Disease Localization and Bowel Resections as Predictors of Vitamin B12 and Vitamin D Status in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Institutional Review Board (IRB) Statement

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Data Collections

2.4. Sample Size Considerations

2.5. Definitions

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

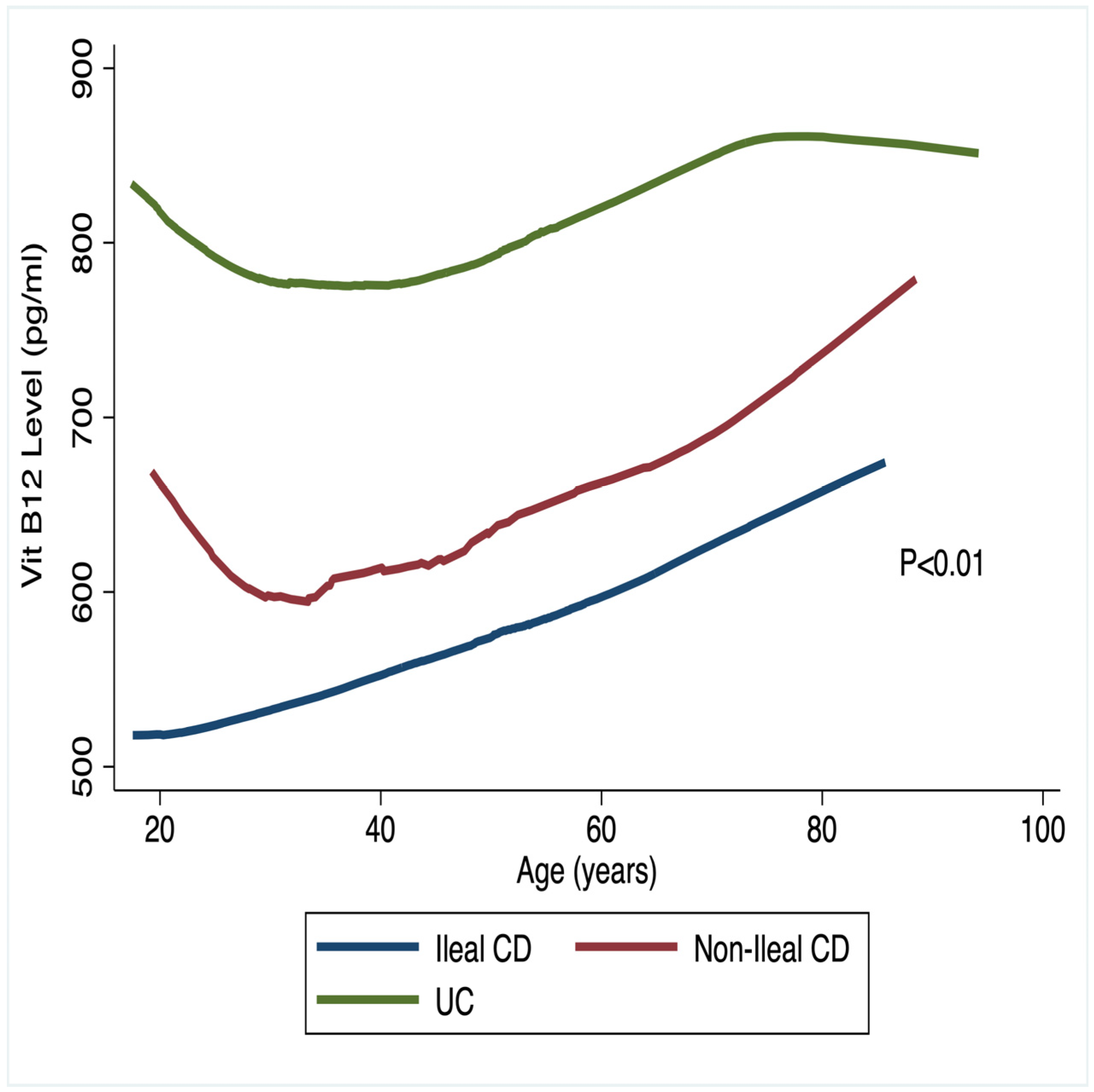

3.1. Micronutrient Status and IBD Lesion Localization

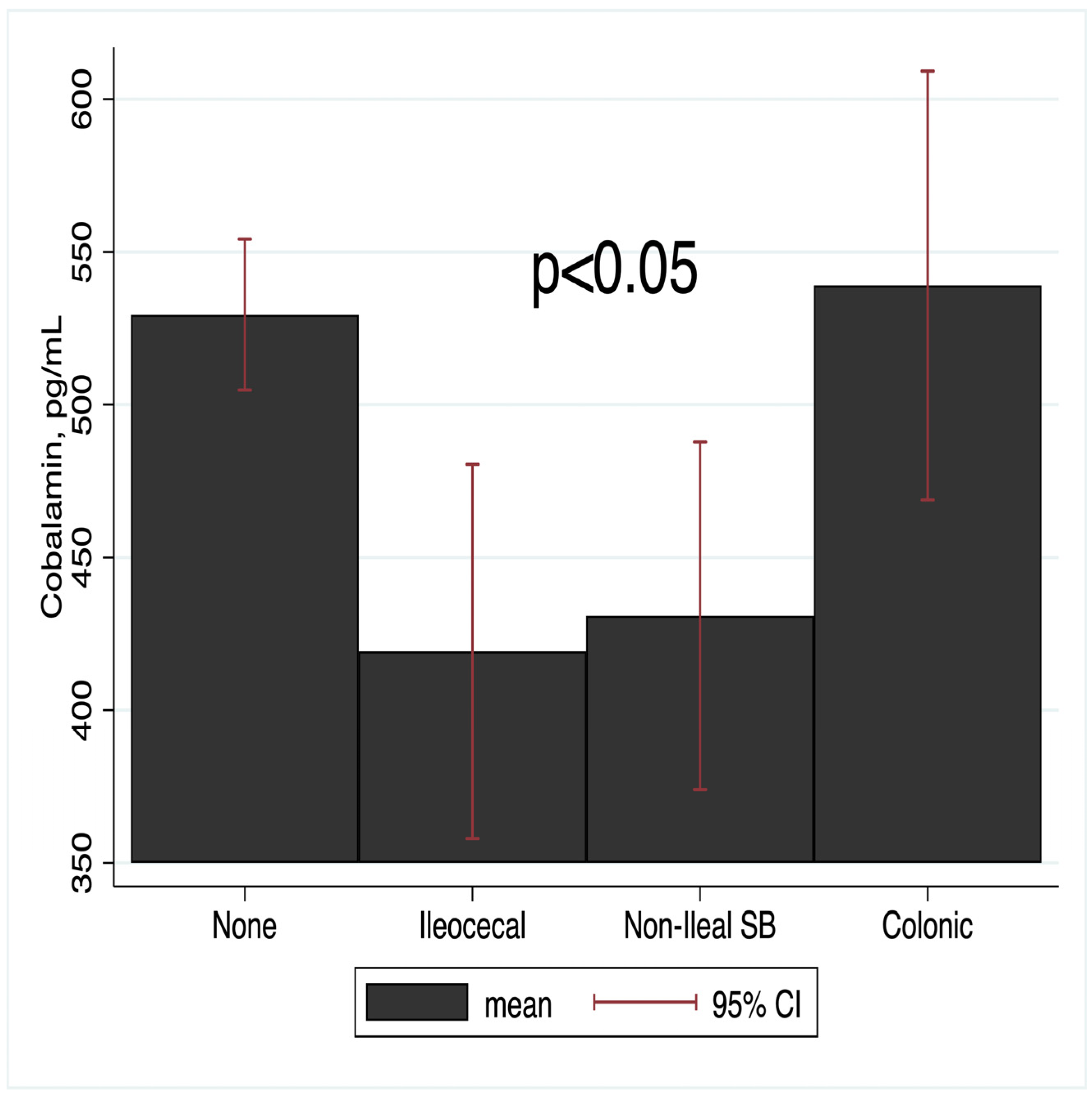

