2. Chromosomes in Meiosis and Mitosis

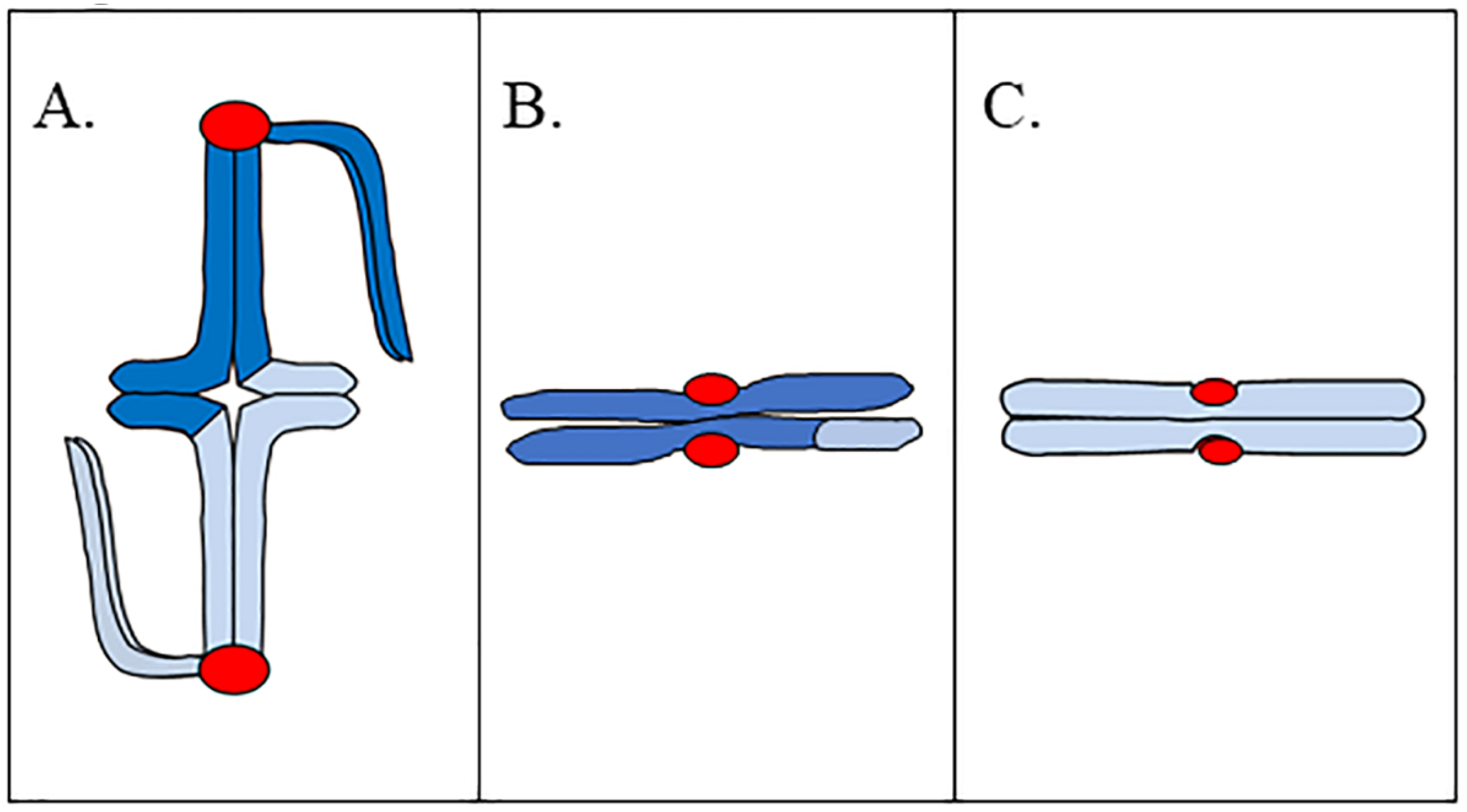

Understanding the pre-metaphase stretch phenomenon requires a general understanding of how chromosomes are built in meiosis I, meiosis II, and mitosis. Bivalents are composed of two pairs of sister chromatids that are connected as a result of sister-chromatid cohesion and recombination (

Figure 1A).

