The Trauma of Perinatal Loss: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scoping Review Process

2.2. Literature Search

2.3. Article Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

| Article Title | Author | Country | Year | Methodology | Population | Findings | Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Impact of Anencephaly on Parents: A Mixed-Methods Study | Berry [4] | United States | 2021 | Interpretive Phenomenology | 20 women and 4 men with a prior pregnancy complicated by anencephaly | Experiencing a pregnancy complicated by anencephaly is a traumatic experience for parents. Silence and stigma often complicate the parents’ grieving process. Parents require patient-centered care from compassionate health care professionals. Despite parents requiring additional support as they attempt to reframe their new reality following perinatal loss, only one parent received follow-up care. | “I experienced a lot of trauma. I was very disassociated. Yeah, I just got bad. I was disassociated from like everything. Like I was going through the motions, but I was in haze. I wasn’t fully present.” (p. 4) |

| From “Silent Birth” to Voices Heard: Volunteering, Meaning, and Posttraumatic Growth After Stillbirth | Cacciatore [16] | United States | 2019 | Qualitative Analysis | 191 parents who had previously experienced a stillbirth | Positive change and personal growth in the wake of trauma is an achievable outcome. Volunteerism has been found to “enhance loss accommodation”. | “We were given a beautiful blanket that was handmade to wrap and hold our son in as we said goodbye… We didn’t have many items for him. I wanted to repay the kindness that someone did for our family. Now I try to make blankets…” (p. 9) |

| Men’s Experiences of Miscarriage: A Passive Phenomenological Analysis of Online Data | Chaves [17] | United States | 2019 | Phenomenological Analysis | 31 men whose partner experienced a miscarriage | Forty-two percent of participants described their experience as “traumatic” or as having experienced “trauma”. Men often felt abandoned and isolated by both professional and social support systems. The emotional trauma of miscarriage was a long-term experience. | “I will never forget what I saw… It’s burned into my mind forever” (p. 670) |

| Stillbirth, Still Life: A Qualitative Patient-Led Study on Parents’ Unsilenced Stories of Stillbirth | Gillis [5] | Canada | 2020 | Qualitative | 8 women and 3 men who had experienced stillbirth within the past 5 years | Parents desired to honor the birth and death of their neonate, yet were rarely afforded the opportunity to do so. The social pressure to remain silent about stillbirth experiences negatively impacted parents. | “Parents felt that specialized care should extend beyond the acute trauma and perceived a lack of care continuity. Parents described a feeling of being pelted with leaflets and bombarded by counsellors early on, which was unfitting for their acute state of trauma, and how this attention was later abandoned when they could have used it” (p. 128) |

| Perinatal Grief and Related Factors After Termination of Pregnancy for Fetal Anomaly: One Year Follow-up Study | GÜÇLÜ [18] | Turkey | 2021 | Quantitative | 46 women who underwent termination for fetal anomaly | Termination for fetal anomaly is a traumatic event, yet most countries have no organized process for offering professional mental health to this patient population. Providing professional interventions and follow-up may help women to better assimilate to life after loss. | “Determining and treating the mental problems that may be caused by a perinatal loss is important for the maternal health. Most of the countries still have no organized proposal for professional help for these women and there is no evidence-based guide to help them with that process.” (p. 226) |

| New Understandings of Fathers’ Experiences of Grief and Loss Following Stillbirth and Neonatal Death: A Scoping Review | Jones [19] | United Kingdom | 2019 | Scoping Review | 27 articles focusing on fathers’ experiences with perinatal loss | The social pressures of fathers to appear strong and support their grieving partner often masked men’s grief and symptoms of PTSD. Multiple studies included in this review document symptoms of PTSD in fathers following perinatal loss. | “Measures used to assess PTSD symptoms may fail to fully capture paternal experiences of grief. Lastly, fathers may be expected to be strong and support the mother which may result in the underreporting of symptoms or the seeking of professional support” (p. 4) |

