Abstract

Background: The tooth is a repository of stem cells, garnering interest in recent years for its therapeutic potential. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to test the hypothesis that dental stem cell administration can reduce blood glucose and ameliorate polyneuropathy in diabetes mellitus. The scope of clinical translation was also assessed. Methods: PubMed, Cochrane, Ovid, Web of Science, and Scopus databases were searched for animal studies that were published in or before July 2023. A search was conducted in OpenGrey for unpublished manuscripts. Subgroup analyses were performed to identify potential sources of heterogeneity among studies. The risk for publication bias was assessed by funnel plot, regression, and rank correlation tests. Internal validity, external validity, and translation potential were determined using the SYRCLE (Systematic Review Center for Laboratory Animal Experimentation) risk of bias tool and comparative analysis. Results: Out of 5031 initial records identified, 17 animal studies were included in the review. There was a significant decrease in blood glucose in diabetes-induced animals following DSC administration compared to that observed with saline or vehicle (SMD: −3.905; 95% CI: −5.633 to −2.177; p = 0.0004). The improvement in sensory nerve conduction velocity (SMD: 4.4952; 95% CI: 0.5959 to 8.3945; p = 0.035) and capillary-muscle ratio (SMD: 2.4027; 95% CI: 0.8923 to 3.9132; p = 0.0095) was significant. However, motor nerve conduction velocity (SMD: 3.1001; 95% CI: −1.4558 to 7.6559; p = 0.119) and intra-epidermal nerve fiber ratio (SMD: 1.8802; 95% CI: −0.4809 to 4.2413; p = 0.0915) did not increase significantly. Regression (p < 0.0001) and rank correlation (p = 0.0018) tests indicated the presence of funnel plot asymmetry. Due to disparate number of studies in subgroups, the analyses could not reliably explain the sources of heterogeneity. Interpretation: The direction of the data indicates that DSCs can provide good glycemic control in diabetic animals. However, methodological and reporting quality of preclinical studies, heterogeneity, risk of publication bias, and species differences may hamper translation to humans. Appropriate dose, mode of administration, and preparation must be ascertained for safe and effective use in humans. Longer-duration studies that reflect disease complexity and help predict treatment outcomes in clinical settings are warranted. This review is registered in PROSPERO (number CRD42023423423).

1. Introduction

In 1957, when Thomas et al. published their seminal report on allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplants in humans [1], they opened the door to a revolutionary therapy for leukemia. Since then, stem cell (SC) research in diseases such as retinopathy, dementia, and diabetes mellitus has been advancing by leaps and bounds [2].

It wasn’t until the 1960s, when Friedenstein et al. identified a group of cells providing a scaffold for HSCs within bone marrow, that mesenchymal stem cells came to light [3]. These stromal cells, termed as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) by Caplan in 1991, are plastic, possessing the ability to differentiate into various mesenchymal cell lines and regenerate injured tissues [4]. They migrate to sites of injury and stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of native progenitor cells [5]. MSCs have relatively low immunogenicity [5,6]. Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) molecules are a group of antigen-presenting proteins which are responsible for initiating allogeneic graft rejection [7]. MSC transplants express low levels of HLA class I molecules, do not express HLA class II molecules [7], and remain inconspicuous to cytotoxic T and natural killer (NK) cells [5,8]. In addition, they stimulate the production of regulatory T and B cells [9], a group of specialized lymphocytes that suppress immune response, thereby maintaining homeostasis and immunological tolerance [10].

It is estimated that by 2030, diabetes mellitus will be prevalent in about 643 million adults worldwide [11]. Aside from diseases such as ischemic heart conditions and COVID-19, it was a leading cause of death in 2021, and the global cost for diabetes-related health care was at least USD 966 billion [11]. Uncontrolled diabetes is of grave concern, especially in the post pandemic era, as it complicates recovery and affects the prognosis of almost every infection and disease. Type 1 diabetes (T1DM) is caused by autoimmune destruction of islets of Langerhans, resulting in endogenous insulin deficiency [12]. Its pathogenesis is influenced by genetic as well as environmental factors and is most commonly diagnosed in adolescents and young adults [12]. Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is characterized by insulin resistance and the inability of islet cells to produce sufficient insulin to compensate, leading to relative insulin deficiency [12]. It is most commonly diagnosed in middle aged adults and is often associated with obesity [12].

Approximately 50% of diabetic adults are eventually afflicted with polyneuropathy (DPN) [11]. It is characterized by axonal degeneration [13,14] caused by pro-inflammatory cytokine-releasing metabolic cascades, which result in structural and functional changes in endoneurial and microvascular tissues [15,16]. DPN is associated with a high risk for foot ulcers and lower limb amputations [16]. Treatment involves regular screening, stringent glycemic control, and pain alleviation [16].

Islet cell transplantation is an alternative therapy for diabetes mellitus, but is associated with the risk of graft rejection and paucity of donor sources [14]. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs) are capable of differentiating into insulin secreting cells [8]. However, retrieval is often accompanied by pain [8], nerve injury [17], and low cell yield upon harvest [8]. Hence, the umbilical cord, placenta, and teeth, which are discarded after removal, have gained ground as alternate MSC reserves [8,17].

The primitive tooth organ and supporting structures are formed by complex interactions of the neural crest with epithelial and mesodermal components [18]. The dental follicle and papilla formed in turn give rise to gingiva, periodontal ligament, and dental pulp [8]. Hence, these ectomesenchymal tissues retain the stemness of neural crest cells [8,18]. There are six types of stem cells of dental origin (DSCs) that have been isolated and characterized so far: dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), stem cells from the pulps of human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED), dental follicle precursor cells (DFPCs), stem cells from apical papilla (SCAP), periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), and gingival mesenchymal stem cells (GMSCs) [8,9,18]. SCs harvested from these tissues are able to transdiffferentiate into neuronal-like and pancreatic β cells [8,9,17], and this ability can be traced back to the neural crest and to similarities between neuronal and pancreatic β cells [8].

Following extraction, exfoliation, or gingival surgery, ideally under sterile conditions and minimal trauma, the tooth or periodontal tissue is preserved to maintain the viability of stem cells until their retrieval [19]. After the surface of the tooth is cleansed, the tissue is retrieved from the tooth, minced, and digested in collagenase [19]. The cells undergo neutralization and centrifugation [19]. They are then trypsinized and can differentiate into insulin releasing islet-like cells after undergoing several passages in culture [19]. The stem cell activity in a tooth varies, and is contingent on factors such as donor age, tooth morphology, DSC type, tissue health, and conditions during retrieval [20]. For instance, in one study, six lines of SCs were obtained from the pulps of six deciduous teeth of children aged 4–8 years, whereas two DPSC lines were obtained from six permanent teeth of donors aged 55–67 years [20].

DSCs have more robust population doubling rates than do BMMSCs [8]. They are also able to differentiate into odontogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic, adipogenic, and epithelial cell lineages under specific conditions, thus possessing the potential for application in the regeneration and repair of tissues that arise from all three germ layers [19,21]. There is ongoing research for their use in pulp and dentin regeneration, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and liver fibrosis, among other diseases [8,18,20,21].

DSCs can serve as replenishable sources of islet cells; hence, they hold allure in diabetology. Studies have been done to elucidate their effects; however, to our knowledge, a study which systematically reviews and quantifies existing data on the use of various DSCs in diabetes mellitus has not yet been undertaken. Hence, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to appraise the extent of evidence in relation to the focused question: “Do dental stem cells reduce blood glucose and alleviate polyneuropathy in diabetic animals compared to animals administered with saline or vehicle?” In addition to testing this hypothesis, we discern the scope of translation of this novel therapy to humans.

2. Methods

This systematic review was reported in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA 2020 statement [22], an updated version of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis, which is a set of guidelines used to improve the transparency and quality of systematic reviews (PRISMA 2020 checklists are available as Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). The review is registered in PROSPERO, an international database of systematic reviews (registration number CRD42023423423).

2.1. Search Strategy

The search was defined to identify studies that evaluated the effects of stem cells of dental origin (DSCs) on blood glucose or DPN parameters, when administered in diabetic animals. The search was conducted in multiple stages. In the first step, a search was performed using the Cochrane Library (Issue 12, 2015), PubMed (MEDLINE—1996), Scopus (1990), Ovid (Embase-1974), and Web of Science (1996) electronic databases. A search was also carried out for grey literature in OpenGrey (openSIGLE 2007). There were no restrictions regarding publication date, and the last search was performed in July 2023. The titles and abstracts were read to determine if they potentially fit the inclusion criteria. Duplicate articles were removed. If the full text was not available from the databases for review or additional information was deemed necessary for selection, the corresponding authors of potential studies were contacted via email. Following this, the full text of potential studies was read to evaluate if they should be included in the review. In the next stage, during July 2023, reference lists of all articles included in the initial step were manually searched. There were no language restrictions in our search strategy.