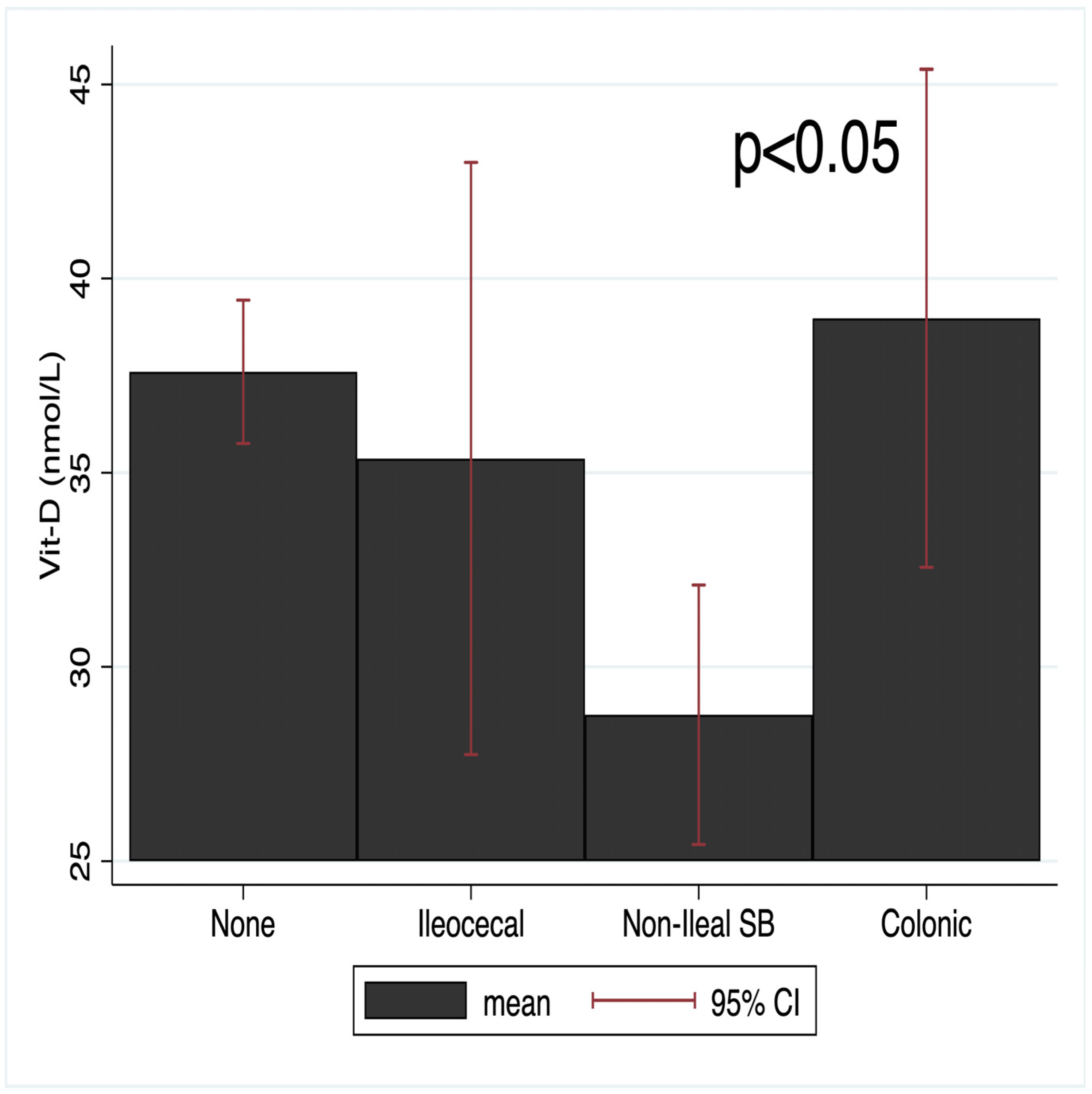

3.2. Micronutrient Status and Bowel Resection Status

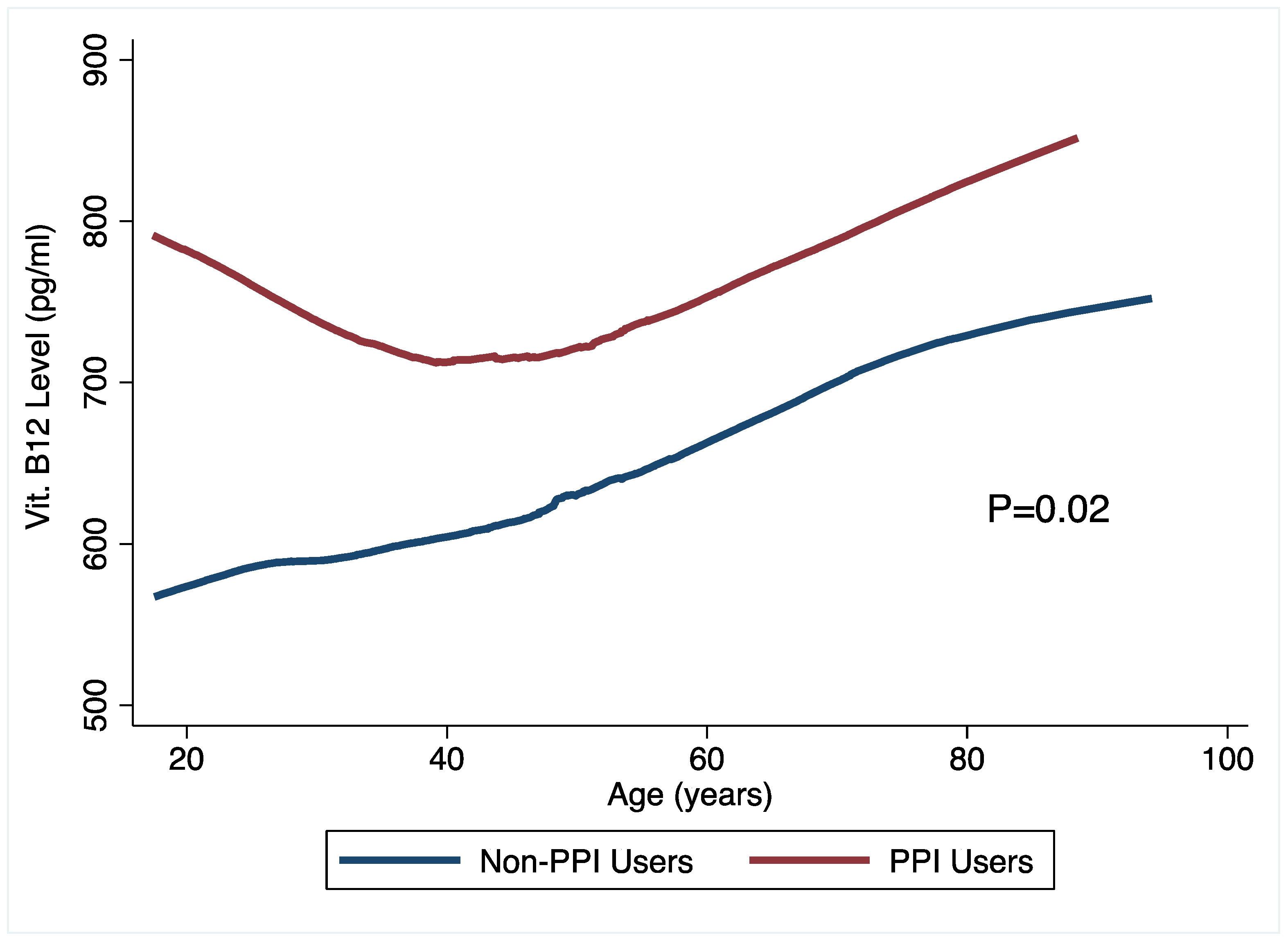

3.3. Micronutrient Status and PPI Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, B.P.; Ahmed, T.; Ali, T. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathophysiology and Current Therapeutic Approaches. In Gastrointestinal Pharmacology; Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 115–146. [Google Scholar]