| Grief, Traumatic Stress, and Posttraumatic Growth in Women Who Have Experienced Pregnancy Loss | Krosch [20] | Australia | 2016 | Quantitative | 328 women who had previously experienced miscarriage | Miscarriage is often a traumatic event which disrupts parents’ core beliefs. Posttraumatic stress disorder was prevalent among participants. | “Reported levels of posttraumatic stress were considerably higher considering that the mean time since loss was just over 4 years. By this time, posttraumatic stress symptoms would typically be expected to have decreased considerably” (p. 429) |

| When Death Precedes Birth: The Embodied Experiences of Women with a History of Miscarriage or Stillbirth—A Phenomenological Study Using Artistic Inquiry | Kurz [21] | United States | 2020 | Phenomenological | 3 women with a history of miscarriage | Miscarriage causes a developmental disruption in a woman’s life. Many women who experience miscarriage become “stuck” and do not know how to move on following their loss. Grief is embodied, potentially for years. | “The emerging universal theme stuck in emptiness expresses the death being experienced in and towards the participants’ body. Experiencing a state of being “stuck and frozen” and “paralyzed” contributed to feeling “like there’s no reason to hurry or even be slow” and “you just can’t move.” The inability to move was related to their embodied experiences of emptiness.” (p. 207) |

| “Ghosts” in the Womb: A Mentalizing Approach to Understanding and Treating Prenatal Attachment Disturbances During Pregnancies After Loss | Markin [22] | United States | 2018 | Psychotherapeutic Discussion | 92 parents who had previously experienced perinatal loss | Forty percent of participants experienced posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder. | “For many participants, the non-trauma focused counselling did not ‘touch’ their traumatic experiences of perinatal bereavement, which were described by one participant as ‘trying to heat up the North Sea with a hot water bottle’.” (p. 4) |

| ICD-11 Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) in Parents with Perinatal Bereavement: Implications for Treatment and Care | Martin [23] | United Kingdom | 2020 | Mixed-Methods | 74 women with a history of perinatal loss within the past 5 years | Forty percent of participants met criteria for traumatic stress and 39% experienced PTSD, yet there is no direct strategy for routinely detecting and treating PTSD following perinatal loss. | “All participants interviewed supported that flexible therapies require to be developed to alleviate complex trauma symptoms.” (p. 6) “Clearly and in relation to any additional complexities that may coexist with a diagnosis of PTSD, which represent as CPTSD, there are wider unmet needs, which may include for example PND, complicated grief, and/or anxiety disorder” (p. 6) |

| Psychological Consequences of Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death in a Sample of Bereaved Parents | Murphy [24] | Ireland | 2014 | Quantitative—Survey | 455 (253 women, 191 men) participants who experienced perinatal loss between 18 weeks gestation and birth within the past 5 years | Parents who experienced perinatal loss were susceptible to symptoms of PTSD up to five years following the loss, including interpersonal sensitivity and aggression. | “Bereaved parents had elevated levels of trauma-specific and psychological outcomes following the loss of an infant. However, when examining differences between the type of loss, there were no significant differences found on any of the TSC subscales.” (p. 65) |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder After Subsequent Birth to a Gestational Loss: An Observational Study | Ordonez [25] | Spain | 2020 | Observational Mixed-Methods | 115 women who had suffered previous gestational losses | Twenty-two percent of participants experienced PTSD. Type of loss, gestational age (including voluntary and involuntary termination of pregnancy), and educational level were not predictors of PTSD following perinatal loss. Subsequent pregnancies acted as a stressor and increased the risk of PTSD, particularly following multiple gestational losses. | “PTSD continues to be poorly recognized after a perinatal loss and, consequently, its symptoms are treated as symptoms of grief. This is problematic since these two entities do not share the same protective factors or the same risk factors, and they do not in parallel.” (p. 134) “Erroneously, professionals may consider that the effects of a gestational loss are resolved after a pregnancy that ends successfully; however, the symptoms can be reactivated and endure, affecting the health of the mother and the child.” (p. 134) |

