Current Trends in Synthesis and Characterization of Biomass-Based Materials for CO2 Capture

Abstract

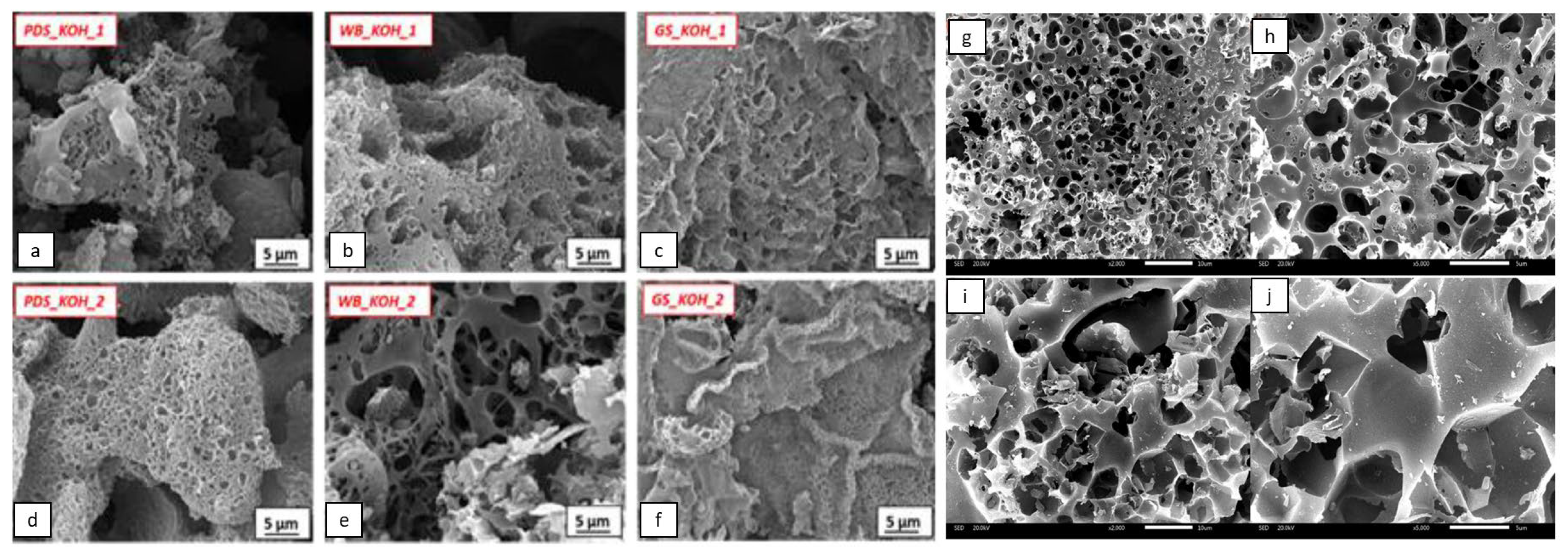

1. Introduction

2. Biomass

2.1. Types of Biomasses for CO2 Adsorption

2.2. Synthesis of Porous Adsorbents from Biomass

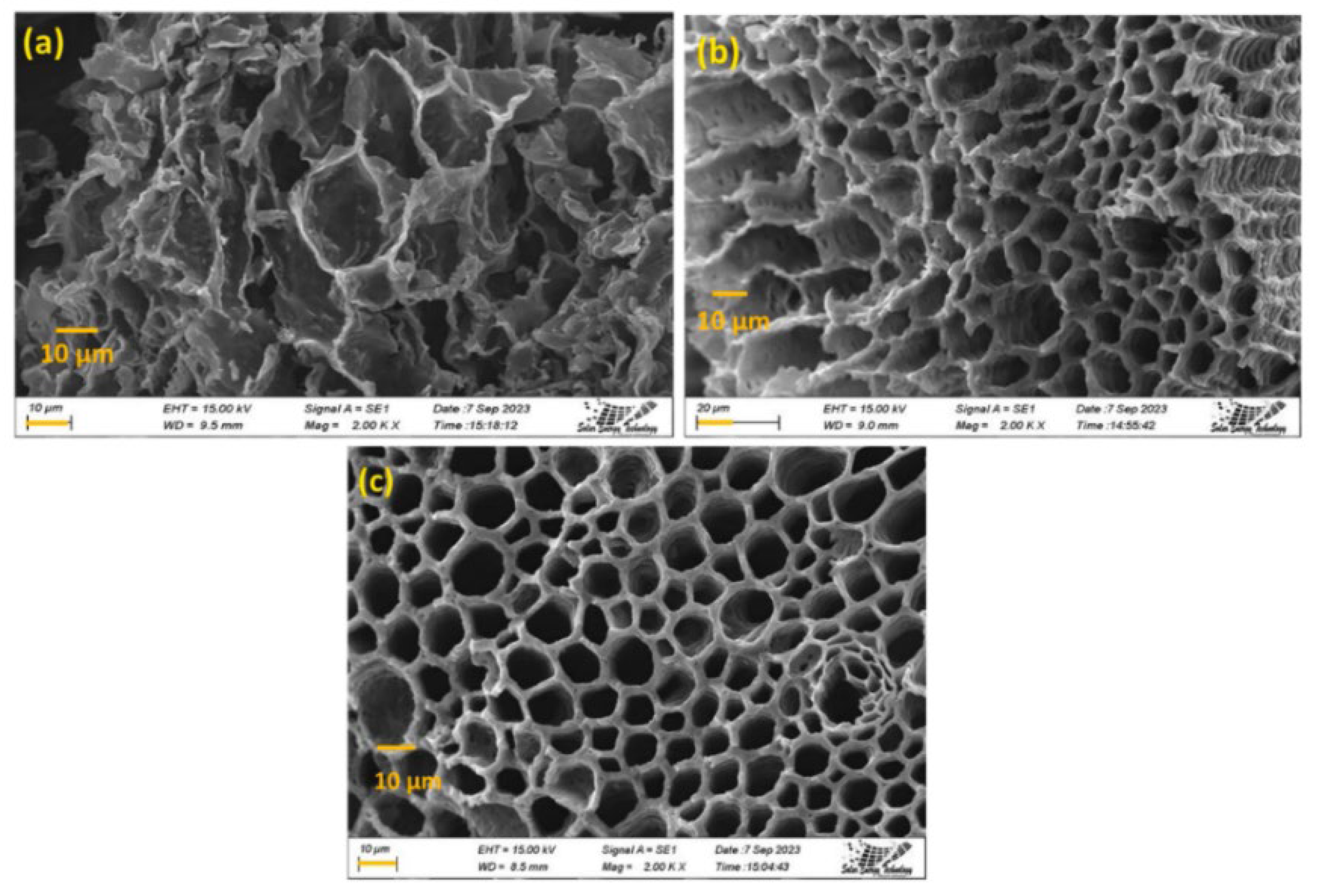

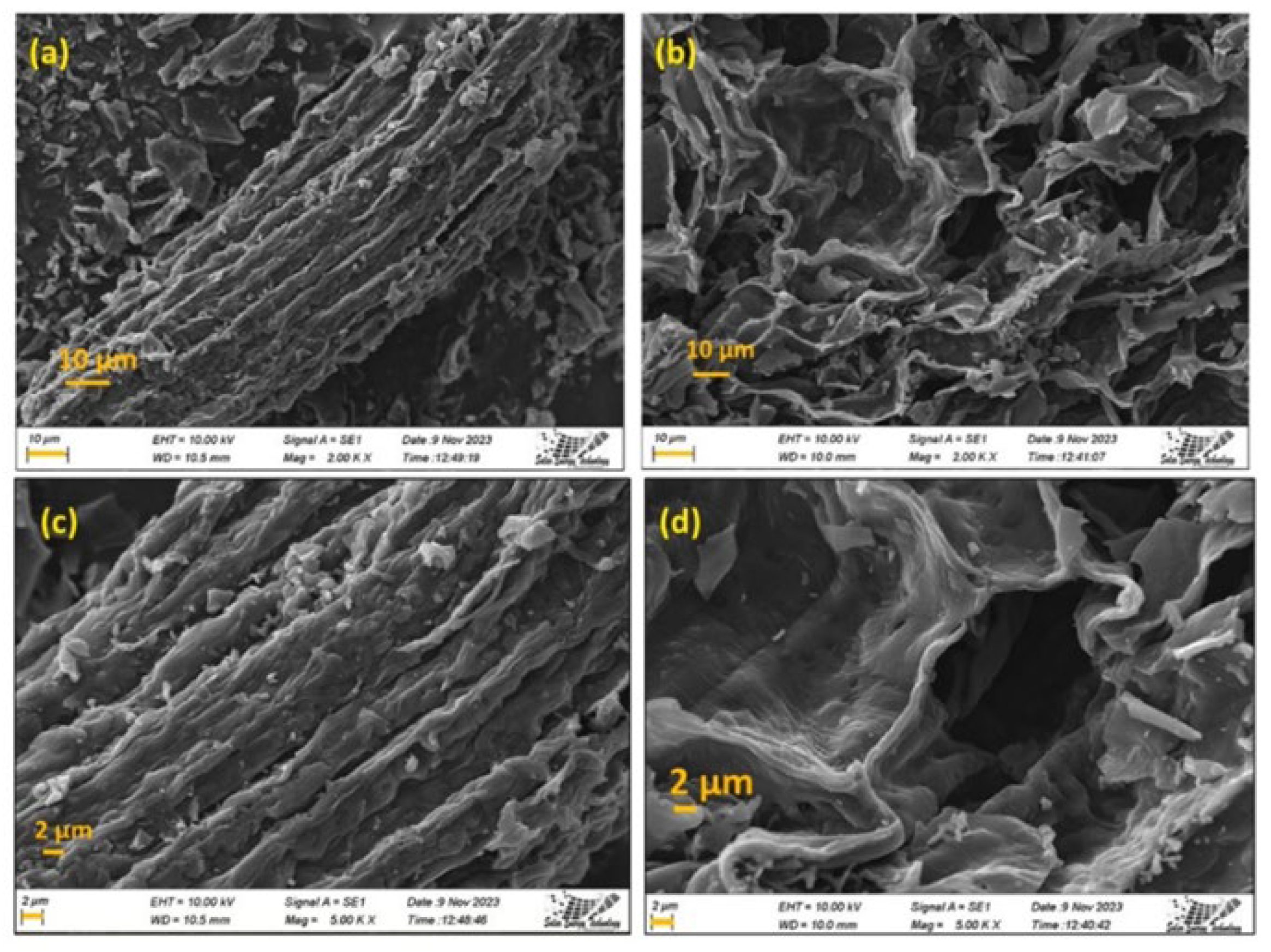

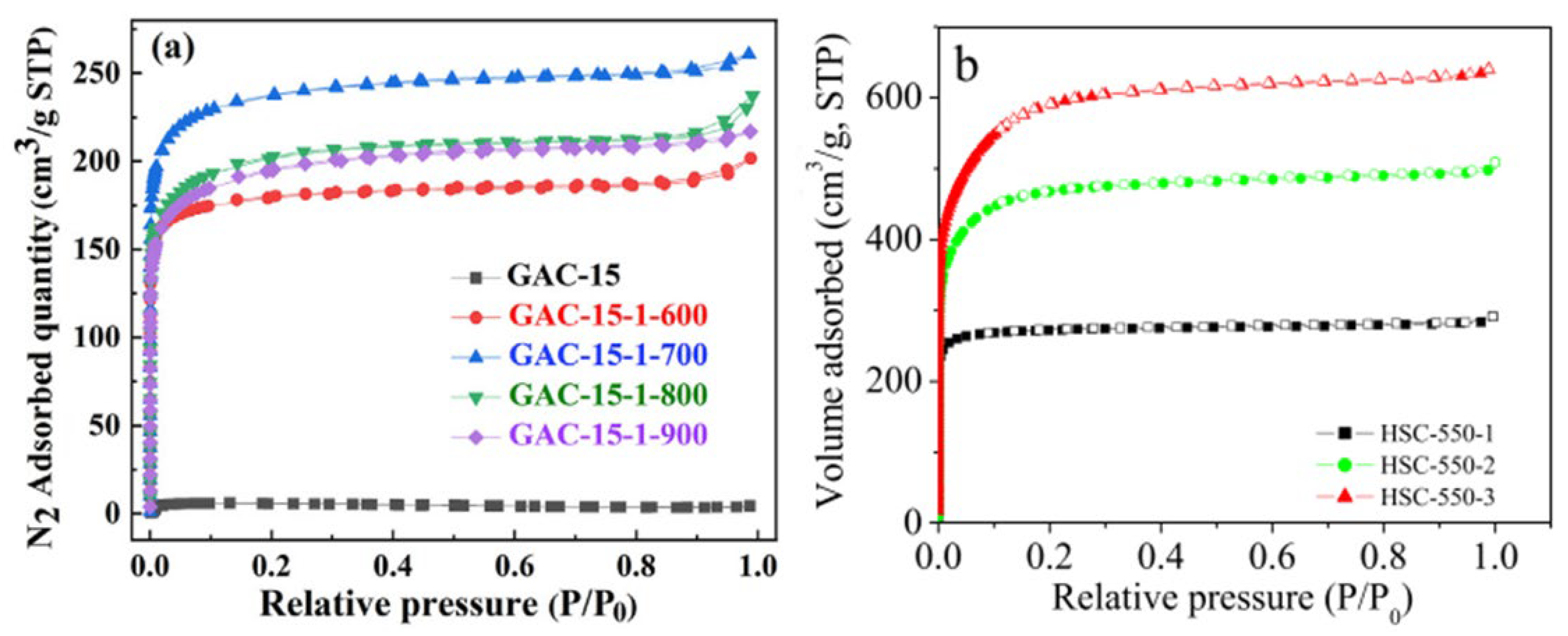

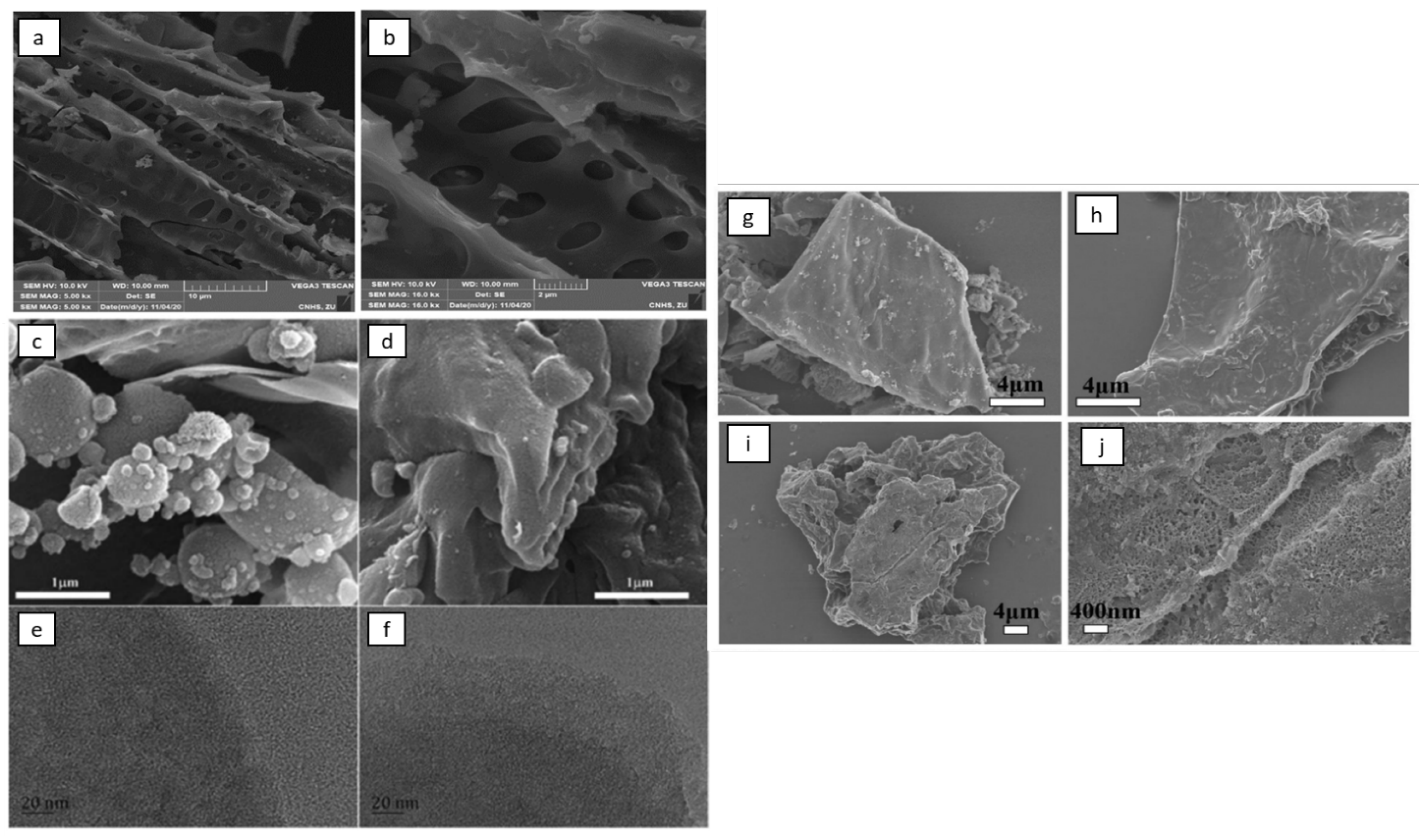

2.3. Characterization of Biomass-Based Adsorbents

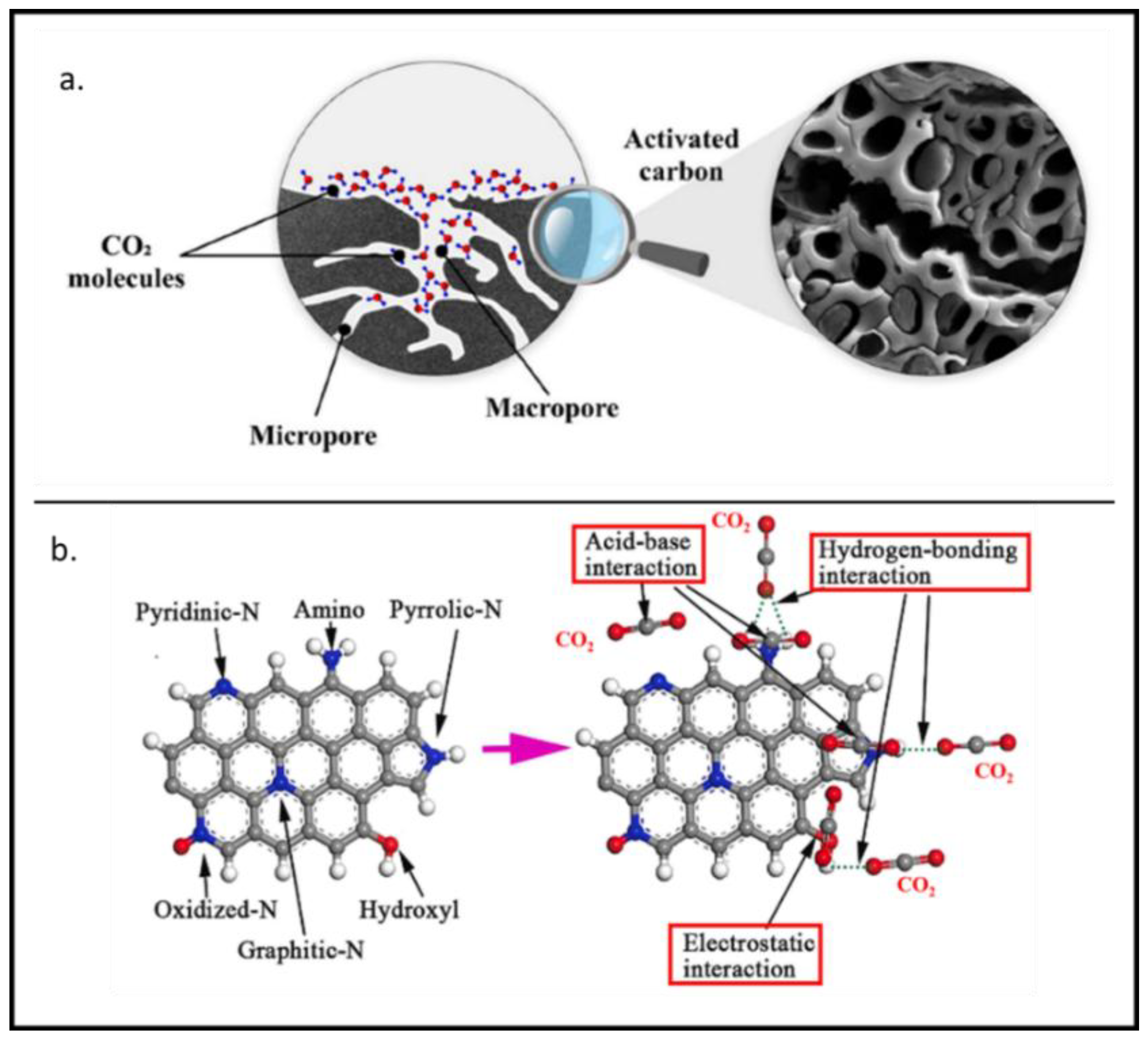

3. Mechanisms of CO2 Capture

4. Performance Evaluation

5. Summary and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anwar, M.N.; Fayyaz, N.; Sohail, F.; Khokhar, M.F.; Baqar, M.; Khan, W.D.; Rasool, K.; Rehan, M.; Nizami, A.S. CO2 capture and storage: A way forward for sustainable environment. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 226, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, R. Global Temperature Report for 2024. Available online: https://berkeleyearth.org/global-temperature-report-for-2024/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Hannah Ritchie, P.R.M.R. CO2 and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Charisiou, N.D.; Douvartzides, S.L.; Goula, M.A. Biogas Sweetening Technologies. In Engineering Solutions for CO2; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, G.; Priya, A.K.; Gnanasekaran, L.; Rajendran, S.; Hoang, T.K.A. Biomass and waste derived silica, activated carbon and ammonia-based materials for energy-related applications—A review. Fuel 2024, 355, 129490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Gong, Y.; Li, D.; Pan, C. Biomass-derived porous carbon materials: Synthesis, designing, and applications for super-capacitors. Green. Chem. 2022, 24, 3864–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biomass. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/renewable-energy/bioenergy/biomass_en (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Khandaker, T.; Islam, T.; Nandi, A.; Anik, M.A.A.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Hasan, M.K.; Hossain, M.S. Biomass-derived carbon materials for sustainable energy applications: A comprehensive review. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 9, 693–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Q.; Feng, D.; Dong, H.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xie, M. Ultra-microporous biochar-based carbon adsorbents by a facile chemical activation strategy for high-performance CO2 adsorptio. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 241, 107613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbounov, M.; Petrovic, B.; Ozmen, S.; Clough, P.; Masoudi Soltani, S. Activated carbon derived from Biomass combustion bottom ash as solid sorbent for CO2 adsorption. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 194, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; He, Y.; Shao, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, H. Biomass-derived functional carbon material for CO2 adsorption and electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 9, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goskula, S.; Siliveri, S.; Gujjula, S.R.; Adepu, A.K.; Chirra, S.; Narayanan, V. Development of activated sustainable porous carbon adsorbents from Karanja shell biomass and their CO2 adsorption. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2023, 14, 32413–32425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S.P.; Scarpa, F.; Fino, D.; Conti, R. Biogas purification for MCFC application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 8112–8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennersten, R.; Sun, Q.; Li, H. The future potential for Carbon Capture and Storage in climate change mitigation—An overview from perspectives of technology, economy and risk. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 103, 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslin, M.A.; Lang, J.; Harvey, F. A short history of the successes and failures of the international climate change negotiations. UCL Open Environ. 2023, 5, e059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Jindal, J.; Mittal, A.; Kumari, K.; Maken, S.; Kumar, N. Carbon materials as CO2 adsorbents: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 875–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.S.; Alsultan, M.; Sabah, A.A.; Swiegers, G.F. Carbon Dioxide Adsorption by a High-Surface-Area Activated Charcoal. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Dziejarski, B. Activated carbons—Preparation, characterization and their application in CO2 capture: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 40008–40062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.C.; Adhikari, D.K.; Goyal, H.B. Biomass-based energy fuel through biochemical routes: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, A.; Ziegler, F. