1. Introduction

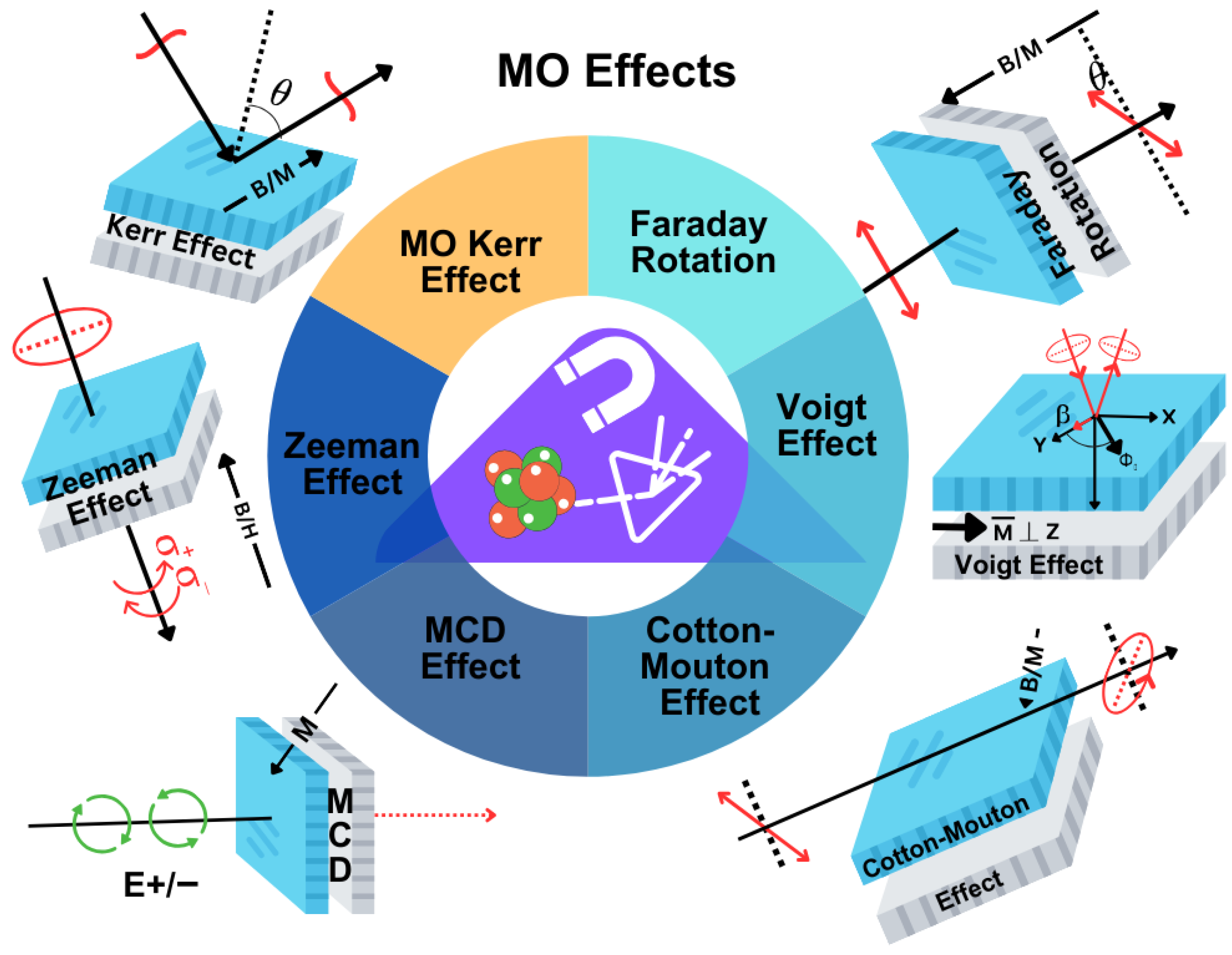

Magnetooptics (MO) explores the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and magnetized media, providing critical insights into spin dynamics, optical manipulation, and quantum behavior in materials [

1,

2]. The pioneering contributions of Michael Faraday [

3] and John Kerr [

4] in the 19th century revealed how magnetic fields could alter the polarization and reflection properties of light, phenomena that now underpin key applications such as optical isolators [

5,

6], high-precision sensors [

7], and magnetooptical data storage systems [

8], to name a few.

James Clerk Maxwell’s unification of electromagnetic theory further formalized the underlying principles [

9,

10], setting the stage for the modern evolution of magnetooptical technologies. Today, MO effects serve as indispensable tools in diverse fields, including spintronics [

11,

12,

13], optical communication [

14,

15], data storage [

8,

16], quantum computing [

17], and nanophotonics [

18], among many others.

Technological breakthroughs in ultrafast laser systems [

19,

20,

21], material engineering [

6,

22,

23], and nanofabrication [

24] have propelled MO research into femtosecond and nanoscale domains [

25]. Advanced characterization techniques [

26,

27] such as the time-resolved magnetooptical Kerr effect (TR-MOKE) [

28], magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) [

29], and Kerr microscopy [

27] now enable real-time imaging [

30] of magnetic domain structures and spin dynamics [

19,

20] at ultrafast timescales [

31].

Simultaneously, the integration of MO effects with plasmonic structures has led to the emergence of magnetoplasmonics [

32,

33]. These hybrid platforms leverage both magnetic and optical resonances to significantly increase sensitivity, spatial resolution, and functional diversity for applications such as environmental monitoring, biosensing, and optical modulation, among others [

7,

34]. The rise of all-dielectric magnetooptical metasurfaces presents a promising alternative to metallic architectures by minimizing optical losses while preserving strong MO coupling [

35,

36,

37]. In addition, computational approaches driven by artificial intelligence (AI) are increasingly being used to model, design, and optimize complex MO devices [

38,

39,

40,

41].

