Recognizing Resilience in Children: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

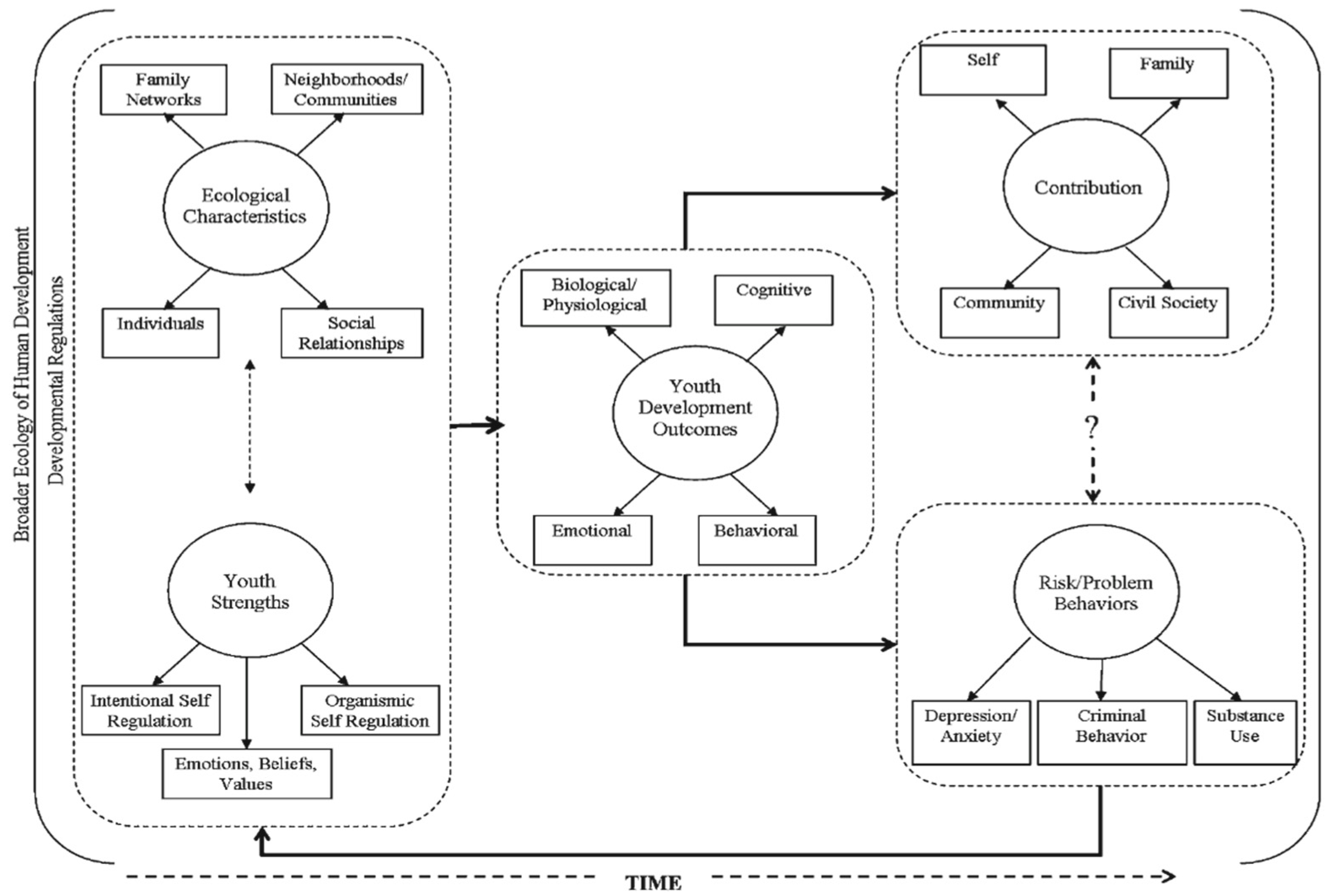

2. Conceptual Framework: Relational Developmental Systems Theory

3. Methods

4. Resilience Defined

5. Core Concepts: Sense of Belonging and Empowerment

6. Review of the Literature

6.1. The Resilience-Fostering Environment

- The single most common finding is that a child who ends up doing well had the presence of at least one stable, committed, caring, supportive adult in his life;

- The supportive context of affirming faith or cultural traditions create an atmosphere in which children are more likely to respond effectively to major stressors.

6.2. Recognizing Resilience: Individual Characteristics

6.3. The Child in Her Environment

7. General Implications for Policy and Practice

- 1

- Compassionate classrooms:

- a.