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass: A summary and discussion of chemical mechanisms for process engineering. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2010, 4, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uroić Štefanko, A.; Leszczynska, D. Impact of Biomass Source and Pyrolysis Parameters on Physicochemical Properties of Biochar Manufactured for Innovative Applications. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, Y.A.; Kumari, S.; Jain, S.K.; Garg, M.C. A review on waste biomass-to-energy: Integrated thermochemical and bio-chemical conversion for resource recovery. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Peng, C. A review on renewable energy: Conversion and utilization of biomass. Smart Mol. 2024, 2, e20240019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supee, A.H.; Zaini, M.A.A. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass: A commentary. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 2024, 32, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Dziejarski, B.; Fonseca-Bermúdez, Ó.J.; Giraldo, L.; Sierra-Ramírez, R.; Bonillo, M.G.; Farid, G.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C. Bioorganic activated carbon from cashew nut shells for H2 adsorption and H2/CO2, H2/CH4, CO2/CH4, H2/CO2/CH4 selectivity in industrial applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 86, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez Negro, A.; Martí, V.; Sánchez-Hervás, J.M.; Ortiz, I. Development of Pistachio Shell-Based Bioadsorbents Through Pyrolysis for CO2 Capture and H2S Removal. Molecules 2025, 30, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahsin, M.; Shahinuzzaman, M.; Akter, T.; Abdur, R.; Bashar, M.S.; Kadir, M.R.; Hoque, S.; Jamal, M.S.; Hossain, M. Improved CO2 adsorption and desorption using chemically derived activated carbon from corn cob hard shell. Carbon Trends 2025, 19, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tang, Y.; Tang, J.; Liu, H.; Deng, J.; Sun, Z.; Ma, X. Preparation of corncob-templated carbide slag sorbent pellets by agar method for CO2 capture: One-step synthesis and cyclic performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Luo, L.; Zhao, T.; Cao, J.; Lin, Q. Chitosan-Based Porous Carbon Materials with Built-In Lewis Acid Boron Sites for Enhanced CO2 Capture and Conversion via an Electron-Inducing Effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 8644–8656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.; Shao, J.; Liu, C.; Xiao, Q.; Demir, M.; Al Mesfer, M.K.; Danish, M.; Wang, L.; Hu, X. High-performance CO2 adsorption with P-doped porous carbons from lotus petiole biomass. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J. Enhanced CO2 absorption in amine-based carbon capture aided by coconut shell-derived nitrogen-doped biochar. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidraj, J.M. Multifunctional nanoporous biocarbon derived from ginger: A promising material for CO2 capture and supercapacitor. Energy Mater. 2025, 5, 500016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskolczi, N.; Gao, N.; Quan, C.; Laszlo, A.T. CO2 reduction by chars obtained by pyrolysis of real wastes: Low temperature adsorption and high temperature CO2 capture. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Xu, W.; Ma, X.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Li, L.; Si, J. Targeted enhancement of ultra-micropore in highly oxygen-doped carbon derived from biomass for efficient CO2 capture: Insights from experimental and molecular simulation studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Yilmaz, M.; Li, J.; Yuan, S. N, S-codoped porous biochar derived from bagasse-based polycondensate for high-performance CO2 capture and supercapacitor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tan, C.; Sun, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C. Porous activated carbons derived from waste sugarcane bagasse for CO2 adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Malki, M.; Yaser, A.Z.; Hamzah, M.A.A.M.; Zaini, M.A.A.; Latif, N.A.; Hasmoni, S.H.; Zakaria, Z.A. Date Palm Biochar and Date Palm Activated Carbon as Green Adsorbent—Synthesis and Application. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2023, 9, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazmi, A.; Nicolae, S.A.; Modugno, P.; Hasanov, B.E.; Titirici, M.M.; Costa, P.M.F.J. Activated carbon from palm date seeds for CO2 capture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, I.B.; Saleh, M.B.; Iqbal, J.; El Gamal, M.; Hameed, S. Date palm waste pyrolysis into biochar for carbon dioxide adsorption. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolae, S.A.; Louis-Therese, J.; Gaspard, S.; Szilágyi, P.