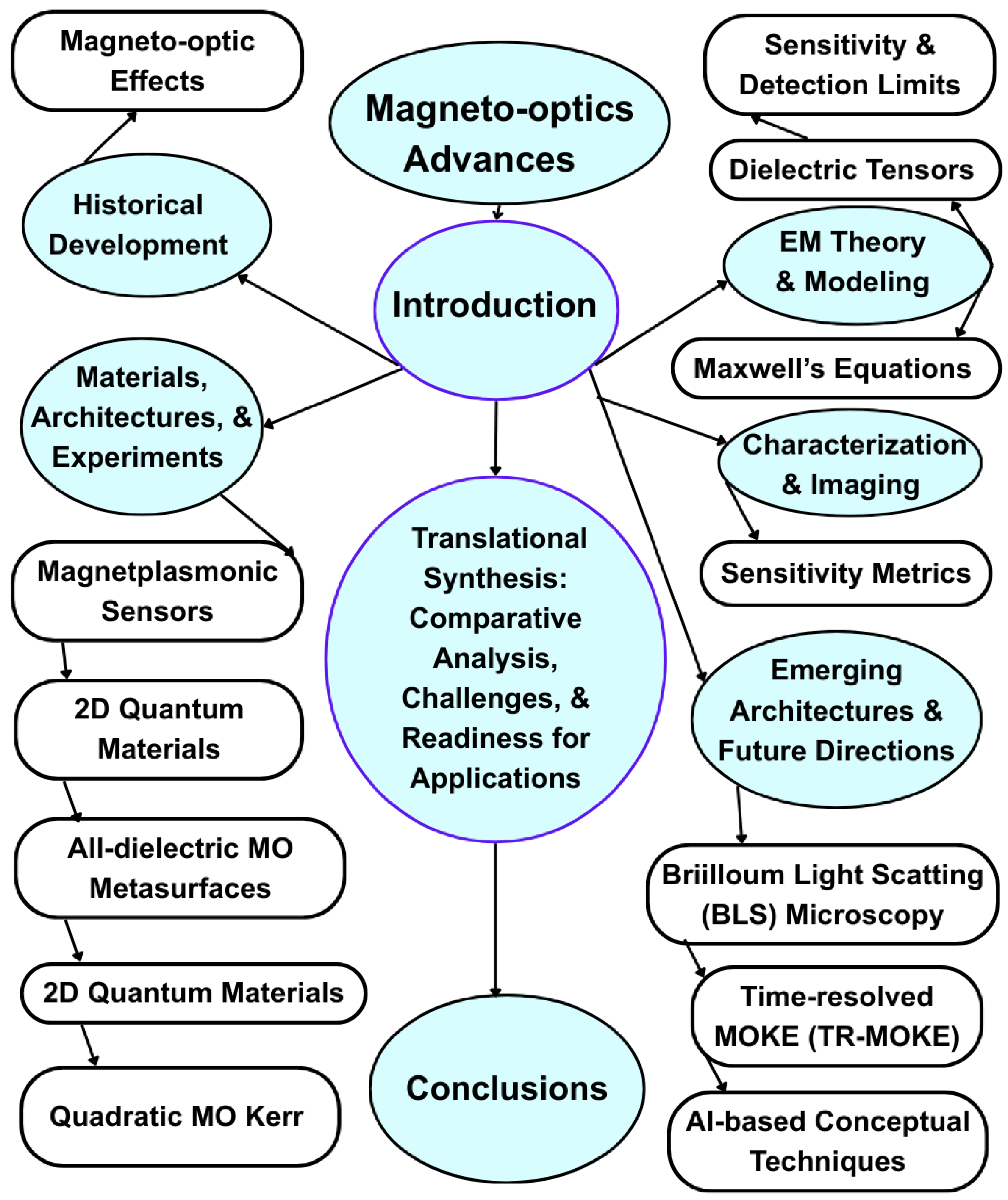

Figure 1 shows a unified conceptual framework of MO and advances in magnetoplasmonics (MP), capturing the organization and interconnections of the review. The diagram begins with the Introduction, which sets the stage for discussions on the foundational aspects of the field. From this starting point, the framework branches into multiple themes that collectively define the scope of current research.

The development of MO is presented alongside the core understanding of MO effects, both of which provide context for subsequent innovations. Building on these foundations, the discussion extends into materials, architectures, and experiments, encompassing advances in MP sensors, 2D quantum materials, all-dielectric MO metasurfaces, and quadratic MO Kerr effects.

These emerging material platforms highlight the expansion of magnetooptical phenomena into new domains of nanoscale engineering [

42,

43]. Recent studies, including the work of Gabbani et al. on doped transparent conductive oxide (TCO) nanocrystals, further demonstrate that carefully engineered nanoparticles can surpass the magnetoplasmonic performance of conventional noble metals by nearly an order of magnitude [

44,

45].

Building on these advances, current research increasingly emphasizes novel device architectures and emerging application frontiers. These efforts encompass next-generation photonic platforms, multifunctional sensing paradigms, and spintronic integrations that collectively expand the translational potential of magnetooptical systems [

34].

Central to this progression is the integrative framework of Translational Synthesis: Comparative Analysis, Challenges, and Readiness for Applications (see

Section 7). This framework systematically evaluates performance trade-offs, identifies key barriers, including thermal stability, fabrication complexity, and reproducibility, and assesses the technological maturity required for real-world deployment. In doing so, this review bridges the gap between fundamental discoveries and application-ready solutions, culminating in perspectives that consolidate current insights and highlight emerging opportunities.

3. Electromagnetic Theory and Modeling

Electromagnetic theory provides the fundamental framework for understanding the interaction of light with magnetized materials [

46,

127,

128]. At its core, plasmonics investigates how electromagnetic waves couple with free electrons in metals, leading to collective oscillations known as surface plasmons [

129]. When confined to metal—dielectric interfaces, these excitations, referred to as surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs), exhibit strong sensitivity to changes in the surrounding dielectric environment. This property underpins a wide range of applications, spanning optical sensing, nanophotonics, energy-harvesting technologies, and beyond.

The phenomenon of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) arises when incident p-polarized light excites surface plasmons under specific resonance conditions, resulting in a characteristic dip in reflected intensity [

119]. Such resonances, which are highly tunable by material and structural design, enable a wide range of applications, ranging from label-free biosensing and environmental monitoring to other sensing and photonic technologies [

34,

130].

Plasmon excitation also leads to pronounced field localization and enhancement, particularly in nanostructures or sharp metallic features [

130]. These “hot spots” can amplify local electromagnetic fields by several orders of magnitude relative to the incident field, enabling phenomena such as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) and single-molecule detection [

131].

The integration of magnetooptical activity with plasmonics introduces an additional degree of freedom: external magnetic fields can modulate the dielectric tensor of a material, thereby tuning resonance conditions [

101]. This magnetooptical modulation of SPR allows dynamic control of spectral properties, including the resonance angle, linewidth, and intensity, paving the way for advanced optical switches, modulators, and active sensing devices [

132].

As discussed by Kittel and Yeh, the theoretical description of these interactions is rooted in Maxwell’s equations, augmented by appropriate constitutive relations to account for anisotropic, symmetry-dependent, and non-reciprocal material responses governing electromagnetic wave propagation in solids and layered media [

133,

134]. In magnetooptical systems, the dielectric

becomes a tensor with off-diagonal elements that are directly linked to the magnetization. Linear magnetooptical effects, such as the Faraday and Kerr rotations, originate from these off-diagonal components and scale with the magnetization vector [

1].

Higher-order effects, on the other hand, emerge from quadratic or more complex dependencies, introducing additional anisotropy and enhancing the sensitivity of detection techniques. To accurately model both linear and nonlinear responses, the full dielectric tensor, including its magnetic-field-dependent components, must be considered [

135].