- Teacher and administrator training on topics of: stress/trauma, its developmental impact, emotional regulatory skills, respectful classrooms, growth mindset, high expectations, and establishing a sense of belonging;

- 2

- Mandatory minimum for recess and outdoor play in schools;

- 3

- Universal policy focused on building: Agency (self-efficacy), Belonging, Critical thinking (executive function), Determination, Emotional regulation, Flexibility, and Growth mindset;

- 4

- Afterschool enrichment opportunities for under resourced schools/neighborhoods;

- 5

- Access to creative art programs for all students from any SES;

- 6

- Funding for field trips for all schools;

- 7

- Safe and clean outdoor play spaces in all areas of a community;

- 8

- Mandatory healthy school meals and access to fresh food in all areas of a community;

- 9

- Parent education on the positive impact of connection and enrichment and the negative impact of stress;

- 10

- Access to consistent, high quality health care and childcare for all;

- 11

- Mentor programs to provide stable, caring adults in the lives of struggling children.

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stamper, K. (Ed.) Resilience. Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved November 2021. Volume 23. Available online: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/resilience (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Rawson, B. (Ed.) Business Resilience. TechTarget, SearchCIO. Retrieved November 2021. Volume 20. Available online: http://searchcio.techtarget.com/definition/business-resilience (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Lerner, R.M. Structure and Process in Relational, Developmental Systems Theories: A Commentary on Contemporary Changes in the Understanding of Developmental Change across the Life Span. Hum. Dev. 2011, 54, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, W.F.; Lerner, R.M. Relational-developmental-systems: Paradigm for developmental science in the postgenomic era. Brain Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Retrieved 11 December 2020. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/index.html (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Ginsberg, K.R. Building Resilience in Children and Teens: Giving Kids Roots and Wings; American Academy of Pediatrics: Elk Grove Village, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, R. What is resilience: An affiliative neuroscience approach. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, M. The social ecology of resilience. Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M.; Ghazinour, M.; Richter, J. Annual Research Review: What is resilience within the social ecology of human development? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Cutuli, J.J.; Herbers, J.E.; Reed, M.J. Resilience in Development. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology; Lopez, S.J., Snyder, C.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary Magic: Resilience Processes in Development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhamra, R.; Dani, S.; Burnard, K. Resilience: The concept, a literature review, and future directions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5375–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Moss, A.R. Child and Family Resilience: A call for integrated science, practice, and professional training. Interdiscip. J. Appl. Fam. Stud. 2015, 64, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Supportive Relationships and Active Skill-Building Strengthen the Foundations of Resilience: Working Paper No. 13. 2015. Available online: www.developingchild.harvard.edu (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Brooks, R.; Goldstein, S. Raising Resilient Children: Fostering Strength, Hope, and Optimism in Your Child; Contemporary Books: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zolkoski, S.M.; Bullock, L.M. Resilience in children and youth: A review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 2295–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 47, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Gerwirtz, A.H.; Sapienza, J.K. Resilience in Development: The Importance of Early Childhood. In Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development; Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- White, A.; Pulla, V. Strengthening the capacity for resilience in children. In Perspectives on Coping and Resilience; Pulla, V., Shatte, A., Warren, S., Eds.; Authors Press: New Delhi, India, 2013; pp. 122–151. [Google Scholar]