In meiosis I, sister kinetochores are fused together, thus one pair of sister chromatids associates with one spindle pole, while the homologous pair associates with the opposite pole in metaphase I. This helps to ensure that one pair of sister chromatids will pass together to the same spindle pole, while the homologous pair passes to the opposite pole in anaphase I. One key feature of bivalent structure is that the bivalent is built such that there is a substantial length of chromatin between homologous kinetochores. In some cases, the distance between homologous kinetochores is the full length of two chromosome arms; and our preliminary observations of living metaphase I spermatocytes of praying mantids (an organism that exhibits pre-metaphase stretch) shows that the distance between homologous kinetochores ranges from 3 to 7 μm [

5]. A meiosis II chromosome is composed of two sister chromatids, with sister kinetochores now facing in opposite directions (

Figure 1B); which helps to ensure that sister chromatids separate from one another in anaphase II. Similar to chromosomes in meiosis II, mitotic chromosomes are composed of two sister chromatids, with sister kinetochores facing in opposite directions (

Figure 1C). As with meiosis II, this helps to ensure that sister chromatids separate from one another in mitotic anaphase. Both meiosis II and mitotic chromosomes separate their sister kinetochores by two chromosome widths. Our preliminary observations of meiosis II in mantid spermatocytes show that the distance between sister kinetochores is approximately 2 μm [

5]. While we do not have data describing interkinetochore distances in mantid mitosis, interkinetochore distance in bioriented mitotic chromosomes of PtK2 cells is approximately 3 μm in chromosomes with a bipolar attachment to the spindle [

6].

Not only is there a difference in distance between kinetochores in bivalents and meiosis II/mitosis chromosomes, the chromatin separating sister kinetochores is different. The chromatin separating sister kinetochores in mitosis/meiosis II makes up the inner centromere; a region of highly elastic heterochromatin [

7]. The large length of chromatin separating homologous kinetochores in meiosis I includes highly condensed non-centromeric chromatin.

3. The Pre-Metaphase Stretch

While Darlington [

1] stated in his 1937 book, Recent Advances in Cytology, that chromosomes reach their maximum condensation in late prophase, a number of even earlier publications revealed a more complex series of events prior to metaphase in meiosis I. In 1901, de Sinéty published a comprehensive biological and anatomical description of several species of phasmids (stick insects) that included cytological data [

8]. De Sinéty’s publication included camera-lucida drawings of multiple stages of spermatocytes. Figures of prometaphase I and metaphase I in the spermatocytes of the phasmid

Leptynia attenuata, revealed that bivalents on a prometaphase I spindle were substantially longer than metaphase I bivalents. In the main text of this extensive work and in his footnotes, de Sinéty notes that the stretched appearance of chromosomes might be the result of an atypical variant of metaphase chromosome behavior. M.J.D. White, in 1941, was the first to explicitly describe that chromosomes in prometaphase I spermatocytes of some species of praying mantids undergo “violent stretching” [

9]. Sally Hughes-Schrader’s pioneering work on chromosome behaviors in meiosis I expanded upon White’s description.

Hughes-Schrader studied meiosis in a broad range of organisms, making seminal discoveries over her more than 50-year long career that increased our understanding of the variety of ways chromosomes can be structured and can interact with the spindle. By studying particular cytogenetic phenomena in multiple members of multiple taxonomic groups, Hughes-Schrader was able to study the oddities of chromosomes in addition to offering evolutionary insight to the development of different chromosome structures and behaviors. In the 1940s and 1950s, Hughes-Schrader turned her attention to studying the stretching of prometaphase I bivalents in her study of meiosis in male praying mantids, observing the same “violent stretching” of bivalents that M.J.D. White saw in his earlier work [

9,

10]. A later study of phasmids showed meiosis I bivalents also exhibited this stretching phenomenon (as de Sinéty initially observed and briefly noted), and Hughes-Schrader called this the “pre-metaphase stretch”. Hughes-Schrader showed in both praying mantids and phasmids that, just prior to nuclear envelope breakdown, bivalents appear to unfold, separating homologous kinetochores from one another. In some cases, the bivalents also interact with the spindle poles through an intact nuclear envelope at this time [

10]. Upon nuclear envelope breakdown, both phasmid and praying mantid bivalents associate with an already-existing bipolar spindle (behavior of bivalents in meiosis, including the pre-metaphase stretch is shown as a drawing in