| Mothers’ Perspectives on the Perinatal Loss of a Co-Twin: A Qualitative Study | Richards [26] | United Kingdom | 2015 | Qualitative | 14 women who experienced the loss of a co-twin | Gestational loss in a twin pregnancy introduced a new layer of complexity for women. Women placed their grief on hold to care for the surviving twin. Study participants felt the trauma of their experience influenced their perspective and interactions with the surviving twin. Though bereavement resources were offered in the care setting, women were not ready for support. Repeated offers for bereavement resources did not occur post-discharge. Consequently, when symptoms of trauma arose, the women did not have professional support. | “Mothers also talked of the need to keep their emotions ‘on hold’, whilst caring for the surviving baby. As a result, a strong grief reaction often emerged weeks, months or even years after their babies were discharged from hospital” (p. 4) |

| Parents’ Experiences of Care Following the Loss of a Baby at the Margins Between Miscarriage, Stillbirth and Neonatal Death: A UK Qualitative Study | Smith [27] | United Kingdom | 2020 | Qualitative Interview | 38 (28 women, 10 men) parents experiencing perinatal loss at 20–23 weeks gestation | The way women are treated during miscarriage and stillbirth impacts the grief direction and trajectory. Words played a significant role in the trauma of perinatal loss. Health care professionals play an important role in decreasing the overall trauma of the perinatal loss experience. | “Our findings reinforce the need to use language in healthcare encounters that validates the loss of a baby, acknowledges the hopes and dreams associated with that loss, and prepares parents for the experience of labour and birth” (p. 873) |

| Depression, Anxiety, PTSD, and OCD After Stillbirth: A Systematic Review | Westby [13] | Norway | 2021 | Systematic Review | 13 qualitative articles discussing anxiety, depression, and PTSD following stillbirth | Women who experience stillbirth have an increased risk for developing PTSD following the loss when compared to women with healthy, live births. | “To conclude, the present review finds that parents who experience SB display a considerably higher risk of experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD compared to parents with live births.” (p. 15) |