The search was conducted using MeSH (medical subject heading) terms belonging to the categories of disease, intervention, and population in different permutations and combinations-“Diabetes” [MeSH] OR “Diabetes Mellitus” [MeSH] OR “glucose” [MeSH] OR “insulin” [MeSH]) AND “dental stem cells” [MeSH] OR “Periodontal stem cells” [MeSH] OR “gingival stem cells” [MeSH] OR “glycemic control” [MeSH]. Free text was also used, which included “diabetes”, “diabetes mellitus”, “diabetes mellitus type 1”, “diabetes mellitus type 2”, “glucose”, “insulin”, and “dental stem cells”, “periodontal stem cells”, “gingival stem cells”, and “glycemic control”. In addition, search filters, as described by Hooijmans et al. (2010) [23], were employed for a more comprehensive retrieval of animal studies from the databases. The full version of the search filters used is presented in Supplementary Table S3.

2.2. Selection Process

The titles and abstracts of all records were screened by all authors (P.T., V.T., S.J., and G.Y.) independently. In all cases, disagreements among the reviewers regarding which articles to read through full text were resolved through discussions. All authors then read through full text articles to determine inclusion. The reference lists of selected articles were read by the authors independently. The final selection of studies was discussed, and in case of disagreements regarding inclusion of articles, a consensus was reached among the authors. Automation tools were not used at any stage of the defined search protocol.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Animal studies, regardless of species, age, and gender, published in or before July 2023, were included.

- Studies in which the disease model was induced diabetes mellitus (Type 1 or Type 2), with any manner of disease induction, were included.

- Studies which included control groups with animals administered with saline or vehicle for comparison were included in the review.

- Studies which used dental stem cells, i.e., stem cells of dental origin, as the intervention were included, regardless of dose, timing, frequency, preparation, and route of administration. There were no restrictions regarding the source or portion of the tooth or its supporting tissues from which the DSCs were isolated.

- Studies using blood glucose and/or verifiable parameters of diabetic polyneuropathy, such as sensory and motor nerve conduction velocity (SNCV and MNCV), as outcome variables were included.

- Grey literature, such as preprints, dissertations, theses, unpublished manuscripts, and conference papers was also reviewed to determine if it met the inclusion criteria mentioned above.

There were no restrictions in regards to the language of the articles.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

- Animal studies which did not include diabetic models were not included in the review. In addition, animal studies which did not include diabetic controls administered with saline or vehicle for comparison with diabetic animals administered with DSCs were excluded.

- Studies in which diabetes mellitus was induced after DSC administration were excluded.

- Studies which did not use stem cells of dental origin were not included in the review.

- Studies which did not measure blood glucose and/or DPN parameters, or in which these variables were not measured using valid methods, were not included in the review.

- In vitro studies, surveys, and questionnaires were not included.

- Reviews and duplicate articles were excluded.

The complete list of studies that were excluded after reading the full text is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

2.5. Data Extraction

The data extracted from selected studies regarding the study design included country of origin, method of conducting the experiment, and study duration. Data regarding the animal model included species, age of animals at the start of the experiment, method of diabetes induction, and time of sacrifice. Information regarding the type of DSCs used in the study, source, preparation, dose, and route of administration was extracted. Changes in primary outcome variables, i.e., fasting and/or random blood glucose, and DPN parameter values, such as SNCV and MNCV, from baseline to the end of the experiment following DSC administration, were included. Other outcome measures were also noted, if present.

All authors were involved in data extraction. In case of unreported or missing data, the authors of the selected studies were contacted via email. WebPlotDigitizer, a web-based tool (https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer (accessed on 3 August 2023)) was used if data was presented graphically.

2.6. Assessment of Internal Bias in Articles

The internal bias in each study was assessed using the SYRCLE (Systematic Review Center for Laboratory Animal Experimentation) tool by Hooijmans et al. (2014) [24], which in turn is based on Cochrane’s RoB (risk of bias) tool [25]. The assessment of internal bias was conducted by each of the authors (P.T., V.T., S.J., and G.Y.) individually.

2.7. Assessment of External Validity

The external validity of the studies was analyzed using a table that examined data from included studies to determine the scope of translation of DSC therapy to humans.

2.8. Meta-Analysis

Review Manager (RevMan), version 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) [26], and MAJOR with jamovi statistical software (version 2.3) [27] were used to perform quantitative analyses when more than two studies provided data for each outcome of interest.

Due to anticipated differences in design and effect sizes between studies, random effects model was used for calculating summary effect estimates [28]. The inverse variance method was used to combine results across studies because with this method, more weight is assigned to studies with smaller standard errors; hence, there is greater precision in the overall summary effect [28]. Standardized mean difference (SMD) was used as the outcome measure due to inter study differences in units and methods for measuring outcomes [29]. Hedges’ adjusted g method [30] was used to compute SMD, as it adjusts for small sample bias. The SMD was presented with 95% confidence interval (CI), which represented the range in which one can be 95% certain that the true value of the SMD lies [31]. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the pooled summary effects.

DerSimonian–Laird estimator was used to calculate the extent of heterogeneity (i.e., tau2) among the studies [32]. Knapp–Hartung method [33] was used to reduce the risk of Type 1 error (i.e., incorrect rejection of a null hypothesis that is actually true), particularly in analyses that constituted a small number of studies. In addition, Cochran’s Q-test and its p value were calculated to determine potential heterogeneity [34]. A p-value of less than 0.05 was indicative of presence of heterogeneity, which cannot be attributed only to chance [28]. I2 statistic was used to examine the degree of heterogeneity [28]. I2 values of 50% or more were deemed as indicative of substantial heterogeneity [28]. Further, the prediction interval, which helps demonstrate the range of true effects that may be expected in future similar studies [35,36], was also calculated for each outcome.

Studentized residuals were calculated to identify potential outliers, i.e., studies with 95% confidence intervals that were outside those of the pooled effect [37]. The equation 100 × (1 − 0.05/(2 × k)) th percentile of a standard normal distribution, i.e., Bonferroni correction [38] with 2 sided alpha = 0.05 for k number of studies, was calculated for each analysis, and if the studentized residual range of a study exceeded this value, it was considered an outlier in the model. Studies that may have excessively leveraged the pooled effect were identified using Cook’s distances [39]. If the Cook’s distance of a study was larger than the median plus six times the interquartile range of the Cook’s distance, it was considered to be influential in the context of the analysis [39].

Multiple reports of the same study describing different outcome measures were identified during data collection. In such cases, data from all reports was collected and presented as a single study in the systematic review, and relevant quantitative data from only one report per study was used in each meta analysis to avoid unit of analysis errors [40]. For multiple-arm studies, all relevant intervention groups were combined to create one group for a single paired comparison with the control group to avoid ‘double -counting’ of animals [41]. For studies with a cross-over design, each paired analysis was estimated by calculating mean difference and standard error of the mean difference and entering the data in the analysis in the form of generic inverse variance outcome [41].

2.8.1. Subgroup Analysis

Studies included in the meta-analysis for DSC effect on blood glucose were split into subgroups to examine potential sources of heterogeneity among studies [42] and to measure various treatment effect estimates. Species differences and DSC type were used as variables to check for possible interactions among subgroups, since it was anticipated that these aspects may be potential sources of heterogeneity.

A test for significance which determines heterogeneity across subgroups was conducted, as described by Borenstein et al. (2009) [43]. The I2 statistic was used to calculate heterogeneity as a percentage in the subgroup analysis.

2.8.2. Publication Bias

If 10 or more studies provided data in the meta-analysis, the studies were assessed by funnel plot inspection for potential publication bias. Using standard error of the observed outcomes, Egger’s regression [44] and Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation [45] tests were performed to provide quantitative assessments of funnel plot asymmetry.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

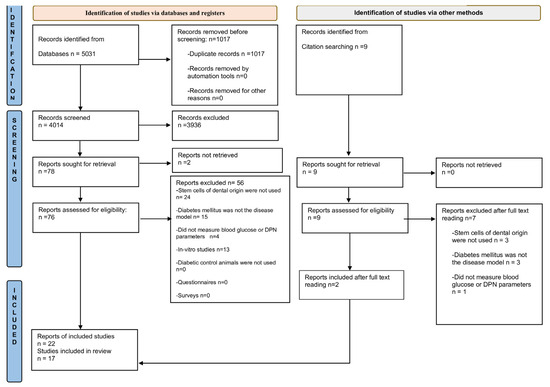

In total, the database search yielded 5031 records (Figure 1). After removing duplicate records, the abstracts of 4014 articles were screened for potential eligibility, and 76 studies were selected for full text reading. Two articles were retrieved from the reference lists of included studies. In all, 17 animal studies were included in the review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies. Flow diagram template from: Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 9 July 2023) [22].

Following a broad search using MeSH terms and free text, as described previously, and when Hooijimans’ search filters for animal studies [23] were not used, a single clinical study [6] in which DSCs were used to treat diabetic patients was retrieved. This is included in the review for the purpose of comparative analysis to determine the scope of clinical translation to humans.

