Biomass Demineralization and Pretreatment Strategies to Reduce Inhibitor Concentrations in Itaconic Acid Fermentation by Aspergillus terreus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pretreatment of Wheat Straw

2.2. Enzyme Buffer Exchange and Hydrolysis of Wheat Straw

2.3. Fungal Strain and Inoculum Preparation

2.4. Cultivation of A. terreus

2.5. Analytical Procedures

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fermentation of Detoxified Dilute Sulfuric Acid Pretreated Raw Wheat Straw Hydrolysate

3.2. Demineralization of Wheat Straw

3.3. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Pretreated Wheat Straw

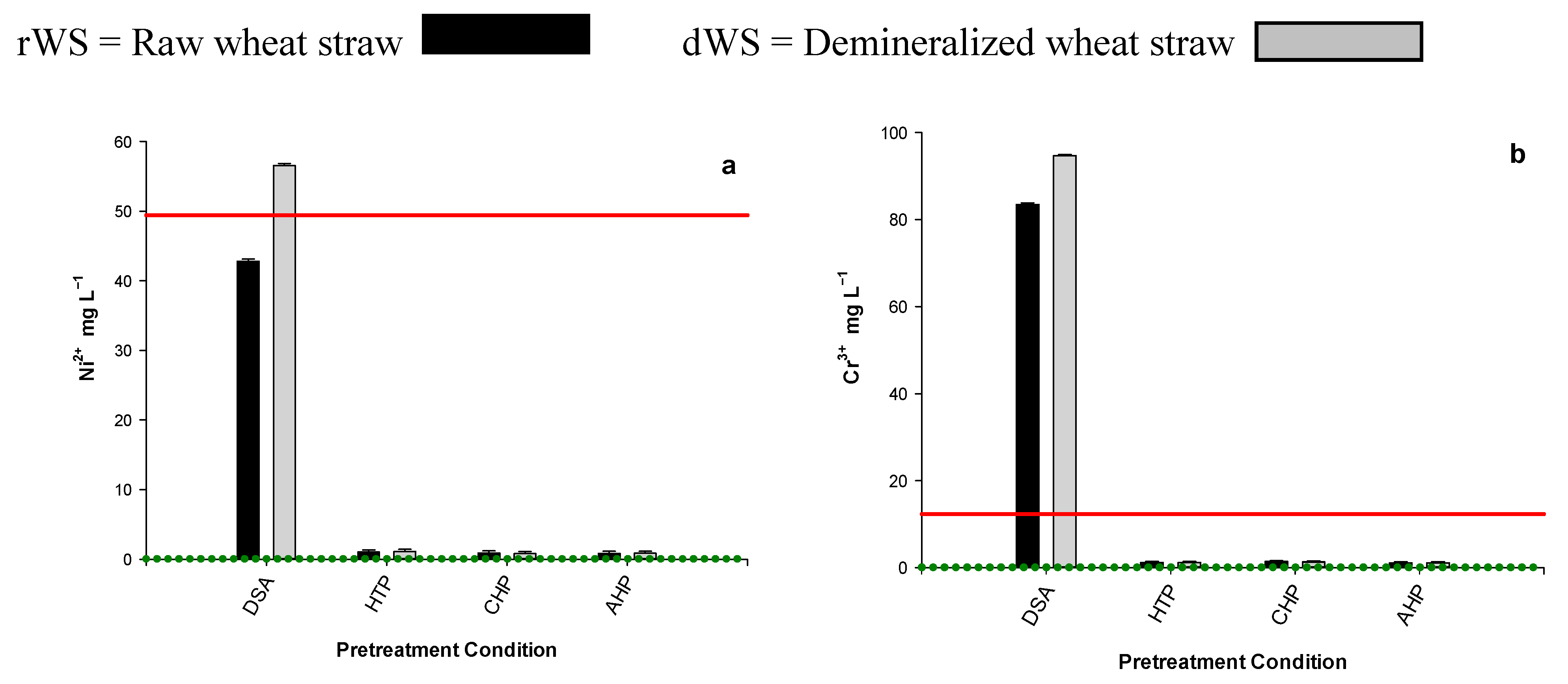

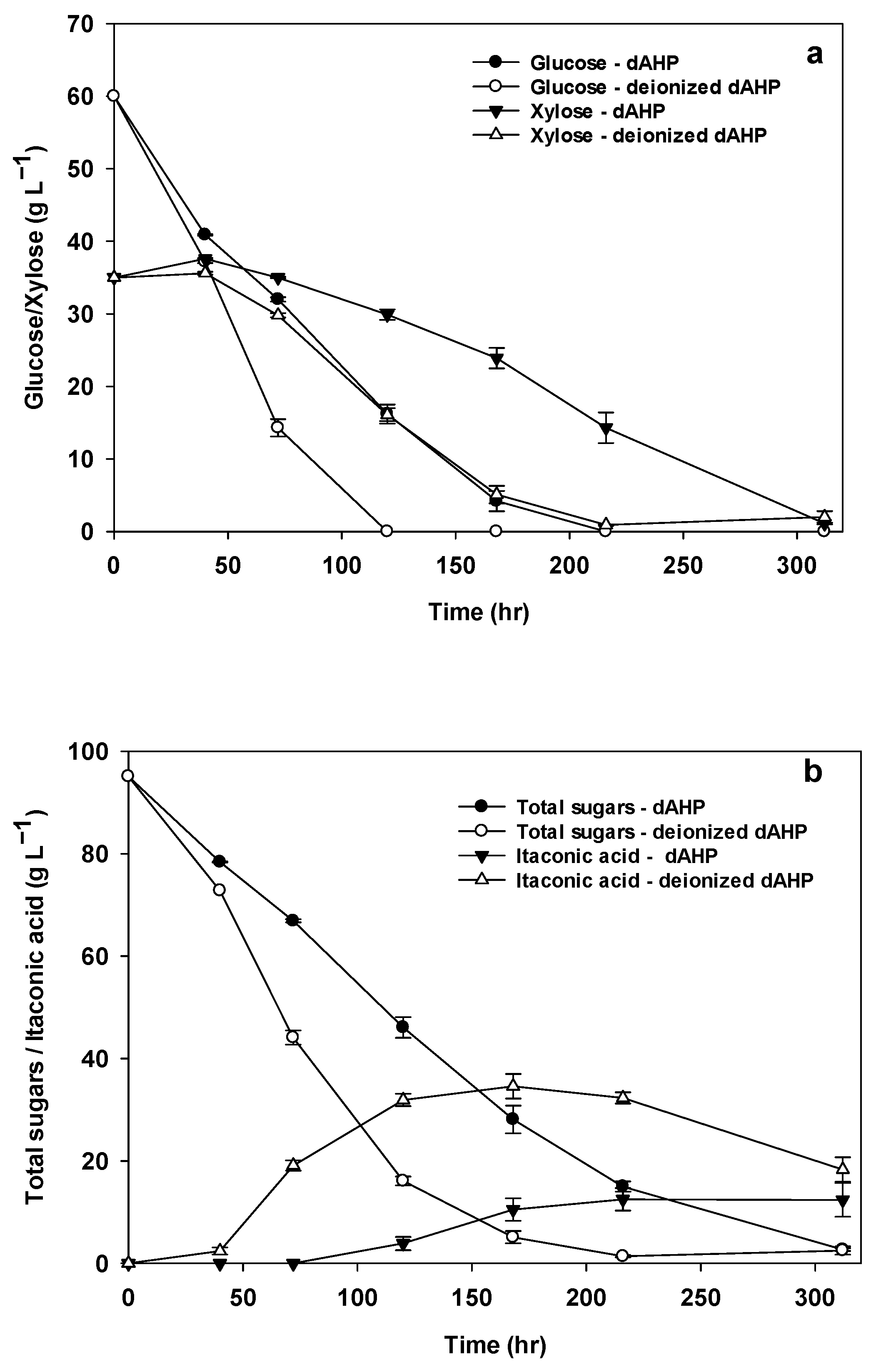

3.4. WSH Inhibitor Content

3.5. Inhibitor Dilution Bioassay

3.6. Pretreatment and Fermentation Strategies

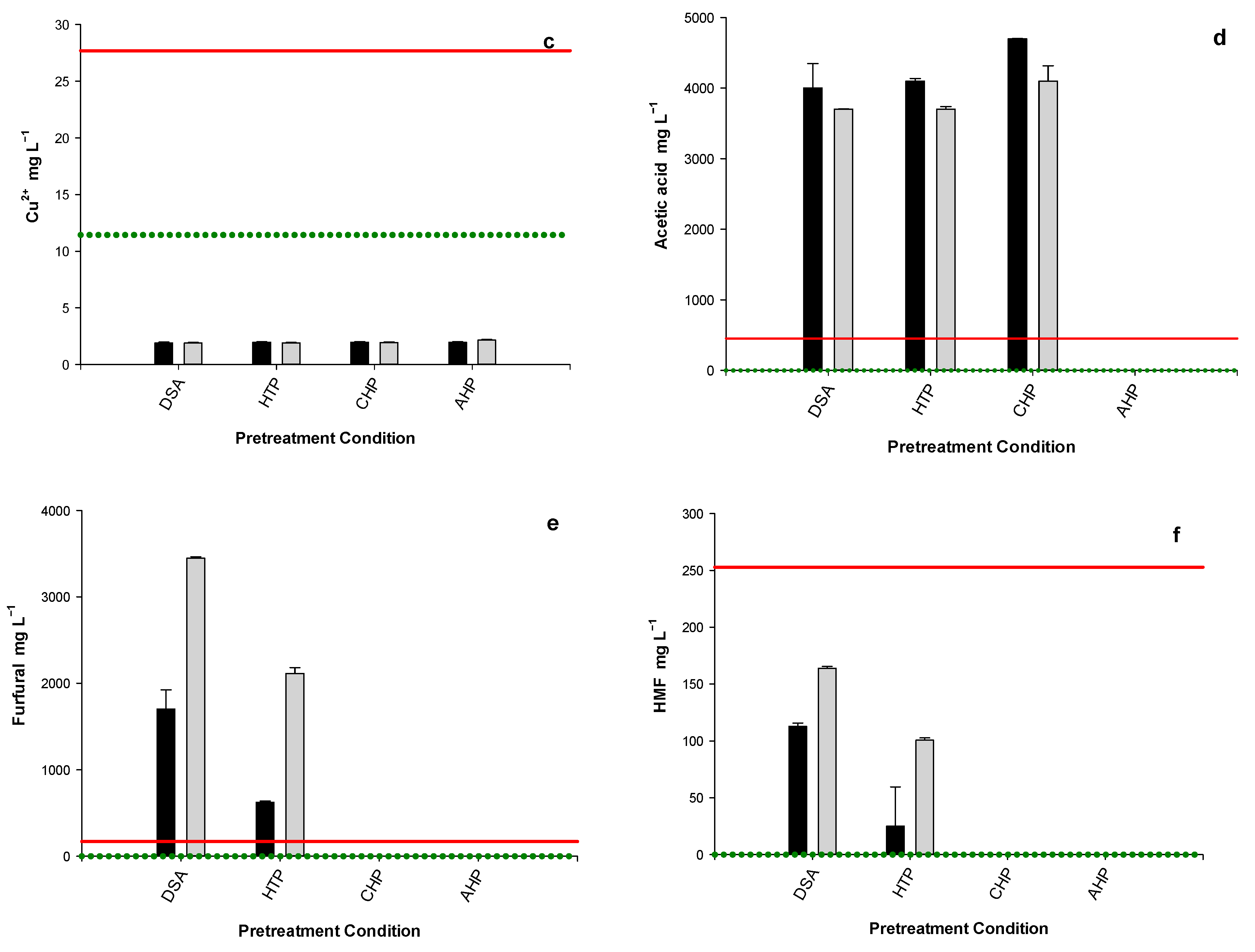

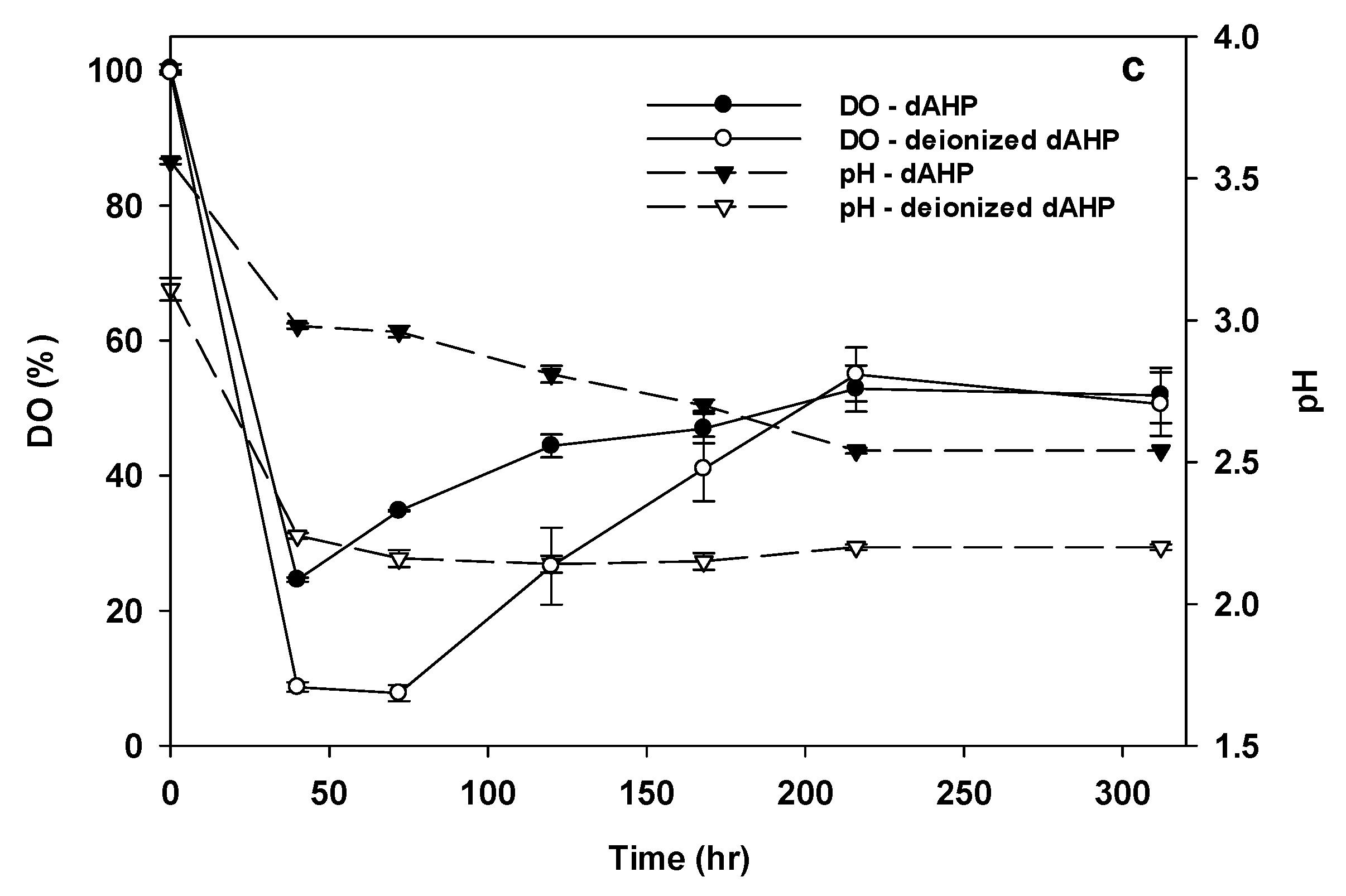

3.7. IA Production from dAHP Wheat Straw Hydrolysate

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nubel, R.C.; Ratajak, E.J. Process for Producing Itaconic Acid. U.S. Patent 3,044,941, 17 July 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Krishnan, S.; Samal, S.K.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Itaconic acid used as a versatile building block for the synthesis of renewable resource-based resins and polyesters for future prospective: A review. Polym. Int. 2017, 66, 1349–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Singh, S.; Manickam, S.; Cruz-Martins, N.; Kumar, V.; Verma, R.; Kumar, D. Itaconic Acid and Its Applications for Textile, Pharma and Agro-Industrial Purposes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleky, B.