- Weisshof, R.; Chermesh, I. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrend, C.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Mortensen, P.B. Vitamin B12 absorption after ileorectal anastomosis for Crohn’s disease: Effect of ileal resection and time span after surgery. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1995, 7, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, O.H.; Hansen, T.I.; Gubatan, J.M.; Jensen, K.B.; Rejnmark, L. Managing vitamin D deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vítek, L. Bile acid malabsorption in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacMaster, M.J.; Damianopoulou, S.; Thomson, C.; Talwar, D.; Stefanowicz, F.; Catchpole, A.; Gerasimidis, K.; Gaya, D.R. A prospective analysis of micronutrient status in quiescent inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neale, G. B12 binding proteins. Gut 1990, 31, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, F.; Samman, S. Vitamin B12 in health and disease. Nutrients 2010, 2, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccuzzi, L.; Infante, M.; Ricordi, C. The potential therapeutic role of vitamin D in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 4678–4687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Khalili, H.; Higuchi, L.M.; Bao, Y.; Korzenik, J.R.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Richter, J.M.; Fuchs, C.S.; Chan, A.T. Higher predicted vitamin D status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, S.P.; Hvas, C.L.; Agnholt, J.; Christensen, L.A.; Heickendorff, L.; Dahlerup, J.F. Active Crohn’s disease is associated with low vitamin D levels. J. Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, e407–e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Nugent, Z.; Singh, H.; Shaffer, S.R.; Bernstein, C.N. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use Before and After a Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashash, J.G.; Elkins, J.; Lewis, J.D.; Binion, D.G. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diet and Nutritional Therapies in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Song, X.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, C.; Xia, J.; Zou, D.; Liu, J.; Yin, F.; Yin, L.; Guo, H.; et al. ABCG2 plays a central role in the dysregulation of 25-hydrovitamin D in Crohn’s disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 118, 109360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwuzo, S.; Boustany, A.; Khaled Abou Zeid, H.; Hitawala, A.A.; Almomani, A.; Onwuzo, C.; Lawrence, F.; Monteiro, J.M.; Ndubueze, C.; Asaad, I. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Patients Using Proton-Pump Inhibitors: A Population-Based Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e34088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, J.R.; Schneider, J.L.; Zhao, W.; Corley, D.A. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA 2013, 310, 2435–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, A.; Jena, A.; Jearth, V.; Dutta, A.K.; Makharia, G.; Dutta, U.; Goenka, M.; Kochhar, R.; Sharma, V. Vitamin B12 deficiency and use of proton pump inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 17, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losurdo, G.; Caccavo, N.L.B.; Indellicati, G.; Celiberto, F.; Ierardi, E.; Barone, M.; Di Leo, A. Effect of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use on Blood Vitamins and Minerals: A Primary Care Setting Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakeman, M. A Literature Review of the Potential Impact of Medication on Vitamin D Status. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 3357–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-Ugarriza, R.; Palacios, G.; Alder, M.; González-Gross, M. A review of the cut-off points for the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency in the general population. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2015, 53, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headstrom, P.D.; Rulyak, S.J.; Lee, S.D. Prevalence of and risk factors for vitamin B(12) deficiency in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, C.E.; Globig, A.M.; Busse Grawitz, A.; Bettinger, D.; Hasselblatt, P. Seasonal variability of vitamin D status in patients with inflammatory bowel disease—A retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frigstad, S.O.; Høivik, M.; Jahnsen, J.; Dahl, S.R.; Cvancarova, M.; Grimstad, T.; Berset, I.P.; Huppertz-Hauss, G.; Hovde, Ø.; Torp, R.; et al. Vitamin D deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease: Prevalence and predictors in a Norwegian outpatient population. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parva, N.R.; Tadepalli, S.; Singh, P.; Qian, A.; Joshi, R.; Kandala, H.; Nookala, V.K.; Cheriyath, P. Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency and Associated Risk Factors in the US Population (2011–2012). Cureus 2018, 10, e2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, B.; Donnelly-VanderLoo, M.; Watson, T.; O’Connor, C.; Madill, J. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy and vitamin B(12) status in an inpatient hospital setting. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman, T.T.; Cohen, E.; Sochat, T.; Goldberg, E.; Goldberg, I.; Krause, I. Proton pump inhibitor use and its effect on vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels among men and women: A large cross-sectional study. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 364, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean Age (range) | 47 (17–94) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 362 (63) |

| Male | 208 (37) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 522 (91) |

| Other | 49 (9) |

| Medications used, n (%) | |

| PPI | 254 (44) |

| Corticosteroid | 286 (50) |

| Antibiotic | 237 (42) |

| Biologic | 332 (58) |

| Immunomodulator | 223 (39) |

| Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonist | 74 (13) |

| Micronutrient Status | |

| Vitamin B12 (n = 394) | |

| Mean Concentration (SD, pg/mL) | 643 (514) |

| Prevalence of deficiency (%) | 74 (19) |

| Vitamin D (n = 528) | |

| Mean Concentration (SD, nmol/L) | 37 (18) |

| Prevalence of deficiency (%) | 435 (83) |

| IBD Subtype | |

| UC | 280 (49) |

| Non-Ileal CD | 47 (8) |

| Ileal CD | 241 (43) |

| Surgical resection | |

| No resection | 371 (74.2) |

| Non-Ileal Small Bowel | 23 (4.6) |

| Ileocecal | 56 (11.2) |

| Colonic | 50 (10.0) |

| Non-Ileal CD | Ileal-CD | UC | Global p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B12, pg/mol | 652 (588–817) | 557 (482–631) | 850 (744–957) | 0.0001 |

| Deficiency, n (%) | 5 (12.2) | 49 (24.3) | 10 (10.0) | 0.006 |

| Vitamin D, nmol/L | 36.9 (31.6, 42.1) | 34.9 (33.0, 38.0) | 38.6 (35.5, 40.7) | 0.39 |