3.2. Characteristics of Animal Studies

The descriptive analysis of included animal studies is presented in Table 1. Seven studies were conducted in Japan [13,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]; four in China [9,14,55,56,57]; three in Egypt [58,59,60,61]; two in India [17,62]; and one in Brazil [63].

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of animal studies.

3.2.1. Animal Model Characteristics

Streptozotocin (STZ) was used to induce T1DM in 14 studies [9,13,17,46,48,50,51,52,54,58,60,61,62,63]; T2DM was induced using a high-fat diet in 2 studies [14,55], while in 1 study, T2DM was induced in rats which were given a high-fat diet and then administered with STZ [57]. Spraque Dawley (SD) rats were used in six studies [13,46,52,57,58,61]; Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats were used in two [14,55]; Wistar rats in two [17,60]; Fischer 344 rats (F344-NJcl-rnu/rnu) in one study [54]; four studies used C57BL/6 mice [9,50,51,63]; and two used Bagg Albino (BALB/c) mice [48,62]. In 1 study, female mice were used [63], whereas 16 studies used male rats or mice. Animals were sacrificed at a timepoint ranging from 20 days to 16 weeks after the transplantation of DSCs, and 4 to 52 weeks from the induction of diabetes.

3.2.2. Dental Stem Cell Selection in Animal Studies

SHED were used in 6 studies [14,50,51,55,57,62], and human DPSCs (hDPSCs) were used in five [17,48,54,58,60]. In one study, MSCs from human gingiva (hGMSCs) were used [9], whereas in another, insulin-producing cells (IPCs) derived from human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) and hDPSCs were used [61]. Rat derived DPSCs (rDPSCs) were used in three studies [13,46,52]; one study used DPSCs derived from the incisors of mice (mDPSCs) [63]. Rodent derived DPSCs were from the same species as the animals used to study DSC effects, although autotransplantation was not performed in any study. Whole SCs were used in 14 studies [9,13,14,17,46,48,54,55,57,58,60,61,62,63], and 3 used serum-free conditioned medium containing secretory factors of SHED (SHED-CM) [50,51] or DPSCs (DPSC-CM) [52].

Intravenous (IV) route was used to administer DSCs in seven studies [14,55,57,58,60,61,63], and intramuscular (IM) route was used in five [13,46,48,50,52]. In one study, IPCs obtained from SHED were transplanted subcutaneously [62], while in another [54], IPCs were placed under renal capsules of diabetic animals. Intraperitoneal route was used in one study [9], and in another, IV route was followed by use of intraperitoneal route [51]. In two studies, IV route was compared with other methods of DSC administration such as IM [17] and intrapancreatic routes [59]. One study reported the use of tacrolimus as an immunosuppressant [54]. There were no incidents of graft rejection reported in any study.

3.3. Effect of DSCs in Animals

Following the induction of diabetes, blood glucose increased in T1DM and T2DM animals. A decline in blood [9,17,51,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] and urinary glucose [62,63] occurred after DSC administration. Serum insulin and C-peptide levels improved [59,61]. Insulin resistance decreased in one T2DM study [57], whereas in another, it increased [56]. Body weight, which had markedly reduced with STZ administration, increased following DSC administration [17,57,62,63].

DPN parameters such as SNCV, MNCV, and sciatic nerve blood flow (SNBF) improved after DSC administration [13,46,48,52]. Intra-epidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD) increased [13,14,46,52], and current perception threshold (CPT) values improved [13,48]. Hyperalgesia, measured by paw withdrawal mechanical threshold (PWMT), Von Frey hairs on hind paw test (VFH) [14] and tail flick test [63] reduced with DSC administration. Twelve weeks after T1DM induction, hypoalgesia, observed in small nerve fibers, was ameliorated following hDPSC transplantation [49]. Thus, early onset hyperalgesia and late onset hypoalgesia were reversed [14,49,63]. Thermal sensitivity, evaluated using the tail immersion test, as well as grip strength improved after hDPSCs administration [17]. In one study, rats which had been induced with T1DM 48 weeks prior to rDPSC administration, showed improvement in DPN parameters [13].

A restoration of islet structure was observed [9,57,59,61,62,63]. Insulitis in T1DM animals reduced after administration of hGMSCs [9]. DSCs engrafted and transdifferentiated into insulin secreting cells in the pancreas following various routes of administration [9,51,56,63]. Ki67, a biomarker for cell differentiation, revealed an increase in the proliferation of islet cells [57,59]. The ratio of insulin secreting β cells to total pancreatic cell mass increased [9,59]. hDPSC transplantation resulted in the downregulation of caspase-3, a protease which mediates cell apoptosis, and there was an increase in beta cell mass [58].

In T2DM rats, glycogenesis and glycogen storage increased, and glycolysis reduced following SHED administration [56]. T2DM induced renal tubular dilatation and glomerulosclerosis [55], and T1DM-induced loss of the renal tubular epithelial brush border was reversed [63] following IV administration of DSCs. Inada et al. (2022) reported the presence of engrafted IPCs in the kidneys, 4 weeks after transplantation underneath the renal capsule; however, kidney function was not affected [54]. hDPSCs homed into STZ-induced injured parotid gland tissue after administration via the tail vein [58]. Parotid gland weight and salivary flow increased [58].

DPSCs differentiated into vascular endothelial cells [46]. The capillary-muscle ratio improved in muscles in which DSCs had been administered [13,14,46,49,50,52]. Myelin thickness and area increased [13], and the axonal circularity of sural nerves [47] improved. Intriguingly, hGMSCs engrafted mainly in the mesenteric and pancreatic lymph nodes, and to a lesser extent, in the pancreas, 4 weeks following intraperitoneal administration [9].

A reduction in C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-α, IL1, IL6, IL17, and interferon-γ was observed after DSC administration [9,17,47,55,57]. Arachidonic acid [17], transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [17], and IL10 [47,55] increased. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [47,49,58], nerve growth factor (NGF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) levels improved [13,49,53].

Compared to IV, repeat IM doses were more effective in improving DPN measures in one study [17]. The effects on blood glucose were similar in intrapancreatic and IV administrations of hDPSCs in another study [59]. Improvements in DPN parameters were comparable with DPSCs and SFs of DPSCs [53]. More effective glycemic control was observed with human DSCs than with human BMMSC treatment [51,54].

3.4. Characteristics of the Clinical Study and Effects of DSCs in Humans

The clinical study was a proof of concept study conducted in China. SHED, which had been isolated from exfoliated teeth of donors, were used in T2DM patients [6]. A total of 24 patients, 45–65 years of age, were enrolled [6]. Daily insulin requirements reduced during the 6-week treatment period and the 12 months of follow up. Fasting blood glucose levels were significantly lower than those at baseline during treatment, but not at the end of follow up [6]. Post-prandial serum C-peptide significantly increased after the treatment period compared to baseline, but the increase was not statistically significant at the end of follow up.

3.5. Internal Validity of Animal Studies

The SYRCLE tool, by Hooijmans et al. (2014) [24], consists of six categories: selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting biases. The sixth category includes other potential sources of bias, such as pooling of drugs and unit of analysis errors. In general, details regarding study design, such as randomization during allocation, were not mentioned or were unclear (Table 2). Further, the health status of the teeth used to harvest DSCs should be reported, as carious pulpal involvement and history of invasive procedures may affect DSC viability [20,64].

Table 2.

Internal validity in animal studies. The table is based on the SYRCLE (Systematic Review Center for Laboratory Animal Experimentation) tool by Hooijmans et al. (2014) [24], which in turn is based on the Cochrane RoB (Risk of bias) tool [25], to assess the risk of internal bias. The tool includes six main categories of bias including selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other sources of bias, such as unit of analysis errors and pooling drugs or contamination. Each category consists of components or ‘domains’ (ten in all). Hooijmans et al. formulated a series of questions under each domain that helps reviewers to ascertain the risk of bias in the studies. If a signaling question is answered with a ’no’, it is indicative of high risk of bias; if it is answered with a ’yes’, it indicates a low risk of bias, and an answer of ’unclear’ indicates an unclear risk of bias in that domain. In this table, ‘Low’ means that that all the signaling questions in that domain were answered with a ‘yes’ and hence, the risk in that domain is deemed low by the reviewers. ‘High’ means that at least one signaling question related to the domain was answered with a ’no’ and is hence deemed to have a high risk of bias in that domain and category. ‘U’ signifies that the risk of bias in that category is unclear, because some or all answers to the signaling questions in that domain are unclear.

In some studies [14,48,51,53,56,57,58], the author(s) who designed the protocol also conducted the experiments and interpreted the results. According to Hooijmans et al. [24], this may create a risk for performance bias, due to inadequate blinding of investigators from knowing which intervention was provided to each animal. Some studies assessing the effects of DSCs on blood glucose in T1DM as an outcome measure [54,58,60,61] did not report changes in body weight during and after treatment. It is imperative that body weight is measured, particularly in T1DM animal models, to ensure that glucose does not decrease because of toxic effects of the intervention or loss of appetite from stress [12]. In some studies, the hind limb on one side was used for administration of DSCs, and the contralateral hind limb of the same animal was used as a control [13,47,48]. This could have led to unit of analysis errors, as potential systemic effects were not considered, and it was uncertain whether or not DSCs affected the side of the animal in which their effects were not intended.