Figure 2A). If bivalents formed a bipolar attachment, they exhibited the pre-metaphase stretch, and the stretch was the most extreme in bivalents placed at the center of the spindle—some only had a thin segment of chromatin connecting homologues (this can be observed in

Figure 2B) [

4,

10]. The stretch appears “asynchronous” across all bivalents, with some bivalents strongly stretched and others unstretched (

Figure 2A,B) [

4,

10]. In mantids, bivalents experienced the pre-metaphase stretch and congressed to the metaphase plate concurrently [

10,

11]. When bivalents achieved a metaphase I alignment, they contracted substantially (

Figure 2A,B) [

10,

11]. Hughes Schrader noted that praying mantid bivalents experiencing the pre-metaphase stretch had a rough outline, while contracted, metaphase bivalents had a smooth outline [

10]. In contrast to observations in praying mantids, in phasmids, the stretching of the region between sister kinetochores was observed in some species in meiosis II, and the pre-metaphase stretch stage appeared to be complete prior to full metaphase I alignment (

Figure 2B) [

4]. To extend these results, Matthey demonstrated that blattids (cockroaches) also demonstrate the pre-metaphase stretch, and Hughes-Schrader noted when discussing the phenomenon that blattids, similar to praying mantids, undergo a pre-metaphase stretch and chromosome congression concurrently [

4,

12].

It is important to note that Hughes-Schrader and others who reported on pre-metaphase stretch studied fixed, stained specimens at different time points during meiosis I in the spermatocytes of multiple species of praying mantids and phasmids [

4,

10]. Based on careful evaluation of these fixed, stained images, it could be determined that the pre-metaphase stretch occurred after nuclear envelope breakdown and before/during congression to the metaphase plate [

4,

10], although Hughes-Schrader was unable to view the stretch in living cells and thus no precise length of time for the stretch stage could be determined. Hughes-Schrader did make estimates of the relative amount of time spent in various stages of meiosis (including stretch) based on the quantity of cells in a particular section that were in that phase. She reasoned that phases observed more abundantly took longer, and would make general conclusions about the relative timing of each phase [

10]. That said, the ordering and timing of chromosome movements and the pre-metaphase stretch remain unknown.

Hughes-Schrader also discussed these chromosome behaviors with relation to taxonomy. At the time of these initial publications, praying mantids, phasmids, and blattids were all grouped under the insect order Orthoptera. The taxonomy has been reorganized such that they now are separate orders (Mantodea, Phasmatodea, Blattodea) that belong to a monophyletic group; the Polyneoptera [

13]. Not all Polyneoptera exhibit the pre-metaphase stretch. It does not appear to exist in the grasshoppers and has not even been observed in every mantid species studied by Hughes-Schrader [

10,

11]. The phenomenon is thus not universal, nor is it clade-specific. However, Hughes-Schrader postulated that the stretch might have an ancient origin due to its existence in praying mantids, phasmids, and blattids [

4]. Although the pre-metaphase stretch was originally observed in insect spermatocytes [

4,

10] it has since also been observed in oocytes of molluscs [

14], and annelid worms [

15], and spermatocytes of marsupials including the rat kangaroo

Potorous tridactylus [

16,

17]. Thus, while the pre-metaphase stretch phenomenon is not universal, it has been observed in multiple phyla of animals.

Hughes-Schrader proposed multiple factors contributing to the pre-metaphase stretch, among these early spindle formation, elongation of the spindle with bivalents attached, “repulsion” of homologous kinetochores (although she deemed this unlikely), and spindle fibers. Hughes-Schrader proposed that kinetochores play a major role in the pre-metaphase stretch, and noted a correlation between spindle elongation and extremity of chromosome stretching [

10]. Yet, chromosome interaction with the spindle cannot be the only factor that is involved in the stretch, as Matthey [

12] observed the pre-metaphase stretch within an intact nuclear envelope in cockroach primary spermatocytes.

What causes the pre-metaphase stretch? Is it due to variation of forces applied to chromosomes during cell division? Do stretched chromosomes experience a transient, greater force? Alternatively, is the pre-metaphase stretch the result of variations in chromosome architecture during progression through cell division? Is the pre-metaphase stretch and subsequent contraction associated with variation in chromosome condensation or stiffening of chromosomes as they approach metaphase? Below we will address these questions.