| 36 (78.3) | 190 (84.1) | 160 (82.0) | 0.60 |

| Difference in Vitamin B-12 Concentration, pg/mol | Difference in Prevalence of Vitamin B12 Deficiency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect (95% CI) | p-value | Effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Ileal CD vs. Non-ilea CD | −96 (−278, 86) | 0.301 | 2.78 (1.00, 7.75) | 0.051 |

| Ileal CD vs. UC | −293 (−426, −161) | 0.001 | 3.26 (1.47, 7.25) | 0.004 |

| Non-Ileal CD vs. UC | −197 (−393, −2) | 0.047 | 1.18 (0.35, 3.85) | 0.790 |

| Type of Surgery | ALL | CD | UC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Vitamin B12 | |||||||

| No resection | 371 (74.2) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Non-Ileal Small Bowel | 23 (4.6) | 1.47 (0.93, 9) | 0.066 | 2.31 (0.72, 7.42) | 0.158 | - | - |

| Ileocecal | 56 (11.2) | 3.53 (1.5, 7) | 0.001 | 2.54 (1.15, 5.61) | 0.021 | - | - |

| Colonic | 50 (10.0) | 0.56 (0.67, 4.31) | 0.256 | 2.03 (0.70, 5.87) | 0.193 | 1.40 (0.13, 15.54) | 0.785 |

| Vitamin D | |||||||

| No resection | 371 (74.2) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Non-Ileal Small Bowel | 23 (4.6) | 1.40 (0.4, 5.30) | 0.555 | 1.38 (0.36, 5.21) | 0.631 | - | - |

| Ileocecal | 56 (11.2) | 3.35 (1.03, 12.06) | 0.044 | 3.68 (1.01, 13.42) | 0.048 | - | - |

| Colonic | 50 (10.0) | 0.50 (0.28, 1.15) | 0.114 | 0.58 (0.22, 1.50) | 0.261 | 0.53 (0.17, 1.65) | 0.275 |

| Difference in Serum Concentration | Difference in Prevalence of Deficiency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean conc. | Effect (95% CI) | p-value | Prevalence, n (%) | Effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Vitamin B12 (n = 394) | ||||||

| Non-PPI users | 587 (506, 669) | - | 46 (23.5) | 1.00 | ||

| PPI users | 722 (640, 803) | 132.9 (14.7, 251.1) | 0.028 | 28 (14.1) | 0.54 (0.29, 0.98) | 0.043 |

| Vitamin D (n = 528) | ||||||

| Non-PPI users | 36 (34, 38) | - | 250 (85.6) | 1.00 | ||

| PPI users | 38 (35, 40) | 1.65 (−1.80, 5.09) | 0.348 | 185 (78.4) | 0.74 (0.44, 1.25) | 0.263 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barffour, M.A.; Gandhi, M.; Chela, H.; Crawford, S.; Liridon, Z.; Frimpong, K.; Karanja, E.; Luton, K.; Reznicek, E.; Frimpong, H.; et al. Disease Localization and Bowel Resections as Predictors of Vitamin B12 and Vitamin D Status in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 5, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtm5040054

Barffour MA, Gandhi M, Chela H, Crawford S, Liridon Z, Frimpong K, Karanja E, Luton K, Reznicek E, Frimpong H, et al. Disease Localization and Bowel Resections as Predictors of Vitamin B12 and Vitamin D Status in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. International Journal of Translational Medicine. 2025; 5(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtm5040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarffour, Maxwell A., Mustafa Gandhi, Harleen Chela, Serena Crawford, Zguri Liridon, Kwame Frimpong, Elizabeth Karanja, Kevin Luton, Emily Reznicek, Hayford Frimpong, and et al. 2025. "Disease Localization and Bowel Resections as Predictors of Vitamin B12 and Vitamin D Status in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease" International Journal of Translational Medicine 5, no. 4: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtm5040054

APA StyleBarffour, M. A., Gandhi, M., Chela, H., Crawford, S., Liridon, Z., Frimpong, K., Karanja, E., Luton, K., Reznicek, E., Frimpong, H., Bosak, E., & Ghouri, Y. A. (2025). Disease Localization and Bowel Resections as Predictors of Vitamin B12 and Vitamin D Status in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. International Journal of Translational Medicine, 5(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijtm5040054