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Content Categories

3.2.1. Prevalence of Trauma

3.2.2. Characteristics of Trauma

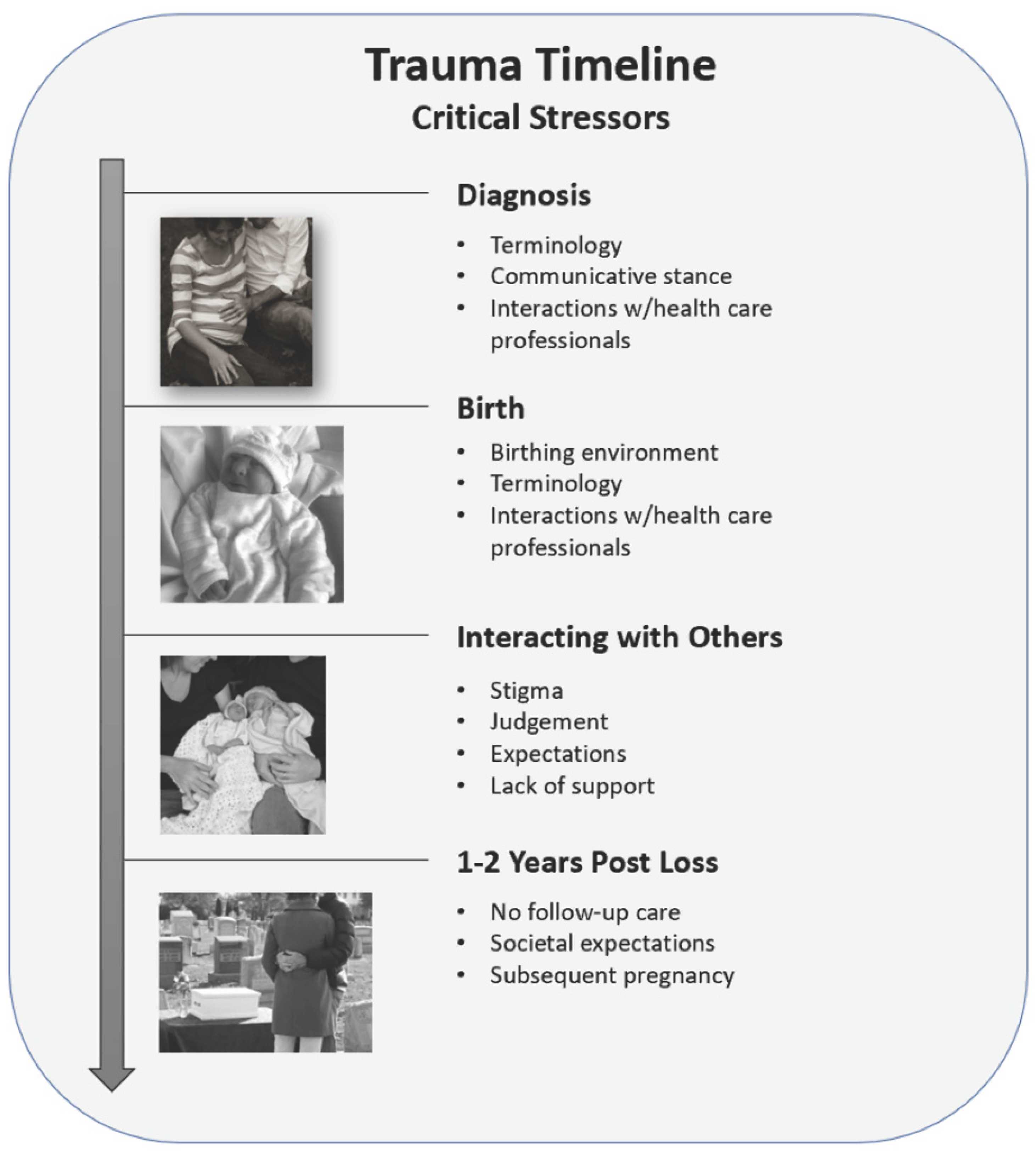

3.2.3. Key Milestones

Trauma of the Diagnosis

Trauma of the Delivery and Birth

Trauma of Interacting with Others

Trauma following the Loss Experience

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Future Research

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Newborns: Improving Survival and Well-Being. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborns-reducing-mortality (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Ely, D.M.; Driscoll, A.K. National vital statistics reports infant mortality in the United States, 2018: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2020, 69, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, S.N.; Marko, T.; Oneal, G. Qualitative Interpretive Metasynthesis of Parents’ Experiences of Perinatal Loss. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 50, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.N.; Severtsen, B.; Davis, A.; Nelson, L.; Hutti, M.H.; Oneal, G. The impact of anencephaly on parents: A mixed-methods study. Death Stud. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillis, C.; Wheatley, V.; Jones, A.; Roland, B.; Gill, M.; Marlett, N.; Shklarov, S. Stillbirth, still life: A qualitative patient-led study on parents’ unsilenced stories of stillbirth. Bereave. Care 2020, 39, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, C. National Standards for Bereavement Care Following Pregnancy Loss and Perinatal Death; HSE National Standards for Bereavement Care: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ordoñez, E.; González-Cano-Caballero, M.; Guerra-Marmolejo, C.; Fernández-Fernández, E.; García-Gámez, M. Perinatal Grief and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Pregnancy after Perinatal Loss: A Longitudinal Study Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sola, C.; Camacho-Ávila, M.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Jiménez-López, F.R.; Hernández-Sánchez, E.; Conesa-Ferrer, M.B.; Granero-Molina, J. Impact of Perinatal Death on the Social and Family Context of the Parents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutti, M.H.; Myers, J.; Hall, L.A.; Polivka, B.J.; White, S.; Hill, J.; Kloenne, E.; Hayden, J.; Grisanti, M.M. Predicting grief intensity after recent perinatal loss. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017, 101, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enez, O. Complicated grief: Epidemiology, clinical features, assessment, and diagnosis. Curr. Approaches Psychiatry 2018, 10, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kartha, A.; Brower, V.; Saitz, R.; Samet, J.; Keane, T.; Liebschutz, J. The Impact of Trauma Exposure and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder on Healthcare Utilization Among Primary Care Patients. Med Care 2008, 46, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elisseou, S.; Puranam, S.; Nandi, M. A Novel, Trauma-Informed Physical Examination Curriculum for First-Year Medical Students. J. Teach. Learn. Resour. 2019, 15, 10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westby, C.L.; Erlandsen, A.R.; Nilsen, S.A.; Visted, E.; Thimm, J.C. Depression, anxiety, PTSD, and OCD after stillbirth: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Represent. Interv. 