4. The Spindle and Kinetochores in Prometaphase

In prometaphase, dissolution of the nuclear envelope is complete, the spindle is formed, and chromosomes attach to the spindle. Unfortunately, none of the meiotic systems Hughes-Schrader and others studied have been pursued recently as model systems for studying chromosome behavior in prometaphase. However, prometaphase chromosome behaviors have been studied in some meiotic and many mitotic cell types.

In prometaphase, kinetochores bind spindle microtubules. Kinetochores and microtubules form initial, transient interactions, and reorient such that the chromosomes form bipolar attachments to the spindle. In mitotic prometaphase in many systems including yeast, diatoms, mammalian cells, newt lung cells, and meiosis I cells of yeast, the flatworm

Mesostoma ehrenbergii and some spiders, chromosomes oscillate on the spindle [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In mitotic chromosome oscillations in systems such as the newt lung epithelial cell, the movement of one kinetochore is generally well coordinated with its sister kinetochore; both kinetochores move in the same direction most of the time (e.g., when one kinetochore of a chromosome moves poleward, its sister kinetochore moves antipoleward) [

20]. In other systems such as the two species of diatoms studied by Tippit et al. and meiotic cells in

M. ehrenbergii [

19,

21], sister kinetochores are frequently uncoordinated in their movements and the lack of coordination is associated with stretching and contraction of the area between kinetochores.

During prometaphase chromosomes congress to the spindle equator, forming bipolar spindle attachments. King and Nicklas [

23] showed that the number of microtubules embedded in each kinetochore increases as grasshopper primary spermatocytes approach metaphase I. Presumably, this increase in kinetochore occupation by microtubules is associated with an increase in spindle forces applied to the kinetochore, as Hays and Salmon [

24] demonstrated through partial ablation of kinetochores in grasshopper primary spermatocytes. Hays and Salmon showed that forces applied to kinetochores by the spindle are related to the number of microtubules bound to that kinetochore, with more microtubule-kinetochore interactions equating to stronger forces on the kinetochore [

24].

While Hughes-Schrader proposed that chromosome interactions with the spindle were a possible cause for the pre-metaphase stretch [

9], spindle forces are unlikely to compose the full story. One argument against the primary role of spindle forces in the pre-metaphase stretch is that Matthey claimed to observe the pre-metaphase stretch within an intact nuclear envelope [

12]. While the nuclear envelope blocks spindle microtubules from accessing the kinetochores, there could be other cellular components applying spindle forces that could be considered to be equivalent to a kinetochore-spindle connection. The LINC complex connects parts of chromosomes to cytoskeletal elements outside the nucleus during meiotic prophase and has been implicated in stretching chromosomes in early prophase I [

25,

26]. This complex might transmit forces that stretch chromosomes through an intact nuclear envelope.

A second, and more important, argument supporting additional players beyond spindle forces in the pre-metaphase stretch is the strength of mitotic forces in prometaphase and metaphase. If attachment to the spindle were the only cause of the “violent” stretching of bivalents at prometaphase I, forces applied to kinetochores would have to be stronger in prometaphase than in metaphase. If the stretch is simply due to strong spindle forces, one would expect that chromosomes feeling forces associated with full kinetochore occupancy with microtubules (i.e., metaphase chromosomes) would be stretched the most. Intrinsic features of chromosome architecture must also play a role in pre-metaphase stretch.

5. Chromosome Architecture

Multiple features of chromosome architecture could contribute to the pre-metaphase stretch, including condensation and compaction, as well as stiffening of chromosomes. As the spindle is forming and the nuclear envelope is breaking down, chromosomes undergo massive architecture rearrangements. In mitotic prophase and in late prophase I, chromosomes condense to form individualized chromosomes. Changes in chromosome architecture are hard to study and appear variable in different systems. Early studies by Bajer [

27] demonstrated that mitotic chromosomes in the triploid endosperm of two lily species,

Haemanthus katharinae and

Leucojum aestivum, shorten substantially starting in prophase. Shortening of these chromosomes continues through late anaphase. Groups studying many other mitotic systems, including human tissue culture cells (HeLa), chicken DT-40 cells, rat kidney (NRK) cells, and fission yeast have shown that chromosomes gradually compact starting in prophase, with maximum compaction in late anaphase [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

The changes in chromosome architecture observed in mitosis are associated with the activity of several proteins, including the condensin complexes, topoisomerase IIα, and the Aurora A and B kinases.