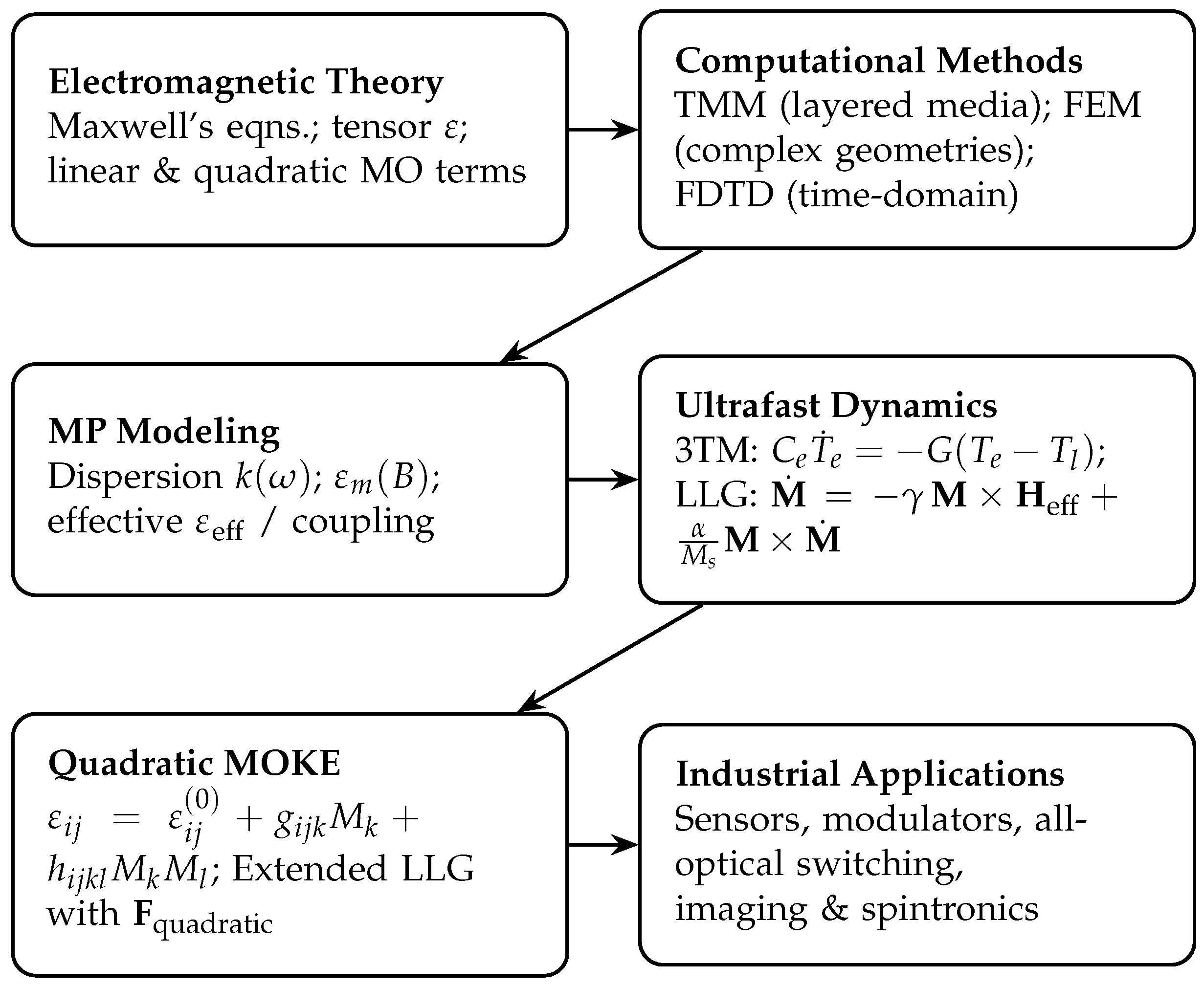

Several computational approaches have been developed to solve Maxwell’s equations under realistic material and boundary conditions [

46,

128,

136,

137]. The transfer matrix method (TMM) offers efficient analytical solutions for layered planar structures, while the finite element method (FEM) and finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) techniques provide versatile frameworks for simulating arbitrarily complex geometries and time-resolved dynamics.

These numerical methods are essential for predicting optical spectra, field distributions, and magnetooptical responses in nanostructured systems. They also guide experimental design by enabling the optimization of multilayer architectures, resonance conditions, and sensing performance before fabrication.

Figure 4 illustrates the conceptual framework, starting from electromagnetic theory and advancing through computational solvers, magnetoplasmonic modeling, and ultrafast spin dynamics (3TM/LLG), before extending to quadratic nonlinear MOKE and ultimately culminating in practical applications.

Having outlined the modeling framework, we now turn to the fundamental principles of plasmonics, which form the physical basis for many magnetoplasmonic phenomena. Plasmonics investigates the interaction between electromagnetic waves and free electrons in conductive materials, typically metals [

129]. At optical frequencies, this interaction gives rise to surface plasmons, coherent oscillations of conduction electrons coupled to electromagnetic fields at metal-dielectric interfaces. These plasmonic modes are highly sensitive to changes in the local dielectric environment, making them foundational to optical sensing, nanophotonics, and photothermal applications [

18].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) in a single metal-dielectric interface occurs when incident p-polarized light at a specific angle excites surface plasmons at that interface, leading to a characteristic dip in the reflected light intensity [

119]. The resonance condition is achieved when the in-plane wavevector,

of incident light matches that of the surface plasmon mode, which depends on the angular frequency (

), the speed of light (

c), and the dielectric constants of the metal (

) and dielectric (

), as shown in Equation (

4):

where

represents the magnetically tuned dielectric constant of the metal. Such modulation forms the basis of magnetooptical sensors and switchable photonic devices.

This momentum-matching condition is highly sensitive to changes in the refractive index near the interface, enabling precise detection of molecular binding events. Due to this sensitivity, SPR has become a powerful and widely used technique for label-free biosensing, environmental monitoring, and real-time molecular interaction studies [

119].

In contrast, multilayer SPR involves a stack of alternating metal (

) and dielectric (

) layers, where the plasmonic mode results from the hybridization of multiple metal—dielectric interfaces. The dispersion relation of these coupled surface modes, represented by the in-plane wavevector

, is obtained by solving Maxwell’s boundary conditions across all layers using the transfer-matrix method [

138]. This leads to more complex field distributions

and

, allowing for tunable mode coupling. Consequently, while single-layer SPR supports a single interface-bound mode

, multilayer SPR enables mode splitting and enhanced field confinement through interference and coupling between adjacent plasmonic interfaces.

Although conventional plasmonic systems rely solely on material and structural properties to define their optical response, the introduction of an external magnetic field adds an additional degree of freedom, enabling active control over plasmonic behavior. In magnetoplasmonic systems, the application of an external magnetic field modulates the plasmonic resonance by altering the dielectric tensor of the material [

37]. This tunability introduces anisotropy and enables active control of SPR characteristics, such as the resonance angle and linewidth [

66,

132].

Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) arises from the collective oscillation of conduction electrons confined to metallic nanostructures, such as nanoparticles, tips, or sharp edges [

129,

139,

140,

141]. Plasmon excitation leads to intense local electromagnetic field enhancement near the metal surface, producing nanoscale “hot spots.” The enhancement factor

F is defined as

where

is the peak local electric field amplitude, and

is the incident field amplitude. These localized enhancements underpin phenomena such as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), enabling single-molecule detection and ultrasensitive optical sensing [

131].

Although magnetic fields can externally tune plasmonic resonances, an even more powerful approach arises from the intrinsic coupling between magnetic and plasmonic excitations, which gives rise to hybridized modes with enhanced tunability. The interaction between magnetic excitations and plasmonic modes produces hybrid resonances characterized by dynamically tunable optical responses. This coupling can be described through an effective permittivity formulation, as discussed in

Section 4, Equation (

17). Such interactions enable active control of resonance conditions, making hybrid magnetoplasmonic structures ideal for applications in active sensing, optical modulation, and integrated photonic systems [

80,

117,

142,

143].

To accurately capture and predict the complex behavior of hybrid magneto—plasmonic systems, it is essential to employ rigorous electromagnetic modeling based on Maxwell’s equations [

133]. Such modeling requires a detailed treatment of light—matter interactions under the influence of external magnetic fields. These interactions, governed by Maxwell’s equations, are described through the dielectric tensor

, which becomes anisotropic and non-reciprocal in the presence of magnetization. The general form of this tensor can be expressed as:

where the diagonal terms (

) represent the intrinsic permittivity along the principal axes, while the off-diagonal terms (

) describe the magnetooptical coupling induced by the magnetization vector

. These off-diagonal components are typically antisymmetric (

) and proportional to the components of

, i.e.,

where

Q is the magneto–optical Voigt constant and

is the Levi-Civita symbol. This formulation captures magnetooptical phenomena such as polarization rotation, circular birefringence, and non-reciprocal light propagation in magnetoplasmonic media [

101].

Numerical simulations that incorporate the full magnetooptical dielectric tensor are essential for accurately predicting both the MO spectra (e.g., Kerr rotation and ellipticity) and the corresponding electromagnetic field distributions in complex nanoscale systems. These simulations, commonly implemented using finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) or finite element method (FEM) solvers, enable quantitatively reliable analysis of multilayers, metasurfaces, and resonant nano-architectures, where analytical or effective-medium approximations fail.

As summarized in

Table 5, such modeling approaches play a critical role in optimizing sensor designs, interpreting experimental measurements, and guiding the development of new MO-active materials. Readers seeking a broader theoretical context and modeling framework are refereed to the magnetooptics Roadmap ([

43], pp. 9–10) by de Sousa and García-Martín, where electromagnetic theory and numerical simulation methodologies for MO systems are discussed in detail.