Insulin was administered through the course of the experiments in two studies to prevent excessive hyperglycemia and simulate long-term diabetes mellitus occurring in humans [13,17]. This could have confounded the true effects of DSCs on blood glucose. For instance, in another study [54], insulin implants were placed in animals and were removed 2 weeks before the end of the experiment. While on extrinsic insulin, blood glucose levels decreased in all SC treated diabetic groups and were comparable to those in the normal control group [54]. However, after insulin implant removal, blood glucose increased in all SC treated diabetic groups, except in the hDPSC group which had undergone a 3D differentiation protocol prior to administration [54].

3.6. External Validity of Animal Studies

The extent to which data from animal studies can be reliably applied in humans was analyzed (available as Supplementary Table S4).

It is important that studies represent heterogeneity in human populations [65,66]. Rodents of identical strain, species, age, and gender were used in the animal studies. In the clinical study [6], the exclusion criteria precluded the inclusion of patients that diabetes often manifests in, such as pregnant women and patients with co-morbidities [11,12].

The use of an appropriate study population better reflects the disease in humans [65,66]. The age of animals used in T1DM studies ranged from 5 to 16 weeks at the time of disease induction; the age of animals used in T2DM studies ranged from 10–12 weeks. In addition, only one animal study [63] used female rodents. On the other hand, it was unclear how many females and males were enrolled in the clinical study [6].

Omi et al. (2017) established a diabetic rodent model 48 weeks prior to rDPSC administration [13]. Since the lifespan of SD rats ranges between 2.5 and 3.5 years [67,68], this study can be considered to be a long-term diabetic rodent model. The clinical study [6] population was an appropriate representation of a chronic form of diabetes, as the patients had been diagnosed with T2DM for more than 5 years and were using insulin for not less than one year.

It is imperative that DSC therapy is not toxic and is, at the same time, effective for glycemic control and DPN. The definitions for diabetes are different for mice, since they tend to have higher blood glucose concentrations than humans [69]. Furthermore, organs such as the pancreas, liver, kidneys, brain and muscles were removed for histological study after sacrifice in the animal studies. In contrast, postmortem tests are not routinely performed in humans to verify the results of treatment [24].

3.7. Meta-Analysis

3.7.1. Forest Plot Analysis

Effect of DSCs on Blood Glucose

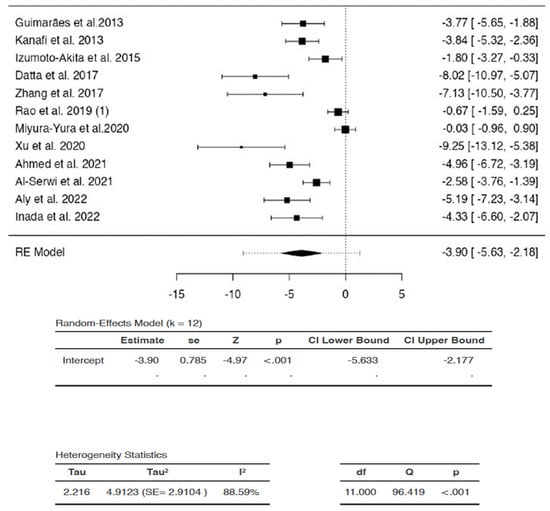

The SMDs of individual studies were within the range of -9.2479 to −0.0270 (Figure 2). The average SMD of the analysis was observed to be −3.905 (95% CI: −5.6330 to −2.177). The average outcome differed significantly from zero (Z = −4.9737, p = 0.0004). Hence, the analysis indicated that there was a significant reduction in blood glucose in favor of DSC administration compared to saline/vehicle.

Figure 2.

Effects of dental stem cells on blood glucose. (RE—random-effects, k—number of studies in analysis, SE—standard error, Z—test for overall effect, p—level of statistical significance, CI—confidence interval, Tau2—absolute value of variance i.e., heterogeneity among effect sizes, I2—statistic for degree of heterogeneity, df—degrees of freedom, Q—Cochran’s Q-test value).

There was substantial heterogeneity between studies (Q = 96.4187, p < 0.0001, tau2 = 4.9123, I2 = 88.5914%). A 95% prediction interval for true effects was estimated to be −9.0802 to 1.2702. Hence, the 95% range of true effects contained values that were less than zero, as well as values that were more than or equal to zero. This means that even though the average outcome (Z = −4.9737) and summary point estimate (SMD = −3.905) were negative, indicating a reduction in blood glucose, DSCs may in fact, have no effect or may even increase blood glucose in similar settings, with the greatest increase in blood glucose represented as SMD of 1.2702 in the analysis.

The studentized residuals showed that none of the studies could be considered to be outliers in the context of the analysis. In addition, none of the studies were overly influential according to Cook’s distances (data for studentized residuals and Cook’s distance analyses are available as supplementary data).

Effects of DSCs on SNCV

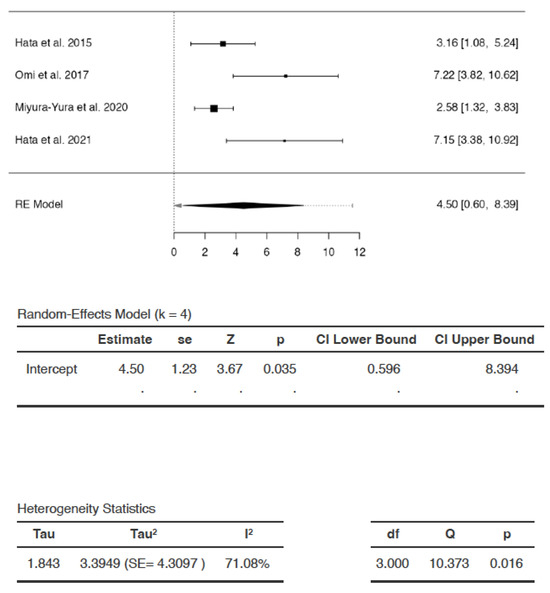

The SMDs ranged from 2.5757 to 7.2217 (Figure 3). The estimated average SMD was 4.4952 (95% CI: 0.5959 to 8.3945). The average outcome differed significantly from zero (Z = 3.6688, p = 0.0350). Hence, following DSC administration, there was a statistically significant increase in SNCV compared to saline/vehicle.

Figure 3.

Effect of dental stem cells on sensory nerve conduction velocity (SNCV). (RE—random-effects, k—number of studies in analysis, SE—standard error, Z—test for overall effect, p—level of statistical significance, CI—confidence interval, Tau2—absolute value of variance i.e., heterogeneity among effect sizes, I2—statistic for degree of heterogeneity, df—degrees of freedom, Q—Cochran’s Q-test value).

The analysis revealed significant heterogeneity (Q = 10.3734, p = 0.0156, tau2 = 3.3949, I2 = 71.0799%). A 95% prediction interval for true effects was estimated to be −2.5467 to 11.5371. Hence, although the average outcome (Z = 3.6688) and summary point estimate (SMD = 4.4942) were positive, indicating an increase in SNCV after DSC administration, the SNCV may remain unchanged or may even decrease following DSC administration in a future study in a similar setting, with the greatest reduction in SNCV represented as SMD of −2.5467. The studentized residuals revealed that there were no outliers in the context of this model. According to Cook’s distances, none of the studies could be considered to be overly influential.

Effects of DSCs on MNCV

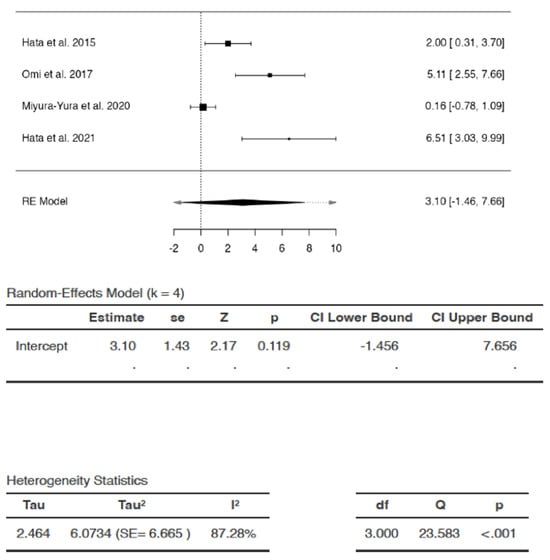

The SMDs of studies ranged from 0.1556 to 6.5147 (Figure 4). The average SMD was 3.1001 (95% CI: −1.4558 to 7.6559). The average outcome did not differ significantly from zero (Z = 2.1655, p = 0.119). Hence, the increase in MNCV after DSC treatment compared to that following saline/vehicle administration was not significant.

Figure 4.