Two complexes, condensins I and II have roles in regulating chromosome architecture in mitosis and meiosis. Both condensins share the long coiled-coil Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes proteins SMC2 and SMC4. Condensin I also has CAP-D2, CAP-G, and CAP-H [

31]. Condensin II contains subunits related to those in condensin I: CAP-D3, CAP-G2, and CAP-H2. The two condensin complexes, while containing distinct but similar components, also have different localizations and roles during cell division. Condensin II localizes to mitotic chromosomes in prophase, while condensin I is excluded from the nucleus in prophase and associates with chromosomes starting in prometaphase [

33]. In mitosis, condensin II forms the base of chromatin loops in condensing prophase chromosomes, while condensin I mediates the formation of smaller, nested chromatid loops in prometaphase, when condensin I has access to chromosomes [

30]. Chromatin architecture changes associated with condensin I binding contribute to increasing chromosome stiffness [

34]. In addition, stalling of cells in prometaphase leads to overloading of chromosomes with condensin and making the chromosomes abnormally stiff [

35], showing that time in a cell division state is associated with increases in chromosome-associated condensin complex. Attachment of condensin I to chromosomes starts in prometaphase and continues through anaphase [

36].

Activity of the condensin complexes has also been studied in male meiosis in

Drosophila melanogaster. Interestingly, some components of condensin II are missing in

Drosophila and a number of other insect lineages, so it is not clear how condensins work in prophase of meiosis—a time when condensin II is bound to chromosomes in other systems [

37]. All condensin I components are present in

D. melanogaster. Condensin I appears to adopt the same localization pattern in

Drosophila male meiosis as it adopts in mitosis. It is excluded from the nucleus and localizes to bivalents in prometaphase I. Condensin I is required for accurate segregation of chromosomes in meiosis I [

38]. The application of what was learned in

Drosophila male meiosis to systems with pre-metaphase stretch is not clear. We do not know whether praying mantids and phasmids have all components of condensin II, nor do we know its potential role in regulating chromosome architecture in the pre-metaphase stretch. Cockroaches, which exhibit pre-metaphase stretch do have all the components of condensin II [

37], so perhaps both condensin complexes play a role in regulating the pre-metaphase stretch.

Condensin I association with mitotic chromosomes is linked to activity of a number of proteins. The Aurora B kinase is required for binding of condensin I to chromosomes and phosphorylates the non-SMC subunits of condensin I [

34]. Interestingly, the chromokinesin KIF4A also interacts with condensin I, and this interaction is required for correct and timely chromosome congression in prometaphase in HeLa cells, suggesting an important link between changes in chromosome architecture and chromosome congression [

39]. KIF4A interaction with condensin I depends on activity of the Aurora A kinase [

39]. In addition, topoisomerase IIα is required both for chromosome compaction and individualization of sister chromatids in prometaphase, as shown in the human colorectal carcinoma cell line HCT116 [

2].

Data from experiments in which topoisomerase IIα is depleted inform our knowledge of its critical role in prometaphase. The microtubule poison nocodazole was used to arrest modified HCT116 cells in mitotic prometaphase [

2]. In these arrested prometaphase cells, chromatin volume reduced over time, indicating gradual, continued chromosome condensation in prometaphase. When topoisomerase IIα was rapidly degraded in these same prometaphase-arrested cells, chromatin volume did not decrease [

2]. Depletion of topoisomerase IIα in asynchronous cultures not treated with nocodazole showed similar results, as chromatin volume did not reduce as cells progressed through prometaphase [

2]. These results support a role for topoisomerase IIα in prometaphase chromosome condensation. Nielsen et al. suggest that topoisomerase IIα works with condensin I, as the condensin I concentration on the prometaphase chromosome slowly increases, to lock chromosomes in a condensed state that helps to disentangle sister chromatids and thus allow subsequent, easy sister chromatid separation in anaphase [

2].