Á.; Titirici, M.M. Biomass derived carbon materials: Synthesis and application towards CO2 and H2S adsorption. Nano Sel. 2022, 3, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Luo, H. Preparation of pistachio shell-based porous carbon and its adsorption performance for low concentration CO2. Particuology 2024, 95, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, Z.; Kaya, N.; Topcu, Y.; Uzun, H. Pyrolysis and optimization of chicken manure wastes in fluidized bed reactor: CO2 capture in activated bio-chars. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 130, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Huang, Y.Y. Valorization of coffee grounds to biochar-derived adsorbents for CO2 adsorption. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Lv, H.; Li, B.; Wu, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, C. One-Step Synthesis of Microporous Carbon Monoliths Derived from Biomass with High Nitrogen Doping Content for Highly Selective CO2 Capture. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, W.; Xue, R.; Su, C.; Su, R.; Li, X.; Zeng, Z.; Li, L. Effect of mechanical compaction and nitrogen doping treatment on ultramicropore structure of biomass-based porous carbon and the mechanism of CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 303, 120995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.C.; Li, J.; He, G.; Yuan, S. N, P co-doped cellulose-based carbon aerogel: A dual-functional porous material for CO2 capture and supercapacitor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, W.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z. Enhancing CO2 capture with K2CO3-activated carbon derived from peanut shell. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 183, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Bermúdez, Ó.J.; Giraldo, L.; Sierra-Ramírez, R.; Serafin, J.; Dziejarski, B.; Bonillo, M.G.; Farid, G.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C. Cashew nut shell biomass: A source for high-performance CO2/CH4 adsorption in activated carbon. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 83, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Cai, W.; Verpoort, F.; Zhou, J. Preparation of pineapple waste-derived porous carbons with enhanced CO2 capture performance by hydrothermal carbonation-alkali metal oxalates assisted thermal activation process. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 146, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyjoo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhong, H.; Tian, H.; Pan, J.; Pareek, V.K.; Jiang, S.P.; Lamonier, J.F.; Jaroniec, M.; Liu, J. From waste Coca Cola® to activated carbons with impressive capabilities for CO2 adsorption and supercapacitors. Carbon 2017, 116, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ello, A.S.; De Souza, L.K.C.; Trokourey, A.; Jaroniec, M. Coconut shell-based microporous carbons for CO2 capture. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 180, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedli, H.; Almonnef, M.; Rabhi, R.; Mbarek, M.; Abdessalem, J.; Slimi, K. Activated Carbon as an Adsorbent for CO2 Capture: Adsorption, Kinetics, and RSM Modeling. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 2080–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, S.; He, S.; Wu, C. Direct air capture of CO2 by KOH-activated bamboo biochar. J. Energy Inst. 2022, 105, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Lv, Y. Nitrogen-doped porous carbons derived from sustainable biomass via a facile post-treatment nitrogen doping strategy: Efficient CO2 capture and DRM. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 24388–24397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jiang, Y.; Balasubramanian, R. Synthesis, formation mechanisms and applications of biomass-derived carbonaceous materials: A critical review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 24759–24802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogungbenro, A.E.; Quang, D.V.; Al-Ali, K.A.; Vega, L.F.; Abu-Zahra, M.R. Synthesis and characterization of activated carbon from biomass date seeds for carbon dioxide adsorption. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Sun, S.; Huang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, X.; Wu, S. KOH Activation Mechanism in the Preparation of Brewer’s Spent Grain-Based Activated Carbons. Catalysts 2024, 14, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedynak, K.; Charmas, B. Adsorption properties of biochars obtained by KOH activation. Adsorption 2024, 30, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, F.; Dou, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Xia, Y.; Tu, B.; Zhao, D. A comprehensive study on KOH activation of ordered mesoporous carbons and their supercapacitor application. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smedt, J.; Arauzo, P.J.; Maziarka, P.; Ronsse, F. Adsorptive carbons from pinewood activated with a eutectic mixture of molten chloride salts: Influence of temperature and salt to biomass ratio. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smedt, J.; Soroush, S.; Heynderickx, P.M.; Arauzo, P.J.; Ronsse, F. The feasibility of activated carbon derived from waste seaweed via molten salt activation in a eutectic mixture of ZnCl2-NaCl-KCl for adsorption of anionic dyes. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2024, 15, 2891–12903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, R.; Li, G.; Hu, C. The role of H3PO4 in the preparation of activated carbon from NaOH-treated rice husk residue. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 32626–32636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taurbekov, A.; Abdisattar, A.; Atamanov, M.; Yeleuov, M.; Daulbayev, C.; Askaruly, K.; Kaidar, B.; Mansurov, Z.; Castro-Gutierrez, J.; Celzard, A.; et al. Biomass Derived High Porous Carbon via CO2 Activation for Supercapacitor Electrodes. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Khandaker, T.; Anik, M.A.A.M.; Hasan, M.K.; Dhar, P.K.; Dutta, S.K.; Latif, M.A.; Hossain, M.S. A comprehensive review of enhanced CO2 capture using activated carbon derived from biomass feedstock. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 29693–29736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fan, W.; Xu, Y. Synthesis and characterisation of K2CO3-activated carbon produced from distilled spent grains for the adsorption of CO2. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 34726–34737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Guo, X.; Xu, Y. Designing a novel N-doped adsorbent with ultrahigh selectivity for CO2: Waste biomass pyrolysis and two-step activation. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2021, 11, 2843–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, T.; Lu, M.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, W. Sustainable lignin-derived hierarchical mesoporous carbon synthesized by a renewable nano-calcium carbonate hard template method and its utilization in zinc ion hybrid supercapacitors. Green. Chem. 2024, 26, 5441–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Man, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J. Hard template synthesis of Zn, Co co-doping hierarchical porous carbon framework for stable Li metal anodes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 637, 157902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhao, B.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Pak, T.; Li, G. Preparation of mesoporous batatas biochar via soft-template method for high efficiency removal of tetracycline. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolae, S.A.; Szilágyi, P.Á.; Titirici, M.M. Soft templating production of porous carbon adsorbents for CO2 and H2S capture. Carbon 2020, 169, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Mao, X.; Wang, J.; Liang, C.; Liang, J. Preparation of rice husk-derived porous hard carbon: A self-template method for biomass anode material used for high-performance lithium-ion battery. Chem. Phys. 2021, 551, 111352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Xiao, Z.; Zhai, S.; Wang, S.; Lv, H.; Niu, W.; Zhao, Z.; An, Q. Defect-rich N-doped porous carbon derived from alginate by HNO3 etching combined with a hard template method for high-performance supercapacitors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 260, 124121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ma, R.; Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Radosz, M.; Fan, M. CO2 Adsorption on Hazelnut-Shell-Derived Nitrogen-Doped Porous Carbons Synthesized by Single-Step Sodium Amide Activation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 7046–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, A.; Aziz, M.A.; Helal, A.; Abdelnaby, M.M.; Khan, A.; Theravalappil, R.; Khan, M.Y. CO2 Adsorption on Biomass-Derived Carbons from Albizia procera Leaves: Effects of Synthesis Strategies. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 36228–36236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhou, T.; Wang, J.; Rego, F.; Yang, Y.; Xiang, H.; Yin, Y.; Liu, W.; Bridgwater, A.V. CO2 adsorption on Miscanthus × giganteus (MG) chars prepared in different atmospheres. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 52, 101670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Ye, Q.; Wu, K.; Wang, L.; Dai, H. Highly efficient CO2 adsorption of corn kernel-derived porous carbon with abundant oxygen functional groups. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 51, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Peng, W.