Effects of dental stem cells on motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV). (RE—random-effects, k—number of studies in analysis, SE—standard error, Z—test for overall effect, p—level of statistical significance, CI—confidence interval, Tau2—absolute value of variance i.e., heterogeneity among effect sizes, I2—statistic for degree of heterogeneity, df—degrees of freedom, Q—Cochran’s Q-test value).

There appeared to be substantial heterogeneity (Q = 23.5832, p < 0.0001 tau2 = 6.0734, I2 = 87.2791%). A 95% prediction interval for true effects was estimated to be −5.9701 to 12.1702. Hence, although the average outcome (Z = 2.1655) and summary point estimate (SMD = 3.1001) were positive, indicating improvement in MNCV after DSC administration, the MNCV might remain unchanged or may even reduce following DSC administration in similar settings. In some cases, the result of DSC treatment may even be the exact opposite of the summary point estimate SMD, i.e., −3.1001 instead of 3.1001, with the greatest reduction in MNCV represented as SMD of −5.9701 in the analysis. The studentized residuals revealed that none of the studies could be considered as outliers in the analysis. According to Cook’s distances, none of the studies were overly influential.

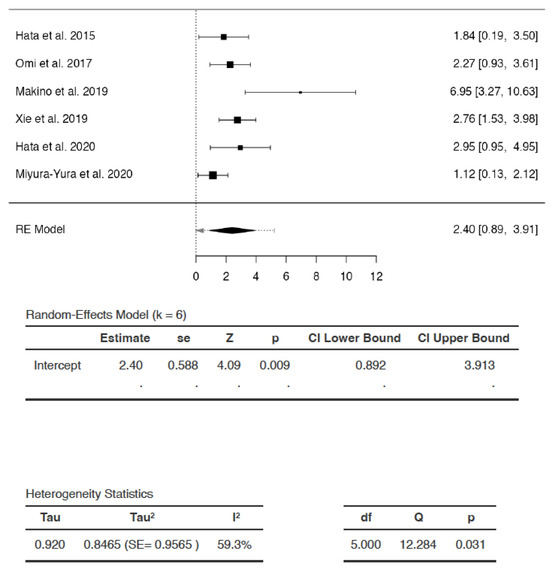

Effects of DSCs on Capillary–Muscle Ratio

The SMDs of the studies ranged from 1.1249 to 6.9490 (Figure 5). The estimated average SMD was 2.4027 (95% CI: 0.8923 to 3.9132). The average outcome was significantly different from zero (Z = 4.0891, p = 0.0095) (Figure 4). Hence, the analysis indicated that the capillary–muscle ratio increased significantly in favor of DSC treatment compared to saline/vehicle administration.

Figure 5.

Effects of dental stem cells on capillary–muscle ratio (RE—random-effects, k—number of studies in analysis, SE—standard error, Z—test for overall effect, p—level of statistical significance, CI—confidence interval, Tau2—absolute value of variance i.e., heterogeneity among effect sizes, I2—statistic for degree of heterogeneity, df—degrees of freedom, Q—Cochran’s Q-test value).

There appeared to be heterogeneity among studies (Q = 12.2844, p = 0.0311, tau2 = 0.8465, I2 = 59.2979%). A 95% prediction interval for true effects was −0.4035 to 5.209. Hence, although the average outcome (Z = 4.0891) and summary point estimate (SMD = 2.4027) were positive, indicating that capillary-muscle ratio improved with DSC administration, it may in fact remain unchanged or even reduce following DSC administration in similar settings, with the greatest reduction in capillary–muscle ratio represented as SMD of −0.4035.The studentized residuals revealed that none of the studies could be considered as outliers in the context of the analysis. According to Cook’s distances, none of the studies were overly influential.

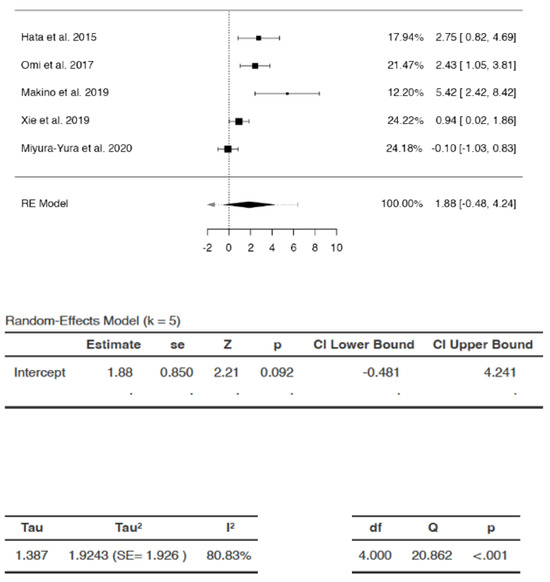

Effects of DSCs on IENFD

The SMDs ranged from −0.0994 to 5.4206 (Figure 6). The average SMD was calculated to be 1.8802 (95% CI: −0.4809 to 4.2413). The average outcome did not differ significantly from zero (Z = 2.211, p = 0.0915). Hence, the increase in IENFD was not statistically significant following DSC administration compared to saline/vehicle.

Figure 6.

Effects of dental stem cells on intra-epidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD). (RE—random-effects, k—number of studies in analysis, SE—standard error, Z—test for overall effect, p—level of statistical significance, CI—confidence interval, Tau2—absolute value of variance i.e., heterogeneity among effect sizes, I2—statistic for degree of heterogeneity, df—degrees of freedom, Q—Cochran’s Q-test value).

There appeared to be substantial heterogeneity (Q = 20.8617, p = 0.0003, tau2 = 1.9243, I2 = 80.8261%). A 95% prediction interval for true effects was estimated to be −2.6374 to 6.3978. Hence although the average outcome (Z = 2.211) and summary point estimate (SMD = 1.8802) were positive, indicating an increase in IENFD after DSC administration, it may remain unchanged, or may even reduce following DSC administration in similar settings. In some cases, DSC treatment may even result in the exact opposite of the summary estimate, i.e., −1.8802 instead of 1.8802, with the greatest possible reduction in IENFD represented as −2.6374 in the analysis. The studentized residuals revealed that none of the studies could be considered outliers in the context of this model. According to Cook’s distances, none of the studies were overly influential in the analysis.

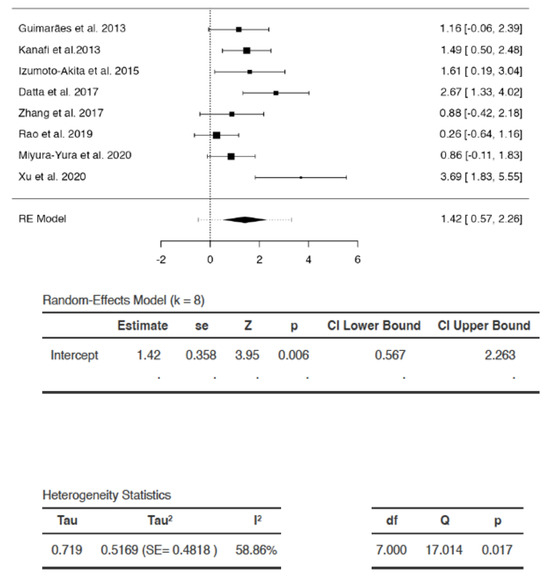

Effect of DSCs on Body Weight

The SMDs of the individual studies ranged from 0.2578 to 3.691 (Figure 7). The estimated average SMD was 1.415 (95% CI: 0.5674 to 2.2627). The average outcome differed significantly from zero (Z = 3.9475, p = 0.0056). Hence, the increase in body weight with DSC administration was statistically significant compared to saline/vehicle.

Figure 7.

Effects of dental stem cells on body weight. (RE—random-effects, k—number of studies in analysis, SE—standard error, Z—test for overall effect, p—level of statistical significance, CI—confidence interval, Tau2—absolute value of variance i.e., heterogeneity among effect sizes, I2—statistic for degree of heterogeneity, df—degrees of freedom, Q—Cochran’s Q-test value).

There appeared to be heterogeneity (Q = 17.0143, p = 0.0173, tau2 = 0.5169, I2 = 58.8583%). A 95% prediction interval for true effects was estimated to be −0.4846 to 3.3146. Hence, although the average outcome (Z = 3.9475) and summary point estimate (SMD = 1.415) were positive, indicating that the body weight of the diabetic animals increased with DSC administration, it may not be affected, or may even decrease with DSC administration in some studies in similar settings, with the greatest decrease in body weight observed to be SMD of −0.4846. None of the studies could be considered to be outliers or to be overly influential, according to studentized residuals and Cook’s distances.