There are other contributors to changes in chromosome architecture through cell division beside the condensins and their partners. Histone modifications are also implicated in the cell-cycle associated chromosome condensation and may affect chromosome length and stiffness during mitosis (these modifications may be impacted by the activity of Aurora B, which acts as a histone kinase) [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. In addition, chromosomes may not just gradually compact from prophase to anaphase. Chromosomes in a range of systems exhibit cycles of expansion and contraction during prophase that might offer some explanation for the pre-metaphase stretch. Kleckner et al. [

43], in describing meiotic prophase, noted that crossing over causes a significant amount of stress on chromosomes; this strain is redistributed along the chromosome, which helps to explain why no chiasmata are formed right next to one another. Other events required for initiating cell division could also strain chromosomes. Expansion-contraction cycles can relieve this strain [

43]. Liang and colleagues [

3] called this “chromosome stress cycling,” and showed cycles of expansion and contraction during prophase in multiple mitotic systems, stating that chromatin—when unconstrained—will take up the volume that allows optimization of entropy and interactions. If fibers become constrained due to inter-fiber tethers causing them to occupy a volume that is too small, then these tethers can be released, causing expansion and stress relief [

3]. Examples of such tethers include cohesin, condensin, RNAs, histone-histone contacts, and topoisomerase II-mediated catenations [

3]. While these cycles of expansion and contraction were observed in prophase, stress cycling could extend to prometaphase in systems that exhibit pre-metaphase stretch.

6. Stretch between Kinetochores in Mitosis, Meiosis II, and the Pre-Metaphase Stretch

Chromosome condensation, as described above, leads to shrinkage of the full length of chromosomes. The changes in chromosome architecture stimulated by the activity of the condensin complexes also lead to stiffening of chromosomes and the stiffening increases as the quantity of bound condensin increases [

35]. Pre-metaphase stretch could be the result of stress cycling of prometaphase I bivalents prior to their strong metaphase compaction. Alternatively, the pre-metaphase stretch could exist because prometaphase chromosomes in the systems studied are more elastic than metaphase chromosomes, and are thus more susceptible to stretching by the spindle as a result of an early bipolar attachment. Hughes-Schrader observed stretching between sister kinetochores in prometaphase II spermatocytes with no obvious prometaphase II length expansion in chromosome length in some phasmids [

4]. Hughes-Schrader considered this a meiosis II equivalent for pre-metaphase stretch [

4]. The lack of a visible expansion in prometaphase II chromosome length suggests that the centromere is more elastic, allowing the stretching to occur. Similar stretching of centromere regions has been observed in some systems in chromosomes in mitosis.

An understanding of mitotic chromosome architecture between kinetochores in prometaphase combined with movements on the spindle could offer insight. While chromosomes are compacting in prometaphase, as described above, the chromosomes may also be oscillating, and experiencing forces that stretch the region between kinetochores. Attachment to the spindle stretches the centromere area between kinetochores, and this stretching is seen in oscillating chromosomes [

19]. Centromere stretching appears to be necessary for satisfying the spindle checkpoint and ultimately correctly segregating chromosomes in anaphase [

44]. Depletion of condensin I leads to an increase in centromere stretch in HeLa cells (with a phenotype reminiscent of the centromere stretch observed by Hughes-Schrader in prometaphase II spermatocytes in phasmids) [

36], suggesting that in vivo variation in condensin I concentration at the centromere could lead to variations in centromere stretching. Variation in inter-kinetochore distance is the closest equivalent to the pre-metaphase stretch seen in mitosis. The stretched mitotic kinetochores look very similar to the still images observed in phasmid prometaphase II, and may help to explain the pre-metaphase stretch since there are few detailed studies of the changes in chromosome architecture and behavior in meiosis.

The pre-metaphase stretch was observed in meiosis I bivalents. The two homologous kinetochores of a bivalent are separated by a large amount of chromosome volume and distance; sometimes two full chromosome arm lengths separate the homologous kinetochores (

Figure 1A). The two sister kinetochores of a meiosis II or mitotic chromosome are separated by two chromosome widths (

Figure 1B,C), a much shorter distance. Because effects of stretching are more apparent on a large bivalent than on a smaller mitotic chromosome, and because prometaphase I can take hours to complete [

5], systems that exhibit pre-metaphase stretch offer a great opportunity to study the fine details of prometaphase chromosome compaction, stiffening, and behavior. They are ideal systems for detecting and measuring changes in chromatin volume, and for directly measuring the physical properties of chromosomes such as Young’s Modulus, in addition to forces applied on the kinetochore. They are worth a second look as a model for studying how chromosome architecture and behavior change during cell division.