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Shao, J.; Hu, X. Preparation of biomass-derived porous carbons by a facile method and application to CO2 adsorption. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 116, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Lu, T.; Shao, J.; Huang, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, L. Biomass derived nitrogen and sulfur co-doped porous carbons for efficient CO2 adsorption. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 281, 119899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Ji, J.; Ji, X. Renewable N-doped microporous carbons from walnut shells for CO2 capture and conversion. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 4701–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Shao, J.; Hu, X. Efficient nitrogen doped porous carbonaceous CO2 adsorbents based on lotus leaf. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 103, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Chen, G.; Xiao, H.; Shi, G.; Ruan, C.; Ma, Y.; Dai, H.; Yuan, B.; Chen, X.; Yang, X. Facile preparation of N-doped activated carbon produced from rice husk for CO2 capture. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2021, 582, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Strømme, M. Sustainable Porous Carbon Materials Derived from Wood-Based Biopolymers for CO2 Capture. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.C.; Nighojkar, A.; Kandasubramanian, B. Relevance of wood biochar on CO2 adsorption: A review. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 3, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Yan, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y. Nitrogen-doped porous carbon through K2CO3-activated bamboo shoot shell for an efficient CO2 adsorption. Fuel 2024, 363, 130937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wu, C.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, G. Synthesis and characterization of magnetic K2CO3-activated carbon produced from bamboo shoot for the adsorption of Rhodamine b and CO2 capture. Fuel 2023, 332, 126107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Dziejarski, B.; Vendrell, X.; Kiełbasa, K.; Michalkiewicz, B. Biomass waste fern leaves as a material for a sustainable method of activated carbon production for CO2 capture. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 175, 106880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, X.; Song, S.; Sun, M.; Xue, Y.; Yang, G. Preparation of Nitrogen-Doped Cellulose-Based Porous Carbon and Its Carbon Dioxide Adsorption Properties. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24814–24825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Bao, A. Preparation of cellulose carbon material from cow dung and its CO2 adsorption performance. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 68, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phromphithak, S.; Onsree, T.; Shariati, K.; Drummond, S.; Katongtung, T.; Tippayawong, N.; Naglic, J.; Lauterbach, J. Low-transition temperature mixtures pretreatment and hydrothermal carbonization of corncob residues for CO2 capture materials. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lee, Y.-R.; Won, Y.; Kim, H.; Jeong, S.-E.; Hwang, B.W.; Cho, A.R.; Kim, J.-Y.; Park, Y.C.; Nam, H.; et al. Development of high-performance adsorbent using KOH-impregnated rice husk-based activated carbon for indoor CO2 adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 437, 135378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R.; Jha, M.K.; Guchhait, S.K.; Sutradhar, D.; Yadav, S. Impact of KOH Activation on Rice Husk Derived Porous Activated Carbon for Carbon Capture at Flue Gas alike Temperatures with High CO2/N2 Selectivity. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 4802–4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.-A.; Yang, F.; Zhong, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Guo, Z.; Lv, G.; Yang, J.; Yuan, A.; Pan, J. Ultra-microporous cotton fiber-derived activated carbon by a facile one-step chemical activation strategy for efficient CO2 adsorption. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 324, 124470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jia, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Huo, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Z. Heteroatom-doped biochar devised from cellulose for CO2 adsorption: A new vision on competitive behavior and interactions of N and S. Biochar 2023, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhi, Y.; Yu, Q.; Tian, L.; Demir, M.; Colak, S.G.; Farghaly, A.A.; Wang, L.; Hu, X. Sulfur-Enriched Nanoporous Carbon: A Novel Approach to CO2 Adsorption. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 5434–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xu, D.D.