Accurate modeling also relies on computational methods capable of solving Maxwell’s equations under realistic boundary conditions. The Transfer Matrix Method (TMM) provides analytical solutions for layered media, making it well suited for planar multilayer structures. The Finite Element Method (FEM) offers high spatial accuracy for complex geometries by discretizing the system into meshes, while the Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) method simulates time-resolved electromagnetic fields in arbitrary nanostructures. These numerical tools are indispensable for predicting optical spectra, field distributions, and magnetooptical responses in device-scale architectures.

Beyond steady-state optical responses, modeling ultrafast magnetization dynamics is essential for understanding femtosecond spin—electron—lattice interactions. One widely used framework is the Three-Temperature Model (3TM) [

144], which captures nonequilibrium energy transfer among three coupled subsystems: electrons, lattice, and phonons. The electron temperature

evolves as:

where

is the electron heat capacity and

G is the electron—lattice coupling constant. The lattice temperature

and the phonon temperature

follow:

where

and

are the heat capacities of the lattice and the phonons, and

is the relaxation time. This framework explains ultrafast demagnetization and recovery driven by femtosecond laser pulses. To capture vector magnetization dynamics, the Landau—Lifshitz—Gilbert (LLG) equation is employed [

145]:

where

is the gyromagnetic ratio,

is the Gilbert damping coefficient,

is the saturation magnetization, and

is the effective magnetic field. The first term describes the precession of

around

, while the second term accounts for damping, driving the system toward equilibrium.

As presented in Equation (

10), the Landau—Lifshitz—Gilbert equation (LLG) is widely used to model the dynamics of magnetization under the influence of external magnetic fields and ultrafast excitations [

145]. This phenomenological framework describes both the precessional motion and the damping behavior of the magnetization vector

in response to the effective magnetic field

. These interactions arise from second-order contributions to the dielectric tensor and are expressed as:

where

is the total permittivity tensor that describes the optical response of the material.

is the permittivity tensor of the material in the absence of magnetization (i.e., the dielectric constant).

is the first-order magnetooptical coefficient (a third-rank tensor), responsible for linear effects such as Faraday and Kerr rotation.

is the second-order magnetooptical coefficient (a fourth-rank tensor) that accounts for quadratic coupling to magnetization.

, are components of the magnetization vector . The term thus represents the quadratic magnetooptical coupling.

Incorporating this quadratic permittivity into a dynamical model introduces an additional torque in the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation (LLG) [

145]:

where

is the macroscopic magnetization vector.

is the gyromagnetic ratio.

is the effective magnetic field, which may include contributions from external, anisotropy, and exchange fields.

is the Gilbert damping parameter.

is the saturation magnetization.

is the optically induced quadratic torque arising from the second-order term in permittivity.

This torque represents second-order optical driving forces that can trigger ultrafast magnetization switching and strong nonlinear magnetic responses. These quadratic contributions are fundamental mechanisms for all-optical magnetic switching and coherent control of spin states, offering promising pathways for the development of next-generation ultrafast spintronic memory and logic devices.

Although theoretical models such as 3TM provide valuable insights into the underlying spin—electron—lattice interactions, experimental validation is crucial for revealing their physical manifestations. Consequently, a range of experimental techniques has been developed to observe and quantify higher-order MO effects [

105,

135,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151]. Quadratic MOKE, for example, is designed to be sensitive to the

components of magnetization and has been applied effectively to antiferromagnetic (AFM) and ferrimagnetic materials.

Table 6 provides a comparative summary of linear and quadratic magnetooptical (MO) effects, emphasizing their respective dependencies on magnetization, typical material classes, detection sensitivity, and spectroscopic characterization methods.

Theoretical modeling is crucial for quantitatively interpreting the observed magnetooptical responses. In Kerr microscopy, the modeling framework is derived from Maxwell’s equations in media with magnetooptical activity. In such materials, the propagation of electromagnetic waves is described by the vector wave equation, which incorporates the magnetization-dependent permittivity tensor [

1,

127,

152]:

where

is the electric—field vector,

is the magnetization-dependent dielectric tensor and

c is the speed of light in vacuum [

1,

147].

For a linear magneto—optical response (first order in

), the dielectric tensor can be written [

1,

127,

147,

152]

or, in matrix form,

where

denotes the isotropic background permittivity,

g is the magneto—optical (gyration) coefficient,

is the Kronecker delta,

is the Levi—Civita symbol (a fully antisymmetric tensor encoding the handedness of the coordinate system), and

are the components of the magnetization vector

. The off—diagonal terms of the permittivity tensor arise from this coupling between light and magnetization and are responsible for the observed Kerr and Faraday rotations [

147].

To solve Equation (

13) for realistic nanostructured materials, numerical simulation approaches such as the finite—difference time domain (FDTD) method and the finite element method (FEM) are commonly used [

128,

153]. These computational models provide predictive insight into the spatial and spectral distribution of the magnetooptical Kerr effect (MOKE) signals, supporting both the design and interpretation of experimental observations.

Beyond structural and optical modeling, the magnetooptical Kerr effect also serves as a powerful probe of spin-dependent phenomena, providing direct insight into the dynamic behavior of magnetization and spin—orbit interactions in magnetic materials. The magnetooptical Kerr effect (MOKE) is a powerful and widely used technique for investigating spin dynamics in magnetic materials, particularly in thin films and nanostructured systems [

4,

146,

147].

When linearly polarized light reflects off a magnetized surface, interactions with spin-polarized electrons result in a modification of the polarization state of the reflected beam. This magnetization-dependent optical response gives rise to two measurable quantities: Kerr rotation (

), which corresponds to the rotation of the plane of polarization, and Kerr ellipticity (

), which quantifies the induced ellipticity of the reflected light [

116,

148,

149]. These observables are intrinsically linked to the complex dielectric tensor of the material, especially the off-diagonal component

, which encapsulates the optical anisotropy arising from magnetization and spin—orbit coupling. The complex Kerr angle is given by:

where

and

represent the diagonal elements of the

tensor along the in-plane and out-of-plane directions, respectively, and

is responsible for magnetooptically induced birefringence and dichroism [

154,

155].