-E.; Vodnar, D.C. Biomass-derived production of itaconic acid as a building block in specialty polymers. Polymers 2019, 11, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werpy, T.; Petersen, G. Top Value Added Chemicals from Biomass: Volume I—Results of Screening for Potential Candidates from Sugars and Synthesis Gas (No. DOE/GO-102004-1992, 15008859); Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, V.; Chiaramonti, D.; Kumar, S. Review of US and EU initiatives toward development, demonstration, and commercialization of lignocellulosic biofuels. Biofpr 2013, 7, 732–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cheng, J. Hydrolysis of lignocellulosic materials for ethanol production: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 83, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, A.T.W.M.; Zeeman, G. Pretreatments to enhance the digestibility of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.C.; Kennedy, G.J. Phosphate limitation alleviates the inhibitory effect of manganese on itaconic acid production by Aspergillus terreus. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 101016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmqvist, E.; Hahn-Hägerdal, B. Fermentation of lignocellulosic hydrolysates. II: Inhibitors and mechanisms of inhibition. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 74, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaffa, L.; Diaz, R.; Papp, B.; Fekete, E.; Sandor, E.; Kubicek, C. A deficiency of manganese ions in the presence of high sugar concentrations is the critical parameter for achieving high yields of itaconic acid by Aspergillus terreus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 7937–7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, J.K.; Lasure, L.L. Organic acid production by filamentous fungi. In Advances in Fungal Biotechnology for Industry, Agriculture, and Medicine; Tkacz, J.S., Lange, L., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 307–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.C.; Kennedy, G.J.; Bowman, M.J.; Qureshi, N.; Dunn, R.O. Factors affecting production of itaconic acid from mixed sugars by Aspergillus terreus. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 187, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Roberto, I.C. Hydrolysate detoxification with activated charcoal for xylitol production by Candida guilliermondii. Biotechnol. Let. 2001, 23, 1681–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.C.; Iten, L.B.; Cotta, M.A.; Wu, Y.V. Dilute acid pretreatment, enzymatic saccharification, and fermentation of rice hulls to ethanol. Biotechnol. Prog. 2005, 21, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krull, S.; Eidt, L.; Hevekerl, A.; Kuenz, A.; Prüße, U. Itaconic acid production from wheat chaff by Aspergillus terreus. Process Biochem. 2017, 63, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Trinh, L.T.P.; Lee, H.-J. Removal of inhibitors from a hydrolysate of lignocellulosic biomass using electrodialysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 122, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. Physico-Chemical Conversion of Lignocellulose: Inhibitor Effects and Detoxification Strategies: A Mini Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieder-Heitmann, M.; Haigh, K.F.; Görgens, J.F. Process design and economic analysis of a biorefinery co-producing itaconic acid and electricity from sugarcane bagasse and trash lignocelluloses. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 262, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerssemakers, A.A.J.; Doménech, P.; Cassano, M.; Yamakawa, C.K.; Dragone, G.; Mussatto, S.I. Production of itaconic acid from cellulose pulp: Feedstock feasibility and process strategies for an efficient microbial performance. Energies 2020, 13, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, K.; Lai, C.; Ouyang, J.; Yong, Q. Improved itaconic acid production from undetoxified enzymatic hydrolysate of steam-exploded corn stover using an Aspergillus terreus mutant generated by atmospheric and room temperature plasma. Bioresources 2016, 11, 9047–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, G.B.; Montipó, S.; Mario, D.A.N.; Alves, S.H.; Martins, A.F. Building block itaconic acid from left-over biomass. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2017, 7, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippkötter, N.; Duwe, A.-M.; Wiesen, S.; Sieker, T.; Ulber, R. Enzymatic hydrolysis of beech wood lignocellulose at high solid contents and its utilization as substrate for the production of biobutanol and dicarboxylic acids. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 167, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Gu, Y.; Lv, X.; Zheng, Z.; Jiang, S.; Li, X. Production of itaconic acid by biotransformation of wheat bran hydrolysate with Aspergillus terreus CICC40205 mutant. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Xu, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, N.; Xie, J.; Zhao, J.; Bu, Q.; Wei, M. Itaconic acid production from undetoxified enzymatic hydrolysate of bamboo residues using Aspergillus terreus. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slininger, P.J.; Shea-Andersh, M.A.; Thompson, S.R.; Dien, B.S.; Kurtzman, C.P.; Balan, V.; de Costa Sousa, L.; Uppugundla, N.; Dale, B.E.; Cota, M.A. Evolved strains of Scheffersomyces stipitis achieving high ethanol productivity on acid- and base-pretreated biomass hydrolyzate at high solids loading. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dien, B.S.; Anderson, W.F.; Cheng, M.; Knoll, J.E.; Lamb, M.; O’Bryan, P.J.; Singh, V.; Sorensen, R.B.; Strickland, T.C.; Slininger, P.J. Field productivities of Napier Grass for production of sugars and ethanol. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssenkrupp, Stainless Steel 1.4435 Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.thyssenkrupp-materials.co.uk/stainless-steel-14435.html (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Xiao, Z.; Storms, R.; Tsang, A. Microplate-based filter paper assay to measure total cellulase activity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 88, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.C.; Kennedy, G.J. Ninety six well microtiter plate as microbioreactors for production of itaconic acid by six Aspergillus terreus strains. J. Microbiol. Methods 2018, 144, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.C.; Kennedy, G.J. Efficient itaconic acid production by Aspergillus terreus: Overcoming the strong inhibitory effect of manganese. Biotechnol. Prog. 2020, 36, e2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, B.M.; Bakker, R.R.; Wei, J.B. On the properties of washed straw. Biomass Bioenergy 1996, 10, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, S.; Sun, L.; Su, S.; Xu, K.; He, L.; Xiang, J. Influence of different demineralization treatments on physicochemical structure and thermal degradation of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 146, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörhammer, H.; Dou, C.; Gustafson, R.; Suko, A.; Bura, R. Removal of non-structural components from poplar whole-tree chips to enhance hydrolysis and fermentation performance. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Bao, J. De-ashing treatment of corn stover improves the efficiencies of enzymatic hydrolysis and consequent ethanol fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 169, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Hess, J.R.; Boardman, R.D.; Wright, C.T.; Westover, T.L. Formulation, pretreatment, and densification options to improve biomass specifications for co-firing high percentages with coal. Ind. Biotechnol. 