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, C. Multi-response optimization of sewage sludge-derived hydrochar production and its CO2-assisted gasification performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tang, S.; Chen, J.P. Carbon capture and utilization by algae with high concentration CO2 or bicarbonate as carbon source. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Yan, Q. In-situ pyrolysis of Taihu blue algae biomass as appealing porous carbon adsorbent for CO2 capture: Role of the intrinsic N. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 145424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Gao, N. Biomass-based carbon materials for CO2 capture: A review. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 68, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: Pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ma, C.; Xu, M.; Wang, S.; Xu, L. Recent Advances in CO2 Adsorption from Air: A Review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2019, 5, 272–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Li, T.; Li, H.; Dang, A.; Han, Y. Carbon-based adsorbents for CO2 capture: A systematic review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 147, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, X.Y.D.; Lee, J.J.C.; Wu, W.Y.; Tao, L.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Q.; Bu, J. Advancements in CO2 capture by absorption and adsorption: A comprehensive review. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 81, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Qu, X.; Xu, D.; Luo, Y. Porous Adsorption Materials for Carbon Dioxide Capture in Industrial Flue Gas. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 939701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raganati, F.; Miccio, F.; Ammendola, P. Adsorption of Carbon Dioxide for Post-combustion Capture: A Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 12845–12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrowshahi, M.S.; Mashhadimoslem, H.; Shayesteh, H.; Singh, G.; Khakpour, E.; Guan, X.; Rahimi, M.; Maleki, F.; Kumar, P.; Vinu, A. Natural Products Derived Porous Carbons for CO2 Capture. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2304289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, T.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Mi, J.; Meng, H.; Jin, J. Hydrophobic carbon-based coating on metal tube with efficient and stable adsorption–desorption of CO2 from wet flue gas. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 307, 122798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Huang, J.; Yu, Q.; Demir, M.; Akgul, E.; Altay, B.N.; Hu, X.; Wang, L. Fabrication of coconut shell-derived porous carbons for CO2 adsorption application. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2023, 17, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, C.; Mohan, S.; Dinesha, P. CO2 capture by adsorption on biomass-derived activated char: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igalavithana, A.D.; Choi, S.W.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Shang, J.; Wang, C.H.; Yang, X.; Kim, S.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Lee, K.B.; Ok, Y.S. Gasification biochar from biowaste (food waste and wood waste) for effective CO2 adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 391, 121147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdebenito, F.; García, R.; Cruces, K.; Ciudad, G.; Chinga-Carrasco, G.; Habibi, Y. CO2 Adsorption of Surface-Modified Cellulose Nanofibril Films Derived from Agricultural Wastes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 12603–12612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Saha, R.; Saha, S. A critical review on graphene and graphene-based derivatives from natural sources emphasizing on CO2 adsorption potential. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 67633–67663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Abd, A.; Roslee Othman, M.; Kim, J. A review on application of activated carbons for carbon dioxide capture: Present performance, preparation, and surface modification for further improvement. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 43329–43364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, T.C.; Ouyang, L.; Yuan, S. Nitrogen-doped porous carbon for excellent CO2 capture: A novel method for preparation and performance evaluation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 298, 121602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Chiueh, P.-T.; Lo, S.-L. Carbon capture of biochar produced by microwave co-pyrolysis: Adsorption capacity, kinetics, and benefits. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 22211–22221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilla Rashidi, N.; Bokhari, A.; Yusup, S. Evaluation of kinetics and mechanism properties of CO2 adsorption onto the palm kernel shell activated carbon. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 33967–33979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Gutiérrez, N.; Gil, M.V.; Rubiera, F.; Pevida, C. Adsorption performance indicators for the CO2/CH4 separation: Application to biomass-based activated carbons. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 142, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yu, Y.; He, C.; Wang, L.; Huang, H.; Albilali, R.; Cheng, J.; Hao, Z. Efficient capture of CO2 over ordered micro-mesoporous hybrid carbon nanosphere. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Subramani, K.; Sathish, M.; Gautam, U.K. Soya derived heteroatom doped carbon as a promising platform for oxygen reduction, supercapacitor and CO2 capture. Carbon 2017, 114, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Atrach, J.; Aitblal, A.; Amedlous, A.; Clatworthy, E.B.; Honorato Piva, D.; Xiong, Y.; Guillet-Nicolas, R.; Valtchev, V. Exploring a Novel Adsorbent for CO2 Capture and Gas Separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 7119–7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Li, Z.; Ge, J.; Zhu, L.; Liu, C.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Yin, C.; Su, G. Rapid synthesis of MOF CaBTC using an ultrasonic irradiation method and its derivative materials for CO2 capture. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 9395–9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouctar, M.H.; Hassan, M.G.; Bimbo, N.; Abbas, S.Z.; Shigidi, I. Comparative Assessment and Deployment of Zeolites, MOFs, and Activated Carbons for CO2 Capture and Geological Sequestration Applications. Inventions 2025, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Dai, H.; Wei, Z.; Xie, S.; Deng, J. MOFs-based porous liquids for CO2 capture and utilization. Green. Energy Environ. 2025, 10, 1674–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Pordsari, M.A.; Tamtaji, M.; Zainali, F.; Keshavarz, S.; Baesmat, H.; Manteghi, F.; Ghaemi, A.; Rohani, S.; Iii, W.A.G. Eco-Friendly Synthesis and Morphology Control of MOF-74 for Exceptional CO2 Capture Performance with DFT Validation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, N.J.; Jaramillo, A.F.; Becker-Garcés, D.F.A.; Antileo, C.; Martínez-Retureta, R.; Martínez-Ruano, J.A.; Ñanculeo, J.; Pérez, M.M.; Cea, M. Modification of Natural and Synthetic Zeolites for CO2 Capture: Unrevealing the Role of the Compensation Cations. Materials 2025, 18, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amornsin, P.O.; Nokpho, P.; Wang, X.; Piumsomboon, P.; Chalermsinsuwan, B. Investigation of microwave-assisted regeneration of zeolite 13X for efficient direct air CO2 capture: A comparison with conventional heating method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaya, H.; Lamnini, S.; Sehaqui, H.; Jacquemin, J. Amine-Functionalized Cellulose as Promising Materials for Direct CO2 Capture: A Review. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 16380–16395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, R.; Peng, K.; Zhao, K.; Bai, M.; Li, H.; Gao, W.; Gong, Z. Amine-impregnated porous carbon–silica sheets derived from vermiculite with superior adsorption capability and cyclic stability for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Gorji, Z.E.; Singh, R.; Sharma, V.; Repo, T. Silica Gel Supported Solid Amine Sorbents for CO2 Capture. Energy Environ. Mater. 2024, 8, e12832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Okubayashi, S. Polyethyleneimine-crosslinked cellulose aerogel for combustion CO2 capture. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 225, 115248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepahvand, S.; Jonoobi, M.; Ashori, A.; Gauvin, F.; Brouwers, H.J.H.; Oksman, K.; Yu, Q. A promising process to modify cellulose nanofibers for carbon dioxide (CO2) adsorption. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 230, 115571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A.A.; Amjad, S.; Irshad, A.; Kokab, O.; Ullah, M.S.; Farid, A.; Mehmood, R.A.; Hassan, S.U.; Nazir, M.S.; Ahmed, M. From Fundamentals to Synthesis: Covalent Organic Frameworks as Promising Materials for CO2 Adsorption. Top. Curr. Chem. 2025, 383, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Xue, Q.; Li, R.; Fang, C.; Li, H.; Ding, J.; Wan, H.; Guan, G. Screening and preparation of functionalized TpBD-COFs for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 301, 120702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khdary, N.H.; Alayyar, A.S.; Alsarhan, L.M.; Alshihri, S.; Mokhtar, M. Metal Oxides as Catalyst/Supporter for CO2 Capture and Conversion, Review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomass Source | CO2 Uptake (mmol/g) | Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pistachio Shells | 2.17 | 30 °C and 1 bar | [26] |