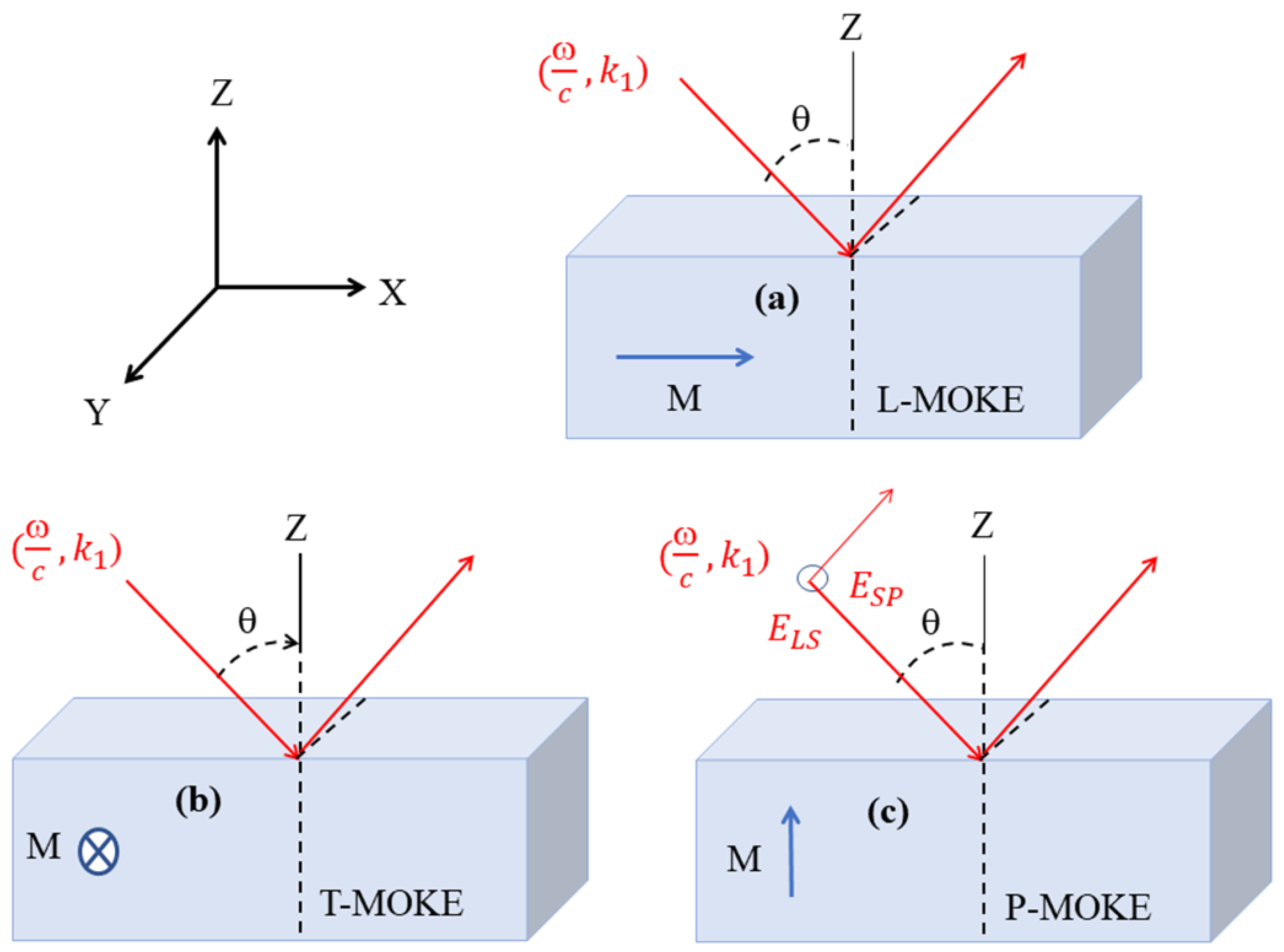

The interaction of polarized light with the spin-dependent electronic band structure leads to polarization-dependent reflection coefficients, making MOKE particularly sensitive to magnetization orientation and magnitude. By analyzing

and

, researchers can monitor real-time magnetic switching, domain wall motion, and ultrafast spin reorientation processes [

115,

150,

156]. Furthermore, the use of different MOKE geometries: longitudinal, transverse, and polar-allows selective sensitivity to magnetization components both in-plane and out-of-plane, reinforcing the status of MOKE as an indispensable tool in spintronics, magnetooptics, and ultrafast magnetism research [

12,

13,

157].

To further complement these techniques, more sophisticated magnetooptical methods have been developed to probe complex dielectric responses and ultrafast spin dynamics. magnetooptical ellipsometry provides full complex

tensor measurements and is capable of resolving subtle non-linear contributions that cannot be captured by traditional MOKE setups [

103,

158]. Nonlinear optical spectroscopy, particularly when employing ultrafast femtosecond laser pulses, enables the excitation and detection of magnetization dynamics beyond the linear regime. These methods have proven effective for probing spin reorientation transitions, magnetic phase boundaries, and the interplay between spin, charge, and lattice degrees of freedom in correlated systems.

4. Materials, Architectures, and Experimental Platforms

A wide range of materials, architectures, and experimental platforms forms the foundation of modern magnetooptical research. Among these, magnetooptics provides a unique tool for probing quantum materials, a class of substances with exotic electronic, magnetic, and optical properties [

159]. These materials, which include topological insulators, Weyl semimetals, and quantum spin liquids, are distinguished by their non-trivial band structures and the intricate interplay of spin-orbit coupling and electronic correlations [

160,

161,

162]. By leveraging the interaction between light and magnetic properties, magnetooptics enables researchers to probe the fundamental physics of these systems and explore their potential for next-generation technologies.

The same magnetooptical phenomena that provide deep insights into the physics of quantum materials are now being harnessed in applied contexts to engineer advanced photonic architectures. By translating fundamental principles of light—matter—spin interaction into functional device platforms, researchers have driven rapid progress in magnetoplasmonic and magnetophotonic sensor technologies, where the strategic combination of optical and magnetic components enables enhanced sensitivity, tunability, and multifunctionality.

Realizing these advances in practice requires careful material selection and structural engineering. In particular, the performance of magnetoplasmonic and magnetophotonic devices is strongly influenced by the choice and integration of plasmonic metals, ferromagnetic layers, and dielectric components that together determine the strength and tunability of optical and magnetooptical responses. Gold (Au) is widely used due to its chemical stability and efficient surface plasmon resonance (SPR) characteristics, whereas silver (Ag) offers superior field confinement but is limited by its susceptibility to oxidation and reduced durability. Ferromagnetic materials such as cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), and iron (Fe) are commonly incorporated to induce MO activity, particularly in Kerr and Faraday configurations.

To mitigate optical losses associated with metallic layers, modern sensor architectures integrate dielectric materials such as SiO

2 and Si

3N

4, as well as high-index dielectrics, to support Mie-type resonances in all-dielectric magnetooptical metasurfaces (ADMOMSs) [

35,

37]. These dielectric components improve light transmission, broaden spectral tunability, and enhance overall sensor stability. Furthermore, for enhanced chemical and biological selectivity, functional polymer layers, such as Nafion (for humidity detection) and Pb-phthalocyanine (for NO

2 detection), are often applied to the sensor surface. The key materials employed in magnetoplasmonic sensor architectures, along with their functional roles, are summarized in

Table 7.

The performance of magnetoplasmonic platforms is strongly affected by the intrinsic magneton damping (Gilbert) of the magnetic constituent. High damping in common ferromagnets such as Ni, Fe, and Co accelerates magnetization relaxation, broadens magneto—optical (MO) resonance linewidths, reduces coherence, and, thereby, degrades the signal-to-noise ratio and sensing stability. Consequently, there is a clear motivation to identify and integrate magnetic media with low damping constants, as reduced damping improves the quality factor of spin dynamics and sharpens MO spectra, which can translate into higher phase and intensity sensitivity in plasmon-enhanced transduction [

145].

Ongoing research explores several material families that balance low damping with optical and nanofabrication compatibility: ferrimagnetic oxides (e.g., YIG) exhibiting ultra-low damping (down to

) yet requiring epitaxial growth and careful integration with noble metals; metallic ferromagnet alloys (e.g., CoFe, FeCoB) that offer damping lower than pure 3

d ferromagnets, with CMOS-process compatibility but introduce additional optical loss; and emerging organic ferrimagnets such as V[TCNE]

x that display low-loss spin dynamics in thin films while posing challenges in long-term chemical stability and heterogeneous integration [

164].

Table 8 summarizes these classes, outlining representative examples along with the advantages and known limitations relevant to the engineering of magnetoplasmonic devices.

Transparent conductive oxides (TCOs), including ZnO, indium tin oxide (ITO), and copper chalcogenides such as

Se, are attracting growing attention as alternatives to conventional noble metals for magnetoplasmonic architectures [

45]. Their tunable carrier density over a broad spectral range, combined with the ability to support localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs), provides a versatile means of enhancing magnetooptical modulation. Recent studies have shown that co-doping TCOs with paramagnetic ions can further tailor both carrier concentration and magnetic response, thereby enabling hybrid material platforms with enhanced functionality. Importantly, Gabbani et al. [

45] demonstrated that the magnetoplasmonic response of doped TCO nanocrystals can surpass that of conventional Ag or Au nanostructures by nearly an order of magnitude, underscoring their potential to reshape the materials landscape in this field. While stability, reproducibility, and integration challenges remain, TCOs represent a highly promising class of materials that could significantly broaden the design space for next-generation magnetoplasmonic devices.