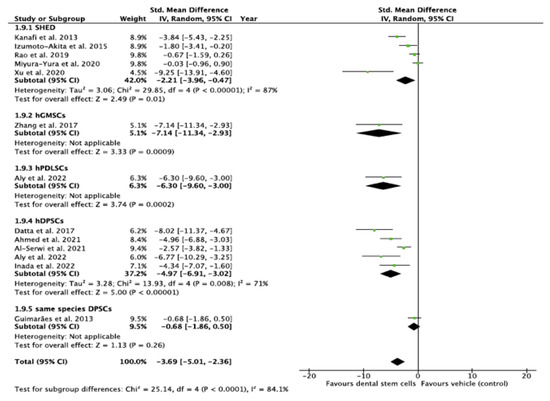

3.7.2. Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup Analysis of the Effect of DSC Type Used in the Study

The test indicated that there is a statistically significant subgroup effect (p < 0.0001), suggesting that DSC type may alter its effects on blood glucose (Figure 8). In all subgroups, DSCs were more beneficial in lowering blood glucose than saline/vehicle. Since the effect was seen more in some groups than in others, the subgroup effect was deemed quantitative. However, fewer studies were present in the hGMSCs, hPDLSC, and same species DPSC subgroups (Figure 8). In addition, there was substantial heterogeneity within the SHED (I2 = 87%) and hDPSC (I2 = 71%) subgroups. Due to the disparate number of studies and heterogeneity within the subgroups, the results of the analysis may not be reliable for interpretation.

Figure 8.

Subgroup analysis with dental stem cell type as the variable. (Tau2—value of variance among effect sizes, Chi2—value of chi-squared test for heterogeneity, df—degrees of freedom, I2—degree of heterogeneity, Z—test for overall effect, p—level of statistical significance).

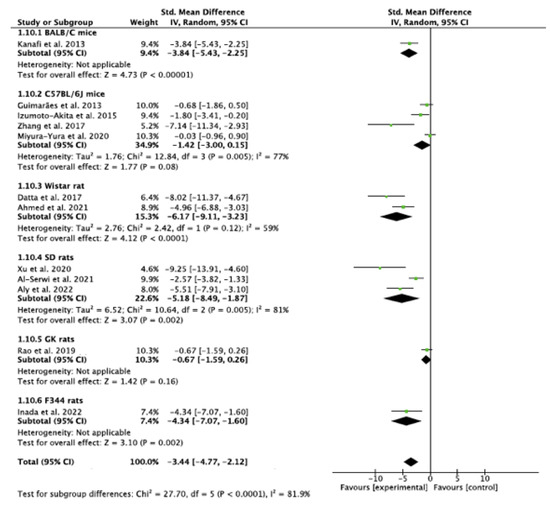

Subgroup Analysis of the Effect of Species Variations

The analysis indicated that there is a statistically significant subgroup effect (p < 0.0001), suggesting that differences in species may influence the effect of DSCs on blood glucose (Figure 9). In all subgroups i.e., among all strains of rodents used, DSCs were more beneficial in lowering blood glucose than saline/vehicle. Since the effect was seen more in some groups than in others, the subgroup effect is quantitative. However, there was disparity in the number of studies in subgroups. In addition, there was substantial heterogeneity within the C57BL/6 (I2 = 77%), SD (I2 = 81%), and Wistar rat (I2 = 59%) subgroups. Hence, the findings may not be considered reliable.

Figure 9.

Subgroup analysis with species as the variable. (Tau2—value of variance among effect sizes, Chi2—value of chi-squared test for heterogeneity, df—degrees of freedom, I2—degree of heterogeneity, Z—test for overall effect, p—level of statistical significance).

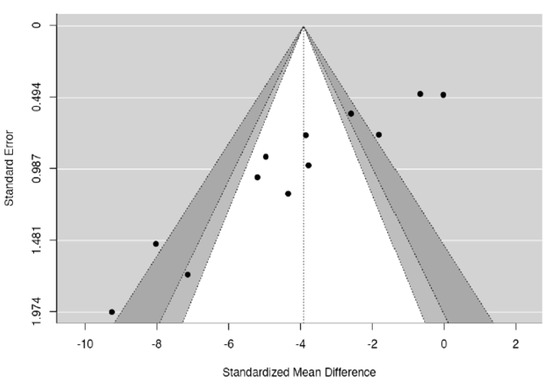

3.7.3. Funnel Plot Analysis and Publication Bias

Upon visual assessment, the funnel plot for DSC effects on blood glucose appeared asymmetrical around the vertical line representing the summary effect (Figure 10). Both regression and rank correlation tests indicated the presence of funnel plot asymmetry (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0018, respectively) (Table 3). The asymmetry could be present due to publication bias, heterogeneity among the studies, methodological design of the studies, or chance [28,40].

Figure 10.

Funnel plot.

Table 3.

Egger’s regression and Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation tests for funnel plot.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta analysis that explicates the scope of various dental stem cells in the management of hyperglycemia and DPN. Quantitative analysis in the present review indicated that there was a significant reduction in blood glucose (p = 0.0004) in diabetes-induced animals following DSC administration.

The underlying mechanisms of DSCs have not been fully established. Following administration, they induce differentiation of pancreatic progenitor cells [59], promote transdifferentiation of α into β cells [57], and modulate β cell function [55,57]. Emerging evidence indicates that extracellular apoptotic vesicles (apoVs) containing proteomes are pivotal in mediating MSC functions [70]. DSCs act by paracrine signaling, secreting VEGF and bFGF, which are important for tissue growth and regeneration [13,46,53]. They also release neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) and NGF, which are essential in neuronal development and repair [13,49,50,53].

The pooled effects showed that SNCV (p = 0.035) and capillary–muscle ratio (p = 0.0095) improved significantly following DSC administration, but IENFD (p = 0.0915) and MNCV (p = 0.119) did not. IEFND is used to measure neuropathy of small fibers, such as unmyelinated C and Aδ fibers. The findings are consistent with a study in which, 16 weeks after T1DM was induced and 4 weeks after SHED-CM was administered, there was neither any improvement in IEFND, nor in thermal and tactile sensitivity tests, indicating that DSCs were unable to reverse advanced stages of hypoalgesia in DM [50]. In addition, due to the larger diameter of motor nerves, changes in MNCV occur later than those in SNCV [50]. In the same study, 4 weeks after SHED-CM was administered, MNCV did not improve, suggesting that the duration of the experiment may have been insufficient to detect changes in MNCV [50]. Hence, the review reflects that studies with longer follow-up periods, using long-term diabetes-induced animals, may be most appropriate to demonstrate the effects of DSCs on IENFD and MNCV in advanced stages of DPN.

Human derived DPSCs were able to transdifferentiate into insulin-producing β cells in the murine pancreas following IV and intrapancreatic administration [59]. Interestingly, the new cells were morphologically identical to those of the recipient animals, and the levels of human, as well as murine insulin increased in these animals [59].

A reduction in TNF-α and an increase in IL10 [47] was observed in the DSC-administered muscle on one side, compared to the contralateral side of the same animal. This is connotative of the local effects of DSCs. On the other hand, IV administration also resulted in significant improvement in hyperalgesia and late onset hypoalgesia, indicating a systemic effect by reducing blood glucose [63]. DSC engraftment in injured organs and the subsequent amelioration of DPN [63], liver disease [56], and impaired salivary flow [58] following IV administration may be suggestive of both local and systemic effects.

The IV route of DSC administration is congruent with MSC-based therapy for controlling hyperglycemia and systemic inflammation [14]. On the other hand, a single IM dose of hDPSCs resulted in improvement in DPN parameters which lasted for 16 weeks in T1DM induced rats [48]. Irrespective of the route, repeat doses may be more effective in long-term diabetes due to sustained effects on cytokines [17,55,63]. Li et al. (2021) reported that the effective rate of three IV doses of SHED, at the end of a 12 month follow up for diabetic patients was 68.18%, suggesting that therapy may be effective for at least one year [6].

The viability of SCs is affected by aging and disease; hence, it is important to isolate them from healthy teeth at a young age [13,46,48]. Cryopreservation may hold the key to effective autologous DSC therapy, as they can be isolated from healthy teeth which have been extracted at a young age, thawed, and expanded in culture when needed [13,46,48]. Cryopreserved rDPSCs demonstrated proliferative capacities that were comparable to freshly isolated rDPSCs in T1DM rats, and were able to maintain their viability for at least 6 months before administration [46]. However, cryopreservation should be studied further before clinical application with DSCs due to the risk of solution effect injury, toxicity, arrhythmia, and hypotension [71].

4.1. Scope of Translation of Dental Stem Cell-Based Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus

For research to be effectively translated, studies should accurately predict the clinical course in humans. In the presence of substantial heterogeneity among studies, the prediction interval in each analysis demonstrates how different the true effect in a new study might be from those observed in previous similar studies. It thus, also provides insight into the uncertainty in predicting the effect in settings that may be different from those included in the analysis, thereby pointing to the challenges in translation to clinical settings.

It was unclear whether adequate randomization, allocation, concealment, and blinding were followed in the animal studies included in the review (Table 2). Failure to adhere to these principles may have led to overestimating the efficacy of DSCs.