2012, 8, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragsdale, S. Metal-Carbon Bonds in Enzymes and Cofactors. Coord Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 1948–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, C.; Wu, X.; Huang, Y.; Lai, C.; Li, X.; Yong, Q. Prewashing enhances the liquid hot water pretreatment efficiency of waste wheat straw with high free ash content. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 219, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-H.; Wang, Z.; Dien, B.S.; Slininger, P.J.W.; Singh, V. Economic analysis of cellulosic ethanol production from sugarcane bagasse using a sequential deacetylation, hot water and disk-refining pretreatment. Processes 2019, 7, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the chemical composition of biomass. Fuel 2010, 89, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regestein, L.; Klement, T.; Grande, P.; Kreyenschulte, D.; Heyman, B.; Maßmann, T.; Eggert, A.; Sengpiel, R.; Wang, Y.; Wierckx, N.; et al. From Beech Wood to Itaconic Acid: Case Study on Biorefinery Process Integration. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lee, D.-J. Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment by Deep Eutectic Solvents on Lignin Extraction and Saccharification Enhancement: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 339, 125587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevekerl, A.; Kuenz, A.; Vorlop, K.-D. Influence of the pH on the itaconic acid production with Aspergillus terreus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 10005–10012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kering, M.K.; Rahemi, A.; Temu, V.W. Effect of harvest management on biomass yield, forage quality, and nutrient removal by bioenergy grasses in mid-central Virginia. Agronomy 2024, 14, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Ctec2® Enzyme | Desalted Ctec2® * | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Activities (U mL−1) | ||||