The presence of an external magnetic field,

, applied via a circular magnet surrounding the sample, induces a magnetooptic response by modulating the plasmonic dispersion relation. This

-dependent modulation enables real-time detection of

changes due to analyte interaction, improving the sensor sensitivity to gasses, humidity, or biological media. The resonance condition for surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is determined by the relation given in Equation (

4) [

129].

Recent advances in magnetoplasmonic sensing have highlighted the importance of accurately modeling the effective permittivity (

) to describe the intricate coupling between surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs), localized surface plasmons (LSPs), and magnetooptical effects such as Kerr rotation [

4,

138,

165]. To capture this coupling in a simplified form, effective permittivity

can be phenomenologically expressed as follows:

where

is the magnetization of the magnetic medium,

is the externally applied magnetic field,

represents the background (non-magnetic) permittivity, and

denotes the intrinsic dielectric constant of the plasmonic material. This simplified expression does not constitute a rigorous microscopic derivation; instead, it serves as a phenomenological model to illustrate how variations in magnetization and magnetic field strength influence the effective dielectric response of the hybrid system. It emphasizes the

field- and

-dependent tunability of magnetoplasmonic interactions, which is key to optimizing device sensitivity and performance in advanced sensing architectures.

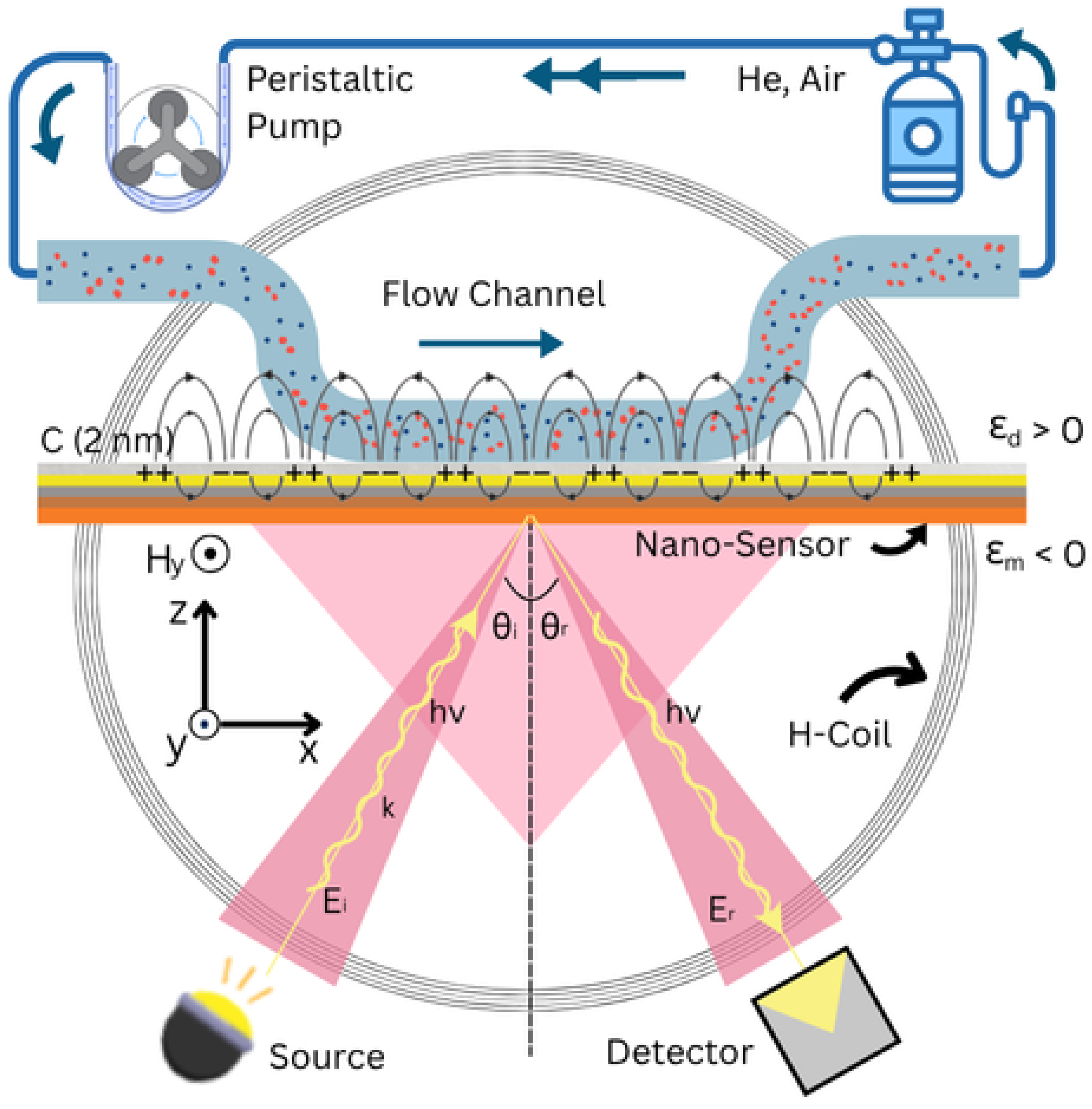

Figure 5 shows a typical experimental setup based on the Kretschmann configuration, which is used to characterize and measure the probing sample [

42]. The system integrates a peristaltic pump, an electromagnetic coil, and an angle-resolved detection unit. In this setup, a laser beam is directed through a refractive index, n, of the BK-7 prism to achieve total internal reflection at the metal-dielectric interface, generating evanescent waves that excite surface plasmons [

119]. A thin metal layer (e.g., Au or Ag) is coated with magnetic and dielectric films that support the SPR condition.

7. Translational Synthesis: Comparative Analysis, Challenges, and Readiness for Applications

Magnetooptical (MO) and magnetoplasmonic platforms have advanced significantly in recent years, driven by developments in materials engineering, multilayer architectures, and nanoscale light—matter coupling. These advances have enabled unprecedented sensitivity in biochemical sensing, environmental monitoring, and spin—photon control. However, translating laboratory demonstrations into functional technologies requires an integrated assessment of material constraints, fabrication scalability, device robustness, and system-level compatibility.

This section synthesizes comparative performance across magneto-photonic architectures, evaluates persistent cross-cutting challenges, and identifies pathways toward technological readiness. The overarching trends align with the perspectives discussed in recent reviews on emerging magnetooptical architectures and translational trajectories [

32,

43,

117] and are consistent with the broader evolution of magnetooptics summarized in [

2,

18,

34] and the comprehensive survey in Ref. [

83].

7.1. Comparative Performance Across MO-Enhanced Sensing Platforms

Magnetoplasmonic sensors based on Kretschmann configurations integrating Au/Co, Au/Co/Ag, or periodic Co/Au stacks demonstrate a clear enhancement of transverse magnetooptical Kerr effect (T-MOKE) signals due to the strong overlap between plasmonic near-fields and magnetic layers [

66,

117].

As summarized in

Table 16, magnetophotonic platforms leveraging hybrid SPP—LSP excitation achieved attomole analytical sensitivity [

18], whereas multilayer Au/Co/polyimide stacks targeted gas-phase analytes and delivered improvements of an order of magnitude beyond conventional SPR [

34]. These systems differ in theoretical treatment and optimization strategies: the former employs propagation constant analysis for mode coupling, while the latter uses T-MOKE and multi-thickness tuning to engineer depth-dependent field enhancement. Rizal et al. demonstrate attomole-level analyte detection through careful tuning of SPP and LSP dispersion [

18]. In contrast, Sapkota et al. report a tenfold sensitivity increase over conventional SPR sensors in gas monitoring applications [

34].

