Psychiatr. 2020, 62, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Lercher, P.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Stoyanov, D.; Petrova, N.; Novakov, S.; Dimitrova, D.D. Does greenery experienced indoors and outdoors provide an escape and support mental health during the COVID-19 quarantine? Environ. Res. 2020, 196, 110420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, O.; Haseki, M.I. Positive Psychological Impacts of Cooking During the COVID-19 Lockdown Period: A Qualitative Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 635957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, K.F.; Fine, P.A.; Friedlander, K.J. Creativity and Leisure During COVID-19: Examining the Relationship Between Leisure Activities, Motivations, and Psychological Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 609967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.C. Successful Qualitative Health Research: A Practical Introduction; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo Menéndez, M.; Finkel, L. Encuestas Por Internet y Nuevos Procedimientos Muestrales. Panor. Soc. 2019, 30, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta Sobre Equipamiento y Uso de Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en los Hogares; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- Moreno Becerra, T.A. Comunicación Móvil y Adulto Mayor: Exclusión y Uso Desigual de Dispositivos Móviles. Perspect. Comun. 2016, 9, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).