In order to optimize their contribution to clinical practice, studies should reflect the disease as well as the population for which the intervention is intended. The homogeneity in animal samples may render them unrepresentative of heterogeneous human populations [65,66]. Further, the selection of healthy animals with no prior disease, as well as shorter duration of most of the studies, do not reflect the complexity of diabetes, nor recapitulate its slow and progressive nature [65,66]. The timing of the intervention should also model the delay between the onset of symptoms and treatment that often occurs in humans. Another factor is that many organ systems are still developing in the age range of the animals used in the studies, and the changes that occur in this phase could have affected the variables that were being measured [67,68]. Moreover, diabetes, particularly T2DM, typically manifests in older individuals. In addition, although sex effects are present in diabetes, it is widely prevalent in both males and in females [72], whereas only one animal study demonstrated the effects of DSCs in female mice [63]. These factors may impede clinical translation.

The most intractable aspect of animal studies undermining their external validity is the inherent interspecies differences [65,66]. Rodents are used in biomedical research due to their genetic and physiological similarities to humans [12]. Their life stages mimic those in humans [12]. However, modern rodents have adapted to their own unique environment and have evolved to respond to diseases and interventions differently than humans [65]. Moreover, genetic variations exist, even within individual strains of the same species, such as C57BL/6 mice and GK rats, which must be considered while designing a study and interpreting its results [12].

Similar to the animal studies, the follow-up phase in the clinical study was adequate to monitor immediate and early adverse effects, but may not have been sufficient to determine long-term complications. Sometimes, certain properties of a drug may go unnoticed, even after it has passed safety checks in preclinical and short-term clinical studies. An example is the antiviral drug fialuridine, which had potential use in the treatment of hepatitis B [73]. It had passed preclinical investigations, and pilot studies with 2 and 4 week courses of the drug. However, during the 13th week of a phase 2 clinical trial, following administration of doses which were several hundred times smaller than the dose deemed safe in laboratory animals, patients suffered severe hepatotoxicity, resulting in the deaths of five patients [73]. The lesson to be learned from this tragedy is that not only are species variations underestimated, but that the duration of studies is also often insufficient to assess the risk of chronic toxicity. Even if a drug is deemed safe in animals at much higher doses, it may exhibit vastly different pharmacological properties in humans.

4.2. Publication Bias

Both Egger’s regression (p < 0.0001) and Begg and Majumdar rank correlation (p = 0.0018) tests indicated funnel plot asymmetry. One of the reasons for this asymmetry may be publication bias. This means that studies which reported amelioration of hyperglycemia were more likely to be published than studies that reported no change, or reported an increase in blood glucose. Such selective publication can hinder effective translation because the interpretation and implementation of data will be based only on partial evidence [66]. It results in the wastage of animals and resources used in unpublished studies.

4.3. Graft Rejection, Tumorigenesis, and Other Adverse Reactions

MSCs are not completely immunoprivileged and sometimes undergo graft rejection [5]. Although all the studies including the clinical study [6], used allogeneic or xenogeneic sources for DSCs, only one animal study [54] described the use of tacrolimus. Most MSCs become trapped in the lungs at some point [5,6,57] or undergo apoptosis after administration [6]. However, their fate is still obscure. Engraftment occurred in organs such as the pancreas, liver, kidneys, and muscles following various routes of administration [9,14,46,48,55,58,63]; however, in one study, it was reported that after intraperitoneal administration, very few DSCs engrafted in the lungs and brain [9]. Hypoxia, hyperglycemia, and inflammation may contribute to the homing tendencies of MSCs [55]. In diabetes, there may be multiple organs with varying degrees of inflammation [74]. Hence, potential interactions in the local environment and the risk for tumorgenicity in every organ and tissue should be studied. Another factor to consider is the risk of teratoma, a phenomenon observed when embryonic stem cells are injected in mice, and a hallmark of pluripotent stem cells [75]. Although isolated DSCs are specifically induced in the laboratory to become committed to the desired cell phenotype in vivo, their broad spectrum differentiation potential must not be ignored. Common side effects of MSC therapy in DM, such as hypoglycemia, headache, fever, and rash, should also be considered [6].

Animal studies provide the foundation for testing new therapies and help to increase our understanding of an intervention. The present systematic review aimed to provide insight into the applicability of teeth and supporting tissues as potential sources of stem cells in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. The review also underscores the importance of methodological quality of animal studies to reliably inform clinical translation. In addition, the reviewers hope to contribute to implementing the 3 Rs, i.e., replacement, refinement, and reduction, by encouraging transparent reporting, responsible use of animals, and preventing replication of flawed study designs. The review has some limitations. Substantial heterogeneity was observed, which could be attributed to factors such as differences in species, the type and preparation of DSCs, the duration of the experiments, study design, and statistical differences in results between studies [28,40]. Meta-analysis was nevertheless performed to provide quantitative assessment of the effects of DSCs and to demonstrate the differences in effects among studies. Furthermore, the disparate number of studies in the subgroups reduces the reliability of the subgroup analyses. Nonetheless, the analyses were included in the review due to the putative effects of SC type and species differences on experiment outcomes [5,8,12]. Lastly, the most crucial caveat for translation to humans is that all preclinical data should be interpreted with caution due to the irrevocable issue of interspecies differences.

5. Conclusions

The prospect of rapid and enduring glycemic control is exciting, as conventional drugs do not have lasting effects [63]. Within the limitations of this review, DSCs appear to be beneficial for glycemic control; however, the potential risk of graft rejection and tumorigenesis must not be ignored. It behooves researchers performing animal studies to adopt standards similar to those used in clinical trials, while considering methodological design and reporting. Studies with longer follow-up periods and greater sample power should be undertaken to determine long-term effects and track the fate of DSCs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijtm4010005/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Abstract checklist; Table S2; PRISMA 2020 checklist; Table S3: Full version of search filters; Table S4: Comparative analysis of included studies to determine external validity; Figure S1: Outliers and residuals for the analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T.; methodology, P.T.; software, P.T. and S.J.; literature search, P.T., V.T., S.J. and G.Y.; validation, P.T., V.T. and G.Y.; data analysis, P.T., V.T., S.J. and G.Y.; investigation, P.T., V.T., S.J. and G.Y.; data curation, P.T., V.T., S.J. and G.Y.; meta-analysis: P.T. and S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; writing—review and editing, P.T., V.T., S.J. and G.Y.; visualization, P.T., V.T., S.J. and G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Smt. Leela Idgunji, without whose unwavering support, the study would not have come to fruition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Thomas, E.D.; Lochte, H.L., Jr.; Lu, W.C.; Ferrebee, J.W. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1957, 257, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henig, I.; Zuckerman, T. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation—50 years of evolution and future perspectives. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2014, 5, e0028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Petrakova, K.V.; Kurolesova, A.I.; Frolova, G.P. Heterotopic of bone marrow. Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation 1968, 6, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Orthop. Res. 1991, 9, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiwalla, M.; Hematti, P. Mesenchymal stem cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cytotherapy 2009, 11, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Jiao, X.; Song, J.; Sui, B.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, S.; Huang, Q. Therapeutic potential of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth infusion into patients with type 2 diabetes depends on basal lipid levels and Islet function. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2021, 10, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kot, M.; Baj-Krzyworzeka, M.; Szatanek, R.; Musiał-Wysocka, A.; Suda-Szczurek, M.; Majka, M. The Importance of HLA Assessment in “Off-the-Shelf” Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stem Cells Based-Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.T.-J.; Gronthos, S.; Shi, S. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: Their biology and role in regenerative medicine. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, L.; Dang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, D.; Ma, J.; Yuan, J.; et al. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate streptozoticin-induced T1DM in mice via suppression of T effector cells and up-regulating Treg subsets. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, S. A brief history of T cell help to B cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Factors and Figures. 2021. Available online: https://www.idf.org/aboutdiabetes/what-is-diabetes/facts-figures.html (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- King, A.J. The use of animal models in diabetes research. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 166, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omi, M.; Hata, M.; Nakamura, N.; Miyabe, M.; Ozawa, S.; Nukada, H.; Tsukamoto, M.; Sango, K.; Himeno, T.; Kamiya, H.; et al. Transplantation of dental pulp stem cells improves long-term diabetic polyneuropathy together with improvement of nerve morphometrical evaluation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Rao, N.; Zhai, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, L.; Wang, Y. Therapeutic effects of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth on diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, K.; Yasujima, M.; Yagihashi, S. Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic neuropathy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, C.W.; Selvin, E. Epidemiology of Peripheral Neuropathy and Lower Extremity Disease in Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2019, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, I.; Bhadri, N.; Shahani, P.; Majumdar, D.; Sowmithra, S.; Razdan, R.; Bhonde, R. Functional recovery upon human dental pulp stem cell transplantation in a diabetic neuropathy rat model. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 1208–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.J.; Imaizumi, M.; Tsuchiya, S.; Morsceck, C. Dental follicle stem cells and tissue enjineering. J. Oral Sci. 2010, 52, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, V.; Ronald, V.; Abdullah, A.; Nathan, K.G.; Aziz, Z.A.; Abdullah, M.; Musa, S.; Abu Kasim, N.; Bhonde, R. Differentiation of dental pulp stem cells into islet-like aggregates. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, C.-T.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y.-J.; Sun, G.-L. Derivation and growth characteristics of dental pulp stem cells from patients of different ages. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5127–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Mao, J.; Liu, Y. Pulp stem cells derived from human permanent and deciduous teeth: Biological characteristics and therapeutic applications. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2020, 9, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 7 June 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Tillema, A.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M. Enhancing search efficiency by means of a search filter for finding all studies on animal experimentation in PubMed. Lab. Anim. 2010, 44, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Review Manager (RevMan), Version 5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2020.