Both approaches strategically exploit field confinement to enhance MO responses, though they do so through different optimization pathways. This contrast is reflected in the Q-factor [

66],

which captures how spectral sharpness influences sensitivity.

Nanostructured magnetoplasmonic architectures, including Au/Co/Au nanodisks and nanoporous Ag/CoFeB/Ag composites, further improve sensing performance by generating highly confined electromagnetic “hot spot” regions at plasmonic resonance. These localized fields substantially amplify the Kerr response and reduce the refractive index detection limit to the order of

RIU [

18,

132]. Such enhancements are consistent with broader advances in magnetoplasmonics, where engineered field confinement and plasmon—magnetization mode hybridization serve as key design strategies for maximizing sensitivity and tunability [

32,

117].

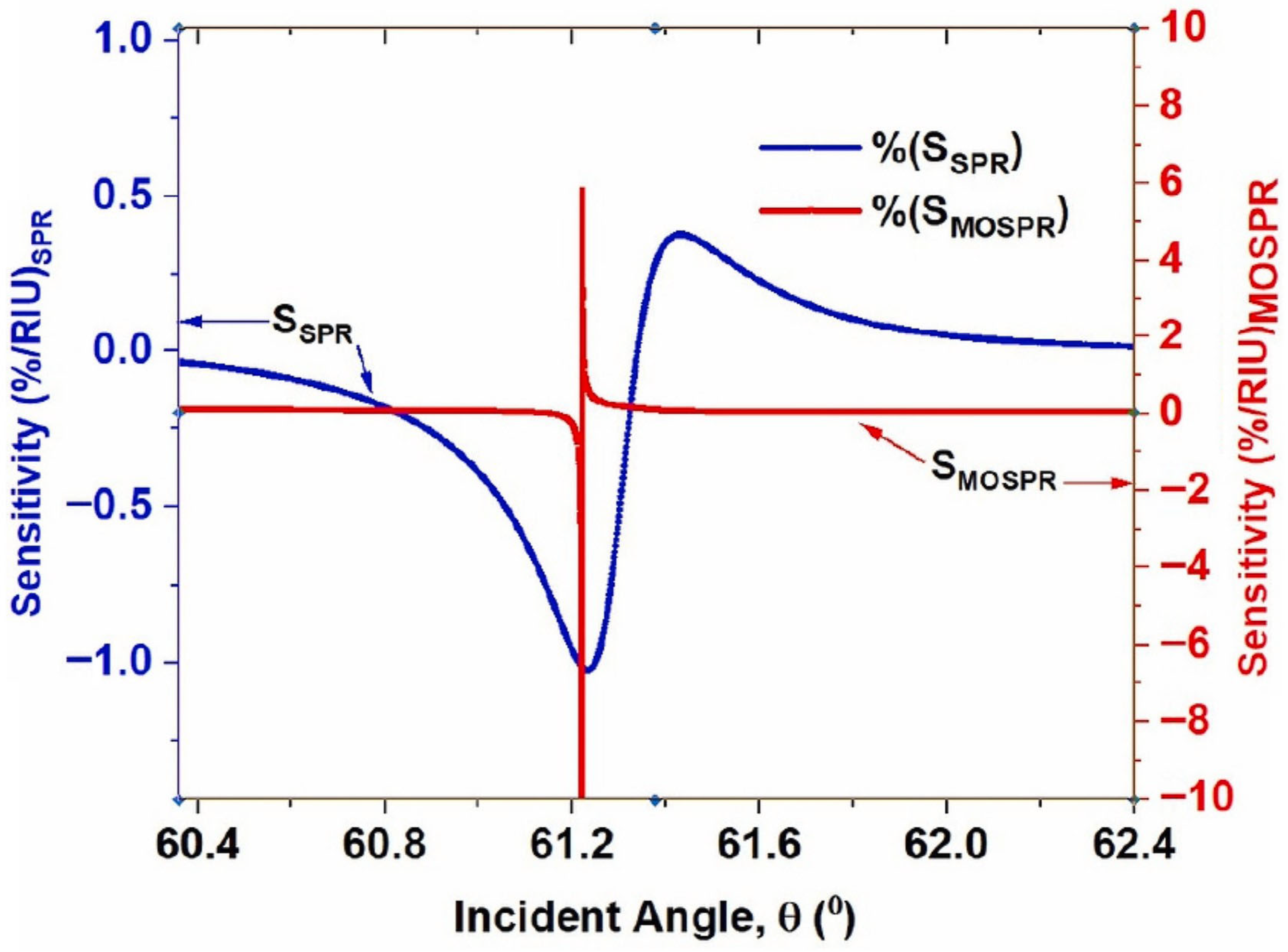

Figure 6 illustrates that MOSP provides higher refractive index sensitivity than conventional SPR through magnetic field—induced changes in reflectivity [

34,

119]. This enhanced response underpins the improved detection performance of magnetooptical sensing platforms.

7.2. Materials Landscape and Integration Readiness

The maturity of these platforms varies largely due to material constraints. Conventional ferromagnets (Co, Fe, Ni) provide a robust magnetooptical (MO) response but suffer from high damping and optical absorption, which limit resonance sharpness and stability. Ferrimagnetic garnets (e.g., YIG) offer ultra-low damping and excellent magnetooptical (MO) efficiency but require epitaxial growth, which complicates integration with plasmonic metals. Hybrid candidates such as CoFeB and emerging organic ferrimagnets (e.g., V[TCNE]x) reduce damping while retaining compatibility with planar fabrication; however, they require improved environmental stability and interface passivation for long-term operation.

Transparent conductive oxides (TCOs), including indium tin oxide (ITO) and doped copper chalcogenide nanocrystals, are gaining traction due to their tunable carrier density and capacity to support localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR)-like modes. Recent findings suggest that optimized TCO-based nanostructures can exhibit magnetoplasmonic activity exceeding that of noble metals by nearly an order of magnitude, positioning them as compelling candidates for scalable and CMOS-compatible integration.

7.3. Cross-Cutting Challenges and Scalability Needs

Despite rapid advances in magnetooptical (MO) and magnetoplasmonic platforms, several foundational challenges continue to limit scalability, device robustness, and broad technological adoption. These constraints stem from the intrinsic coupling of optical, magnetic, and electronic degrees of freedom, which requires precise control over material composition, nanoscale geometry, interfacial quality, and excitation conditions [

32,

117,

270]. In particular, many of the highest-performing structures rely on ultrathin ferromagnetic layers and plasmonic resonators with sub-wavelength feature sizes, where even small deviations in geometry or surface roughness can significantly alter resonance conditions, Kerr rotation amplitude, and overall device stability. Achieving reproducible functionality, therefore, demands fabrication techniques capable of sub-10 nm precision over large areas, which remains a persistent manufacturing bottleneck.

Furthermore, the optical and magnetic loss mechanisms in transition-metal ferromagnets introduce trade-offs that complicate optimization. Metallic ferromagnets with strong MO coefficients (e.g., Co, Fe) also exhibit high optical absorption in the visible and near-infrared regimes, reducing plasmonic quality factors and limiting field confinement. Conversely, low-loss plasmonic or dielectric media may provide minimal magnetooptical (MO) response unless carefully engineered through multilayer stacking, strain tuning, or interfacial symmetry breaking. These competing requirements become more stringent in dynamic or ultrafast applications, where spin—lattice interactions, thermal transport, and coherent spin precession must remain stable under repeated pulsed excitation.

On the system level, integration with semiconductor photonics and CMOS-compatible electronics is constrained by lattice mismatch, thermal expansion differences, and environmental degradation of magnetic layers, particularly in flexible, transparent, or wearable platforms [

6,

271,

272]. Long-term operational stability also depends on suppressing oxidation, controlling interlayer diffusion, and maintaining low surface roughness—all of which require carefully optimized encapsulation strategies that do not compromise optical performance.