2012, 69, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cacciatore, J.; Blood, C.; Kurker, S. From “Silent Birth” to Voices Heard: Volunteering, Meaning, and Posttraumatic Growth After Stillbirth. Illn. Crisis Loss 2017, 26, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, M.S.; Handley, V.; Jones, R.L.; Eddy, B.; Poll, V. Men’s Experiences of Miscarriage: A Passive Phenomenological Analysis of Online Data. J. Loss Trauma 2019, 24, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guclu, O.; Senormanci, G.; Tuten, A.; Gok, K.; Senormanci, O. Perinatal Grief and Related Factors After Termination of Pregnancy for Fetal Anomaly: One-Year Follow-up Study. Arch. Neuropsychiatry 2021, 58, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.; Robb, M.; Murphy, S.; Davies, A. New understandings of fathers’ experiences of grief and loss following stillbirth and neonatal death: A scoping review. Midwifery 2019, 79, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosch, D.J.; Shakespeare-Finch, J. Grief, traumatic stress, and posttraumatic growth in women who have experienced pregnancy loss. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2017, 9, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurz, M.R. When Death Precedes Birth: The Embodied Experiences of Women with a History of Miscarriage or Stillbirth—A Phenomenological Study Using Artistic Inquiry. Am. J. Dance Ther. 2020, 42, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markin, R.D. “Ghosts” in the womb: A mentalizing approach to understanding and treating prenatal attachment disturbances during pregnancies after loss. Psychotherapy. 2018, 55, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J.H.; Patterson, J.; Paterson, C.; Welsh, N.; Dougall, N.; Karatzias, T.; Williams, B. ICD-11 complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) in parents with perinatal bereavement: Implications for treatment and care. Midwifery 2021, 96, 102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.; Shevlin, M.; Elklit, A. Psychological Consequences of Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death in a Sample of Bereaved Parents. J. Loss Trauma 2013, 19, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, E.F.; Díaz, C.R.; Gil, I.M.M.; Manzanares, M.T.L. Post-traumatic stress disorder after subsequent birth to a gestational loss: An observational study. Salud Ment. 2020, 43, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Graham, R.; Embleton, N.D.; Campbell, C.; Rankin, J. Mothers’ perspectives on the perinatal loss of a co-twin: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, L.K.; Dickens, J.; Atik, R.B.; Bevan, C.; Fisher, J.; Hinton, L. Parents’ experiences of care following the loss of a baby at the margins between miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death: A UK qualitative study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 127, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ironside, P.M. New Pedagogies for Teaching Thinking: The Lived Experiences of Students and Teachers Enacting Narrative Pedagogy. J. Nurs. Educ. 2003, 42, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denney-Koelsch, E.; Cote-Arsenault, D. Life-limiting fetal conditions and pregnancy continuation: Parental decision-making processes. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleis, A.I.; Sawyer, L.M.; Im, E.-O.; Messias, D.K.H.; Schumacher, K. Experiencing Transitions: An Emerging Middle-Range Theory. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2000, 23, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berry, S.N. The Trauma of Perinatal Loss: A Scoping Review. Trauma Care 2022, 2, 392-407. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2030032

Berry SN. The Trauma of Perinatal Loss: A Scoping Review. Trauma Care. 2022; 2(3):392-407. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2030032

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerry, Shandeigh N. 2022. "The Trauma of Perinatal Loss: A Scoping Review" Trauma Care 2, no. 3: 392-407. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2030032

APA StyleBerry, S. N. (2022). The Trauma of Perinatal Loss: A Scoping Review. Trauma Care, 2(3), 392-407. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2030032