- Khanlou, N.; Wray, R. A Whole Community Approach toward Child and Youth Resilience Promotion: A Review of Resilience Literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2014, 12, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Annual Review: Resilience–clinical implications. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Williams, R.A. Effects of parental alcoholism, sense of belonging, and resilience on depressive symptoms: A path model. Subst. Use Misuse 2013, 48, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, B.M.; Lynch-Sauer, J.; Patusky, K.L.; Bouwsema, M.; Collier, P. Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1992, 6, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarf, D.; Saleh, M.; McGaw, K.; Hewitt, J.; Hayhurst, J.G.; Boyes, M.; Ruffman, T.; Hunter, J.A. Somewhere I belong: Long-term increases in adolescents’ resilience are predicated by perceived belonging to the in-group. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 55, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findik, L.Y. What Makes a Difference for Resilient Students in Turkey? Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2016, 62, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roffey, S. Inclusive and exclusive belonging: The impact on individual and community wellbeing. Educ. Child Psychol. 2013, 30, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, G.M.; Cohen, G.L. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science 2011, 331, 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christens, B.D.; Peterson, N.A. The role of empowerment in youth development: A study of sociopolitical control as mediator of ecological systems’ influence on developmental outcomes. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.; Munford, R.; Thimasarn-Anwar, T.; Liebenburg, L.; Ungar, M. The role of positive youth development practices in building resilience and enhancing well-being for at-risk youth. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 42, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts: A Science-Based Approach to Building a More Promising Future for Young Children and Families. 2016. Available online: http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Bowers, E.P.; Geldhof, G.J.; Schmid, K.L.; Napolitano, C.M.; Minor, K.; Lerner, J.V. Relationships with important nonparental adults and positive youth development: An examination of youth self-regulatory strengths as mediators. Res. Hum. Dev. 2012, 9, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M. Teach Your Children Well: Parenting for Authentic Success; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Flouri, E.; Midouhas, E.; Joshi, H. Family Poverty and Trajectories of Children’s Emotional and Behavioral Problems: The Moderating Roles of Self-Regulation and Verbal Cognitive Ability. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malchiodi, C. Calm, connection, and confidence: Using art therapy to enhance resilience in traumatized children. In Play Therapy Interventions to Enhance Resilience; Crenshaw, D., Ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 126–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, T.; Tandon, S.D.; O’Brennan, L.; Leaf, P.J.; Ialongo, N.S. Brief Report: Moving prevention into schools: The impact of a trauma-informed school-based intervention. J. Adolesc. 2015, 43, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.D.; Kosterman, R.; Catalano, R.F.; Hill, K.G.; Abbott, R.D. Promoting Positive Adult Functioning Through Social Development Intervention in Childhood. Arch. Pediatrics Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milteer, R.M.; Ginsburg, K.R.; Council on Communications and Media; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bond: Focus on children in poverty. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e204–e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suskind, D. Thirty Million Words: Building a Child’s Brain; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, N.M. The role of nature in children’s resilience: Cognitive and social processes. In Greening in the Red Zone: Disaster, 95 Resilience and Community Greening; Tidball, K.G., Krasny, M.E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Fenning, R.M.; Baker, J.K. Mother-child interaction and resilience in children with early developmental risk. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, W.R.; Pynoos, R.S.; Lester, P.; Layne, C.M.; Beardslee, W.R. Enhancing family resilience through family narrative co-construction. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 16, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Definition of Resilience |

|---|---|

| Masten (2001) [11] | A class of phenomena characterized by good outcomes in spite of serious threats to adaptation or development (p. 228). |

| Bhamra (2011) [12] | The capability and ability of an element to return to a stable state after a disruption (p. 5376). |

| Ungar, et al. (2013) [9] | Children’s developmental success under negative stress (p. 349). |

| Masten and Moss (2015) [13] | The capacity for adapting successfully in the context of adversity, inferred from evidence of successful adaptation following significant challenges or system disturbances (p. 6). |

| Lerner, et al. (2013) [3] | A dynamic attribute of a relationship between an individual adolescent and his/her multilevel and integrated (relational) developmental system (p. 293). |

| Harvard (2015) [14] | A positive, adaptive response in the face of significant adversity (Center on the Developing Child, p. 1). |

| Ginsberg (2011) [6] | The capacity to rise above difficult circumstances; moving forward with optimism and confidence even in the midst of adversity (p. 4). |

| Brooks and Goldstein (2001) [15] | The inner strength to cope competently and successfully with challenges, adversity, or trauma encountered daily (p. 1). |

| Zolkoski and Bullock (2012) [16] | Coping successfully with traumatic experiences, and avoiding negative paths linked with risks (p. 2296). |

| Yeager and Dweck (2012) [17] | Whether students respond positively to challenges (p. 302) |

| Masten, et al. (2013) [18] | The capacity of a dynamic system to withstand or recover from significant challenges that threaten its stability, viability, or development. |

| White and Pulla (2013) [19] | A dynamic process of interactions between a child and his/her social and physical ecology that promote adaptation and positive outcomes despite adverse situations (p. 123). |

| Khanlou and Wray (2014) [20] | (a) A process, (b) a continuum, (c) or global concept with specific dimensions (p. 68) |

| Rutter (2013) [21] | An interactive phenomenon that is inferred from findings indicating that some individuals have a relatively good outcome despite having experienced serious stresses or adversities (p. 474). |

| Lee and Williams (2013) [22] | A capacity to cope successfully with significant adversity or trauma (p. 265). |

| Masten, et al. (2009) [10] | Patterns of positive adaptation and development during or following exposure to experiences or conditions associated with negative outcomes (p. 118). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schafer, E.S. Recognizing Resilience in Children: A Review. Trauma Care 2022, 2, 469-480. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2030039

Schafer ES. Recognizing Resilience in Children: A Review. Trauma Care. 2022; 2(3):469-480. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchafer, Emily Smith. 2022. "Recognizing Resilience in Children: A Review" Trauma Care 2, no. 3: 469-480. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2030039

APA StyleSchafer, E. S. (2022). Recognizing Resilience in Children: A Review. Trauma Care, 2(3), 469-480. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2030039