Finally, the characterization and control of these systems increasingly rely on high-dimensional datasets generated by pump—probe spectroscopy, spectroscopic ellipsometry, and magnetooptical imaging. Extracting physically meaningful insights from such data requires machine learning and physics-informed modeling approaches; yet, these methods are only as reliable as the quality, diversity, and interpretability of the training data provided. Automated pattern recognition and adaptive feedback platforms offer promising solutions, but they must be implemented with rigorous physical constraints to avoid misinterpretation or overfitting.

Taken together, continued progress in MO and magnetoplasmonic technologies will require coordinated advancements in: (1) materials synthesis to reduce loss while preserving or enhancing MO response, (2) wafer-scale and flexible nanofabrication capable of producing uniform, reproducible architectures, (3) multiscale theoretical and computational frameworks that bridge quantum, electronic, and optical behavior, and (4) AI-assisted data interpretation and closed-loop experiment control to accelerate discovery and device optimization. These cross-cutting needs provide the foundation for the translational strategies and application pathways discussed in the following sections.

7.3.1. Fabrication Scalability

Achieving high-performance magnetooptical and magnetoplasmonic responses often relies on fabrication strategies that provide nanometer-scale control over layer thickness, interface quality, and pattern geometry. Techniques such as electron-beam lithography, epitaxial thin-film deposition, and high-vacuum sputtering are routinely employed to achieve this precision [

24,

160,

243]. However, these methods are inherently limited in throughput and cost, posing a significant barrier to large-area device manufacturing and commercial-scale deployment. In particular, e-beam lithography enables exceptional pattern fidelity but is intrinsically serial in nature, and epitaxial growth processes require lattice-matched substrates and stringent thermal conditions that restrict material choices and substrate size.

Translating these architectures onto flexible, CMOS-compatible, or heterogeneous device platforms remains challenging. Mechanical mismatch between magnetic layers and polymeric or oxide substrates can induce film cracking or delamination, while differential thermal expansion can degrade interfacial order during processing or device operation [

6,

271]. Additionally, environmental exposure, especially to oxygen and moisture can promote oxidation, interlayer diffusion, and surface roughening in both magnetic and plasmonic films, degrading magnetooptical (MO) contrast and long-term stability [

272]. Protective encapsulation layers can mitigate degradation but often introduce additional refractive index contrast or optical absorption that must be carefully managed.

A further challenge is the fundamental trade-off between maximizing the MO response and minimizing optical loss [

270]. Strong MO activity is often associated with transition-metal ferromagnets (e.g., Co, Fe, Ni) that exhibit high absorption in the visible and near-infrared ranges, reducing the quality factor of plasmonic and cavity resonances. Conversely, noble metals and transparent conducting oxides offer low optical loss but a comparatively weak magnetic response. Hybrid metal—dielectric and metal—oxide heterostructures, multilayer metamaterials, and epsilon-near-zero (ENZ) platforms are being actively explored to balance these competing requirements; however, their performance remains highly sensitive to nanoscale interface quality and repeatable large-area fabrication.

Addressing fabrication scalability, therefore, requires the transition from serial nanofabrication to parallel, high-throughput techniques. Nanoimprint lithography, roll-to-roll processing, and directed self-assembly show promise for pattern transfer at wafer and substrate scales but require improved control over feature uniformity, defect density, and alignment across heterogeneous layer stacks. Bridging these gaps represents a key step toward practical MO-enabled sensors, integrated photonic circuits, and reconfigurable metasurface platforms.

7.3.2. Signal Stability and Environmental Robustness

Surface oxidation, thermal fluctuations, and analyte adsorption variability can shift plasmonic resonances and reduce measurement reproducibility in MOSPR platforms [

272]. The detected MO signal scales quadratically with the magnetic moment,

making low-moment or nanoscale materials intrinsically challenging to probe [

115]. Plasmonic amplification enhances sensitivity through localized near-field enhancement as:

but is constrained by thermal heating, geometric disorder, and fabrication tolerances [

129].

7.3.3. Multiphysics Modeling and Predictive Design Complexity

Accurate device prediction requires simultaneously modeling electron interactions, magnetic ordering, and electromagnetic propagation. Many-body interactions are captured using Green’s function formalism,

While the ground-state electronic structure is determined through density functional theory,

yet both methods face scalability and accuracy limitations in disordered and strongly correlated systems [

228,

273,

274,

275,

276].

At the continuum scale, homogenization approaches,

must be validated using full-wave electromagnetic calculations,

to account for structural dispersion, near-field coupling, and nonlocal dielectric effects.

7.3.4. Phase Stability and Ultrafast Spin Dynamics

The stability of emergent magnetic phases is governed by the competition between Zeeman energy and thermal entropy.

implying that fragile spin configurations often require cryogenic stabilization. Ultrafast pump—probe techniques probe spin—lattice relaxation dynamics via

but are constrained by the time—frequency uncertainty bound,

which imposes strict requirements on laser pulse stabilization and noise suppression [

277,

278].

7.3.5. Data Complexity and AI-Driven Optimization Needs

High-resolution pump—probe spectroscopy, spectroscopic ellipsometry, and magnetooptical (MO) microscopy increasingly produce large, high-dimensional datasets that are difficult to interpret using conventional analytical workflows. Machine learning and artificial intelligence offer powerful pathways for automated feature extraction, pattern recognition, and adaptive experimental control [

37,

40]. However, the deployment of such models requires careful incorporation of physical constraints to ensure reliable performance and prevent overfitting or erroneous signal attribution.

Realizing these capabilities will depend on coordinated progress across multiple fronts, including the development of low-loss MO materials, wafer-scale and CMOS-compatible nanofabrication, multiscale computational modeling frameworks, and AI-assisted experiment design and optimization strategies [

32,

43]. Together, these advances will be essential for transitioning magnetooptical technologies from research-grade instrumentation to robust, intelligent, and application-ready platforms.

7.4. Roadmap for Technological Translation

A number of clear pathways are emerging that can accelerate the transition of magnetooptical and magnetoplasmonic systems toward application-ready platforms. First, the adoption of low-loss magnetic media and transparent-conducting-oxide (TCO) plasmonic hybrids offers a promising route to reducing damping and improving resonance quality factors; in particular, materials such as yttrium iron garnet (YIG) thin films, CoFeB alloys, and TCO-based plasmonic layers can enable a stronger magnetooptical response with minimal optical absorption. Second, progress in fabrication must shift from laboratory-scale nanopatterning toward scalable manufacturing. Techniques such as nanoimprint lithography and roll-to-roll pattern transfer are compatible with large-area flexible substrates and therefore represent viable pathways for producing deployable sensors for environmental monitoring and industrial diagnostics. Third, the integration of closed-loop sensing architectures with artificial intelligence and machine-learning—assisted spectral interpretation is expected to enhance system robustness and adaptability. Data-driven models can dynamically optimize operational set points, compensate for thermal or environmental drift, and significantly improve selectivity and molecular identification accuracy in real time [

37,

40]. Together, these strategies outline a practical roadmap toward reliable, scalable, and intelligent magnetooptical sensing platforms.

7.5. Translational Outlook

Collectively, magnetoplasmonic and magnetooptical-enhanced sensing systems are approaching a level of functional maturity that supports translation into practical applications, including gas sensing, biomedical diagnostics, and lab-on-chip photonic platforms. However, large-scale adoption will require further progress in the standardization of material stacks, scalable wafer-level fabrication, and seamless integration with CMOS-compatible optical and electronic subsystems. Notably, the growing convergence of materials science and device engineering with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML)—driven experimental automation is accelerating this transition, enabling data-guided optimization of materials, architectures, and measurement protocols. Together, these advances indicate that magnetooptical technologies are moving beyond exploratory research toward robust, deployable, and application-ready sensing platforms.