| Filter paper activity (FPU) | 43.3 | 2.2 (44.4) | 2.5 | |

| Carboxymethyl cellulase | 1048 | 51 (1020) | −2.6 | |

| Xylanase | 16163 | 754 (15071) | −6.8 | |

| β-Glucosidase | 1427 | 66 (1319) | −7.5 | |

| β-Xylosidase | 22.5 | 1.04 (20.8) | −7.7 | |

| α-l-Arabinofuranosidase | 4.4 | 0.20 (4.0) | −9.2 | |

| Protein (mg L−1) | ||||

| 89.5 | 3.8 (75.1) | −16.1 | ||

| Element/Ion (mg L−1) | ||||

| Cu a | 44.8 | 2.39 (47.9) | 6.8 | |

| Ni a | 16.9 | 0.89 (17.7) | 4.6 | |

| Cr a | 21.7 | 0.99 (19.8) | −8.6 | |

| Fe a | 38.6 | 1.82 (36.4) | −5.6 | |

| S a | 3569 | 184.3 (3686.7) | 3.3 | |

| Mn a | 4.4 | 0.03 (0.5) | −88.6 | |

| Ca a | 329.2 | N.D. | −100 | |

| K a | 1592 | 3.16 (63.2) | −96 | |

| Mg a | 155.2 | N.D. | −100 | |

| P a | 1906.8 | 5.84 (116.8) | −93.9 | |

| NH4+ b | 684.8 | N.D. | −100 | |

| Cl− b | 109.1 | 0.25 (4.9) | −95.5 | |

| SO42− b | 1204.1 | 1.26 (25.1) | −97.9 | |

| PO43− b | 5863.4 | 1.63 (32.6) | −99.4 | |

| NO3− b | 30.6 | 2.32 (46.6) | 52.4 | |

| Zn a | N.D. | N.D. | - | |

| Co a | N.D. | N.D. | - | |

| Substrate | Pretreatment | Glucose (g L−1) | Xylose (g L−1) | Arabinose (g L−1) | Total Sugars (g L−1) 1 | Yield (g g−1) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rWS | DSA | 41.3 ± 0.7 | 25.0 ± 1.0 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 73.3 ± 0.4 | 0.587 ± 0.004 |

| rWS | HTP | 31.0 ± 0.3 | 20.8 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 55.0 ± 0.8 | 0.444 ± 0.007 |

| rWS | CHP | 33.5 ± 0.1 | 23.1 ± 0.0 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 60.0 ± 0.1 | 0.469 ± 0.000 |

| rWS | AHP | 26.8 ± 1.1 | 22.7 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 52.5 ± 2.4 | 0.262 ± 0.012 |

| dWS | DSA | 41.6 ± 0.1 | 20.9 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.0 | 69.3 ± 0.1 | 0.554 ± 0.001 |

| dWS | HTP | 46.4 ± 3.6 | 26.1 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 77.5 ± 5.0 | 0.620 ± 0.040 |

| dWS | CHP | 38.9 ± 1.1 | 25.7 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 68.0 ± 0.8 | 0.531 ± 0.006 |

| dWS | AHP | 39.7 ± 1.6 | 31.2 ± 1.9 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 75.1 ± 3.8 | 0.376 ± 0.019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kennedy, G.J.; Bowman, M.J.; Ascherl, K.L.; Nichols, N.N.; Saha, B.C. Biomass Demineralization and Pretreatment Strategies to Reduce Inhibitor Concentrations in Itaconic Acid Fermentation by Aspergillus terreus. Biomass 2024, 4, 1122-1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass4040062

Kennedy GJ, Bowman MJ, Ascherl KL, Nichols NN, Saha BC. Biomass Demineralization and Pretreatment Strategies to Reduce Inhibitor Concentrations in Itaconic Acid Fermentation by Aspergillus terreus. Biomass. 2024; 4(4):1122-1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass4040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleKennedy, Gregory J., Michael J. Bowman, Kim L. Ascherl, Nancy N. Nichols, and Badal C. Saha. 2024. "Biomass Demineralization and Pretreatment Strategies to Reduce Inhibitor Concentrations in Itaconic Acid Fermentation by Aspergillus terreus" Biomass 4, no. 4: 1122-1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass4040062

APA StyleKennedy, G. J., Bowman, M. J., Ascherl, K. L., Nichols, N. N., & Saha, B. C. (2024). Biomass Demineralization and Pretreatment Strategies to Reduce Inhibitor Concentrations in Itaconic Acid Fermentation by Aspergillus terreus. Biomass, 4(4), 1122-1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass4040062