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi [Computer Program]. Version 2.3. 2021. Available online: http://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Deeks, J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; on be half of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for SystematicReviews for Interventions Version 6.4; Cochrane: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, L.V.; Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis; Hedges, L.V., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, L.V. Distrubution theory for Glass’ Estimator of effect sizes and related estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 1981, 6, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyman, J. On the problem of confidence intervals. Ann. Math. Stat. 1935, 6, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, G.; Hartung, J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat. Med. 2003, 22, 2693–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics 1954, 10, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipa, G. The inclusion of the estimated inter-study variation into forest plots for random effects meta analysis a suggestion for a graphical representation (abstract). In Proceedings of the XIV Cochrane Colloquium, Program and Abstract Book, Dublin, Ireland, 23–26 October 2006; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- IntHout, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Rovers, M.M.; Goeman, J.J. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, A.J. The Statistics of Residuals and the Detection of Outliers; U.S. Dept. of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Survey, Geodetic Research and Development Laboratory: Miami, FL, USA, 1976; 136p. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple comparisons among means. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1961, 56, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.D. Detection of Influential Observation in Linear Regression. Technometrics 1977, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Glanville, J.; Briscoe, S.; Featherstone, R.; Littlewood, A.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Paynter, R.; Rader, T.; Thomas, J.; et al. Chapter 4. Searching for and selecting studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4; Cochrane: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Eldridge, S.; Li, T. Chapter 23. Including variants on randomized trials. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4; (updated August 2023); Cochrane: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Richardson, M.; Garner, P.; Donegan, S. Interpretation of subgroup analyses in systematic reviews: A tutorial. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2019, 7, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating Characteristics of a Rank Correlation Test for Publication Bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, M.; Omi, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Tosaki, T.; Miyabe, M.; Kojima, N.; Kubo, K.; Ozawa, S.; Maeda, H.; et al. Transplantation of cultured dental pulp stem cells into the skeletal muscles ameliorated diabetic polyneuropathy: Therapeutic plausibility of freshly isolated and cryopreserved dental pulp stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omi, M.; Hata, M.; Nakamura, N.; Miyabe, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kamiya, H.; Nakamura, J.; Ozawa, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Takebe, J.; et al. Transplantation of dental pulp stem cells suppressed inflammation in sciatic nerves by promoting macrophage polarization towards anti-inflammation phenotypes and ameliorated diabetic polyneuropathy. J. Diabetes Investig. 2016, 7, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, M.; Omi, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Miyabe, M.; Ito, M.; Ohno, T.; Imanishi, Y.; Himeno, T.; Kamiya, H.; et al. Sustainable Effects of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cell Transplantation on Diabetic Polyneuropathy in Streptozotocine-Induced Type 1 Diabetes Model Mice. Cells 2021, 10, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, M.; Omi, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Miyabe, M.; Ito, M.; Makino, E.; Kanada, S.; Saiki, T.; Ohno, T.; et al. Transplantation of human dental pulp stem cells ameliorates diabetic polyneuropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nude mice: The role of angiogenic and neurotrophic factors. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura-Yura, E.; Tsunekawa, S.; Naruse, K.; Nakamura, N.; Motegi, M.; Nakai-Shimoda, H.; Asano, S.; Kato, M.; Yamada, Y.; Izumoto-Akita, T.; et al. Secreted factors from cultured dental pulp stem cells promoted neurite outgrowth of dorsal root ganglion neurons and ameliorated neural functions in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. J. Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumoto-Akita, T.; Tsunekawa, S.; Yamamoto, A.; Uenishi, E.; Ishikawa, K.; Ogata, H.; Iida, A.; Ikeniwa, M.; Hosokawa, K.; Niwa, Y.; et al. Secreted factors from dental pulp stem cells improve glucose intolerance in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice by increasing pancreatic β-cell function. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2015, 3, e000128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, E.; Nakamura, N.; Miyabe, M.; Ito, M.; Kanada, S.; Hata, M.; Saiki, T.; Sango, K.; Kamiya, H.; Nakamura, J.; et al. Conditioned media from dental pulp stem cells improved diabetic polyneuropathy through anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective and angiogenic actions: Cell-free regenerative medicine for diabetic polyneuropathy. J. Diabetes Investig. 2019, 10, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanada, S.; Makino, E.; Nakamura, N.; Miyabe, M.; Ito, M.; Hata, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Sawada, N.; Kondo, S.; Saiki, T.; et al. Direct Comparison of Therapeutic Effects on Diabetic Polyneuropathy between Transplantation of Dental Pulp Stem Cells and Administration of Dental Pulp Stem Cell-Secreted Factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inada, R.; Mendoza, H.Y.; Tanaka, T.; Horie, T.; Satomi, T. Preclinical study for the treatment of diabetes mellitus using β-like cells derived from human dental pulp stem cells. Regen. Med. 2022, 17, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Wang, X.; Xie, J.; Li, J.; Zhai, Y.; Li, X.; Fang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, L. Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth Ameliorate Diabetic Nephropathy In Vivo and In Vitro by Inhibiting Advanced Glycation End Product-Activated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 2751475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, N.; Wang, X.; Zhai, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, L. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth ameliorate type II diabetic mellitus in Goto-Kakizaki rats. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Xie, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, C.; Huang, Q. Effects and mechanism of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth combined with hyperbaric oxygen therapy in type 2 diabetic rats. Clinics 2020, 75, e1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Serwi, R.H.; El-Khersh, A.O.F.O.; El-Akabawy, G. Human dental pulp stem cells attenuate streptozotocin-induced parotid gland injury in rats. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kersh, A.O.F.O.; El-Akabawy, G.; Al-Serwi, R.H. Transplantation of human dental pulp stem cells in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Anat. Sci. Int. 2020, 95, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 60Ahmed, H.H.; Aglan, H.A.; Mahmoud, N.S.; Aly, R.M. Preconditioned human dental pulp stem cells with Cetrium and yttrium oxide nanoparticles effectively ameliorate diabetes hyperglycemia while combating hypoxia. Tissue Cell 2021, 73, 101661. [Google Scholar]

- Aly, R.M.; Aglan, H.A.; Eldeen, G.N.; Mahmoud, N.S.; Aboul-Ezz, E.H.; Ahmed, H.H. Efficient generation of functional pancreatic β cells from dental-derived stem cells via laminin-induced differentiation. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanafi, M.M.; Rajeshwari, Y.B.; Gupta, S.; Dadheech, N.; Nair, P.D.; Gupta, P.K.; Bhonde, R.R. Transplantation of islet-like cell clusters derived from human dental pulp stem cells restores normoglycemia in diabetic mice. Cytotherapy 2013, 15, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, E.T.; da Silva Cruz, G.; De Almeida, T.F.; de Freitas Souza, B.S.; Kaneto, C.M.; Vasconcelos, J.F.; Dos Santos, W.L.C.; Ribeiro-Dos-Santos, R.; Villarreal, C.F.; Soares, M.B.P. Transplantation of stem cells obtained from murine dental pulp improves pancreatic damage, renal function, and painful diabetic neuropathy in diabetic type 1 mouse model. Cell Transplant. 2013, 22, 2345–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, A.I.; Hong, H.-H.; Lin, W.-R.; Fu, J.-F.; Chang, C.-C.; Wang, I.-K.; Huang, W.-H.; Weng, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-W.; Yen, T.-H. Isolation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Human Deciduous Teeth Pulp. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2851906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pound, P.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M. Is it possible to overcome issues of external validity in preclinical animal research? Why most animal models are bound to fail. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Worp, H.B.; Howells, D.W.; Sena, E.S.; Porritt, M.J.; Rewell, S.; O’Collins, V.; Macleod, M.R. Can animal models of disease reliably inform human studies? PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.J.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Longo, D.L.; de Cabo, R. Animal models of aging research: Implications for human aging and age-related diseases. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2015, 3, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.J.; Andrews, N.; Ball, D.; Bellantuono, I.; Gray, J.; Hachoumi, L.; Holmes, A.; Latcham, J.; Petrie, A.; Potter, P.; et al. Does age matter? The impact of rodent age on study outcomes. Lab. Anim. 2017, 51, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesch, G.H.; Allen, T.J. Rodent Models of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy. Nephrology 2007, 12, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Sui, B.; Xiang, L.; Yan, X.; Wu, D.; Shi, S.; Hu, X. Emerging understanding of apoptosis in mediating mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Baust, J.M. Cryopreservation: An emerging paradigm change. Organogenesis 2009, 5, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Diabetes and gender. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]