| 3.56 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [41] | |

| Chicken Manure | 1.95 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [42] |

| Coffee Grounds | 2.67 | 35 °C and 1 bar | [43] |

| Corn Cobs | 1.52 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [27] |

| 2.81 | [44] | ||

| Chitosan | 4.82 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [29] |

| Lotus Petiole | 4.00 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [30] |

| Ginger | 4.87 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [32] |

| Tobacco Stem | 5.59 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [34] |

| 5.60 | [45] | ||

| Sugarcane Bagasse | 3.76 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [35] |

| Cellulose | 2.89 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [46] |

| Peanut Shell | 3.76 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [47] |

| Cashew Nut Shell | 11 | 25 °C and 10 bars | [48] |

| Palm Date Seeds | 4.36 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [40] |

| 5.44 | [38] | ||

| Winged Beans | 2.67 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [40] |

| Guava Seeds | 3.02 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [40] |

| Pineapple Waste | 4.25 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [49] |

| Coca Cola Waste | 5.20 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [50] |

| Coconut Shell | 3.90 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [51] |

| Olive Waste | 1.85 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [52] |

| Bamboo | 3.49 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [53] |

| Soy Beans | 3.01 | 25 °C and 1 bar | [54] |

| Sample | Precursor | Activator | T (°C) | SBET (m2/g) | Vn (cm3/g) | N % | P % | CO2 Uptake (mmol/g) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPCP-600-2 | Lotus petiole | KOH (1:2) | 600 | 861 | 0.39 | 0.71 | 3.39 | 2.57 | [30] |

| LPCP-600-3 | KOH (1:3) | 1390 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 2.07 | 4.00 | |||

| LPCP-700-2 | KOH (1:2) | 700 | 1228 | 0.54 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 3.76 | ||

| LPCP-700-3 | KOH (1:3) | 1456 | 0.71 | 1.15 | 0.30 | 3.91 | |||

| NPC | Chitosan | NaNH2 (1:1) | 600 | 1555 | 0.54 | - | - | 2.89 | [29] |

| NBPC-10 | 1553 | 0.55 | - | - | 3.14 | ||||

| PSB-PA | Pistachio shell | N2 + CO2 (50 mL/min) | 700 | 340 | 0.07 | 0.42 | - | 1.3 | [26] |

| PSB-CA | KOH (2:1) | 600 | 531 | 0.21 | 0.28 | - | 2.17 | ||

| KTC | Tobacco stems | KOH (1:2) | 700 | 1259 | 0.64 | 0.90 | - | 4.78 | [45] |

| KTC5 | 1664 | 0.83 | 0.71 | - | 5.59 | ||||

| KUTC | Tobacco stems + urea | 1936 | 0.80 | 3.05 | 3.50 | ||||

| KUTC5 | 2067 | 0.78 | 4.41 | - | 3.85 | ||||

| TS500-5T | Tobacco stems | KOH (1:2) | 500 | 638 | 0.28 | 1.89 | - | 3.56 | [34] |

| TS600-5T | 600 | 728 | 0.35 | 1.17 | - | 4.81 | |||

| TS700-5T | 700 | 1665 | 0.83 | 0.71 | - | 5.59 | |||

| TS800-5T | 800 | 1525 | 0.32 | 0.81 | - | 5.16 | |||

| K2CO3:DG-1:1-700 | Distilled spent grains | K2CO3 (1:1) | 700 | 1317 | 0.49 | - | - | 4.33 | [65] |

| K2CO3:DG-1:2-700 | K2CO3 (1:2) | 1194 | 0.44 | - | - | 5.20 | |||

| K2CO3:DG-1:3-700 | K2CO3 (1:3) | 1046 | 0.38 | - | - | 4.61 | |||

| K2CO3:DG-1:2-800 | K2CO3 (1:2) | 800 | 1591 | 0.66 | - | - | 4.21 | ||

| HAC-650-1.5 | Walnut shell powders + urea | KOH (1:1.5) | 650 | 759 | 0.33 | 4.45 | - | 2.32 | [66] |

| HAC-750-1.5 | 750 | 1636 | 0.68 | 2.69 | - | 2.86 | |||

| HAC-850-1.5 | 850 | 2354 | 0.97 | 0.86 | - | 3.04 | |||

| HAC-650-2.5 | KOH (1:2.5) | 650 | 1606 | 0.78 | 4.02 | - | 1.92 | ||

| HAC-750-2.5 | 750 | 2251 | 1.03 | 0.94 | - | 2.54 | |||

| HAC-850-2.5 | 850 | 2556 | 0.96 | 0.76 | - | 2.27 |

| Material | CO2 Adsorption Capacity | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass-Derived Carbon | ~2–6 mmol/g |

|

|

| MOFs | ~6–9 mmol/g |

|

|

| COFs | ~2–4 mmol/g |

|

|

| Zeolites | ~3–5 mmol/g |

|

|

| Amine-Based Cellulose | ~2–5 mmol/g |

|

|

| Metal Oxides | ~8–12 mmol/g |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicolae, S.A. Current Trends in Synthesis and Characterization of Biomass-Based Materials for CO2 Capture. Biomass 2025, 5, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040070

Nicolae SA. Current Trends in Synthesis and Characterization of Biomass-Based Materials for CO2 Capture. Biomass. 2025; 5(4):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040070

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicolae, Sabina Alexandra. 2025. "Current Trends in Synthesis and Characterization of Biomass-Based Materials for CO2 Capture" Biomass 5, no. 4: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040070

APA StyleNicolae, S. A. (2025). Current Trends in Synthesis and Characterization of Biomass-Based Materials for CO2 Capture. Biomass, 5(4), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040070